The change request management process in systems engineering is the process of requesting, determining attainability, planning, implementing, and evaluating of changes to a system. Its main goals are to support the processing and traceability of changes to an interconnected set of factors.[1]

There is considerable overlap and confusion between change request management, change control and configuration management. The definition below does not yet integrate these areas.

Change request management has been embraced for its ability to deliver benefits by improving the affected system and thereby satisfying "customer needs," but has also been criticized for its potential to confuse and needlessly complicate change administration. In some cases, notably in the Information Technology domain, more funds and work are put into system maintenance (and change request management) than into the initial creation of a system.[2] Typical investment by organizations during initial implementation of large ERP systems is 15 to 20 percent of overall budget.

In the same vein, Hinley [3] describes two of Lehman's laws of software evolution:

Change request management is also of great importance in the field of manufacturing, which is confronted with many changes due to increasing and worldwide competition, technological advances and demanding customers.[4] Because many systems tend to change and evolve as they are used, the problems of these industries are experienced to some degree in many others.

Notes: In the process below, it is arguable that the change committee should be responsible not only for accept/reject decisions, but also prioritization, which influences how change requests are batched for processing.

For the description of the change request management process, the meta-modeling technique is used. Figure 1 depicts the process-data diagram, which is explained in this section.

There are six main activities, which jointly form the change request management process. They are: Identify potential change, Analyze change request, Evaluate change, Plan change, Implement change and Review and close change. These activities are executed by four different roles, which are discussed in Table 1. The activities (or their sub-activities, if applicable) themselves are described in Table 2.

Besides activities, the process-data diagram (Figure 1) also shows the deliverables of each activity, i.e. the data. These deliverables or concepts are described in Table 3; in this context, the most important concepts are: CHANGE REQUEST and CHANGE LOG ENTRY.

A few concepts are defined by the author (i.e. lack a reference), because either no (good) definitions could be found, or they are the obvious result of an activity. These concepts are marked with an asterisk (‘*’). Properties of concepts have been left out of the model, because most of them are trivial and the diagram could otherwise quickly become too complex. Furthermore, some concepts (e.g. CHANGE REQUEST, SYSTEM RELEASE) lend themselves for the versioning approach as proposed by Weerd,[6] but this has also been left out due to diagram complexity constraints.

Besides just ‘changes’, one can also distinguish deviations and waivers.[7] A deviation is an authorization (or a request for it) to depart from a requirement of an item, prior to the creation of it. A waiver is essentially the same, but than during or after creation of the item. These two approaches can be viewed as minimalistic change request management (i.e. no real solution to the problem at hand).

A good example of the change request management process in action can be found in software development. Often users report bugs or desire new functionality from their software programs, which leads to a change request. The product software company then looks into the technical and economical feasibility of implementing this change and consequently it decides whether the change will actually be realized. If that indeed is the case, the change has to be planned, for example through the usage of function points. The actual execution of the change leads to the creation and/or alteration of software code and when this change is propagated it probably causes other code fragments to change as well. After the initial test results seem satisfactory, the documentation can be brought up to date and be released, together with the software. Finally, the project manager verifies the change and closes this entry in the change log.

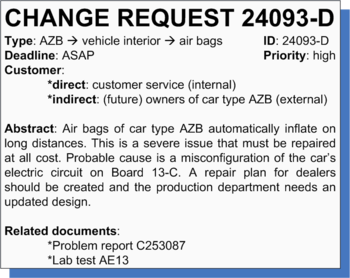

Another typical area for change request management in the way it is treated here, is the manufacturing domain. Take for instance the design and production of a car. If for example the vehicle's air bags are found to automatically fill with air after driving long distances, this will without a doubt lead to customer complaints (or hopefully problem reports during the testing phase). In turn, these produce a change request (see Figure 2 on the right), which will probably justify a change. Nevertheless, a – most likely simplistic – cost and benefit analysis has to be done, after which the change request can be approved. Following an analysis of the impact on the car design and production schedules, the planning for the implementation of the change can be created. According to this planning, the change can actually be realized, after which the new version of the car is hopefully thoroughly tested before it is released to the public.

Since complex processes can be very sensitive to even small changes, proper management of change to industrial process plants is recognized as critical to safety. Undocumented, not properly risk assessed changes are a recipe for disaster. An eminent example of this is the Flixborough explosion, where improvised changes involving the bypassing of a stage in a reactor train was at the origin of the accident. The change had not been properly thought out, documented and risk-assessed, so that the event of breach of containment had not been identified.[8] In the US, OSHA has regulations that govern how changes are to be made and documented. The main requirement is that a thorough review of a proposed change be performed by a multi-disciplinary team to ensure that as many possible viewpoints are used to minimize the chances of missing a hazard. In this context, change request management is known as Management of Change, or MOC. It is just one of many components of Process Safety Management, section 1910.119(l).1.