Starved Rock State Park is a state park in the U.S. state of Illinois, characterized by the many canyons within its 2,630 acres (1,064 ha). Located just southeast of the village of Utica, in Deer Park Township, LaSalle County, Illinois, along the south bank of the Illinois River, the park hosts over two million visitors annually, the most for any Illinois state park.[1][2]

A flood from a melting glacier, known as the Kankakee Torrent, which took place approximately 14,000–19,000 years ago led to the topography of the site and its exposed rock canyons. Diverse forest plant life exists in the park and the area supports several wild animal species. Of particular interest has been sport fishing species.

Before European contact, the area was home to Native Americans, particularly the Kaskaskia who lived in the Grand Village of the Illinois across the river. Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette were the first Europeans recorded as exploring the region, and by 1683, the French had established Fort St. Louis on the large sandstone butte overlooking the river, they called Le Rocher (the Rock). Later after the French had moved on, according to a local legend, a group of Native Americans of the Illinois Confederation (also called Illiniwek or Illini) pursued by the Ottawa and Potawatomi fled to the butte in the late 18th century. In the legend, around 1769 the Ottawa and Potawatomi besieged the butte until all of the Illiniwek had starved, and the butte became known as "Starved Rock".

In the late 19th century, parkland around 'Starved Rock' was developed as a vacation resort. The resort was acquired by the State of Illinois in 1911 for a state park, which it remains today. Facilities in the park were built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, which have also gained historic designation. The Rock was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960. The park region has been the subject of several archeological studies concerning both native and European settlements, and various other archeological sites associated with the park were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

A catastrophic flood known as the Kankakee Torrent,[3] which took place somewhere between 14,000[4] and 17,000 years ago,[5] before humans occupied the area, helped create the park's signature geology and features, which are very unusual for the central plains.

The park is on the south bank of the Illinois River, a major tributary of the Mississippi River, between the Fox and Vermilion Rivers. The Vermilion created large sandbars at the junction of the Illinois, preventing practical navigation farther upriver. Rapids were found at the base of the butte before the construction of the Starved Rock Lock and Dam.[6]

Starved Rock is known for its outcrops of St. Peter Sandstone. The sandstone, typically buried, is exposed in this area due to an anticline, a convex fold in underlying strata. This creates canyons and cliffs when streams cut across the anticline. The sandstone is pure and poorly cemented, making it workable with a pick or shovel.[7] A similar geologic feature is found by near the Rock River between Dixon and Oregon, Illinois within Castle Rock State Park.[8]

Clovis points unearthed in the park indicate occupation by people of the Clovis Culture, which was widespread by about 11,000 BC. Clovis hunters specialized in hunting the large Pleistocene mammals, but a variety of other plants and animals were also exploited. Archeological surveys have located Archaic period (8000 – 2000 BC) settlements along the Illinois River. These prehistoric indigenous peoples thrived by foraging and hunting a variety of wild foods;[9] Havana Hopewell settlers during the Woodland period (1000 BC – 1000 AD) built earthwork mounds. They also made pottery and domesticated plants.

The growth of agriculture and maize surpluses supported the development of the complex Mississippian culture. Its peoples established permanent settlements in the Mississippi, Illinois, and Ohio river valleys. They harvested maize, beans, and pumpkins, and were noted for their copper ornaments. The first interaction with other tribes occurred during this period: artifacts from the major regional chiefdom and urban complex of Cahokia, at present-day Collinsville, Illinois, have been recovered at Illinois River sites.[9]

The earliest group of inhabitants recorded by the colonial French in the region were the historical Kaskaskia, whose large settlement on the north side of the Illinois River was known as the Grand Village of the Illinois. The Kaskaskia were members of the Illinois Confederation, who inhabited the region in the 16th through the 18th centuries. They lived in wigwams made of lightweight material. The natives could easily dismantle these structures when they traveled to hunt bison twice a year. The women gathered tubers from nearby swamps as a secondary source of food. Small bands of aggressive Iroquois settlers arrived in northern Illinois in 1660 in search of new hunting grounds for beaver, stimulating intertribal warfare. The Kaskaskia struggled with the Iroquois, who were armed with guns seized from or traded by Europeans in the eastern United States.[9]

In 1673 Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette were the first known Europeans to explore the northern portion of the Mississippi River. On their return, they navigated the Illinois River, which they found to be a convenient route to Lake Michigan. Along the river, they found seventy-three cabins in the Grand Village, whose population rapidly expanded in the next several years. Marquette returned to the village in 1675 to set up the Mission of the Immaculate Conception, the first Christian mission in modern-day Illinois. Marquette was joined by fellow Jesuit priest Claude-Jean Allouez in 1677. By 1680, the Grand Village was home to several hundred native cabins and a large population.[citation needed]

In 1680 the Iroquois temporarily drove the Kaskaskia out of the settlement during the Beaver Wars, as they were trying to expand their hunting territory. With an increase in French settlers in the area, the Kaskaskia returned by 1683. The French were able to provide the Kaskaskia with guns in exchange for other goods, which they used for defense against the powerful Iroquois, already armed by the English.[citation needed]

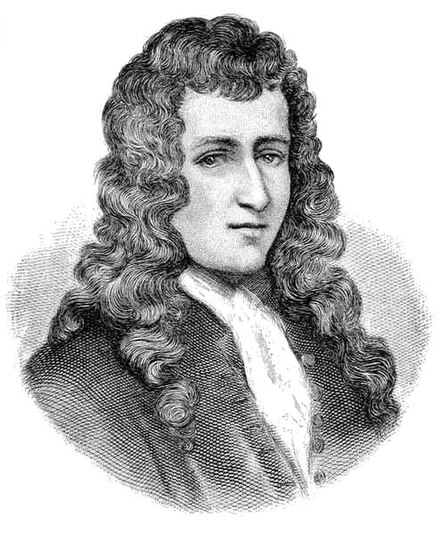

French explorers led by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and Henry de Tonty built Fort St. Louis on the large butte by the river in the winter of 1682.[10] Called Le Rocher, the butte provided an advantageous position for the fort above the Illinois River.[10] A wooden palisade was the only form of defense that La Salle used in securing the site. Inside the fort were a few wooden houses and native shelters. The French intended St. Louis to be the first of several forts to defend against English incursions and keep their settlements confined to the East Coast. Accompanying the French to the region were allied members of several native tribes from eastern areas, who integrated with the Kaskaskia: the Miami, Shawnee, and Mahican. The tribes established a new settlement at the base of the butte at a site now known as Hotel Plaza. After La Salle's five year monopoly ended, Governor Joseph-Antoine de La Barre wished to obtain Fort St. Louis along with Fort Frontenac for himself.[11] By orders of the governor, traders and his officers were escorted to Illinois.[11] On August 11, 1683, Prudhomme obtained approximately one and three quarters of a mile of the north portage shore.[11]

During the French and Indian Wars, the French used the fort as a refuge against attacks by the Iroquois, who were allied with the British. The Iroquois forced the settlers, then commanded by Henri de Tonty, to abandon the fort in 1691. De Tonty reorganized the settlers and constructed Fort Pimiteoui in modern-day Peoria.

French troops commanded by Pierre Deliette may have occupied Fort St. Louis from 1714 to 1718; Deliette's jurisdiction over the region ended when the territory was transferred from Canada to Louisiana. Fur trappers and traders used the fort periodically in the early 18th century until it became too dilapidated. No surface remains of the fort are found at the site today.

The region was periodically occupied by a variety of native tribes who were forced westward by the expansion of European settlements and the Beaver Wars. These included the Potawatomi and others.[12]

There are various local legends about how Starved Rock got its name. The most popular is a tale of revenge for the assassination of Ottawa leader Pontiac, who was killed in Cahokia on April 20, 1769, by an Illinois Confederation warrior. According to the legend, the Ottawa, along with their allies the Potawatomi, avenged Pontiac's death by attacking a band of Illiniwek along the Illinois River. The Illiniwek climbed to the butte to seek refuge, but their pursuers besieged the rock until the tribe starved to death, thereby giving the place the name "Starved Rock". The legend sometimes maintains, falsely, that this resulted in the complete extermination of the Illiniwek. Apart from oral history, there is no historical evidence that the siege happened. An early written report of the legend was related by Henry Schoolcraft in 1825.[13]

In 1919 Edgar Lee Masters, author of Spoon River Anthology, wrote a poem titled "Starved Rock" in which he voiced a dramatic elegy for the Illini tribe whose tragic death thus gave rise to the name of the dramatic butte overlooking the Illinois River. (Macmillan Company, N.Y., 1919.)

Daniel Hitt purchased the land that is today occupied by Starved Rock State Park from the United States Government in 1835 for $85 as compensation for his tenure in the U.S. Army. He sold the land in 1890 to Ferdinand Walther for $15,000.[citation needed] Recognizing the potential for developing the land as a resort, Walther constructed the Starved Rock Hotel and a natural pool near the base of Starved Rock, as well as a concession stand and dance hall. The French and Native American heritage of the region also drew visitors to the site. Walthers set up a variety of walkable trails and harbored small boats near the hotel that made trips along the Illinois River. Visitors could also visit Deer Park (modern-day Matthiessen State Park) a few miles to the south.[citation needed]

With the growth of competitive sites, Walther struggled to keep the complex economically stable. In 1911,[14] he sold the land to the Illinois State Parks Commission for $146,000.[15][16][17] The Commission was initially headquartered at Starved Rock State Park after the land was acquired.[18] The state initially acquired 898 acres and opened Starved Rock State Park as a public facility in 1912.[17]

During its early years, Starved Rock State Park was directly accessible only by railroad.[19] Visitors had reached Starved Rock by rail and ferry since at least 1904, while the property was still a Walther-run resort.[20] Between 1904 and 1908 more than 160,000 people used the ferry that connected Starved Rock to the electric railway line.[20] In 1912, the year the park was opened to the public, attendance was 75,000.[20] By the 1930s other state parks were opened in Illinois but Starved Rock State Park remained the most extensively used park in the system.[21]

Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal legislation in the 1930s called for the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to provide jobs for young men.[22] The focus of this group was to preserve natural areas in the rural United States. CCC Camp 614 was deployed to Starved Rock State Park from the Jefferson Barracks Military Post in Missouri.[22] Unlike most CCC groups in the nation, Camp 614 included African Americans.[22] The group, composed of roughly 200 men,[22] constructed trails, shelters, and benches throughout the park. In 1933, the group was joined by Camp 1609 from Fort Sheridan via Readstown, Wisconsin. Camp 1609 constructed the Starved Rock Lodge, several surrounding log cabins, and a large parking lot. The lodge was particularly noted for its elegant fireplaces