In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492. This era encompasses the history of Indigenous cultures prior to significant European influence, which in some cases did not occur until decades or even centuries after Columbus's arrival.

During the pre-Columbian era, many civilizations developed permanent settlements, cities, agricultural practices, civic and monumental architecture, major earthworks, and complex societal hierarchies. Some of these civilizations had declined by the time of the establishment of the first permanent European colonies, around the late 16th to early 17th centuries,[1] and are known primarily through archaeological research of the Americas and oral histories. Other civilizations, contemporaneous with the colonial period, were documented in European accounts of the time. For instance, the Maya civilization maintained written records, which were often destroyed by Christian Europeans such as Diego de Landa, who viewed them as pagan but sought to preserve native histories. Despite the destruction, a few original documents have survived, and others were transcribed or translated into Spanish, providing modern historians with valuable insights into ancient cultures and knowledge.

Before the development of archaeology in the 19th century, historians of the pre-Columbian period mainly interpreted the records of the European conquerors and the accounts of early European travelers and antiquaries. It was not until the nineteenth century that the work of people such as John Lloyd Stephens, Eduard Seler, and Alfred Maudslay, and institutions such as the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University, led to the reconsideration and criticism of the early European sources. Now, the scholarly study of pre-Columbian cultures is most often based on scientific and multidisciplinary methodologies.[2]

The haplogroup most commonly associated with Indigenous Amerindian genetics is Y-chromosome haplogroup Q1a3a.[3] Researchers have found genetic evidence that the Q1a3a haplogroup has been in South America since at least 18,000 BCE.[4] Y-chromosome DNA, like mtDNA, differs from other nuclear chromosomes in that the majority of the Y-chromosome is unique and does not recombine during meiosis. This has the effect that the historical pattern of mutations can easily be studied.[5] The pattern indicates Indigenous peoples of the Americas experienced two very distinctive genetic episodes: first with the initial peopling of the Americas and second with European colonization of the Americas.[6][7] The former is the determinant factor for the number of gene lineages and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous populations.[7]

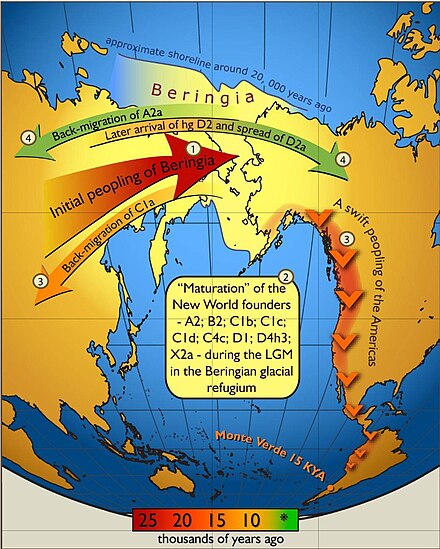

Human settlement of the Americas occurred in stages from the Bering Sea coastline, with an initial 20,000-year layover on Beringia for the founding population.[8][9] The microsatellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicate that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonization of the region.[10] The Na-Dené, Inuit, and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q-M242 (Y-DNA) mutations, however, and are distinct from other Indigenous peoples with various mtDNA mutations.[11][12][13] This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later populations.[14]

Asian nomadic Paleo-Indians are thought to have entered the Americas via the Bering Land Bridge (Beringia), now the Bering Strait, and possibly along the coast. Genetic evidence found in Indigenous peoples' maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) supports the theory of multiple genetic populations migrating from Asia.[15][16][17] After crossing the land bridge, they moved southward along the Pacific coast[18] and through an interior ice-free corridor.[19] Throughout millennia, Paleo-Indians spread throughout the rest of North and South America.

Exactly when the first people migrated into the Americas is the subject of much debate.[20] One of the earliest identifiable cultures was the Clovis culture, with sites dating from some 13,000 years ago.[21] However, older sites dating back to 20,000 years ago have been claimed. Some genetic studies estimate the colonization of the Americas dates from between 40,000 and 13,000 years ago.[22] The chronology of migration models is currently divided into two general approaches. The first is the short chronology theory with the first movement beyond Alaska into the Americas occurring no earlier than 14,000–17,000 years ago, followed by successive waves of immigrants.[23][24][25][26] The second belief is the long chronology theory, which proposes that the first group of people entered the hemisphere at a much earlier date, possibly 50,000–40,000 years ago or earlier.[27][28][29][30]

Artifacts have been found in both North and South America which have been dated to 14,000 years ago,[31] and accordingly humans have been proposed to have reached Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America by this time. In that case, the Inuit would have arrived separately and at a much later date, probably no more than 2,000 years ago, moving across the ice from Siberia into Alaska.

The North American climate was unstable as the ice age receded during the Lithic stage. It finally stabilized about 10,000 years ago; climatic conditions were then very similar to today's.[32] Within this time frame, roughly about the Archaic Period, numerous archaeological cultures have been identified.

The unstable climate led to widespread migration, with early Paleo-Indians soon spreading throughout the Americas, diversifying into many hundreds of culturally distinct tribes.[33] The Paleo-Indians were hunter-gatherers, likely characterized by small, mobile bands consisting of approximately 20 to 50 members of an extended family. These groups moved from place to place as preferred resources were depleted and new supplies were sought.[34] During much of the Paleo-Indian period, bands are thought to have subsisted primarily through hunting now-extinct giant land animals such as mastodon and ancient bison.[35] Paleo-Indian groups carried a variety of tools, including distinctive projectile points and knives, as well as less distinctive butchering and hide-scraping implements.

The vastness of the North American continent, and the variety of its climates, ecology, vegetation, fauna, and landforms, led ancient peoples to coalesce into many distinct linguistic and cultural groups.[36] This is reflected in the oral histories of the indigenous peoples, described by a wide range of traditional creation stories which often say that a given people have been living in a certain territory since the creation of the world.

Throughout thousands of years, paleo-Indian people domesticated, bred, and cultivated many plant species, including crops that now constitute 50–60% of worldwide agriculture.[37] In general, Arctic, Subarctic, and coastal peoples continued to live as hunters and gatherers, while agriculture was adopted in more temperate and sheltered regions, permitting a dramatic rise in population.[32]