The megas doux (Greek: μέγας δούξ, pronounced [ˈmeɣaz ˈðuks], "grand duke") was one of the highest positions in the hierarchy of the later Byzantine Empire, denoting the commander-in-chief of the Byzantine navy. It is sometimes also given in English by the half-Latinizations megaduke or megadux.[1] The Greek word δούξ is the Hellenized form of the Latin term dux, meaning leader or commander.

The office was initially created by Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118), who reformed the derelict Byzantine navy and amalgamated the remnants of its various provincial squadrons into a unified force under the megas doux.[1] The Emperor's brother-in-law John Doukas is usually considered to have been the first to hold the title, being raised to it in 1092, when he was tasked with suppressing the Turkish emir Tzachas. There is however a document dated to December 1085, where a monk Niketas signs as supervisor of the estates of an unnamed megas doux.[2][3] The office of "doux [commander] of the fleet" (δούξ τοῦ στόλου, doux tou stolou), with similar responsibilities and hence perhaps a precursor of the office of megas doux, is also mentioned at the time, being given c. 1086 to Manuel Boutoumites and in 1090 to Constantine Dalassenos.[1][4]

Initially, the office may have designated ad hoc commanders-in-chief placed in charge of combined naval and land expeditions, before coming to denote the head of the imperial fleet.[5] John Doukas, the first known megas doux, led campaigns on both land and sea and was responsible for the re-establishment of firm Byzantine control over the Aegean and the islands of Crete and Cyprus in the years 1092–93 and over western Anatolia in 1097.[6][7][8] From this time the megas doux was also given overall control of the provinces of Hellas, the Peloponnese and Crete, which chiefly provided the manpower and resources for the fleet.[9][10] However, since the megas doux was one of the Empire's senior officials, and mostly involved with the central government and various military campaigns, de factο governance of these provinces rested with the provinces' praitor or katepano, and various local leaders.[11] During the 12th century, the post of megas doux was dominated by the Kontostephanos family;[1] one of its members, Andronikos Kontostephanos, was one of the most important officers of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180), assisting him in achieving many land and naval victories.

With the virtual disappearance of the Byzantine fleet after the Fourth Crusade, the title was retained as an honorific in the Empire of Nicaea. Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259–1282) assumed the title when he became regent for John IV Laskaris (r. 1258–1261), before being raised to senior co-emperor.[12] It was also used by the Latin Empire, where, in c. 1207, the Latin emperor awarded the island of Lemnos and the hereditary title of megadux to the Venetian (or possibly of mixed Greek and Venetian descent) Filocalo Navigajoso ("imperiali privilegio Imperii Megaducha est effectus").[1][13] His descendants inherited the title and the rule of Lemnos until evicted by the Byzantines in 1278.

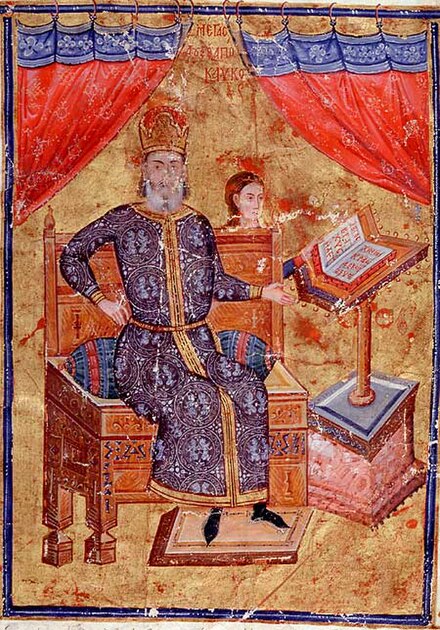

After the Byzantine recovery of Constantinople in 1261, the title reverted to its old function as commander-in-chief of the navy, and remained a high rank for the remainder of the empire, its holder ranking sixth after the emperor, between the protovestiarios and the protostrator.[1][14] As such, it was also sometimes conferred upon foreigners in imperial service, the most notable among these being the Italian Licario, who recovered many Aegean islands for Emperor Michael VIII,[15] and Roger de Flor, head of the Catalan Company.[1] The mid-14th century Book of Offices of Pseudo-Kodinos lists the insignia of the megas doux as a golden-red skiadion hat decorated with embroideries in the klapoton style, without veil. Alternatively, a domed skaranikon hat could be worn, again in red and gold and decorated with golden wire, with a portrait of the emperor standing in front, and another of him enthroned in the rear. The megas doux also wore a rich silk tunic, the kabbadion, and could choose the fabric himself "from those that are in use". His staff of office (dikanikion) featured carved knots and knobs in gold, bordered with silver braid.[16] Pseudo-Kodinos also records that, while the other warships flew "the usual imperial flag" of the cross and the firesteels, the flagship of the megas doux flew an image of the emperor on horseback.[17] His subordinate officials were the megas droungarios tou stolou, the ameralios, the protokomes, a number of junior droungarioi, and of junior kometes.[17]

The Serbian Empire, established in 1346 by Tsar Stefan Dushan, adopted various Byzantine titles, among them that of megas doux, which became the "grand voivode" (veliki vojvoda), albeit without any naval connotations. Holders of the office included senior noblemen such as Jovan Uglješa[18] and Jovan Oliver.[19]

In the 1490 Valencian epic romance Tirant lo Blanc, the valiant knight Tirant the White from Brittany travels to Constantinople and becomes a Byzantine megadux. This story has no basis in actual history, though it may reflect the above-mentioned cases of the office being conferred upon foreigners.