The Republic of Texas was annexed into the United States and admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico on March 2, 1836. It applied for annexation to the United States the same year, but was rejected by the United States Secretary of State. At that time, the majority of the Texian population favored the annexation of the Republic by the United States. The leadership of both major U.S. political parties (the Democrats and the Whigs) opposed the introduction of Texas — a vast slave-holding region — into the volatile political climate of the pro- and anti-slavery sectional controversies in Congress. Moreover, they wished to avoid a war with Mexico, whose government had outlawed slavery and refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of its rebellious northern province. With Texas's economic fortunes declining by the early 1840s, the President of the Texas Republic, Sam Houston, arranged talks with Mexico to explore the possibility of securing official recognition of independence, with the United Kingdom mediating.

In 1843, U.S. President John Tyler, then unaligned with any political party, decided independently to pursue the annexation of Texas in a bid to gain a base of support for another four years in office. His official motivation was to outmaneuver suspected diplomatic efforts by the British government for the emancipation of slaves in Texas, which would undermine slavery in the United States. Through secret negotiations with the Houston administration, Tyler secured a treaty of annexation in April 1844. When the documents were submitted to the U.S. Senate for ratification, the details of the terms of annexation became public and the question of acquiring Texas took center stage in the presidential election of 1844. Pro-Texas-annexation southern Democratic delegates denied their anti-annexation leader Martin Van Buren the nomination at their party's convention in May 1844. In alliance with pro-expansion northern Democratic colleagues, they secured the nomination of James K. Polk, who ran on a pro-Texas Manifest destiny platform.

In June 1844, the Senate, with its Whig majority, soundly rejected the Tyler–Texas treaty. Later that year, the pro-annexation Democrat Polk narrowly defeated anti-annexation Whig Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election. In December 1844, lame-duck President Tyler called on Congress to pass his treaty by simple majorities in each house. The Democratic-dominated House of Representatives complied with his request by passing an amended bill expanding on the pro-slavery provisions of the Tyler treaty. The Senate narrowly passed a compromise version of the House bill, designed to provide President-elect Polk the options of immediate annexation of Texas or new talks to revise the annexation terms of the House-amended bill.

On March 1, 1845, President Tyler signed the annexation bill, and on March 3 (his last full day in office), he forwarded the House version to Texas, offering immediate annexation. When Polk took office at noon the following day, he encouraged Texas to accept Tyler’s offer. Texas ratified the agreement with popular approval from Texians. The bill was signed by President Polk on December 29, 1845, accepting Texas as the 28th state of the Union. Texas formally joined the union on February 19, 1846, prompting the Mexican–American War in April of that year.

First mapped by Spain in 1519, for over 300 years Texas was part of the vast Spanish Empire seized by the Spanish conquistadores from its indigenous people.[1] The US-Spain border along the northern frontier of Texas took shape in the 1817–1819 negotiations between Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and the Spanish ambassador to the United States, Luis de Onís.[2] The boundaries of Texas were determined within the larger geostrategic struggle to demark the limits of the United States' extensive western lands and of Spain's vast possessions in North America.[3] The Florida Purchase Treaty of February 22, 1819[4][5] emerged as a compromise that excluded Spain from the lower Columbia River drainage basin, but established southern boundaries at the Sabine and Red Rivers, "legally extinguish[ing]" any American claims to Texas.[6][7] Nonetheless, Texas remained an object of fervent interest to American expansionists, among them Thomas Jefferson, who anticipated the eventual acquisition of its fertile lands.[8]

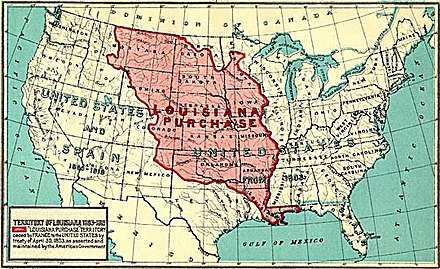

The Missouri crisis of 1819–1821 sharpened commitments to expansionism among the country's slaveholding interests, when the so-called Thomas proviso established the 36°30' parallel, imposing free-soil and slave-soil futures in the Louisiana Purchase lands.[9] While a majority of southern congressmen acquiesced to the exclusion of slavery from the bulk of the Louisiana Purchase, a significant minority objected.[10][11] Virginian editor Thomas Ritchie of the Richmond Enquirer predicted that with the proviso restrictions, the South would ultimately require Texas: "If we are cooped up on the north, we must have elbow room to the west."[12][13] Representative John Floyd of Virginia in 1824 accused Secretary of State Adams of conceding Texas to Spain in 1819 in the interests of Northern anti-slavery advocates, and so depriving the South of additional slave states.[14] Then-Representative John Tyler of Virginia invoked the Jeffersonian precepts of territorial and commercial growth as a national goal to counter the rise of sectional differences over slavery. His "diffusion" theory declared that with Missouri open to slavery, the new state would encourage the transfer of underutilized slaves westward, emptying the eastern states of bondsmen and making emancipation feasible in the old South.[15] This doctrine would be revived during the Texas annexation controversy.[16][17]

When Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821,[18] the United States did not contest the new republic's claims to Texas, and both presidents John Quincy Adams (1825–1829) and Andrew Jackson (1829–1837) persistently sought, through official and unofficial channels, to procure all or portions of provincial Texas from the Mexican government, without success.[19]

Spanish and indigenous immigrants, primarily from northeastern provinces of New Spain, began to settle Texas in the late 17th century. The Spanish constructed Catholic missions and presidios in what is today Louisiana, east Texas, and south Texas. The first missions were designed for the Tejas Indians, near Los Adaes. Soon thereafter, the San Antonio Missions were founded along the San Antonio River. The City of San Antonio, then known as San Fernando de Bexar, was founded in 1718. In the early 1760s, José de Escandón created five settlements along the Rio Grande River, including Laredo.

Anglo-American immigrants, primarily from the Southern United States, began emigrating to Mexican Texas in the early 1820s at the invitation of the Texas faction of the Coahuila y Tejas state government, which sought to populate the sparsely inhabited lands of its northern frontier for cotton production.[20][21] Colonizing empresario Stephen F. Austin managed the regional affairs of the mostly American-born population – 20% of them slaves[22] – under the terms of the generous government land grants.[23] Mexican authorities were initially content to govern the remote province through salutary neglect, "permitting slavery under the legal fiction of 'permanent indentured servitude', similar to Mexico's peonage system.[24]

A general lawlessness prevailed in the vast Texas frontier, and Mexico's laws went largely unenforced among the Anglo-American settlers. In particular, the prohibitions against slavery and forced labor, as well as the requirement that all settlers be Catholic or convert to Catholicism were ignored.[25][26] Mexican authorities, perceiving that they were losing control over Texas and alarmed by the unsuccessful Fredonian Rebellion of 1826, abandoned the policy of benign rule. New restrictions were imposed in 1829–1830, outlawing slavery throughout the nation and terminating further American immigration to Texas.[27][28] Military occupation followed, sparking local uprisings. Texas conventions in 1832 and 1833 submitted petitions for redress of grievances to overturn the restrictions, with limited success.[29] In 1835, an army under Mexican President Santa Anna entered its territory of Texas and abolished self-government. Texians responded by declaring their independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836. On April 20–21, rebel forces under Texas General Sam Houston defeated the Mexican army at the Battle of San Jacinto.[30][31] In June 1836 while held prisoner by the Texians, Santa Anna signed an agreement for Texas independence, but the Mexican government refused to ratify the agreement made under duress.[32] Texians, now de facto independent, recognized that their security and prosperity could never be achieved while Mexico denied the legitimacy of their revolution.[18]

In the years following independence, the migration of white settlers and importation of black slave labor into the vast republic was deterred by Texas's unresolved international status and the threat of renewed warfare with Mexico.[33] American citizens who considered migrating to the new republic perceived that "life and property were safer within the United States" than in an independent Texas.[34] In the 1840s, global oversupply had also caused a crash in the price of cotton, the country's main export commodity.[35] The situation led to labor shortages, reduced tax revenue, large national debts and a diminished Texas militia.[36][37]

The Anglo-American immigrants residing in newly independent Texas overwhelmingly desired immediate annexation by the United States.[38] But, despite his strong support for Texas independence from Mexico,[39] then-President Andrew Jackson delayed recognizing the new republic until the last day of his presidency to avoid raising the issue during the 1836 general election.[40][41] Jackson's political caution was dictated by northern concerns that Texas could potentially form several new slave states and undermine the North-South balance in Congress.[42]

Jackson's successor, President Martin Van Buren, viewed Texas annexation as an immense political liability that would empower the anti-slavery northern Whig opposition – especially if annexation provoked a war with Mexico.[43] Presented with a formal annexation proposal from Texas minister Memucan Hunt Jr. in August 1837, Van Buren summarily rejected it.[44] Annexation resolutions presented separately in each house of Congress were either soundly defeated or tabled through filibuster. In 1838, Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar withdrew his republic's offer of annexation over these failures.[45] Texians were at an annexation impasse when John Tyler entered the White House in 1841.[46]

William Henry Harrison, Whig Party presidential nominee, defeated US President Martin Van Buren in the 1840 general election. Upon Harrison's death shortly after his inauguration, Vice-President John Tyler assumed the presidency.[47] President Tyler was expelled from the Whig party in 1841 for repeatedly vetoing their domestic finance legislation. Tyler, isolated and outside the two-party mainstream, turned to foreign affairs to salvage his presidency, aligning himself with a southern states' rights faction that shared his fervent slavery expansionist views.[48]

In his first address to Congress in special session on June 1, 1841, Tyler set the stage for Texas annexation by announcing his intention to pursue an expansionist agenda so as to preserve the balance between state and national authority and to protect American institutions, including slavery, so as to avoid sectional conflict.[49] Tyler's closest advisors counseled him that obtaining Texas would assure him a second term in the White House,[50] and it became a deeply personal obsession for the president, who viewed the acquisition of Texas as the "primary objective of his administration".[51] Tyler delayed direct action on Texas to work closely with his Secretary of State Daniel Webster on other pressing diplomatic initiatives.[52]

With the Webster–Ashburton Treaty ratified in 1843, Tyler was ready to make the annexation of Texas his "top priority".[53] Representative Thomas W. Gilmer of Virginia was authorized by the administration to make the case for annexation to the American electorate. In a widely circulated open letter, understood as an announcement of the executive branch's designs for Texas, Gilmer described Texas as a panacea for North-South conflict and an economic boon to all commercial interests. The slavery issue, however divisive, would be left for the states to decide as per the US Constitution. Domestic tranquility and national security, Tyler argued, would result from an annexed Texas; a Texas left outside American jurisdiction would imperil the Union.[54] Tyler adroitly arranged the resignation of his anti-annexation Secretary of State Daniel Webster, and on June 23, 1843 appointed Abel P. Upshur, a Virginia states' rights champion and ardent proponent of Texas annexation. This cabinet shift signaled Tyler's intent to pursue Texas annexation aggressively.[55]

In late September 1843, in an effort to cultivate public support for Texas, Secretary Upshur dispatched a letter to the US Minister to Great Britain, Edward Everett, conveying his displeasure with Britain's global anti-slavery posture, and warning their government that forays into Texas's affairs would be regarded as "tantamount to direct interference 'with the established institutions of the United States'".[56] In a breach of diplomatic norms, Upshur leaked the communique to the press to inflame popular Anglophobic sentiments among American citizens.[57]

In the spring of 1843, the Tyler administration had sent executive agent Duff Green to Europe to gather intelligence and arrange territorial treaty talks with Great Britain regarding Oregon; he also worked with American minister to France, Lewis Cass, to thwart efforts by major European powers to suppress the maritime slave trade.[58] Green reported to Secretary Upshur in July 1843 that he had discovered a "loan plot" by American abolitionists, in league with Lord Aberdeen, British Foreign Secretary, to provide f