Мужской баскетбольный турнир NCAA Division I , известный как March Madness , — это турнир с выбыванием, который проводится в Соединенных Штатах для определения чемпиона мужского студенческого баскетбола уровня Division I в Национальной ассоциации студенческого спорта . Турнир проводится в основном в марте, в нем принимают участие 68 команд, и впервые он был проведен в 1939 году . Известный своими поражениями любимых команд, он стал одним из крупнейших ежегодных спортивных мероприятий в США.

Формат из 68 команд был принят в 2011 году ; он оставался практически неизменным с 1985 года , когда он был расширен до 64 команд. До этого размер турнира варьировался от 8 до 53. Поле было ограничено чемпионами конференции, пока в 1975 году не были расширены заявки на участие в целом , и команды не были полностью посеяны до 1979 года . В 2020 году турнир был впервые отменен из-за пандемии COVID-19 ; в следующем сезоне турнир был полностью разыгран в штате Индиана в качестве меры предосторожности.

На сегодняшний день турнир выиграли тридцать семь школ. Больше всего титулов у UCLA — 11 чемпионатов; их тренер Джон Вуден — самый титулованный тренер среди всех тренеров — 10. Университет Кентукки (Великобритания) выиграл восемь чемпионатов, Университет Коннектикута (UConn) и Университет Северной Каролины — по шесть чемпионатов, Университет Дьюка и Университет Индианы — по пять чемпионатов, Университет Канзаса (KU) — по четыре чемпионата, а Университет Вилланова — по три чемпионата. Семь программ разделили два национальных чемпионата, а 23 команды выиграли национальный чемпионат один раз.

Все игры турнира транслируются CBS , TBS , TNT и truTV под названием программы NCAA March Madness . По контракту до 2032 года Paramount Global и Warner Bros. Discovery ежегодно платят 891 миллион долларов за права на трансляцию. NCAA распределяет доходы между участвующими командами в зависимости от того, насколько далеко они продвинулись, что обеспечивает значительное финансирование студенческой атлетики. Турнир стал частью американской популярной культуры благодаря конкурсам по турнирной сетке, в которых за правильное предсказание результатов большинства игр присуждаются деньги и другие призы. В 2023 году Sports Illustrated сообщил, что, по оценкам, каждый год заполняется от 60 до 100 миллионов турнирных сеток.

Первый турнир был проведён в 1939 году и был выигран Орегоном . Это была идея тренера штата Огайо Гарольда Олсена . Национальная ассоциация баскетбольных тренеров провела первый турнир для NCAA.

С 1939 по 1950 год турнир NCAA состоял из восьми команд, каждая из которых выбиралась из географического округа. Несколько конференций считались частью каждого округа, например, конференции Missouri Valley и Big Seven в одном округе и Southern и Southeastern в другом, что часто приводило к тому, что команды с самым высоким рейтингом не участвовали в турнире. Проблема достигла апогея в 1950 году , когда NCAA предложила, чтобы третий по рейтингу Кентукки и пятый по рейтингу Северный Каролинский государственный университет соревновались в игре плей-офф за заявку, но Кентукки отказалась, посчитав, что им следует дать заявку как команде с более высоким рейтингом. В ответ NCAA удвоила поле до 16 в 1951 году , добавив два дополнительных округа и шесть мест для команд at-large. Конференции по-прежнему могли иметь только одну команду в турнире, но несколько конференций из одного географического округа теперь могли быть включены через заявки at-large. Это развитие помогло NCAA конкурировать с Национальным пригласительным турниром за престиж. [2]

В формате восьми команд турнир был разделен на Восточный и Западный регионы, а чемпионы встречались в игре национального чемпионата. Первые два раунда для каждого региона проводились на том же месте, что и национальный чемпионат, а с 1946 года утешительная игра проводилась неделю спустя. В некоторые годы местом проведения национального чемпионата было то же место, что и регионального чемпионата, а в другие годы — новое место. С расширением до 16 команд турнир сохранил первоначальный формат национальных полуфиналов, ставших региональными финалами в 1951 году . Для турнира 1952 года было четыре региона, названные Восток-1, Восток-2, Запад-1, Запад-2, все играли на отдельных площадках. Региональные чемпионы встретились для национальных полуфиналов и чемпионата в отдельном месте неделю спустя, установив формат с двумя финальными раундами турнира (хотя название «Финал четырех» не будет использоваться в брендинге до 1980-х годов).

Турнир 1953 года расширился до 22 команд и был добавлен пятый раунд, при этом десять команд получили путевку в региональные полуфиналы. Количество команд колебалось от 22 до 25 команд в течение следующих двух десятилетий, но количество раундов оставалось прежним. Двойное наименование регионов сохранялось до 1956 года , когда регионы были названы Восток, Средний Запад, Запад и Дальний Запад. В 1957 году регионы были названы Восток, Средний Восток, Средний Запад и Запад, что сохранялось до 1985 года. Регионы были разбиты на пары в национальных полуфиналах на основе их географического положения, при этом два восточных региона встречались в одном полуфинале, а два западных региона встречались в другом полуфинале.

Начиная с 1946 года , общенациональная игра за третье место проводилась перед игрой чемпионата. Региональные игры за третье место проводились на Западе с 1939 года и на Востоке с 1941 года . Несмотря на расширение в 1951 году , по-прежнему было только два региона, каждый с игрой за третье место. В турнире 1952 года было четыре региона, каждый с игрой за третье место.

Эта эпоха турнира характеризовалась конкуренцией с Национальным пригласительным турниром . Основанный Ассоциацией баскетбольных журналистов Метрополитен за год до турнира NCAA, NIT проводился полностью в Нью-Йорке в Мэдисон-сквер-гарден. Поскольку Нью-Йорк был центром прессы в Соединенных Штатах, NIT часто получал больше освещения, чем турнир NCAA в первые годы. Кроме того, хорошие команды часто исключались из турнира NCAA, потому что каждая конференция могла иметь только одну заявку, а чемпионы конференции даже исключались из-за системы 8 округов до 1950 года. Команды часто соревновались в обоих турнирах в течение первого десятилетия, а Городской колледж Нью-Йорка выиграл и турнир NIT , и турнир NCAA в 1950 году. Вскоре после этого NCAA запретила командам участвовать в обоих турнирах.

Два основных изменения в течение начала 1970-х годов привели к тому, что NCAA стала выдающимся постсезонным турниром для студенческого баскетбола. Во-первых, NCAA добавила правило в 1971 году , которое запрещало командам, отклонившим приглашение на турнир NCAA, участвовать в других постсезонных турнирах. Это было в ответ на то, что занимающая восьмое место команда Marquette отклонила его приглашение в 1970 году и вместо этого приняла участие и выиграла NIT после того, как тренер Эл Макгуайр пожаловался на их региональное размещение. С тех пор турнир NCAA, несомненно, был главным, в нем участвовали чемпионы конференций и большинство команд с самым высоким рейтингом. [3] Во-вторых, NCAA разрешила нескольким командам на конференцию, начиная с 1975 года . Это было в ответ на то, что нескольким командам с высоким рейтингом было отказано в заявках в начале 1970-х годов. К ним относились Южная Каролина в 1970 году, которая была непобежденной в игре конференции, но проиграла в турнире ACC; второе место в рейтинге USC в 1971 году , которое было исключено, поскольку их конференция была представлена лидирующим UCLA ; и Мэриленд в 1974 году , который занял 3-е место, но проиграл финальную игру турнира ACC будущему национальному чемпиону North Carolina State . [ требуется ссылка ]

Чтобы разместить заявки на участие в крупных соревнованиях, турнир был расширен в 1975 году , включив 32 команды, что позволило второй команде представлять конференцию в дополнение к чемпиону конференции [4] и выбывшим из игры. В 1979 году турнир был расширен до 40 команд и добавлен шестой раунд; 24 команды получили пропуск во второй раунд. Еще восемь команд были добавлены в 1980 году , и только 16 команд получили пропуск, а ограничение на количество заявок на участие в крупных соревнованиях от конференции было снято. [4] В 1983 году был добавлен седьмой раунд с четырьмя играми play-in; дополнительная игра play-in была добавлена в 1984 году . Начиная с 1973 года региональные пары для национальных полуфиналов менялись ежегодно вместо того, чтобы всегда играть два восточных и два западных региона.

В эту эпоху также началось распределение, что добавило драматизма и обеспечило лучшим командам лучшие пути к Финалу четырех. В 1978 году команды были распределены по двум отдельным пулам на основе их метода квалификации. В каждом регионе было четыре команды, которые автоматически квалифицировались, получив рейтинг Q1–Q4, и четыре команды, получившие общую заявку, получив рейтинг L1–L4. В 1979 году все команды в каждом регионе были распределены с 1 по 10, независимо от их метода квалификации.

Национальные полуфиналы были перенесены на субботу, а чемпионат был перенесен на понедельник вечером в 1973 году , где они и остаются с тех пор. До этого чемпионат проводился в субботу, а полуфиналы — за два дня до этого.

В этот период игры за третье место были отменены, последняя региональная игра за третье место состоялась в 1975 году , а последняя национальная игра за третье место — в 1981 году .

В 1985 году турнир расширился до 64 команд, исключив все бай-ины и плей-ины. Впервые всем командам нужно было выиграть шесть игр, чтобы выиграть турнир. Это расширение привело к увеличению освещения в СМИ и популярности в американской культуре. До 2001 года первый и второй раунды проводились на двух площадках в каждом регионе. [ требуется цитата ]

В 1985 году регион Ближнего Востока был переименован в регион Юго-Востока. В 1997 году регион Юго-Востока стал регионом Юга. С 2004 по 2006 годы регионы были названы в честь городов, где они проводились, например региональный Финикс в 2004 году, региональный Чикаго в 2005 году и региональный Миннеаполис в 2006 году, но вернулись к традиционным географическим обозначениям, начиная с 2007 года . Для турнира 2011 года регион Юга был Юго-Восточным регионом, а регион Среднего Запада — Юго-Западным регионом; оба вернулись к своим предыдущим названиям в 2012 году. [ необходима цитата ]

Финал четырех 1996 года был последним, который проводился на площадке, построенной специально для баскетбола. С тех пор Финал четырех проводится исключительно на больших крытых футбольных стадионах.

Начиная с 2001 года , поле было расширено с 64 до 65 команд, добавив к турниру то, что неофициально называлось «игрой в начале» . Это было в ответ на создание конференции Mountain West в 1999 году. Первоначально победитель турнира Mountain West не получал автоматическую заявку, так как это исключало бы одну из заявок at-large. В качестве альтернативы исключению заявки at-large NCAA расширила турнир до 65 команд . Сеяные #64 и #65 были посеяны в региональной сетке как 16 сеяных, а затем сыграли игру первого раунда во вторник, предшествующую первым выходным турнира. Эта игра всегда проводилась на арене университета Дейтона в Дейтоне, штат Огайо.

Начиная с 2004 года , отборочная комиссия опубликовала общие рейтинги среди посевов № 1. На основе этих рейтингов регионы были объединены в пары таким образом, чтобы посев № 1 играл с посевом № 4 в национальном полуфинале, если обе команды войдут в Финал четырех. Это было сделано для того, чтобы предотвратить встречу двух лучших команд до финала, как это было принято в 1996 году , когда Кентукки играл с Массачусетсом в Финале четырех. Ранее региональные пары менялись ежегодно.

В 2010 году ходили слухи об увеличении размера турнира до 128 команд. 1 апреля 2010 года NCAA объявила, что рассматривает возможность расширения до 96 команд в 2011 году . Однако три недели спустя NCAA объявила о новом телевизионном контракте с CBS/Turner, который расширил поле до 68 команд вместо 96, начиная с 2011 года. Первая четверка была создана путем добавления трех игр play-in. [5] В двух из игр Первой четверки соревнуются 16 команд. Однако в двух других играх соревнуются последние заявки at-large. Посев для команд at-large будет определяться отборочной комиссией и колеблется в зависимости от истинного рейтинга посева команд. Объясняя причины такого формата, председатель отборочной комиссии Дэн Герреро сказал: «Мы чувствовали, что если мы собираемся расширить поле, то это создаст лучшую драматичность для турнира, если Первая четверка будет намного более захватывающей. Они все могут быть на 10-й линии, на 12-й линии или на 11-й линии». [5] В рамках этого расширения раунд 64 был переименован во Второй раунд, а раунд 32 был переименован в Третий раунд, при этом Первая четверка официально стала Первым раундом. [5] В 2016 году раунды 64 и 32 вернулись к своим предыдущим названиям Первый раунд и Второй раунд, а Первая четверка стала официальным названием первого раунда. [6]

В 2016 году NCAA представила новый логотип «NCAA March Madness» для брендинга всего турнира, включая полностью брендированные площадки на каждом из мест проведения турнира. Ранее NCAA использовала существующую площадку или общую площадку NCAA.

Начиная с 2017 года , номер 1 в общем зачете выбирает площадки для своих игр первого и второго раунда и своих потенциальных региональных игр. Кроме того, отборочный комитет начал публиковать 16 лучших за три недели до Selection Sunday в качестве предварительного просмотра сетки.

Из-за пандемии COVID-19 NCAA отменила турнир 2020 года . Первоначально NCAA обсуждала проведение сокращенной версии с участием всего 16 команд в городе-хозяине Финала четырех Атланте. После того, как масштаб пандемии стал очевиден, NCAA отменила турнир, сделав его первым непроведенным изданием, и решила не публиковать таблицы, над которыми работал Отборочный комитет.

В 2021 году турнир проводился полностью в штате Индиана, чтобы сократить поездки. На сегодняшний день это был единственный раз, когда турнир проводился в одном штате. В качестве меры предосторожности от COVID-19 все участвующие команды должны были оставаться в предоставленных NCAA местах размещения до тех пор, пока они не проиграют. Расписание было скорректировано, чтобы предоставить больше времени для оценки COVID-19 до начала турнира, при этом Первая четверка полностью проводилась в четверг, Первый и Второй раунды были перенесены на один день назад на окно с пятницы по понедельник, а Сладкая шестнадцать и Элитная восьмерка также были перенесены на окно с пятницы по понедельник. Команды, занявшие 69–72 места Комитетом по отбору, были переведены в «резерв» для замены любой команды, которая снялась с турнира из-за протоколов COVID-19 в течение 48 часов после объявления турнирной сетки. Только одна игра была объявлена несостоявшейся из-за COVID-19, при этом Орегон перешел во второй раунд, потому что VCU не мог участвовать из-за протоколов COVID-19. VCU не был заменен одной из первых четырех команд, поскольку инфекции COVID-19 начались более чем через два дня после объявления сетки. Турнир вернулся к своему обычному формату в 2022 году .

В ответ на протесты игроков женского турнира 2021 года по поводу различного качества объектов и брендинга, как мужские , так и женские турниры были названы «NCAA March Madness» начиная с 2022 года с вариациями того же логотипа, который использовался на турнире среди мужчин. Кроме того, «Финал четырёх» для мужского турнира был назван «Мужской Финал четырёх» начиная с 2022 года, что отражает брендинг «Женский Финал четырёх», используемый для этого турнира с 1987 года .

.jpg/440px-1988_NCAA_Men's_Division_I_Basketball_Tournament_-_National_Semifinals_(ticket).jpg)

Турнир состоит из 68 команд, соревнующихся в семи раундах сетки с выбыванием после одного поражения . Тридцать две команды автоматически квалифицируются на турнир, выиграв свой конференц-турнир, сыгранный в течение двух недель перед турниром, и тридцать шесть команд квалифицируются, получив ставку at-large на основе их результатов в течение сезона. [8] Отборочный комитет определяет ставки at-large, ранжирует все команды от 1 до 68 и размещает команды в сетке, все это публично раскрывается в воскресенье перед турниром, которое СМИ и болельщики называют Selection Sunday . Во время турнира нет повторного посева, и матчи в каждом последующем раунде предопределены сеткой. [ необходима цитата ]

Турнир разделен на четыре региона, в каждом регионе от шестнадцати до восемнадцати команд. Регионы названы в честь географического района США, в котором проходит региональный полуфинал и региональный финал (третий и четвертый раунды турнира в целом). Города-хозяева для всех регионов меняются из года в год.

Турнир проводится в течение трех выходных, по два раунда в каждые выходные. Перед первыми выходными восемь команд соревнуются в первой четверке, чтобы пройти в первый раунд. Две игры объединяют чемпионов конференций с самым низким рейтингом, а две игры объединяют игроков, прошедших квалификацию at-large с самым низким рейтингом. Первый и второй раунды проводятся в первые выходные, региональные полуфиналы и региональные финалы — во вторые выходные, а национальные полуфиналы и игра за звание чемпиона — в третьи выходные. Региональные раунды называются Sweet Sixteen и Elite Eight, а третьи выходные — Final Four, все они названы в честь количества команд, оставшихся в начале раунда. Все игры, включая First Four, запланированы таким образом, чтобы у команд был один день отдыха между каждой игрой. Этот формат используется с 2011 года с небольшими изменениями в расписании в 2021 году из-за пандемии COVID-19 . [ необходима ссылка ]

Комитет по отбору, в который входят комиссары конференций и спортивные директора университетов , назначенные NCAA, определяет сетку в течение недели перед турниром. Поскольку результаты нескольких турниров конференций, проходящих в течение одной недели, могут существенно повлиять на сетку, Комитет часто делает несколько сеток для разных результатов.

Чтобы составить сетку, Комитет ранжирует все поле от 1 до 68; они называются истинным посевом . Затем Комитет делит команды между четырьмя регионами, давая каждой посев от № 1 до № 16. Те же четыре посева во всех регионах называются линией посева (т. е. линией посева № 6). Восемь команд объединяются и соревнуются в первой четверке. Две из парных команд соревнуются за посев № 16, а другие две парные команды являются последними командами, получившими заявки на участие в турнире, и соревнуются за линию посева в диапазоне от № 10 до № 14, который меняется из года в год в зависимости от истинных посевов команд в целом. [9]

Четыре лучших общих посева размещаются как посевы № 1 в каждом регионе. Регионы парами, так что если все посевы № 1 попадут в Финальную четверку, то истинный посев № 1 будет играть с № 4, а № 2 будет играть с № 3. Команды № 2 предпочтительно размещаются так, чтобы истинный посев № 5 не был в паре с истинным посевом № 1. Комитет обеспечивает конкурентный баланс среди четырех лучших посевов в каждом регионе, суммируя значения истинных посевов и сравнивая значения между регионами. Если есть значительное отклонение, некоторые команды будут перемещены между регионами, чтобы сбалансировать распределение истинных посевов. [9]

Если в конференции от двух до четырех команд в первых четырех посевах, они будут размещены в разных регионах. В противном случае команды из одной конференции размещаются так, чтобы избежать повторного матча перед региональным финалом, если они играли три или более раз в сезоне, региональным полуфиналом, если они играли дважды, или вторым раундом, если они играли один раз. Кроме того, комитету рекомендуется избегать повторных матчей из регулярного сезона и турнира прошлых лет в первой четверке. Наконец, комитет попытается гарантировать, что команда не будет перемещена из своего предпочтительного географического региона необычно много раз на основе ее места в предыдущих двух турнирах. Чтобы следовать этим правилам и предпочтениям, комитет может переместить команду из ее ожидаемой линии посева. Так, например, 40-я команда в общем рейтинге, изначально запланированная как 10-я посевная в определенном регионе, может вместо этого быть перемещена на 9-ю посевную позицию или перемещена на 11-ю посевную позицию. [9]

С 2012 года комитет публикует список настоящих сеяных команд с 1 по 68 после объявления сетки. [9] С 2017 года Комитет по отбору публикует список 16 лучших команд за три недели до отборочного воскресенья. Этот список не гарантирует ни одной команде заявку, поскольку Комитет переоценивает все команды при начале окончательного процесса отбора. [10]

Линия посева четырех команд, соревнующихся в первой четверке, менялась каждый год в зависимости от общего рейтинга команд в данной области. [9]

В мужском турнире все площадки номинально нейтральны; командам запрещено играть турнирные игры на своих домашних площадках во время первого, второго и регионального раундов. Согласно правилам NCAA, любая площадка, на которой команда проводит более трех игр регулярного сезона (не включая предсезонные или игры турнира конференции), считается «домашней площадкой». [9] Для Первой четверки и Финальной четверки запрет на домашнюю площадку не применяется, поскольку эти раунды проводятся только на одной площадке. Первая четверка регулярно принимается Dayton Flyers ; как таковая, команда соревновалась на своей домашней площадке в 2015 году . [11] Поскольку Финальная четверка проводится на крытых футбольных стадионах, маловероятно, что команда будет играть на своей домашней площадке в будущем. Последний раз это было возможно в 1996 году , когда принимала Continental Airlines Arena , домашняя площадка Seton Hall .

В первом и втором раундах восемь площадок принимают игры, по четыре в каждый день раунда. Каждая площадка принимает два набора из четырех команд, называемых «подами». Чтобы ограничить перемещения, команды размещаются в подах ближе к дому, если только правила посева не запрещают это. Поскольку в каждом поде есть 4 лучших посева, команды с самым высоким рейтингом обычно получают ближайшие площадки.

Возможные стручки при посеве:

* Освобожденный титул не включен

Всего с 1939 года в турнире NCAA приняли участие 333 команды. Поскольку NCAA не делилась на дивизионы до 1957 года , некоторые школы, которые участвовали в турнире, больше не входят в Дивизион I. Среди школ Дивизиона I 46 никогда не попадали в турнир, включая 11, которые не имеют права участвовать, поскольку они переходят в Дивизион I.

Ключ

Для каждого сезона, начиная с 1979 года, 4 команды, посеянные под номером 1, показаны с двойным подчеркиванием , а 12 команд, посеянных между номерами 2 и 4, показаны с пунктирным подчеркиванием .

Жирным шрифтом выделена активная текущая серия по состоянию на турнир 2024 года.

*Выступление Канзаса в 2018 году было отменено.

В качестве турнирного ритуала команда-победитель обрезает сетки в конце региональных чемпионатов, а также в конце национального чемпионата. Начиная со старших и двигаясь вниз по классам, игроки отрезают по одной нити от каждой сетки; главный тренер обрезает последнюю нить, соединяющую сетку с кольцом, забирая себе саму сетку. [12] Исключение из правила главного тренера обрезать последнюю нить произошло в 2013 году , когда главный тренер Луисвилля Рик Питино отдал эту честь Кевину Уэру , который получил катастрофическую травму ноги во время турнира. [13] Эта традиция приписывается Эверетту Кейсу , тренеру Университета Северной Каролины , который стоял на плечах своих игроков, чтобы совершить подвиг после того, как «Вулфпэк» выиграл турнир Южной конференции в 1947 году. [14] CBS, с 1987 года и ежегодно до 2015 года, в нечетные годы с 2017 года, и TBS, с 2016 года, в четные годы, завершают турнир песней « One Shining Moment », исполненной Лютером Вандроссом .

Так же, как Олимпиада награждает золотыми, серебряными и бронзовыми медалями за первое, второе и третье место соответственно, NCAA награждает национальных чемпионов позолоченным деревянным кубком национального чемпионата NCAA. Проигравший в игре за чемпионат получает посеребренный национальный кубок за второе место. С 2006 года все четыре команды Финала четырех получают покрытый бронзой кубок регионального чемпионата NCAA; до 2006 года только команды, не попавшие в финальную игру, получали покрытый бронзой кубок за выход в полуфинал.

Чемпионы также получают памятное золотое чемпионское кольцо , а остальные три команды «Финала четырёх» получают кольца «Финала четырёх».

Национальная ассоциация баскетбольных тренеров также вручает более сложный мраморный/хрустальный трофей победившей команде. По всей видимости, эта награда вручается за то, что команда заняла первое место в опросе NABC по итогам сезона, но это неизменно то же самое, что и победитель чемпионата NCAA. В 2005 году Siemens AG приобрела права на наименование трофея NABC, который теперь называется Siemens Trophy. Раньше трофей NABC вручался сразу после стандартного трофея чемпионата NCAA, но это вызвало некоторую путаницу. [15] С 2006 года трофей Siemens/NABC вручается отдельно на пресс-конференции на следующий день после игры. [16]

После вручения кубка чемпионата выбирается один игрок, которому затем вручается награда Самому выдающемуся игроку (которая почти всегда достается команде-чемпиону). Она не должна быть такой же, как награда Самому ценному игроку, хотя иногда ее неофициально так и называют.

Поскольку драфт НБА проходит всего через три месяца после турнира NCAA, руководители НБА должны решить, как выступления игроков в максимум семи играх, от первой четверки до игры за чемпионство, должны повлиять на их решения по драфту. Исследование 2012 года для Национального бюро экономических исследований изучает, как мартовский турнир влияет на поведение профессиональных команд на июньском драфте. Исследование основано на данных с 1997 по 2010 год, которые рассматривают, как выдающиеся игроки студенческих турниров выступили на уровне НБА. [17] [18]

Исследователи определили, что игрок, который превосходит свои средние показатели регулярного сезона или который находится в команде, которая выигрывает больше игр, чем предполагает ее посев, будет выбран выше, чем он мог бы быть выбран в противном случае. В то же время исследование показало, что профессиональные команды не принимают во внимание результаты студенческих турниров в той степени, в которой они должны были бы, поскольку успех на турнире коррелирует с элитными профессиональными достижениями, особенно успехами на высшем уровне. «Если уж на то пошло, команды НБА недооценивают сигнал, подаваемый неожиданным выступлением на турнире NCAA March Madness, как предиктор будущего успеха НБА». [17] [18]

С 2011 года NCAA заключила совместный контракт с CBS и Warner Bros. Discovery . Освещение турнира разделено между CBS, TNT , TBS и truTV . [19]

Спортивные трансляции от CBS, TBS и TNT ведутся на всех четырех сетях, при этом баскетбольные команды колледжей CBS дополняются командами NBA TNT , а студийные сегменты проходят в CBS Broadcast Center в Нью-Йорке и студиях TNT в Атланте . В нью-йоркских студийных шоу к Грегу Гамбелу и Кларку Келлоггу из CBS присоединяются Кенни Смит и Чарльз Баркли из Inside the NBA на TNT , в то время как Сет Дэвис и Джей Райт из CBS помогают Эрни Джонсону из Inside the NBA , а также Адаму Лефко и Кэндис Паркер из TNT во вторник вечером в репортажах NBA. В то время как трое из голосов TNT NBA, Кевин Харлан , Иэн Игл и Сперо Дедес, уже работают на CBS в других должностях, TNT также предоставляет аналитиков Стэна Ван Ганди , Джима Джексона , Гранта Хилла и Стива Смита , второстепенного комментатора Брайана Андерсона и репортеров Элли Лафорс и Лорен Шехади , последняя из освещения MLB на TBS , на CBS. В свою очередь, комментаторы CBS Брэд Несслер , Эндрю Каталон и Том Маккарти появляются в трансляциях сети WBD вместе с аналитиками Джимом Спанаркелем , Биллом Рафтери , Дэном Боннером , Стивом Лаппасом , Бренданом Хейвудом и Эйвери Джонсоном , а также репортерами Трейси Вольфсон , Эваном Уошберном , Эй Джей Россом и Джоном Ротштейном, а также аналитиком правил Джином Стераторе . Дикторы из других сетей, такие как Лиза Байингтон и Робби Хаммел из Fox (последний также работает на Peacock и Big Ten Network) , Дебби Антонелли из ESPN , Джейми Эрдаль из NFL Network и Энди Кац из NCAA.com также работают на CBS и TNT.

The most recent transaction in 2016 renews the contract through 2032 and provides for the nationwide broadcast each year of all games of the tournament. All First Four games air on truTV. A featured first- or second-round game in each time "window" is broadcast on CBS, while all other games are shown either on TBS, TNT or truTV. The regional semifinals, better known as the Sweet Sixteen, are split between CBS and TBS. CBS had the exclusive rights to the regional finals, also known as the Elite Eight, through 2014. That exclusivity extended to the entire Final Four as well, but after the 2013 tournament Turner Sports elected to exercise a contractual option for 2014 and 2015 giving TBS broadcast rights to the national semifinal matchups.[20] CBS kept its national championship game rights.[20]

Since 2015, CBS and TBS split coverage of the Elite Eight. Since 2016 CBS and TBS alternate coverage of the Final Four and national championship game, with TBS getting the final two rounds in even-numbered years, and CBS getting the games in odd-numbered years. March Madness On Demand would remain unchanged, although Turner was allowed to develop their own service.[21]

The CBS broadcast provides the NCAA with over $500 million annually, and makes up over 90% of the NCAA's annual revenue.[22] The revenues from the multibillion-dollar television contract are divided among the Division I basketball playing schools and conferences as follows:[23]

CBS has been the major partner of the NCAA in televising the tournament since 1982, but there have been many changes in coverage since the tournament was first broadcast in 1969.

From 1969 to 1981, the NCAA tournament aired on NBC, but not all games were televised. The early rounds, in particular, were not always seen on TV.

In 1982, CBS obtained broadcast television rights to the NCAA tournament.

In 1980, ESPN began showing the opening rounds of the tournament. This was the network's first contract signed with the NCAA for a major sport, and helped to establish ESPN's following among college basketball fans. ESPN showed six first-round games on Thursday and again on Friday, with CBS, from 1982 to 1990, then picking up a seventh game at 11:30 pm ET. Thus, 14 of 32 first-round games were televised. ESPN also re-ran games overnight. At the time, there was only one ESPN network, with no ability to split its signal regionally, so ESPN showed only the most competitive games. During the 1980s, the tournament's popularity on television soared.[citation needed]

However, ESPN became a victim of its own success, as CBS was awarded the rights to cover all games of the NCAA tournament, starting in 1991. Only with the introduction of the so-called "play-in" game (between the 64 seed and the 65 seed) in the 2000s, did ESPN get back in the game (and actually, the first time this "play-in" game was played in 2001, the game was aired on The Nashville Network, using CBS graphics and announcers, as both CBS and TNN were both owned by Viacom at the time.[27]

Through 2010, CBS broadcast the remaining 63 games of the NCAA tournament proper. Most areas saw only eight of 32 first-round games, seven of 16 second-round games, and four of eight regional semifinal games (out of the possible 56 games during these rounds; there would be some exceptions to this rule in the 2000s). Coverage preempted regular programming on the network, except during a 2-hour window from about 5 ET until 7 ET when the local affiliates could show programming. The CBS format resulted in far fewer hours of first-round coverage than under the old ESPN format but allowed the games to reach a much larger audience than ESPN was able to reach.[citation needed]

During this period of near-exclusivity by CBS, the network provided to its local affiliates three types of feeds from each venue: constant feed, swing feed, and flex feed. Constant feeds remained primarily on a given game, and were used primarily by stations with a clear local interest in a particular game. Despite its name, a constant feed occasionally veered away to other games for brief updates (as is typical in most American sports coverage), but coverage generally remained with the initial game. A swing feed tended to stay on games believed to be of natural interest to the locality, such as teams from local conferences, but may leave that game to go to other games that during their progress become close matches. On a flex feed, coverage bounced around from one venue to another, depending on action at the various games in progress. If one game was a blowout, coverage could switch to a more competitive game. A flex feed was provided when there were no games with a significant natural local interest for the stations carrying them, which allowed the flex game to be the best game in progress. Station feeds were planned in advance and stations had the option of requesting either constant or flex feed for various games.[citation needed]

In 1999, DirecTV began broadcasting all games otherwise not shown on local television with its Mega March Madness premium package. The DirecTV system used the subscriber's ZIP code to black out games which could be seen on broadcast television. Prior to that, all games were available on C-Band satellite and were picked up by sports bars.

In 2003, CBS struck a deal with Yahoo! to offer live streaming of the first three rounds of games under its Yahoo! Platinum service, for $16.95 a month.[28] In 2004, CBS began selling viewers access to March Madness On Demand, which provided games not otherwise shown on broadcast television; the service was free for AOL subscribers. In 2006, March Madness On Demand was made free, and continued to be so to online users through the 2011 tournament. For 2012, it once again became a pay service, with a single payment of $3.99 providing access to all 67 tournament games. In 2013, the service, now renamed March Madness Live, was again made free, but uses Turner's rights and infrastructure for TV Everywhere, which requires sign-in though the password of a customer's cable or satellite provider to watch games, both via PC/Mac and mobile devices. Those that do not have a cable or satellite service or one not participating in Turner's TV Everywhere are restricted to games carried on the CBS national feed and three hours (originally four) of other games without sign-in, or coverage via Westwood One's radio coverage. Effective with the 2018 tournament, the national semifinals and final are under TV Everywhere restrictions if they are aired by Turner networks; before then, those particular games were not subject to said restrictions.

In addition, CBS Sports Network (formerly CBS College Sports Network) had broadcast two "late early" games that would not otherwise be broadcast nationally. These were the second games in the daytime session in the Pacific Time Zone, to avoid starting games before 10 AM. These games are also available via March Madness Live and on CBS affiliates in the market areas of the team playing. In other markets, newscasts, local programming or preempted CBS morning programming are aired. CBSSN is scheduled to continue broadcasting the official pregame and postgame shows and press conferences from the teams involved, along with overnight replays.[29]

The Final Four has been broadcast in HDTV since 1999. From 2000 to 2004, only one first/second round site and one regional site were designated as HDTV sites. In 2005, all regional games were broadcast in HDTV, and four first and second round sites were designated for HDTV coverage. Local stations broadcasting in both digital and analog had the option of airing separate games on their HD and SD channels, to take advantage of the available high definition coverage. Beginning in 2007, all games in the tournament (including all first and second-round games) were available in high definition, and local stations were required to air the same game on both their analog and digital channels. However, due to satellite limitations, first round "constant" feeds were only available in standard definition.[30] Moreover, some digital television stations, such as WRAL-TV in Raleigh, North Carolina, choose not to participate in HDTV broadcasts of the first and second rounds and the regional semifinals, and used their available bandwidth to split their signal into digital subchannels to show all games going on simultaneously.[31] By 2008, upgrades at the CBS broadcast center allowed all feeds, flex and constant, to be in HD for the tournament.

As of 2011, ESPN International holds international broadcast rights to the tournament, distributing coverage to its co-owned networks and other broadcasters. ESPN produces the world feed for broadcasts of the Final Four and championship game, produced using ESPN College Basketball staff and commentators.[32][33][34][35]

The top ten programs in total NCAA victories:

*Vacated victories not included

Programs with ten or more appearances in the Final Four:

*Vacated appearances not included

Since 1979, the NCAA has seeded each region. Beginning in 2004, the Selection Committee announced the rankings among the 1 seeds, designating an overall #1 seed and pairing the regions so that the overall #1 seed would meet the #4 overall seed in the Final Four if both advanced. The overall rankings are denoted with the numbers in parentheses. The following teams received the top ranking in each region:

*Vacated

Bold denotes team also won tournament

Last updated through 2024 tournament.

*Vacated appearances not included (see #1 seeds by year and region)

Only once did all four No. 1 seeds make it to the Final Four:

Four times (including three since the field expanded to 64 teams) the Final Four has been without a No. 1 seed:

Since 1985, there have been 4 instances of three No. 1 seeds reaching the Final Four; 13 instances of two No. 1 seeds making it; and 14 instances of just one No. 1 seed reaching the Final Four. 2023 was the first Final Four without a 1, 2, or 3 seed.

There have been ten occasions (nine times since the field expanded to 64) that the championship game has been played between two No. 1 seeds:

Since 1985 there have been 18 instances of one No. 1 seed reaching the Championship Game (No. 1 seeds are 13–5 against other seeds in the title game) and 8 instances where no No. 1 seed made it to the title game.

Teams that entered the tournament ranked No. 1 in at least one of the AP, UPI, or USA Today polls and won the tournament:[36]

The record here refers to the record before the first game of the NCAA tournament.

The NCAA tournament has dramatically expanded since 1975, and since the expansion to 48 teams in 1980, no unbeaten team has failed to qualify. Since by definition, a team would have to win its conference tournament, and thus secure an automatic bid to the tournament, to be undefeated in a season, the only way a team could finish undefeated and not reach the tournament is if the team is banned from postseason play. As of 2021, no team banned from postseason play has finished undefeated since 1980. Other possibilities for an undefeated team to fail to qualify: the team is independent; the conference does not have an automatic bid; or the team is transitioning from a lower NCAA division or the NAIA, during which time it is barred from NCAA-sponsored postseason play in the NCAA tournament or NIT. No men's team from a transitional D-I member has been unbeaten after its conference tournament, but one such women's team has been—California Baptist in 2021. (CBU was able to play in the women's NIT, which has never been operated by the NCAA.)

Before 1980, there were occasions on which a team achieved perfection in the regular season, yet did not appear in the NCAA tournament.

Eight programs have repeated as national championships. UCLA is the only program to win more than 2 in a row, winning 7 straight from 1967 to 1973. These programs are:

There have been nine times in which the tournament did not include the reigning champion (the previous year's winner):

Mid-major teams—which are defined as teams from the America East Conference (America East), ASUN Conference (ASUN), Atlantic 10 (A-10), Big Sky Conference (Big Sky), Big South Conference (Big South), Big West Conference (Big West), Coastal Athletic Association (CAA), Conference USA (C-USA), Horizon League (Horizon), Ivy League (Ivy), Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference (MAAC), Mid-American Conference (MAC), Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference (MEAC), Missouri Valley Conference (MVC), Mountain West Conference (MW), Northeast Conference (NEC), Ohio Valley Conference (OVC), Patriot League (Patriot), Southern Conference (SoCon), Southland Conference (Southland), Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC), Summit League (Summit), Sun Belt Conference (Sun Belt), West Coast Conference (WCC), and the Western Athletic Conference (WAC)[40]—have experienced success in the tournament.

The last time, as of 2024, a mid-major team won the National Championship was 1990 when UNLV won with a 103–73 win over Duke, since UNLV was then a member of the Big West and since 1999 has been a member of the MW; the Big West was not then considered a power conference, nor is the MW today. However, during the tenure of UNLV's coach at the time, Jerry Tarkanian, the Runnin' Rebels were widely viewed as a major program despite their conference affiliation (a situation similar to that of Gonzaga since the first years of the 21st century). Additionally, the Big West received three bids in the 1990 tournament. The last time, as of 2024, an independent mid-major team won the national championship was 1977 when Marquette won 67–59 over North Carolina. However, Marquette was not considered a "mid-major" program at that time. The very term "mid-major" was not coined until 1977 and did not see wide use until the 1990s. More significantly, Marquette was one of several traditional basketball powers that were still NCAA Division I independents in the late 1970s. Also, Marquette has been a member of widely acknowledged "major" basketball conferences since 1991, and is currently in the undeniably major Big East Conference. The last time, as of 2024, a mid-major team from a small media market (defined as a market that is outside of the top 25 television markets in the United States in 2024) won the National Championship was arguably 1962 when Cincinnati, then in the MVC, won 71–59 over Ohio State of the Big Ten, since Cincinnati's TV market is listed 35th in the nation as of 2024. However, the MVC was generally seen in that day as a major basketball conference.

The last time the Final Four was composed, as of 2024, of at least 75% mid-major teams (3/4), i.e. excluding all present-day major conferences or their predecessors, was 1979, where Indiana State, then as now of the Missouri Valley Conference (which had lost several of its most prominent programs, among them Cincinnati, earlier in the decade); Penn, then as now in the Ivy League; and DePaul, then an independent, participated in the Final Four, only to see Indiana State lose to Michigan State. The last time, as of 2024, the Final Four has been composed of at least 50% mid-major teams (2/4) was 2023, when Florida Atlantic, of Conference USA, and San Diego State, of the Mountain West Conference, participated in the Final Four, only to see San Diego State lose to UConn. To date, as of 2024, no Final Four has been composed of 100% mid-major teams (4/4), therefore guaranteeing a mid-major team winning the national championship.

Arguably the tournament with the most mid-major success was the 1970 tournament, which had 63% representation of mid-major teams in the Sweet 16 (10/16), 75% representation in the Elite 8 (6/8), 75% representation in the Final 4 (3/4), and 50% representation in the national championship game (1/2). Jacksonville lost to UCLA in the National Championship, with New Mexico State defeating St. Bonaventure for third place.

This table shows the performance of mid-major teams from the Sweet Sixteen round to the national championship game from 1939—the tournament's first year—to 2024.

This table shows teams that saw success in the tournament from later defunct conferences, or were independents.

One conference listed, the Southwest Conference, was universally considered a major conference throughout its history. Of its final eight members, five moved to conferences typically considered "major" in basketball—three in the Big 12, one in the SEC, and one in The American. Another member that left during the SWC's last decade also moved to the SEC. The Metro Conference, which operated from 1975 to 1995, is not listed because it was considered a major basketball conference throughout its history. The, Louisville, which was a member for the league's entire existence, won both of its NCAA-recognized titles (1980, 1986) while in the Metro. It was one of the two leagues that merged to form the Conference USA. The other league involved in the merger, the Great Midwest Conference, was arguably a major conference; it was formed in 1990, with play starting in 1991, when several of the Metro's strongest basketball programs left that league.

Rick Pitino is the only coach to have officially taken three teams to the Final Four: Providence (1987), Kentucky (1993, 1996, 1997) and Louisville (2005, 2012).

There are 14 coaches who have officially coached two schools to the Final Four – Roy Williams, Eddie Sutton, Frank McGuire, Lon Kruger, Hugh Durham, Jack Gardner, Lute Olson, Gene Bartow, Forddy Anderson, Lee Rose, Bob Huggins, Lou Henson, Kelvin Sampson and Jim Larrañaga.

Point differentials, or margin of victory, can be viewed either by the championship game, or by a team's performance over the whole tournament.

30 points, by UNLV in 1990 (103–73, over Duke)

1 point, on six occasions

Eight times the championship game has been tied at the end of regulation. On one of those occasions (1957) the game went into double and then triple overtime.

Teams that played 6 games

Teams that played 5 games

Teams that played 4 games

Teams that played 3 games

Achieved 14 times by 10 schools

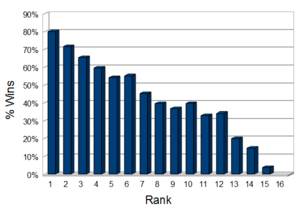

Since the inception of the 64-team tournament in 1985, each seed-pairing has played 156 games in the Round of 64, with the following results:

Until 1952, the national championship was played at a separate site from the national semifinal games, which were considered regional finals. Forty-one different venues have hosted the final rounds, and several have hosted more than five times:

Among cities, Kansas City has hosted the Final Four a total of ten times, with Kemper Arena hosting in 1988 in addition to Municipal Auditorium. New York and Indianapolis have both hosted seven times, with the latter doing so at three venues: Market Square Arena in 1980, four times in the RCA Dome between 1991 and 2006, and three times in Lucas Oil Stadium, between 2010 and 2021. The state of Texas has hosted the Final Four eleven times in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and Arlington between 1971 and 2023.

For most of the tournament's history, the national championship game and national semifinal games have been played in basketball arenas. The first instance of a domed stadium being used for the Final Four was the Houston Astrodome in 1971, but the Final Four would not return to a dome until 1982 when the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans hosted the event for the first time. The last on-campus venue to host the Final Four was University Arena in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1983. The last venue primarily built for a college basketball team to host the Final Four was Rupp Arena in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1985. The last NBA arena to host the Final Four was the Meadowlands Arena, then known as Continental Airlines Arena, in 1996. From 1997 to 2013, the NCAA required that the Final Four be played in domed stadiums with a minimum capacity of 40,000. As of 2009,[clarify] the minimum was increased to 70,000, by adding additional seating on the floor of the dome, and raising the court on a platform three feet above the dome's floor.

In September 2012, the NCAA began preliminary discussions on the possibility of returning occasional Final Fours to basketball-specific arenas in major metropolitan areas. According to ESPN.com writer Andy Katz, when Mark Lewis was hired as NCAA executive vice president for championships during 2012, "he took out a United States map and saw that both coasts are largely left off from hosting the Final Four."[43] Lewis added in an interview with Katz,

I don't know where this will lead, if anywhere, but the right thing is to sit down and have these conversations and see if we want our championship in more than eight cities or do we like playing exclusively in domes. None of the cities where we play our championship is named New York, Boston, Los Angeles, Chicago or Miami. We don't play on a campus. We play in professional football arenas.[43]

Under then-current criteria, only eleven stadiums could be considered as Final Four locations.[43] On June 12, 2013, Katz reported that the NCAA had changed its policy. In July 2013, the NCAA had a portal available on its website for venues to make Final Four proposals in the 2017–2020 period, and there were no restrictions on proposals based on venue size. Also, the NCAA decided that future regionals will no longer be held in domes. In Katz' report, Lewis indicated that the use of domes for regionals was intended as a dry run for future Final Four venues, but this particular policy was no longer necessary because all of the Final Four sites from 2014 to 2016 had already hosted regionals.[44] The policy was changed to only be used if a new venue would be hosting the subsequent tournament's Final Four.[45][46] Under the current policy, the 2030 regionals could be held at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, which opened in 2017 that will be hosting its first Final Four in 2031.

On several occasions NCAA tournament teams played their games in their home arena. In 1959, Louisville played at its regular home of Freedom Hall; however, the Cardinals lost to West Virginia in the semifinals. In 1984, Kentucky defeated Illinois, 54–51 in the Elite Eight on its home court of Rupp Arena. Also in 1984, #6 seeded Memphis played the first 2 rounds on its home court, defeating Oral Roberts and Purdue. In 1985, Dayton played its first-round game against Villanova (it lost 51–49) on its home floor. In 1986 (beating Brown before losing to Navy) and '87 (beating Georgia Southern and Western Kentucky), Syracuse played the first 2 rounds of the NCAA tournament in the Carrier Dome. Also in 1986, LSU played in Baton Rouge on its home floor for the first 2 rounds despite being an 11th seed (beating Purdue and Memphis State). In 1987, Arizona lost to UTEP on its home floor in the first round. In 2015, Dayton played at its regular home of UD Arena, and the Flyers beat Boise State in the First Four.

Since the inception of the modern Final Four in 1952, only once has a team played a Final Four on its actual home court—Louisville in 1959. But through the 2015 tournament, three other teams have played the Final Four in their home cities, one other team has played in its metropolitan area, and six additional teams have played the Final Four in their home states through the 2015 tournament. Kentucky (1958 in Louisville), UCLA (1968 and 1972 in Los Angeles, 1975 in San Diego), and North Carolina State (1974 in Greensboro) won the national title; Louisville (1959 at its home arena, Freedom Hall); Purdue (1980 in Indianapolis) lost in the Final Four; and California (1960 in the San Francisco Bay Area), Duke (1994 in Charlotte), Michigan State (2009 in Detroit), and Butler (2010 in Indianapolis) lost in the final.

In 1960, Cal had nearly as large an edge as Louisville had the previous year, only having to cross the San Francisco Bay to play in the Final Four at the Cow Palace in Daly City; the Golden Bears lost in the championship game to Ohio State. UCLA had a similar advantage in 1968 and 1972 when it advanced to the Final Four at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena, not many miles from the Bruins' homecourt of Pauley Pavilion (also UCLA's home arena before the latter venue opened in 1965, and again during the 2011–12 season while Pauley was closed for renovations); unlike Louisville and Cal, the Bruins won the national title on both occasions. Butler lost the 2010 title 6 miles (9.7 km) from its Indianapolis campus.

Before the Final Four was established, the east and west regionals were held at separate sites, with the winners advancing to the title game. During that era, three New York City teams, all from Manhattan, played in the east regional at Madison Square Garden—frequently used as a "big-game" venue by each team—and advanced at least to the national semifinals. NYU won the east regional in 1945 but lost in the title game, also held at the Garden, to Oklahoma A&M. CCNY played in the east regional in both 1947 and 1950; the Beavers lost in the 1947 east final to eventual champion Holy Cross but won the 1950 east regional and national titles at the Garden.

In 1974, North Carolina State won the NCAA tournament without leaving its home state of North Carolina. The team was put in the east region, and played its regional games at its home arena Reynolds Coliseum. NC State played the Final Four and national championship games at nearby Greensboro Coliseum.

While not its home state, Kansas has played in the championship game in Kansas City, Missouri, only 45 minutes from the campus in Lawrence, Kansas, on four different occasions. In 1940, 1953, and 1957 the Jayhawks lost the championship game each time at Municipal Auditorium. In 1988, playing at Kansas City's Kemper Arena, Kansas won the championship, over Big Eight–rival Oklahoma. Similarly, in 2005, Illinois played in St. Louis, Missouri, where it enjoyed a noticeable home court advantage, yet still lost in the championship game to North Carolina.

In 2002, Texas was paired with Mississippi State in Dallas despite being the lower seed. The #6 seeded Longhorns defeated the #3 seeded Bulldogs 68–64 in front of a predominately Texas crowd.

The NCAA had banned the Bon Secours Wellness Arena, originally known as Bi-Lo Center, and Colonial Life Arena, originally Colonial Center, in South Carolina from hosting tournament games, despite their sizes (16,000 and 18,000 seats, respectively) because of an NAACP protest at the Bi-Lo Center during the 2002 first and second round tournament games over that state's refusal to completely remove the Confederate Battle Flag from the state capitol grounds, although it had already been relocated from atop the capitol dome to a less prominent place in 2000. Following requests by the NAACP and Black Coaches Association, the Bi-Lo Center, and the newly built Colonial Center, which was built for purposes of hosting the tournament, were banned from hosting any future tournament events.[47] As a result of the removal of the battle flag from the South Carolina State Capitol, the NCAA lifted its ban on South Carolina hosting games in 2015, and it was able to host in 2017 due to North Carolina House Bill 2 (see next section).[48]

On September 12, 2016, the NCAA stripped the state of North Carolina of hosting rights for seven upcoming college sports tournaments and championships held by the association, including early round games of the 2017 NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament scheduled for the Greensboro Coliseum. The NCAA argued that House Bill 2 made it "challenging to guarantee that host communities can help deliver [an inclusive atmosphere]".[49][50] Bon Secours Wellness Arena was able to secure the bid to be the replacement site.[51]

Ahead of the 75th anniversary of the tournament, on December 11, 2012, the NCAA announced the 75 best players, the 25 best teams, and the 35 best moments in tournament history. The NCAA started with a group of more than 100 nominees and then analyzed the tournament statistics for each player to select the 75 finalists from which the public would select the top 15 via an online poll in January 2013.[52]

The results of the public vote were revealed at the 2013 NCAA Final Four.[53][54] Among the 15 players, ten had won a championship, 11 were declared the Most Outstanding Player of the tournament at least once, and all made the Final Four at least once. Abdul-Jabbar, Laettner, Lucas, Olajuwon, and Walton all reached the Final Four in every season they played college basketball, and an additional five players went to multiple Final Fours. Hill, Laettner, Russell, and Walton all won two championships, and Abdul-Jabbar won three championships. Lucas and Walton repeated as Most Outstanding Players, and Abdul-Jabbar was declared the MOP all three seasons he played. Bradley, Lucas, Olajuwon, and West were all declared MOP without winning the championship. Twelve players competed in the tournament every year they played college basketball.

UCLA and Duke are the only team with multiple honorees. Christian Laettner and Grant Hill are the only teammates, they played together for Duke and won two championships in 1991 and 1992. Larry Bird and Magic Johnson competed against each other in the 1979 NCAA Championship Game, and Patrick Ewing and Michael Jordan competed against each other in the 1982 NCAA Championship Game as freshmen. Oscar Robertson and Jerry West competed during the same seasons, but never met in the tournament.

Eleven of the players have been enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the College Basketball Hall of Fame as players. Michael Jordan and Olajuwon have only been enshrined in the Naismith Memorial as players, and Christian Laettner and Danny Manning have only been inducted into the CBHOF as players. Bill Russell has also been enshrined in the Naismith Memorial as a coach.

Patrick Ewing (Georgetown) and Danny Manning (Tulsa and Wake Forest) have appeared in the tournament as head coaches. Manning has also recorded six appearances, two Final Fours, one runner-up, and one championship as an assistant for Kansas.

The NCAA tournament and the Super Bowl are the two American sports events that draw both fans and non-fans.[55][56] Many people are connected to a school in the tournament, having been an alumnus of one of the participants, knowing someone from the college, or living close to the school.[56]

There are pools or private gambling-related contests in which participants predict the outcome of each tournament game, filling out a complete tournament bracket in the process. The popularity of this practice grew around 1985, when the tournament expanded to 64 games, forming four symmetrical regions with 15 games apiece to decide the Final Four.[57] In 2023, Sports Illustrated reported that an estimated 60 to 100 million brackets are filled out each year.[58] Filling out a tournament bracket with predictions is called the practice of "bracketology;" sports programming during the tournament often features commentators comparing the accuracy of their predictions. On The Dan Patrick Show, a wide variety of celebrities from various fields (such as Darius Rucker, Charlie Sheen, Neil Patrick Harris, Ellen DeGeneres, Dave Grohl, and Brooklyn Decker) have posted full brackets with predictions. Former U.S. president Barack Obama began releasing his bracket annually in 2009, his first year in office.[59] While in office, he filled out the men's and women's brackets on ESPN with reporter Andy Katz,[60] and they were also posted on the White House website.[61] He continued releasing his picks after leaving office.[62]

There are many tournament prediction scoring systems. Most award points for correctly picking the winning team in a particular match up, with increasingly more points being given for correctly predicting later round winners. Some provide bonus points for correctly predicting upsets, the amount of the bonus varying based on the degree of upset. Some just provide points for wins by correctly picked teams in the brackets.

There are 2^63 or about 9.22 quintillion unique combinations of winners in a 64-team NCAA bracket, meaning that without considering seed number, the odds of picking a perfect bracket are about 9.22 quintillion to 1.[58] Including the First Four, the number of unique combinations increases to 2^67 or about 147.57 quintillion.

There are numerous awards and prizes given by companies for anyone who can make the perfect bracket. One of the largest was done by a partnership between Quicken Loans and Berkshire Hathaway, which was backed by Warren Buffett, with a $1 billion prize to any person(s) who could correctly predict the outcome of the 2014 tournament. No one was able to complete the challenge and win the $1 billion prize.[63]

During the tournament, American workers take extended lunch breaks at sports bars to follow the game. They also use company computer and internet access to view games, scores, and bracket results. Some workplaces block access to sports and entertainment sites, but the rise of mobile devices and live-streamed games bypassed those restrictions, and even workers not normally in front of computers then had access.[55] Workers spend an estimated average of six hours on the tournament each year,[64] and U.S. employers are projected to lose around $13 billion due to lost productivity during the tournament.[65][66]

As indicated below, none of these phrases are exclusively used in regard to the NCAA tournament. Nonetheless, they are associated widely with the tournament, sometimes for legal reasons, sometimes as part of the American sports vernacular.

March Madness is a popular term for season-ending basketball tournaments played in March. March Madness is also a registered trademark currently owned exclusively by the NCAA.

H. V. Porter, an official with the Illinois High School Association (and later a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame), was the first person to use March Madness to describe a basketball tournament. Porter published an essay named March Madness during 1939, and during 1942, he used the phrase in a poem, Basketball Ides of March. Through the years the use of March Madness increased, especially in Illinois, Indiana, and other parts of the Midwest. During this period the term was used almost exclusively in reference to state high school tournaments. During 1977, Jim Enright published a book about the Illinois tournament entitled March Madness.[67]

Fans began associating the term with the NCAA tournament during the early 1980s. Evidence suggests that CBS sportscaster Brent Musburger, who had worked for many years in Chicago before joining CBS, popularized the term during the annual tournament broadcasts. The NCAA has credited Bob Walsh of the Seattle Organizing Committee for starting the March Madness celebration in 1984.[68]

Only during the 1990s did either the IHSA or the NCAA think about trademarking the term, and by that time a small television production company named Intersport had already trademarked it. IHSA eventually bought the trademark rights from Intersport, and then went to court to establish its primacy. IHSA sued GTE Vantage, an NCAA licensee that used the name March Madness for a computer game based on the college tournament. During 1996, in a historic ruling, Illinois High School Association v. GTE Vantage, Inc., the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit created the concept of a "dual-use trademark", granting both the IHSA and NCAA the right to trademark the term for their own purposes.

After the ruling, the NCAA and IHSA joined forces and created the March Madness Athletic Association to coordinate the licensing of the trademark and investigate possible trademark infringement. One such case involved a company that had obtained the internet domain name marchmadness.com and was using it to post information about the NCAA tournament. During 2003, by March Madness Athletic Association v. Netfire, Inc., the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit decided that March Madness was not a generic term, and ordered Netfire to relinquish the domain name to the NCAA.[69]

Later during the 2000s, the IHSA relinquished its ownership share in the trademark, although it retained the right to use the term in association with high school championships. During October 2010, the NCAA reached a settlement with Intersport, paying $17.2 million for the latter company's license to use the trademark.[70]

This is a popular term for the regional semifinal round of the tournament, consisting of the final 16 teams. As in the case of "March Madness", this was first used by a high school federation—in this case, the Kentucky High School Athletic Association (KHSAA), which has used the term for decades to describe its own season-ending tournaments. It officially registered the trademark in 1988. Unlike the situation with "March Madness", the KHSAA has retained sole ownership of the "Sweet Sixteen" trademark; it licenses the term to the NCAA for use in collegiate tournaments.[71]

The Elite Eight is a popular term to describe the two teams in each of the four regional championship games. The NCAA officially uses the term for the eight-team final phase of the Division II men's and women's basketball tournaments. The winners of these games in the D-I tournament advance to the Final Four (the NCAA does not use the term "Final Four" in D-II). The NCAA trademarked this phrase in 1997. Like "March Madness," the phrase "Elite Eight" originally referred to the Illinois High School Boys Basketball Championship, the single-elimination high school basketball tournament run by the Illinois High School Association. In 1956, when the IHSA finals were reduced from sixteen to eight teams, a new nickname for Sweet Sixteen was needed, and Elite Eight won the vote. The IHSA trademarked the term in 1995; the trademark rights are now held by the March Madness Athletic Association, a joint venture between the NCAA and IHSA formed after a 1996 court case allowed both organizations to use "March Madness" for their own tournaments.

The term Final Four refers to the last four teams remaining in the playoff tournament. These are the champions of the tournament's four regional brackets, and are the only teams remaining on the tournament's final weekend. (While the term "Final Four" was not used during the early decades of the tournament, the term has been applied retroactively to include the last four teams in tournaments from earlier years, even when only two brackets existed.)

Some claim that the phrase Final Four was first used to describe the final games of Indiana's annual high school basketball tournament. But the NCAA, which has a trademark on the term, says Final Four was originated by a Plain Dealer sportswriter, Ed Chay, in a 1975 article that appeared in the Official Collegiate Basketball Guide.[72] The article stated that Marquette University "was one of the final four" of the 1974 tournament. The NCAA started capitalizing the term during 1978 and converting it to a trademark several years later.

During recent years, the term Final Four has been used for other sports besides basketball. Tournaments which use Final Four include the EuroLeague in basketball, national basketball competitions in several European countries, and the now-defunct European Hockey League. Together with the name Final Four, these tournaments have adopted an NCAA-style format in which the four surviving teams compete in a single-elimination tournament held in one place, typically, during one weekend. The derivative term "Frozen Four" is used by the NCAA to refer to the final rounds of the Division I men's and women's ice hockey tournaments. Until 1999, it was just a popular nickname for the last two rounds of the hockey tournament; officially, it was also known as the Final Four.

A Cinderella team, both in NCAA basketball and other sports, is one that achieves far greater success than would reasonably have been best expected.[73][74] In the NCAA tournament, teams may earn the Cinderella title after multiple wins in a single tournament against higher seeded teams. The term first came into widespread usage in 1950, when the City College of New York unexpectedly won the tournament in the same month that a film adaptation of Cinderella was released in the United States.

Notable Cinderella teams include North Carolina State in 1983 (the subject of a 30 for 30 documentary titled Survive and Advance), Villanova in 1985 (the lowest-seeded team to ever win the tournament), LSU in 1986 (the only team to defeat the top three seeds in their region in the same tournament), UMBC in 2018 (the first No. 16 seed to defeat a No. 1 seed), Saint Peter's in 2022 (the first No. 15 seed to advance to the Elite Eight), and Fairleigh Dickinson (the second 16 seed to defeat a 1 seed) and Florida Atlantic (a 9 seed which had never won an NCAA tournament game before its Final Four run) in 2023.[75]

And at one end of the court, there was Kevin Ware on his crutches, the net lowered to accommodate him and his crutches, making the final snip on the only nets Louisville has cut all season.