The Mesoamerican ballgame (Nahuatl languages: ōllamalīztli, Nahuatl pronunciation: [oːlːamaˈlistɬi], Mayan languages: pitz) was a sport with ritual associations played since at least 1650 BC[1] by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modernized version of the game, ulama, is still played by the indigenous populations in some places.[2]

The rules of the Mesoamerican ballgame are not known, but judging from its descendant, ulama, they were probably similar to racquetball,[3] where the aim is to keep the ball in play. The stone ballcourt goals are a late addition to the game.[citation needed]

In the most common theory of the game, the players struck the ball with their hips, although some versions allowed the use of forearms, rackets, bats, or handstones. The ball was made of solid rubber and weighed as much as 4 kg (9 lbs), and sizes differed greatly over time or according to the version played.

The Mesoamerican ballgame had important ritual aspects, and major formal ballgames were held as ritual events. Late in the history of the game, some cultures occasionally seem to have combined competitions with religious human sacrifice. The sport was also played casually for recreation by children and may have been played by women as well.[4]

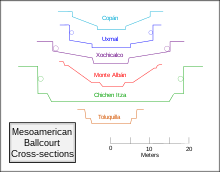

Pre-Columbian ballcourts have been found throughout Mesoamerica, as for example at Copán, as far south as modern Nicaragua, and possibly as far north as what is now the U.S. state of Arizona.[5] These ballcourts vary considerably in size, but all have long narrow alleys with slanted side-walls against which the balls could bounce.

The Mesoamerican ballgame is known by a wide variety of names. In English, it is often called pok-ta-pok (or pok-a-tok). This term originates from a 1932 article by Danish archaeologist Frans Blom, who adapted it from the Yucatec Maya word pokolpok.[6][7]

In Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, it was called ōllamaliztli ([oːlːamaˈlistɬi]) or tlachtli ([ˈtɬatʃtɬi]). In Classical Maya, it was known as pitz. In modern Spanish, it is called juego de pelota maya ('Maya ballgame'),[8] juego de pelota mesoamericano ('Mesoamerican ballgame'),[9] or simply pelota maya ('Maya ball').

It is not known precisely when or where the Mesoamerican ballgame originated, although it is likely that it originated earlier than 2000 BC in the low-lying tropical zones home to the rubber tree.[10]

One candidate for the birthplace of the ballgame is the Soconusco coastal lowlands along the Pacific Ocean.[11] Here, at Paso de la Amada, archaeologists have found the oldest ballcourt yet discovered, dated to approximately 1400 BC.[12]

The other major candidate is the Olmec heartland, across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec along the Gulf Coast.[13] The Aztecs referred to their Postclassic contemporaries who then inhabited the region as the Olmeca (i.e. "rubber people") since the region was strongly identified with latex production.[14] The earliest-known rubber balls in the world come from the sacrificial bog at El Manatí, an early Olmec-associated site located in the hinterland of the Coatzacoalcos River drainage system.[15]

Villagers, and archaeologists, have recovered a dozen balls ranging in diameter from 10 to 22 cm from the freshwater spring there. Five of these balls have been dated to the earliest-known occupational phase for the site, approximately 1700–1600 BC.[16] These rubber balls were found with other ritual offerings buried at the site, indicating that even at this early date the game had religious and ritual connotations.[17][18] A stone "yoke" of the type frequently associated with Mesoamerican ballcourts was also reported to have been found by local villagers at the site, leaving open the distinct possibility that these rubber balls were related to the ritual ballgame, and not simply an independent form of sacrificial offering.[19][20]

Excavations at the nearby Olmec site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán have also uncovered a number of ballplayer figurines, radiocarbon-dated as far back as 1250–1150 BC. A rudimentary ballcourt, dated to a later occupation at San Lorenzo, 600–400 BC, has also been identified.[21]

From the tropical lowlands, the game apparently moved into central Mexico. Starting around 1000 BC or earlier, ballplayer figurines were interred with burials at Tlatilco and similarly styled figurines from the same period have been found at the nearby Tlapacoya site.[22] It was about this period, as well, that the so-called Xochipala-style ballplayer figurines were crafted in Guerrero. Although no ballcourts of similar age have been found in Tlatilco or Tlapacoya, it is possible that the ballgame was indeed played in these areas, but on courts with perishable boundaries or temporary court markers.[23]

By 300 BC, evidence for the game appears throughout much of the Mesoamerican archaeological record, including ballcourts in the Central Chiapas Valley (the next oldest ballcourts discovered, after Paso de la Amada),[24] and in the Oaxaca Valley, as well as ceramic ballgame tableaus from Western Mexico (see photo below).

As might be expected with a game played over such a long period of time by many cultures, details varied over time and place, so the Mesoamerican ballgame might be more accurately seen as a family of related games.

In general, the hip-ball version is most popularly thought of as the Mesoamerican ballgame,[25] and researchers believe that this version was the primary—or perhaps only—version played within the masonry ballcourt.[26] Ample archaeological evidence exists for games where the ball was struck by a wooden stick (e.g., a mural at Teotihuacan shows a game which resembles field hockey), racquets, bats and batons, handstones, and the forearm, perhaps at times in combination. Each of the various types of games had its own size of ball, specialized gear and playing field, and rules.

Games were played between two teams of players. The number of players per team could vary, from two to four.[27][28] Some games were played on makeshift courts for simple recreation while others were formal spectacles on huge stone ballcourts leading to human sacrifice.

.jpg/440px-Ulama_37_(Aguilar).jpg)

Even without human sacrifice, the game could be brutal and there were often serious injuries inflicted by the solid, heavy ball. Today's hip-ulama players are "perpetually bruised"[29] while nearly 500 years ago Spanish chronicler Diego Durán reported that some bruises were so severe that they had to be lanced open. He also reported that players were even killed when the ball "hit them in the mouth or the stomach or the intestines".[30]

The rules of the Mesoamerican ballgame, regardless of the version, are not known in any detail. In modern-day ulama, the game resembles a netless volleyball,[31] with each team confined to one half of the court. In the most widespread version of ulama, the ball is hit back and forth using only the hips until one team fails to return it or the ball leaves the court.

In the Postclassic period, the Maya began placing vertical stone rings on each side of the court, the object being to pass the ball through one, an innovation that continued into the later Toltec and Aztec cultures.

In the 16th-century Aztec ballgame that the Spaniards witnessed, points were lost by a player who let the ball bounce more than twice before returning it to the other team, who let the ball go outside the boundaries of the court, or who tried and failed to pass the ball through one of the stone rings placed on each wall along the center line.[32] According to 16th-century Aztec chronicler Motolinia, points were gained if the ball hit the opposite end wall, while the decisive victory was reserved for the team that put the ball through a ring.[33] However, placing the ball through the ring was a rare event—the rings at Chichen Itza, for example, were set 6 metres (20 ft) off the playing field—and most games were likely won on points.[34]

The game's paraphernalia—clothing, headdresses, gloves, all but the stone—are long gone, so knowledge on clothing relies on art—paintings and drawings, stone reliefs, and figurines—to provide evidence for pre-Columbian ballplayer clothing and gear, which varied considerably in type and quantity. Capes and masks, for example, are shown on several Dainzú reliefs, while Teotihuacan murals show men playing stick-ball in skirts.[35]

The basic hip-game outfit consisted of a loincloth, sometimes augmented with leather hip guards. Loincloths are found on the earliest ballplayer figurines from Tlatilco, Tlapacoya, and the Olmec culture, are seen in the Weiditz drawing from 1528 (below), and, with hip guards, are the sole outfit of modern-day ulama players (above)—a span of nearly 3,000 years.

In many cultures, further protection was provided by a thick girdle, most likely of wicker or wood covered in fabric or leather. Made of perishable materials, none of these girdles have survived, although many stone "yokes" have been uncovered. Misnamed by earlier archaeologists due to its resemblance to an animal yoke, the stone yoke is thought to be too heavy for actual play and was likely used only before or after the game in ritual contexts.[36] In addition to providing some protection from the ball, the girdle or yoke would also have helped propel the ball with more force than the hip alone. Additionally, some players wore chest protectors called palmas which were inserted into the yoke and stood upright in front of the chest.

Kneepads are seen on a variety of players from many areas and eras and are worn by forearm-ulama players today. A type of garter is also often seen, worn just below the knee or around the ankle—it is not known what function this served. Gloves appear on the purported ballplayer reliefs of Dainzú, roughly 500 BC, as well as the Aztec players are drawn by Weiditz 2,000 years later (see drawing below).[37][30] Helmets, likely utilitarian, and elaborate headdresses, likely used only in ritual contexts, are common in ballplayer depictions. Headdresses are particularly prevalent on Maya painted vases or on Jaina Island figurines. Many ballplayers of the Classic era are seen with a right kneepad—no left—and a wrapped right forearm, as shown in the Maya image above.

The sizes or weights of the balls actually used in the ballgame are not known with any certainty. While several dozen ancient balls have been recovered, they were originally laid down as offerings in a sacrificial bog or spring, and there is no evidence that any of these were used in the ballgame. In fact, some of these extant votive balls were created specifically as offerings.[38]

However, based on a review of modern-day game balls, ancient rubber balls, and other archaeological evidence, it is presumed by most researchers that the ancient hip-ball was made of a mix from one or another of the latex-producing plants found all the way from the southeastern rain forests to the northern desert.[39] Most balls were made from latex sap of the lowland Castilla elastica tree. Someone discovered that by mixing latex with sap from the vine of a species of morning glory (Calonyction aculeatum) they could turn the slippery polymers in raw latex into a resilient rubber. The size varied between 10 and 12 in (25 and 30 cm) (measured in hand spans) and weighed 3 to 6 lb (1.4 to 2.7 kg).[40] The ball used in the ancient handball or stick-ball game was probably slightly larger and heavier than a modern-day baseball.[41][42]

Some Maya depictions, such as this relief, show balls 1 m (3 ft 3 in) or more in diameter. Academic consensus is that these depictions are exaggerations or symbolic, as are, for example, the impossibly unwieldy headdresses worn in the same portrayals.[43][44]

-shape ball court in Cihuatán site, El Salvador

-shape ball court in Cihuatán site, El Salvador

The game was played within a large masonry structure. Built in a form that changed remarkably little during 2,700 years, over 1,300 Mesoamerican ballcourts have been identified, 60% in the last 20 years alone.[45] All ballcourts have the same general shape, a long narrow playing alley flanked by walls with both horizontal and sloping (or, more rarely, vertical) surfaces. The walls were often plastered and brightly painted. In early ballcourts the alleys were open-ended; later ballcourts had enclosed end-zones, giving the structure an ![]() -shape when viewed from above.

-shape when viewed from above.

While the length-to-width ratio remained relatively constant at about four-to-one,[46] there was tremendous variation in ballcourt size: The playing field of the Great Ballcourt at Chichen Itza, by far the largest, measures 96.5 by 30 metres (317 by 98 ft), while the Ceremonial Court at Tikal was only 16 by 5 metres (52 by 16 ft).[47]

Across Mesoamerica, ballcourts were built and used for many generations. Although ballcourts are found within most sizable Mesoamerican ruins, they are not equally distributed across time or geography. For example, the Late Classic site of El Tajín, the largest city of the ballgame-obsessed Classic Veracruz culture, has at least 18 ballcourts, and Cantona, a nearby contemporaneous site, sets the record with 24.[48] In contrast, northern Chiapas[49] and the northern Maya Lowlands[50] have relatively few, and ballcourts are conspicuously absent at some major sites, including Teotihuacan, Bonampak, and Tortuguero, although Mesoamerican ballgame iconography has been found there.[51]

Ancient cities with particularly fine ballcourts in good condition include Tikal, Yaxha, Copán, Coba, Iximche, Monte Albán, Uxmal, Chichen Itza, Yagul, Xochicalco, Mixco Viejo, and Zaculeu.

Ballcourts were public spaces used for a variety of elite cultural events and ritual activities like musical performances and festivals, and, of course, the ballgame. Pictorial depictions often show musicians playing at ballgames, and votive deposits buried at the Main Ballcourt at Tenochtitlan contained miniature whistles, ocarinas, and drums. A pre-Columbian ceramic from western Mexico shows what appears to be a wrestling match taking place on a ballcourt.[52]