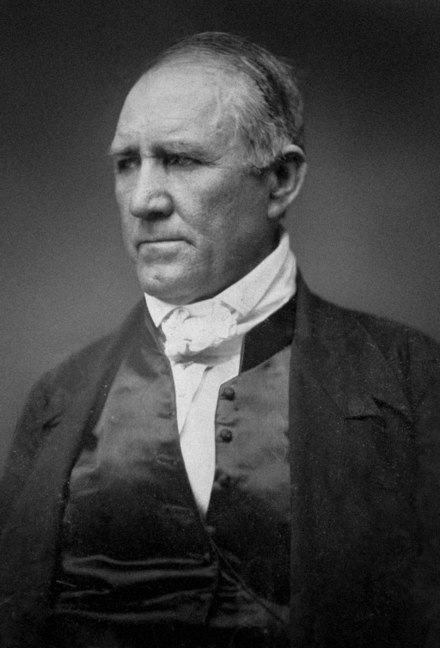

The Battle of San Jacinto (Spanish: Batalla de San Jacinto), fought on April 21, 1836, in present-day La Porte and Deer Park, Texas, was the final and decisive battle of the Texas Revolution. Led by General Samuel Houston, the Texan Army engaged and defeated General Antonio López de Santa Anna's Mexican army in a fight that lasted just 18 minutes. A detailed, first-hand account of the battle was written by General Houston from the headquarters of the Texan Army in San Jacinto on April 25, 1836.[3] Numerous secondary analyses and interpretations have followed.

General Santa Anna, the president of Mexico, and General Martín Perfecto de Cos both escaped during the battle. Santa Anna was captured the next day on April 22 and Cos on April 24. After being held for about three weeks as a prisoner of war, Santa Anna signed the peace treaty that dictated that the Mexican army leave the region, paving the way for the Republic of Texas to become an independent country. These treaties did not necessarily recognize Texas as a sovereign nation but stipulated that Santa Anna was to lobby for such recognition in Mexico City. Sam Houston became a national celebrity, and the Texans' rallying cries from events of the war, "Remember the Alamo" and "Remember Goliad", became etched into Texan history and legend.

General Antonio López de Santa Anna was a proponent of governmental federalism when he helped oust Mexican President Anastasio Bustamante in December 1832. Upon his election as president in April 1833,[4] Santa Anna switched his political ideology and began implementing centralist policies that increased the authoritarian powers of his office.[5] His abrogation of the Constitution of 1824, correlating with his abolishing local-level authority over Mexico's state of Coahuila y Tejas (Coahuila and Texas), became a flashpoint in the growing tensions between the central government and its Tejano and Anglo citizens in Texas. While in Mexico City awaiting a meeting with Santa Anna, Texian empresario Stephen F. Austin wrote to the ayuntamiento (city council) of Béxar (now San Antonio) urging a break-away state. In response, the Mexican government kept him imprisoned for most of 1834.[6][7]

Colonel Juan Almonte was appointed director of colonization in Texas,[8] ostensibly to ease relations with the colonists and mitigate their anxieties about Austin's imprisonment.[9] He delivered promises of self-governance and conveyed regrets that the Mexican Congress deemed it constitutionally impossible for Texas to be a separate state. Behind the rhetoric, his covert mission was to identify the local power brokers, obstruct any plans for rebellion, and supply the Mexican government with data that would be of use in a military conflict. For nine months in 1834, under the guise of serving as a government liaison, Almonte traveled through Texas and compiled an all-encompassing intelligence report on the population and its environs, including an assessment of their resources and defense capabilities.[10]

In consolidating his power base, Santa Anna installed General Martín Perfecto de Cos as the governing military authority over Texas in 1835.[11][12] Cos established headquarters in San Antonio on October 9, triggering what became known as the Siege of Béxar.[13] After two months of trying to repel the Texian forces, Cos raised a white flag on December 9 and signed surrender terms two days later.[14] The surrender of Cos effectively removed the occupying Mexican army from Texas. Many believed the war was over, and volunteers began returning home.[15]

In compliance with orders from Santa Anna, Mexico's Minister of War José María Tornel issued his December 30 "Circular No. 5", often referred to as the Tornel Decree, aimed at dealing with United States intervention in the uprising in Texas. It declared that foreigners who entered Mexico for the purpose of joining the rebellion were to be treated as "pirates", to be put to death if captured. In adding "since they are not subjects of any nation at war with the republic nor do they militate under any recognized flag," Tornel avoided declaring war on the United States.[16][17]

The Mexican Army of Operations numbered 6,019 soldiers[18] and was spread out over 300 miles (480 km) on its march to Béxar. General Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma was put in command of the Vanguard of the Advance that crossed into Texas.[19] Santa Anna and his aide-de-camp Almonte[20] forded the Rio Grande at Guerrero, Coahuila on February 16, 1836,[21] with General José de Urrea and 500 more troops following the next day at Matamoros.[22] Béxar was captured on February 23, and when the assault commenced, attempts at negotiation for surrender were initiated from inside the fortress. William B. Travis, the garrison commander, sent Albert Martin to request a meeting with Almonte, who replied that he did not have the authority to speak for Santa Anna.[23] Colonel James Bowie dispatched Green B. Jameson with a letter, translated into Spanish by Juan Seguín, requesting a meeting with Santa Anna, who immediately refused. Santa Anna did, however, extend an offer of amnesty to Tejanos inside the fortress. Alamo non-combatant survivor Enrique Esparza said that most Tejanos left when Bowie advised them to take the offer.[24]

Cos, in violation of his surrender terms, forded into Texas at Guerrero on February 26 to join with the main army at Béxar.[25] Urrea proceeded to secure the Gulf Coast and was victorious in two skirmishes with Texian detachments serving under Colonel James Fannin at Goliad. On February 27 a foraging detachment under Frank W. Johnson at San Patricio was attacked by Urrea. Sixteen were killed and twenty-one taken prisoner, but Johnson and four others escaped.[26][27] Urrea sent a company in search of James Grant and Plácido Benavides who were leading a company of Anglos and Tejanos towards an invasion of Matamoros. The Mexicans ambushed a group of Texians, killing Grant and most of the company. Benavides and 4 others escaped, and 6 were taken prisoner.[28][29]

The Convention of 1836 met at Washington-on-the-Brazos on March 1.[30] The following day, Sam Houston's 42nd birthday, the 59 delegates signed the Texas Declaration of Independence and chose an ad interim government.[30][31] When news of the declaration reached Goliad, Benavides informed Fannin that in spite of his opposition to Santa Anna, he was still loyal to Mexico and did not wish to help Texas break away. Fannin discharged him from his duties and sent him home.[32] On March 4, Houston's military authority was expanded to include "the land forces of the Texian army both Regular, Volunteer, and Militia."[33]

At 5 a.m. on March 6, the Mexican troops launched their final assault on the Alamo. After a vicious 90 minute battle, with immense losses to the Mexican forces, the guns fell silent; the Alamo had fallen.[34] Survivors Susanna Dickinson, her daughter Angelina, Travis' slave Joe, and Almonte's cook Ben were spared by Santa Anna and sent to Gonzales, where Texian volunteers had been assembling.[35]

The same day that Mexican troops departed Béxar, Houston arrived in Gonzales and informed the 374 volunteers (some without weapons) gathered there that Texas was now an independent republic.[36] Just after 11 p.m. on March 13, Susanna Dickinson and Joe brought news that the Alamo garrison had been defeated and the Mexican army was marching towards Texian settlements. A hastily convened council of war voted to evacuate the area and retreat. The evacuation commenced at midnight and happened so quickly that many Texian scouts were unaware the army had moved on. Everything that could not be carried was burned, and the army's only two cannon were thrown into the Guadalupe River.[37] When Ramírez y Sesma reached Gonzales the morning of March 14, he found the buildings still smoldering.[38]

Most citizens fled on foot, many carrying their small children. A cavalry company led by Seguín and Salvador Flores were assigned as rear guard to evacuate the more isolated ranches and protect the civilians from attacks by Mexican troops or Indians.[39] The further the army retreated, the more civilians joined the flight.[40] For both armies and the civilians, the pace was slow; torrential rains had flooded the rivers and turned the roads into mud pits.[41]

As news of the Alamo's fall spread, volunteer ranks swelled, reaching about 1,400 men by March 19.[41] Houston learned of Fannin's surrender on March 20 and realized his army was the last hope for an independent Texas. Concerned that his ill-trained and ill-disciplined force would be good for only one battle, and aware that his men could easily be outflanked by Urrea's forces, Houston continued to avoid engagement, to the immense displeasure of his troops.[42] By March 28, the Texian army had retreated 120 miles (190 km) across the Navidad and Colorado Rivers.[43] Many troops deserted; those who remained grumbled that their commander was a coward.[42]

On March 31, Houston paused his men at Groce's Landing on the Brazos River.[Note 1] Two companies that refused to retreat further were assigned to guard the crossing.[44] For the next two weeks, the Texians rested, recovered from illness, and, for the first time, began practicing military drills. While there, two cannon, known as the Twin Sisters, arrived from Cincinnati, Ohio.[45] Interim Secretary of War Thomas Rusk joined the camp, with orders from President David G. Burnet to replace Houston if he refused to fight. Houston quickly persuaded Rusk that his plans were sound.[45] Secretary of State Samuel P. Carson advised Houston to continue retreating all the way to the Sabine River, where more volunteers would likely flock from the United States and allow the army to counterattack.[Note 2][46] Unhappy with everyone involved, Burnet wrote to Houston: "The enemy are laughing you to scorn. You must fight them. You must retreat no further. The country expects you to fight. The salvation of the country depends on your doing so."[45] Complaints within the camp became so strong that Houston posted notices that anyone attempting to usurp his position would be court-martialed and shot.[47]

Santa Anna and a smaller force had remained in Béxar. After receiving word that acting President Miguel Barragán had died, Santa Anna seriously considered returning to Mexico City to solidify his position. Fear that Urrea's victories would position him as a political rival convinced Santa Anna to remain in Texas to personally oversee the final phase of the campaign.[48] He left on March 29 to join Ramírez y Sesma, leaving only a small force to hold Béxar.[49] At dawn on April 7, their combined force marched into San Felipe and captured a Texian soldier, who informed Santa Anna that the Texians planned to retreat further if the Mexican army crossed the Brazos River.[50] Unable to cross the Brazos because of the small company of Texians barricaded at the river crossing, on April 14 a frustrated Santa Anna led a force of about 700 troops to capture the interim Texas government.[51][52] Government officials fled mere hours before Mexican troops arrived in Harrisburgh (now Harrisburg, Houston) and Santa Anna sent Almonte with 50 cavalry to intercept them in New Washington. Almonte arrived just as Burnet shoved off in a rowboat, bound for Galveston Island. Although the boat was still within range of their weapons, Almonte ordered his men to hold their fire so as not to endanger Burnet's family.[53]

At this point, Santa Anna believed the rebellion was in its final death throes. The Texian government had been forced off the mainland, with no way to communicate with its army, which had shown no interest in fighting. He determined to block the Texian army's retreat and put a decisive end to the war.[53] Almonte's scouts incorrectly reported that Houston's army was going to Lynchburg Crossing on Buffalo Bayou, in preparation for joining the government in Galveston, so Santa Anna ordered Harrisburgh burned and pressed on towards