.jpg/440px-P20220524AS-1533_(52245766080).jpg)

Australia and the United States are close allies, maintaining a robust relationship underpinned by shared democratic values, common interests, and cultural affinities. Economic, academic, and people-to-people ties are vibrant and strong.[1] At the governmental level, relations between Australia and the United States are formalized by the ANZUS security agreement, the AUKUS security partnership and the Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement. They were formally allied together in both World War I & World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the War on Terror, although they had disagreements at the Paris Peace Conference. Australia is a major non-NATO ally of the United States.

Both the United States and Australia share some common ancestry and history (having both been British colonies). Both countries have native peoples who were at times dispossessed of their land by the process of colonization. Both states have also been part of a Western alliance of states in various wars. Together with three other Anglosphere countries, they comprise the Five Eyes espionage and intelligence alliance.

There are dozens of similarities [between America and Australia] ... migrations to a new land, the mystique of pioneering (actually somewhat different in the two countries), the turbulence of gold rushes, the brutality of relaxed restraint, the boredoms of the backblocks, the feeling of making life anew. There may be more similarities between the history of Australia and America than for the moment Australians can understand.

Australian historian Donald Horne, 1964

The political and economic changes brought on by the Great Depression and Second World War, and the adoption of the Statute of Westminster 1931, necessitated the establishment and expansion of Australian representation overseas, independent of the British Foreign & Commonwealth Office. Australia established its first overseas missions (outside London) in January 1940. The first accredited diplomat sent by Australia to any foreign country was Richard Gavin Gardiner Casey,[2] appointed to Washington in January 1940.[3][4]

The US Embassy opened in Canberra in 1943, constructed in a Georgian architectural style.

_as_the_ship_arrives_in_Sydney,_Australia._(48086452031).jpg/440px-Sailors_and_Marines_man_the_rails_aboard_USS_Wasp_(LHD_1)_as_the_ship_arrives_in_Sydney,_Australia._(48086452031).jpg)

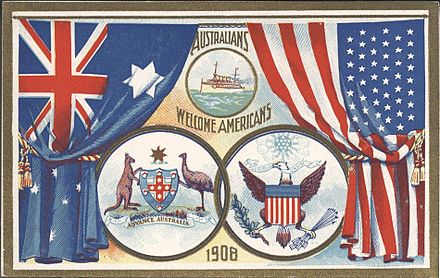

In 1908, Prime Minister Alfred Deakin invited the Great White Fleet to visit Australia during its circumnavigation of the world. The fleet stopped in Sydney, Melbourne and Albany. Deakin, a strong advocate for an independent Australian Navy, used the visit to raise the public's enthusiasm about a new navy.

The visit was significant in that it marked the first occasion that a non-Royal Navy fleet had visited Australian waters. Many saw the visit of the Great White Fleet as a major turning point in the creation of the Royal Australian Navy. Shortly after the visit, Australia ordered its first modern warships, a purchase that angered the British Admiralty.[5]

The United States and Australia both fought in World War I with the Allied Powers. However, at the Paris Peace Conference they disagreed over the peace terms for the Central Powers. While the U.S. delegation under President Woodrow Wilson favored a more conciliatory approach in line with Wilson's Fourteen Points, the Australian delegation under Prime Minister Billy Hughes favored harsher terms such as those advocated by French Premier Georges Clemenceau.[6]

Australia forcefully pressed for higher German reparations and Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles against U.S. opposition.[7] Although U.S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing had guaranteed German leaders that Germany would only be given reparations payments for damages it inflicted, Hughes tried to press for an expansive definition of German "aggression" so that the British Empire and Dominions, including Australia, could benefit.[8] Hughes also opposed Wilson's plans to establish the League of Nations despite French and British support. Australia also demanded that it be allowed to annex German New Guinea as a direct colony rather than a League of Nations mandate, although on this point it was overruled when the United Kingdom and its other Dominions sided with the United States.[9]

During World War II, US General Douglas MacArthur was appointed Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in the South West Pacific Area, which included many Australian troops.[10] After the fall of the Philippines MacArthur's headquarters were located in Brisbane until 1944 and Australian forces remained under MacArthur's overall command until the end of World War II. After the Guadalcanal Campaign, the 1st Marine Division was stationed in Melbourne, and Waltzing Matilda became the division's march.

After the war, the American presence in the southwest Pacific increased immensely, most notably in Japan and the Philippines. In view of the cooperation between the Allies during the war, the decreasing reliance of Australia and New Zealand on the United Kingdom, and America's desire to cement this post-war order in the Pacific, the ANZUS Treaty was signed by Australia, New Zealand and the United States in 1951.[11] This full three-way military alliance replaced the ANZAC Pact that had been in place between Australia and New Zealand since 1944.

Australia, along with New Zealand, has been involved in most major American military endeavors since World War II including the Korean War, Vietnam War, Gulf War and the Iraq War—all without invocation of ANZUS. The alliance has only been invoked once, for the invasion of Afghanistan after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and The Pentagon.[12]

Notably Australia, as a founding member of SEATO, directly supported the United States in the Vietnam War at a time when the United States faced widespread international condemnation from even many of its allies over the war. Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies feared the expansion of communism into Asia-Pacific countries, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, if the communists won the war and a resurgence of isolationism if the United States lost. Under Menzies's successor Harold Holt support for the war waned due to strategic differences between the U.S. Armed Forces and the Australian Defence Force and the changing strategic situation in the region with the 1965 Indonesian coup d'état and founding of ASEAN. In 1967 Holt refused to provide a larger troop commitment after a visit from President Lyndon B. Johnson's advisors Clark Clifford and Maxwell Taylor. Australia's increasing hesitance to continue the war led to its de-escalation and eventually President Richard Nixon's Vietnamization policy.[13]

Following the September 11 attacks, in which eleven Australian citizens were also killed, there was an enormous outpouring of sympathy from Australia for the United States. Prime Minister John Howard became one of President George W. Bush's strongest international supporters, and supported the United States in the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and the Iraq disarmament crisis in 2002–03.[12] Howard, Defence Minister Robert Hill, and Chief of the Defense Force Peter Leahy agreed to participate in the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq through Operation Falconer in order to improve its relationship with the United States despite widespread domestic and international condemnation of the war.[14]

In 2004 the Bush administration "fast tracked" a free trade agreement with Australia. The Sydney Morning Herald called the deal a "reward" for Australia's contribution of troops to the Iraq invasion.[15][16]

However, Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd indicated that the 550 Australian combat troops in Iraq would be removed by mid-2008. Despite this, there have been suggestions from the Australian government that might lead to an increase in numbers of Australian troops in Afghanistan to roughly 1,000.[17]

In 2011, during US President Obama's trip to Australia, it was announced that United States Marine Corps and United States Air Force units will be rotated through Australian Defence Force bases in northern Australia to conduct training. This deployment was criticised by an editorial in the Chinese state-run newspaper People's Daily and Indonesia's foreign minister,[18] but welcomed[18][19] by Australia's Prime Minister. A poll by the independent Lowy Institute think tank showed that a majority (55%) of Australians approving of the marine deployment[20] and 59% supporting the overall military alliance between the two countries.[21]

In 2013, the US Air Force announced rotational deployments of fighter and tanker aircraft through Australia.[22]

Since 1985, there have been annual ministerial consultations between the two countries, known as AUSMIN. The venue of the meeting alternates between the two countries. It is attended by senior government ministers such as the Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs, Australian Minister for Defence, US Secretary of Defense and US Secretary of State.[23]

In late July 2020, Australia's Foreign Minister, Marise Payne, and Defence Minister Linda Reynolds, flew to the US to attend the annual AUSMIN talks with US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Defense Secretary Mark Esper despite concerns about the coronavirus. The year's talks focused on growing tensions with China. In the joint statement following the meetings, the two countries expressed “deep concern” over issues including Hong Kong, Taiwan, the “repression of Uyghurs” in Xinjiang and China's maritime claims in the South China Sea, which are “not valid under international law”.[24][25]

The first Australian visit by a serving United States president[26] was that of Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966 to seek support for Australia's ongoing involvement in the Vietnam War. Australia had previously sent advisers and combat troops to Vietnam. In 1992, George H. W. Bush was the first of four US presidents to address a joint meeting of the Australian Parliament.