The Cherokee Commission, was a three-person bi-partisan body created by President Benjamin Harrison to operate under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, as empowered by Section 14 of the Indian Appropriations Act of March 2, 1889. Section 15 of the same Act empowered the President to open land for settlement. The Commission's purpose was to legally acquire land occupied by the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in the Oklahoma Territory for non-indigenous homestead acreage.

Eleven agreements involving nineteen tribes were signed over during the period of May 1890 through November 1892. The tribes resisted cession. Not all understood the terms of the agreements. The Commission tried to dissuade tribes from retaining the services of attorneys. Not all interpreters were literate. Agreement terms varied by tribe. As negotiations with the Cherokee Nation snagged, the United States House Committee on Territories recommended bypassing negotiations and annexing the Cherokee Outlet.

The Commission continued to function until August 1893. Lawsuits, Supreme Court rulings, investigations and mandated compensation for irregularities ensued through the end of the 20th Century. Congress failed to respond to a legal protest from the Tonkawa, or to an Indian Rights Association investigation that condemned the Commission's actions with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Commission attempts to negotiate signed agreements produced no results with the Osage, Kaw, Otoe and Ponca.

The 1887 Dawes Act[1] empowered the President of the United States to survey commonly held tribal lands and allot the land to individual tribal members, with the individual land patents to be held in trust as non-taxable by the government for 25 years.

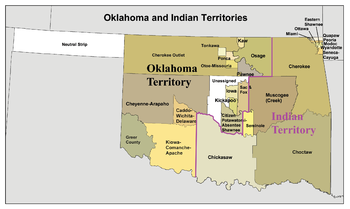

On March 2, 1889, President Grover Cleveland signed the Indian Appropriations Act into law. Section 14 of the Act authorized the President to appoint a three-person bi-partisan commission to negotiate with the Cherokee and other tribes in Indian Territory for cession of their lands to the United States. Benjamin Harrison became President on March 4.[2][3] The body was officially named the Cherokee Commission, and its existence ended in August 1893.[4][5][6] Section 15 of the same Act empowered the President to open land for settlement.[2] On May 2, 1890, President Harrison signed into law the Oklahoma Organic Act creating the Oklahoma Territory.[7][8][9]

On July 1, 1889, the Commission received its initial funding. Food, transportation and lodging were all compensated, plus $5 per diem. The commissioners received an additional $10 per diem while they were actually in service.[10] Congress appropriated an additional $20,000 for the Commission to continue its work.[11] In 1892, Congress appropriated another $15,000 for the Commission.[12] March 1893, Commission got $15,000 additional appropriation.[13]

The Cherokee Commission was to operate under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, John Willock Noble, and his successor, Michael Hoke Smith. Noble's directive to the Commission was to offer $1.25 per acre, but to adjust that amount if the situation favored it.[10] Lucius Fairchild of Wisconsin was appointed the first Chairman of the Commission.[14] Fairchild submitted his resignation to President Harrison after the committee's first endeavor failed in negotiations with the Cherokee.[15][16] Angus Cameron of Wisconsin was appointed to replace Fairchild as Chairman of the Commission, and resigned after three weeks. David H. Jerome of Michigan was appointed to fill the chairman vacancy.[17] The lone Democrat on the Commission was Judge Alfred M. Wilson of Arkansas.[18] John F. Hartranft, recipient of the Medal of Honor[19] and former Governor of Pennsylvania, became the initial third person on the committee.[14] Hartranft died on October 17, 1889.[20] President Harrison appointed his friend Warren G. Sayre of Indiana to replace Hartranft.[21]

The Iowa tribe is believed to have originated in Wisconsin. To avoid white settlers on their lands, the tribe moved to Iowa and Missouri, but later ceded their land and relocated to the Kansas-Nebraska border. In 1878, the full-bloods of the tribe moved to Indian Territory.[22]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Iowa reservation population was counted at 102.[23] Reservation acreage was reported as 225,000 acres (910 km2; 352 sq mi), west of the Sac and Fox reservation with comparable land. The population had members who were conversant in the English language, and some wore what was termed "citizens' clothes". Income was estimated at $50 per capita annually.[24]

Lucius Fairchild and the Commission approached the Iowa on October 18, 1889, and were rebuffed.[25] In May 1890, the Commission under David H. Jerome returned for negotiations, notifying the tribe of an October cessation to cattle grazing leases. Jerome told them the President was offering individual homesteads, and offering to take the resulting surplus land off their hands. Chief William Tohee stood firm that the Iowa preferred to keep their entire reservation for future generations. Jerome warned that failure to acquiesce would force the government to employ the Dawes Act. The Iowa felt that allotment and money was not good for the tribe, and they were still awaiting past government monies owed them. Many Iowa expressed concern about their children's forced assimilation in white schools, and were distrusting of the government. The Commission reiterated the threat of forced Congressional allotments. Jefferson White Cloud announced that the Iowa would sign the agreement.[26]

On May 20, 1890, at the Iowa Village on their reservation, the tribe signed the Agreement with the Iowa (1890) to cede all their land, in return for $60,000 (less than 27 cents per acre) divided per capita and paid in five installments, spread out over a 25-year period. The allotment was 80 acres (0.32 km2; 0.13 sq mi) per person. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 60 days of government agents initiating the process. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the special agent. Article IX of the agreement addressed the frail situation with Chief William Tohee and his wife Maggie. Due to his blindness and advanced age, the childless couple were to be paid $350 for their care and well-being. Tribal member Kirwan Murray acted as interpreter. Congress ratified the agreement on February 13, 1891.[27]

In 1929, the United States Court of Claims rendered a judgment that the tribe had been underpaid, due to irregularities. The tribe was awarded $254,632,59.[28]

The Sac and Fox Nation in Oklahoma. also called Sauk and Fox, were moved to Indian Territory as a result of Article 6, in the Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes (1867).[29] In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Sac and Fox reservation population was counted at 515. Reservation acreage was reported as 479,667 acres (1,941.14 km2; 749.480 sq mi), juxtaposed between the Cimarron, North Fork and Canadian rivers. It was in use as grazing, farming and orchards.[23] Living conditions were reported as tipis or bark houses, with their main clothing being blankets. The Fox and Sac National Council was credited with uplifting the morality of the tribe by prohibiting polygamy, and requiring lawful marriages.[24]

The Commission under Lucius Fairchild first met Moses Keokuk and the Sac and Fox in October 1889. Fairchild offered the tribe its choice of land for the allotments, and $1.25 per acre for surplus land.[30] When Jerome assumed the Chairmanship, the Commission returned for negotiations on May 28, 1890. Principal chief Maskosatoe was in attendance, but Keokuk, who spoke no English, led the tribal negotiations through an interpreter. Keokuk inquired about the allotment acreage and how much land the Commission wanted them to cede. Jerome cited the Dawes Act allotment directive of 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) to heads of household, 80 acres (0.32 km2; 0.13 sq mi) for single persons over 18 years of age, and 40 acres (0.16 km2; 0.063 sq mi) for persons under 18 years of age. Keokuk countered with 200 acres (0.81 km2; 0.31 sq mi) per person and a cession at $2.00 per acre. Jerome balked at the suggestion. Keokuk and the Sac and Fox National Council forced the Commission to agree to 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) per person, regardless of age or marital status. The twist was that the Commission required land patents for only half the per person acreage to be held in trust for 25 years, with the other half held in trust for only 5 years. The deal would allow tribal members to sell half their acreage after 5 years.[31]

At the seat of government of the Sac and Fox Nation, the tribe signed the Agreement with the Sauk and Fox (1890) on June 12, 1890 to cede their land in return for $485,000 (slightly over $1 per acre). $300,000 of the total payment was to be placed in the United States Treasury, $5,000 to be paid to the local Indian agent to be expended under the direction of the National Council of the Sac and Fox, and the remaining $180,000 to be paid per capita within three months of Congressional ratification of the agreement. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within four months of allotting agents arriving to begin the process. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent. The number of allotments was limited to 528, and any allotment over that limit would result in $200 per excess allotment being deducted from the $485,000. Congress ratified the agreement on February 13, 1891.[32]

In 1964, in response to an appeal of the tribal claim, the United States Court of Claims ruled the tribe had been underpaid, and awarded them $692, 564.14.[33]

The Citizen Band of Potawatomi were so named because of the Treaty with the Potawatomi (1887), which promised the band full citizenship in exchange for their agreement to move to a reservation.[34] In 1872, the United States Congress authorized the Potawatomi reservation to be in Indian Territory.[35]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Citizen Band of Potawatomi reservation population was counted at 480.[23] The reservation was reported at 575,000 acres (2,330 km2; 898 sq mi), most of it between Little River and the South Canadian.[24] The band were reported as having white blood, almost all conversant in both written and spoken knowledge of the English language. They were reported as a wealthy populace. Allotments assigned by N.S. Porter had been happening for two years.[36]

On June 25, 1890, at Shawneetown, the tribe signed the Agreement with the Citizen Band of Potawatomi (1890) and ceded their 575,870.42 acres (2,330.4649 km2; 899.79753 sq mi) for $160,000 (slightly less than 28 cents per acre) . An attorney had been engaged for the tribe during the negotiations.[37] Many Potawatomi allotments had already been done in accordance with the Dawes Act. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Those allotments, added to additional allotments were limited to a total of 1,400. The agreement stated that if additional allotments were needed, that $1 for each acre of land needed was to be deducted from the $160,000 paid the tribe, and divided per capita, for its land cession. After February 8, 1891, right to allotment ceased. Tribal member Joseph Moose acted as interpreter. Congress ratified the agreement on March 3, 1891.[38]

In 1968, the Indian Claims Commission awarded the Potawatomi $797,508.99, as part of its ruling that the land sold in 1890 had actually been worth $3 an acre.[39]

The Treaty with the Shawnee (1825) provided for a reservation in Kansas.[40] The Shawnee who were living on the Oklahoma Potawatomi reservation were given the name Absentee-Shawnee, because they were absent from the Shawnee reservation in Kansas.[41]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Absentee-Shawnee population was counted at 640.[23] Their acreage was reported as being part of the Potawatomi reservation, on fertile ground between the North Fork and Canadian rivers. They were reported as having advanced to what was considered civilized clothing, living in log houses, and owning livestock. Populace was split between two bands. The Lower Shawnee under Chief White Turkey and the Upper Shawnee under Big Jim. Allotments assigned by N.S. Porter had been happening for two years.[36]

On June 26, 1890, at Shawneetown, The Absentee-Shawnee signed the Agreement with the Absentee Shawnee (1890) and ceded 578,870.42 acres (2,342.6055 km2; 904.48503 sq mi) for $65,000 (less than 11 cents an acre).[37] Big Jim of the Upper Shawnee refused to sign the agreement.[39] The Shawnee allotments were done in accordance with the Dawes Act, and limited to 650 allotments, including the allotments made prior to the agreement. If additional allotments over 650 were made, $1 for each acre of land therein was to be deducted from the $65,000 paid the tribe. Tribal members had until January 1, 1891 to select their allotments. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent by February 8, 1891. After that date, right to allotment ceased. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Tribal member Thomas W. Alford acted as interpreter. Congress ratified the agreement on March 3, 1891.[42]

In 1999, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that only the Potawatomi had proprietary rights to the reservation land ceded in 1890, so the Absentee-Shawnee were unable to share in the 1968 award for under payment.[43]

The 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie set the Cheyenne and Arapaho boundaries as between the North Platte and the Arkansas rivers in Colorado. The 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise ceded most of the tribal land from the 1851 treaty.[44] In the 1865 Treaty of Little Arkansas, the tribes were removed to the southern boundary of Kansas.[45] The Treaty of Medicine Lodge, signed by the southern Arapaho and Cheyenne on October 28, 1867, assigned the two tribes to live on the same reservation within the Cherokee Outlet, and also stipulated that any land cession required the signature of three-fourths of all the adult males of the reservation population.[46][47]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Charles F. Ashley, the total reservation population was Cheyenne 2, 272 and Arapaho 1,100. There had been much trouble with the Dog Soldiers preventing rations being issued to those who allowed their children to be enrolled in school.[48]

The Ghost Dance religion, as practiced by a Northern Paiute named Wovoka made its influence felt among the Arapaho at this time. Wovoka was the son of a prophet named Tavibo, and according to historian James Mooney, was considered "The Messiah" of the Ghost Dance.[49] The Cheyenne first learned about this Messiah in 1889. He was alleged to live near the Shoshone in Wyoming and would bring back the buffalo and remove the white people from tribal land. A delegation led by Porcupine was sent to observe the Ghost Dance. In his account upon their return, Porcupine had become a full believer in both the Messiah and the dance. When questioned by the military authority, Porcupine gave a total accounting, but Mooney notes that in his enthusiasm, Porcupine might have embellished a bit.[50] Some abandoned their work in favor of the dancing. Agent Ashley tried to put a halt to it.[51]

On July 5, 1890, the Commission held a preliminary meeting with Old Crow, Whirlwind and Little Medicine, all opposed to cession. Jerome received instructions from Noble to follow the Treaty of Medicine Lodge directive in getting three-fourths of adult males to sign the agreement. On July 7, the Commission opened negotiations with the 1887 Dawes Act, which empowered the President to make allotments. The tribes refused to negotiate, citing their land as having been given to them by the Great Spirit and by the terms of the Treaty of Medicine Lodge. At the July 9 meeting, Sayre presented the Commission's proposal and told the tribes they, "...will be the richest people on earth." The crowd balked.[52] On July 14, Jerome threatened the government's right to cut off rations. The Cheyenne began boycotting the sessions on July 15. Both Jerome and Sayre threatened them with the Dawes Act.[53] On July 21, the Arapaho Army scouts walked out of the negotiations.[54]

Jerome, Sayre and Noble met in New York to agree on requests for the President: 1) Amend the Dawes Act to implement a time limit for acceptance; 2) Forbid outside cattle on the land; and 3) Cancel the attorney contracts if the attorneys were influencing the tribal resistance.[55] Noble learned that Cheyenne chiefs Whirlwind, Old Crow, Little Medicine, Howling Wolf and Little Big Jake were in disagreement with the Commission over the attorney contract. On October 7, the Cheyennes boycotted the negotiations, and the Arapaho refused to continue.[56]

Collecting of signatures began in Darlington, on October 13. By November 12, Noble declared sufficient signatures for the Agreement with the Cheyenne and Arapaho (1890). Tribal members complained of fraud, citing signatures of women and underage males counted. It was also alleged that rather than counting the number of signatures separately by tribe, the Commission had used the aggregate total halved.[57] Under the terms of the agreement signed October 1890, the tribes were to receive $1,500,000. Two payments were to be $250,000 each, and the remaining $1,000,000 to be retained by the Treasury of the United States at five percent interest. Allotments of 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) per person were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 90 days of Congressional ratification of the agreement. Failed to make the selection within the time frame, would cede selection for them to the local agent. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Congress ratified the agreement on March 3, 1891.[58]

Former Indian agents John D. Miles and D.B. Dwyer, Secretary Noble's law firm associate M.J. Reynolds, and former Kansas Governor Samuel J. Crawford were contracted by the tribes, and approved by Secretary Noble, to represent the Cheyenne and Arapaho.[59] Their original fees were 10% of the cession agreement, deducted from the second cash installment paid to the tribes.[60] Jerome questioned the wisdom of having attorneys whom the tribes distrusted as acting solely in the government's interest. Noble and the attorneys revised their contracts to adjust the 10% commission to a sliding scale.[56] When the tribes refused to deal with contracted attorneys, the team of lawyers mainly assisted with the gathering of signatures to approve the contract.[61] The government deducted $67,000 for attorneys fees from the 1892 second installment payment to the Cheyenne and Arapaho.[62]

The deduction for attorney fees, led the tribes to address the grievance to the government. Among their supporters were John H. Seger, former Indian agent Captain J.M. Lee, and Charles Painter of the Indian Rights Association. Painter's investigative findings were published by the Indian Rights Association in 1893 as Cheyennes and Araphos Revisited and a Statement of Their Contract with Attorneys. Therein, Captain Lee accused the contractual arrangement as being "...misrepresentation, fraud and bribery." Painter also accused the attorneys of bribery, and of causing the tribes to lose three-fourths of the value of their land. As a result of the investigation, Congress did nothing. In 1951, the tribes brought suit against the United States, through the Indian Claims Commission. The findings were that the 51,210,000 acres (207,200 km2; 80,020 sq mi) involved were worth $23,500,000 at the time of the agreement. The tribes reached a settlement with the government in the amount of $15,000,000.[62][63]

Article 9 of the Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw (1855) provided for the United States to lease the area between the 98th and 100th Meridians and the South Canadian River and Red River, for the purpose of permanent settlement of the Wichita and other tribes, and became officially titled the Leased District.[64][65] After the Civil War, Article 3 of the Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw (1866) ceded the Leased District to the United States for the sum of $300,000.[66][67] In 1867, the Kiowa and Comanche received reservations in the district. In 1868, the Wichita and Caddo received district reservations. The Cheyenne and Arapaho received district reservations in 1869.[68][69] Because the Wichita felt threatened by having these other tribes so near to them, in 1872 the government negotiated an agreement with the Wichita to increase their own reservation to 743,610 acres (3,009.3 km2; 1,161.89 sq mi). The agreement was never ratified by Congress, and the Wichita claim to the acreage would become a point of legal dispute with the Choctaw and Chickasaw upon the signing of the Commission agreement with the Wichita.[70][71]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Charles E. Adams, the total Wichita reservation population of 991 was divided into six bands: 174 Wichitas, 538 Caddo, 150 Tawakoni, 66 Kichai, 95 Delaware and 34 Waco.[72]

The Commission opened negotiations with the Wichita on May 9, 1891, by presenting the dictates of the Dawes Act, and asking the Wichita to commit to cession. David Jerome was immediately challenged by Tawakoni Jim, who argued for an attorney to represent the tribes. Jerome tried to dissuade the idea as a waste of money and time. Tawakoni Jim also challenged the acreage being offered under allotments. Caddo Jake stated that the priority should be educating the children before any negotiations could take place.[73] Comments from tribal members reflected on the distrust of the government's word, based on broken treaty promises of the past. Caddo Jake made reference to the indigenous people's experience with Christopher Columbus, which provoked a retort from Jerome that Christopher Columbus had never been on the North American continent. Caddo Jake would also draw the parallel between the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and the American tribes. Sayre presented a Commission proposal that was the standard 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) allotment, and a payment of $286,000 for surplus land. The crowd pressed for the price per acre, and Sayre finally conceded they were offering the Wichita only 50 cents per acre. When it became evident that the Wichita would not negotiate without an attorney, the government produced Luther H. Pike to represent them.who had persuaded [74] Eventually, Pike and the Wichita agreed to the Commission's terms, with the exception of the price per acre. Jerome agreed to allow Congress to set the price.[75]

On June 4, 1891 at Anadarko, the Agreement with the Wichita and Affiliated Bands (1891) ceded their surplus land, with Congress setting the price per acre. Allotments were 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi), and limited to a total 1,060 allotments. Each allotments in excess of that amount was to reduce the total amount Congress approved for payment of the surplus land. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 90 days of Congressional ratification of the agreement. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent. Land patents to the individual land allotted were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Interpreters Cora West and Robert M. Dunlap attested to having fully interpreted the terms of the agreement to the tribes before signing began. Congress ratified the agreement March 2, 1895.[76]

In 1899, the Court of Claims rendered a judgment, that only the Choctaw and Chicksaw were entitled to the payment for the surplus land. The Wichita appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which overturned the ruling. The Court of Claims awarded the Wichitas $673.371.91 ($1.25 an acre) for their surplus land. When Congress finally appropriated the funding in 1902, it deducted 43,332.93 from the total payment for attorney fees.[77]

The nomadic Kickapoo were first known to inhabit Michigan, and by the 19th Century were split between Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. The Texas band migrated to Mexico.[78] In 1873, Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, under orders from General Philip H. Sheridan, raided the Kickapoo camps in Mexico. The captured Kickapoo were forcibly removed to Indian Territory.[79]

In the August 1890 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, submitted by Indian Agent Col. S.L. Patrick, the total Kickapoo reservation population was counted at 325.[23] Reservation acreage was reported as approximately200,000 acres (810 km2; 310 sq mi), west of the Sac and Fox reservation. It was reported that $5,000 was appropriated annually for basic medical care, supplies and farming implements. The population was reported as good farmers.[24]

The Kickapoo were first approached by the Commission, with Lucius Fairchild as Chairman, in October 1889. The tribe was not interested in allotments.[80] On June 27, 1890, the Commission under Jerome returned to negotiate with the Kickpoo. The tribe had since been under advisement by Cherokee Chief Joel B. Mayes, and once again rebuffed the Commission.[81] In June 1891, the Commission returned to negotiate with the tribe. The Kickapoo refused to anger the Great Spirit by ceding their land.[82]

Jerome moved the negotiations to Washington, D.C. Okanokasie, Keshokame and five headmen were authorized to represent the tribe. A white man named John T. Hill acted as tribal advisor.[83] On September 9, 1891 in Washington, D.C., the Kickapoo signed the Agreement with the Kickapoo (1891) to cede their lands for $64,650 (about 32 cents per acre). Their allotments were 80 acres (0.32 km2; 0.13 sq mi) per person. and not to exceed a total of 300 allotments. Each allotment over the 300 limit would result in $50 being deducted from the $64,650 paid to the tribe. The allotments were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 90 days of Congressional ratification of the agreement. If any member failed to make the selection within that time frame, the selection would be made for them by the local agent. Land patents to the individual allotments land were to be held in a tax-free trust for the benefit of the allottees, for a period of twenty-five years. Joseph Whipple, testified that he was chosen by the Kickapoo as interpreter because of his fluency with the tribal language. He also attested that he was neither able to read nor write, and that what he conveyed to the Kickapoo was a translation of what had been read to him by Sayre. Congress ratified the agreement March 1893.[84]

Quaker field matron Elizabeth Test reported in August 1894, that most Kickapoo did not understand that the agreement meant they were giving up their land. With the assistance of advocate Charles C. Painter of the Indian Rights Association, the Kickapoo presented their case to the House Committ