Charles-Valentin Alkan[n 1][n 2] (French: [ʃaʁl valɑ̃tɛ̃ alkɑ̃]; 30 November 1813 – 29 March 1888) was a French composer and virtuoso pianist. At the height of his fame in the 1830s and 1840s he was, alongside his friends and colleagues Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt, among the leading pianists in Paris, a city in which he spent virtually his entire life.

Alkan earned many awards at the Conservatoire de Paris, which he entered before he was six. His career in the salons and concert halls of Paris was marked by his occasional long withdrawals from public performance, for personal reasons. Although he had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances in the Parisian artistic world, including Eugène Delacroix and George Sand, from 1848 he began to adopt a reclusive life style, while continuing with his compositions – virtually all of which are for the keyboard. During this period he published, among other works, his collections of large-scale studies in all the major keys (Op. 35) and all the minor keys (Op. 39). The latter includes his Symphony for Solo Piano (Op. 39, nos. 4–7) and Concerto for Solo Piano (Op. 39, nos. 8–10), which are often considered among his masterpieces and are of great musical and technical complexity. Alkan emerged from self-imposed retirement in the 1870s to give a series of recitals that were attended by a new generation of French musicians.

Alkan's attachment to his Jewish origins is displayed both in his life and his work. He was the first composer to incorporate Jewish melodies in art music. Fluent in Hebrew and Greek, he devoted much time to a complete new translation of the Bible into French. This work, like many of his musical compositions, is now lost. Alkan never married, but his presumed son Élie-Miriam Delaborde was, like Alkan, a virtuoso performer on both the piano and the pedal piano, and edited a number of the elder composer's works.

Following his death (which according to persistent but unfounded legend was caused by a falling bookcase), Alkan's music became neglected, supported by only a few musicians including Ferruccio Busoni, Egon Petri and Kaikhosru Sorabji. From the late 1960s onwards, led by Raymond Lewenthal and Ronald Smith, many pianists have recorded his music and brought it back into the repertoire.

Alkan was born Charles-Valentin Morhange on 30 November 1813 at 1 Rue de Braque in Paris to Alkan Morhange (1780–1855) and Julie Morhange, née Abraham.[9] Alkan Morhange was descended from a long-established Jewish Ashkenazic community in the region of Metz;[10] the village of Morhange is located about 30 miles (48 km) from the city of Metz. Charles-Valentin was the second of six children – one elder sister and four younger brothers; his birth certificate indicates that he was named after a neighbour who witnessed the birth.[11]

Alkan Morhange supported the family as a musician and later as the proprietor of a private music school in le Marais, in the Jewish quarter of Paris.[12] At an early age, Charles-Valentin and his siblings adopted their father's first name as their last (and were known by this during their studies at the Conservatoire de Paris and subsequent careers).[n 3] His brother Napoléon (1826–1906) became professor of solfège at the Conservatoire, his brother Maxim (1818–1897) had a career writing light music for Parisian theatres, and his sister, Céleste (1812–1897), was a singer.[14] His brother Ernest (1816–1876) was a professional flautist,[15] while the youngest brother Gustave (1827–1882) was to publish various dances for the piano.[16]

Alkan was a child prodigy.[17] He entered the Conservatoire de Paris at an unusually early age, and studied both piano and organ. The records of his auditions survive in the Archives Nationales in Paris. At his solfège audition on 3 July 1819, when he was just over 5 years 7 months, the examiners noted Alkan (who is referred to even at this early date as "Alkan (Valentin)", and whose age is given incorrectly as six-and-a-half) as "having a pretty little voice". The profession of Alkan Morhange is given as "music-paper ruler". At Charles-Valentin's piano audition on 6 October 1820, when he was nearly seven (and where he is named as "Alkan (Morhange) Valentin"), the examiners comment "This child has amazing abilities."[18]

Alkan became a favourite of his teacher at the Conservatoire, Joseph Zimmerman, who also taught Georges Bizet, César Franck, Charles Gounod, and Ambroise Thomas.[19] At the age of seven, Alkan won a first prize for solfège and in later years prizes in piano (1824), harmony (1827, as student of Victor Dourlen), and organ (1834).[20] At the age of seven-and-a-half he gave his first public performance, appearing as a violinist and playing an air and variations by Pierre Rode.[21] Alkan's Opus 1, a set of variations for piano based on a theme by Daniel Steibelt, dates from 1828, when he was 14 years old. At about this time he also undertook teaching duties at his father's school. Antoine Marmontel, one of Charles-Valentin's pupils there, who was later to become his bête noire, wrote of the school:

Young children, mostly Jewish, were given elementary musical instruction and also learnt the first rudiments of French grammar ... [There] I received a few lessons from the young Alkan, four years my senior ... I see once more ... that really parochial environment where the talent of Valentin Alkan was formed and where his hard-working youth blossomed ... It was like a preparatory school, a juvenile annexe of the Conservatoire.[22]

From about 1826 Alkan began to appear as a piano soloist in leading Parisian salons, including those of the Princesse de la Moskova (widow of Marshal Ney), and the Duchesse de Montebello. He was probably introduced to these venues by his teacher Zimmerman.[23] At the same time, Alkan Morhange arranged concerts featuring Charles-Valentin at public venues in Paris, in association with leading musicians including the sopranos Giuditta Pasta and Henriette Sontag, the cellist Auguste Franchomme and the violinist Lambert Massart, with whom Alkan gave concerts in a rare visit out of France to Brussels in 1827.[24] In 1829, at the age of 15, Alkan was appointed joint professor of solfège – among his pupils in this class a few years later was his brother Napoléon.[1] In this manner Alkan's musical career was launched well before the July Revolution of 1830, which initiated a period in which "keyboard virtuosity ... completely dominated professional music making" in the capital,[25] attracting from all over Europe pianists who, as Heinrich Heine wrote, invaded "like a plague of locusts swarming to pick Paris clean".[26] Alkan nonetheless continued his studies and in 1831 enrolled in the organ classes of François Benoist, from whom he may have learnt to appreciate the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, of whom Benoist was then one of the few French advocates.[27]

Throughout the early years of the July Monarchy, Alkan continued to teach and play at public concerts and in eminent social circles. He became a friend of many who were active in the world of the arts in Paris, including Franz Liszt (who had been based there since 1827), George Sand, and Victor Hugo. It is not clear exactly when he first met Frédéric Chopin, who arrived in Paris in September 1831.[28] In 1832 Alkan took the solo role in his first Concerto da camera for piano and strings at the Conservatoire. In the same year, aged 19, he was elected to the influential Société Académique des Enfants d'Apollon (Society of the Children of Apollo), whose members included Luigi Cherubini, Fromental Halévy, the conductor François Habeneck, and Liszt, who had been elected in 1824 at the age of twelve. Between 1833 and 1836 Alkan participated at many of the Society's concerts.[29][30] Alkan twice competed unsuccessfully for the Prix de Rome, in 1832 and again in 1834; the cantatas which he wrote for the competition, Hermann et Ketty and L'Entrée en loge, have remained unpublished and unperformed.[31]

.jpg/440px-Santiago_Masarnau_from_Retratos_de_don_Santiago_y_don_Vicente_Masarnau_(cropped).jpg)

In 1834 Alkan began his friendship with the Spanish musician Santiago Masarnau, which was to result in an extended and often intimate correspondence.[32][n 4] Like virtually all of Alkan's correspondence, this exchange is now one-sided; all of his papers (including his manuscripts and his extensive library) were either destroyed by Alkan himself, as is clear from his will,[33] or became lost after his death.[34] Later in 1834 Alkan made a visit to England, where he gave recitals and where the second Concerto da camera was performed in Bath by its dedicatee Henry Ibbot Field;[35] it was published in London together with some solo piano pieces. A letter to Masarnau[36] and a notice in a French journal that Alkan played in London with Moscheles and Cramer,[35] indicate that he returned to England in 1835. Later that year, Alkan, having found a place of retreat at Piscop outside Paris, completed his first truly original works for solo piano, the Twelve Caprices, published in 1837 as Opp. 12, 13, 15 and 16.[37] Op. 16, the Trois scherzi de bravoure, is dedicated to Masarnau. In January 1836, Liszt recommended Alkan for the post of Professor at the Geneva Conservatoire, which Alkan declined,[38] and in 1837 he wrote an enthusiastic review of Alkan's Op. 15 Caprices in the Revue et gazette musicale.[39]

From 1837, Alkan lived in the Square d'Orléans in Paris, which was inhabited by numerous celebrities of the time including Marie Taglioni, Alexandre Dumas, George Sand, and Chopin.[40] Chopin and Alkan were personal friends and often discussed musical topics, including a work on musical theory that Chopin proposed to write.[41] By 1838, at 25 years old, Alkan had reached a peak of his career.[42] He frequently gave recitals, his more mature works had begun to be published, and he often appeared in concerts with Liszt and Chopin. On 23 April 1837 Alkan took part in Liszt's farewell concert in Paris, together with the 14-year-old César Franck and the virtuoso Johann Peter Pixis.[43] On 3 March 1838, at a concert at the piano-maker Pape, Alkan played with Chopin, Zimmerman, and Chopin's pupil Adolphe Gutmann in a performance of Alkan's transcription, now lost, of two movements of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony for two pianos, eight hands.[44]

At this point, for a period which coincided with the birth and childhood of his natural son, Élie-Miriam Delaborde (1839–1913), Alkan withdrew into private study and composition for six years, returning to the concert platform only in 1844.[45][n 5] Alkan neither asserted nor denied his paternity of Delaborde, which, however, his contemporaries seemed to assume.[47] Marmontel wrote cryptically in a biography of Delaborde that "[his] birth is a page from a novel in the life of a great artist".[48] Alkan gave early piano lessons to Delaborde, who was to follow his natural father as a keyboard virtuoso.[49]

Alkan's return to the concert platform in 1844 was greeted with enthusiasm by critics, who noted the "admirable perfection" of his technique, and lauded him as "a model of science and inspiration", a "sensation" and an "explosion".[50] They also commented on the attending celebrities including Liszt, Chopin, Sand and Dumas. In the same year he published his piano étude Le chemin de fer, which critics, following Ronald Smith, believe to be the first representation in music of a steam engine.[51] Between 1844 and 1848 Alkan produced a series of virtuoso pieces, the 25 Préludes Op. 31 for piano or organ, and the sonata Op. 33 Les quatre âges.[52] Following an Alkan recital in 1848, the composer Giacomo Meyerbeer was so impressed that he invited the pianist, whom he considered "a most remarkable artist", to prepare the piano arrangement of the overture to his forthcoming opera, Le prophète. Meyerbeer heard and approved Alkan's arrangement of the overture for four hands (which Alkan played with his brother Napoléon) in 1849; published in 1850, it is the only record of the overture, which was scrapped during rehearsals at the Opéra.[53]

In 1848 Alkan was bitterly disappointed when the head of the Conservatoire, Daniel Auber, replaced the retiring Zimmerman with the mediocre Antoine Marmontel as head of the Conservatoire piano department, a position which Alkan had eagerly anticipated, and for which he had strongly lobbied with the support of Sand, Dumas, and many other leading figures.[54] A disgusted Alkan described the appointment in a letter to Sand as "the most incredible, the most shameful nomination";[55] and Delacroix noted in his journal: "By his confrontation with Auber, [Alkan] has been very put out and will doubtless continue to be so."[56] The upset arising from this incident may account for Alkan's reluctance to perform in public in the ensuing period. His withdrawal was also influenced by the death of Chopin; in 1850 he wrote to Masarnau "I have lost the strength to be of any economic or political use", and lamented "the death of poor Chopin, another blow which I felt deeply."[57] Chopin, on his deathbed in 1849, had indicated his respect for Alkan by bequeathing him his unfinished work on a piano method, intending him to complete it,[41] and after Chopin's death a number of his students transferred to Alkan.[58] After giving two concerts in 1853, Alkan withdrew, in spite of his fame and technical accomplishment, into virtual seclusion for some twenty years.[59]

Little is known of this period of Alkan's life, other than that apart from composing he was immersed in the study of the Bible and the Talmud. Throughout this period Alkan continued his correspondence with Ferdinand Hiller,[60] whom he had probably met in Paris in the 1830s,[61] and with Masarnau, from which some insights can be gained. It appears that Alkan completed a full translation into French, now lost, of both the Old Testament and the New Testament, from their original languages.[62] In 1865, he wrote to Hiller: "Having translated a good deal of the Apocrypha, I'm now onto the second Gospel which I am translating from the Syriac ... In starting to translate the New Testament, I was suddenly struck by a singular idea – that you have to be Jewish to be able to do it."[63]

Despite his seclusion from society, this period saw the composition and publication of many of Alkan's major piano works, including the Douze études dans tous les tons mineurs, Op. 39 (1857), the Sonatine, Op. 61 (1861), the 49 Esquisses, Op. 63 (1861), and the five collections of Chants (1857–1872), as well as the Sonate de concert for cello and piano, Op. 47 (1856). These did not pass unremarked; Hans von Bülow, for example, gave a laudatory review of the Op. 35 Études in the Neue Berliner Musikzeitung in 1857, the year in which they were published in Berlin, commenting that "Alkan is unquestionably the most eminent representative of the modern piano school at Paris. The virtuoso's disinclination to travel, and his firm reputation as a teacher, explain why, at present, so little attention has been given to his work in Germany."[64]

From the early 1850s Alkan began to turn his attention seriously to the pedal piano (pédalier). Alkan gave his first public performances on the pédalier to great critical acclaim in 1852.[65] From 1859 onwards he began to publish pieces designated as "for organ or piano à pédalier".[66]

It is not clear why, in 1873, Alkan decided to emerge from his self-imposed obscurity to give a series of six Petits Concerts at the Érard piano showrooms. It may have been associated with the developing career of Delaborde, who, returning to Paris in 1867, soon became a concert fixture, including in his recitals many works by his father, and who was at the end of 1872 given the appointment that had escaped Alkan himself, Professor at the Conservatoire.[67] The success of the Petits Concerts led to them becoming an annual event (with occasional interruptions caused by Alkan's health) until 1880 or possibly beyond.[68] The Petits Concerts featured music not only by Alkan but of his favourite composers from Bach onwards, played on both the piano and the pédalier, and occasionally with the participation of another instrumentalist or singer. He was assisted in these concerts by his siblings, and by other musicians including Delaborde, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Auguste Franchomme.[69]

Those encountering Alkan at this phase included the young Vincent d'Indy, who recalled Alkan's "skinny, hooked fingers" playing Bach on an Érard pedal piano: "I listened, riveted to the spot by the expressive, crystal-clear playing." Alkan later played Beethoven's Op. 110 sonata, of which d'Indy said: "What happened to the great Beethovenian poem ... I couldn't begin to describe – above all in the Arioso and the Fugue, where the melody, penetrating the mystery of Death itself, climbs up to a blaze of light, affected me with an excess of enthusiasm such as I have never experienced since. This was not Liszt—perhaps less perfect, technically—but it had greater intimacy and was more humanly moving ..."[70]

The biographer of Chopin, Frederick Niecks, sought Alkan for his recollections in 1880 but was sternly denied access by Alkan's concierge – "To my ... enquiry when he could be found at home, the reply was a ... decisive 'Never'." However, a few days later he found Alkan at Érard's, and Niecks writes of their meeting that "his reception of me was not merely polite but most friendly."[71]

According to his death certificate, Alkan died in Paris on 29 March 1888 at the age of 74.[72] Alkan was buried on 1 April (Easter Sunday) in the Jewish section of Montmartre Cemetery, Paris,[73] not far from the tomb of his contemporary Fromental Halévy; his sister Céleste was later buried in the same tomb.[74]

For many years it was believed that Alkan met his death when a bookcase toppled over and fell on him as he reached for a volume of the Talmud from a high shelf. This tale, which was circulated by the pianist Isidor Philipp,[75] is dismissed by Hugh Macdonald, who reports the discovery of a contemporary letter by one of his pupils explaining that Alkan had been found prostrate in his kitchen, under a porte-parapluie (a heavy coat/umbrella rack), after his concierge heard his moaning. He had possibly fainted, bringing it down on himself while grabbing out for support. He was reportedly carried to his bedroom and died later that evening.[76] The story of the bookcase may have its roots in a legend told of Aryeh Leib ben Asher, rabbi of Metz, the town from which Alkan's family originated.[77]

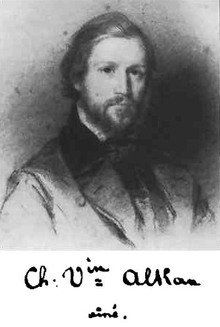

Alkan was described by Marmontel (who refers to "a regrettable misunderstanding at a moment of our careers in 1848"), as follows:

We will not give the portrait of Valentin Alkan from the rear, as in some photographs we have seen. His intelligent and original physiognomy deserves to be taken in profile or head-on. The head is strong; the deep forehead is that of a thinker; the mouth large and smiling, the nose regular; the years have whitened the beard and hair ... the gaze fine, a little mocking. His stooped walk, his puritan comportment, give him the look of an Anglican minister or a rabbi – for which he has the abilities.[78]

Alkan was not always remote or aloof. Chopin describes, in a letter to a friend, visiting the theatre with Alkan in 1847 to see the comedian Arnal: "[Arnal] tells the audience how he was desperate to pee in a train, but couldn't get to a toilet before they stopped at Orléans. There wasn't a single vulgar word in what he said, but everyone understood and split their sides laughing."[79] Hugh Macdonald notes that Alkan "particularly enjoyed the patronage of Russian aristocratic ladies, 'des dames très parfumées et froufroutantes [highly perfumed and frilled ladies]', as Isidore Philipp described them."[80]

Alkan's aversion to socialising and publicity, especially following 1850, appeared to be self-willed. Liszt is reported to have commented to the Danish pianist Frits Hartvigson that "Alkan possessed the finest technique he had ever known, but preferred the life of a recluse."[81]

Alkan's later correspondence contains many despairing comments. In a letter of about 1861 he wrote to Hiller:

I'm becoming daily more and more misanthropic and misogynous ... nothing worthwhile, good or useful to do ... no one to devote myself to. My situation makes me horridly sad and wretched. Even musical production has lost its attraction for me for I can't see the point or goal."[82]

This spirit of anomie may have led him to reject requests in the 1860s to play in public, or to allow performances of his orchestral compositions.[83] However, it should not be ignored that he was writing similarly frantic self-analyses in his letters of the early 1830s to Masarnau.[84]

Hugh MacDonald writes that "Alkan's enigmatic character is reflected in his music – he dressed in a severe, old-fashioned, somewhat clerical manner – only in black – discouraged visitors and went out rarely – he had few friends – was nervous in public and was pathologically worried about his health, even though it was good". Ronald Smith writes that "Alkan's characteristics, exacerbated no doubt by his isolation, are carried to the edge of fanaticism, and at the heart of Alkan's creativity there is also fierce obsessional control; his obsession with a specific idea can border on the pathological."[85]

Jack Gibbons writes of Alkan's personality: "Alkan was an intelligent, lively, humorous and warm person (all characteristics which feature strongly in his music) whose only crime seems to have been having a vivid imagination, and whose occasional eccentricities (mild when compared with the behaviour of other 'highly-strung' artistes!) stemmed mainly from his hypersensitive nature."[86] Macdonald, however, suggests that "Alkan was a man of profoundly conservative ideas, whose lifestyle, manner of dress, and belief in the traditions of historic music, set him apart from other musicians and the world at large."[87]

Alkan grew up in a religiously observant Jewish household. His grandfather Marix Morhange had been a printer of the Talmud in Metz, and was probably a melamed (Hebrew teacher) in the Jewish congregation at Paris.[88] Alkan's widespread reputation as a student of the Old Testament and religion, and the high quality of his Hebrew handwriting[89] testify to his knowledge of the religion, and some of his habits indicate that he practised at least some of its obligations, such as maintaining the laws of kashrut.[90] Alkan was regarded by the Paris Consistory, the central Jewish organisation of the city, as an authority on Jewish music. In 1845 he assisted the Consistory in evaluating the musical ability of Samuel Naumbourg, who was subsequently appointed as hazzan (cantor) of the main Paris synagogue;[91] and he later contributed choral pieces in each of Naumbourg's collections of synagogue music (1847 and 1856).[92] Alkan was appointed organist at the Synagogue de Nazareth in 1851, although he resigned the post almost immediately for "artistic reasons".[93]

Alkan's Op. 31 set of Préludes includes a number of pieces based on Jewish subjects, including some titled Prière (Prayer), one preceded by a quote from the Song of Songs, and another titled Ancienne mélodie de la synagogue (Old synagogue melody).[94] The collection is believed to be "the first publication of art music specifically to deploy Jewish themes and ideas."[95] Alkan's three settings of synagogue melodies, prepared for his former pupil Zina de Mansouroff, are further examples of his interest in Jewish music; Kessous Dreyfuss provides a detailed analysis of these works and their origins.[96] Other works evidencing this interest include no. 7 of his Op. 66. 11 Grands préludes et 1 Transcription (1866), entitled "Alla giudesca" and marked "con divozione", a parody of excessive hazzanic practice;[97] and the slow movement of the cello sonata Op. 47 (1857), which is prefaced by a quotation from the Old Testament prophet Micah and uses melodic tropes derived from the cantillation of the haftarah in the synagogue.[74]

The inventory of Alkan's apartment made after his death indicates over 75 volumes in Hebrew or related to Judaism, left to his brother Napoléon (as well as 36 volumes of music manuscript).[98] These are all lost.[99] Bequests in his will to the Conservatoire to found prizes for composition of cantatas on Old Testament themes[n 6] and for performance on the pedal-piano, and to a Jewish charity for the training of apprentices, were refused by the beneficiaries.[101]

Brigitte François-Sappey points out the frequency with which Alkan has been compared to Berlioz, both by his contemporaries and later. She mentions that Hans von Bülow called him "the Berlioz of the piano", while Schumann, in criticising the Op. 15 Romances, claimed that Alkan merely "imitated Berlioz on the piano." She further notes that Ferruccio Busoni repeated the comparison with Berlioz in a draft (but unpublished) monograph, while Kaikhosru Sorabji commented that Alkan's Op. 61 Sonatine was like "a Beethoven sonata written by Berlioz".[102] Berlioz was ten years older than Alkan, but did not attend the Conservatoire until 1826. The two were acquainted, and were perhaps both influenced by the unusual ideas and style of Anton Reicha who taught at the Conservatoire from 1818 to 1836, and by the sonorities of the composers of the period of the French Revolution.[103] They both created individual, indeed, idiosyncratic sound-worlds in their music; there are, however, major differences between them. Alkan, unlike Berlioz, remained closely dedicated to the German musical tradition; his style and composition were heavily determined by his pianism, whereas Berlioz could hardly play at the keyboard and wrote almost nothing for piano solo. Alkan's works therefore also include miniatures and (among his early works) salon music, genres which Berlioz avoided.[104]

Alkan's attachment to the music of his predecessors is demonstrated throughout his career, from his arrangements for keyboard of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony (1838), and of the minuet of Mozart's 40th Symphony (1844), through the sets Souvenirs des concerts du Conservatoire (1847 and 1861) and the set Souvenirs de musique de chambre (1862), which include transcriptions of music by Mozart, Beethoven, J. S. Bach, Haydn, Gluck, and others.[105] In this context should be mentioned Alkan's extensive cadenza for Beethoven's 3rd Piano Concerto (1860), which includes quotes from the finale of Beethoven's 5th Symphony.[106] Alkan's transcriptions, together with original music of Bach, Beethoven, Handel, Mendelssohn, Couperin and Rameau, were frequently played during the series of Petits Concerts given by Alkan at Erard.[107]

As regards the music of his own time, Alkan was unenthusiastic, or at any rate detached. He commented to Hiller that "Wagner is not a musician, he is a disease."[108] While he admired Berlioz's talent, he did not enjoy his music.[109] At the Petits Concerts, little more recent than Mendelssohn and Chopin (both of whom had died around 25 years before the series of concerts was initiated) was played, except for Alkan's own works and occasionally some by his favourites such as Saint-Saëns.[110]

"Like ... Chopin", writes pianist and academic Kenneth Hamilton, "Alkan's musical output was centred almost exclusively on the piano".[111] Some of his music requires extreme technical virtuosity, clearly reflecting his own abilities, often calling for great velocity, enormous leaps at speed, long stretches of fast repeated notes, and the maintenance of widely spaced contrapuntal lines.[112] The illustration (right) from the Grande sonate is analysed by Smith as "six parts in invertible counterpoint, plus two extra voices and three doublings – eleven parts in all."[113] Some typical musical devices, such as a sudden explosive final chord following a quiet passage, were established at an early stage in Alkan's compositions.[114]

Macdonald suggests that

unlike Wagner, Alkan did not seek to refashion the world through opera; nor, like Berlioz, to dazzle the crowds by putting orchestral music at the service of literary expression; nor even, as with Chopin or Liszt, to extend the field of harmonic idiom. Armed with his key instrument, the piano, he sought incessantly to transcend its inherent technical limits, remaining apparently insensible to the restrictions which had withheld more restrained composers.[115]

However, not all of Alkan's music is either lengthy or technically difficult; for example, many of the Op. 31 Préludes and of the set of Esquisses, Op. 63.[116]

Moreover, in terms of structure, Alkan in his compositions sticks to traditional musical forms, although he often took them to extremes, as he did with piano technique. The study Op. 39, no. 8 (the first movement of the Concerto for solo piano) takes almost half an hour in performance. Describing this "gigantic" piece, Ronald Smith comments that it convinces for the same reasons as does the music of the classical masters; "the underlying unity of its principal themes, and a key structure that is basically simple and sound."[117]

The Chant Op. 38, no. 2, entitled Fa, repeats the note of its title incessantly (in total 414 times) against shifting harmonies which make it "cut ... into the texture with the ruthless precision of a laser beam."[118] In modelling his five sets of Chants on the first book of Mendelssohn's Songs Without Words, Alkan ensured that the pieces in each of his sets followed precisely the same key signatures, and even the moods, of the original.[119] Alkan was rigorous in his enharmonic spelling, occasionally modulating to keys containing double-sharps or double-flats, so pianists are occasionally required to come to terms with unusual keys such as E♯ major, the enharmonic equivalent to F major, and the occasional triple-sharp.[n 7]

Alkan's earliest works indicate, according to Smith, that in his early teens he "was a formidable musician but as yet ... industrious rather than ... creative".[121] Only with his 12 Caprices (Opp.12–13 and 15–16, 1837) did his compositions begin to attract serious critical attention. The Op. 15 set, Souvenirs: Trois morceaux dans le genre pathétique, dedicated to Liszt, contains Le vent (The Wind), which was at one time the only piece by the composer to figure regularly in recitals.[n 8] These works, however, did not meet with the approval of Robert Schumann, who wrote: "One is startled by such false, such unnatural art ... the last [piece, titled Morte (Death), is] a crabbed waste, overgrown with brush and weeds ... nothing is to be found but black on black".[124] Ronald Smith, however, finds in this latter work, which cites the Dies Irae theme also used by Berlioz, Liszt and others, foreshadowings of Maurice Ravel, Modest Mussorgsky and Charles Ives.[125] Schumann did, however, respond positively to the pieces of Les mois (originally part published as Op. 8 in 1838, later published as a complete set in 1840 as Op. 74):[n 9] "[Here] we find such an excellent jest on operatic music in no. 6 [L'Opéra] that a better one could scarcely be imagined ... The composer ... well understands the rarer effects of his instrument."[126] Alkan's technical mastery of the keyboard was asserted by the publication in 1838 of the Trois grandes études (originally without opus number, later republished as Op. 76), the first for the left hand alone, the second for the right hand alone, the third for both hands; and all of great difficulty, described by Smith as "a peak of pianistic transcendentalism".[127] This is perhaps the earliest example of writing for a single hand as "an entity in its own right, capable of covering all registers of the piano, of rendering itself as accompanied soloist or polyphonist."[128]

Alkan's large scale Duo (in effect a sonata) Op. 21 for violin and piano (dedicated to Chrétien Urhan) and his Piano Trio Op. 30 appeared in 1841. Apart from these, Alkan published only a few minor works between 1840 and 1844, after which a series of virtuoso works was issued, many of which he had played at his successful recitals at Érard and elsewhere;[129] these included the Marche funèbre (Op. 26), the Marche triomphale (Op. 27) and Le chemin de fer (also published, separately, as Op. 27). In 1847 appeared the Op. 31 Préludes (in all major and minor keys, with an extra closing piece returning to C major) and his first large-scale unified piano work, the Grande sonate Les quatre âges (Op. 33). The sonata is structurally innovative in two ways; each movement is slower than its predecessor, and the work anticipates the practice of progressive tonality, beginning in D major and ending in G♯ minor. Dedicated to Alkan Morhange, the sonata depicts in its successive movements its 'hero' at the ages of 20 (optimistic), 30 ("Quasi-Faust", impassioned and fatalistic), 40 (domesticated) and 50 (suffering: the movement is prefaced by a quotation from Aeschylus's Prometheus Unbound).[130] In 1848 followed Alkan's set of 12 études dans tous les tons majeurs Op. 35, whose substantial pieces range in mood from the hectic Allegro barbaro (no. 5) and the intense Chant d'amour-Chant de mort (Song of Love – Song of Death) (no. 10) to the descriptive and picturesque L'incendie au village voisin (The Fire in the Next Village) (no. 7).[131]

A number of Alkan's compositions from this period were never performed and have been lost. Among the missing works are some string sextets and a full-scale orchestral symphony in B minor, which was described in an article in 1846 by the critic Léon Kreutzer, to whom Alkan had shown the score.[132] Kreutzer noted that the introductory adagio of the symphony was headed "by Hebrew characters in red ink ... This is no less than the verse from Genesis: And God said, Let there be light: and there was light." Kreutzer opined that, set beside Alkan's conception, Joseph Haydn's Creation was a "mere candle (lampion)."[133] A further missing work is a one-act opera, mentioned frequently in the French musical press of 1846–7 as being shortly to be produced at the Opéra-Comique, which however never materialized. Alkan also referred to this work in a letter of 1847 to the musicologist François-Joseph Fétis, stating that it had been written "a few years ago." Its subject, title and librettist remain unknown.[134]

During his twenty-year absence from the public between 1853 and 1873 Alkan produced many of his most notable compositions, although there is a ten-year gap between publication of the Op. 35 studies and that of his next group of piano works in 1856 and 1857. Of these, undoubtedly the most significant was the enormous Opus 39 collection of twelve studies in all the minor keys, which contains the Symphony for Solo Piano (numbers four, five, six and seven), and the Concerto for Solo Piano (numbers eight, nine and ten).[n 10] The Concerto takes nearly an hour in performance. Number twelve of Op. 39 is a set of variations, Le festin d'Ésope (Aesop's Feast). The other components of Op. 39 are of a similar stature. Smith describes Op. 39 as a whole as "a towering achievement, gathering ... the most complete manifestation of Alkan's many-sided genius: its dark passion, its vital rhythmic drive, its pungent harmony, its occasionally outrageous humour, and, above all, its uncompromising piano writing."[135]

In the same year appeared the Sonate de concert, Op. 47, for cello and piano, "among the most difficult and ambitious in the romantic repertoire ... anticipating Mahler in its juxtaposition of the sublime and the trivial". In the opinion of the musicologist Brigitte François-Sappey, its four movements again show an anticipation of progressive tonality, each ascending by a major third.[136] Other anticipations of Mahler (who was born in 1860) can be found in the two "military" Op. 50 piano studies of 1859 Capriccio alla soldatesca and Le tambour bat aux champs (The drum beats the retreat),[137] as well as in certain of the miniatures of the 1861 Esquisses, Op. 63.[138] The bizarre and unclassifiable Marcia funebre, sulla morte d'un Pappagallo (Funeral march on the death of a parrot, 1859), for three oboes, bassoon and voices, described by Kenneth Hamilton as "Monty-Pythonesque",[139] is also of this period.

The Esquisses of 1861 are a set of highly varied miniatures, ranging from the tiny 18-bar no. 4, Les cloches (The Bells), to the strident tone clusters of no. 45, Les diablotins (The Imps), and closing with a further evocation of church bells in no. 49, Laus Deo (Praise God). Like the earlier Preludes and the two sets of Etudes, they span all the major and minor keys (in this case covering each key twice, with an extra piece in C major).[140] They were preceded in publication by Alkan's deceptively titled Sonatine, Op. 61, in 'classical' format, but a work of "ruthless economy [which] although it plays for less than twenty minutes ... is in every way a major work."[141]

Two of Alkan's substantial works from this period are musical paraphrases of literary works. Salut, cendre du pauvre, Op. 45 (1856), follows a section of the poem La Mélancolie by Gabriel-Marie Legouvé;[142] while Super flumina Babylonis, Op. 52 (1859), is a blow-by-blow recreation in music of the emotions and prophecies of Psalm 137 ("By the waters of Babylon ..."). This piece is prefaced by a French version of the psalm which is believed to be the sole remnant of Alkan's Bible translation.[143] Alkan's lyrical side was displayed in this period by the five sets of Chants inspired by Mendelssohn (Opp. 38, 65, 67, and 70), which appeared between 1857 and 1872, as well as by a number of minor pieces, such as three Nocturnes, Opp. 57 and 60bis (1859).

Alkan's publications for organ or pédalier commenced with his Benedictus, Op. 54 (1859). In the same year he published a set of very spare and simple preludes in the eight Gregorian modes (1859, without opus number), which, in Smith's opinion, "seem to stand outside the barriers of time and space", and which he believes reveal "Alkan's essential spiritual modesty."[144] These were followed by pieces such as the 13 Prières (Prayers), Op. 64 (1865), and the Impromptu sur le Choral de Luther "Un fort rempart est notre Dieu" , Op. 69 (1866).[145] Alkan also issued a book of 12 studies for the pedalboard alone (no opus number, 1866) and the Bombardo-carillon for pedalboard duet (four feet) of 1872.[146]

Alkan's return to the concert platform at his Petits Concerts, however, marked the end of his publications; his final work to be issued was the Toccatina, Op. 75, in 1872.[147][n 11]

Alkan had few followers;[n 12] however, he had important admirers, including Liszt, Anton Rubinstein, Franck, and, in the early twentieth century, Busoni, Petri and Sorabji. Rubinstein dedicated his fifth piano concerto to him,[149] and Franck dedicated to Alkan his Grand pièce symphonique op. 17 for organ.[150] Busoni ranked Alkan with Liszt, Chopin, Schumann and Brahms as one of the five greatest composers for the piano since Beethoven.[151] Isidor Philipp and Delaborde edited new printings of his works in the early 1900s.[152] In the first half of the twentieth century, when Alkan's name was still obscure, Busoni and Petri included his works in their performances.[153] Sorabji published an article on Alkan in his 1932 book Around Music;[154] he promoted Alkan's music in his reviews and criticism, and his Sixth Symphony for Piano (Symphonia claviensis) (1975–76), includes a section entitled Quasi Alkan.[155][156] The English composer and writer Bernard van Dieren praised Alkan in an essay in his 1935 book, Down Among the Dead Men,[157] and the composer Humphrey Searle also called for a revival of his music in a 1937 essay.[158] The pianist and writer Charles Rosen however considered Alkan "a minor figure", whose only music of interest comes after 1850 as an extension of Liszt's techniques and of "the operatic techniques of Meyerbeer."[159]

For much of the 20th century, Alkan's work remained in obscurity, but from the 1960s onwards it was steadily revived. Raymond Lewenthal gave a pioneering extended broadcast on Alkan on WBAI radio in New York in 1963,[160] and later included Alkan's music in recitals and recordings. The English pianist Ronald Smith championed Alkan's music through performances, recordings, a biography and the Alkan Society of which he was president for many years.[161] Works by Alkan have also been recorded by Jack Gibbons, Marc-André Hamelin, Mark Latimer, John Ogdon, Hüseyin Sermet and Mark Viner, among many others.[162] Ronald Stevenson composed a piano piece Festin d'Alkan (referring to Alkan's Op. 39, no. 12)[163] and the composer Michael Finnissy has also written piano pieces referring to Alkan, e.g. Alkan-Paganini, no. 5 of The History of Photography in Sound.[164] Marc-André Hamelin's Étude No. IV is a moto perpetuo study combining themes from Alkan's Symphony, Op. 39, no. 7, and Alkan's own perpetual motion étude, Op. 76, no. 3. It is dedicated to Averil Kovacs and François Luguenot, respectively activists in the English and French Alkan Societies. As Hamelin writes in his preface to this étude, the idea to combine these came from the composer Alistair Hinton, the finale of whose Piano Sonata No. 5 (1994–95) includes a substantial section entitled "Alkanique".[165]

Alkan's compositions for organ have been among the last of his works to be brought back to the repertoire.[166] As to Alkan's pedal-piano works, due to a recent revival of the instrument, they are once again being performed as originally intended (rather than on an organ), such as by Italian pedal-pianist Roberto Prosseda,[167] and recordings of Alkan on the pedal piano have been made by Jean Dubé[168] and Olivier Latry.[169]

This list comprises a selection of some premiere and other recordings by musicians who have become closely associated with Alkan's works. A comprehensive discography is available at the Alkan Society website.[170]

Notes

Citations

Sources

Archives

Musical editions

Journals dedicated to Alkan

Books and articles