The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World's Fair, was an international exposition held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from April 30 to December 1, 1904. Local, state, and federal funds totaling $15 million (equivalent to $509 million in 2023)[1] were used to finance the event. More than 60 countries and 43 of the then-45 American states maintained exhibition spaces at the fair, which was attended by nearly 19.7 million people.

Historians generally emphasize the prominence of the themes of race and imperialism, and the fair's long-lasting impact on intellectuals in the fields of history, art history, architecture and anthropology. From the point of view of the memory of the average person who attended the fair, it primarily promoted entertainment, consumer goods and popular culture.[2] The monumental Greco-Roman architecture of this and other fairs of the era did much to influence permanent new buildings and master plans of major cities.

In 1904, St. Louis hosted a World's Fair to celebrate the centennial of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. The idea for such a commemorative event seems to have emerged early in 1898, with Kansas City and St. Louis initially presented as potential hosts for a fair based on their central location within the territory encompassed by the 1803 land annexation.[5]

The exhibition was grand in scale and lengthy in preparation, with an initial $5 million committed by the city of St. Louis through the sale of city bonds, authorized by the Missouri state legislature in April 1899.[6] An additional $5 million was generated through private donations by interested citizens and businesses from around Missouri, a fundraising target reached in January 1901.[7] The final installment of $5 million of the exposition's $15 million capitalization came in the form of earmarked funds that were part of a congressional appropriations bill passed at the end of May 1900.[8] The fundraising mission was aided by the active support of President of the United States William McKinley, which was won by organizers in a February 1899 White House visit.[9]

While initially conceived as a centennial celebration to be held in 1903, the actual opening of the St. Louis exposition was delayed until April 30, 1904, to allow for full-scale participation by more states and foreign countries. The exposition operated until December 1, 1904. During the year of the fair, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition supplanted the annual St. Louis Exposition of agricultural, trade, and scientific exhibitions which had been held in the city since the 1880s.

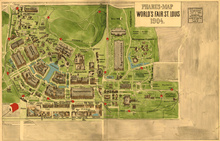

The fair's 1,200-acre (4.9 km2; 1.9 sq mi) site, designed by George Kessler,[10] was located at the present-day grounds of Forest Park and on the campus of Washington University, and was the largest fair (in area) to date. There were over 1,500 buildings, connected by some 75 miles (121 km) of roads and walkways. It was said to be impossible to give even a hurried glance at everything in less than a week. The Palace of Agriculture alone covered some 20 acres (81,000 m2).

Exhibits were staged by approximately 50 foreign nations, the United States government, and 43 of the then-45 U.S. states. These featured industries, cities, private organizations and corporations, theater troupes, and music schools. There were also over 50 concession-type amusements found on "The Pike"; they provided educational and scientific displays, exhibits and imaginary 'travel' to distant lands, history and local boosterism (including Louis Wollbrinck's "Old St. Louis") and pure entertainment.

Over 19 million[11] individuals were in attendance at the fair.

Aspects that attracted visitors included the buildings and architecture, new foods, popular music, and exotic people on display. American culture was showcased at the fair especially regarding innovations in communication, medicine, and transportation.[12]

George Kessler, who designed many urban parks in Texas and the Midwest, created the master design for the Fair.

A popular myth says that Frederick Law Olmsted, who had died the year before the Fair, designed the park and fair grounds. There are several reasons for this confusion. First, Kessler in his twenties had worked briefly for Olmsted as a Central Park gardener. Second, Olmsted was involved with Forest Park in Queens, New York. Third, Olmsted had planned the renovations in 1897 to the Missouri Botanical Garden several blocks to the southeast of the park.[13] Finally, Olmsted's sons advised Washington University on integrating the campus with the park across the street.

In 1901 the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Corporation selected prominent St. Louis architect Isaac S. Taylor as the Chairman of the Architectural Commission and Director of Works for the fair, supervising the overall design and construction. Taylor quickly appointed Emmanuel Louis Masqueray to be his Chief of Design. In the position for three years, Masqueray designed the following Fair buildings: Palace of Agriculture, the Cascades and Colonnades, Palace of Forestry, Fish, and Game, Palace of Horticulture and Palace of Transportation, all of which were widely emulated in civic projects across the United States as part of the City Beautiful movement. Masqueray resigned shortly after the Fair opened in 1904, having been invited by Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul, Minnesota to design a new cathedral for the city.[14][failed verification] The Palace of Electricity was designed by Messrs. Walker & Kimball, of Omaha, Nebraska. It covered 9 acres (3.6 ha) and cost over $400,000 (equivalent to more than $13.6 million in 2023).[1] Crowning the great towers were heroic groups of statuary typifying the various attributes of electricity.[15]

Florence Hayward, a successful freelance writer in St. Louis in the 1900s, was determined to play a role in the World's Fair. She negotiated a position on the otherwise all-male Board of Commissioners. Hayward learned that one of the potential contractors for the fair was not reputable and warned the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company (LPEC). In exchange for this information, she requested an appointment as roving commissioner to Europe.

Former Mayor of St. Louis and Governor of Missouri David R. Francis, LPEC president, made the appointment and allowed Hayward to travel overseas to promote the fair, especially to women. The fair also had a Board of Lady Managers (BLM) who felt they had jurisdiction over women's activities at the fair and objected to Hayward's appointment without their knowledge. Despite this, Hayward set out for England in 1902. Hayward's most notable contribution to the fair was acquiring gifts Queen Victoria received for her Golden Jubilee and other historical items, including manuscripts from the Vatican. These items were all to be shown in exhibits at the fair.

Pleased with her success in Europe, Francis put her in charge of historical exhibits in the anthropology division, which had originally been assigned to Pierre Chouteau III. Despite being the only woman on the Board of Commissioners, creating successful anthropological exhibits, publicizing the fair, and acquiring significant exhibit items, Hayward's role in the fair was not acknowledged. When Francis published a history of the fair in 1913, he did not mention Hayward's contributions and she never forgave the slight.[16]

Expositions are the timekeepers of progress. They record the world's advancement. They stimulate the energy, enterprise, and intellect of the people; and quicken human genius. They go into the home. They broaden and brighten the daily life of the people. They open mighty storehouses of information to the student.

— President William McKinley at the 1901 World's Fair

_(page_12_crop).jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

Many of the inventions displayed were precursors to items which have become an integral part of today's culture. Novel applications of electricity and light waves for communication and medical use were displayed in the Palace of Electricity.[17] According to an article he wrote for Harper's Weekly, W.E. Goldsborough, the Chief of the Department of Electricity for the Fair, wished to educate the public and dispel the misconceptions about electricity which many common people believed.[18] New and updated methods of transportation also showcased at the World's Fair in the Palace of Transportation would come to revolutionize transportation for the modern day.[17][19]

Wireless telephone – The "wireless telephony" unit or "radiophone" was invented by Alexander Graham Bell and installed at the St. Louis World Fair.[17][18] This radiophone comprised a sound-light transmitter and a light-sound receiver,[20] as an apparatus in the Palace of Electricity transmitted music or speech to a receiver in the courtyard. Visitors heard the transmission when holding the cordless receiver to the ear. It developed into the radio and telephone.[21]

Early fax machine – The telautograph was invented in 1888 by American scientist Elisha Gray, who contested Alexander Graham Bell's invention of the telephone.[22] A person wrote on one end of the telautograph, which electrically communicated with the receiving pen to recreate drawings on paper. In 1900, assistant Foster Ritchie improved the device to display at the 1904 World's Fair and market for the next thirty years.[23] This developed into the fax machine.

Finsen light – The Finsen light, invented by Niels Ryberg Finsen, treated tuberculosis luposa. Finsen received the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology in 1903.[24] This pioneered phototherapy.[24]

X-ray machine – The X-ray machine was launched at the 1904 World's Fair. German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays studying electrification of low pressure gas.[25] He X-rayed his wife's hand, capturing her bones and wedding ring to show colleagues. Thomas Edison and assistant Clarence Dally recreated the machine. Dally failed to test another X-ray machine at the 1901 World's Fair after President McKinley was assassinated.[26] A perfected X-ray machine was successfully exhibited at the 1904 World's Fair. X-rays are now commonplace in hospitals and airports.[27]

Infant incubator – Although infant incubators were invented in the year 1888 by Drs. Alan M. Thomas and William Champion, adoption was not immediate. To advertise the benefits, incubators containing preterm babies were displayed at the 1897, 1898, 1901, and 1904 World Fairs.[28] These provided immunocompromised neonates a sanitary environment. Each incubator comprised an airtight glass box with a metal frame. Hot forced air thermoregulated the container. Newspapers advertised the incubators with "lives are being preserved by this wonderful method."[29] During the 1904 World Fair, E. M. Bayliss exhibited these devices on The Pike where approximately ten nurses cared for twenty-four neonates.[27][29] The entrance fee was 25 cents (equivalent to $8.48 in 2023)[1] while the adjoining shop and café offered souvenirs and refreshments. Proceeds totaling $181,632 (equivalent to $6.16 million in 2023)[1] helped fund Bayliss's project.[27] Inconsistent sanitation killed some babies, so glass walls were installed between them and visitors, shielding the infants.[30][failed verification] These developed into "isolettes" in modern neonatal intensive care units.

Electric streetcar – North American street railways from the early 19th century were being introduced to electric street railcars. An electric streetcar on a 1,400 feet (430 m) track demonstrated its speed, acceleration, and braking outside the Palace of Electricity.[17] Many downtown trams today are electric.