The Hanseatic League[a] was a medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German towns in the late 12th century, the League expanded between the 13th and 15th centuries and ultimately encompassed nearly 200 settlements across eight modern-day countries, ranging from Estonia in the north and east, to the Netherlands in the west, and extended inland as far as Cologne, the Prussian regions and Kraków, Poland.

The League began as a collection of loosely associated groups of German traders and towns aiming to expand their commercial interests, including protection against robbery. Over time, these arrangements evolved into the League, offering traders toll privileges and protection on affiliated territory and trade routes. Economic interdependence and familial connections among merchant families led to deeper political integration and the reduction of trade barriers. This gradual process involved standardizing trade regulations among Hanseatic Cities.

During its time, the Hanseatic League dominated maritime trade in the North and Baltic Seas. It established a network of trading posts in numerous towns and cities, notably the Kontors in London (known as the Steelyard), Bruges, Bergen, and Novgorod, which became extraterritorial entities that enjoyed considerable legal autonomy. Hanseatic merchants, commonly referred to as Hansards, operated private companies and were known for their access to commodities, and enjoyed privileges and protections abroad. The League's economic power enabled it to impose blockades and even wage war against kingdoms and principalities.

Even at its peak, the Hanseatic League remained a loosely aligned confederation of city-states. It lacked a permanent administrative body, a treasury, and a standing military force. In the 14th century, the Hanseatic League instated an irregular negotiating diet that operated based on deliberation and consensus. By the mid-16th century, these weak connections left the Hanseatic League vulnerable, and it gradually unraveled as members merged into other realms or departed, ultimately disintegrating in 1669.

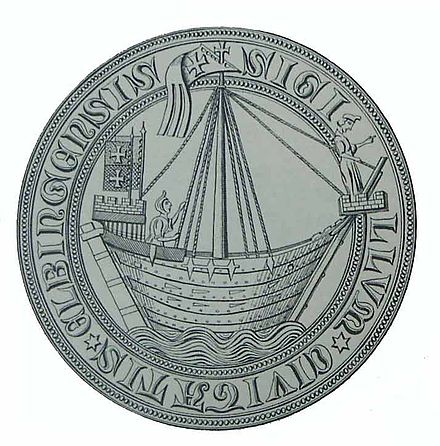

The League used a variety of vessel types for shipping across the seas and navigating rivers. The most emblematic type was the cog. Expressing diversity in construction, it was depicted on Hanseatic seals and coats of arms. By the end of the Middle Ages, the cog was replaced by types like the hulk, which later gave way to larger carvel ships.

Hanse is the Old High German word for a band or troop.[4] This word was applied to bands of merchants traveling between the Hanseatic cities.[5] Hanse in Middle Low German came to mean a society of merchants or a trader guild.[6] Claims that it originally meant An-See, or "on the sea", are incorrect.[7]: 145

Exploratory trading ventures, raids, and piracy occurred throughout the Baltic Sea. The sailors of Gotland sailed up rivers as far away as Novgorod,[8] which was a major Rus trade centre. Scandinavians led the Baltic trade before the League, establishing major trading hubs at Birka, Haithabu, and Schleswig by the 9th century CE. The later Hanseatic ports between Mecklenburg and Königsberg (present-day Kaliningrad) originally formed part of the Scandinavian-led Baltic trade system.[9]

The Hanseatic League was never formally founded, so it lacks a date of foundation.[10]: 2 Historians traditionally traced its origins to the rebuilding of the north German town of Lübeck in 1159 by the powerful Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, after he had captured the area from Adolf II, Count of Schauenburg and Holstein. More recent scholarship has deemphasized Lübeck, viewing it as one of several regional trading centers,[11] and presenting the League as the combination of a north German trading system oriented on the Baltic and a Rhinelandic trading system targeting England and Flanders.[12]

German cities speedily dominated trade in the Baltic during the 13th century, and Lübeck became a central node in the seaborne trade that linked the areas around the North and Baltic seas. Lübeck hegemony peaked during the 15th century.[13]

Well before the term Hanse appeared in a document in 1267,[14] in different cities began to form guilds, or hansas, with the intention of trading with overseas towns, especially in the economically less-developed eastern Baltic. This area could supply timber, wax, amber, resins, and furs, along with rye and wheat brought on barges from the hinterland to port markets. Merchant guilds formed in hometowns and destination ports as medieval corporations (universitates mercatorum),[15]: 42–43 and despite competition increasingly cooperated to coalesce into the Hanseatic network of merchant guilds. The dominant language of trade was Middle Low German, which had a significant impact on the languages spoken in the area, particularly the larger Scandinavian languages,[16]: 1222–1233 [17]: 1933–1934 Estonian,[18]: 288 and Latvian.[19]: 230–231

Visby, on the island of Gotland, functioned as the leading center in the Baltic before the Hansa. Sailing east, Visby merchants established a trading post at Novgorod called Gutagard (also known as Gotenhof) in 1080.[20] In 1120, Gotland gained autonomy from Sweden and admitted traders from its southern and western regions.[15]: 26 Thereafter, under a treaty with the Visby Hansa, northern German merchants made regular stops at Gotland.[21] In the first half of the 13th century, they established their own trading station or Kontor in Novgorod, known as the Peterhof, up the river Volkhov.[22]

Lübeck soon became a base for merchants from Saxony and Westphalia trading eastward and northward; for them, because of its shorter and easier access route and better legal protections, it was more attractive than Schleswig.[15]: 27 It became a transshipment port for trade between the North Sea and the Baltics. Lübeck also granted extensive trade privileges to Russian and Scandinavian traders.[15]: 27–28 It was the main supply port for the Northern Crusades, improving its standing with various Popes. Lübeck gained imperial privileges to become a free imperial city in 1226, under Valdemar II of Denmark during the Danish dominion, as had Hamburg in 1189. Also in this period Wismar, Rostock, Stralsund, and Danzig received city charters.[15]: 50–52

Hansa societies worked to remove trade restrictions for their members. The earliest documentary mention (although without a name) of a specific German commercial federation dates between 1173 and 1175 (commonly misdated to 1157) in London. That year, the merchants of the Hansa in Cologne convinced King Henry II of England to exempt them from all tolls in London[23] and to grant protection to merchants and goods throughout England.[24]: 14–17

German colonists in the 12th and 13th centuries settled in numerous cities on and near the east Baltic coast, such as Elbing (Elbląg), Thorn (Toruń), Reval (Tallinn), Riga, and Dorpat (Tartu), all of which joined the League, and some of which retain Hansa buildings and bear the style of their Hanseatic days. Most adopted Lübeck law, after the league's most prominent town.[25] The law provided that they appeal in all legal matters to Lübeck's city council. Others, like Danzig from 1295 onwards, had Magdeburg law or its derivative, Culm law.[26][27][28] Later, the Livonian Confederation of 1435 to c. 1582 incorporated modern-day Estonia and parts of Latvia; all of its major towns were members of the League.

Over the 13th century, older and wealthier long-distance traders increasingly chose to settle in their hometowns as trade leaders, transitioning from their previous roles as landowners. The growing number of settled merchants afforded long-distance traders greater influence over town policies. Coupled with an increased presence in the ministerial class, this elevated the status of merchants and enabled them to expand to and assert dominance over more cities.[15]: 44, 47–50 [29]: 27–28 This decentralized arrangement was fostered by slow travel speeds: moving from Reval to Lübeck took between 4 weeks and, in winter, 4 months.[30]: 202

In 1241, Lübeck, which had access to the Baltic and North seas' fishing grounds, formed an alliance—a precursor to the League—with the trade city of Hamburg, which controlled access to the salt-trade routes from Lüneburg. These cities gained control over most of the salt-fish trade, especially the Scania Market; Cologne joined them in the Diet of 1260. The towns raised their armies, with each guild required to provide levies when needed. The Hanseatic cities aided one another, and commercial ships often served to carry soldiers and their arms. The network of alliances grew to include a flexible roster of 70 to 170 cities.[31]

In the West, cities of the Rhineland such as Cologne enjoyed trading privileges in Flanders and England.[12] In 1266, King Henry III of England granted the Lübeck and Hamburg Hansa a charter for operations in England, initially causing competition with the Westphalians. But the Cologne Hansa and the Wendish Hansa joined in 1282 to form the Hanseatic colony in London, although they didn't completely merge until the 15th century. Novgorod was blockaded in 1268 and 1277/1278.[15]: 58–59 Nonetheless, Westphalian traders continued to dominate trade in London and also Ipswich and Colchester, while Baltic and Wendish traders concentrated between King's Lynn and Newcastle upon Tyne.[15]: 36 Much of the drive for cooperation came from the fragmented nature of existing territorial governments, which did not provide security for trade. Over the next 50 years, the merchant Hansa solidified with formal agreements for co-operation covering the west and east trade routes.[citation needed] Cities from the east modern-day Low Countries, but also Utrecht, Holland, Zealand, Brabant, Namur, and modern Limburg joined in participation over the thirteenth century.[32]: 111 This network of Hanseatic trading guilds became called the Kaufmannshanse in historiography.

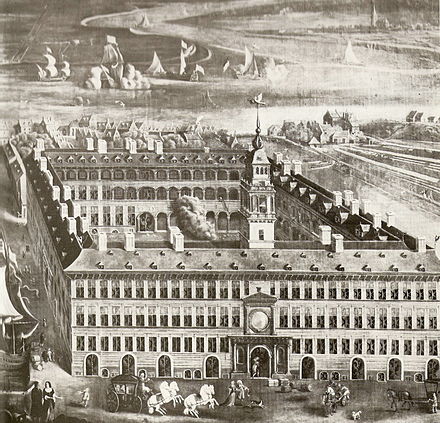

The League succeeded in establishing additional Kontors in Bruges (Flanders), Bryggen in Bergen (Norway), and London (England) beside the Peterhof in Novgorod. These trading posts were institutionalised by the first half of the 14th century (for Bergen and Bruges)[15]: 62 [33]: 65 and, except for the Kontor of Bruges, became significant enclaves. The London Kontor, the Steelyard, stood west of London Bridge near Upper Thames Street, on the site later occupied by Cannon Street station. It grew into a walled community with its warehouses, weigh house, church, offices, and homes.

In addition to the major Kontors, individual ports with Hanseatic trading outposts or factories had a representative merchant and warehouse. Often they were not permanently manned. In Scania, Denmark, around 30 Hanseatic seasonal factories produced salted herring, these were called vitten and were granted legal autonomy to the extent that Burkhardt argues that they resembled a fifth kontor and would be seen as such if not for their early decline.[34]: 157–158 In England, factories in Boston (the outpost was also called Stalhof), Bristol, Bishop's Lynn (later King's Lynn, which featured the sole remaining Hanseatic warehouse in England), Hull, Ipswich, Newcastle upon Tyne, Norwich, Scarborough, Yarmouth (now Great Yarmouth), and York, many of which were important for the Baltic trade and became centers of the textile industry in the late 14th century. Hansards and textile manufacturers coordinated to make fabrics meet local demand and fashion in the traders' hometowns. Outposts in Lisbon, Bordeaux, Bourgneuf, La Rochelle and Nantes offered the cheaper Bay salt. Ships that plied this trade sailed in the salt fleet. Trading posts operated in Flanders, Denmark-Norway, the Baltic interior, Upper Germany, Iceland, and Venice.[34]: 158–160

Hanseatic trade was not exclusively maritime, or even over water. Most Hanseatic towns did not have immediate access to the sea and many were linked to partners by river trade or even land trade. These formed an integrated network, while many smaller Hanseatic towns had their main trading activity in subregional trade. Internal Hanseatic trade was the Hanse's quantitatively largest and most important business.[34]: 153, 161 Trade over rivers and land was not tied to specific Hanseatic privileges, but seaports such as Bremen, Hamburg and Riga dominated trade on their rivers. This was not possible for the Rhine where trade retained an open character. Digging canals for trade was uncommon, although the Stecknitz Canal was built between Lübeck and Lauenburg from 1391 to 1398.[35]: 145–147, 158–159

Starting with trade in coarse woolen fabrics, the Hanseatic League increased both commerce and industry in northern Germany. As trade increased, finer woolen and linen fabrics, and even silks, were manufactured in northern Germany. The same refinement of products out of the cottage industry occurred in other fields, e.g. etching, wood carving, armor production, engraving of metals, and wood-turning.

The league primarily traded beeswax, furs, timber, resin (or tar), flax, honey, wheat, and rye from the east to Flanders and England with cloth, in particular broadcloth, (and, increasingly, manufactured goods) going in the other direction. Metal ore (principally copper and iron) and herring came south from Sweden, while the Carpathians were another important source of copper and iron, often sold in Thorn. Lubeck had a vital role in the salt trade; salt was acquired in Lüneburg or shipped from France and Portugal and sold on Central European markets, taken to Scania to salt herring, or exported to Russia. Stockfish was traded from Bergen in exchange for grain; Hanseatic grain inflows allowed more permanent settlements further north in Norway. The league also traded beer, with beer from Hanseatic towns the most valued, and Wendish cities like Lübeck, Hamburg, Wismar, and Rostock developed export breweries for hopped beer.[36]: 45–61 [37]: 35–36 [38]: 72 [39]: 141 [30]: 207–233

The Hanseatic League, at first the merchant hansas and eventually its cities, relied on power to secure protection and gain and preserve privileges. Bandits and pirates were persistent problems; during wars, these could be joined by privateers. Traders could be arrested abroad and their goods could be confiscated.[12] The league sought to codify protection; internal treaties established mutual defense and external treaties codified privileges.[15]: 53

Many locals, merchant and noble alike, envied the League's power and tried to diminish it. For example, in London, local merchants exerted continuing pressure for the revocation of privileges.[33]: 96–98 Most foreign cities confined Hanseatic traders to specific trading areas and their trading posts.[34]: 128, 143 The refusal of the Hansa to offer reciprocal arrangements to their counterparts exacerbated the tension.[40]: 105–111

League merchants used their economic power to pressure cities and rulers. They called embargoes, redirected trade away from towns, and boycotted entire countries. Blockades were erected against Novgorod in 1268 and 1277/1278.[15]: 58 Bruges was pressured by temporarily moving the Hanseatic emporium to Aardenburg from 1280 to 1282,[15]: 58 [41]: 19–21 from 1307 or 1308 to 1310 [41]: 20–21 and in 1350,[29]: 29 to Dordt in 1358 and 1388, and to Antwerp in 1436.[33]: 68, 80, 92 Boycotts against Norway in 1284[29]: 28 and Flanders in 1358 nearly caused famines.[33]: 68 They sometimes resorted to military action. Several Hanseatic cities maintained their warships and in times of need, repurposed merchant ships. Military action against political powers often involved an ad hoc coalition of stakeholders, called an alliance (tohopesate).[29]: 32, 39–40 [33]: 93–95

As an essential part of protecting their investments, League members trained pilots and erected lighthouses,[42] including Kõpu Lighthouse.[43][12] Lübeck erected in 1202 what may be northern Europe's first proper lighthouse in Falsterbo. By 1600 at least 15 lighthouses had been erected along the German and Scandinavian coasts, making it the best-lighted coast in the world, largely thanks to the Hansa.[44]

.jpg/440px-Stargard_Szczec_Brama_Mlynska_(1).jpg)

The weakening of imperial power and imperial protection under the late Hohenstaufen dynasty forced the League to institutionalize a cooperating network of cities with a fluid structure, called the Städtehanse,[29]: 27 but it never became a formal organization and the Kaufmannshanse continued to exist.[29]: 28–29 This development was delayed by the conquest of Wendish cities by the Danish king Eric VI Menved or by their feudal overlords between 1306 and 1319 and the restriction of their autonomy.[15]: 60–61 Assemblies of the Hanse towns met irregularly in Lübeck for a Hansetag (Hanseatic Diet) – starting either around 1300,[15]: 59 or possibly 1356.[33]: 66 Many towns chose not to attend nor to send representatives, and decisions were not binding on individual cities if their delegates were not included in the recesses; representatives would sometimes leave the Diet prematurely to give their towns an excuse not to ratify decisions.[29]: 36–39 [b] Only a few Hanseatic cities were free imperial cities or enjoyed comparable autonomy and liberties, but many temporarily escaped domination by local nobility.[45]

Between 1361 and 1370, League members fought against Denmark in the Danish-Hanseatic War. Though initially unsuccessful with a Wendish offensive, towns from Prussia and the Netherlands, and eventually joined by Wendish towns, allied in the Confederation of Cologne in 1368, sacked Copenhagen and Helsingborg, and forced Valdemar IV, King of Denmark, and his son-in-law Haakon VI, King of Norway, to grant tax exemptions and influence over Øresund fortresses for 15 years in the peace treaty of Stralsund in 1370. It extended privileges in Scania to the League, including Holland and Zeeland. The treaty marked the height of Hanseatic influence; for this period the League was called a "Northern European great power". The Confederation lasted until 1385, while the Øresund fortresses were returned to Denmark that year.[33]: 64, 70–73

After Valdemar's heir Olav died, a succession dispute erupted over Denmark and Norway between Albert of Mecklenburg, King of Sweden and Margaret I, Queen of Denmark. This was further complicated when Swedish nobles rebelled against Albert and invited Margaret. Albert was taken prisoner in 1389, but hired privateers in 1392, the socalled Victual Brothers, who took Bornholm and Visby in his name. They and their descendants threatened maritime trade between 1392 and the 1430s. Under the 1395 release agreement for Albert, Stockholm was ruled from 1395 to 1398 by a consortium of 7 Hanseatic cities, and enjoyed full Hanseatic trading privileges. It went to Margaret in 1398.[33]: 76–77

The Victual Brothers controlled Gotland in 1398. It was conquered by the Teutonic Order with support from the Prussian towns and its privileges were restored. The grandmaster of the Teutonic Order was often seen as the head of the Hanse (caput Hansae), both abroad and by some League members.[33]: 77–78 [29]: 31–32

Over the 15th century, the League became further institutionalized. This was in part a response to challenges in governance and competition with rivals, but also reflected changes in trade. A slow shift occurred from loose participation to formal recognition/revocation.[32]: 113–115 Another general trend was Hanseatic cities' increased legislation of their kontors abroad. Only the Bergen kontor grew more independent in this period.[34]: 136

In Novgorod, after extended conflict since the 1380s, the League regained its trade privileges in 1392, agreeing to Russian trade privileges for Livonia and Gotland.[33]: 78–83

In 1424, all German traders of the Petershof kontor in Novgorod were imprisoned and 36 of them died. Although rare, arrests and seizures in Novgorod were particularly violent.[46]: 182 In response, and due to the ongoing war between Novgorod and the Livonian Order, the League blockaded Novgorod and abandoned the Peterhof from 1443 to 1448.[47]: 82

After extended conflicts with the League from the 1370s, English traders gained trade privileges in the Prussian region via the treaties of Marienburg (the first in 1388, the last in 1409).[33]: 78–83 Their influence increased, while the importance of Hanseatic trade in England decreased over the 15th century.[33]: 98

Over the 15th century, tensions between the Prussian region and the "Wendish" cities (Lübeck and its eastern neighbours) increased. Lübeck was dependent on its role as center of the Hansa; Prussia's main interest, on the other hand, was the export of bulk products such as grain and timber to England, the Low Countries and later on Spain and Italy.[citation needed]

Frederick II, Elector of Brandenburg, tried to assert authority over the Hanseatic towns Berlin and Cölln in 1442 and blocked all Brandenburg towns from participating in Hanseatic diets. For some Brandenburg towns, this ended their Hanseatic involvement. In 1488, John Cicero, Elector of Brandenburg did the same to Stendal and Salzwedel in the Altmark.[48]: 34–35

Until 1394, Holland and Zeeland actively participated in the Hansa, but in 1395, their feudal obligations to Albert I, Duke of Bavaria prevented further cooperation. Consequently, their Hanseatic ties weakened, and their economic focus shifted. Between 1417 and 1432, this economic reorientation became even more pronounced as Holland and Zeeland gradually became part of the Burgundian State.

The city of Lübeck faced financial troubles in 1403, leading dissenting craftsmen to establish a supervising committee in 1405. This triggered a governmental crisis in 1408 when the committee rebelled and established a new town council. Similar revolts broke out in Wismar and Rostock, with new town councils established in 1410. The crisis was ended in 1418 by a compromise.[33]: 83–88 [undue weight? – discuss]

Eric of Pomerania succeeded Margaret in 1412 and sought to expand into Schleswig and Holstein levying tolls at the Øresund. Hanseatic cities were divided initially; Lübeck tried to appease Eric while Hamburg supported the Schauenburg counts against him. This led to the Danish-Hanseatic War (1426-1435) and the Bombardment of Copenhagen (1428). The Treaty of Vordingborg renewed the League's commercial privileges in 1435, but the Øresund tolls continued.

Eric of Pomerania was subsequently deposed and in 1438 Lübeck took control of the Øresund toll, which caused tensions with Holland and Zeeland.[33]: 89–91 [49]: 265 [50][51]: 171 The Sound tolls,[c] and a later attempt of Lübeck to exclude the English and Dutch merchants from Scania harmed the Scanian herring trade when the excluded regions began to develop their own herring industries.[34]: 157–158

In the Dutch–Hanseatic War (1438–1441), a privateer war mostly waged by Wendish towns, the merchants of Amsterdam sought and eventually won free access to the Baltic. Although the blockade of the grain trade hurt Holland and Zeeland more than Hanseatic cities, it was against Prussian interest to maintain it.[33]: 91

In 1454, the year of the marriage of Elisabeth of Austria to King-Grand Duke Casimir IV Jagiellon of Poland-Lithuania, the towns of the Prussian Confederation rose up against the dominance of the Teutonic Order and asked Casimir IV for help. Gdańsk (Danzig), Thorn and Elbing became part of the Kingdom of Poland, (from 1466 to 1569 referred to as Royal Prussia, region of Poland) by the Second Peace of Thorn.

Poland in turn was heavily supported by the Holy Roman Empire through family connections and by military assistance under the Habsburgs. Kraków, then the Polish capital, had a loose association with the Hansa.[52]: 93 The lack of customs borders on the River Vistula after 1466 helped to gradually increase Polish grain exports, transported down the Vistula, from 10,000 short tons (9,100 t) per year, in the late 15th century, to over 200,000 short tons (180,000 t) in the 17th century.[53] The Hansa-dominated maritime grain trade made Poland one of the main areas of its activity, helping Danzig to become the Hansa's largest city. Polish kings soon began to reduce the towns' political freedoms.[48]: 36

Beginning in the mid-15th century, the Griffin dukes of Pomerania were in constant conflict over control of the Pomeranian Hanseatic towns. While not successful at first, Bogislav X eventually subjugated Stettin and Köslin, curtailing the region's economy and independence.[48]: 35

A major Hansa economic advantage was its control of the shipbuilding market, mainly in Lübeck and Danzig. The League sold ships throughout Europe.[citation needed]

The economic crises of the late 15th century did not spare the Hansa. Nevertheless, its eventual rivals emerged in the form of territorial states. New vehicles of credit were imported from Italy.[citation needed]

When Flanders and Holland became part of the Duchy of Burgundy, Burgund Dutch and Prussian cities increasingly excluded Lübeck from their grain trade in the 15th and 16th century. Burgund Dutch demand for Prussian and Livonian grain grew in the late 15th century. These trade interests differed from Wendish interests, threatening political unity, but also showed a trade where the Hanseatic system was impractical.[30]: 198, 215–216 Hollandish freight costs were much lower than the Hansa's, and the Hansa were excluded as middlemen.[citation needed] After naval wars between Burgundy and the Hanseatic fleets, Amsterdam gained the position of leading port for Polish and Baltic grain from the late 15th century onwards.[citation needed]

Nuremberg in Franconia developed an overland route to sell formerly Hansa-monopolised products from Frankfurt via Nuremberg and Leipzig to Poland and Russia, trading Flemish cloth and French wine in exchange for grain and furs from the east. The Hansa profited from the Nuremberg trade by allowing Nurembergers to settle in Hanseatic towns, which the Franconians exploited by taking over trade with Sweden as well. The Nuremberger merchant Albrecht Moldenhauer was influential in developing the trade with Sweden and Norway, and his sons Wolf and Burghard Moldenhauer established themselves in Bergen and Stockholm, becoming leaders of the local Hanseatic activities.

King Edward IV of England reconfirmed the league's privileges in the Treaty of Utrecht despite the latent hostility, in part thanks to the significant financial contribution the League made to the Yorkist side during the Wars of the Roses of 1455–1487.[54]: 308–309 Tsar Ivan III of Russia closed the Hanseatic Kontor at Novgorod in 1494 and deported its merchants to Moscow, in an attempt to reduce Hanseatic influence on Russian trade.[55]: 145 At the time, only 49 traders were at the Peterhof.[56]: 99 The fur trade was redirected to Leipzig, taking out the Hansards;[36]: 54 while the Hanseatic trade with Russia moved to Riga, Reval, and Pleskau.[56]: 100 When the Peterhof reopened in 1514, Novgorod was no longer a trade hub.[54]: 182, 312 In the same period, the burghers of Bergen tried to develop an independent intermediate trade with the northern population, against the Hansards' obstruction.[39]: 144 The League's mere existence and its privileges and monopolies created economic and social tensions that often spilled onto rivalries between League members.

The development of transatlantic trade after the discovery of the Americas caused the remaining contours to decline, especially in Bruges, because it centered on other ports. It also changed business practice to short-term contracts and obsoleted the Hanseatic model of privileged guaranteed trade.[34]: 154

The trends of local feudal lords asserting control over towns and suppressing their autonomy, and of foreign rulers repressing Hanseatic traders continued in the next century.

In the Swedish War of Liberation 1521–1523, the Hanseatic League was successful in opposition to an economic conflict it had over the trade, mining, and metal industry in Bergslagen[57] (the main mining area of Sweden in the 16th century) with Jakob Fugger (industrialist in the mining and metal industry) and his unfriendly business take-over attempt. Fugger allied with his financially dependent pope Leo X, Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, and Christian II of Denmark/Norway. Both sides made costly investments in support of mercenaries to win the war. After the war, Gustav Vasa's Sweden and Frederick I's Denmark pursued independent policies and didn't support Lübeck's effort against Dutch trade.[40]: 113

However, Lübeck under Jürgen Wullenwever overextended in the Count's Feud in Scania and Denmark and lost influence in 1536 after Christian III's victory.[39]: 144 Lübeck's attempts at forcing competitors out of the Sound eventually alienated even Gustav Vasa.[40]: 113–114 Its influence in the Nordic countries began to decline.

The Hanseatic towns of Guelders were obstructed in the 1530s by Charles II, Duke of Guelders. Charles, a strict Catholic, objected to Lutheranism, in his words "Lutheran heresy", of Lübeck and other north German cities. This frustrated but did not end the towns' Hanseatic trade and a small resurgence came later.[58]

Later in the 16th century, Denmark-Norway took control of much of the Baltic. Sweden had regained control over its own trade, the Kontor in Novgorod had closed, and the Kontor in Bruges had become effectively moribund because the Zwin inlet was closing up.[34]: 132 Finally, the growing political authority of the German princes constrained the independence of Hanse towns.

The league attempted to deal with some of these issues: it created the post of syndic in 1556 and elected Heinrich Sudermann to the position, who worked to protect and extend the diplomatic agreements of the member towns. In 1557 and 1579, revised agreements spelled out the duties of towns and some progress was made. The Bruges Kontor moved to Antwerp in 1520[34]: 140–154 and the Hansa attempted to pioneer new routes. However, the league proved unable to prevent the growing mercantile competition.

In 1567, a Hanseatic League agreement reconfirmed previous obligations and rights of league members, such as common protection and defense against enemies.[59] The Prussian Quartier cities of Thorn, Elbing, Königsberg and Riga and Dorpat also signed. When pressed by the King of Poland–Lithuania, Danzig remained neutral and would not allow ships running for Poland into its territory. They had to anchor somewhere else, such as at Pautzke (Puck).

The Antwerp Kontor, moribund after the fall of the city, closed in 1593. In 1597 Queen Elizabeth I of England expelled the League from London, and the Steelyard closed and sequestered in 1598. The Kontor returned in 1606 under her successor, James I, but it could not recover.[54]: 341–343 The Bergen Kontor continued until 1754; of all the Kontore, only its buildings, the Bryggen, survive.

Not all states tried to suppress their cities' former Hanseatic links; the Dutch Republic encouraged its eastern former members to maintain ties with the remaining Hanseatic League. The States-General relied on those cities in diplomacy at the time of the Kalmar War.[32]: 123

The Thirty Years' War was destructive for the Hanseatic League and members suffered heavily from both the imperials, the Danes and the Swedes. In the beginning, Saxon and Wendish faced attacks because of the desire of Christian IV of Denmark to control the Elbe and Weser. Pomerania had a major population decline. Sweden took Bremen-Verden (excluding the city of Bremen), Swedish Pomerania (including Stralsund, Greifswald, Rostock) and Swedish Wismar, preventing their cities from participating in the League, and controlled the Oder, Weser, and Elbe, and could levy tolls on their traffic.[40]: 114–116 The league became increasingly irrelevant despite its inclusion in the Peace of Westphalia.[29]: 43

In 1666, the Steelyard burned in the Great Fire of London. The Kontor-manager sent a letter to Lübeck appealing for immediate financial assistance for a reconstruction. Hamburg, Bremen, and Lübeck called for a Hanseatic Day in 1669. Only a few cities participated and those who came were reluctant to contribute financially to the reconstruction. It was the last formal meeting, unbeknownst to any of the parties. This date is often taken in retrospect as the effective end date of the Hansa, but the League never formally disbanded. It silently disintegrated.[60]: 192 [10]: 2

The Hanseatic League, however, lived on in the public mind. Leopold I even requested Lübeck to call a Tagfahrt to rally support for him against the Turks.[60]: 192

Lübeck, Hamburg, and Bremen continued to attempt common diplomacy, although interests had diverged by the Peace of Ryswick.[60]: 192 Nonetheless, the Hanseatic Republics were able to jointly perform some diplomacy, such as a joint delegation to the United States in 1827, led by Vincent Rumpff; later the United States established a consulate to the Hanseatic and Free Cities from 1857 to 1862.[61] Britain maintained diplomats to the Hanseatic Cities until the unification of Germany in 1871. The three cities also had a common "Hanseatic" representation in Berlin until 1920.[60]: 192

Three kontors remained as, often unused, Hanseatic property after the League's demise, as the Peterhof had closed in the 16th century. Bryggen was sold to Norwegian owners in 1754. The Steelyard in London and the Oostershuis in Antwerp were long impossible to sell. The Steelyard was finally sold in 1852 and the Oostershuis, closed in 1593, was sold in 1862.[60]: 192 [54]: 341–343

Hamburg, Bremen, and Lübeck remained as the only members until the League's formal end in 1862, on the eve of the 1867 founding of the North German Confederation and the 1871 founding of the German Empire under Kaiser Wilhelm I. Despite its collapse, they cherished the link to the Hanseatic League. Until German reunification, these three cities were the only ones that retained the words "Hanseatic City" in their official German names. Hamburg and Bremen continue to style themselves officially as "free Hanseatic cities", with Lübeck named "Hanseatic City". For Lübeck in particular, this anachronistic tie to a glorious past remained important in the 20th century. In 1937, the Nazi Party revoked its imperial immediacy through the Greater Hamburg Act.[62] Since 1990, 24 other German cities have adopted this title.[63]

The Hanseatic League was a complex, loose-jointed constellation of protagonists pursuing their interests, which coincided in a shared program of economic domination in the Baltic region, and a by no means a monolithic organization or a 'state within a state'.[64]: 37–38 It gradually grew from a network of merchant guilds into a more formal association of cities, but never formed into a legal person.[56]: 91

League members were Low German-speaking, except for Dinant. Not all towns with Low German merchant communities were members (e.g., Emden, Memel (today Klaipėda), Viborg (today Vyborg), and Narva). However, Hansards also came from settlements without German town law—the premise for league membership was birth to German parents, subjection to German law, and commercial education. The league served to advance and defend its members' common interests: commercial ambitions such as enhancement of trade, and political ambitions such as ensuring maximum independence from the territorial rulers.[65]: 10–11

League decisions and actions were taken via a consensus-based procedure. If an issue arose, members were invited to participate in a central meeting, the Tagfahrt (Hanseatic Diet, "meeting ride", sometimes also referred to as Hansetag), that may have begun around 1300,[15]: 59 and were formalized since 1358 (or possibly 1356).[33]: 66–67 The member communities then chose envoys (Ratssendeboten) to represent their local consensus on the issue at the Diet. Not every community sent an envoy; delegates were often entitled to represent multiple communities. Consensus-building on local and Tagfahrt levels followed the Low Saxon tradition of Einung, where consensus was defined as the absence of protest: after a discussion, the proposals that gained sufficient support were dictated to the scribe and passed as binding Rezess if the attendees did not object; those favoring alternative proposals unlikely to get sufficient support remained silent during this procedure. If consensus could not be established on a certain issue, it was found instead in the appointment of league members empowered to work out a compromise.[65]: 70–72

The League was characterised by legal pluralism and the diets could not issue laws. But the cities cooperated to achieve limited trade regulation, such as measures against fraud, or worked together on a regional level. Attempts to harmonize maritime law yielded a series of ordinances in the 15th and 16th centuries. The most extensive maritime ordinance was the Ship Ordinance and Sea Law of 1614, but it may not have been enforced.[66]: 31, 37–38

A Hanseatic Kontor was a settlement of Hansards organized in the mid-14th century as a private corporation that had its treasury, court, legislation, and seal. They operated like an early stock exchange.[67]: 443–446 Kontors were first established to provide security, but also served to secure privileges and engage in diplomacy.[34]: 128–130, 134–135 The quality of goods was also examined at Kontors, increasing trade efficiency, and they served as bases to develop connections with local rulers and as sources of economic and political information.[56]: 91 [d] Most contours were also physical locations containing buildings that were integrated and segregated from city life to different degrees. The kontor of Bruges was an exception in this regard; it acquired buildings only as of the 15th century.[34]: 131–133 Like the guilds, the Kontore were usually led by Ältermänner ("eldermen", or English aldermen). The Stalhof, a special case, had a Hanseatic and an English alderman. In Novgorod the aldermen were replaced by a hofknecht in the 15th century.[54]: 100–101 The contours statutes were read aloud to the present merchants once a year.[34]: 131–133

In 1347 the Kontor of Bruges modified its statute to ensure an equal representation of League members. To that end, member communities from different regions were pooled into three circles (Drittel ("third [part]"): the Wendish and Saxon Drittel, the Westphalian and Prussian Drittel as well as the Gotlandian, Livonian and Swedish Drittel). Merchants from each Drittel chose two aldermen and six members of the Eighteen Men Council (Achtzehnmännerrat) to administer the Kontor for a set period.[56]: 91, 101 [34]: 138–139

In 1356, during a Hanseatic meeting in preparation for the first (or one of the first) Tagfahrt, the League confirmed this statute. All trader settlements including the Kontors were subordinated to the Diet's decisions around this time, and their envoys received the right to attend and speak at Diets, albeit without voting power.[56]: 91 [e]

The league gradually divided the organization into three constituent parts called Drittel (German thirds), as shown in the table below.[65]: 62–63 [68]: 55 [69][70]: 62–64

The Hansetag was the only central institution of the Hanseatic League. However, with the division into Drittel, the members of the respective subdivisions frequently held a Dritteltage ("Drittel meeting") to work out common positions which could then be presented at a Hansetag. On a more local level, league members also met, and while such regional meetings never crystalized into a Hanseatic institution, they gradually gained importance in the process of preparing and implementing the Diet's decisions.[71]: 55–57

From 1554, the division into Drittel was modified to reduce the circles' heterogeneity, to enhance the collaboration of the members on a regional level and thus to make the League's decision-making process more efficient.[72]: 217 The number of circles rose to four, so they were called Quartiere (quarters):[68]

This division was however not adopted by the Kontore, who, for their purposes (like Ältermänner elections), grouped League members in different ways (e.g., the division adopted by the Stalhof in London in 1554 grouped members into Dritteln, whereby Lübeck merchants represented the Wendish, Pomeranian Saxon, and several Westphalian towns, Cologne merchants represented the Cleves, Mark, Berg and Dutch towns, while Danzig merchants represented the Prussian and Livonian towns).[75]: 38–92

Various types of ships were used.

The most used type, and the most emblematic, was the cog. The cog was a multi-purpose clinker-built ship with a carvel bottom, a stern rudder, and a square rigged mast. Most cogs were privately owned and were also used as warships. Cogs were built in various sizes and specifications and were used on both the seas and rivers. They could be outfitted with castles starting from the thirteenth century. The cog was depicted on many seals and several coats of arms of Hanseatic cities, like Stralsund, Elbląg and Wismar. Several shipwrecks have been found. The most notable wreck is the Bremen cog.[37]: 35–36 It could carry a cargo of about 125 tons.[76]: 20

The hulk began to replace the cog by 1400 and cogs lost their dominance to them around 1450.[77]: 264

The Hulk was a bulkier ship that could carry larger cargo; Elbl estimates they could carry up to 500 tons by the 15th century. It could be clinker or carvel-built.[77]: 264 [78]: 64 No archeological evidence of a hulk has been found.

In 1464, Danzig acquired a French carvel ship through a legal dispute and renamed it the Peter von Danzig. It was 40 m long and had three masts, one of the largest ships of its time. Danzig adopted carvel construction around 1470.[55]: 44 Other cities shifted to carvels starting from this time. An example is the Jesus of Lübeck, later sold to England for use as a warship and slave ship.[79]

The galleonlike carvel warship Adler von Lübeck was constructed by Lübeck for military use against Sweden during the Northern Seven Years' War (1563–70), Llaunched in 1566, it was never put to military use after the Treaty of Stettin. It was the biggest ship of its day at 78 m long and had four masts, including a bonaventure mizzen. It served as a merchant ship until it was damaged in 1581 on a return voyage from Lisbon and broken up in 1588.[55]: 43–44 [80]

In the table below, the names listed in the column labeled Quarter have been summarised as follows:

The remaining column headings are as follows:

The kontore were the major foreign trading posts of the League, not cities that were Hanseatic members, and are listed in the hidden table below.

The vitten were significant foreign trading posts of the League in Scania, not cities that were Hanseatic members, they are argued by some to have been similar in status to the kontors,[34]: 157–158 and are listed in the hidden table below.

Academic historiography of the Hanseatic League is considered to begin with Georg Sartorius, who started writing his first work in 1795 and founded the liberal historiographical tradition about the League. The German conservative nationalist historiographical tradition was first published with F.W. Barthold's Geschichte der Deutschen Hansa of 1853/1854. The conservative view was associated with Little German ideology and came to predominate from the 1850s until the end of the First World War. Hanseatic history was used to justify a stronger German navy and conservative historians drew a link between the League and the rise of Prussia as the leading German state. This climate deeply influenced the historiography of the Baltic trade.[60]: 192–194 [30]: 203–204

Issues of social, cultural and economic history became more important in German research after the First World War. But leading historian Fritz Rörig also promoted a National Socialist perspective. After the Second World War the conservative nationalist view was discarded, allowing exchanges between German, Swedish and Norwegian historians on the Hanseatic League's role in Sweden and Norway. Views on the League were strongly negative in the Scandinavian countries, especially Denmark, because of associations with German privilege and supremacy.[123]: 68–69, 74 Philippe Dollinger's book The German Hansa became the standard work in the 1960s. At that time, the dominant perspective became Ahasver von Brandt's view of a loosely aligned trading network. Marxist historians in the GDR were split on whether the League was a "late feudal" or "proto-capitalist" phenomenon.[60]: 197–200

Two museums in Europe are dedicated to the history of the Hanseatic League: the European Hansemuseum in Lübeck and the Hanseatic Museum and Schøtstuene in Bergen.

From the 19th century, Hanseatic history was often used to promote a national cause in Germany. German liberals built a fictional literature around Jürgen Wullenwever, expressing fierce anti-Danish sentiment. Hanseatic subjects were used to propagate nation building, colonialism, fleet building and warfare, and the League was presented as a bringer of culture and pioneer of German expansion.[60]: 195–196

The preoccupation with a strong navy motivated German painters in the 19th century to paint supposedly Hanseatic ships. They used the traditions of maritime paintings and, not wanting Hanseatic ships to look unimpressive, ignored historical evidence to fictionalise cogs into tall two- or three-masted ships. The depictions were widely reproduced, such as on plates of Norddeutscher Lloyd. This misleading artistic tradition influenced public perception throughout the 20th century.[60]: 196–197

In the late 19th century, a social-critical view developed, where opponents of the League like the likedeelers were presented as heroes and liberators from economic oppression. This was popular from the end of the First World War into the 1930s, and survives in the Störtebeker Festival on Rügen, founded as the Rügenfestspiele by the GDR.[60]: 196

From the late 1970s, the Europeanness and cooperation of the Hanseatic League came to prominence in popular culture. It is associated with innovation, entrepreneurism and internationalness in economic circles.[60]: 199–203 In this way it often used for tourism, city branding and commercial marketing.[32]: 109 The League's unique governance structure has been identified as a precursor to the supranational model of the European Union.[124]

In 1979, Zwolle invited over 40 cities from West Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway with historic links to the Hanseatic League to sign the recesses of 1669, at Zwolle's 750 year city rights' anniversary in August of the next year.[125] In 1980, those cities established a "new Hanse" in Zwolle, named Städtebund Die Hanse (Union of Cities THE HANSA) in German and reinstituted the Hanseatic diets. This league is open to all former Hanseatic League members and cities that share a Hanseatic heritage.[126]

In 2012, the city league had 187 members. This included twelve Russian cities, most notably Novgorod, and 21 Polish cities. No Danish cities had joined the Union although several qualify.[60]: 199–200 The "new Hanse" fosters business links, tourism and cultural exchange.[126]

The headquarters of the New Hansa is in Lübeck, Germany.[126]

Dutch cities including Groningen, Deventer, Kampen, Zutphen and Zwolle, and a number of German cities including Bremen, Buxtehude, Demmin, Greifswald, Hamburg, Lübeck, Lüneburg, Rostock, Salzwedel, Stade, Stendal, Stralsund, Uelzen and Wismar now call themselves Hanse cities (the German cities' car license plates are prefixed H, e.g. –HB– for "Hansestadt Bremen").

Each year one of the member cities of the New Hansa hosts the Hanseatic Days of New Time international festival.

In 2006, King's Lynn became the first English member of the union of cities.[127] It was joined by Hull in 2012 and Boston in 2016.[128]

The New Hanseatic League was established in February 2018 by finance ministers from Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Sweden through the signing of a foundational document which set out the countries' "shared views and values in the discussion on the architecture of the EMU".[129]

The legacy of the Hansa is reflected in several names: the German airline Lufthansa (lit. "Air Hansa"); F.C. Hansa Rostock, nickamed the Kogge or Hansa-Kogge; Hansa-Park, one of the biggest theme parks in Germany; Hanze University of Applied Sciences in Groningen, Netherlands; Hanze oil production platform, Netherlands; the Hansa Brewery in Bergen and the Hanse Sail in Rostock; Hanseatic Trade Center in Hamburg; DDG Hansa, which was a major German shipping company from 1881 until its bankruptcy and takeover by Hapag-Lloyd in 1980; the district of New Hanza City in Riga, Latvia; and Hansabank in Estonia, which was rebranded as Swedbank.

[A] grant of about 1157 [...] conferred perpetual protection upon the homines et cives Colonienses. As long as they paid established dues they were to be treated as the king's men and no fresh charges would be levied on them without their consent. By this time they had some form of corporate organization with a headquarters in London [...].

To facilitate trade in foreign countries, the Hansa established counters (Kontore) [...]. [...] The counters operated as the equivalent of an early stock exchange.

The following cities were also connected with the League, but did not have representation in the Diet, nor responsibility: (...) Leghorn, Lisbon, London, Marseilles, Messina,Naples (...)