Вильгельм Завоеватель [a] (ок. 1028 [1] — 9 сентября 1087), иногда называемый Вильгельмом Бастардом , [2] [b] был первым нормандским королём Англии (как Вильгельм I ), правившим с 1066 года до своей смерти. Потомок Роллона , он был герцогом Нормандии (как Вильгельм II ) [3] с 1035 года. К 1060 году, после долгой борьбы, его власть в Нормандии была надёжной. В 1066 году, после смерти Эдуарда Исповедника , Вильгельм вторгся в Англию, приведя армию норманнов к победе над англосаксонскими войсками Гарольда Годвинсона в битве при Гастингсе , и подавил последующие английские восстания в ходе того, что стало известно как Нормандское завоевание . Оставшаяся часть его жизни была отмечена борьбой за укрепление своей власти над Англией и континентальными землями, а также трудностями в отношениях со старшим сыном Робертом Куртгёзом .

Уильям был сыном неженатого герцога Роберта I Нормандского и его любовницы Херлевы . Его незаконное положение и юность создали ему некоторые трудности после того, как он стал преемником своего отца, как и анархия, которая преследовала первые годы его правления. Во время его детства и юности члены нормандской аристократии сражались друг с другом, как за контроль над ребенком-герцогом, так и за свои собственные цели. В 1047 году Уильям подавил восстание и начал устанавливать свою власть над герцогством , процесс, который не был завершен до 1060 года. Его женитьба в 1050-х годах на Матильде Фландрской предоставила ему могущественного союзника в соседнем графстве Фландрия . К моменту своей женитьбы Уильям смог организовать назначение своих сторонников епископами и аббатами в нормандской церкви. Его консолидация власти позволила ему расширить свои горизонты, и он обеспечил контроль над соседним графством Мэн к 1062 году.

В 1050-х и начале 1060-х годов Вильгельм стал претендентом на трон Англии, который занимал бездетный Эдуард Исповедник, его двоюродный брат, которого он когда-то отстранил. Были и другие потенциальные претенденты, включая могущественного английского графа Гарольда Годвинсона, которого Эдуард назвал королем на смертном одре в январе 1066 года. Утверждая, что Эдуард ранее обещал ему трон и что Гарольд поклялся поддержать его притязания, Вильгельм построил большой флот и вторгся в Англию в сентябре 1066 года. Он решительно победил и убил Гарольда в битве при Гастингсе 14 октября 1066 года. После дальнейших военных усилий Вильгельм был коронован на Рождество 1066 года в Лондоне. Он принял меры для управления Англией в начале 1067 года, прежде чем вернуться в Нормандию. Последовало несколько неудачных восстаний, но к 1075 году власть Вильгельма в Англии была в основном надежной, что позволило ему провести большую часть своего правления в континентальной Европе .

Последние годы Вильгельма были отмечены трудностями в его континентальных владениях, проблемами с его сыном Робертом и угрозой вторжения в Англию датчан . В 1086 году он приказал составить Книгу Страшного суда , обзор, перечисляющий все земельные владения в Англии вместе с их владельцами до завоевания и нынешними владельцами. Он умер в сентябре 1087 года во время кампании в северной Франции и был похоронен в Кане . Его правление в Англии было отмечено строительством замков, поселением на земле новой нормандской знати и изменением состава английского духовенства. Он не пытался объединить свои владения в одну империю, а продолжал управлять каждой частью отдельно. После его смерти его земли были разделены: Нормандия досталась Роберту, а Англия досталась его второму выжившему сыну, Вильгельму Руфусу .

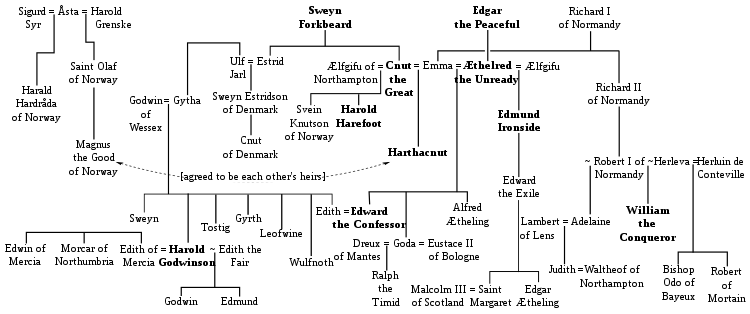

Скандинавы впервые начали совершать набеги на то, что стало Нормандией , в конце VIII века. Постоянное скандинавское поселение возникло до 911 года, когда Ролло , один из лидеров викингов, и король Франции Карл Простоватый достигли соглашения, уступив графство Руан Ролло. Земли вокруг Руана стали ядром более позднего герцогства Нормандия. [4] Нормандия могла использоваться в качестве базы, когда скандинавские нападения на Англию возобновились в конце X века, что ухудшило отношения между Англией и Нормандией. [5] Чтобы улучшить положение, король Этельред Неразумный взял Эмму , сестру Ричарда II, герцога Нормандии , в качестве своей второй жены в 1002 году. [6]

Датские набеги на Англию продолжались, и Этельред обратился за помощью к Ричарду, найдя убежище в Нормандии в 1013 году, когда король Дании Свейн I изгнал Этельреда и его семью из Англии. Смерть Свен в 1014 году позволила Этельреду вернуться домой, но сын Свена Кнут оспорил возвращение Этельреда. Этельред неожиданно умер в 1016 году, и Кнут стал королем Англии. Двое сыновей Этельреда и Эммы, Эдуард и Альфред , отправились в изгнание в Нормандию, а их мать, Эмма, стала второй женой Кнута. [7]

После смерти Кнута в 1035 году английский престол перешел к Гарольду Харефуту , его сыну от первой жены, в то время как Хардекнут , его сын от Эммы, стал королем Дании. Англия оставалась нестабильной. Альфред вернулся в Англию в 1036 году, чтобы навестить свою мать и, возможно, бросить вызов Гарольду как королю. Одна история приписывает графу Годвину Уэссекскому последовавшую за смертью Альфреда, но другие винят Гарольда. Эмма отправилась в изгнание во Фландрию , пока Хардекнут не стал королем после смерти Гарольда в 1040 году, а его сводный брат Эдвард последовал за Хардекнутом в Англию; Эдвард был провозглашен королем после смерти Хардекнута в июне 1042 года. [8] [c]

Вильгельм родился в 1027 или 1028 году в Фалезе , герцогстве Нормандии, скорее всего, ближе к концу 1028 года. [1] [9] [d] Он был единственным сыном Роберта I , сына Ричарда II. [e] Его мать, Герлева , была дочерью Фульберта Фалезского , который, возможно, был кожевником или бальзамировщиком. [10] Герлева, возможно, была членом герцогского дома, но не вышла замуж за Роберта. [2] Позже она вышла замуж за Герлюина де Контевиля , от которого у нее было два сына — Одо из Байё и граф Роберт де Мортен — и дочь, имя которой неизвестно. [f] Один из братьев Герлевы, Вальтер, стал сторонником и защитником Вильгельма во время его несовершеннолетия. [10] [g] У Роберта I также была дочь Аделаида от другой любовницы. [13]

Роберт I стал преемником своего старшего брата Ричарда III в качестве герцога 6 августа 1027 года. [1] Братья были в разногласиях по поводу престолонаследия, и смерть Ричарда была внезапной. Некоторые авторы обвиняли Роберта в убийстве Ричарда, правдоподобное, но теперь недоказуемое обвинение. [14] Обстановка в Нормандии была нестабильной, поскольку знатные семьи грабили Церковь, а Алан III Бретонский вел войну против герцогства, возможно, в попытке взять под контроль. К 1031 году Роберт собрал значительную поддержку от дворян, многие из которых стали видными деятелями при жизни Вильгельма. Среди них были дядя герцога Роберт , архиепископ Руанский , который изначально выступал против герцога; Осберн , племянник Гуннора , жены Ричарда I ; и Жильбер Брионнский , внук Ричарда I. [15] После своего восшествия на престол Роберт продолжал оказывать нормандскую поддержку английским принцам Эдуарду и Альфреду, которые все еще находились в изгнании на севере Франции. [2]

Роберт, возможно, был недолго помолвлен с дочерью короля Кнута, но брак не состоялся. Неясно, был бы Уильям вытеснен в герцогском престолонаследии, если бы у Роберта был законный сын. Более ранние герцоги были незаконнорожденными , и связь Уильяма с его отцом в герцогских хартиях, по-видимому, указывает на то, что Уильям считался наиболее вероятным наследником Роберта. [2] В 1034 году герцог решил отправиться в паломничество в Иерусалим . Хотя некоторые из его сторонников пытались отговорить его, он созвал совет в январе 1035 года и заставил собравшихся нормандских магнатов присягнуть на верность Уильяму как своему наследнику [2] [16] перед отъездом в Иерусалим. Он умер в начале июля в Никее , на обратном пути в Нормандию. [16]

Вильгельм столкнулся с несколькими проблемами, став герцогом, включая его незаконнорожденное рождение и его юный возраст: ему было то ли семь, то ли восемь лет. [17] [18] [h] Он пользовался поддержкой своего двоюродного деда, архиепископа Роберта, а также короля Генриха I Французского , что позволило ему унаследовать герцогство своего отца. [21] Поддержка, оказанная изгнанным английским принцам в их попытке вернуться в Англию в 1036 году, показывает, что опекуны нового герцога пытались продолжить политику его отца, [2] но смерть архиепископа Роберта в марте 1037 года устранила одного из главных сторонников Вильгельма, и Нормандия быстро погрузилась в хаос. [21]

Анархия в герцогстве продолжалась до 1047 года [22], и контроль над молодым герцогом был одним из приоритетов тех, кто боролся за власть. Сначала опекуном герцога был Алан Бретонский, но когда Алан умер либо в конце 1039 года, либо в октябре 1040 года, Гилберт Брионский взял на себя заботу о Вильгельме. Гилберт был убит в течение нескольких месяцев, а другой опекун, Турчетил, также был убит примерно во время смерти Гилберта. [23] Еще один опекун, Осберн, был убит в начале 1040-х годов в покоях Вильгельма, пока герцог спал. Говорят, что Уолтер, дядя Вильгельма по материнской линии, иногда был вынужден прятать молодого герцога в домах крестьян, [24] хотя эта история может быть приукрашена Ордериком Виталием . Историк Элеонора Сирл предполагает, что Уильям был воспитан с тремя кузенами, которые позже сыграли важную роль в его карьере — Уильямом ФицОсберном , Роджером де Бомоном и Роджером Монтгомери . [25] Хотя многие из нормандских дворян были вовлечены в свои собственные войны и распри во время несовершеннолетия Уильяма, виконты все еще признавали герцогское правительство, а церковная иерархия поддерживала Уильяма. [26]

Король Генрих продолжал поддерживать молодого герцога, [27] но в конце 1046 года противники Вильгельма объединились в восстании, сосредоточенном в Нижней Нормандии, во главе с Ги Бургундским при поддержке Найджела, виконта Котантена, и Ранульфа, виконта Бессена. Согласно историям, которые могут иметь легендарные элементы, была предпринята попытка схватить Вильгельма в Валони, но он сбежал под покровом темноты, ища убежища у короля Генриха. [28] В начале 1047 года Генрих и Вильгельм вернулись в Нормандию и одержали победу в битве при Валь-э-Дюн близ Кана , хотя подробностей сражения сохранилось немного. [29] Вильгельм Пуатье утверждал, что битва была выиграна в основном благодаря усилиям Вильгельма, но более ранние отчеты утверждают, что люди и руководство короля Генриха также сыграли важную роль. [2] Вильгельм захватил власть в Нормандии и вскоре после битвы провозгласил Божье перемирие по всему своему герцогству, пытаясь ограничить войну и насилие, ограничив дни года, в которые разрешалось сражаться. [30] Хотя битва при Валь-э-Дюне ознаменовала поворотный момент в контроле Вильгельма над герцогством, это не было концом его борьбы за господство над знатью. В период с 1047 по 1054 годы война была почти непрерывной, а менее значимые кризисы продолжались до 1060 года. [31]

Следующие усилия Вильгельма были направлены против Ги Бургундского, который отступил в свой замок в Брионе , который Вильгельм осадил. После долгих усилий герцогу удалось изгнать Ги в 1050 году. [32] Чтобы противостоять растущей мощи графа Анжуйского , Жоффруа Мартелла , [33] Вильгельм объединился с королем Генрихом в кампании против него, последнем известном сотрудничестве между ними. Им удалось захватить анжуйскую крепость, но больше ничего не добились. [34] Жоффруа попытался расширить свою власть на графство Мэн , особенно после смерти Гуго IV Мэна в 1051 году. Центральное место в контроле Мэна занимали владения семьи Беллем , которая держала Беллем на границе Мэна и Нормандии, а также крепости в Алансоне и Домфроне . Сюзереном Беллема был король Франции, но Домфронт находился под сюзереном Жоффруа Мартелла, а герцог Вильгельм был сюзереном Алансона. Семья Беллем, чьи земли были стратегически расположены между тремя их разными сюзеренами, смогла натравить их друг на друга и обеспечить себе фактическую независимость. [33]

После смерти Гуго Мэна Джеффри Мартель занял Мэн в ходе хода, оспариваемого Уильямом и королем Генрихом; в конце концов, им удалось вытеснить Джеффри из графства, и в процессе Уильям закрепил за собой крепости семьи Беллем в Алансоне и Домфроне. Таким образом, он смог утвердить свое господство над семьей Беллем и заставить их действовать в соответствии с нормандскими интересами. [35] Однако в 1052 году король и Джеффри Мартель объединили усилия против Уильяма, поскольку некоторые нормандские дворяне начали оспаривать растущую власть Уильяма. Изменение позиции Генриха, вероятно, было мотивировано желанием сохранить господство над Нормандией, которой теперь угрожало растущее господство Уильяма над его герцогством. [36] Уильям был вовлечен в военные действия против своих собственных дворян в течение всего 1053 года, [37] а также с новым архиепископом Руана Можем . [38]

В феврале 1054 года король и нормандские повстанцы начали двойное вторжение в герцогство. Генрих повел главный удар через графство Эврё , в то время как другое крыло под командованием сводного брата короля Одо вторглось в восточную Нормандию. [39] Вильгельм встретил вторжение, разделив свои силы на две части. Первая, которую он возглавлял, столкнулась с Генрихом. Вторая, в которую входили некоторые из тех, кто стал верными сторонниками Вильгельма, такие как Роберт, граф Э , Вальтер Жиффар , Роджер Мортемер и Вильгельм де Варенн , столкнулась с другой вторгшейся силой. Эта вторая сила разгромила захватчиков в битве при Мортемере . Помимо прекращения обоих вторжений, битва позволила церковным сторонникам герцога свергнуть архиепископа Може. Таким образом, Мортемер ознаменовал собой еще один поворотный момент в растущем контроле Вильгельма над герцогством, [40] хотя его конфликт с французским королем и графом Анжуйским продолжался до 1060 года. [41] Генрих и Жоффруа возглавили еще одно вторжение в Нормандию в 1057 году, но были разбиты Вильгельмом в битве при Варавилле . Это было последнее вторжение в Нормандию при жизни Вильгельма. В 1058 году Вильгельм вторгся в графство Дрё и взял Тильер-сюр-Авр и Тимерт . Генрих попытался вытеснить Вильгельма, но осада Тимерта затянулась на два года до смерти Генриха. Смерть графа Жоффруа и короля в 1060 году закрепила сдвиг в балансе сил в пользу Вильгельма. [42]

Одним из факторов в пользу Вильгельма был его брак с Матильдой Фландрской , дочерью графа Балдуина V Фландрского . Союз был устроен в 1049 году, но папа Лев IX запретил брак на Реймском соборе в октябре 1049 года. [i] Тем не менее брак состоялся в начале 1050-х годов, [44] [j], возможно, без одобрения папы. Согласно позднему источнику, который обычно не считается надежным, папское одобрение не было получено до 1059 года, но поскольку папско-нормандские отношения в 1050-х годах были в целом хорошими, и нормандское духовенство смогло посетить Рим в 1050 году без инцидентов, оно, вероятно, было получено раньше. [46] Папское одобрение брака, по-видимому, потребовало основания двух монастырей в Кане — одного Вильгельмом и одного Матильдой. [47] [k] Брак был важен для укрепления статуса Вильгельма, поскольку Фландрия была одной из самых могущественных французских территорий, связанной с французским королевским домом и германскими императорами. [46] Современные авторы считали этот брак, в результате которого родилось четыре сына и пять или шесть дочерей, удачным. [49]

Ни одного подлинного портрета Уильяма не было найдено; современные ему изображения на гобелене из Байё , а также на его печатях и монетах являются обычными представлениями, призванными утвердить его власть. [50] Существуют некоторые письменные описания его крепкого и крепкого внешнего вида с гортанным голосом. Он отличался отменным здоровьем до старости, хотя в более позднем возрасте он стал довольно толстым. [51] Он был достаточно силен, чтобы натягивать луки, которые другие не могли натянуть, и обладал большой выносливостью. [50] Джеффри Мартел описывал его как не имеющего себе равных бойца и наездника. [52] Исследование бедренной кости Уильяма , единственной кости, которая сохранилась, когда остальные его останки были уничтожены, показало, что его рост составлял приблизительно 5 футов 10 дюймов (1,78 м). [50]

Существуют записи о двух наставниках Уильяма в конце 1030-х и начале 1040-х годов, но степень его литературного образования неясна. Он не был известен как покровитель авторов, и мало доказательств того, что он спонсировал стипендии или интеллектуальную деятельность. [2] Orderic Vitalis отмечает, что Уильям пытался научиться читать на древнеанглийском языке в конце жизни, но он не смог уделить этому достаточно времени и быстро сдался. [53] Главным увлечением Уильяма, по-видимому, была охота. Его брак с Матильдой, по-видимому, был довольно нежным, и нет никаких признаков того, что он был ей неверен — необычно для средневекового монарха. Средневековые писатели критиковали Уильяма за его жадность и жестокость, но его личное благочестие повсеместно хвалили современники. [2]

Нормандское правительство при Вильгельме было похоже на правительство, существовавшее при предыдущих герцогах. Это была довольно простая административная система, построенная вокруг герцогского двора, [54] группы должностных лиц, включая управляющих , дворецких и маршалов . [55] Герцог постоянно путешествовал по герцогству, подтверждая хартии и собирая доходы. [56] Большая часть дохода поступала с герцогских земель, а также от пошлин и нескольких налогов. Этот доход собирала палата, одно из ведомств двора. [55]

Вильгельм поддерживал тесные отношения с церковью в своем герцогстве. Он принимал участие в церковных советах и сделал несколько назначений в нормандский епископат, включая назначение Маврилия архиепископом Руана. [57] Другим важным назначением было назначение сводного брата Вильгельма, Одо, епископом Байё в 1049 или 1050 году. [2] Он также полагался на духовенство в вопросах совета, включая Ланфранка , ненормандца, который стал одним из видных церковных советников Вильгельма с конца 1040-х по 1060-е годы. Вильгельм щедро жертвовал церкви; [57] с 1035 по 1066 год нормандская аристократия основала по меньшей мере двадцать новых монастырей, включая два монастыря Вильгельма в Кане, что стало заметным расширением религиозной жизни в герцогстве. [58]

В 1051 году бездетный король Англии Эдуард, по-видимому, выбрал Вильгельма своим преемником. [59] Вильгельм был внуком дяди Эдуарда по материнской линии, Ричарда II Нормандского. [59]

В «Англосаксонской хронике » в версии «D» говорится, что Вильгельм посетил Англию в конце 1051 года, возможно, чтобы обеспечить подтверждение престолонаследия [60] или, возможно, чтобы получить помощь в решении своих проблем в Нормандии. [61] Поездка маловероятна, учитывая, что Вильгельм в то время был занят войной с Анжу. Каковы бы ни были желания Эдуарда, вполне вероятно, что любые претензии Вильгельма натолкнутся на противодействие Годвина, графа Уэссекса , члена самой могущественной семьи в Англии. [60] Эдуард женился на Эдит , дочери Годвина, в 1043 году, и Годвин, по-видимому, был одним из главных сторонников притязаний Эдуарда на трон. [62] Однако к 1050 году отношения между королем и графом испортились, что привело к кризису в 1051 году, который привел к изгнанию Годвина и его семьи из Англии. Во время этого изгнания Эдуард предложил трон Вильгельму. [63] Годвин вернулся из изгнания в 1052 году с вооружёнными силами, и между королём и графом было достигнуто соглашение, согласно которому граф и его семья были возвращены на свои земли, а Роберт Жюмьежский , нормандец, которого Эдуард назначил архиепископом Кентерберийским , был заменен Стигандом , епископом Винчестерским . [64] Ни один английский источник не упоминает о предполагаемом посольстве архиепископа Роберта к Вильгельму, передающем обещание наследования, а два нормандских источника, которые упоминают об этом, Вильгельм Жюмьежский и Вильгельм Пуатье , неточны в своей хронологии относительно того, когда состоялся этот визит. [61]

Граф Герберт II из Мэна умер в 1062 году, и Вильгельм, который обручил своего старшего сына Роберта с сестрой Герберта Маргарет, заявил права на графство через своего сына. Местные дворяне сопротивлялись притязаниям, но Вильгельм вторгся и к 1064 году обеспечил контроль над территорией. [65] Вильгельм назначил нормандца епископом Ле-Мана в 1065 году. Он также позволил своему сыну Роберту Куртхозу принести присягу новому графу Анжуйскому, Жоффруа Бородатому . [66] Таким образом, западная граница Вильгельма была защищена, но его граница с Бретанью оставалась ненадежной. В 1064 году Вильгельм вторгся в Бретань в ходе кампании, детали которой остаются неясными. Однако ее результатом стала дестабилизация Бретани, заставив герцога Конана II сосредоточиться на внутренних проблемах, а не на расширении. Смерть Конана в 1066 году еще больше укрепила границы Вильгельма в Нормандии. Вильгельм также извлек выгоду из своей кампании в Бретани, заручившись поддержкой некоторых бретонских дворян, которые поддержали вторжение в Англию в 1066 году. [67]

Граф Годвин умер в 1053 году. Гарольд унаследовал графство своего отца, а другой сын, Тостиг , стал графом Нортумбрии . Другие сыновья получили графства позже: Гирт как граф Восточной Англии в 1057 году и Леофвин как граф Кент где-то между 1055 и 1057 годами. [68] Некоторые источники утверждают, что Гарольд принимал участие в бретонской кампании Вильгельма в 1064 году и поклялся поддерживать притязания Вильгельма на английский престол, [66] но ни один английский источник не сообщает об этой поездке, и неясно, произошла ли она на самом деле. Возможно, это была нормандская пропаганда, призванная дискредитировать Гарольда, который стал главным претендентом на престол короля Эдуарда. [69] Тем временем появился еще один претендент на трон — Эдуард Изгнанник , сын Эдмунда Железнобокого и внук Этельреда II, вернулся в Англию в 1057 году. Хотя он умер вскоре после возвращения, он привез с собой свою семью, в которую входили две дочери, Маргарет и Кристина , и сын, Эдгар Этелинг . [70] [l]

В 1065 году Нортумбрия восстала против Тостига , и мятежники выбрали Моркара , младшего брата Эдвина, графа Мерсии , в качестве графа. Гарольд, возможно, чтобы заручиться поддержкой Эдвина и Моркара в его стремлении к трону, поддержал мятежников и убедил короля Эдуарда заменить Тостига на Моркара. Тостиг отправился в изгнание во Фландрию со своей женой Джудит , которая была дочерью Балдуина IV, графа Фландрии . Эдуард был болен и умер 5 января 1066 года. Неясно, что именно произошло у смертного одра Эдуарда. Одна история, происходящая из Vita Ædwardi , биографии Эдуарда, утверждает, что его сопровождали его жена Эдит, Гарольд, архиепископ Стиганд и Роберт Фицвимарк , и что король назвал Гарольда своим преемником. Нормандские источники не оспаривают, что Гарольд был назван следующим королем, но заявляют, что клятва Гарольда и предыдущее обещание Эдуарда престола не могли быть изменены на смертном одре Эдуарда. Более поздние английские источники утверждали, что Гарольд был избран королем духовенством и магнатами Англии. [72]

Гарольд был коронован 6 января 1066 года в новом Вестминстерском аббатстве Эдуарда в нормандском стиле , хотя существуют некоторые разногласия относительно того, кто проводил церемонию. Английские источники утверждают, что церемонию провел Элдред , архиепископ Йоркский , в то время как нормандские источники утверждают, что коронацию провел Стиганд, которого папство считало неканоническим архиепископом. [73] Претензии Гарольда на трон не были полностью надежными, поскольку были и другие претенденты, возможно, включая его изгнанного брата Тостига. [74] [m] Король Норвегии Харальд Суровый также имел право на трон как дядя и наследник короля Магнуса I , который заключил пакт с Хардекнудом около 1040 года о том, что если Магнус или Хардекнуд умрут без наследников, то другой станет наследником. [78] Последним претендентом был Вильгельм Нормандский, против ожидаемого вторжения которого король Гарольд Годвинсон сделал большую часть своих приготовлений. [74]

Брат Гарольда Тостиг совершил пробные атаки вдоль южного побережья Англии в мае 1066 года, высадившись на острове Уайт, используя флот, предоставленный Балдуином Фландрским. Тостиг, по-видимому, получил небольшую местную поддержку, и дальнейшие набеги в Линкольншир и около Хамбера больше не имели успеха, поэтому он отступил в Шотландию. По словам нормандского писателя Вильгельма Жюмьежского, Вильгельм тем временем отправил посольство к королю Гарольду Годвинсону, чтобы напомнить Гарольду о его клятве поддержать притязания Вильгельма, хотя неясно, было ли это посольство на самом деле. Гарольд собрал армию и флот, чтобы отразить ожидаемое вторжение Вильгельма, разместив войска и корабли вдоль Ла-Манша большую часть лета. [74]

Вильгельм Пуатье описывает совет, созванный герцогом Вильгельмом, в котором автор дает отчет о дебатах между дворянами и сторонниками Вильгельма по поводу того, стоит ли рисковать вторжением в Англию. Хотя, вероятно, и проводилось какое-то формальное собрание, маловероятно, что какие-либо дебаты имели место: герцог к тому времени установил контроль над своими дворянами, и большинство собравшихся были бы заинтересованы в том, чтобы обеспечить себе свою долю наград от завоевания Англии. [79] Вильгельм Пуатье также сообщает, что герцог получил согласие папы Александра II на вторжение, а также папское знамя. Летописец также утверждал, что герцог заручился поддержкой Генриха IV, императора Священной Римской империи , и короля Дании Свена II . Однако Генрих был еще несовершеннолетним, и Свейн, скорее всего, поддержал Гарольда, который затем мог помочь Свену в борьбе с норвежским королем, поэтому к этим заявлениям следует относиться с осторожностью. Хотя Александр дал папское одобрение завоеванию после того, как оно удалось, ни один другой источник не утверждает о папской поддержке до вторжения. [n] [80] События после вторжения, включавшие покаяние, которое совершил Вильгельм, и заявления более поздних пап, косвенно подтверждают утверждение о папском одобрении. Чтобы разобраться с нормандскими делами, Вильгельм передал управление Нормандией в руки своей жены на время вторжения. [2]

В течение лета Вильгельм собрал армию и флот вторжения в Нормандии. Хотя утверждение Вильгельма Жюмьежского о том, что герцогский флот насчитывал 3000 кораблей, является явным преувеличением, он, вероятно, был большим и в основном построенным с нуля. Хотя Вильгельм Пуатье и Вильгельм Жюмьежский расходятся во мнениях о том, где был построен флот — Пуатье утверждает, что он был построен в устье реки Див , в то время как Жюмьеж утверждает, что он был построен в Сен-Валери-сюр-Сомм — оба согласны, что в конечном итоге он отплыл из Валери-сюр-Сомм. Флот перевозил силы вторжения, включавшие, помимо войск с территорий Вильгельма Нормандии и Мэна, большое количество наемников, союзников и добровольцев из Бретани , северо-восточной Франции и Фландрии, а также меньшее количество из других частей Европы. Хотя армия и флот были готовы к началу августа, неблагоприятные ветры удерживали корабли в Нормандии до конца сентября. Вероятно, были и другие причины задержки Уильяма, включая разведывательные отчеты из Англии, показывающие, что силы Гарольда были развернуты вдоль побережья. Уильям предпочел бы отложить вторжение до тех пор, пока он не сможет совершить беспрепятственную высадку. [80] Гарольд держал свои силы в состоянии боевой готовности все лето, но с наступлением сезона сбора урожая он распустил свою армию 8 сентября. [81]

Тостиг Годвинсон и Харальд Суровый вторглись в Нортумбрию в сентябре 1066 года и разгромили местные силы под командованием Моркара и Эдвина в битве при Фулфорде около Йорка . Король Гарольд получил известие об их вторжении и двинулся на север, разгромив захватчиков и убив Тостига и Сурового 25 сентября в битве при Стэмфорд-Бридже . [78] Нормандский флот наконец отплыл два дня спустя, высадившись в Англии в заливе Певенси 28 сентября. Затем Вильгельм двинулся в Гастингс , в нескольких милях к востоку, где построил замок в качестве базы для операций. Оттуда он опустошал внутренние районы и ждал возвращения Гарольда с севера, отказываясь отплывать далеко от моря, его линии связи с Нормандией. [81]

После победы над Харальдом Суровым и Тостигом, Гарольд оставил большую часть своей армии на севере, включая Моркара и Эдвина, и двинулся с оставшейся частью на юг, чтобы справиться с угрозой вторжения норманнов. [81] Вероятно, он узнал о высадке Вильгельма, когда путешествовал на юг. Гарольд остановился в Лондоне примерно на неделю, прежде чем отправиться в Гастингс, поэтому вполне вероятно, что он провел около недели в своем походе на юг, в среднем проходя около 27 миль (43 километра) в день, [82] на расстояние около 200 миль (320 километров). [83] Хотя Гарольд пытался застать норманнов врасплох, разведчики Вильгельма сообщили герцогу о прибытии англичан. Точные события, предшествовавшие битве, неясны, с противоречивыми отчетами в источниках, но все согласны с тем, что Вильгельм вывел свою армию из своего замка и двинулся на врага. [84] Гарольд занял оборонительную позицию на вершине холма Сенлак (современный Баттл, Восточный Суссекс ), примерно в 6 милях (9,7 километрах) от замка Уильяма в Гастингсе. [85]

Битва началась около 9 утра 14 октября и продолжалась весь день. Хотя общий план известен, точные события затемнены противоречивыми отчетами. [86] Хотя численность с каждой стороны была примерно одинаковой, у Вильгельма была как кавалерия, так и пехота, включая множество лучников, в то время как у Гарольда были только пехотинцы и несколько, если таковые вообще были, лучников. [87] Английские солдаты выстроились в стену щитов вдоль хребта и поначалу были настолько эффективны, что армия Вильгельма была отброшена назад с тяжелыми потерями. Некоторые из бретонских войск Вильгельма запаниковали и бежали, а некоторые английские войска, по-видимому, преследовали бегущих бретонцев, пока сами не были атакованы и уничтожены нормандской кавалерией. Во время бегства бретонцев среди нормандских войск распространились слухи о том, что герцог был убит, но Вильгельму удалось сплотить свои войска. Были сымитированы еще два отступления нормандцев, чтобы выманить англичан на преследование и подвергнуть их повторным атакам нормандской кавалерии. [88] Доступные источники более запутанны относительно событий, произошедших днем, но, по-видимому, решающим событием была смерть Гарольда, о которой рассказывают разные истории. Уильям Жюмьежский утверждал, что Гарольд был убит герцогом. Гобелен из Байё, как утверждается, показывает смерть Гарольда от стрелы в глаз, но это может быть более поздняя переделка гобелена, чтобы соответствовать историям XII века, в которых Гарольд был убит стрелой, ранившей его в голову. [89]

Тело Гарольда было опознано на следующий день после битвы, либо по его доспехам, либо по отметинам на теле. Английские убитые, включая некоторых братьев Гарольда и его хускарлов , были оставлены на поле битвы. Гита Торкельсдоттир , мать Гарольда, предложила герцогу вес тела своего сына в золоте за него, но ее предложение было отклонено. [o] Вильгельм приказал бросить тело в море, но было ли это сделано, неясно. Уолтемское аббатство , которое основал Гарольд, позже утверждало, что его тело было тайно похоронено там. [93]

Уильям, возможно, надеялся, что англичане сдадутся после его победы, но этого не произошло. Вместо этого некоторые представители английского духовенства и магнаты выдвинули Эдгара Этелинга на пост короля, хотя их поддержка Эдгара была лишь умеренной. Немного подождав, Уильям захватил Дувр , части Кента и Кентербери , а также отправил войска на захват Винчестера , где находилась королевская казна. [94] Эти захваты обеспечили тыловые районы Уильяма и его линию отступления в Нормандию, если это было необходимо. [2] Затем Уильям двинулся в Саутуарк , через Темзу из Лондона, куда он прибыл в конце ноября. Затем он повел свои войска вокруг юга и запада Лондона, сжигая по пути. Наконец, он пересек Темзу в Уоллингфорде в начале декабря. Там Стиганд подчинился Уильяму, и когда герцог вскоре двинулся в Беркхэмстед , Эдгар Этелинг, Моркар, Эдвин и Элдред также подчинились. Затем Вильгельм послал войска в Лондон, чтобы построить замок; он был коронован в Вестминстерском аббатстве на Рождество 1066 года. [94]

William remained in England after his coronation and tried to reconcile the native magnates. The remaining earls – Edwin (of Mercia), Morcar (of Northumbria), and Waltheof (of Northampton) – were confirmed in their lands and titles.[95] Waltheof was married to William's niece Judith, daughter of his half-sister Adelaide,[96] and a marriage between Edwin and one of William's daughters was proposed. Edgar the Ætheling also appears to have been given lands. Ecclesiastical offices continued to be held by the same bishops as before the invasion, including the uncanonical Stigand.[95] But the families of Harold and his brothers lost their lands, as did some others who had fought against William at Hastings.[97] By March, William was secure enough to return to Normandy, but he took with him Stigand, Morcar, Edwin, Edgar, and Waltheof. He left his half-brother Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux, in charge of England along with another influential supporter, William fitzOsbern, the son of his former guardian.[95] Both men were also named to earldoms – fitzOsbern to Hereford (or Wessex) and Odo to Kent.[2] Although he put two Normans in overall charge, he retained many of the native English sheriffs.[97] Once in Normandy the new English king went to Rouen and the Abbey of Fecamp,[95] and then attended the consecration of new churches at two Norman monasteries.[2]

While William was in Normandy, a former ally, Eustace, the Count of Boulogne, invaded at Dover but was repulsed. English resistance had also begun, with Eadric the Wild attacking Hereford and revolts at Exeter, where Harold's mother Gytha was a focus of resistance.[98] FitzOsbern and Odo found it difficult to control the native population and undertook a programme of castle-building to maintain their hold on the kingdom.[2] William returned to England in December 1067 and marched on Exeter, which he besieged. The town held out for 18 days. After it fell to William he built a castle to secure his control. Harold's sons were meanwhile raiding the southwest of England from a base in Ireland. Their forces landed near Bristol but were defeated by Eadnoth. By Easter, William was at Winchester, where he was soon joined by his wife Matilda, who was crowned in May 1068.[98]

In 1068 Edwin and Morcar rose in revolt, supported by Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria. Orderic Vitalis states that Edwin's reason for revolting was that the proposed marriage between himself and one of William's daughters had not taken place, but another reason probably included the increasing power of fitzOsbern in Herefordshire, which affected Edwin's power within his own earldom. The king marched through Edwin's lands and built Warwick Castle. Edwin and Morcar submitted, but William continued on to York, building York and Nottingham Castles before returning south. On his southbound journey, he began constructing Lincoln, Huntingdon, and Cambridge Castles. William placed supporters in charge of these new fortifications – among them William Peverel at Nottingham and Henry de Beaumont at Warwick – then returned to Normandy late in 1068.[98]

Early in 1069, Edgar the Ætheling revolted and attacked York. Although William returned to York and built another castle, Edgar remained free, and in the autumn he joined up with King Sweyn.[p] The Danish king had brought a large fleet to England and attacked not only York but Exeter and Shrewsbury. York was captured by the combined forces of Edgar and Sweyn. Edgar was proclaimed king by his supporters. William responded swiftly, ignoring a continental revolt in Maine, and symbolically wore his crown in the ruins of York on Christmas Day 1069. He then bought off the Danes. He marched to the River Tees, ravaging the countryside as he went. Edgar, having lost much of his support, fled to Scotland,[99] where King Malcolm III was married to Edgar's sister Margaret.[100] Waltheof, who had joined the revolt, submitted, along with Gospatric, and both were allowed to retain their lands. William marched over the Pennines during the winter and defeated the remaining rebels at Shrewsbury before building Chester and Stafford Castles. This campaign, which included the burning and destruction of part of the countryside that the royal forces marched through, is usually known as the "Harrying of the North"; it was over by April 1070, when William wore his crown ceremonially for Easter at Winchester.[99]

While at Winchester in 1070, William met with three papal legates – John Minutus, Peter, and Ermenfrid of Sion – who had been sent by the pope. The legates ceremonially crowned William during the Easter court.[101] The historian David Bates sees this coronation as the ceremonial papal "seal of approval" for William's conquest.[2] The legates and the king then held a series of ecclesiastical councils dedicated to reforming and reorganising the English church. Stigand and his brother, Æthelmær, the Bishop of Elmham, were deposed from their bishoprics. Some of the native abbots were also deposed, both at the council held near Easter and at a further one near Whitsun. The Whitsun council saw the appointment of Lanfranc as the new Archbishop of Canterbury, and Thomas of Bayeux as the new Archbishop of York, to replace Ealdred, who had died in September 1069.[101] William's half-brother Odo perhaps expected to be appointed to Canterbury, but William probably did not wish to give that much power to a family member.[q] Another reason for the appointment may have been pressure from the papacy to appoint Lanfranc.[102] Norman clergy were appointed to replace the deposed bishops and abbots, and at the end of the process, only native English bishops remained in office, along with several continental prelates appointed by Edward the Confessor.[101] In 1070 William also founded Battle Abbey, a new monastery at the site of the Battle of Hastings, partly as a penance for the deaths in the battle and partly as a memorial to the dead.[2] At an ecclesiastical council held in Lillebonne in 1080, he was confirmed in his ultimate authority over the Norman church.[103]

Although Sweyn had promised to leave England, he returned in early 1070, raiding along the Humber and East Anglia toward the Isle of Ely, where he joined up with Hereward the Wake, a local thegn. Hereward's forces captured and looted Peterborough Abbey. William was able to secure the departure of Sweyn and his fleet in 1070,[104] allowing him to return to the continent to deal with troubles in Maine, where the town of Le Mans had revolted in 1069. Another concern was the death of Count Baldwin VI of Flanders in July 1070, which led to a succession crisis as his widow, Richilde, was ruling for their two young sons, Arnulf and Baldwin. Her rule was contested by Robert, Baldwin's brother. Richilde proposed marriage to William fitzOsbern, who was in Normandy, and fitzOsbern accepted. But after he was killed in February 1071 at the Battle of Cassel, Robert became count. He was opposed to King William's power on the continent, thus the Battle of Cassel upset the balance of power in northern France and cost William an important supporter.[105]

In 1071 William defeated the last rebellion of the north. Earl Edwin was betrayed by his own men and killed, while William built a causeway to subdue the Isle of Ely, where Hereward the Wake and Morcar were hiding. Hereward escaped, but Morcar was captured, deprived of his earldom, and imprisoned. In 1072 William invaded Scotland, defeating Malcolm, who had recently invaded the north of England. William and Malcolm agreed to peace by signing the Treaty of Abernethy, and Malcolm probably gave up his son Duncan as a hostage for the peace. Perhaps another stipulation of the treaty was the expulsion of Edgar the Ætheling from Malcolm's court.[106] William then turned his attention to the continent, returning to Normandy in early 1073 to deal with the invasion of Maine by Fulk le Rechin, the Count of Anjou. With a swift campaign, William seized Le Mans from Fulk's forces, completing the campaign by 30 March 1073. This made William's power more secure in northern France, but the new count of Flanders accepted Edgar the Ætheling into his court. Robert also married his half-sister Bertha to King Philip I of France, who was opposed to Norman power.[107]

William returned to England to release his army from service in 1073 but quickly returned to Normandy, where he spent all of 1074.[108] He left England in the hands of his supporters, including Richard fitzGilbert and William de Warenne,[109] as well as Lanfranc.[110] William's ability to leave England for an entire year was a sign that he felt that his control of the kingdom was secure.[109] While William was in Normandy, Edgar the Ætheling returned to Scotland from Flanders. The French king, seeking a focus for those opposed to William's power, proposed that Edgar be given the castle of Montreuil-sur-Mer on the Channel, which would have given Edgar a strategic advantage against William.[111] However, Edgar was forced to submit to William shortly thereafter, and he returned to William's court.[108][r] Philip, although thwarted in this attempt, turned his attentions to Brittany, leading to a revolt in 1075.[111]

In 1075, during William's absence, Ralph de Gael, the Earl of Norfolk, and Roger de Breteuil, the Earl of Hereford, conspired to overthrow William in the "Revolt of the Earls".[110] Ralph was at least part Breton and had spent most of his life prior to 1066 in Brittany, where he still had lands.[113] Roger was a Norman, son of William fitzOsbern, but had inherited less authority than his father held.[114] Ralph's authority seems also to have been less than his predecessors in the earldom, and this was likely the cause of his involvement in the revolt.[113]

The exact reason for the rebellion is unclear. It was launched at the wedding of Ralph to a relative of Roger, held at Exning in Suffolk. Waltheof, the earl of Northumbria, although one of William's favourites, was involved, and some Breton lords were ready to rebel in support of Ralph and Roger. Ralph also requested Danish aid. William remained in Normandy while his men in England subdued the revolt. Roger was unable to leave his stronghold in Herefordshire because of efforts by Wulfstan, the Bishop of Worcester, and Æthelwig, the Abbot of Evesham. Ralph was bottled up in Norwich Castle by the combined efforts of Odo of Bayeux, Geoffrey de Montbray, Richard fitzGilbert, and William de Warenne. Ralph eventually left Norwich in the control of his wife and left England, ending up in Brittany. Norwich was besieged and surrendered, with the garrison allowed to go to Brittany. Meanwhile, the Danish king's brother, Cnut, had finally arrived in England with a fleet of 200 ships, but Norwich had already surrendered. The Danes raided along the coast before returning home.[110] William returned to England later in 1075 to deal with the Danish threat, leaving his wife Matilda in charge of Normandy. He celebrated Christmas at Winchester and dealt with the aftermath of the rebellion.[115] Roger and Waltheof were kept in prison, where Waltheof was executed in May 1076. Before this, William had returned to the continent, where Ralph had continued the rebellion from Brittany.[110]

Earl Ralph had secured control of the castle at Dol, and in September 1076 William advanced into Brittany and laid siege to the castle. King Philip of France later relieved the siege and defeated William at the Battle of Dol in 1076, forcing him to retreat to Normandy. Although this was William's first defeat in battle, it did little to change things. An Angevin attack on Maine was defeated in late 1076 or 1077, with Count Fulk le Rechin wounded in the unsuccessful attack. More serious was the retirement of Simon de Crépy, the Count of Amiens, to a monastery. Before he became a monk, Simon handed his county of the Vexin over to King Philip. The Vexin was a buffer state between Normandy and the lands of the French king, and Simon had been a supporter of William.[s] William was able to make peace with Philip in 1077 and secured a truce with Count Fulk in late 1077 or early 1078.[116]

In late 1077 or early 1078 trouble began between William and his eldest son, Robert. Although Orderic Vitalis describes it as starting with a quarrel between Robert and his younger brothers William and Henry, including a story that the quarrel was started when William and Henry threw water at Robert, it is much more likely that Robert was feeling powerless. Orderic relates that he had previously demanded control of Maine and Normandy and had been rebuffed. The trouble in 1077 or 1078 resulted in Robert leaving Normandy accompanied by a band of young men, many of them the sons of William's supporters. Included among them were Robert of Belleme, William de Breteuil, and Roger, the son of Richard fitzGilbert. This band went to the castle at Remalard, where they proceeded to raid into Normandy. The raiders were supported by many of William's continental enemies.[117] William immediately attacked the rebels and drove them from Remalard, but King Philip gave them the castle at Gerberoi, where they were joined by new supporters. William then laid siege to Gerberoi in January 1079. After three weeks, the besieged forces sallied from the castle and took the besiegers by surprise. William was unhorsed by Robert and was only saved from death by an Englishman, Toki son of Wigod, who was himself killed.[118] William's forces were forced to lift the siege, and the king returned to Rouen. By 12 April 1080, William and Robert had reached an accommodation, with William once more affirming that Robert would receive Normandy when he died.[119]

Word of William's defeat at Gerberoi stirred up difficulties in northern England. In August and September 1079 King Malcolm of Scots raided south of the River Tweed, devastating the land between the River Tees and the Tweed in a raid that lasted almost a month. The lack of Norman response appears to have caused the Northumbrians to grow restive, and in the spring of 1080 they rebelled against the rule of Walcher, the Bishop of Durham and Earl of Northumbria. Walcher was killed on 14 May 1080, and the king dispatched his half-brother Odo to deal with the rebellion.[120] William departed Normandy in July 1080,[121] and in the autumn his son Robert was sent on a campaign against the Scots. Robert raided into Lothian and forced Malcolm to agree to terms, building the 'new castle' at Newcastle upon Tyne while returning to England.[120] The king was at Gloucester for Christmas 1080 and at Winchester for Whitsun in 1081, ceremonially wearing his crown on both occasions. A papal embassy arrived in England during this period, asking that William do fealty for England to the papacy, a request that he rejected.[121] William also visited Wales in 1081, although the English and the Welsh sources differ on the purpose of the visit. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that it was a military campaign, but Welsh sources record it as a pilgrimage to St Davids in honour of Saint David. William's biographer David Bates argues that the former explanation is more likely: the balance of power had recently shifted in Wales and William would have wished to take advantage of this to extend Norman power. By the end of 1081, William was back on the continent, dealing with disturbances in Maine. Although he led an expedition into Maine, the result was instead a negotiated settlement arranged by a papal legate.[122]

Sources for William's actions between 1082 and 1084 are meagre. According to the historian David Bates, this probably means that little of note happened, and that because William was on the continent, there was nothing for the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to record.[123] In 1082, William ordered the arrest of his half-brother Odo. The exact reasons are unclear, as no contemporary author recorded what caused the quarrel between the half-brothers. Orderic Vitalis later recorded that Odo had aspirations to become pope and that Odo had attempted to persuade some of William's vassals to join Odo in an invasion of southern Italy. This would have been considered tampering with the king's authority over his vassals, which William would not have tolerated. Although Odo remained in confinement for the rest of William's reign, his lands were not confiscated. In 1083, William's son Robert rebelled once more with support from the French king. A further blow was the death of Queen Matilda on 2 November 1083. William was always described as close to his wife, and her death would have added to his problems.[124]

Maine continued to be difficult, with a rebellion by Hubert de Beaumont-au-Maine, probably in 1084. Hubert was besieged in his castle at Sainte-Suzanne by William's forces for at least two years, but he eventually made peace with the king and was restored to favour. William's movements during 1084 and 1085 are unclear – he was in Normandy at Easter 1084 but may have been in England before then to collect the danegeld assessed that year for the defence of England against an invasion by King Cnut IV of Denmark. Although English and Norman forces remained on alert throughout 1085 and into 1086, the invasion threat was ended by Cnut's death in July 1086.[125]

As part of his efforts to secure England, William ordered many castles, keeps, and mottes built – among them the central keep of the Tower of London, the White Tower. These fortifications allowed Normans to retreat into safety when threatened with rebellion and allowed garrisons to be protected while they occupied the countryside. The early castles were simple earth and timber constructions, later replaced with stone structures.[127]

At first, most of the newly settled Normans kept household knights and did not settle their retainers with fiefs of their own, but gradually these household knights came to be granted lands of their own, a process known as subinfeudation. William also required his newly created magnates to contribute fixed quotas of knights towards not only military campaigns but also castle garrisons. This method of organising the military forces was a departure from the pre-Conquest English practice of basing military service on territorial units such as the hide.[128]

By William's death, after weathering a series of rebellions, most of the native Anglo-Saxon aristocracy had been replaced by Norman and other continental magnates. Not all of the Normans who accompanied William in the initial conquest acquired large amounts of land in England. Some appear to have been reluctant to take up lands in a kingdom that did not always appear pacified. Although some of the newly rich Normans in England came from William's close family or from the upper Norman nobility, others were from relatively humble backgrounds.[129] William granted some lands to his continental followers from the holdings of one or more specific Englishmen; at other times, he granted a compact grouping of lands previously held by many different Englishmen to one Norman follower, often to allow for the consolidation of lands around a strategically placed castle.[130]

The medieval chronicler William of Malmesbury says that the king also seized and depopulated many miles of land (36 parishes), turning it into the royal New Forest to support his enthusiastic enjoyment of hunting. Modern historians have concluded that the New Forest depopulation was greatly exaggerated. Most of the New Forest comprises poor agricultural lands, and archaeological and geographic studies have shown that it was likely sparsely settled when it was turned into a royal forest.[131] William was known for his love of hunting, and he introduced the forest law into areas of the country, regulating who could hunt and what could be hunted.[132]

After 1066, William did not attempt to integrate his separate domains into one unified realm with one set of laws. His seal from after 1066, of which six impressions still survive, was made for him after he conquered England and stressed his role as king, while separately mentioning his role as duke.[t] When in Normandy, William acknowledged that he owed fealty to the French king, but in England no such acknowledgement was made – further evidence that the various parts of William's lands were considered separate. The administrative machinery of Normandy, England, and Maine continued to exist separate from the other lands, with each one retaining its own forms. For example, England continued the use of writs, which were not known on the continent. Also, the charters and documents produced for the government in Normandy differed in formulas from those produced in England.[133]

William took over an English government that was more complex than the Norman system. England was divided into shires or counties, which were further divided into either hundreds or wapentakes. Each shire was administered by a royal official called a sheriff, who roughly had the same status as a Norman viscount. A sheriff was responsible for royal justice and collecting royal revenue.[55] To oversee his expanded domain, William was forced to travel even more than he had as duke. He crossed back and forth between the continent and England at least 19 times between 1067 and his death. William spent most of his time in England between the Battle of Hastings and 1072; after that, he spent the majority of his time in Normandy.[134][u] Government was still centred on William's household; when he was in one part of his realms, decisions would be made for other parts of his domains and transmitted through a communication system that made use of letters and other documents. William also appointed deputies who could make decisions while he was absent, especially if the absence was expected to be lengthy. Usually, this was a member of William's close family – frequently his half-brother Odo or his wife Matilda. Sometimes deputies were appointed to deal with specific issues.[135]

William continued the collection of danegeld, a land tax. This was an advantage for William and the only universal tax collected by western European rulers during this period. It was an annual tax based on the value of landholdings and could be collected at differing rates. Most years saw the rate of two shillings per hide, but in crises, it could be increased to as much as six shillings per hide.[136] Coinage across his domains continued to be minted in different cycles and styles. English coins were generally of high silver content, with high artistic standards, and were required to be re-minted every three years. Norman coins had a much lower silver content, were often of poor artistic quality, and were rarely re-minted. In England, no other coinage was allowed, while on the continent other coinage was considered legal tender. Nor is there evidence that many English pennies were circulating in Normandy, which shows little attempt to integrate the monetary systems of England and Normandy.[133]

Besides taxation, William's large landholdings throughout England strengthened his rule. As King Edward's heir, he controlled all of the former royal lands. He also retained control of much of the lands of Harold and his family, which made the king the largest secular landowner in England by a wide margin.[v]

At Christmas 1085, William ordered the compilation of a survey of the landholdings held by himself and by his vassals throughout his kingdom, organised by counties. It resulted in a work now known as the Domesday Book. The listing for each county gives the holdings of each landholder, grouped by owners. The listings describe the holding, who owned the land before the Conquest, its value, its tax assessment, and usually the number of peasants, ploughs, and any other resources the holding had. Towns were listed separately. All the English counties south of the River Tees and River Ribble are included. The whole work seems to have been mostly completed by 1 August 1086, when the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that William received the results and that all the chief magnates swore the Salisbury Oath, a renewal of their oaths of allegiance.[138] William's motivation in ordering the survey is unclear, but it probably had several purposes, such as making a record of feudal obligations and justifying increased taxation.[2]

William left England towards the end of 1086. Following his arrival back on the continent he married his daughter Constance to Duke Alan of Brittany, in furtherance of his policy of seeking allies against the French kings. William's son Robert, still allied with the French king, appears to have been active in stirring up trouble, enough so that William led an expedition against the French Vexin in July 1087. While seizing Mantes, William either fell ill or was injured by the pommel of his saddle.[139] He was taken to the priory of Saint Gervase at Rouen, where he died on 9 September 1087.[2] Knowledge of the events preceding his death is confused because there are two different accounts. Orderic Vitalis preserves a lengthy account, complete with speeches made by many of the principals, but this is likely more of an account of how a king should die than of what actually happened. The other, the De obitu Willelmi, or On the Death of William, has been shown to be a copy of two 9th-century accounts with names changed.[139]

.jpg/440px-Church_of_Saint-Étienne_interior_(2).jpg)

William left Normandy to Robert, and the custody of England was given to William's second surviving son, also called William, on the assumption that he would become king. The youngest son, Henry, received money. After entrusting England to his second son, the elder William sent the younger William back to England on 7 or 8 September, bearing a letter to Lanfranc ordering the archbishop to aid the new king. Other bequests included gifts to the Church and money to be distributed to the poor. William also ordered that all of his prisoners be released, including his half-brother Odo.[139]

Disorder followed William's death; everyone who had been at his deathbed left the body at Rouen and hurried off to attend to their own affairs. Eventually, the clergy of Rouen arranged to have the body sent to Caen, where William had desired to be buried in his foundation of the Abbaye-aux-Hommes. The funeral, attended by the bishops and abbots of Normandy as well as his son Henry, was disturbed by a citizen of Caen who alleged that his family had been illegally despoiled of the land on which the church was built. After hurried consultations, the allegation was shown to be true, and the man was compensated. A further indignity occurred when the corpse was lowered into the tomb. The corpse was too large for the space, and when attendants forced the body into the tomb it burst, spreading a disgusting odour throughout the church.[140]

William's grave is marked by a marble slab with a Latin inscription dating from the early 19th century. The tomb has been disturbed several times since 1087, the first time in 1522 when the grave was opened on orders from the papacy. The intact body was restored to the tomb at that time, but in 1562, during the French Wars of Religion, the grave was reopened and the bones scattered and lost, with the exception of one thigh bone. This lone relic was reburied in 1642 with a new marker, which was replaced 100 years later with a more elaborate monument. This tomb was again destroyed during the French Revolution but was eventually replaced with the current ledger stone.[141][w]

The immediate consequence of William's death was a war between his sons Robert and William over control of England and Normandy.[2] Even after the younger William's death in 1100 and the succession of his youngest brother Henry as king, Normandy and England remained contested between the brothers until Robert's capture by Henry at the Battle of Tinchebray in 1106. The difficulties over the succession led to a loss of authority in Normandy, with the aristocracy regaining much of the power they had lost to the elder William. His sons also lost much of their control over Maine, which revolted in 1089 and managed to remain mostly free of Norman influence thereafter.[143]

The impact on England of William's conquest was profound; changes in the Church, aristocracy, culture, and language of the country have persisted into modern times. The Conquest brought the kingdom into closer contact with France and forged ties that lasted throughout the Middle Ages. Another consequence of William's invasion was the sundering of the formerly close ties between England and Scandinavia. William's government blended elements of the English and Norman systems into a new one that laid the foundations of the later medieval English kingdom.[144] How abrupt and far-reaching the changes were is still a matter of debate among historians, with some such as Richard Southern claiming that the Conquest was the single most radical change in European history between the Fall of Rome and the 20th century. Others, such as H. G. Richardson and G. O. Sayles, see the changes as much less radical.[145] The historian Eleanor Searle describes William's invasion as "a plan that no ruler but a Scandinavian would have considered".[146]

William's reign has caused historical controversy since before his death. William of Poitiers wrote glowingly of William's reign and its benefits, but the obituary notice for William in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle condemns William in harsh terms.[145] During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, Archbishop Matthew Parker saw the Conquest as having corrupted a purer English Church, which Parker attempted to restore. During the 17th and 18th centuries, some historians and lawyers saw William's reign as imposing a "Norman yoke" on the native Anglo-Saxons, an argument that continued during the 19th century with further elaborations along nationalistic lines. These controversies have led to William being seen by some historians either as one of the creators of England's greatness or as inflicting one of the greatest defeats in English history. Others have viewed him as an enemy of the English constitution, or alternatively as its creator.[147]

William and his wife Matilda had at least nine children.[49] The birth order of the sons is clear, but no source gives the relative order of birth of the daughters.[2]

There is no evidence of any illegitimate children born to William.[155]