A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. Cattle drives ensure the herds' health in finding pasture and bring them to market. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the vaquero traditions of northern Mexico and became a figure of special significance and legend.[1] A subtype, called a wrangler, specifically tends the horses used to work cattle. In addition to ranch work, some cowboys work for or participate in rodeos. Cowgirls, first defined as such in the late 19th century, had a less well-documented historical role, but in the modern world work at identical tasks and have obtained considerable respect for their achievements.[2] Cattle handlers in many other parts of the world, particularly in South America and stockmen and jackaroos in Australia, perform work similar to the cowboy.

The cowboy has deep historic roots tracing back to Spain and the earliest European colonizers of the Americas. Over the centuries, differences in terrain and climate, and the influence of cattle-handling traditions from multiple cultures, created several distinct styles of equipment, clothing and animal handling. As the ever-practical cowboy adapted to the modern world, his equipment and techniques also adapted, though many classic traditions are preserved.

The English word cowboy has an origin from several earlier terms that referred to both age and to cattle or cattle-tending work. The English word cowboy was derived from vaquero, a Spanish word for an individual who managed cattle while mounted on horseback. Vaquero was derived from vaca, meaning "cow",[3] which came from the Latin word vacca. "Cowboy" was first used in print by Jonathan Swift in 1725, and was used in the British Isles from 1820 to 1850 to describe young boys who tended the family or community cows.[4][5] Originally though, the English word "cowherd" was used to describe a cattle herder (similar to "shepherd", a sheep herder), and often referred to a pre-adolescent or early adolescent boy, who usually worked on foot. This word is very old in the English language, originating prior to the year 1000.[6]

The term cowboy was in use by 1849,[7] although it was not used in all locations. The men who drove cattle for a living in the southwest were usually called cowhands, drovers, or stockmen.[8] Variations on the word appeared later. "Cowhand" appeared in about 1852, and "cowpoke" in 1881, originally restricted to the individuals who prodded cattle with long poles to load them onto railroad cars for shipping.[7] Names for a cowboy in American English include buckaroo, cowpoke, cowhand, and cowpuncher.[9] Another English word for a cowboy, buckaroo, is an anglicization of vaquero (Spanish pronunciation: [baˈkeɾo]).[10] Today, "cowboy" is a term common throughout the west and particularly in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, "buckaroo" is used primarily in the Great Basin and California, and "cowpuncher" mostly in Texas and surrounding states.[11]

Equestrianism required skills and an investment in horses and equipment rarely available to or entrusted to a child, though in some cultures boys rode a donkey while going to and from pasture. In antiquity, herding of sheep, cattle and goats was often the job of minors, and still is a task for young people in various Developing World cultures. Because of the time and physical ability needed to develop necessary skills, both historic and modern cowboys often began work as an adolescent. Historically, cowboys earned wages as soon as they developed sufficient skills to be hired (often as young as 12 or 13). If not disabled by injury, cowboys may handle cattle or horses for a lifetime. In the United States, a few women also took on the tasks of ranching and learned the necessary skills, though the "cowgirl" (discussed below) did not become widely recognized or acknowledged until the close of the 19th century.[12]

On western ranches today, the working cowboy is usually an adult. Responsibility for herding cattle or other livestock is no longer considered suitable for children or early adolescents. Boys and girls growing up in a ranch environment often learn to ride horses and perform basic ranch skills as soon as they are physically able, usually under adult supervision. Such youths, by their late teens, are often given responsibilities for "cowboy" work on the ranch.[12]

"Cowboy" was used during the American Revolution to describe American fighters who opposed the movement for independence. Claudius Smith, an outlaw identified with the Loyalist cause, was called the "Cow-boy of the Ramapos" due to his penchant for stealing oxen, cattle, and horses from colonists and giving them to the British.[13] In the same period, a number of guerrilla bands operated in Westchester County, which marked the dividing line between the British and American forces. These groups were made up of local farmhands who would ambush convoys and carry out raids on both sides. There were two separate groups: the "skinners" fought for the pro-independence side, while the "cowboys" supported the British.[14][15]

While cowhands were still respected in West Texas,[16] in the Tombstone, Arizona, area during the 1880s, the term "cowboy" or "cow-boy" was used pejoratively to describe men who had been implicated in various crimes.[17] One loosely organized band was dubbed "The Cowboys", and profited from smuggling cattle, alcohol, and tobacco across the U.S.–Mexico border.[18][19] Tombstone resident George Parsons wrote in his diary, "A cowboy is a rustler at times, and a rustler is a synonym for desperado—bandit, outlaw, and horse thief." The San Francisco Examiner wrote in an editorial, "Cowboys [are] the most reckless class of outlaws in that wild country ... infinitely worse than the ordinary robber."[17] It became an insult in the area to call someone a "cowboy", as it suggested he was a horse thief, robber, or outlaw. Cattlemen were generally called herders or ranchers.[18] Other synonyms for cowboy were ranch hand, range hand or trail hand, although duties and pay were not entirely identical.[20] The Cowboys' activities were ultimately curtailed by the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral and the resulting Earp Vendetta Ride.[17]

The origins of the cowboy tradition come from Spain, beginning with the hacienda system of medieval Spain. This style of cattle ranching spread throughout much of the Iberian Peninsula, and later was imported to the Americas. Both regions possessed a dry climate with sparse grass, thus large herds of cattle required vast amounts of land to obtain sufficient forage. The need to cover distances greater than a person on foot could manage gave rise to the development of the horseback-mounted vaquero.

.jpg/440px-Regimiento_de_Lanceros_de_Media_Luna_de_San_Miguel_el_Grande_(México,_siglo_XVIII).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Charro_Mexicano_(1828).jpg)

During the 16th century, the Conquistadors and other Spanish settlers brought their cattle-raising traditions as well as both horses and domesticated cattle to the Americas, starting with their arrival in what today is Mexico and Florida.[21] The traditions of Spain were transformed by the geographic, environmental and cultural circumstances of New Spain, which later became Mexico and the Southwestern United States. In turn, the land and people of the Americas also saw dramatic changes due to Spanish influence.

The arrival of horses was particularly significant, as equines had been extinct in the Americas since the end of the prehistoric ice age. Horses quickly multiplied in America and became crucial to the success of the Spanish and later settlers from other nations. The earliest horses were originally of Andalusian, Barb and Arabian ancestry,[22] but a number of uniquely American horse breeds developed in North and South America through selective breeding and by natural selection of animals that escaped to the wild. The mustang and other colonial horse breeds are now called "wild", but in reality are feral horses—descendants of domesticated animals.

Though popularly considered American, the traditional cowboy began with the Spanish tradition, which evolved further in what today is Mexico and the Southwestern United States into the vaquero of northern Mexico and the charro of the Jalisco and Michoacán regions. While most hacendados (ranch owners) were ethnically Spanish criollos,[23] many early vaqueros were Native Americans trained to work for the Spanish missions in caring for the mission herds.[24] Vaqueros went north with livestock. In 1598, Don Juan de Oñate sent an expedition across the Rio Grande into New Mexico, bringing along 7000 head of cattle. From this beginning, vaqueros drove cattle from New Mexico and later Texas to Mexico City.[25] Mexican traditions spread both South and North, influencing equestrian traditions from Argentina to Canada.[citation needed]

As English-speaking traders and settlers expanded westward, English and Spanish traditions, language and culture merged to some degree. Before the Mexican–American War in 1848, New England merchants who traveled by ship to California encountered both hacendados and vaqueros, trading manufactured goods for the hides and tallow produced from vast cattle ranches. American traders along what later became known as the Santa Fe Trail had similar contacts with vaquero life. Starting with these early encounters, the lifestyle and language of the vaquero began a transformation which merged with English cultural traditions and produced what became known in American culture as the "cowboy".[26]

.jpg/440px-Cazando_caballos_Mesteños_en_México_(1848).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Cattle_Branding_in_Mexico_(1870).jpg)

The arrival of English-speaking settlers in Texas began in 1821.[25] Rip Ford described the country between Laredo and Corpus Christi as inhabited by "countless droves of mustangs and ... wild cattle ... abandoned by Mexicans when they were ordered to evacuate the country between the Nueces and the Rio Grande by General Valentin Canalizo ... the horses and cattle abandoned invited the raids the Texians made upon this territory."[27] California, on the other hand, did not see a large influx of settlers from the United States until after the Mexican–American War. In slightly different ways, both areas contributed to the evolution of the iconic American cowboy. Particularly with the arrival of railroads and an increased demand for beef in the wake of the American Civil War, older traditions combined with the need to drive cattle from the ranches where they were raised to the nearest railheads, often hundreds of miles away.[1]

Black cowboys in the American West accounted for up to 25 percent of workers in the range-cattle industry from the 1860s to 1880s, estimated to be between 6,000 and 9,000 workers.[28][29] Typically former slaves or children of former slaves, many black men had skills in cattle handling and headed West at the end of the Civil War.[30]

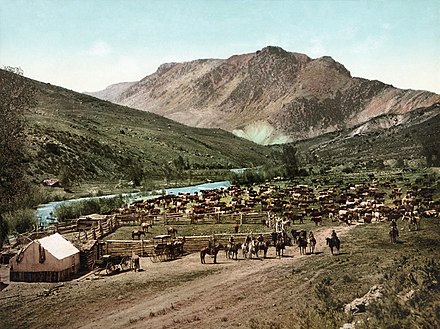

By the 1880s, the expansion of the cattle industry resulted in a need for additional open range. Thus many ranchers expanded into the northwest, where there were still large tracts of unsettled grassland. Texas cattle were herded north, into the Rocky Mountain west and the Dakotas.[31] The cowboy adapted much of his gear to the colder conditions, and westward movement of the industry also led to intermingling of regional traditions from California to Texas, often with the cowboy taking the most useful elements of each.

Mustang-runners or Mesteñeros were cowboys and vaqueros who caught, broke and drove mustangs to market in Mexico, and later American territories of what is now Northern Mexico, Texas, New Mexico and California. They caught the mustangs that roamed the Great Plains and the San Joaquin Valley of California, and later in the Great Basin, from the 18th century to the early 20th century.[32][33]

Large numbers of cattle lived in a semi-feral or a completely feral state on the open range and were left to graze, mostly untended, for much of the year. In many cases, different ranchers formed "associations" and grazed their cattle together on the same range. In order to determine the ownership of individual animals, they were marked with a distinctive brand, applied with a hot iron, usually while the cattle were still calves.[34]

In order to find young calves for branding, and to sort out mature animals intended for sale, ranchers would hold a roundup, usually in the spring.[35] A roundup required a number of specialized skills on the part of both cowboys and horses. Individuals who separated cattle from the herd required the highest level of skill and rode specially trained "cutting" horses, trained to follow the movements of cattle, capable of stopping and turning faster than other horses.[36] Once cattle were sorted, most cowboys were required to rope young calves and restrain them to be branded and (in the case of most bull calves) castrated. Occasionally it was also necessary to restrain older cattle for branding or other treatment.

A large number of horses were needed for a roundup. Each cowboy would require three to four fresh horses in the course of a day's work.[37] Horses themselves were also rounded up. It was common practice in the west for young foals to be born of tame mares, but allowed to grow up "wild" in a semi-feral state on the open range.[38] There were also "wild" herds, often known as mustangs. Both types were rounded up, and the mature animals tamed, a process called horse breaking, or "bronco-busting", usually performed by cowboys who specialized as horse trainers.[39] In some cases, extremely brutal methods were used to tame horses, and such animals tended to never be completely reliable. Other cowboys recognized their need to treat animals in a more humane fashion and modified their horse training methods,[40] often re-learning techniques used by the vaqueros, particularly those of the Californio tradition.[41] Horses trained in a gentler fashion were more reliable and useful for a wider variety of tasks.

Informal competition arose between cowboys seeking to test their cattle and horse-handling skills against one another, and thus, from the necessary tasks of the working cowboy, the sport of rodeo developed.[42]

Prior to the mid-19th century, most ranchers primarily raised cattle for their own needs and to sell surplus meat and hides locally. There was also a limited market for hides, horns, hooves, and tallow in assorted manufacturing processes.[43] While Texas contained vast herds of stray, free-ranging cattle available for free to anyone who could round them up,[25] prior to 1865, there was little demand for beef.[43] At the end of the American Civil War, Philip Danforth Armour opened a meat packing plant in Chicago, which became known as Armour and Company. With the expansion of the meat packing industry, the demand for beef increased significantly. By 1866, cattle could be sold to northern markets for as much as $40 per head, making it potentially profitable for cattle, particularly from Texas, to be herded long distances to market.[44]