Кольца Сатурна являются самой обширной и сложной кольцевой системой среди всех планет Солнечной системы . Они состоят из бесчисленного множества мелких частиц размером от микрометров до метров , [1] которые вращаются вокруг Сатурна . Кольцевые частицы состоят почти полностью из водяного льда с примесью каменистого материала . До сих пор нет единого мнения относительно механизма их образования. Хотя теоретические модели указывали на то, что кольца, вероятно, образовались на ранних этапах истории Солнечной системы, [2] более новые данные с Кассини предполагают, что они образовались относительно поздно. [3]

Хотя отражение от колец увеличивает яркость Сатурна , они не видны с Земли невооруженным глазом . В 1610 году, через год после того, как Галилео Галилей направил телескоп в небо, он стал первым человеком, наблюдавшим кольца Сатурна, хотя он не мог видеть их достаточно хорошо, чтобы различить их истинную природу. В 1655 году Христиан Гюйгенс был первым человеком, который описал их как диск, окружающий Сатурн. [4] Концепция того, что кольца Сатурна состоят из ряда крошечных колечек, может быть прослежена до Пьера-Симона Лапласа , [4] хотя настоящих промежутков мало — правильнее думать о кольцах как о кольцевом диске с концентрическими локальными максимумами и минимумами плотности и яркости. [2] В масштабе сгустков внутри колец много пустого пространства.

Кольца имеют многочисленные щели, где плотность частиц резко падает: две открыты известными лунами, встроенными в них, и многие другие в местах известных дестабилизирующих орбитальных резонансов со лунами Сатурна . Другие щели остаются необъясненными. Стабилизирующие резонансы, с другой стороны, отвечают за долговечность нескольких колец, таких как Кольцо Титана и Кольцо G.

Далеко за главными кольцами находится кольцо Фебы, которое, как предполагается, происходит от Фебы и, таким образом, разделяет ее ретроградное орбитальное движение. Оно совмещено с плоскостью орбиты Сатурна. Сатурн имеет осевой наклон в 27 градусов, поэтому это кольцо наклонено под углом 27 градусов к более видимым кольцам, вращающимся над экватором Сатурна.

В сентябре 2023 года астрономы сообщили об исследованиях, предполагающих, что кольца Сатурна могли образоваться в результате столкновения двух лун «несколько сотен миллионов лет назад». [5] [6]

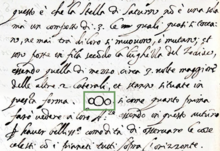

Галилео Галилей был первым, кто наблюдал кольца Сатурна в 1610 году с помощью своего телескопа, но не смог идентифицировать их как таковые. Он написал герцогу Тосканскому , что «планета Сатурн не одинока, а состоит из трех, которые почти касаются друг друга и никогда не двигаются и не изменяются по отношению друг к другу. Они расположены на линии, параллельной зодиаку , а среднее (сам Сатурн) примерно в три раза больше боковых». [7] Он также описал кольца как «уши» Сатурна. В 1612 году Земля прошла через плоскость колец, и они стали невидимыми. Озадаченный, Галилей заметил: «Я не знаю, что сказать в случае столь удивительном, столь неожиданном и столь новом». [4] Он размышлял: «Неужели Сатурн проглотил своих детей?» — ссылаясь на миф о титане Сатурне, пожирающем свое потомство, чтобы предупредить пророчество о его низвержении. [7] [8] Он был еще больше сбит с толку, когда кольца снова стали видны в 1613 году. [4]

Ранние астрономы использовали анаграммы как форму схемы обязательств , чтобы заявить о новых открытиях до того, как их результаты были готовы к публикации. Галилей использовал анаграмму " smaismrmilmepoetaleumibunenugttauiras" для Altissimum planetam tergeminum observavi ("Я наблюдал, что самая далекая планета имеет тройную форму") для открытия колец Сатурна. [9] [10 ] [11 ]

В 1657 году Кристофер Рен стал профессором астрономии в колледже Грешем в Лондоне. Он проводил наблюдения за планетой Сатурн примерно с 1652 года с целью объяснить ее внешний вид. Его гипотеза была изложена в De corpore saturni, в которой он был близок к предположению, что у планеты есть кольцо. Однако Рен не был уверен, было ли кольцо независимым от планеты или физически прикреплено к ней. До того, как гипотеза Рена была опубликована, Христиан Гюйгенс представил свою гипотезу о кольцах Сатурна. Рен сразу же признал ее лучшей гипотезой, чем его собственная, и De corpore saturni так и не был опубликован. Роберт Гук был еще одним ранним наблюдателем колец Сатурна и отметил отбрасывание теней на кольца. [12]

Гюйгенс начал шлифовать линзы вместе со своим отцом Константином в 1655 году и смог наблюдать Сатурн с большей детализацией, используя 43-кратный рефракторный телескоп, который он сконструировал сам. Он был первым, кто предположил, что Сатурн окружен кольцом, отделенным от планеты, и опубликовал знаменитую буквенную строку " aaaaaaacccccdeeeeeghiiiiiiillllmmnnnnnnnnnooooppqrrstttttuuuuu". [13] Три года спустя он раскрыл, что это означает Annulo cingitur , tenui, plano, nusquam coherente, ad eclipticam inclinato ("[Сатурн] окружен тонким, плоским, кольцом, нигде не касающимся [тела планеты], наклоненным к эклиптике"). [14] [4] [15] Он опубликовал свою гипотезу кольца в «Системе Сатурна» (1659), где также было описано его открытие спутника Сатурна, Титана , а также первое четкое описание размеров Солнечной системы . [16]

В 1675 году Джованни Доменико Кассини определил, что кольцо Сатурна состоит из нескольких меньших колец с зазорами между ними; [17] самый большой из этих зазоров позже был назван разделом Кассини. Этот раздел представляет собой область шириной 4800 километров (3000 миль) между кольцом A и кольцом B. [18]

В 1787 году Пьер-Симон Лаплас доказал, что однородное сплошное кольцо будет нестабильным, и предположил, что кольца состоят из большого числа сплошных колечек. [19] [4] [20]

В 1859 году Джеймс Клерк Максвелл продемонстрировал, что неоднородное сплошное кольцо, сплошные колечки или непрерывное жидкое кольцо также не будут стабильными, указывая на то, что кольцо должно состоять из множества мелких частиц, все из которых независимо вращаются вокруг Сатурна. [21] [20] Позднее Софья Ковалевская также обнаружила, что кольца Сатурна не могут быть жидкими кольцеобразными телами. [22] [23] Спектроскопические исследования колец, которые были проведены независимо в 1895 году Джеймсом Килером из обсерватории Аллегейни и Аристархом Белопольским из Пулковской обсерватории, показали, что анализ Максвелла был верен. [24] [25]

Четыре автоматических космических аппарата наблюдали кольца Сатурна из окрестностей планеты. Ближайшее сближение Pioneer 11 с Сатурном произошло в сентябре 1979 года на расстоянии 20 900 км (13 000 миль). [ 26 ] Pioneer 11 был ответственен за открытие кольца F. [26] Ближайшее сближение Voyager 1 произошло в ноябре 1980 года на расстоянии 64 200 км (39 900 миль). [27] Неисправный фотополяриметр не позволил Voyager 1 наблюдать кольца Сатурна с запланированным разрешением; тем не менее, изображения с космического аппарата предоставили беспрецедентную детализацию кольцевой системы и выявили существование кольца G. [28] Ближайшее сближение Voyager 2 произошло в августе 1981 года на расстоянии 41 000 км (25 000 миль). [27] Рабочий фотополяриметр Вояджера-2 позволил ему наблюдать кольцевую систему с более высоким разрешением, чем Вояджер-1 , и тем самым обнаружить множество ранее невиданных колечек. [29] Космический аппарат Кассини вышел на орбиту вокруг Сатурна в июле 2004 года. [30] Изображения колец Кассини являются наиболее подробными на сегодняшний день и позволили обнаружить еще больше колечек. [31]

Кольца названы в алфавитном порядке в порядке их открытия: [32] A и B в 1675 году Джованни Доменико Кассини , C в 1850 году Уильямом Кранчем Бондом и его сыном Джорджем Филлипсом Бондом , D в 1933 году Николаем П. Барабаховым и Б. Семейкиным, E в 1967 году Уолтером А. Фейбельманом, F в 1979 году Пионер-11 и G в 1980 году Вояджер-1 . Главные кольца, если двигаться от планеты, это C, B и A, с разделением Кассини, самым большим промежутком, разделяющим кольца B и A. Несколько более слабых колец были открыты совсем недавно. Кольцо D чрезвычайно слабое и находится ближе всего к планете. Узкое кольцо F находится сразу за кольцом A. За ними находятся два гораздо более слабых кольца, называемых G и E. Кольца демонстрируют огромное количество структур во всех масштабах, некоторые из которых связаны с возмущениями, создаваемыми лунами Сатурна, но многое остается необъяснимым. [32]

В сентябре 2023 года астрономы сообщили об исследованиях, предполагающих, что кольца Сатурна могли образоваться в результате столкновения двух лун «несколько сотен миллионов лет назад». [5] [6]

Наклон оси Сатурна составляет 26,7°, что означает, что с Земли в разное время можно получить самые разные виды колец, из которых видимые занимают его экваториальную плоскость. [33] Земля проходит через плоскость колец каждые 13–15 лет, примерно каждые полгодия Сатурна, и существует примерно равная вероятность того, что в каждом таком случае произойдет одно или три пересечения. Самые последние пересечения плоскости колец были 22 мая 1995 года, 10 августа 1995 года, 11 февраля 1996 года и 4 сентября 2009 года; предстоящие события произойдут 23 марта 2025 года, 15 октября 2038 года, 1 апреля 2039 года и 9 июля 2039 года. Благоприятные возможности для наблюдения за пересечением плоскости колец (когда Сатурн не находится близко к Солнцу) появляются только во время тройных пересечений. [34] [35] [36]

Равноденствия Сатурна , когда Солнце проходит через плоскость колец, неравномерно распределены. Солнце проходит с юга на север через плоскость колец, когда гелиоцентрическая долгота Сатурна составляет 173,6 градуса (например, 11 августа 2009 года), примерно в то время, когда Сатурн переходит из созвездия Льва в созвездие Девы. 15,7 лет спустя долгота Сатурна достигает 353,6 градуса, и Солнце проходит по южной стороне плоскости колец. На каждой орбите Солнце находится к северу от плоскости колец в течение 15,7 земных лет, затем к югу от плоскости в течение 13,7 лет. [a] Даты пересечений с севера на юг включают 19 ноября 1995 года и 6 мая 2025 года, с пересечениями с юга на север 11 августа 2009 года и 23 января 2039 года. [38] В период около равноденствия освещенность большинства колец значительно снижается, что делает возможными уникальные наблюдения, подчеркивающие особенности, которые отклоняются от плоскости колец. [39]

Плотные главные кольца простираются от 7000 км (4300 миль) до 80000 км (50000 миль) от экватора Сатурна, радиус которого составляет 60300 км (37500 миль) (см. Основные подразделения). С предполагаемой локальной толщиной всего 10 метров (32' 10") [40] и до 1 км (1093 ярда), [41] они состоят на 99,9% из чистого водяного льда с небольшим количеством примесей, которые могут включать толины или силикаты . [42] Главные кольца в основном состоят из частиц размером менее 10 м. [43]

Кассини напрямую измерил массу кольцевой системы через их гравитационный эффект во время его последнего набора орбит, которые проходили между кольцами и вершинами облаков, дав значение 1,54 (± 0,49) × 10 19 кг, или 0,41 ± 0,13 массы Мимаса . [3] Это около двух третей массы всего антарктического ледяного покрова Земли , распределенного по площади поверхности в 80 раз большей, чем у Земли. [44] [45] Оценка близка к значению 0,40 массы Мимаса, полученному из наблюдений Кассини за волнами плотности в кольцах A, B и C. [3] Это небольшая часть общей массы Сатурна (около 0,25 ppb ). Более ранние наблюдения «Вояджера» за волнами плотности в кольцах A и B и оптический профиль глубины дали массу около 0,75 массы Мимаса [46] , а более поздние наблюдения и компьютерное моделирование показали, что эта оценка была заниженной. [47]

Хотя самые большие щели в кольцах, такие как щель Кассини и щель Энке, можно увидеть с Земли, космический аппарат Voyager обнаружил, что кольца имеют сложную структуру из тысяч тонких щелей и колечек. Считается, что эта структура возникает несколькими различными способами из-за гравитационного притяжения множества лун Сатурна. Некоторые щели очищаются прохождением крошечных лун, таких как Пан [48], многие из которых еще могут быть обнаружены, а некоторые колечки, по-видимому, поддерживаются гравитационными эффектами небольших спутников-пастухов (подобно поддержанию кольца F Прометеем и Пандорой ). Другие щели возникают из-за резонансов между орбитальным периодом частиц в щели и периодом более массивной луны, расположенной дальше; Мимас поддерживает щель Кассини таким образом. [49] Еще большая часть структуры в кольцах состоит из спиральных волн, поднятых периодическими гравитационными возмущениями внутренних лун при менее разрушительных резонансах. [ необходима цитата ] Данные с космического зонда Кассини указывают на то, что кольца Сатурна обладают собственной атмосферой, независимой от атмосферы самой планеты. Атмосфера состоит из молекулярного газа кислорода (O 2 ), который образуется при взаимодействии ультрафиолетового света Солнца с водяным льдом в кольцах. Химические реакции между фрагментами молекул воды и дальнейшая ультрафиолетовая стимуляция создают и выбрасывают, среди прочего, O 2 . Согласно моделям этой атмосферы, также присутствует H 2 . Атмосферы O 2 и H 2 настолько разрежены, что если бы вся атмосфера каким-то образом была сконденсирована на кольцах, она была бы толщиной около одного атома. [50] Кольца также имеют аналогичную разреженную атмосферу OH (гидроксид). Как и O 2 , эта атмосфера образуется в результате распада молекул воды, хотя в этом случае распад осуществляется энергичными ионами , которые бомбардируют молекулы воды, выброшенные спутником Сатурна Энцеладом . Эта атмосфера, несмотря на то, что она чрезвычайно разрежена, была обнаружена с Земли космическим телескопом Хаббл. [51] Сатурн демонстрирует сложные закономерности в своей яркости. [52] Большая часть изменчивости обусловлена изменением аспекта колец, [53] [54]и это проходит через два цикла на каждой орбите. Однако на это накладывается изменчивость, вызванная эксцентриситетом орбиты планеты, которая заставляет планету демонстрировать более яркие противостояния в северном полушарии, чем в южном. [55]

В 1980 году «Вояджер-1» совершил пролет мимо Сатурна, который показал, что кольцо F состоит из трех узких колец, которые, по-видимому, сплетены в сложную структуру; теперь известно, что два внешних кольца состоят из выступов, изгибов и бугорков, которые создают иллюзию сплетения, а менее яркое третье кольцо находится внутри них. [ необходима ссылка ]

Новые снимки колец, сделанные около равноденствия Сатурна 11 августа 2009 года космическим аппаратом НАСА «Кассини» , показали, что кольца значительно выходят за пределы номинальной плоскости колец в нескольких местах. Это смещение достигает 4 км (2,5 мили) на границе Килеровского разрыва из-за внеплоскостной орбиты Дафниса , луны, которая создает разрыв. [56]

Оценки возраста колец Сатурна сильно различаются в зависимости от используемого подхода. Они считались, возможно, очень старыми, датируемыми образованием самого Сатурна. Однако данные с Кассини предполагают, что они намного моложе, скорее всего, сформировались в течение последних 100 миллионов лет, и, таким образом, могут иметь возраст от 10 миллионов до 100 миллионов лет. [3] [57] Этот недавний сценарий происхождения основан на новом, низкомассовом моделировании динамической эволюции колец и измерениях потока межпланетной пыли, которые вносят вклад в оценку скорости потемнения колец с течением времени. [3] Поскольку кольца постоянно теряют материал, они должны были быть более массивными в прошлом, чем в настоящее время. [3] Оценка массы сама по себе не является очень диагностической, поскольку кольца с большой массой, которые образовались на раннем этапе истории Солнечной системы, к настоящему времени эволюционировали до массы, близкой к измеренной. [3] Исходя из текущих темпов истощения, они могут исчезнуть через 300 миллионов лет. [58] [59]

Существуют две основные теории относительно происхождения внутренних колец Сатурна. Теория, первоначально предложенная Эдуардом Рошем в 19 веке, заключается в том, что кольца когда-то были луной Сатурна (названной Веритас, в честь римской богини , которая пряталась в колодце). Согласно теории, орбита луны деградировала, пока она не оказалась достаточно близко, чтобы быть разорванной приливными силами (см. предел Роша ). [60] Численное моделирование, проведенное в 2022 году, подтверждает эту теорию; авторы этого исследования предложили название « Хризалис » для разрушенной луны. [61] Разновидность этой теории заключается в том, что эта луна распалась после удара крупной кометы или астероида . [62] Вторая теория заключается в том, что кольца никогда не были частью луны, а вместо этого остались от первоначального небулярного материала, из которого образовался Сатурн. [ необходима ссылка ]

Более традиционная версия теории разрушенной луны заключается в том, что кольца состоят из обломков луны диаметром от 400 до 600 км (от 200 до 400 миль), немного больше, чем Мимас . В последний раз столкновения, достаточно крупные, чтобы разрушить луну такого размера, происходили во время поздней тяжелой бомбардировки около четырех миллиардов лет назад. [63]

Более поздний вариант этого типа теории RM Canup заключается в том, что кольца могут представлять собой часть остатков ледяной мантии гораздо более крупной, размером с Титан, дифференцированной луны, которая была лишена своего внешнего слоя, когда она спирально входила в планету в период формирования, когда Сатурн все еще был окружен газообразной туманностью. [64] [65] Это объяснило бы дефицит каменистого материала внутри колец. Кольца изначально были бы намного массивнее (≈1000 раз) и шире, чем в настоящее время; материал во внешних частях колец мог бы объединиться в луны Сатурна вплоть до Тефии , что также объясняет отсутствие каменистого материала в составе большинства этих лун. [65] Последующая коллизионная или криовулканическая эволюция Энцелада могла вызвать выборочную потерю льда на этом спутнике, увеличив его плотность до нынешнего значения 1,61 г/см 3 , по сравнению со значениями 1,15 для Мимаса и 0,97 для Тефии. [65]

Идея массивных ранних колец впоследствии была расширена для объяснения образования спутников Сатурна вплоть до Реи. [66] Если бы первоначальные массивные кольца содержали куски каменистого материала (>100 км; 60 миль в поперечнике), а также лед, эти силикатные тела должны были бы аккрецировать больше льда и быть выброшенными из колец из-за гравитационного взаимодействия с кольцами и приливного взаимодействия с Сатурном на все более широкие орбиты. В пределах предела Роша тела каменистого материала достаточно плотны, чтобы аккрецировать дополнительный материал, тогда как менее плотные тела льда — нет. Оказавшись за пределами колец, вновь образованные луны могли бы продолжать развиваться посредством случайных слияний. Этот процесс может объяснить изменение содержания силиката в лунах Сатурна вплоть до Реи, а также тенденцию к меньшему содержанию силиката ближе к Сатурну. Тогда Рея была бы самой старой из лун, образованных из первичных колец, а луны ближе к Сатурну становились бы все моложе. [66]

Яркость и чистота водяного льда в кольцах Сатурна также были приведены в качестве доказательства того, что кольца намного моложе Сатурна, [57], поскольку падение метеоритной пыли привело бы к потемнению колец. Однако новые исследования показывают, что кольцо B может быть достаточно массивным, чтобы разбавить падающий материал и, таким образом, избежать существенного потемнения на протяжении жизни Солнечной системы. Материал кольца может быть переработан, поскольку комки образуются внутри колец, а затем разрушаются ударами. Это могло бы объяснить кажущуюся молодость части материала внутри колец. [67] Доказательства, предполагающие недавнее происхождение кольца C, были собраны исследователями, проанализировавшими данные с радара Cassini Titan Radar Mapper , который сосредоточился на анализе доли каменистых силикатов в этом кольце. Если большая часть этого материала была внесена недавно разрушенным кентавром или луной, возраст этого кольца может быть порядка 100 миллионов лет или меньше. С другой стороны, если материал поступил в основном из-за притока микрометеоритов, возраст был бы ближе к миллиарду лет. [68]

Команда Cassini UVIS под руководством Ларри Эспозито использовала звездное затмение , чтобы обнаружить 13 объектов размером от 27 метров (89') до 10 км (6 миль) в поперечнике в пределах кольца F. Они полупрозрачны, что позволяет предположить, что это временные скопления ледяных валунов диаметром в несколько метров. Эспозито считает, что это базовая структура колец Сатурна, частицы слипаются вместе, а затем разлетаются на части. [69]

Исследования, основанные на скорости падения на Сатурн, говорят в пользу более молодого возраста кольцевой системы в сотни миллионов лет. Материал колец непрерывно спускается по спирали вниз в Сатурн; чем быстрее это падение, тем короче срок службы кольцевой системы. Один из механизмов включает гравитационное притяжение электрически заряженных частиц водяного льда вниз из колец вдоль линий планетарного магнитного поля, процесс, называемый «кольцевым дождем». Этот расход был выведен как 432–2870 кг/с с использованием наземных наблюдений телескопа Кека ; в результате одного этого процесса кольца исчезнут через ~292+818

−124миллионов лет. [70] Проходя через зазор между кольцами и планетой в сентябре 2017 года, космический аппарат Кассини обнаружил экваториальный поток нейтрального по заряду материала от колец к планете со скоростью 4800–44 000 кг/с. [71] Если предположить, что этот приток стабилен, то добавление его к непрерывному процессу «кольцевого дождя» означает, что кольца могут исчезнуть менее чем за 100 миллионов лет. [70] [72]

Самые плотные части системы колец Сатурна — это кольца A и B, которые разделены разделением Кассини (открыто в 1675 году Джованни Доменико Кассини ). Наряду с кольцом C, которое было открыто в 1850 году и по характеру похоже на разделение Кассини, эти области составляют главные кольца . Главные кольца плотнее и содержат более крупные частицы, чем разреженные пылевые кольца . Последние включают кольцо D, простирающееся внутрь к верхушкам облаков Сатурна, кольца G и E и другие за пределами главной кольцевой системы. Эти диффузные кольца характеризуются как «пыльные» из-за малого размера их частиц (часто около мкм ) ; их химический состав, как и у главных колец, почти полностью состоит из водяного льда. Узкое кольцо F, расположенное недалеко от внешнего края кольца A, сложнее классифицировать; его части очень плотные, но оно также содержит большое количество частиц размером с пыль.

Кольцо D — самое внутреннее кольцо, и оно очень слабое. В 1980 году «Вояджер-1» обнаружил в этом кольце три кольца, обозначенных как D73, D72 и D68, причем D68 было дискретным кольцом, ближайшим к Сатурну. Примерно 25 лет спустя изображения «Кассини» показали, что D72 стало значительно шире и более рассеянным и переместилось в сторону планеты на 200 км (100 миль). [87]

В кольце D присутствует мелкомасштабная структура с волнами на расстоянии 30 км (20 миль) друг от друга. Впервые замеченная в зазоре между кольцом C и D73, [87] структура была обнаружена во время равноденствия Сатурна 2009 года, простирающаяся на радиальное расстояние 19 000 км (12 000 миль) от кольца D до внутреннего края кольца B. [88] [89] Волны интерпретируются как спиральный узор вертикальных гофр амплитудой от 2 до 20 м; [90] тот факт, что период волн со временем уменьшается (с 60 км; 40 миль в 1995 году до 30 км; 20 миль к 2006 году), позволяет сделать вывод, что узор мог возникнуть в конце 1983 года в результате удара облака обломков (массой ≈10 12 кг) от разрушенной кометы, которое наклонило кольца из экваториальной плоскости. [87] [88] [91] Похожий спиральный узор в главном кольце Юпитера был приписан возмущению, вызванному ударом материала кометы Шумейкеров-Леви 9 в 1994 году. [88] [92] [93]

Кольцо C — широкое, но слабое кольцо, расположенное внутри кольца B. Оно было открыто в 1850 году Уильямом и Джорджем Бондами , хотя Уильям Р. Доус и Иоганн Галле также видели его независимо. Уильям Лассел назвал его «Креповым кольцом», потому что оно, казалось, состояло из более темного материала, чем более яркие кольца A и B. [77]

Его вертикальная толщина оценивается в 5 метров (16 футов), его масса составляет около 1,1 × 10 18 кг, а его оптическая глубина варьируется от 0,05 до 0,12. [ необходима цитата ] То есть, от 5 до 12 процентов света, проходящего перпендикулярно через кольцо, блокируется, так что при взгляде сверху кольцо становится почти прозрачным. Спиральные гофры с длиной волны 30 км, впервые замеченные в кольце D, наблюдались во время равноденствия Сатурна в 2009 году и простирались по всему кольцу C (см. выше).

Colombo Gap находится во внутреннем кольце C. Внутри щели находится яркое, но узкое колечко Colombo Ringlet, центр которого находится в 77 883 км (48 394 мили) от центра Сатурна, которое имеет слегка эллиптическую, а не круглую форму. Это колечко также называют Titan Ringlet, поскольку оно управляется орбитальным резонансом с луной Титаном . [94] В этом месте внутри колец длина апсидальной прецессии кольцевой частицы равна длине орбитального движения Титана, так что внешний конец этого эксцентричного колечка всегда указывает на Титан. [94]

Максвелл-Гэп находится внутри внешней части кольца C. Он также содержит плотное некруглое колечко, Максвелл-Кольцо. Во многих отношениях это колечко похоже на кольцо ε Урана . В середине обоих колец есть волнообразные структуры. Хотя волна в кольце ε, как полагают, вызвана луной Урана Корделией , по состоянию на июль 2008 года в Максвелл-Кольце не было обнаружено ни одной луны. [95]

The B Ring is the largest, brightest, and most massive of the rings. Its thickness is estimated as 5 to 15 m and its optical depth varies from 0.4 to greater than 5,[96] meaning that >99% of the light passing through some parts of the B Ring is blocked. The B Ring contains a great deal of variation in its density and brightness, nearly all of it unexplained. These are concentric, appearing as narrow ringlets, though the B Ring does not contain any gaps.[citation needed] In places, the outer edge of the B Ring contains vertical structures deviating up to 2.5 km (1½ miles) from the main ring plane, a significant deviation from the vertical thickness of the main A, B and C rings, which is generally only about 10 meters (about 30 feet). Vertical structures can be created by unseen embedded moonlets.[97]

A 2016 study of spiral density waves using stellar occultations indicated that the B Ring's surface density is in the range of 40 to 140 g/cm2, lower than previously believed, and that the ring's optical depth has little correlation with its mass density (a finding previously reported for the A and C rings).[96][98] The total mass of the B Ring was estimated to be somewhere in the range of 7 to 24×1018 kg. This compares to a mass for Mimas of 37.5×1018 kg.[96]

Until 1980, the structure of the rings of Saturn was explained as being caused exclusively by the action of gravitational forces. Then images from the Voyager spacecraft showed radial features in the B Ring, known as spokes,[99][100] which could not be explained in this manner, as their persistence and rotation around the rings was not consistent with gravitational orbital mechanics.[101] The spokes appear dark in backscattered light, and bright in forward-scattered light (see images in Gallery); the transition occurs at a phase angle near 60°. The leading theory regarding the spokes' composition is that they consist of microscopic dust particles suspended away from the main ring by electrostatic repulsion, as they rotate almost synchronously with the magnetosphere of Saturn. The precise mechanism generating the spokes is still unknown. It has been suggested that the electrical disturbances might be caused by either lightning bolts in Saturn's atmosphere or micrometeoroid impacts on the rings.[101] Alternatively, it is proposed that the spokes are very similar to a phenomenon known as lunar horizon glow or dust levitation, and caused by intense electric fields across the terminator of ring particles, not electrical disturbances.[102]

The spokes were not observed again until some twenty-five years later, this time by the Cassini space probe. The spokes were not visible when Cassini arrived at Saturn in early 2004. Some scientists speculated that the spokes would not be visible again until 2007, based on models attempting to describe their formation. Nevertheless, the Cassini imaging team kept looking for spokes in images of the rings, and they were next seen in images taken on 5 September 2005.[103]

The spokes appear to be a seasonal phenomenon, disappearing in the Saturnian midwinter and midsummer and reappearing as Saturn comes closer to equinox. Suggestions that the spokes may be a seasonal effect, varying with Saturn's 29.7-year orbit, were supported by their gradual reappearance in the later years of the Cassini mission.[104]

In 2009, during equinox, a moonlet embedded in the B ring was discovered from the shadow it cast. It is estimated to be 400 m (1,300 ft) in diameter.[105] The moonlet was given the provisional designation S/2009 S 1.

The Cassini Division is a region 4,800 km (3,000 mi) in width between Saturn's A Ring and B Ring. It was discovered in 1675 by Giovanni Cassini at the Paris Observatory using a refracting telescope that had a 2.5-inch objective lens with a 20-foot-long focal length and a 90x magnification.[106][107] From Earth it appears as a thin black gap in the rings. However, Voyager discovered that the gap is itself populated by ring material bearing much similarity to the C Ring.[95] The division may appear bright in views of the unlit side of the rings, since the relatively low density of material allows more light to be transmitted through the thickness of the rings (see second image in gallery).[citation needed]

The inner edge of the Cassini Division is governed by a strong orbital resonance. Ring particles at this location orbit twice for every orbit of the moon Mimas.[108] The resonance causes Mimas' pulls on these ring particles to accumulate, destabilizing their orbits and leading to a sharp cutoff in ring density. Many of the other gaps between ringlets within the Cassini Division, however, are unexplained.[109]

Discovered in 1981 through images sent back by Voyager 2,[110] the Huygens Gap is located at the inner edge of the Cassini Division. It contains the dense, eccentric Huygens Ringlet in the middle. This ringlet exhibits irregular azimuthal variations of geometrical width and optical depth, which may be caused by the nearby 2:1 resonance with Mimas and the influence of the eccentric outer edge of the B-ring. There is an additional narrow ringlet just outside the Huygens Ringlet.[95]

The A Ring is the outermost of the large, bright rings. Its inner boundary is the Cassini Division and its sharp outer boundary is close to the orbit of the small moon Atlas. The A Ring is interrupted at a location 22% of the ring width from its outer edge by the Encke Gap. A narrower gap 2% of the ring width from the outer edge is called the Keeler Gap.

The thickness of the A Ring is estimated to be 10 to 30 m, its surface density from 35 to 40 g/cm2 and its total mass as 4 to 5×1018 kg[96] (just under the mass of Hyperion). Its optical depth varies from 0.4 to 0.9.[96]

Similarly to the B Ring, the A Ring's outer edge is maintained by orbital resonances, albeit in this case a more complicated set. It is primarily acted on by the 7:6 resonance with Janus and Epimetheus, with other contributions from the 5:3 resonance with Mimas and various resonances with Prometheus and Pandora.[111][112] Other orbital resonances also excite many spiral density waves in the A Ring (and, to a lesser extent, other rings as well), which account for most of its structure. These waves are described by the same physics that describes the spiral arms of galaxies. Spiral bending waves, also present in the A Ring and also described by the same theory, are vertical corrugations in the ring rather than compression waves.[113]

In April 2014, NASA scientists reported observing the possible formative stage of a new moon near the outer edge of the A Ring.[114][115]

The Encke Gap is a 325-km (200 mile) wide gap within the A ring, centered at a distance of 133,590 km (83,000 miles) from Saturn's center.[117] It is caused by the presence of the small moon Pan,[118] which orbits within it. Images from the Cassini probe have shown that there are at least three thin, knotted ringlets within the gap.[95] Spiral density waves visible on both sides of it are induced by resonances with nearby moons exterior to the rings, while Pan induces an additional set of spiraling wakes (see image in gallery).[95]

Johann Encke himself did not observe this gap; it was named in honour of his ring observations. The gap itself was discovered by James Edward Keeler in 1888.[77] The second major gap in the A ring, discovered by Voyager, was named the Keeler Gap in his honor.[119]

The Encke Gap is a gap because it is entirely within the A Ring. There was some ambiguity between the terms gap and division until the IAU clarified the definitions in 2008; before that, the separation was sometimes called the "Encke Division".[120]

The Keeler Gap is a 42-km (26 mile) wide gap in the A ring, approximately 250 km (150 miles) from the ring's outer edge. The small moon Daphnis, discovered 1 May 2005, orbits within it, keeping it clear.[121] The moon's passage induces waves in the edges of the gap (this is also influenced by its slight orbital eccentricity).[95] Because the orbit of Daphnis is slightly inclined to the ring plane, the waves have a component that is perpendicular to the ring plane, reaching a distance of 1500 m "above" the plane.[122][123]

The Keeler gap was discovered by Voyager, and named in honor of the astronomer James Edward Keeler. Keeler had in turn discovered and named the Encke Gap in honor of Johann Encke.[77]

In 2006, four tiny "moonlets" were found in Cassini images of the A Ring.[124] The moonlets themselves are only about a hundred metres in diameter, too small to be seen directly; what Cassini sees are the "propeller"-shaped disturbances the moonlets create, which are several km (miles) across. It is estimated that the A Ring contains thousands of such objects. In 2007, the discovery of eight more moonlets revealed that they are largely confined to a 3,000 km (2000 mile) belt, about 130,000 km (80,000 miles) from Saturn's center,[125] and by 2008 over 150 propeller moonlets had been detected.[126] One that has been tracked for several years has been nicknamed Bleriot.[127]

The separation between the A ring and the F Ring has been named the Roche Division in honor of the French physicist Édouard Roche.[128] The Roche Division should not be confused with the Roche limit which is the distance at which a large object is so close to a planet (such as Saturn) that the planet's tidal forces will pull it apart.[129] Lying at the outer edge of the main ring system, the Roche Division is in fact close to Saturn's Roche limit, which is why the rings have been unable to accrete into a moon.[130]

Like the Cassini Division, the Roche Division is not empty but contains a sheet of material.[citation needed] The character of this material is similar to the tenuous and dusty D, E, and G Rings.[citation needed] Two locations in the Roche Division have a higher concentration of dust than the rest of the region. These were discovered by the Cassini probe imaging team and were given temporary designations: R/2004 S 1, which lies along the orbit of the moon Atlas; and R/2004 S 2, centered at 138,900 km (86,300 miles) from Saturn's center, inward of the orbit of Prometheus.[131][132]

The F Ring is the outermost discrete ring of Saturn and perhaps the most active ring in the Solar System, with features changing on a timescale of hours.[133] It is located 3,000 km (2000 miles) beyond the outer edge of the A ring.[134] The ring was discovered in 1979 by the Pioneer 11 imaging team.[80] It is very thin, just a few hundred km (miles) in radial extent. While the traditional view has been that it is held together by two shepherd moons, Prometheus and Pandora, which orbit inside and outside it,[118] recent studies indicate that only Prometheus contributes to the confinement.[135][136] Numerical simulations suggest the ring was formed when Prometheus and Pandora collided with each other and were partially disrupted.[137]

More recent closeup images from the Cassini probe show that the F Ring consists of one core ring and a spiral strand around it.[138] They also show that when Prometheus encounters the ring at its apoapsis, its gravitational attraction creates kinks and knots in the F Ring as the moon 'steals' material from it, leaving a dark channel in the inner part of the ring (see video link and additional F Ring images in gallery). Since Prometheus orbits Saturn more rapidly than the material in the F ring, each new channel is carved about 3.2 degrees in front of the previous one.[133]

In 2008, further dynamism was detected, suggesting that small unseen moons orbiting within the F Ring are continually passing through its narrow core because of perturbations from Prometheus. One of the small moons was tentatively identified as S/2004 S 6.[133]

As of 2023, the clumpy structure of the ring "is thought to be caused by the presence of thousands of small parent bodies (1.0 to 0.1 km in size) that collide and produce dense strands of micrometre- to centimetre-sized particles that re-accrete over a few months onto the parent bodies in a steady-state regime."[139]

A faint dust ring is present around the region occupied by the orbits of Janus and Epimetheus, as revealed by images taken in forward-scattered light by the Cassini spacecraft in 2006. The ring has a radial extent of about 5,000 km (3000 miles).[140] Its source is particles blasted off the moons' surfaces by meteoroid impacts, which then form a diffuse ring around their orbital paths.[141]

The G Ring (see last image in gallery) is a very thin, faint ring about halfway between the F Ring and the beginning of the E Ring, with its inner edge about 15,000 km (10,000 miles) inside the orbit of Mimas. It contains a single distinctly brighter arc near its inner edge (similar to the arcs in the rings of Neptune) that extends about one-sixth of its circumference, centered on the half-km (500 yard) diameter moonlet Aegaeon, which is held in place by a 7:6 orbital resonance with Mimas.[142][143] The arc is believed to be composed of icy particles up to a few m in diameter, with the rest of the G Ring consisting of dust released from within the arc. The radial width of the arc is about 250 km (150 miles), compared to a width of 9,000 km (6000 miles) for the G Ring as a whole.[142] The arc is thought to contain matter equivalent to a small icy moonlet about a hundred m in diameter.[142] Dust released from Aegaeon and other source bodies within the arc by micrometeoroid impacts drifts outward from the arc because of interaction with Saturn's magnetosphere (whose plasma corotates with Saturn's magnetic field, which rotates much more rapidly than the orbital motion of the G Ring). These tiny particles are steadily eroded away by further impacts and dispersed by plasma drag. Over the course of thousands of years the ring gradually loses mass,[144] which is replenished by further impacts on Aegaeon.

A faint ring arc, first detected in September 2006, covering a longitudinal extent of about 10 degrees is associated with the moon Methone. The material in the arc is believed to represent dust ejected from Methone by micrometeoroid impacts. The confinement of the dust within the arc is attributable to a 14:15 resonance with Mimas (similar to the mechanism of confinement of the arc within the G ring).[145][146] Under the influence of the same resonance, Methone librates back and forth in its orbit with an amplitude of 5° of longitude.

A faint ring arc, first detected in June 2007, covering a longitudinal extent of about 20 degrees is associated with the moon Anthe. The material in the arc is believed to represent dust knocked off Anthe by micrometeoroid impacts. The confinement of the dust within the arc is attributable to a 10:11 resonance with Mimas. Under the influence of the same resonance, Anthe drifts back and forth in its orbit over 14° of longitude.[145][146]

A faint dust ring shares Pallene's orbit, as revealed by images taken in forward-scattered light by the Cassini spacecraft in 2006.[140] The ring has a radial extent of about 2,500 km (1500 miles). Its source is particles blasted off Pallene's surface by meteoroid impacts, which then form a diffuse ring around its orbital path.[141][146]

Although not confirmed until 1980,[82] the existence of the E ring was a subject of debate among astronomers at least as far back as 1908. In a narrative timeline of Saturn observations, Arthur Francis O'Donel Alexander attributes[147] the first observation of what would come to be called the E Ring to Georges Fournier, who on 5 September 1907 at Mont Revard observed a "luminous zone" "surrounding the outer bright ring." The next year, on 7 October 1908, E. Schaer independently observed "a new dusky ring...surrounding the bright rings of Saturn" at the Geneva Observatory. Following up on Schaer's discovery, W. Boyer, T. Lewis, and Arthur Eddington found signs of a discontinuous ring matching Schaer's description, but described their observations as "uncertain." After Edward Barnard, using the what was at the time the world's best telescope, failed to find signs of a ring. E. M. Antoniadi argued for the ring's existence in a 1909 publication, recalling a observations by William Wray on 26 December 1861 of a "very faint light...so as to give the impression that it was the dusky ring,"[148][149] but after Barnard's negative result most astronomers became skeptical of the E Ring's existence.[147]

Unlike the A, B, and C rings, the E Ring's small optical depth and large vertical extent mean it is best viewed edge-on, which is only possible once every 14–15 years,[150] so perhaps for this reason, it was not until the 1960's that the E Ring was again the subject of observations. Although some sources credit Walter Feibelman with the E Ring's discovery in 1966,[4][32] his paper published the following year announcing the observations begins by acknowledging the existing controversy and the long record of observations both supporting and disputing the ring's existence, and carefully stresses his interpretation of the data as a new ring as "tentative only."[150] A reanalysis of Feibelman's original observations, conducted in anticipation of the coming Saturn flyby by Pioneer 11, once again called the evidence for this outer ring "shaky."[151] Even polarimetric observations by Pioneer 11 failed to conclusively identify E Ring during its 1979 flyby, though "its existence was inferred from [particle, radiation, and magnetic field measurements]."[82] Only after a digital reanalysis of the 1966 observations as well as several independent observations using ground- and space-based telescopes existence was finally confirmed in a 1980 paper by Feibelman and Klinglesmith.[82]

The E Ring is the second outermost ring and is extremely wide; it consists of many tiny (micron and sub-micron) particles of water ice with silicates, carbon dioxide and ammonia.[152] The E Ring is distributed between the orbits of Mimas and Titan.[153] Unlike the other rings, it is composed of microscopic particles rather than macroscopic ice chunks. In 2005, the source of the E Ring's material was determined to be cryovolcanic plumes[154][155] emanating from the "tiger stripes" of the south polar region of the moon Enceladus.[156] Unlike the main rings, the E Ring is more than 2,000 km (1000 miles) thick and increases with its distance from Enceladus.[153] Tendril-like structures observed within the E Ring can be related to the emissions of the most active south polar jets of Enceladus.[157]

Particles of the E Ring tend to accumulate on moons that orbit within it. The equator of the leading hemisphere of Tethys is tinted slightly blue due to infalling material.[158] The trojan moons Telesto, Calypso, Helene and Polydeuces are particularly affected as their orbits move up and down the ring plane. This results in their surfaces being coated with bright material that smooths out features.[159]

In October 2009, the discovery of a tenuous disk of material just interior to the orbit of Phoebe was reported. The disk was aligned edge-on to Earth at the time of discovery. This disk can be loosely described as another ring. Although very large (as seen from Earth, the apparent size of two full moons[85]), the ring is virtually invisible. It was discovered using NASA's infrared Spitzer Space Telescope,[160] and was seen over the entire range of the observations, which extended from 128 to 207 times the radius of Saturn,[84] with calculations indicating that it may extend outward up to 300 Saturn radii and inward to the orbit of Iapetus at 59 Saturn radii.[161] The ring was subsequently studied using the WISE, Herschel and Cassini spacecraft;[162] WISE observations show that it extends from at least between 50 and 100 to 270 Saturn radii (the inner edge is lost in the planet's glare).[83] Data obtained with WISE indicate the ring particles are small; those with radii greater than 10 cm comprise 10% or less of the cross-sectional area.[83]

Phoebe orbits the planet at a distance ranging from 180 to 250 radii. The ring has a thickness of about 40 radii.[163] Because the ring's particles are presumed to have originated from impacts (micrometeoroid and larger) on Phoebe, they should share its retrograde orbit,[161] which is opposite to the orbital motion of the next inner moon, Iapetus. This ring lies in the plane of Saturn's orbit, or roughly the ecliptic, and thus is tilted 27 degrees from Saturn's equatorial plane and the other rings. Phoebe is inclined by 5° with respect to Saturn's orbit plane (often written as 175°, due to Phoebe's retrograde orbital motion), and its resulting vertical excursions above and below the ring plane agree closely with the ring's observed thickness of 40 Saturn radii.

The existence of the ring was proposed in the 1970s by Steven Soter.[161] The discovery was made by Anne J. Verbiscer and Michael F. Skrutskie (of the University of Virginia) and Douglas P. Hamilton (of the University of Maryland, College Park).[84][164] The three had studied together at Cornell University as graduate students.[165]

Ring material migrates inward due to reemission of solar radiation,[84] with a speed inversely proportional to particle size; a 3 cm particle would migrate from the vicinity of Phoebe to that of Iapetus over the age of the Solar System.[83] The material would thus strike the leading hemisphere of Iapetus. Infall of this material causes a slight darkening and reddening of the leading hemisphere of Iapetus (similar to what is seen on the Uranian moons Oberon and Titania) but does not directly create the dramatic two-tone coloration of that moon.[166] Rather, the infalling material initiates a positive feedback thermal self-segregation process of ice sublimation from warmer regions, followed by vapor condensation onto cooler regions. This leaves a dark residue of "lag" material covering most of the equatorial region of Iapetus's leading hemisphere, which contrasts with the bright ice deposits covering the polar regions and most of the trailing hemisphere.[167][168][169]

Saturn's second largest moon Rhea has been hypothesized to have a tenuous ring system of its own consisting of three narrow bands embedded in a disk of solid particles.[170][171] These putative rings have not been imaged, but their existence has been inferred from Cassini observations in November 2005 of a depletion of energetic electrons in Saturn's magnetosphere near Rhea. The Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument (MIMI) observed a gentle gradient punctuated by three sharp drops in plasma flow on each side of the moon in a nearly symmetric pattern. This could be explained if they were absorbed by solid material in the form of an equatorial disk containing denser rings or arcs, with particles perhaps several decimeters to approximately a meter in diameter. A more recent piece of evidence consistent with the presence of Rhean rings is a set of small ultraviolet-bright spots distributed in a line that extends three quarters of the way around the moon's circumference, within 2 degrees of the equator. The spots have been interpreted as the impact points of deorbiting ring material.[172] However, targeted observations by Cassini of the putative ring plane from several angles have turned up nothing, suggesting that another explanation for these enigmatic features is needed.[173]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)A prolongation of very faint light stretched on either side from the dark shade on the ball, overlapping the fine line of light formed by the edge of the ring, to the extent of about one-third its length, and so as to give the impression that it was the dusky ring, very much thicker than the bright rings, and seen edgewise, projected on the sky.