The Mexican Army (Spanish: Ejército Mexicano) is the combined land and air branch and is the largest part of the Mexican Armed Forces; it is also known as the National Defense Army.

The Army is under the authority of the Secretariat of National Defense or SEDENA and is headed by the Secretary of National Defence.

It was the first army to adopt (1908) and use (1910) a self-loading rifle, the Mondragón rifle. The Mexican Army has an active duty force of 261,773 men and women in 2024.

In the prehispanic era, there were many indigenous tribes and highly developed city-states in what is now known as central Mexico. The most advanced and powerful kingdoms were those of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan, which comprised populations of the same ethnic origin and were politically linked by an alliance known as the Triple Alliance; colloquially these three states are known as the Aztec. They had a center for higher education called the Calmecac in Nahuatl, this was where the children of the Aztec priesthood and nobility receive rigorous religious and military training and conveyed the highest knowledge such as: doctrines, divine songs, the science of interpreting codices, calendar skills, memorization of texts, etc. In Aztec society, it was compulsory for all young males, nobles as well as commoners, to join part of the armed forces at the age of 15. Recruited by regional and clan groups (calpulli) the conscripts were organized in units of about 8,000 men (Xiquipilli). These were broken down into 400 strong sub-units. Aztec nobility (some of whom were the children of commoners who had distinguished themselves in battle) led their own serfs on campaign.[3]

Itzcoatl "Obsidian Serpent" (1381–1440), fourth king of Tenochtitlán, organized the army that defeated the Tepanec of Azcapotzalco, freeing his people from their dominion. His reign began with the rise of what would become the largest empire in Mesoamerica. Then Moctezuma Ilhuicamina "The arrow to the sky" (1440–1469) came to extend the domain and the influence of the monarchy of Tenochtitlán. He began to organize trade to the outside regions of the Valley of Mexico. This was the Mexica ruler who organized the alliance with the lordships of Texcoco and Tlacopan to form the Triple Alliance.

The Aztec established the Flower Wars as a form of worship; these, unlike the wars of conquest, were aimed at obtaining prisoners for sacrifice to the sun. Combat orders were given by kings (or Lords) using drums or blowing into a sea snail shell that gave off a sound like a horn. Giving out signals using coats of arms was very common. For combat outside of cities, they would organize several groups, only one of which would be involved in action, while the others remained on the alert. When attacking enemy cities, they usually divided their forces into three equal-sized wings, which simultaneously assaulted different parts of the defences – this enabled the leaders to determine which division of warriors had distinguished themselves the most in combat.[4]

During the 18th century the Spanish colonial forces in the greater Mexico region consisted of regular "Peninsular" regiments sent from Spain itself, augmented by locally recruited provincial and urban militia units of infantry, cavalry and artillery. A few regular infantry and dragoon regiments (e.g. the Regimiento de Mexico) were recruited within Mexico and permanently stationed there.[5] Mounted units of soldados de cuera (so called from the leather protective clothing that they wore)[6] patrolled frontier and desert regions.[7]

In the early morning of 16 September 1810, the Army of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla initiated the independence movement. Hidalgo was followed by his loyal companions, among them Mariano Abasolo, and a small army equipped with swords, spears, slingshots and sticks. Captain General Ignacio Allende was the military brains of the insurgent army in the first phase of the War of Independence and secured several victories over the Spanish Royal Army. Their troops were about 5,000 strong and were later joined by squadrons of the Queen's Regiment where its members in turn contributed infantry battalions and cavalry squadrons to the insurrection cause.

The Spaniards saw that it was important to defend the Alhóndiga de Granaditas public granary in Guanajuato, which maintained the flow of water, weapons, food and ammunition to the Spanish Royal Army. The insurgents entered Guanajuato and proceeded to lay siege to the Alhóndiga. The insurgents suffered heavy casualties until Juan Jose de los Reyes, the Pípila, fitted a slab of rock on his back to protect himself from enemy fire and crawled to the large wooden door of the Alhóndiga with a torch in hand to set it on fire. With this stunt, the insurgents managed to bring down the door and enter the building and overrun it. Hidalgo headed to Valladolid (now Morelia), which was captured with little opposition. While the Insurgent Army was, by then, over 60,000 strong, it was mostly formed of poorly armed men with arrows, sticks and tillage tools – it had a few guns, which had been taken from Spanish stocks.

In Aculco, the Royal Spanish forces under the command of Felix Maria Calleja, Count of Calderón, and Don Manuel de Flon (and comprising 200 infantrymen, 500 cavalry and 12 cannons) defeated the insurgents, who lost many men as well as the artillery they had obtained at Battle of Monte de las Cruces. On 29 November 1810, Hidalgo entered Guadalajara, the capital of Nueva Galicia, where he organized his government and the Insurgent Army; he also issued a decree abolishing slavery.

At Calderon Bridge (Puente de Calderón) near the city of Guadalajara, insurgents held a hard-fought battle with the royalists. During the fierce fighting, one of the insurgents' ammunition wagons exploded, which led to their defeat. The insurgents lost all their artillery, much of their equipment and the lives of many men.

At the Wells of Baján (Norias de Baján) near Monclova, Coahuila, a former royalist named Ignacio Elizondo, who had joined the insurgent cause, betrayed them and seized Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, Ignacio Allende, Juan Aldama, José Mariano Jiménez and the rest of the entourage. They were brought to the city of Chihuahua where they were tried by a military court and executed by firing squad on 30 July 1811. Hidalgo's death resulted in a political vacuum for the insurgents until 1812. Meanwhile, the royalist military commander, General Félix María Calleja, continued to pursue rebel troops. The fighting evolved into guerrilla warfare.

The next major rebel leader was the priest José María Morelos y Pavón, who had formerly led the insurgent movement alongside Hidalgo. Morelos fortified the port of Acapulco and took the city of Chilpancingo. Along the way, Morelos, was joined by Leonardo Bravo, his son Nicholas and his brothers Max, Victor and Miguel Bravo.

Morelos conducted several campaigns in the south, managing to conquer much of the region as he gave orders to the insurgents to promote the writing of the first constitution for the new Mexican nation: the Constitution of Apatzingan, which was drafted in 1814. In 1815, Morelos was apprehended and executed by firing squad. His death concluded the second phase of the Mexican War for Independence. From 1815 to 1820, the independence movement became sluggish; it was briefly reinvigorated by Francisco Javier Mina and Pedro Moreno, who were both quickly apprehended and executed.

It was not until late 1820, when Agustín de Iturbide, one of the most bloodthirsty enemies of the insurgents, established relations with Vicente Guerrero and Guadalupe Victoria, two of the rebel leaders. Guerrero and Victoria supported Iturbide's plan for Mexican independence, El Plan de Iguala and Iturbide was appointed commander of the Ejército Trigarante, or The Army of the Three Guarantees. With this new alliance, they were able to enter Mexico City on 27 September 1821, which concluded the Mexican War for Independence.

The Pastry War was the first French intervention in Mexico. Following the widespread civil disorder that plagued the early years of the Mexican republic, fighting in the streets destroyed a great deal of personal property. Foreigners whose property was damaged or destroyed by rioters or bandits were usually unable to obtain compensation from the government, and began to appeal to their own governments for help.

In 1838, a French pastry cook, Monsieur Remontel, claimed that his shop in the Tacubaya district of Mexico City had been ruined in 1828 by looting Mexican officers. He appealed to France's King Louis-Philippe (1773–1850). Coming to its citizen's aid, France demanded 600,000 pesos in damages. This amount was extremely high when compared to an average workman's daily pay, which was about one peso. In addition to this amount, Mexico had defaulted on millions of dollars worth of loans from France. Diplomat Baron Deffaudis gave Mexico an ultimatum to pay, or the French would demand satisfaction. When the payment was not forthcoming from president Anastasio Bustamante (1780–1853), the king sent a fleet under Rear Admiral Charles Baudin to declare a blockade of all Mexican ports from Yucatán to the Rio Grande, to bombard the Mexican fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, and to seize the port of Veracruz. Virtually the entire Mexican Navy was captured at Veracruz by December 1838. Mexico declared war on France.

With trade cut off, the Mexicans began smuggling imports into Corpus Christi, Texas, and then into Mexico. Fearing that France would blockade Texan ports as well, a battalion of men of the Republic of Texas force began patrolling Corpus Christi Bay to stop Mexican smugglers. One smuggling party abandoned their cargo of about a hundred barrels of flour on the beach at the mouth of the bay, thus giving Flour Bluff its name. The United States, ever watchful of its relations with Mexico, sent the schooner Woodbury to help the French in their blockade. Talks between the French Kingdom and the Texan nation occurred and France agreed not to offend the soil or waters of the Republic of Texas. With the diplomatic intervention of the United Kingdom, eventually President Bustamante promised to pay the 600,000 pesos and the French forces withdrew on 9 March 1839.

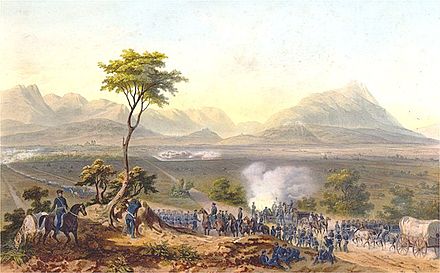

U.S. territorial expansion under Manifest Destiny in the 19th century had reached the banks of the Rio Grande, which prompted Mexican president José Joaquín de Herrera to form an army of 6,000 men to defend the Mexican northern frontier from the expansion of the neighboring country. In 1845, Texas, a former Mexican territory that had broken away from Mexico by rebellion, was annexed into the United States. In response to this, the minister of Mexico in the U.S., Juan N. Almonte called for his Letters of Recognition and returned to Mexico; hostilities promptly ensued. On 25 April 1846, a Mexican force under colonel Anastasio Torrejon surprised and defeated a U.S. squadron at the Rancho de Carricitos in Matamoros in an event that would latter be known as the Thornton Skirmish; this was the pretext that U.S. president James K. Polk used to persuade the U.S. congress into declaring a state of war against Mexico on 13 May 1846. U.S. Army captain John C. Frémont, with about sixty well-armed men, had entered the California territory in December 1845 before the war had been official and was marching slowly to Oregon when he received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent; thus began a chapter of the war known as the Bear Flag Revolt.

On 20 September 1846, the U.S. launched an attack on Monterrey, which fell after 5 days. After this U.S. victory, hostilities were suspended for 7 weeks, allowing Mexican troops to leave the city with their flags displayed in full honors as U.S. soldiers regrouped and regained their losses. In August 1846, Commodore David Conner and his squadron of ships were in Veracruzian waters; he tried, unsuccessfully, to seize the Fort of Alvarado, which was defended by the Mexican Navy. The Americans were forced to relocate to Antón Lizardo. In confronting resistance and fortifications at the port of Veracruz, the U.S. Army and Marines implemented an intense bombardment of the city from 22 to 26 March 1847, causing about five hundred civilian deaths and significant damage to homes, buildings, and merchandise. Gener