The Maya civilization (/ˈmaɪə/) was a Mesoamerican civilization that existed from antiquity to the early modern period. It is known by its ancient temples and glyphs (script). The Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. The civilization is also noted for its art, architecture, mathematics, calendar, and astronomical system.

The Maya civilization developed in the Maya Region, an area that today comprises southeastern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador. It includes the northern lowlands of the Yucatán Peninsula and the Guatemalan Highlands of the Sierra Madre, the Mexican state of Chiapas, southern Guatemala, El Salvador, and the southern lowlands of the Pacific littoral plain. Today, their descendants, known collectively as the Maya, number well over 6 million individuals, speak more than twenty-eight surviving Mayan languages, and reside in nearly the same area as their ancestors.

The Archaic period, before 2000 BC, saw the first developments in agriculture and the earliest villages. The Preclassic period (c. 2000 BC to 250 AD) saw the establishment of the first complex societies in the Maya region, and the cultivation of the staple crops of the Maya diet, including maize, beans, squashes, and chili peppers. The first Maya cities developed around 750 BC, and by 500 BC these cities possessed monumental architecture, including large temples with elaborate stucco façades. Hieroglyphic writing was being used in the Maya region by the 3rd century BC. In the Late Preclassic, a number of large cities developed in the Petén Basin, and the city of Kaminaljuyu rose to prominence in the Guatemalan Highlands. Beginning around 250 AD, the Classic period is largely defined as when the Maya were raising sculpted monuments with Long Count dates. This period saw the Maya civilization develop many city-states linked by a complex trade network. In the Maya Lowlands two great rivals, the cities of Tikal and Calakmul, became powerful. The Classic period also saw the intrusive intervention of the central Mexican city of Teotihuacan in Maya dynastic politics. In the 9th century, there was a widespread political collapse in the central Maya region, resulting in civil wars, the abandonment of cities, and a northward shift of population. The Postclassic period saw the rise of Chichen Itza in the north, and the expansion of the aggressive Kʼicheʼ kingdom in the Guatemalan Highlands. In the 16th century, the Spanish Empire colonised the Mesoamerican region, and a lengthy series of campaigns saw the fall of Nojpetén, the last Maya city, in 1697.

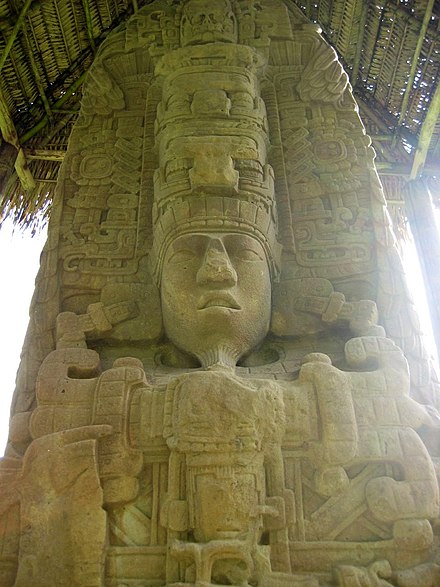

Rule during the Classic period centred on the concept of the "divine king", who was thought to act as a mediator between mortals and the supernatural realm. Kingship was usually (but not exclusively)[1] patrilineal, and power normally passed to the eldest son. A prospective king was expected to be a successful war leader as well as a ruler. Closed patronage systems were the dominant force in Maya politics, although how patronage affected the political makeup of a kingdom varied from city-state to city-state. By the Late Classic period, the aristocracy had grown in size, reducing the previously exclusive power of the king. The Maya developed sophisticated art forms using both perishable and non-perishable materials, including wood, jade, obsidian, ceramics, sculpted stone monuments, stucco, and finely painted murals.

Maya cities tended to expand organically. The city centers comprised ceremonial and administrative complexes, surrounded by an irregularly shaped sprawl of residential districts. Different parts of a city were often linked by causeways. Architecturally, city buildings included palaces, pyramid-temples, ceremonial ballcourts, and structures specially aligned for astronomical observation. The Maya elite were literate, and developed a complex system of hieroglyphic writing. Theirs was the most advanced writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. The Maya recorded their history and ritual knowledge in screenfold books, of which only three uncontested examples remain, the rest having been destroyed by the Spanish. In addition, a great many examples of Maya texts can be found on stelae and ceramics. The Maya developed a highly complex series of interlocking ritual calendars, and employed mathematics that included one of the earliest known instances of the explicit zero in human history. As a part of their religion, the Maya practised human sacrifice.

"Maya" is a modern term used to refer collectively to the various peoples that inhabited this area, as Maya peoples have not had a sense of a common ethnic identity or political unity for the vast majority of their history.[2] Early Spanish and Mayan-language colonial sources in the Yucatán Peninsula used the term "Maya" to denote both the language spoken by the Yucatec Maya and the area surrounding the then-abandoned city of Mayapán, from which the term derived. Some colonial Mayan-language sources also used "Maya" to refer to other Maya groups, sometimes pejoratively in reference to Maya groups more resistant to Spanish rule. [3]

The Maya civilization occupied a wide territory that included southeastern Mexico and northern Central America. This area included the entire Yucatán Peninsula and all of the territory now in the modern countries of Guatemala and Belize, as well as the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador.[4] Most of the peninsula is formed by a vast plain with few hills or mountains and a generally low coastline.[5] The territory of the Maya covered a third of Mesoamerica,[6] and the Maya were engaged in a dynamic relationship with neighbouring cultures that included the Olmecs, Mixtecs, Teotihuacan, and Aztecs.[7] During the Early Classic period, the Maya cities of Tikal and Kaminaljuyu were key Maya foci in a network that extended into the highlands of central Mexico;[8] there was a strong Maya presence at the Tetitla compound of Teotihuacan.[9] The Maya city of Chichen Itza and the distant Toltec capital of Tula had an especially close relationship.[10]

The Petén region consists of densely forested low-lying limestone plain;[11] a chain of fourteen lakes runs across the central drainage basin of Petén.[12] To the south the plain gradually rises towards the Guatemalan Highlands.[13] The dense Maya forest covers northern Petén and Belize, most of Quintana Roo, southern Campeche, and a portion of the south of Yucatán state. Farther north, the vegetation turns to lower forest consisting of dense scrub.[14]

The littoral zone of Soconusco lies to the south of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas,[15] and consists of a narrow coastal plain and the foothills of the Sierra Madre.[16] The Maya highlands extend eastwards from Chiapas into Guatemala, reaching their highest in the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes. Their major pre-Columbian population centres were in the largest highland valleys, such as the Valley of Guatemala and the Quetzaltenango Valley. In the southern highlands, a belt of volcanic cones runs parallel to the Pacific coast. The highlands extend northwards into Verapaz, and gradually descend to the east.[17]

The history of Maya civilization is divided into three principal periods: the Preclassic, Classic, and Postclassic.[18] These were preceded by the Archaic Period, during which the first settled villages and early developments in agriculture emerged.[19] Modern scholars regard these periods as arbitrary divisions of Maya chronology, rather than indicative of cultural evolution or decline.[20] Definitions of the start and end dates of period spans can vary by as much as a century, depending on the author.[21]

The Maya developed their first civilization in the Preclassic period.[25] Scholars continue to discuss when this era of Maya civilization began. Maya occupation at Cuello (modern Belize) has been carbon dated to around 2600 BC.[26] Settlements were established around 1800 BC in the Soconusco region of the Pacific coast, and the Maya were already cultivating the staple crops of maize, beans, squash, and chili pepper.[27] This period was characterised by sedentary communities and the introduction of pottery and fired clay figurines.[28]

During the Middle Preclassic Period, small villages began to grow to form cities.[29] Nakbe in the Petén department of Guatemala is the earliest well-documented city in the Maya lowlands,[30] where large structures have been dated to around 750 BC.[29] The northern lowlands of Yucatán were widely settled by the Middle Preclassic.[31] By approximately 400 BC, early Maya rulers were raising stelae.[32] A developed script was already being used in Petén by the 3rd century BC.[33] In the Late Preclassic Period, the enormous city of El Mirador grew to cover approximately 16 square kilometres (6.2 sq mi).[34] Although not as large, Tikal was already a significant city by around 350 BC.[35]

In the highlands, Kaminaljuyu emerged as a principal centre in the Late Preclassic.[36] Takalik Abaj and Chocolá were two of the most important cities on the Pacific coastal plain,[37] and Komchen grew to become an important site in northern Yucatán.[38] The Late Preclassic cultural florescence collapsed in the 1st century AD and many of the great Maya cities of the epoch were abandoned; the cause of this collapse is unknown.[39]

The Classic period is largely defined as the period during which the lowland Maya raised dated monuments using the Long Count calendar.[41] This period marked the peak of large-scale construction and urbanism, the recording of monumental inscriptions, and demonstrated significant intellectual and artistic development, particularly in the southern lowland regions.[41] The Classic period Maya political landscape has been likened to that of Renaissance Italy or Classical Greece, with multiple city-states engaged in a complex network of alliances and enmities.[42] The largest cities had 50,000 to 120,000 people and were linked to networks of subsidiary sites.[43]

During the Early Classic, cities throughout the Maya region were influenced by the great metropolis of Teotihuacan in the distant Valley of Mexico.[44] In AD 378, Teotihuacan decisively intervened at Tikal and other nearby cities, deposed their rulers, and installed a new Teotihuacan-backed dynasty.[45] This intervention was led by Siyaj Kʼakʼ ("Born of Fire"), who arrived at Tikal in early 378. The king of Tikal, Chak Tok Ichʼaak I, died on the same day, suggesting a violent takeover.[46] A year later, Siyaj Kʼakʼ oversaw the installation of a new king, Yax Nuun Ahiin I.[47] This led to a period of political dominance when Tikal became the most powerful city in the central lowlands.[47]

Tikal's great rival was Calakmul, another powerful city in the Petén Basin.[48] Tikal and Calakmul both developed extensive systems of allies and vassals; lesser cities that entered one of these networks gained prestige from their association with the top-tier city, and maintained peaceful relations with members of the network.[49] Tikal and Calakmul engaged in the manoeuvering of their alliance networks against each other. At various points during the