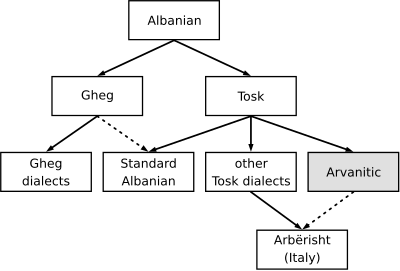

Arbëresh (gluha/gjuha/gjufa Arbëreshe; also known as Arbërisht) is the variety of Albanian spoken by the Arbëreshë people of Italy. It is derived from the Albanian Tosk spoken in Albania in the southwestern Balkans. Another similar Tosk Albanian variety is spoken in Greece by the Arvanites: Arvanitika.

Between the 11th and 14th centuries, Albanian-speaking mercenaries from the areas of medieval Albania, Epirus and Morea now Peloponesse, were often recruited by the Franks, Aragonese, Italians and Byzantines.

The invasion of the Balkans by the Ottoman Turks in the 15th century caused large waves of emigration from the Balkans to southern Italy. In 1448, the King of Naples, Alfonso V of Aragon, asked the Albanian noble Skanderbeg to transfer to his service ethnic Albanian mercenaries. Led by Demetrio Reres and his two sons, these men and their families were settled in twelve villages in the Catanzaro area of Calabria. The following year, some of their relatives and other Albanians were settled in four villages in Sicily.[2][3] In 1459 Ferdinand I of Naples also requested assistance from Skanderbeg. After victories in two battles, a second contingent of Albanians was rewarded with land east of Taranto, in Apulia, where they founded 15 villages.[4][5] After the death of Skanderbeg (1468), resistance to the Ottomans in Albania came to an end. Subsequently, many Albanians fled to neighbouring countries and some settled in villages in Calabria.

There was a constant flow of ethnic Albanians into Italy into the 16th century, and other Albanian villages were formed on Italian soil.[6][5] The new immigrants often took up work as mercenaries with Italian armies. For instance, between 1500 and 1534, Albanians from central Greece were employed as mercenaries by Venice, to evacuate its colonies in the Peloponnese, as the Turks invaded. Afterwards these troops reinforced defences in southern Italy against the threat of Turkish invasion. They established self-contained communities, which enabled their distinct language and culture to flourish. Arbëreshë, as they became known, were often soldiers for the Kingdom of Naples and the Republic of Venice, between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Despite an Arbëreshë cultural and artistic revival in the 19th century, emigration from southern Italy significantly reduced the population. In particular, migration to the Americas between 1900 and 1940 caused the total depopulation of approximately half of the Arbëreshë villages. The speech community forms part of the highly heterogenous linguistic landscape of Italy, with 12 recognised linguistic minorities Italian state law (law 482/1999).[7] The exact Arbëresh speech population is uncertain, as the Italian national census does not collect data on minority language speakers. This is also further complicated by the Italian state's protection of the Albanian culture and population as a whole and not Arbëresh Albanian specifically. This law theoretically implements specific measures in various fields such as education, communication, radio, press and TV public service, but in the case of the Arberesh community the legal construction of the language as "Albanian" and the community as the "Albanian population" effectively homogenises the language and has not led to adequate provision for the linguistic needs of the communities.[citation needed]

Arbëresh derives from a medieval variety of Tosk, which was spoken in southern Albania and from which the modern Tosk is also derived. It follows a similar evolutionary pattern to Arvanitika, a similar language spoken in Greece. Arbëresh is spoken in Southern Italy in the regions of Abruzzi, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Molise, Apulia and Sicily. The varieties of Arbëresh are closely related to each other but are not always entirely mutually intelligible.

Arbëresh retains many features of medieval Albanian from the time before the Ottoman invasion of Albania in the 15th century. It also retains some Greek elements, including vocabulary and pronunciation, most of which it shares with its relative Arvanitika. Many of the conservative features of Arbëresh were lost in mainstream Albanian Tosk. For example, it has preserved certain syllable-initial consonant clusters which have been simplified in Standard Albanian (cf. Arbëresh gluhë /ˈɡluxə/ ('language/tongue'), vs. Standard Albanian gjuhë /ˈɟuhə/). Arbëresh most resembles the dialect of Albanian spoken in the southern region of Albania, and also that of Çam Albanians.

Arbëresh was commonly called Albanese ('Albanian' in the Italian language) in Italy until the 1990s. Until the 1980s Arbëresh was mostly a spoken language, except for its written form used in the Italo-Albanian Byzantine Church, and Arbëreshë people had no practical connection with the Standard Albanian language used in Albania, as they did not use the standard Albanian form of writing.[8]

Since the 1980s, some efforts have been organized to preserve the cultural and linguistic heritage of the language.[citation needed]

Arbëresh has been replaced by local Romance languages and by Italian in several villages, and in others is experiencing contact-induced language shift. Many scholars have produced language learning materials for communities, including those by Giuseppe Schirò Di Maggio, Gaetano Gerbino, Matteo Mandalà, Zef Chiaramonte.

Arbëresh language beside medieval mainland Tosk Albanian is also descended from Arvanitika which evolved separately from other forms of Albanian since the 13th century when its first speakers emigrated to Morea from Southern Albania and Epirus.[9] A dialect is defined linguistically as closely related and, despite their differences, by mutual intelligibility.[citation needed] In the absence of rigorous linguistic intelligibility tests, the claim cannot be made whether one is a dialect or a separate variant of the same language group.[10][8][11][12]

The varieties of Arbëresh largely correspond with the regions where they are spoken, while some settlements have distinctive features that result in greater or lesser degrees of mutual intelligibility.

The Siculo-Arbëresh variety is spoken exclusively in the Province of Palermo and in three villages: Piana degli Albanesi, Santa Cristina Gela and Contessa Entellina; while the varieties of Piana and Santa Cristina Gela are similar enough to be entirely mutually intelligible, the variety of Contessa Entellina is not entirely intelligible. Therefore a further dialect within Siculo-Arbëresh known as the Palermitan-Arbëresh variety can be identified,[13] as well as a Cosenza variety, a Basilicata variety, and a Campania variety represented by the speech of one single settlement of Greci. There is also a Molisan-Arbëresh and an Apulio-Arbëresh.

Within the Cosenza Calabrian varieties of Arbëresh, the dialect of Vaccarizzo Albanese is particularly distinct. Spoken in the villages of Vaccarizzo Albanese and San Giorgio Albanese in Calabria by approximately 3,000 people, Vaccarizzo Albanian has retained many archaic features of both Gheg and Tosk dialects.

Some features of Arbëresh distinguish it considerably from standard Albanian while also maintaining features still used in other Tosk Albanian dialects. In some cases these are retentions of older pronunciations.

The letter ⟨Ë⟩ is pronounced as either a mid central vowel [ə] or as a close back unrounded vowel [ɯ]. So the word Arbëresh is pronounced either [ɑɾbəˈɾɛʃ] or [ɑɾbɯˈɾɛʃ] depending on the dialect.

Arbëresh lacks the close front rounded vowel [y] of Albanian, which is replaced by the close front unrounded vowel [i]. For example ty ('you') becomes tihj, and hyni ('enter') becomes hini.

GJ, Q

The letters ⟨GJ⟩ and ⟨Q⟩ are pronounced as a palatalized voiced velar plosive [ɡʲ] and a palatalized voiceless velar plosive [kʲ], rather than a voiced palatal plosive [ɟ] and a voiceless palatal plosive [c] as in standard Albanian. E.g. the word gjith ('all') is pronounced [ɡʲiθ] rather than [ɟiθ], qiell ('heaven') is pronounced [kʲiɛx] rather than [ciɛɫ], and shqip ('Albanian') is pronounced [ʃkʲɪp].

GL, KL

In some words, Arbëresh has preserved the consonant clusters /ɡl/ and /kl/. In Standard Albanian these have mostly become the palatal stops gj and q, e.g. glet not gjet ('s/he looks like ... '), klumësht not qumësht ('milk'), and klisha instead of kisha ('church').

H, HJ

The letter ⟨H⟩ is pronounced as a voiceless velar fricative [x]. As such, the Albanian word ha ('eat') is pronounced [xɑ], not [hɑ]. Arbëresh additionally has the palatalized counterpart, [ç]. Therefore, the word hjedh ('throw') is pronounced [çɛθ]. The letter combination ⟨HJ⟩ is present in a few standard Albanian words (without a voiceless velar fricative), but is not treated as a separate letter of the alphabet as it is in Arbëresh.

LL, G, GH

The letters ⟨LL⟩ and ⟨G⟩ are realised as a voiced velar fricative [ɣ]. The vast majority of these words originate in Sicilian, but the sound also occurs in words of Albanian origin. Often ⟨G⟩ when pronounced [ɣ] is replaced by ⟨GH⟩ in the Arbëresh orthography, with ⟨G⟩ in theory reserved for /g/ (although in practice it is inconsistent). This feature is very strong that it is carried over into the Italian speech of inhabitants of Piana degli Albanesi and Santa Cristina Gela in words such as grazie, frigorifero, gallera, magro, gamba etc. which are realised respectively as [ʁratsiɛ], [friɣoˈrifero], [ɣaˈlɛra], [ˈmaɣro], [ˈʁamba] etc.[14][15] In Piana degli Albanesi the tendency is to treat Italian loanwords differently from Sicilian, which results in the difference between llampjun, pronounced as [ʁampˈjun] (from lampione, 'lamp post'), and lampadhin, pronounced as [lampaˈðin] (from Italian lampadina). In the first example, the ⟨L⟩ becomes ⟨LL⟩ [ʁ] because it comes from Sicilian,[why?] whereas in the process of transference from the Italian lampadina to Arbëresh lampadhin, the ⟨l⟩ does not change but the ⟨d⟩ becomes [ð].

Arbëresh has retained an archaic system[citation needed] of final devoicing of consonants in contrast with Standard Albanian. The consonants that change when in final position or before another consonant are the voiced stops b, d, g, gj; the voiced affricates x, xh; and the voiced fricatives dh, ll, v, z, zh.

Examples:

Stress in Arbëresh is usually on the penultimate syllable, as in Italian.

In Arbëresh, just like in Tosk, the first person present indicative (e.g. "I work") is marked by the word ending in NJ, whereas in standard Albanian this is normally marked by J.

So, 'I live' is rrónj in Arbëresh and rroj in standard Albanian. The present continuous or gerund differs from Standard Albanian; Arbëresh uses the form "jam'e bënj" instead of "po bej" (I am doing).

The adoption of words of ancient Greek origin or of the Koine comes above all from their use in Byzantine religious practices, when the corresponding use in Albanian declined, the "courtly" one of the church was used. The Arberesh use ancient Greek in their liturgies. Thus synonyms are created, such as parkales or lutje for the word "prayer".

Some Arbëresh words appear to be of Koine Greek influence. Examples:

Some Arbëresh words appear to be of Albanian Arvanitika which has influenced the current Greek areas since the Middle Ages. Examples:

On the Koine Greek elements in the Italo-Albanian dialects see T. Jochalas (1975).[16]

In the Arbëresh varieties of Sicily and Calabria there are loanwords from the Sicilian language that have crystallized into the Arberesh language matrix at some time in the past but have now mostly disappeared, or evolved in the Romance vocabulary of the local population. This also occurs in other Arberesh varieties outside of Sicily with the local Romance varieties of their communities.

Examples:

Alongside the Sicilian vocabulary element in Siculo-Arbëresh, the language also includes grammatical rules for the incorporation of Sicilian-derived verbs in Arbëresh, which differs from the rules concerning Albanian lexical material.

Examples:

In the past tense this conjugates as follows:

The Arbëresh diminutive and augmentative system is calqued from Sicilian and takes the form of /-ats(-ɛ)/ = Sic. -azz(u/a); for example "kalac" (cavallone/big horse), and the diminutive takes the form of /-tʃ-ɛl(-ɛ) from Sic. /-c-edd(u/a); for example "vajziçele" (raggazzina/little girl).The Arbëresh word for "swear word" is "fjalac" and comes from a fusion of the Arbëresh word of Albanian etymology: "fjalë" plus the Sicilian augmentative /-azz[a]/ minus the feminine gendered ending /-a/; this calques the Sicilian word 'palurazza' which is cognate with Italian 'parolaccia'.[15]

There are many instances in which Arberisht differs greatly from Standard Albanian, for instance:

There are many elements of Arberesh grammar that differ considerably from Albanian, for example:

The name Arbërishte is derived from the ethnonym "Albanoi", which in turn comes from the toponym "Arbëria" (Greek: Άρβανα), which in the Middle Ages referred to a region in what is today Albania (Babiniotis 1998). Its native equivalents (Arbërorë, Arbëreshë and others) used to be the self-designation of Albanians in general. Both "Arbëria" and "Albania/Albanian" go further back to name forms attested since antiquity.

Within the Arbëresh community the language is often referred to as "Tarbrisht" or "Gjegje". The origin of the term "gjegje" is uncertain, however this does mean "listen" in Arbërisht. Gheg is also the name of one of the two major dialects of Albanian as spoken in the Balkans. According to the writer Arshi Pipa, the term Gegë was initially used for confessional denotation, being used in pre-Ottoman Albania by its Orthodox population when referring to their Catholic neighbors.

[17]

Every Italo-Albanian person is given a legal Italian name and also a name in Albanian Arbërisht. Quite often the Arbëresh name is merely a translation of the Italian name. Arbëresh surnames are also used amongst villagers but do not carry any legal weight; the Arbëresh surname is called an "ofiqe" in Arbërisht. Some Arbëresh 'ofiqe' are 'Butijuni', 'Pafundi', 'Skarpari' (shoemaker from Italian word 'scarpa').

Examples of Italian names and their Arbëresh equivalents:

The language is not usually written outside of the church and a few highly educated families, but officials are now using the standard Albanian alphabet, which is used on street signs in villages as well as being taught in schools.

Demonstrative pronouns replace nouns once they are able to be understood from their context.

...was a confessional name in pre-Ottoman Albania.