Marshall is a city in the U.S. state of Texas.[4] It is the county seat of Harrison County and a cultural and educational center of the Ark-La-Tex region. At the 2020 U.S. census, the population of Marshall was 23,392.[5] The population of the Greater Marshall area, comprising all of Harrison County, was 65,631 in 2010[6] and 66,726 in 2018.[7]

Marshall and Harrison County were important political and production areas of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. This area of Texas was developed for cotton plantations. Planters brought slaves with them from other regions or bought them in the domestic slave trade. The county had the highest number of slaves in the state, and East Texas had a higher proportion of slaves than other regions of the state. The wealth of the county and city depended on slave labor and the cotton market.[8]

The late 19th century until the mid-20th century, Marshall developed as a large railroad center of the Texas and Pacific Railway. Following World War II, activists in the city's substantial African-American population worked to create social change through the Civil Rights Movement, with considerable support from the historically black colleges and universities in the area.

The city is known for holding one of the largest light festivals in the United States, the "Wonderland of Lights".[9][10][11] It identifies as the self-proclaimed "Pottery Capital of the World", for its sizable pottery industry.[12][13] Marshall is referred to by various nicknames: the "Cultural Capital of East Texas",[14] the "Gateway of Texas", the "Athens of Texas",[15] the "City of Seven Flags",[16][17] and "Center Stage", a branding slogan adopted by the Marshall Convention and Visitors Bureau.

The city was founded in 1841 as the seat of Harrison County after failed attempts to establish a county seat on the Sabine River. It was incorporated in 1843.[15] The Republic of Texas decided to choose the land donated for the seat by Peter Whetstone and Isaac Van Zandt after Whetstone had proven that the hilly location had a good water source.

The city quickly became a major city in the state because of its position as a gateway to Texas; it was on the route of several major stagecoach lines. Later, one of the first railroad lines constructed into Texas ran through it.

The founding of several colleges, including a number of seminaries, teaching colleges, and incipient universities, earned Marshall the nickname "the Athens of Texas", in reference to the ancient Greek city-state. The city's growing importance was confirmed when Marshall was linked by a telegraph line to New Orleans; it was the first city in Texas to have a telegraph service.[18]

By 1860, Marshall was the fourth-largest city in Texas and the seat of its richest county. Developing the land for cotton plantations, county planters held more slaves here than in any other county in the state. Many planters and other whites were strongly against the Union because of their investment in slavery.

When Governor Sam Houston refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederate States of America, Marshall's Edward Clark was sworn in as governor.[19] Pendleton Murrah, Texas's third Confederate governor, was also from Marshall.

The city became a major Confederate supply depot and manufacturer of gunpowder for the Confederate Army.[20] It hosted three conferences of Trans-Mississippi and Indian Territory leaders.

The exiled Confederate government of Missouri established Marshall as its temporary capital.[18] The city took the nickname of the "City of Seven Flags".[17] This was a nod to the flag of Missouri, in addition to the six flags of the varying nations and republics that have flown over the city.

Also during the Civil War, after the fall of Vicksburg, Marshall became the seat of Confederate civil authority and headquarters of the Trans-Mississippi Postal Department. The city may have been the intended target of a failed Union advance that was rebuffed at Mansfield, Louisiana.

Toward the end of the American Civil War, the Confederate government had $9.0 million in treasury notes and $3.0 million in postage stamps shipped to Marshall.[21] They may have intended Marshall as the destination of a government preparing to flee from advancing armies.

Marshall was occupied by Union forces on June 17, 1865.[22] During Reconstruction, the city was home to an office of the Freedmen's Bureau and was the base for federal troops in the region.[23] In 1873 the Methodist Episcopal Church founded Wiley College to educate freedmen. African Americans came to the city seeking opportunities and protection until 1878.

Although freedmen comprised the majority of voters in the county and supported the Republican Party, establishing a bi-racial government, in the post-Reconstruction era, the White Citizens Party, led by former Confederate General Walter P. Lane and his brother George, took control of the city and county governments by fraud and intimidation at elections.[24] Their militia ran Unionists, Republicans and many African Americans out of town. The Lanes ultimately declared Marshall and Harrison County "redeemed" from Union and African-American control.[25]

Despite this, the African-American community continued to progress. The historically black Bishop College was founded in 1881, and Wiley College was certified by the Freedman's Aid Society in 1882.

Marshall's "Railroad Era" began in the early 1870s. Harrison County citizens voted to offer a $300,000 bond subsidy,[20] and the City of Marshall offered to donate land north of the downtown to the Texas and Pacific Railway if the company would establish a center in Marshall. T&P President Jay Gould accepted the business incentive, locating the T&P's workshops and general offices for Texas in Marshall. The city immediately had a population explosion from workers attracted to the potential for new jobs there.[18]

By 1880, the city was one of the South's largest cotton markets, with crops and other products shipped by the railroad. The city's prosperity attracted new businesses: J. Weisman and Co. opened here as the first department store in Texas.[26] When one light bulb was installed in the Texas and Pacific Depot, Marshall became the first city in Texas to have electricity. During this period of wealth, many of the city's now historic homes were constructed. The city's most prominent industry, pottery manufacturing, began with the establishment of Marshall Pottery in 1895.

Despite the prosperity of the railroad era, some city residents struggled with poverty. Blacks were severely discriminated against under what was known as Jim Crow laws and customs. At the turn of the 20th century, the Democratic-dominated state legislature passed segregation laws and disenfranchised most blacks and Hispanics, as did all the states of the former Confederacy in this period. These minorities were essentially excluded from the political system for more than 60 years. Unable to vote, they were also excluded from juries and suffered injustices from all-white juries. In addition, from 1877 to 1950, Harrison County had 14 lynchings, most in the early 20th century, and more than any other county in Texas.

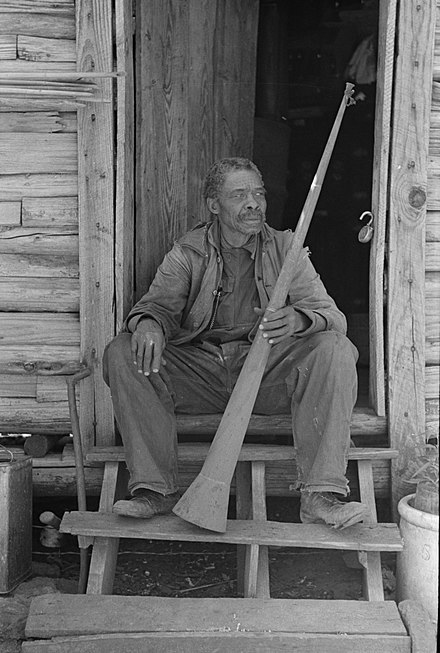

In the rural areas of Harrison County, more interaction occurred between whites and African-Americans than in the city, and whites and blacks were often neighbors. However, Jim Crow rules were strongly imposed on African-Americans.

In 1909, a field of natural gas was discovered near Caddo Lake; it was exploited to supply city needs.[27] Under the leadership of John L. Lancaster, the Texas and Pacific Railway enjoyed its height of success during the first half of the 20th century. Marshall's ceramics industry expanded to the point that the city was called by boosters the "Pottery Capital of the World".[12][13]

In 1930, what was then the largest oil field in the world was discovered at nearby Kilgore. The first student at Marshall High School to have a car was Lady Bird Johnson, a kind of progress that excited many students.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, children of both races were forced into accepting the law of racial segregation in the state. Marshall resident George Dawson became a writer late in life when he learned to read and write at age 98. He described his childhood under segregation in his memoir Life Is So Good(2013), written with Richard Glaubman. He said that in some instances, he and other Blacks resisted the demands of Jim Crow. For instance, he rejected one employer who expected him to eat with her dogs.

As blacks were being excluded from politics and tensions rose, more lynchings of black men took place, a form of extrajudicial punishment and social control. Beginning in the late 19th century, a total of 14 Black men were lynched in the county, the third-highest total in the state.[28] Suspects were often brought to Marshall for the lynchings, or taken from the county jail before trial and hanged in the courthouse square for maximum public effect of terrorizing the black population. Between October 1903 and August 1917, at least 12 black men were lynched in Marshall.[29][30][31][32] Not all instances of lynching were documented, so there may have been others.

In the early and mid-20th century, Marshall's traditionally black colleges, Wiley and Bishop, were thriving intellectual and cultural centers. The writer Melvin B. Tolson, who was part of the Harlem Renaissance in New York City, taught at Wiley College.[33] Painter Samuel Countee, a Texas-born student of Bishop College in the mid-1930s, exhibited at the Harmon Exhibitions in 1935–1937 and won a scholarship to study at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Countee had a successful career as a teacher and artist in the New York City area, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Inspired by the teachings of professors such as Tolson, students and former students of the colleges mobilized to challenge and dismantle Jim Crow laws and institutions in the 1950s and 1960s. Fred Lewis, as the secretary of the Harrison County National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), challenged the White Citizens Party in Harrison County, which had the oldest chapter in Texas, and the laws the party supported. This suit overturned Jim Crow in the county with the Perry v. Cyphers ruling. Heman Sweatt, a Wiley graduate, tried to enroll in the University of Texas at Austin Law School, but was denied entry because of his race. He sued and the United States Supreme Court ordered the desegregation of postgraduate studies in public universities in Texas in its ruling in Sweatt v. Painter (1950). James Farmer, another Wiley graduate, became an organizer of the Freedom Rides and a founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which was active throughout the South.

The Civil Rights Movement reached into the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. In the 1960s, students organized the first sit-ins in Texas,[34] in the rotunda of the county courthouse on Whetstone Square. They protested continuing segregation of public schools. This governmental practice had been declared unconstitutional in 1954 by the US Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education. In 1970, all Marshall public schools were finally integrated.

Also in that year, Carolyn Abney became the first woman to be elected to the Marshall City Commission. In April 1975, nearly a decade after passage of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965, local businessman Sam Birmingham became the first African American to be elected to the city commission. In the 1980s, he was elected as the city's first African-American mayor. Birmingham retired in 1989 for health concerns and was succeeded by his wife, Jean Birmingham.

Marshall's railroad industry declined during the restructuring of the industry; most trains were converted to diesel fuel, and many lines merged. Construction of the Interstate Highway System after World War II and expansion of trucking, plus the increase in airline traffic, also led to railway declines. The T&P shops closed