The Battle of Salamis (/ˈsæləmɪs/ sal-ə-MISS) was a naval battle fought in 480 BC, between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles, and the Achaemenid Empire under King Xerxes. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was fought in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens, and marked the high point of the second Persian invasion of Greece. It was arguably the largest naval battle of the ancient world,[7] and marked a turning point in the invasion.[8]

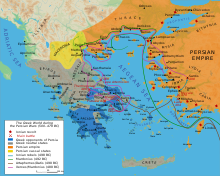

To block the Persian advance, a small force of Greeks blocked the pass of Thermopylae, while an Athenian-dominated allied navy engaged the Persian fleet in the nearby straits of Artemisium. In the resulting Battle of Thermopylae, the rearguard of the Greek force was annihilated, while in the Battle of Artemisium the Greeks suffered heavy losses and retreated after the loss at Thermopylae. This allowed the Persians to conquer Phocis, Boeotia, Attica and Euboea. The allies prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth while the fleet was withdrawn to nearby Salamis Island.

Although heavily outnumbered, the Greeks were persuaded by Athenian general Themistocles to bring the Persian fleet to battle again, in the hope that a victory would prevent naval operations against the Peloponnese. Persian king Xerxes was also eager for a decisive battle. As a result of subterfuge on the part of Themistocles (which included a message directly sent to Xerxes letting him know that much of the Greek fleet was stationed at Salamis), the Persian navy rowed into the Straits of Salamis and tried to block both entrances. In the cramped waters, the great Persian numbers were an active hindrance, as ships struggled to maneuver and became disorganized. Seizing the opportunity, the Greek fleet formed in line and achieved a decisive victory.

Xerxes retreated to Asia with much of his army, leaving Mardonius to complete the conquest of Greece. The following year the remainder of the Persian army was decisively defeated at the Battle of Plataea and the Persian navy at the Battle of Mycale. The Persians made no further attempts to conquer the Greek mainland. The battles of Salamis and Plataea thus mark a turning point in the course of the Greco-Persian Wars as a whole; from then onward, the Greek poleis would take the offensive.

The Greek city-states of Athens and Eretria had supported the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt against the Persian Empire of Darius I in 499-494 BC, led by the satrap of Miletus, Aristagoras. The Persian Empire was still relatively young, and prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples.[10][11]Moreover, Darius was a usurper, and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule.[10] The Ionian revolt threatened the integrity of his empire, and Darius thus vowed to punish those involved (especially those not already part of the empire).[12][13] Darius also saw the opportunity to expand his empire into the fractious world of Ancient Greece.[13] A preliminary expedition under Mardonius, in 492 BC, to secure the land approaches to Greece ended with the conquest of Thrace and forced Macedon to become a client kingdom of Persia.[14]

In 491 BC, Darius sent emissaries to all the Greek city-states, asking for a gift of 'earth and water' in token of their submission to him.[15] Having had a demonstration of his power the previous year, the majority of the Greek cities duly obliged. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well.[15] This meant that Sparta was also now effectively at war with Persia.[15]

Darius thus put together an amphibious task force under Datis and Artaphernes in 490 BC, which attacked Naxos, before receiving the submission of the other Cycladic Islands. The task force then moved on Eretria, which it besieged and destroyed.[16] Finally, it moved to attack Athens, landing at the bay of Marathon, where it was met by a heavily outnumbered Athenian army. At the ensuing Battle of Marathon, the Athenians won a remarkable victory, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Persian army to Asia.[17]

Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.[11] Darius then died whilst preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I.[18] Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt, and very quickly restarted the preparations for the invasion of Greece.[19] Since this was to be a full-scale invasion, it required long-term planning, stock-piling and conscription.[19] Xerxes decided that the Hellespont would be bridged to allow his army to cross to Europe, and that a canal should be dug across the isthmus of Mount Athos (rounding which headland, a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC).[20] These were both feats of exceptional ambition, which would have been beyond any other contemporary state.[20] By early 480 BC, the preparations were complete, and the army which Xerxes had mustered at Sardis marched towards Europe, crossing the Hellespont on two pontoon bridges.[21]

The Athenians had also been preparing for war with the Persians since the mid-480s BC, and in 482 BC the decision was taken, under the guidance of the Athenian politician Themistocles, to build a massive fleet of triremes that would be necessary for the Greeks to fight the Persians.[22] However, the Athenians did not have the manpower to fight on land and sea; and therefore combatting the Persians would require an alliance of Greek city states. In 481 BC, Xerxes sent ambassadors around Greece asking for earth and water, but made the very deliberate omission of Athens and Sparta.[23] Support thus began to coalesce around these two leading states. A congress of city states met at Corinth in late autumn of 481 BC,[24] and a confederate alliance of Greek city-states was formed. It had the power to send envoys asking for assistance and to dispatch troops from the member states to defensive points after joint consultation. This was remarkable for the disjointed Greek world, especially since many of the city-states in attendance were still technically at war with each other.[25]

Initially the 'congress' agreed to defend the narrow Vale of Tempe, on the borders of Thessaly, and thereby block Xerxes's advance.[26] However, once there, they were warned by Alexander I of Macedon that the vale could be bypassed through the pass by the modern village of Sarantaporo, and that the army of Xerxes was overwhelming, so the Greeks retreated.[27] Shortly afterward, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont. A second strategy was therefore adopted by the allies. The route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica and the Peloponnese) would require the army of Xerxes to travel through the very narrow pass of Thermopylae. This could easily be blocked by the Greek hoplites, despite the overwhelming numbers of Persians. Furthermore, to prevent the Persians bypassing Thermopylae by sea, the Athenian and allied navies could block the straits of Artemisium. This dual strategy was adopted by the congress.[28] However, the Peloponnesian cities made fall-back plans to defend the Isthmus of Corinth should it come to it, whilst the women and children of Athens had been evacuated en masse to the Peloponnesian city of Troezen.[29]

Famously, the much smaller Greek army held the pass of Thermopylae against the Persians for three days before being outflanked by a mountain path. Much of the Greek army retreated, before the Spartans and Thespians who had continued to block the pass were surrounded and killed.[30] The simultaneous Battle of Artemisium was up to that point a stalemate;[31] however, when news of Thermopylae reached them, the Allied fleet also retreated, since holding the straits of Artemisium was now a moot point.[32]