The origins of the American Civil War are rooted in the desire of the Southern states to preserve the institution of slavery.[1] Historians in the 21st century overwhelmingly agree on the centrality of slavery in the conflict. They disagree on which aspects (ideological, economic, political, or social) were most important, and on the North's reasons for refusing to allow the Southern states to secede.[2] The pseudo-historical Lost Cause ideology denies that slavery was the principal cause of the secession, a view disproven by historical evidence, notably some of the seceding states' own secession documents.[3] After leaving the Union, Mississippi issued a declaration stating, "Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world."[4][5]

The principal political battle leading to Southern secession was over whether slavery would expand into the Western territories destined to become states. Initially Congress had admitted new states into the Union in pairs, one slave and one free. This had kept a sectional balance in the Senate but not in the House of Representatives, as free states outstripped slave states in numbers of eligible voters.[6] Thus, at mid-19th century, the free-versus-slave status of the new territories was a critical issue, both for the North, where anti-slavery sentiment had grown, and for the South, where the fear of slavery's abolition had grown. Another factor leading to secession and the formation of the Confederacy was the development of white Southern nationalism in the preceding decades.[7] The primary reason for the North to reject secession was to preserve the Union, a cause based on American nationalism.[8]

Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election. His victory triggered declarations of secession by seven slave states of the Deep South, all of whose riverfront or coastal economies were based on cotton that was cultivated by slave labor. They formed the Confederate States of America after Lincoln was elected in November 1860 but before he took office in March 1861. Nationalists in the North and "Unionists" in the South refused to accept the declarations of secession. No foreign government ever recognized the Confederacy. The U.S. government, under President James Buchanan, refused to relinquish its forts that were in territory claimed by the Confederacy. The war itself began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces bombarded the Union's Fort Sumter, in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina.

Background factors in the run up to the Civil War were partisan politics, abolitionism, nullification versus secession, Southern and Northern nationalism, expansionism, economics, and modernization in the antebellum period. As a panel of historians emphasized in 2011, "while slavery and its various and multifaceted discontents were the primary cause of disunion, it was disunion itself that sparked the war."[9]

By the mid-19th century the United States had become a nation of two distinct regions. The free states in New England, the Northeast, and the Midwest[10] had a rapidly growing economy based on family farms, industry, mining, commerce, and transportation, with a large and rapidly growing urban population. Their growth was fed by a high birth rate and large numbers of European immigrants, especially from Ireland and Germany. The South was dominated by a settled plantation system based on slavery; there was some rapid growth taking place in the Southwest (e.g., Texas), based on high birth rates and high migration from the Southeast; there was also immigration by Europeans, but in much smaller number. The heavily rural South had few cities of any size, and little manufacturing except in border areas such as St. Louis and Baltimore. Slave owners controlled politics and the economy, although about 75% of white Southern families owned no slaves.[11]

Overall, the Northern population was growing much more quickly than the Southern population, which made it increasingly difficult for the South to dominate the national government. By the time the 1860 election occurred, the heavily agricultural Southern states as a group had fewer Electoral College votes than the rapidly industrializing Northern states. Abraham Lincoln was able to win the 1860 presidential election without even being on the ballot in ten Southern states. Southerners felt a loss of federal concern for Southern pro-slavery political demands, and their continued domination of the federal government was threatened. This political calculus provided a very real basis for Southerners' worry about the relative political decline of their region, due to the North growing much faster in terms of population and industrial output.

In the interest of maintaining unity, politicians had mostly moderated opposition to slavery, resulting in numerous compromises such as the Missouri Compromise of 1820 under the presidency of James Monroe. After the Mexican–American War of 1846 to 1848, the issue of slavery in the new territories led to the Compromise of 1850. While the compromise averted an immediate political crisis, it did not permanently resolve the issue of the Slave Power (the power of slaveholders to control the national government on the slavery issue). Part of the Compromise of 1850 was the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required Northerners to assist Southerners in reclaiming fugitive slaves, which many Northerners found to be extremely offensive.

Amid the emergence of increasingly virulent and hostile sectional ideologies in national politics, the collapse of the old Second Party System in the 1850s hampered politicians' efforts to reach yet another compromise. The compromise that was reached (the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act) outraged many Northerners and led to the formation of the Republican Party, the first major party that was almost entirely Northern-based. The industrializing North and agrarian Midwest became committed to the economic ethos of free-labor industrial capitalism.

Arguments that slavery was undesirable for the nation had long existed, and early in U.S. history were made even by some prominent Southerners. After 1840, abolitionists denounced slavery as not only a social evil but also a moral wrong. Activists in the new Republican Party, usually Northerners, had another view: They believed the Slave Power conspiracy was controlling the national government with the goal of extending slavery and limiting access to good farm land to rich slave owners.[12][13] Southern defenders of slavery, for their part, increasingly came to contend that black people benefited from slavery.

At the time of the American Revolution, the institution of slavery was firmly established in the American colonies. It was most important in the six southern states from Maryland to Georgia, but the total of a half million slaves were spread out through all of the colonies. In the South, 40 percent of the population was made up of slaves, and as Americans moved into Kentucky and the rest of the southwest, one-sixth of the settlers were slaves. By the end of the Revolutionary War, the New England states provided most of the American ships that were used in the foreign slave trade, while most of their customers were in Georgia and the Carolinas.[14]

During this time many Americans found it easy to reconcile slavery with the Bible, but a growing number rejected this defense of slavery. A small antislavery movement, led by the Quakers, appeared in the 1780s, and by the late 1780s all of the states had banned the international slave trade.[citation needed] No serious national political movement against slavery developed, largely due to the overriding concern over achieving national unity.[15] When the Constitutional Convention met, slavery was the one issue "that left the least possibility of compromise, the one that would most pit morality against pragmatism."[16] In the end, many would take comfort in the fact that the word "slavery" never occurs in the Constitution. The three-fifths clause was a compromise between those (in the North) who wanted no slaves counted, and those (in the South) who wanted all the slaves counted. The Constitution (Article IV, section 4) also allowed the federal government to suppress domestic violence, a provision that could be used against slave revolts. Congress could not ban the importation of slaves for 20 years. The need for the approval of three-fourths of the states for amendments made the constitutional abolition of slavery virtually impossible.[17]

The importation of slaves into the United States was restricted in 1794, and finally banned in 1808, the earliest date the Constitution permitted (Article 1, section 9). Many Americans believed that the passage of these laws had finally resolved the issue of slavery in the United States.[18] Any national discussion that might have continued over slavery was drowned out by other issues such as trade embargoes, maritime competition with Great Britain and France, the Barbary Wars, and the War of 1812. A notable exception to this quiet regarding slavery was the New Englanders' association of their frustration with the war with their resentment of the three-fifths clause that seemed to allow the South to dominate national politics.[19]

During the aftermath of the American Revolution (1775–1783), the Northern states (north of the Mason–Dixon line separating Maryland from Pennsylvania and Delaware) abolished slavery by 1804, although in some states older slaves were turned into indentured servants who could not be bought or sold. In the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Congress (at that time under the Articles of Confederation) barred slavery from the Midwestern territory north of the Ohio River.[20] When Congress organized the territories acquired through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, there was no ban on slavery.[21]

With the admission of Alabama as a slave state in 1819, the U.S. was equally divided, with 11 slave states and 11 free states. Later that year, Congressman James Tallmadge Jr. of New York initiated an uproar in the South when he proposed two amendments to a bill admitting Missouri to the Union as a free state. The first would have barred slaves from being moved to Missouri, and the second would have freed at age 25 all Missouri slaves born after admission to the Union.[22] The admission of the new state of Missouri as a slave state would give the slave states a majority in the Senate, while passage of the Tallmadge Amendment would give the free states a majority.

The Tallmadge amendments passed the House of Representatives but failed in the Senate when five Northern senators voted with all the Southern senators.[23] The question was now the admission of Missouri as a slave state, and many leaders shared Thomas Jefferson's fear of a crisis over slavery – a fear that Jefferson described as "a fire bell in the night". The crisis was solved by the Missouri Compromise, in which Massachusetts agreed to cede control over its relatively large, sparsely populated and disputed exclave, the District of Maine. The compromise allowed Maine to be admitted to the Union as a free state at the same time that Missouri was admitted as a slave state. The Compromise also banned slavery in the Louisiana Purchase territory north and west of the state of Missouri along parallel 36°30′ north. The Missouri Compromise quieted the issue until its limitations on slavery were repealed by the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854.[24]

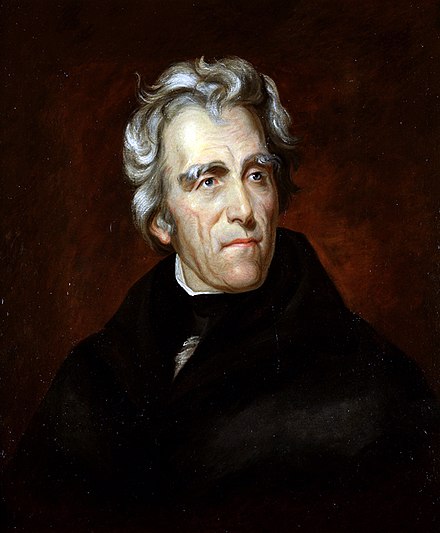

In the South, the Missouri crisis reawakened old fears that a strong federal government could be a fatal threat to slavery. The Jeffersonian coalition that united southern planters and northern farmers, mechanics and artisans in opposition to the threat presented by the Federalist Party had started to dissolve after the War of 1812.[25] It was not until the Missouri crisis that Americans became aware of the political possibilities of a sectional attack on slavery, and it was not until the mass politics of Andrew Jackson's administration that this type of organization around this issue became practical.[26]

The American System, advocated by Henry Clay in Congress and supported by many nationalist supporters of the War of 1812 such as John C. Calhoun, was a program for rapid economic modernization featuring protective tariffs, internal improvements at federal expense, and a national bank. The purpose was to develop American industry and international commerce. Since iron, coal, and water power were mainly in the North, this tax plan was doomed to cause rancor in the South, where economies were agriculture-based.[27][28] Southerners claimed it demonstrated favoritism toward the North.[29][30]