Moroccan Arabic (Arabic: العربية المغربية الدارجة, romanized: al-ʻArabiyyah al-Maghribiyyah ad-Dārija[3] lit. 'Moroccan vernacular Arabic'), also known as Darija (الدارجة or الداريجة[3]), is the dialectal, vernacular form or forms of Arabic spoken in Morocco.[4][5] It is part of the Maghrebi Arabic dialect continuum and as such is mutually intelligible to some extent with Algerian Arabic and to a lesser extent with Tunisian Arabic. It is spoken by 90.9% of the population of Morocco.[6] While Modern Standard Arabic is used to varying degrees in formal situations such as religious sermons, books, newspapers, government communications, news broadcasts and political talk shows, Moroccan Arabic is the predominant spoken language of the country and has a strong presence in Moroccan television entertainment, cinema and commercial advertising. Moroccan Arabic has many regional dialects and accents as well, with its mainstream dialect being the one used in Casablanca, Rabat, Tangier, Marrakesh and Fez, and therefore it dominates the media and eclipses most of the other regional accents.

SIL International classifies Moroccan Arabic, Hassaniya Arabic and Judeo-Moroccan Arabic as different varieties of Arabic.

Moroccan Arabic was formed of several dialects of Arabic belonging to two genetically different groups: pre-Hilalian and Hilalian dialects.[7][8][9]

Pre-Hilalian dialects are a result of early Arabization phases of the Maghreb, from the 7th to the 12th centuries, concerning the main urban settlements, the harbors, the religious centres (zaouias) as well as the main trade routes. The dialects are generally classified in three types: (old) urban, "village" and "mountain" sedentary and Jewish dialects.[8][10] In Morocco, several pre-Hilalian dialects are spoken:

Hilalian dialects (Bedouin dialects) were introduced following the migration of Arab nomadic tribes to Morocco in the 11th century, particularly the Banu Hilal, which the Hilalian dialects are named after.[15][10]

The Hilalian dialects spoken in Morocco belong to the Maqil subgroup,[10] a family that includes three main dialectal areas:

One of the most notable features of Moroccan Arabic is the collapse of short vowels. Initially, short /a/ and /i/ were merged into a phoneme /ə/ (however, some speakers maintain a difference between /a/ and /ə/ when adjacent to pharyngeal /ʕ/ and /ħ/). This phoneme (/ə/) was then deleted entirely in most positions; for the most part, it is maintained only in the position /...CəC#/ or /...CəCC#/ (where C represents any consonant and # indicates a word boundary), i.e. when appearing as the last vowel of a word. When /ə/ is not deleted, it is pronounced as a very short vowel, tending towards [ɑ] in the vicinity of emphatic consonants, [a] in the vicinity of pharyngeal /ʕ/ and /ħ/ (for speakers who have merged /a/ and /ə/ in this environment), and [ə] elsewhere. Original short /u/ usually merges with /ə/ except in the vicinity of a labial or velar consonant. In positions where /ə/ was deleted, /u/ was also deleted, and is maintained only as labialization of the adjacent labial or velar consonant; where /ə/ is maintained, /u/ surfaces as [ʊ]. This deletion of short vowels can result in long strings of consonants (a feature shared with Berber and certainly derived from it). These clusters are never simplified; instead, consonants occurring between other consonants tend to syllabify, according to a sonorance hierarchy. Similarly, and unlike most other Arabic dialects, doubled consonants are never simplified to a single consonant, even when at the end of a word or preceding another consonant.

Some dialects are more conservative in their treatment of short vowels. For example, some dialects allow /u/ in more positions. Dialects of the Sahara, and eastern dialects near the border of Algeria, preserve a distinction between /a/ and /i/ and allow /a/ to appear at the beginning of a word, e.g. /aqsˤarˤ/ "shorter" (standard /qsˤərˤ/), /atˤlaʕ/ "go up!" (standard /tˤlaʕ/ or /tˤləʕ/), /asˤħaːb/ "friends" (standard /sˤħab/).

Long /aː/, /iː/ and /uː/ are maintained as semi-long vowels, which are substituted for both short and long vowels in most borrowings from Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Long /aː/, /iː/ and /uː/ also have many more allophones than in most other dialects; in particular, /aː/, /iː/, /uː/ appear as [ɑ], [e], [o] in the vicinity of emphatic consonants and [q], [χ], [ʁ], [r], but [æ], [i], [u] elsewhere. (Most other Arabic dialects only have a similar variation for the phoneme /aː/.) In some dialects, such as that of Marrakech, front-rounded and other allophones also exist. Allophones in vowels usually do not exist in loanwords.

Emphatic spreading (i.e. the extent to which emphatic consonants affect nearby vowels) occurs much less than in Egyptian Arabic. Emphasis spreads fairly rigorously towards the beginning of a word and into prefixes, but much less so towards the end of a word. Emphasis spreads consistently from a consonant to a directly following vowel, and less strongly when separated by an intervening consonant, but generally does not spread rightwards past a full vowel. For example, /bidˤ-at/ [bedɑt͡s] "eggs" (/i/ and /a/ both affected), /tˤʃaʃ-at/ [tʃɑʃæt͡s] "sparks" (rightmost /a/ not affected), /dˤrˤʒ-at/ [drˤʒæt͡s] "stairs" (/a/ usually not affected), /dˤrb-at-u/ [drˤbat͡su] "she hit him" (with [a] variable but tending to be in between [ɑ] and [æ]; no effect on /u/), /tˤalib/ [tɑlib] "student" (/a/ affected but not /i/). Contrast, for example, Egyptian Arabic, where emphasis tends to spread forward and backward to both ends of a word, even through several syllables.

Emphasis is audible mostly through its effects on neighboring vowels or syllabic consonants, and through the differing pronunciation of /t/ [t͡s] and /tˤ/ [t]. Actual pharyngealization of "emphatic" consonants is weak and may be absent entirely. In contrast with some dialects, vowels adjacent to emphatic consonants are pure; there is no diphthong-like transition between emphatic consonants and adjacent front vowels.

Phonetic notes:

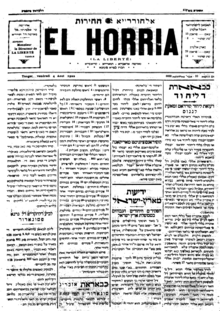

Through most of its history, Moroccan vernacular Arabic has usually not been written.[19]: 59 Due to the diglossic nature of the Arabic language, most literate Muslims in Morocco would write in Standard Arabic, even if they spoke Darija as a first language.[19]: 59 However, since Standard Arabic was typically taught in Islamic religious contexts, Moroccan Jews usually would not learn Standard Arabic and would write instead in Darija, or more specifically a variety known as Judeo-Moroccan Arabic, using Hebrew script.[19]: 59 A risala on Semitic languages written in Maghrebi Judeo-Arabic by Judah ibn Quraish to the Jews of Fes dates back to the ninth-century.[19]: 59

Al-Kafif az-Zarhuni's epic 14th century zajal Mala'bat al-Kafif az-Zarhuni, about Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman al-Marini's campaign on Hafsid Ifriqiya, is considered the first literary work in Darija.[20][21]

Most books and magazines are in Modern Standard Arabic; Qur'an books are written and read in Classical Arabic, and there is no universally standard written system for Darija. There is also a loosely standardized Latin system used for writing Moroccan Arabic in electronic media, such as texting and chat, often based on sound-letter correspondences from French, English or Spanish ('sh' or 'ch' for English 'sh', 'u' or 'ou' for English 'oo', etc.) and using numbers to represent sounds not found in French or English (2-3-7-9 used for ق-ح-ع-ء, respectively.).

In the last few years, there have been some publications in Moroccan Darija, such as Hicham Nostik's Notes of a Moroccan Infidel, as well as basic science books by Moroccan physics professor Farouk El Merrakchi.[22] Newspapers in Moroccan Arabic also exist, such as Souq Al Akhbar, Al Usbuu Ad-Daahik,[23] the regional newspaper Al Amal (formerly published by Latifa Akherbach), and Khbar Bladna (news of our country), which was published by Tangier-based American painter Elena Prentice between 2002 and 2006.[24]

The latter also published books written in Moroccan Arabic, mostly novels and stories, written by authors such as Kenza El Ghali and Youssef Amine Alami.[24]

Moroccan Arabic is characterized by a strong Berber, as well as Latin (African Romance), substratum.[25]

Following the Arab conquest, Berber languages remained widely spoken. During their Arabisation, some Berber tribes became bilingual for generations before abandoning their language for Arabic; however, they kept a substantial Berber stratum that increases from the east to the west of the Maghreb, making Moroccan Arabic dialects the ones most influenced by Berber.

More recently, the influx of Andalusi people and Spanish-speaking–Moriscos (between the 15th and the 17th centuries) influenced urban dialects with Spanish substrate (and loanwords).

The vocabulary of Moroccan Arabic is mostly Semitic and derived from Classical Arabic.[26] It also contains many Berber loanwords which represent 10% to 15% of its vocabulary,[27] supplemented by French and Spanish loanwords.

There are noticeable lexical differences between Moroccan Arabic and most other Arabic languages. Some words are essentially unique to Moroccan Arabic: daba "now". Many others, however, are characteristic of Maghrebi Arabic as a whole including both innovations and unusual retentions of Classical vocabulary that disappeared elsewhere, such as hbeṭ' "go down" from Classical habaṭ. Others are shared with Algerian Arabic such as hḍeṛ "talk", from Classical hadhar "babble", and temma "there", from Classical thamma.

There are a number of Moroccan Arabic dictionaries in existence:

Some loans might have come through Andalusi Arabic brought by Moriscos when they were expelled from Spain following the Christian Reconquest or, alternatively, they date from the time of the Spanish protectorate in Morocco.

They are used in several coastal cities across the Moroccan coast like Oualidia, El Jadida, and Tangier.

It is also used as a compliment in northern Morocco

Note: All sentences are written according to the transcription used in Richard Harrell, A Short Reference Grammar of Moroccan Arabic (Examples with their pronunciation).:[28]

The regular Moroccan Arabic verb conjugates with a series of prefixes and suffixes. The stem of the conjugated verb may change a bit, depending on the conjugation:

The stem of the Moroccan Arabic verb for "to write" is kteb.

The past tense of kteb (write) is as follows:

I wrote: kteb-t

You wrote: kteb-ti (some regions tend to differentiate between masculine and feminine, the masculine form is kteb-t, the feminine kteb-ti)

He/it wrote: kteb (can also be an order to write; kteb er-rissala: Write the letter)

She/it wrote: ketb-et

We wrote: kteb-na

You (plural) wrote: kteb-tu / kteb-tiu

They wrote: ketb-u

The stem kteb turns into ketb before a vowel suffix because of the process of inversion described above.

The present tense of kteb is as follows:

I am writing: ka-ne-kteb

You are (masculine) writing: ka-te-kteb

You are (feminine) writing: ka-t-ketb-i

He's/it is writing: ka-ye-kteb

She is/it is writing: ka-te-kteb

We are writing: ka-n-ketb-u

You (plural) are writing: ka-t-ketb-u

They are writing: ka-y-ketb-u

The stem kteb turns into ketb before a vowel suffix because of the process of inversion described above. Between the prefix ka-n-, ka-t-, ka-y- and the stem kteb, an e appears but not between the prefix and the transformed stem ketb because of the same restriction that produces inversion.

In the north, "you are writing" is always ka-de-kteb regardless of who is addressed. This is also the case of de in de-kteb as northerners prefer to use de and southerners prefer te.

Instead of the prefix ka, some speakers prefer the use of ta (ta-ne-kteb "I am writing"). The coexistence of these two prefixes is from historic differences. In general, ka is more used in the north and ta in the south, some other prefixes like la, a, qa are less used. In some regions like in the east (Oujda), most speakers use no preverb (ne-kteb, te-kteb, y-kteb, etc.).

To form the future tense, the prefix ka-/ta- is removed and replaced with the prefix ġa-, ġad- or ġadi instead (e.g. ġa-ne-kteb "I will write", ġad-ketb-u (north) or ġadi t-ketb-u "You (plural) will write").

For the subjunctive and infinitive, the ka- is removed (bġit ne-kteb "I want to write", bġit te-kteb "I want 'you to write").

The imperative is conjugated with the suffixes of the present tense but without any prefixes or preverbs:

kteb Write! (masculine singular)

ketb-i Write! (feminine singular)

ketb-u Write! (plural)

One characteristic of Moroccan Arabic syntax, which it shares with other North African varieties as well as some southern Levantine dialect areas, is in the two-part negative verbal circumfix /ma-...-ʃi/. (In many regions, including Marrakech, the final /i/ vowel is not pronounced so it becomes /ma-...-ʃ/.)[30]

/ma-/ comes from the Classical Arabic negator /ma/. /-ʃi/ is a development of Classical /ʃajʔ/ "thing". The development of a circumfix is similar to the French circumfix ne ... pas in which ne comes from Latin non "not" and pas comes from Latin passus "step". (Originally, pas would have been used specifically with motion verbs, as in "I did not walk a step". It was generalised to other verbs.)

The negative circumfix surrounds the entire verbal composite, including direct and indirect object pronouns:

Future and interrogative sentences use the same /ma-...-ʃi/ circumfix (unlike, for example, in Egyptian Arabic). Also, unlike in Egyptian Arabic, there are no phonological changes to the verbal cluster as a result of adding the circumfix. In Egyptian Arabic, adding the circumfix can trigger stress shifting, vowel lengthening and shortening, elision when /ma-/ comes into contact with a vowel, addition or deletion of a short vowel, etc. However, they do not occur in Moroccan Arabic (MA):

Negative pronouns such as walu "nothing", ḥta ḥaja "nothing" and ḥta waḥed "nobody" can be added to the sentence without ši as a suffix:

Note that wellah ma-ne-kteb could be a response to a command to write kteb while wellah ma-ġa-ne-kteb could be an answer to a question like waš ġa-te-kteb? "Are you going to write?"

In the north, "'you are writing" is always ka-de-kteb regardless of who is addressed. It is also the case of de in de-kteb, as northerners prefer to use de and southerners prefer te.

Instead of the prefix ka, some speakers prefer the use of ta (ta-ne-kteb "I am writing"). The co-existence of these two prefixes is from historical differences. In general ka is more used in the north and ta in the south. In some regions like the east (Oujda), most speakers use no preverb:

Verbs in Moroccan Arabic are based on a consonantal root composed of three or four consonants. The set of consonants communicates the basic meaning of a verb. Changes to the vowels between the consonants, along with prefixes and/or suffixes, specify grammatical functions such as tense, person and number in addition to changes in the meaning of the verb that embody grammatical concepts such as causative, intensive, passive or reflexive.

Each particular lexical verb is specified by two stems, one used for the past tense and one used for non-past tenses, along with subjunctive and imperative moods. To the former stem, suffixes are added to mark the verb for person, number and gender. To the latter stem, a combination of prefixes and suffixes are added. (Very approximately, the prefixes specify the person and the suffixes indicate number and gender.) The third person masculine singular past tense form serves as the "dictionary form" used to identify a verb like the infinitive in English. (Arabic has no infinitive.) For example, the verb meaning "write" is often specified as kteb, which actually means "he wrote". In the paradigms below, a verb will be specified as kteb/ykteb (kteb means "he wrote" and ykteb means "he writes"), indicating the past stem (kteb-) and the non-past stem (also -kteb-, obtained by removing the prefix y-).

The verb classes in Moroccan Arabic are formed along two axes. The first or derivational axis (described as "form I", "form II", etc.) is used to specify grammatical concepts such as causative, intensive, passive or reflexive and mostly involves varying the consonants of a stem form. For example, from the root K-T-B "write" are derived form I kteb/ykteb "write", form II ketteb/yketteb "cause to write", form III kateb/ykateb "correspond with (someone)" etc. The second or weakness axis (described as "strong", "weak", "hollow", "doubled" or "assimilated") is determined by the specific consonants making up the root, especially whether a particular consonant is a "w" or " y", and mostly involves varying the nature and location of the vowels of a stem form. For example, so-called weak verbs have one of those two letters as the last root consonant, which is reflected in the stem as a final vowel instead of a final consonant (ṛma/yṛmi "throw" from Ṛ-M-Y). Meanwhile, hollow verbs are usually caused by one of those two letters as the middle root consonant, and the stems of such verbs have a full vowel (/a/, /i/ or /u/) before the final consonant, often along with only two consonants (žab/yžib "bring" from Ž-Y-B).

It is important to distinguish between strong, weak, etc. stems and strong, weak, etc. roots. For example, X-W-F is a hollow root, but the corresponding form II stem xuwwef/yxuwwef "frighten" is a strong stem:

In this section, all verb classes and their corresponding stems are listed, excluding the small number of irregular verbs described above. Verb roots are indicated schematically using capital letters to stand for consonants in the root:

Hence, the root F-M-L stands for all three-consonant roots, and F-S-T-L stands for all four-consonant roots. (Traditional Arabic grammar uses F-ʕ-L and F-ʕ-L-L, respectively, but the system used here appears in a number of grammars of spoken Arabic dialects and is probably less confusing for English speakers since the forms are easier to pronounce than those involving /ʕ/.)

The following table lists the prefixes and suffixes to be added to mark tense, person, number, gender and the stem form to which they are added. The forms involving a vowel-initial suffix and corresponding stem PAv or NPv are highlighted in silver. The forms involving a consonant-initial suffix and corresponding stem PAc are highlighted in gold. The forms involving no suffix and corresponding stem PA0 or NP0 are not highlighted.

The following table lists the verb classes along with the form of the past and non-past stems, active and passive participles, and verbal noun, in addition to an example verb for each class.

Notes:

Example: kteb/ykteb "write"

Some comments:

Example: kteb/ykteb "write": non-finite forms

Example: dker/ydker "mention"

This paradigm differs from kteb/ykteb in the following ways:

Reduction and assimilation occur as follows:

Examples:

Example: xrˤeʒ/yxrˤoʒ "go out"

Example: beddel/ybeddel "change"

Boldfaced forms indicate the primary differences from the corresponding forms of kteb, which apply to many classes of verbs in addition to form II strong:

Example: sˤaferˤ/ysˤaferˤ "travel"

The primary differences from the corresponding forms of beddel (shown in boldface) are:

Example: ttexleʕ/yttexleʕ "get scared"

Weak verbs have a W or Y as the last root consonant.

Example: nsa/ynsa "forget"

The primary differences from the corresponding forms of kteb (shown in ) are:

Example: rˤma/yrˤmi "throw"

This verb type is quite similar to the weak verb type nsa/ynsa. The primary differences are:

Verbs other than form I behave as follows in the non-past:

Examples:

Hollow have a W or Y as the middle root consonant. Note that for some forms (e.g. form II and form III), hollow verbs are conjugated as strong verbs (e.g. form II ʕeyyen/yʕeyyen "appoint" from ʕ-Y-N, form III ʒaweb/yʒaweb "answer" from ʒ-W-B).

Example: baʕ/ybiʕ "sell"

This verb works much like beddel/ybeddel "teach". Like all verbs whose stem begins with a single consonant, the prefixes differ in the following way from those of regular and weak form I verbs:

In addition, the past tense has two stems: beʕ- before consonant-initial suffixes (first and second person) and baʕ- elsewhere (third person).

Example: ʃaf/yʃuf "see"

This verb class is identical to verbs such as baʕ/ybiʕ except in having stem vowel /u/ in place of /i/.

Doubled verbs have the same consonant as middle and last root consonant, e.g. ɣabb/yiħebb "love" from Ħ-B-B.

Example: ħebb/yħebb "love"

This verb works much like baʕ/ybiʕ "sell". Like that class, it has two stems in the past, which are ħebbi- before consonant-initial suffixes (first and second person) and ħebb- elsewhere (third person). Note that /i-/ was borrowed from the weak verbs; the Classical Arabic equivalent form would be *ħabáb-, e.g. *ħabáb-t.

Some verbs have /o/ in the stem: koħħ/ykoħħ "cough".

As for the other forms:

"Doubly weak" verbs have more than one "weakness", typically a W or Y as both the second and third consonants. In Moroccan Arabic such verbs generally behave as normal weak verbs (e.g. ħya/yħya "live" from Ħ-Y-Y, quwwa/yquwwi "strengthen" from Q-W-Y, dawa/ydawi "treat, cure" from D-W-Y). This is not always the case in standard Arabic (cf. walā/yalī "follow" from W-L-Y).

The irregular verbs are as follows:

In general, Moroccan Arabic is one of the least conservative of all Arabic languages. Now, Moroccan Arabic continues to integrate new French words, even English ones due to its influence as the modern lingua franca, mainly technological and modern words. However, in recent years, constant exposure to Modern Standard Arabic on television and in print media and a certain desire among many Moroccans for a revitalization of an Arab identity has inspired many Moroccans to integrate words from Modern Standard Arabic, replacing their French, Spanish or otherwise non-Arabic counterparts, or even speaking in Modern Standard Arabic while keeping the Moroccan accent to sound less formal[31]

Though rarely written, Moroccan Arabic is currently undergoing an unexpected and pragmatic revival. It is now the preferred language in Moroccan chat rooms or for sending SMS, using Arabic Chat Alphabet composed of Latin letters supplemented with the numbers 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9 for coding specific Arabic sounds, as is the case with other Arabic speakers.

The language continues to evolve quickly as can be noted by consulting the Colin dictionary. Many words and idiomatic expressions recorded between 1921 and 1977 are now obsolete.

Some Moroccan Arabic speakers, in the parts of the country formerly ruled by France, practice code-switching with French. In parts of northern Morocco, such as in Tetouan and Tangier, it is common for code-switching to occur between Moroccan Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic, and Spanish, as Spain had previously controlled part of the region and continues to possess the territories of Ceuta and Melilla in North Africa bordering only Morocco. On the other hand, some Arab nationalist Moroccans generally attempt to avoid French and Spanish in their speech; consequently, their speech tends to resemble old Andalusian Arabic.

Although most Moroccan literature has traditionally been written in the classical Standard Arabic, the first record of a work of literature composed in Moroccan Arabic was Al-Kafif az-Zarhuni's al-Mala'ba, written in the Marinid period.[32]

There exists some poetry written in Moroccan Arabic like the Malhun. In the troubled and autocratic Morocco of the 1970s, Years of Lead, the Nass El Ghiwane band wrote lyrics in Moroccan Arabic that were very appealing to the youth even in other Maghreb countries.

Another interesting movement is the development of an original rap music scene, which explores new and innovative usages of the language.

Zajal, or improvised poetry, is mostly written in Moroccan Darija, and there have been at least dozens of Moroccan Darija poetry collections and anthologies published by Moroccan poets, such as Ahmed Lemsyeh[33] and Driss Amghar Mesnaoui. The later additionally wrote a novel trilogy in Moroccan Darija, a unique creation in this language, with the titles تاعروروت "Ta'arurut", عكاز الريح (the Wind's Crutch), and سعد البلدة (The Town's Luck).[34]

The first known scientific productions written in Moroccan Arabic were released on the Web in early 2010 by Moroccan teacher and physicist Farouk Taki El Merrakchi, three average-sized books dealing with physics and mathematics.[35]

There have been at least three newspapers in Moroccan Arabic; their aim was to bring information to people with a low level of education, or those simply interested in promoting the use of Moroccan Darija. From September 2006 to October 2010, Telquel Magazine had a Moroccan Arabic edition Nichane. From 2002 to 2006 there was also a free weekly newspaper that was entirely written in "standard" Moroccan Arabic: Khbar Bladna ('News of Our Country'). In Salé, the regional newspaper Al Amal, directed by Latifa Akherbach, started in 2005.[36]

The Moroccan online newspaper Goud or "ݣود" has much of its content written in Moroccan Arabic rather than Modern Standard Arabic. Its name "Goud" and its slogan "dima nishan" (ديما نيشان) are Moroccan Arabic expressions that mean almost the same thing "straightforward".[37]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)