Испанская колонизация Америки началась в 1493 году на карибском острове Эспаньола (ныне Гаити и Доминиканская Республика) после первого плавания генуэзского мореплавателя Христофора Колумба в 1492 году по лицензии королевы Изабеллы I Кастильской . Эти заморские территории Испанской империи находились под юрисдикцией короны Кастильской до тех пор, пока последняя территория не была потеряна в 1898 году . Испанцы считали густонаселенные коренные народы важным экономическим ресурсом, а территорию, на которую претендовали, потенциально производящей огромное богатство для отдельных испанцев и короны. Религия сыграла важную роль в испанском завоевании и присоединении коренных народов, приведя их в католическую церковь мирным путем или силой. Корона создала гражданские и религиозные структуры для управления обширной территорией. Испанские мужчины и женщины селились в наибольшем количестве там, где было густонаселенное коренное население и имелись ценные ресурсы для добычи . [1]

Испанская империя претендовала на юрисдикцию над Новым Светом в Карибском море, а также над Северной и Южной Америкой, за исключением Бразилии, уступленной Португалии по Тордесильясскому договору . Другие европейские державы, включая Англию, Францию и Голландскую республику, завладели территориями, первоначально заявленными Испанией. Хотя заморские территории, находящиеся под юрисдикцией испанской короны, теперь обычно называются «колониями», этот термин не использовался до второй половины XVIII века. Процесс испанского заселения, теперь называемый «колонизацией» и «колониальной эпохой», — это термины, оспариваемые учеными Латинской Америки [2] [3] [4] и в более общем плане. [5]

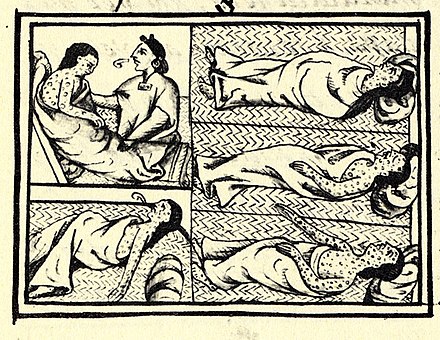

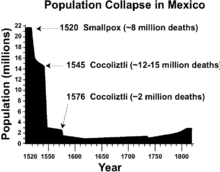

По оценкам, в период с 1492 по 1832 год в Америке поселилось в общей сложности 1,86 миллиона испанцев, а еще 3,5 миллиона иммигрировали в эпоху после обретения независимости (1850–1950 гг.); оценка составляет 250 000 человек в XVI веке и большая часть в XVIII веке, поскольку иммиграция поощрялась новой династией Бурбонов . [6] Коренное население резко сократилось примерно на 80% в первые полтора столетия после путешествий Колумба, в основном из-за распространения инфекционных заболеваний . Были внедрены практики принудительного труда и рабства для добычи ресурсов, а также принудительного переселения в новые деревни и более поздние миссии . [7] Встревоженная резким сокращением численности коренного населения и сообщениями об эксплуатации их труда поселенцами, корона ввела законы для защиты своих недавно обращенных в христианство вассалов из числа коренных народов. Европейцы импортировали рабов-африканцев в ранние поселения Карибского бассейна, чтобы заменить местную рабочую силу, а рабы и свободные африканцы были частью населения колониальной эпохи. Смешанное расовое население casta возникло в период испанского правления.

В начале 19 века испано-американские войны за независимость привели к отделению большей части Испанской Америки и созданию независимых государств. Под властью короны продолжали находиться Куба и Пуэрто-Рико , а также Филиппины , которые были потеряны Соединенными Штатами в 1898 году после испано-американской войны , положившей конец их правлению в Америке.

Расширение территории Испании произошло при католических монархах Изабелле I Кастильской и ее муже Фердинанде II Арагонском , чей брак ознаменовал начало испанской власти за пределами Пиренейского полуострова . Они проводили политику совместного правления своими королевствами и создали начальный этап единой испанской монархии , завершенный при монархах династии Бурбонов XVIII века. Первым расширением территории стало завоевание мусульманского эмирата Гранада 1 января 1492 года, кульминация христианской Реконкисты Пиренейского полуострова, удерживаемого мусульманами с 711 года. 31 марта 1492 года католический монарх приказал изгнать евреев из Испании, которые отказались принять христианство. 12 октября 1492 года генуэзский мореплаватель Христофор Колумб высадился в Западном полушарии, и в 1493 году началось постоянное испанское поселение в Америке. [8]

Кастилия и Арагон управлялись совместно своими монархами, но они оставались отдельными королевствами. Когда католические монархи официально одобрили планы путешествия Колумба по достижению «Индии» на Запад, финансирование поступило от королевы Кастилии. Прибыль от испанской экспедиции текла в Кастилию. Королевство Португалия санкционировало серию путешествий вдоль побережья Африки, и когда они обогнули южную оконечность, смогли доплыть до Индии и дальше на восток. Испания стремилась к такому же богатству и санкционировала путешествие Колумба на Запад. После того, как произошло испанское поселение в Карибском море, Испания и Португалия официально оформили раздел мира между собой в Тордесильясском договоре 1494 года . [9] Глубоко набожная Изабелла видела расширение суверенитета Испании неразрывно связанным с евангелизацией нехристианских народов, так называемое «духовное завоевание» с военным завоеванием. Папа Александр VI в папском указе от 4 мая 1493 года Inter caetera разделил права на земли в Западном полушарии между Испанией и Португалией при условии, что они будут распространять христианство. [10] Эти формальные соглашения между Испанией, Португалией и папой были проигнорированы другими европейскими державами, при этом французы, англичане и голландцы захватили территории в Карибском море и в Северной Америке, на которые претендовала Испания, но которые фактически не были урегулированы. Претензии Португалии на часть Южной Америки по Тордесильясскому договору привели к созданию португальской колонии Бразилия. Хотя во время правления Карла V Испанская империя была первой, которую называли « империей, над которой никогда не заходит солнце », при Филиппе II постоянная колонизация Филиппинских островов сделала это явно верным.

Испанскую экспансию иногда кратко описывали как мотивированную «золотом, славой, Богом», то есть поиском материального богатства, усилением позиций завоевателей и короны и распространением христианства за счет других религиозных традиций. При распространении испанского суверенитета на заморские территории полномочия на экспедиции ( entradas ) по открытию, завоеванию и заселению принадлежали монархии. [11] Экспедиции требовали разрешения короны, которая излагала условия такой экспедиции. Практически все экспедиции после путешествий Колумба, которые финансировались короной Кастилии, проводились за счет руководителя экспедиции и ее участников. Хотя часто участников, конкистадоров , теперь называют «солдатами», они не были оплачиваемыми солдатами в рядах армии, а скорее солдатами удачи , которые присоединялись к экспедиции с ожиданием получить от нее прибыль. Руководитель экспедиции, аделантадо, был старшим человеком с материальным достатком и положением, который мог убедить корону выдать ему лицензию на экспедицию. Он также должен был привлечь участников экспедиции, которые ставили на карту свои собственные жизни и скудные состояния в ожидании успеха экспедиции. Руководитель экспедиции закладывал большую долю капитала в предприятие, которое во многом функционировало как коммерческая фирма. После успеха экспедиции военная добыча делилась пропорционально сумме, которую участник изначально поставил, причем руководитель получал наибольшую долю. Участники предоставляли свои собственные доспехи и оружие, а те, у кого была лошадь, получали две доли, одну для себя, вторую в знак признания ценности лошади как орудия войны. [12] [13] Для эпохи завоевания широко известны имена двух испанцев, которые возглавляли завоевания двух коренных империй, Эрнана Кортеса , лидера экспедиции, участвовавшей в завоевании империи ацтеков , и Франсиско Писарро , лидера завоевания инков в Перу. Испанские завоеватели воспользовались соперничеством коренных народов, чтобы заключить союзы с группами, которые видели в этом преимущество для своих собственных целей. Это наиболее отчетливо видно на примере завоевания империи ацтеков с союзом города-государства науа Тласкала против империи ацтеков , что принесло им и их потомкам долгосрочные выгоды.

Образцы первых испанских поселений в Карибском море сохранились там и оказали длительное влияние на Испанскую империю. [14] До самой смерти Колумб был убежден, что он достиг Азии, Индии. Из-за этого ошибочного восприятия испанцы называли коренные народы Америки «индейцами» ( indios ), объединяя множество цивилизаций, групп и людей в одну категорию. Испанское королевское правительство называло свои заморские владения «Индией», пока его империя не распалась в девятнадцатом веке.

В Карибском море, поскольку там не было интегрированной коренной цивилизации, такой как в Мексике и Перу, не было масштабного испанского завоевания коренных народов, но было коренное сопротивление испанской колонизации. Колумб совершил четыре путешествия в Вест-Индию , поскольку монархи предоставили Колумбу обширные полномочия по управлению этой неизвестной частью мира. Корона Кастилии финансировала большую часть его трансатлантических путешествий, модель, которую они не повторяли в других местах. Эффективное испанское поселение началось в 1493 году, когда Колумб привез скот, семена, сельскохозяйственное оборудование. Первое поселение Ла-Навидад , грубый форт, построенный во время его первого путешествия в 1492 году, был заброшен к тому времени, когда он вернулся в 1493 году. Затем он основал поселение Ла-Исабела на острове, который они назвали Эспаньола (теперь разделен на Гаити и Доминиканскую Республику ).

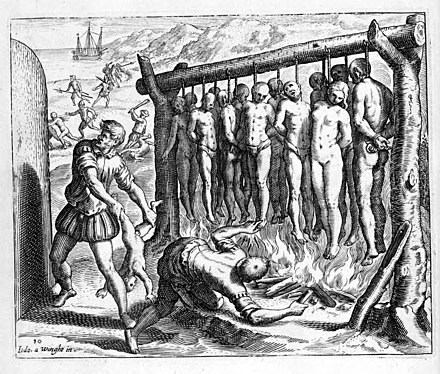

Исследования испанцами других островов Карибского моря и того, что оказалось материковой частью Южной и Центральной Америки, заняли их более двух десятилетий. Колумб обещал короне, что регион, который он теперь контролировал, хранит огромные сокровища в виде золота и специй. Испанские поселенцы изначально обнаружили относительно плотные популяции коренных народов, которые были земледельцами, живущими в деревнях, управляемых лидерами, не входящими в более крупную интегрированную политическую систему. Испанцы рассматривали эти популяции как источник рабочей силы, для их эксплуатации, для снабжения своих собственных поселений продуктами питания, но, что более важно для испанцев, для добычи полезных ископаемых или производства другого ценного товара для обогащения Испании. Труд плотных популяций таино выделялся в качестве грантов испанским поселенцам в учреждении, известном как энкомьенда , где отдельные поселения коренных народов присуждались отдельным испанцам. На ранних островах было найдено поверхностное золото, и владельцы энкомьенд заставляли коренных жителей работать на его промывке. По всем практическим соображениям это было рабство. Королева Изабелла положила конец формальному рабству, объявив коренное население вассалами короны, но эксплуатация коренного труда испанцами продолжалась. Население таино на Эспаньоле выросло с сотен тысяч или миллионов — оценки ученых сильно разнятся — но в середине 1490-х годов они были практически уничтожены. Болезни и переутомление, нарушение семейной жизни и сельскохозяйственного цикла (что привело к серьезной нехватке продовольствия для испанцев, зависящих от них) быстро уничтожили коренное население. С точки зрения испанцев, их источник рабочей силы и жизнеспособность их собственных поселений были под угрозой. После краха популяции таино на Эспаньоле испанцы начали совершать набеги на коренные поселения на близлежащих островах, включая Кубу , Пуэрто-Рико и Ямайку , чтобы поработить это население, повторив там демографическую катастрофу. Имена двух индейских вождей ( касиков ), восставших против испанской колонизации, Энрикильо и Атуэй в Доминиканской Республике (Эспаньола), стали важными. [16]

Доминиканский монах Антонио де Монтесинос осудил испанскую жестокость и насилие в проповеди 1511 года, которая дошла до нас в трудах доминиканского монаха Бартоломе де лас Касаса . В 1542 году доминиканский монах Бартоломе де лас Касас написал осуждающий отчет об этой демографической катастрофе, «Краткий отчет об уничтожении Индий» . Он был быстро переведен на английский язык и стал основой для антииспанских сочинений, известных под общим названием « Черная легенда» . [17] Лас Касас провел свою долгую жизнь, пытаясь защитить коренное население и заручиться поддержкой испанской короны в установлении для него защиты, что наиболее заметно в принятии Новых законов 1542 года, ограничивающих наследование испанцами энкомьенд .

За первыми исследованиями материка испанцами последовала фаза внутренних экспедиций и завоеваний. В 1500 году на острове Кубагуа в Венесуэле был основан город Нуэва-Кадис , а затем Алонсо де Охеда основал Санта-Крус на территории современного полуострова Гуахира . Кумана в Венесуэле была первым постоянным поселением, основанным европейцами на материковой части Америки [18] в 1501 году францисканскими монахами , но из-за успешных нападений коренных народов ее пришлось несколько раз перестраивать, пока в 1569 году не основал Диего Эрнандес де Серпа . Испанцы основали Сан-Себастьян-де-Ураба в 1509 году, но покинули его в течение года. Есть косвенные доказательства того, что первым постоянным испанским поселением на материке, основанным в Америке, была Санта-Мария-ла-Антигуа-дель-Дарьен [19] .

Испанцы провели более 25 лет в Карибском море, где их первоначальные большие надежды на ослепительное богатство уступили место продолжающейся эксплуатации исчезающего коренного населения, истощению местных золотых приисков, началу выращивания тростникового сахара как экспортного продукта и принудительной миграции рабов-африканцев в качестве рабочей силы. Испанцы продолжали расширять свое присутствие в регионе Карибского моря с помощью экспедиций. Одна была Франсиско Эрнандеса де Кордовы в 1517 году, другая Хуана де Грихальвы в 1518 году, которые принесли многообещающие новости о возможностях там. [20] [21] Даже к середине 1510-х годов западные Карибские острова были в значительной степени неисследованы испанцами. Эрнан Кортес , поселенец с хорошими связями на Кубе, получил разрешение в 1519 году от губернатора Кубы сформировать экспедицию для исследования только этого далекого западного региона. Эта экспедиция должна была войти в мировую историю. Карибские острова стали менее важными для заморской колонизации Испании, но оставались важными стратегически и экономически, особенно острова Куба и Эспаньола. Более мелкие острова, на которые претендовала Испания, были потеряны для англичан и голландцев, а Франция заняла половину Эспаньолы и основала сахаропроизводящую колонию Сан-Доминго , а также захватила другие острова. [22] [23]

_Painting.jpg/440px-The_Meeting_of_Cortés_and_Moctezuma_(Conquest_of_Mexico)_Painting.jpg)

С испанской экспансией в центральную Мексику под руководством завоевателя Эрнана Кортеса и завоеванием Империи ацтеков (1519-1521) испанские исследователи смогли найти богатство в масштабах, на которые они давно надеялись. В отличие от контактов испанцев с коренным населением Карибского бассейна, которые включали ограниченные вооруженные бои и иногда участие коренных союзников, завоевание центральной Мексики было длительным и требовало значительного числа коренных союзников, которые решили участвовать в разгроме Империи ацтеков в своих собственных целях. Завоевание Империи ацтеков включало объединенные усилия армий многих коренных союзников, возглавляемых небольшим испанским отрядом конкистадоров. Ацтеки не правили империей в общепринятом смысле, а были правителями конфедерации десятков городов-государств и других политических образований; статус каждого из них варьировался от жестко подчиненного до тесно связанного. Испанцы убедили лидеров вассалов ацтеков и Тласкалу (город-государство, никогда не завоеванный ацтеками) объединиться с ними против ацтеков. С помощью таких методов испанцы собрали огромную силу из тысяч, возможно, десятков тысяч коренных воинов. Записи о завоевании центральной Мексики включают рассказы руководителя экспедиции Эрнана Кортеса, Берналя Диаса дель Кастильо и других испанских конкистадоров, коренных союзников из городов-государств альтепетль Тласкалы, Тескоко и Уэшоцинко. Кроме того, коренные рассказы были написаны побежденными из столицы ацтеков, Теночтитлана , случай, когда историю писали не победители. [24] [25] [26]

Захват императора ацтеков Монтесумы II Кортесом не был блестящим новаторским ходом, но он был частью сценария, который испанцы разработали во время своего пребывания на Карибах. Состав экспедиции был стандартным: старший лидер и участвующие мужчины, вкладывающиеся в предприятие с полным ожиданием вознаграждения, если они не потеряют свои жизни. Поиски Кортесом союзников из числа коренных народов были типичной тактикой ведения войны: разделяй и властвуй. Но союзники из числа коренных народов могли многое выиграть, сбросив правление ацтеков. Для союзников испанцев из Тлашкалы их решающая поддержка принесла им прочное политическое наследие в современную эпоху — мексиканское государство Тлашкала. [27] [28]

Завоевание центральной Мексики спровоцировало дальнейшие испанские завоевания, следуя образцу завоеванных и консолидированных регионов, являющихся отправной точкой для дальнейших экспедиций. Их часто возглавляли второстепенные лидеры, такие как Педро де Альварадо . Более поздние завоевания в Мексике были длительными кампаниями с менее быстрыми результатами, чем завоевание империи ацтеков. Испанское завоевание Юкатана , испанское завоевание Гватемалы , завоевание пурепеча Мичоакана, война на западе Мексики и война чичимеков на севере Мексики расширили испанский контроль над территорией и коренным населением, простирающимися на тысячи миль. [29] [30] [31] [32] Только после завоевания империи инков , которое использовало похожую тактику и началось в 1532 году, завоевание ацтеков было сопоставимо по масштабам как территории, так и сокровищ.

_-_Pizarro_Seizing_the_Inca_of_Peru_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/440px-Millais,_John_Everett_(Sir)_-_Pizarro_Seizing_the_Inca_of_Peru_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

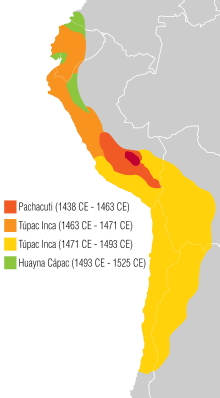

В 1532 году в битве при Кахамарке группа испанцев под командованием Франсиско Писарро и их союзников из числа местных индейцев Анд устроили засаду и захватили императора Атауальпу из империи инков . Это был первый шаг в долгой кампании, которая заняла десятилетия борьбы, чтобы покорить самую могущественную империю в Америке. В последующие годы Испания распространила свое господство на империю цивилизации инков .

Испанцы воспользовались недавней гражданской войной между фракциями двух братьев-императоров Атауальпы и Уаскара , а также враждой коренных народов, покоренных инками, таких как уанка , чачапойя и каньяри . В последующие годы конкистадоры и их союзники из числа коренных народов расширили контроль над Большими Андами. Вице-королевство Перу было создано в 1542 году. Последняя цитадель инков была завоевана испанцами в 1572 году.

Перу была последней территорией на континенте под властью Испании, которая закончилась 9 декабря 1824 года в битве при Аякучо (на Кубе и в Пуэрто-Рико испанское правление продолжалось до 1898 года).

[В Чили] зима длится четыре месяца, не больше, и в эти дни, за исключением четверти луны, когда один или два дня идет дождь, во все остальные дни светит такое прекрасное солнце...

Чили была исследована испанцами, обосновавшимися в Перу, где испанцы нашли плодородную почву и мягкий климат привлекательными. Народ мапуче в Чили, которого испанцы называли арауканами , сопротивлялся яростно. Испанцы основали поселение Чили в 1541 году, основанное Педро де Вальдивией . [33]

Южная колонизация Чили испанцами прекратилась после завоевания архипелага Чилоэ в 1567 году. Считается, что это было результатом все более сурового климата на юге и отсутствия густонаселенного и оседлого коренного населения, среди которого испанцы могли бы поселиться во фьордах и каналах Патагонии . [34] К югу от реки Био-Био мапуче успешно отменили колонизацию, уничтожив семь городов в 1599–1604 годах. [33] [35] Эта победа мапуче заложила основу для установления испано-мапуческой границы под названием Ла-Фронтера . В пределах этой границы город Консепсьон взял на себя роль «военной столицы» Чили, находящейся под управлением испанцев. [36] Чили с враждебным коренным населением, без очевидных полезных ископаемых или других пригодных для эксплуатации ресурсов и с незначительной стратегической ценностью представляло собой окраину колониальной испанской Америки, географически ограниченную Андами на востоке, Тихим океаном на западе и коренными народами на юге. [33]

Между 1537 и 1543 годами шесть [ требуется ссылка ] испанских экспедиций вошли в высокогорную Колумбию, завоевали Конфедерацию муисков и основали Новое королевство Гранада (исп. Nuevo Reino de Granada ). Гонсало Хименес де Кесада был ведущим конкистадором, а его брат Эрнан был вторым по должности. [37] Им управлял президент Аудиенсии Боготы , и он включал в себя территорию, соответствующую в основном современной Колумбии и частям Венесуэлы . Первоначально конкистадоры организовали его как генерал-капитанство в вице-королевстве Перу . Корона учредила аудиенцию в 1549 году. В конечном итоге королевство стало частью вице-королевства Новая Гранада сначала в 1717 году, а затем окончательно в 1739 году. После нескольких попыток создания независимых государств в 1810-х годах королевство и вице-королевство полностью прекратили свое существование в 1819 году с созданием Великой Колумбии . [38]

Венесуэлу впервые посетили европейцы в 1490-х годах, когда Колумб контролировал регион, и регион был источником местных рабов для испанцев на Кубе и Эспаньоле с момента уничтожения испанцами местного коренного населения. Постоянных поселений было немного, но испанцы заселили прибрежные острова Кубагуа и Маргарита , чтобы разрабатывать жемчужные залежи. История Западной Венесуэлы приняла нетипичное направление в 1528 году, когда первый монарх Габсбургов Испании Карл I предоставил права на колонизацию немецкой банковской семье Вельзеров . Карл стремился быть избранным императором Священной Римской империи и был готов заплатить любую цену, чтобы добиться этого. Он стал очень обязанным немецким банковским семьям Вельзеров и Фуггеров . Чтобы погасить свои долги перед Вельзерами, он предоставил им право колонизировать и эксплуатировать западную Венесуэлу с условием, что они найдут два города с 300 поселенцами в каждом и построят укрепления. Они основали колонию Кляйн-Венедиг в 1528 году. Они основали города Коро и Маракайбо . Они были агрессивны в том, чтобы заставить свои инвестиции окупиться, оттолкнув как коренное население, так и испанцев. Карл отозвал грант в 1545 году, положив конец эпизоду немецкой колонизации . [39] [40]

Аргентина не была завоевана или позднее эксплуатировалась так же, как центральная Мексика или Перу, поскольку коренное население было редким, а драгоценных металлов или других ценных ресурсов не было. Хотя сегодня Буэнос-Айрес в устье Рио-де-ла-Плата является крупным мегаполисом, он не представлял интереса для испанцев, и поселение 1535–36 годов потерпело неудачу и было заброшено к 1541 году. Педро де Мендоса и Доминго Мартинес де Ирала , возглавлявшие первоначальную экспедицию, отправились вглубь страны и основали Асунсьон, Парагвай , который стал базой испанцев. Второе (и постоянное) поселение было основано в 1580 году Хуаном де Гараем , который прибыл по реке Парана из Асунсьона , ныне столицы Парагвая . [41] Исследования из Перу привели к основанию Тукумана на территории современной северо-западной Аргентины. [42]

Большая часть того, что сейчас является Южными Соединенными Штатами, была захвачена Испанией, часть из них, по крайней мере, исследовалась испанцами, начиная с начала 1500-х годов, и были основаны некоторые постоянные поселения. Испанские исследователи заявили права на земли для короны в современных штатах Алабама, Аризона, Каролина , Колорадо, Флорида, Джорджия, Миссисипи, Нью-Мексико, Техас и Калифорния. [43] Пуэрто-Рико также было колонизировано испанцами в эту эпоху, что стало причиной самого раннего контакта между африканцами и тем, что впоследствии стало Соединенными Штатами (через свободного черного конкистадора Хуана Гарридо ). Свободные и порабощенные африканцы были характерной чертой Новой Испании на протяжении всего колониального периода. [44]

Один из колонистов, завоевавших Пуэрто-Рико, Хуан Понсе де Леон , обычно считается первым европейцем, увидевшим Флориду в 1513 году. [45] [a] По политическим причинам Испания иногда утверждала, что Ла-Флорида [b] — это весь североамериканский континент. Однако это название обычно использовалось для обозначения самого полуострова, а также побережья Мексиканского залива , Джорджии, Каролины и южной Вирджинии . [47] В 1521 году Понсе де Леон был убит при попытке основать поселение недалеко от того места, где сейчас находится Шарлотт-Харбор, Флорида . Еще одна неудачная попытка была предпринята Лукасом Васкесом де Айльоном , который отправился примерно с 500 колонистами и основал поселение Сан-Мигель-де-Гуальдапе в современной Южной Каролине в 1526 году. [48]

В 1559 году Тристан де Луна и Арельяно основал первое многолетнее европейское поселение в Соединенных Штатах в том месте, где сейчас находится Пенсакола , Флорида. Это поселение предшествовало основанию Сент-Огастина на шесть лет, отмечая важный, но часто упускаемый из виду момент в истории испанской колонизации. Археологические свидетельства из Университета Западной Флориды подтвердили присутствие экспедиции Луны, которая включала 1500 человек и длилась с 1559 по 1561 год. Артефакты, обнаруженные на месте, обеспечивают прямую связь с ранними попытками Испании колонизировать северное побережье залива. [49]

Осенью 1528 года испанский исследователь Альвар Нуньес Кабеса де Вака высадился на острове Фоллет, штат Техас . [50] В 1565 году Испания основала поселение в Сент-Огастине, штат Флорида , которое просуществовало в той или иной форме до наших дней. Постоянные испанские поселения были основаны в Нью-Мексико , начиная с 1598 года, а Санта-Фе был основан в 1610 году.

Впечатляющие завоевания центральной Мексики (1519–1521) и Перу (1532) разожгли надежды испанцев на поиск еще одной высокой цивилизации. Экспедиции продолжались в 1540-х годах, а региональные столицы были основаны в 1550-х годах. Среди наиболее заметных экспедиций — Эрнандо де Сото на юго-восток Северной Америки, отправившийся из Кубы (1539–1542); Франсиско Васкес де Коронадо в северную Мексику (1540–1542) и Гонсало Писарро в Амазонию, отправившийся из Кито, Эквадор (1541–1542). [51] В 1561 году Педро де Урсуа возглавил экспедицию из примерно 370 испанцев (включая женщин и детей) в Амазонию, чтобы найти Эльдорадо. Гораздо более известным сейчас является Лопе де Агирре , который возглавил мятеж против Урсуа, который был убит. Агирре впоследствии написал письмо Филиппу II, в котором горько жаловался на обращение с завоевателями, такими как он сам, после утверждения контроля короны над Перу. [52] Более ранняя экспедиция, которая отправилась в 1527 году, возглавлялась Панфило Наваесом , который был убит в самом начале. Выжившие продолжали путешествовать среди коренных народов на юге и юго-западе Северной Америки до 1536 года. Альвар Нуньес Кабеса де Вака был одним из четырех выживших в этой экспедиции, написавших отчет о ней. [53] Позже корона отправила его в Асунсьон , Парагвай, чтобы стать там аделантадо . Экспедиции продолжали исследовать территории в надежде найти еще одну империю ацтеков или инков, но безуспешно. Франсиско де Ибарра возглавил экспедицию из Сакатекаса на севере Новой Испании и основал Дуранго . [54] Хуан де Оньяте , которого иногда называют «Последним конкистадором », [55] расширил испанский суверенитет над тем, что сейчас является Нью-Мексико. [56] Как и предыдущие конкистадоры, Оньяте участвовал в широкомасштабных злоупотреблениях в отношении индейского населения. [c] Вскоре после основания Санта-Фе , Оньяте был отозван в Мехико испанскими властями. Впоследствии он был судим и признан виновным в жестоком обращении как с туземцами, так и с колонистами и изгнан из Нью-Мексико на всю жизнь. [57]

Два основных фактора влияли на плотность испанских поселений в долгосрочной перспективе. Одним из них было наличие или отсутствие плотного, иерархически организованного коренного населения, которое можно было заставить работать. Другим было наличие или отсутствие эксплуатируемого ресурса для обогащения поселенцев. Лучшим было золото, но серебро было найдено в изобилии.

Двумя основными областями испанского поселения после 1550 года были Мексика и Перу, места коренных цивилизаций ацтеков и инков, и богатые месторождения ценного металла серебра. Испанское поселение в Мексике «во многом копировало организацию области во времена до завоевания». Однако в Перу центр инков находился слишком далеко на юге, слишком удаленно и на слишком большой высоте для испанской столицы, поэтому столица Лима была построена недалеко от побережья Тихого океана. [58] Столицы Мексики и Перу (Мехико и Лима) стали местом большой концентрации испанских поселенцев и центрами королевской и церковной администрации, крупными коммерческими предприятиями с квалифицированными ремесленниками и центрами культуры. Хотя испанцы надеялись найти огромные количества золота, открытие больших количеств серебра стало двигателем испанской колониальной экономики, основным источником дохода для испанской короны и преобразило международную экономику. Горнодобывающие регионы в Мексике были отдаленными, за пределами зоны коренных поселений в центральной и южной Мексике Месоамерика , но шахты в Сакатекасе (основан в 1548 году) и Гуанахуато (основан в 1548 году) стали ключевыми центрами колониальной экономики. В Перу серебро было найдено в единственной серебряной горе, Серро-Рико-де-Потоси , которая все еще производит серебро в 21 веке. Потоси (основан в 1545 году) находился в зоне плотного проживания коренных народов, поэтому рабочую силу можно было мобилизовать по традиционным схемам для добычи руды. Важным элементом для продуктивной добычи была ртуть для переработки высококачественной руды. У Перу был источник в Уанкавелике (основан в 1572 году), в то время как Мексике приходилось полагаться на ртуть, импортируемую из Испании.

Испанцы основали города на Карибах, на Эспаньоле и Кубе, по образцу, который стал пространственно схожим по всей Испанской Америке. Центральная площадь имела самые важные здания по четырем сторонам, особенно здания для королевских чиновников и главную церковь. Шахматный узор расходился наружу. Резиденции чиновников и элиты были ближе всего к главной площади. Оказавшись на материке, где в городских поселениях было густонаселенное коренное население, испанцы могли построить испанское поселение на том же месте, датируя его основание временем, когда это произошло. Часто они возводили церковь на месте коренного храма. Они воспроизводили существующую коренную сеть поселений, но добавляли портовый город. Испанской сети нужен был портовый город, чтобы внутренние поселения могли быть связаны морем с Испанией. В Мексике Эрнан Кортес и люди его экспедиции основали портовый город Веракрус в 1519 году и провозгласили себя городскими советниками, чтобы сбросить власть губернатора Кубы, который не санкционировал завоевательную экспедицию. После того, как империя ацтеков была свергнута, они основали Мехико на руинах столицы ацтеков. Их центральная официальная и церемониальная зона была построена на вершине ацтекских дворцов и храмов. В Перу испанцы основали город Лиму в качестве своей столицы и близлежащий порт Кальяо , а не высокогорное место Куско , центр правления инков. Испанцы основали сеть поселений в районах, которые они завоевали и контролировали. Среди них можно назвать Сантьяго-де-Гватемала (1524); Пуэбла (1531); Керетаро (ок. 1531); Гвадалахара (1531–42); Вальядолид (ныне Морелия ), (1529–41); Антекера (ныне Оахака (1525–29); Кампече (1541); и Мерида . На юге Центральной и Южной Америки поселения были основаны в Панаме (1519); Леон, Никарагуа (1524); Картахена (1532); Пиура (1532); Кито (1534); Трухильо (1535); Кали (1537) , Богота (1538); Кито ( 1534 г.); Куско 1534 г.); Лима (1535 г.); Тунджа (1539 г.); Уаманга (1539 г.); Арекипа (1540 г.); Сантьяго-де-Чили (1544 г.) и Консепсьон, Чили (1550 г.). С юга были заселены Буэнос-Айрес (1536, 1580); Асунсьон(1537 г.); Потоси (1545 г.); Ла-Пас, Боливия (1548 г.); и Тукуман (1553 г.). [59]

Колумбийский обмен был столь же значительным, как и столкновение цивилизаций. [60] [61] Вероятно, наиболее значительным введением были болезни, принесенные в Америку, которые опустошили коренное население серией эпидемий. Потеря коренного населения оказала прямое влияние и на испанцев, поскольку они все больше видели в этом населении источник своего собственного богатства, исчезающий у них на глазах. [62]

В первых поселениях на Карибах испанцы намеренно привозили животных и растения, которые преобразили экологический ландшафт. Свиньи, крупный рогатый скот, овцы, козы и куры позволяли испанцам питаться привычной для них пищей. Но импорт лошадей изменил военные действия как для испанцев, так и для коренных народов. Хотя испанцы имели эксклюзивный доступ к лошадям в военных действиях, у них было преимущество перед пешими воинами коренных народов. Изначально они были дефицитным товаром, но коневодство стало активной отраслью. Лошади, которые избегали испанского контроля, были захвачены коренными народами; многие коренные народы также совершали набеги ради лошадей. Конные воины коренных народов были серьезными противниками для испанцев. Чичимеки на севере Мексики, команчи на севере Великих равнин и мапуче на юге Чили и в пампасах Аргентины сопротивлялись испанскому завоеванию. Для испанцев свирепые чичимеки преградили им путь к эксплуатации горнодобывающих ресурсов на севере Мексики. Испанцы вели пятидесятилетнюю войну (ок. 1550–1600 гг.), чтобы покорить их, но мир был достигнут только благодаря значительным пожертвованиям испанцами продовольствия и других товаров, которые требовали чичимеки. «Мир покупкой» положил конец конфликту. [63] На юге Чили и в пампасах арауканы (мапуче) предотвратили дальнейшую испанскую экспансию. Образ конных арауканов, захватывающих и увозящих белых женщин, был воплощением испанских идей цивилизации и варварства.

Крупный рогатый скот быстро размножался в районах, где мало что еще могло принести прибыль испанцам, включая северную Мексику и аргентинские пампасы. Введение производства овец стало экологической катастрофой в местах, где их выращивали в больших количествах, поскольку они съедали растительность до основания, препятствуя регенерации растений. [64]

The Spanish brought new crops for cultivation. (See Mission Garden for specific foods.) They preferred wheat cultivation to indigenous sources of carbohydrates: casava, maize (corn), and potatoes, initially importing seeds from Europe and planting in areas where plow agriculture could be utilized, such as the Mexican Bajío. They also imported cane sugar, which was a high-value crop in early Spanish America. Spaniards also imported citrus trees, establishing orchards of oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruit. Other imports were figs, apricots, cherries, pears, and peaches among others. The exchange did not go one way. Important indigenous crops that transformed Europe were the potato and maize, which produced abundant crops that led to the expansion of populations in Europe. Chocolate and vanilla were cultivated in Mexico and exported to Europe. Among the foodstuffs that became staples in European cuisine and could be grown there were tomatoes, squashes, bell peppers, cashews, pecans and peanuts.[citation needed]

The empire in the Indies was a newly established dependency of the kingdom of Castile alone, so crown power was not impeded by any existing cortes (i.e. parliament), administrative or ecclesiastical institution, or seigneurial group.[65] The crown sought to establish and maintain control over its overseas possessions through a complex, hierarchical bureaucracy, which in many ways was decentralized. The crown asserted is authority and sovereignty of the territory and vassals it claimed, collected taxes, maintained public order, meted out justice, and established policies for governance of large indigenous populations. Many institutions established in Castile found expression in The Indies from the early colonial period. Spanish universities expanded to train lawyer-bureaucrats (letrados) for administrative positions in Spain and its overseas empire.

The end of the Habsburg dynasty in 1700 saw major administrative reforms in the eighteenth century under the Bourbon monarchy, starting with the first Spanish Bourbon monarch, Philip V (r. 1700–1746) and reaching its apogee under Charles III (r. 1759–1788). The reorganization of administration has been called "a revolution in government."[66] Reforms sought to centralize government control through reorganization of administration, reinvigorate the economies of Spain and the Spanish empire through changes in mercantile and fiscal policies, defend Spanish colonies and territorial claims through the establishment of a standing military, undermine the power of the Catholic church, and rein in the power of the American-born elites.[67]

The crown relied on ecclesiastics as important councilors and royal officials in the governance of their overseas territories. Archbishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, Isabella's confessor, was tasked with reining in Columbus's independence. He strongly influenced the formulation of colonial policy under the Catholic Monarchs, and was instrumental in establishing the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) (1503), which enabled crown control over trade and immigration. Ovando fitted out Magellan's voyage of circumnavigation, and became the first President of the Council of the Indies in 1524.[68] Ecclesiastics also functioned as administrators overseas in the early Caribbean period, particularly Frey Nicolás de Ovando, who was sent to investigate the administration of Francisco de Bobadilla, the governor appointed to succeed Christopher Columbus.[69] Later ecclesiastics served as interim viceroys, general inspectors (visitadores), and other high posts.

The crown established control over trade and emigration to the Indies with the 1503 establishment the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) in Seville. Ships and cargoes were registered, and emigrants vetted to prevent migration of anyone not of Old Christian heritage, (i.e., with no Jewish or Muslim ancestry), and facilitated the migration of families and women.[70] In addition, the Casa de Contratación took charge of the fiscal organization, and of the organization and judicial control of the trade with the Indies.[71]

The politics of asserting royal authority to oppose Columbus resulted in the suppression of his privileges and the creation of territorial governance under royal authority. These governorates, also called as provinces, were the basic of the territorial government of the Indies,[72] and arose as the territories were conquered and colonized.[73] To carry out the expedition (entrada), which entailed exploration, conquest, and initial settlement of the territory, the king, as sovereign, and the appointed leader of an expedition (adelantado) agreed to an itemized contract (capitulación), with the specifics of the conditions of the expedition in a particular territory. The individual leaders of expeditions assumed the expenses of the venture and in return received as reward the grant from the government of the conquered territories;[74] and in addition, they received instructions about treating the indigenous peoples.[75]

After the end of the period of conquests, it was necessary to manage extensive and different territories with a strong bureaucracy. In the face of the impossibility of the Castilian institutions to take care of the New World affairs, other new institutions were created.[76]

As the basic political entity it was the governorate, or province. The governors exercised judicial ordinary functions of first instance, and prerogatives of government legislating by ordinances.[77] To these political functions of the governor, it could be joined the military ones, according to military requirements, with the rank of Captain general.[78] The office of captain general involved to be the supreme military chief of the whole territory and he was responsible for recruiting and providing troops, the fortification of the territory, the supply and the shipbuilding.[79]

Beginning in 1522 in the newly conquered Mexico, government units in the Spanish empire had a royal treasury controlled by a set of oficiales reales (royal officials). There were also sub-treasuries at important ports and mining districts. The officials of the royal treasury at each level of government typically included two to four positions: a tesorero (treasurer), the senior official who guarded money on hand and made payments; a contador (accountant or comptroller), who recorded income and payments, maintained records, and interpreted royal instructions; a factor, who guarded weapons and supplies belonging to the king, and disposed of tribute collected in the province; and a veedor (overseer), who was responsible for contacts with native inhabitants of the province, and collected the king's share of any war booty. The veedor, or overseer, position quickly disappeared in most jurisdictions, subsumed into the position of factor. Depending on the conditions in a jurisdiction, the position of factor/veedor was often eliminated, as well.[80]

The treasury officials were appointed by the king, and were largely independent of the authority of the viceroy, audiencia president or governor. On the death, unauthorized absence, retirement or removal of a governor, the treasury officials would jointly govern the province until a new governor appointed by the king could take up his duties. Treasury officials were supposed to be paid out of the income from the province, and were normally prohibited from engaging in income-producing activities.[81]

The protection of the indigenous populations from enslavement and exploitation by Spanish settlers were established in the Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513. The laws were the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of Spanish settlers in the Americas, particularly with regards to treatment of native Indians in the institution of the encomienda. They forbade the maltreatment of natives, and endorsed the forced resettlement of indigenous populations with attempts of conversion to Catholicism.[82] Upon their failure to effectively protect the indigenous and following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and the Spanish conquest of Peru, more stringent laws to control conquerors' and settlers' exercise of power, especially their maltreatment of the indigenous populations, were promulgated, known as the New Laws (1542). The crown aimed to prevent the formation of an aristocracy in the Indies not under crown control.

Queen Isabel was the first monarch that laid the first stone for the protection of the indigenous peoples in her testament in which the Catholic monarch prohibited the enslavement of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.[83] Then the first such in 1542; the legal thought behind them was the basis of modern International law.[84]

The Valladolid debate (1550–1551) was the first moral debate in European history to discuss the rights and treatment of a colonized people by colonizers. Held in the Colegio de San Gregorio, in the Spanish city of Valladolid, it was a moral and theological debate about the colonization of the Americas, its justification for the conversion to Catholicism and more specifically about the relations between the European settlers and the natives of the New World. It consisted of a number of opposing views about the way natives were to be integrated into colonial life, their conversion to Christianity and their rights and obligations. According to the French historian Jean Dumont The Valladolid debate was a major turning point in world history "In that moment in Spain appeared the dawn of the human rights".[85]

The indigenous populations in the Caribbean became the focus of the crown in its roles as sovereigns of the empire and patron of the Catholic Church. Spanish conquerors holding grants of indigenous labor in encomienda ruthlessly exploited them. A number of friars in the early period came to the vigorous defense of the indigenous populations, who were new converts to Christianity. Prominent Dominican friars in Santo Domingo, especially Antonio de Montesinos and Bartolomé de las Casas denounced the maltreatment and pressed the crown to act to protect the indigenous populations. The crown enacted Laws of Burgos (1513) and the Requerimiento to curb the power of the Spanish conquerors and give indigenous populations the opportunity to peacefully embrace Spanish authority and Christianity. Neither was effective in its purpose. Las Casas was officially appointed Protector of the Indians and spent his life arguing forcefully on their behalf. The New Laws of 1542 were the result, limiting the power of encomenderos, the private holders of grants to indigenous labor previously held in perpetuity. The crown was open to limiting the inheritance of encomiendas in perpetuity as a way to extinguish the coalescence of a group of Spaniards impinging on royal power. In Peru, the attempt of the newly appointed viceroy, Blasco Núñez Vela, to implement the New Laws so soon after the conquest sparked a revolt by conquerors against the viceroy and the viceroy was killed in 1546.[86] In Mexico, Don Martín Cortés, the son and legal heir of conqueror Hernán Cortés, and other heirs of encomiendas led a failed revolt against the crown. Don Martín was sent into exile, while other conspirators were executed.[87]

The conquest of the Aztec and Inca empires ended their sovereignty over their respective territorial expanses, replaced by the Spanish Empire, and indigenous religious beliefs and practices were suppressed and populations converted to Christianity. The Spanish Empire could not have ruled these vast territories and dense indigenous populations without utilizing the existing indigenous political and economic structures at the local level. A key to this was the cooperation between most indigenous elites with the new ruling structure. The Spanish recognized indigenous elites as nobles and gave them continuing standing in their communities. Indigenous elites could use the noble titles don and doña, were exempt from the head-tax, and could entail their landholdings into cacicazgos.[88] These elites played an intermediary role between the Spanish rulers and indigenous commoners. Since in Mesoamerica and the Andean civilizations, indigenous peoples had existing traditions of payment of tribute and required labor service, the Spanish could tap into these systems to extract wealth. There were few Spaniards and huge indigenous populations, so utilizing indigenous intermediaries was a practical solution to the incorporation of the indigenous population into the new regime of rule. By maintaining hierarchical divisions within communities, indigenous noblemen were the direct interface between the indigenous and Spanish spheres and kept their positions so long as they continued to be loyal to the Spanish crown.[89][90][91][92][93]

The exploitation and demographic catastrophe that indigenous peoples experienced from Spanish rule in the Caribbean also occurred as Spaniards expanded their control over territories and their indigenous populations. The crown set the indigenous communities legally apart from Spaniards (as well as Blacks), who made up the República de Españoles, with the creation of the República de Indios. The crown attempted to curb Spaniards' exploitation, banning Spaniards' bequeathing their private grants of indigenous communities' tribute and encomienda labor in 1542 in the New Laws.[94] In Mexico, the crown established the General Indian Court (Juzgado General de Indios), which heard disputes affecting individual indigenous as well as indigenous communities. Lawyers for these cases were funded by a half-real tax, an early example of legal aid for the poor.[95] A similar legal apparatus was set up in Lima.[96]

.jpg/440px-Ayuntamiento_de_Tlaxcala_-_panoramio_(1).jpg)

The Spaniards systematically attempted to transform structures of indigenous governance to those more closely resembling those of Spaniards, so the indigenous city-state became a Spanish town and the indigenous noblemen who ruled became officeholders of the town council (cabildo). Although the structure of the indigenous cabildo looked similar to that of the Spanish institution, its indigenous functionaries continued to follow indigenous practices. In central Mexico, there exist minutes of the sixteenth-century meetings in Nahuatl of the Tlaxcala cabildo.[97] Indigenous noblemen were particularly important in the early period of colonization, since the economy of the encomienda was initially built on the extraction of tribute and labor from the commoners in their communities. As the colonial economy became more diversified and less dependent on these mechanisms for the accumulation of wealth, the indigenous noblemen became less important for the economy. However, noblemen became defenders of the rights to land and water controlled by their communities. In colonial Mexico, there are petitions to the king about a variety of issues important to particular indigenous communities when the noblemen did not get a favorable response from the local friar or priest or local royal officials.

Works by historians in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have expanded the understanding of the impact of the Spanish conquest and changes during the more than three hundred years of Spanish rule. There are many such works for Mexico, often drawing on native-language documentation in Nahuatl,[98][99] Mixtec,[100] and Yucatec Maya.[101][102] For the Andean area, there are an increasing number of publications as well.[103][104] The history of the Guaraní has also been the subject of a recent study.[105]

In 2000, Pope John Paul II apologized for the wrongs done by the Catholic Church, including those to indigenous peoples.[106] In 2007 Pope Benedict XVI issued a less sweeping apology for the wrongs done in the conversion of indigenous peoples.[107]

In 1524 the Council of the Indies was established, following the system of system of Councils that advised the monarch and made decisions on his behalf about specific matters of government.[108] Based in Castile, with the assignment of the governance of the Indies, it was thus responsible for drafting legislation, proposing the appointments to the King for civil government as well as ecclesiastical appointments, and pronouncing judicial sentences; as maximum authority in the overseas territories, the Council of the Indies took over both the institutions in the Indies as the defense of the interests of the Crown, the Catholic Church, and of indigenous peoples.[109] With the 1508 papal grant to the crown of the Patronato real, the crown, rather than the pope, exercised absolute power over the Catholic Church in the Americas and the Philippines, a privilege the crown zealously guarded against erosion or incursion. Crown approval through the Council of the Indies was needed for the establishment of bishoprics, building of churches, appointment of all clerics.[110]

In 1721, at the beginning of the Bourbon monarchy, the crown transferred the main responsibility for governing the overseas empire from the Council of the Indies to the Ministry of the Navy and the Indies, which were subsequently divided into two separate ministries in 1754.[67]

The impossibility of the physical presence of the monarch and the necessity of strong royal governance in The Indies resulted in the appointment of viceroys ("vice-kings"), the direct representation of the monarch, in both civil and ecclesiastical spheres. Viceroyalties were the largest territory unit of administration in the civil and religious spheres and the boundaries of civil and ecclesiastical governance coincided by design, to ensure crown control over both bureaucracies.[111] Until the eighteenth century, there were just two viceroyalties, with the Viceroyalty of New Spain (founded 1535) administering North America, a portion of the Caribbean, and the Philippines, and the viceroyalty of Peru (founded 1542) having jurisdiction over Spanish South America. Viceroys served as the vice-patron of the Catholic Church, including the Inquisition, established in the seats of the viceroyalties (Mexico City and Lima). Viceroys were responsible for good governance of their territories, economic development, and humane treatment of the indigenous populations.[112]

In the eighteenth-century reforms, the Viceroyalty of Peru was reorganized, splitting off portions to form the Viceroyalty of New Granada (Colombia) (1739) and the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata (Argentina) (1776), leaving Peru with jurisdiction over Peru, Charcas, and Chile. Viceroys were of high social standing, almost without exception born in Spain, and served fixed terms.

The Audiencias were initially constituted by the crown as a key administrative institution with royal authority and loyalty to the crown as opposed to conquerors and first settlers.[113] Although constituted as the highest judicial authority in their territorial jurisdiction, they also had executive and legislative authority, and served as the executive on an interim basis. Judges (oidores) held "formidable power. Their role in judicial affairs and in overseeing the implementation of royal legislation made their decisions important for the communities they served." Since their appointments were for life or the pleasure of the monarch, they had a continuity of power and authority that viceroys and captains-general lacked because of their shorter-term appointments.[114] They were the "center of the administrative system [and] gave the government of the Indies a strong basis of permanence and continuity."[115]

Their main function was judicial, as a court of justice of second instance – court of appeal – in penal and civil matters, but also the Audiencias were courts the first instance in the city where it had its headquarters, and also in the cases involving the Royal Treasury.[116] Besides court of justice, the Audiencias had functions of government as counterweight the authority of the viceroys, since they could communicate with both the Council of the Indies and the king without the requirement of requesting authorization from the viceroy.[116] This direct correspondence of the Audiencia with the Council of the Indies made it possible for the council to give the Audiencia direction on general aspects of government.[113]

Audiencias were a significant base of power and influence for American-born elites, starting in the late sixteenth century, with nearly a quarter of appointees being born in the Indies by 1687. During a financial crisis in the late seventeenth century, the crown began selling Audiencia appointments, and American-born Spaniards held 45% of Audiencia appointments. Although there were restrictions of appointees' ties to local elite society and participation in the local economy, they acquired dispensations from the cash-strapped crown. Audiencia judgments and other functions became more tied to the locality and less to the crown and impartial justice.

During the Bourbon Reforms in the mid-eighteenth century, the crown systematically sought to centralize power in its own hands and diminish that of its overseas possessions, appointing peninsular-born Spaniards to Audiencias. American-born elite men complained bitterly about the change, since they lost access to power that they had enjoyed for nearly a century.[114]

During the early era and under the Habsburgs, the crown established a regional layer of colonial jurisdiction in the institution of Corregimiento, which was between the Audiencia and town councils. Corregimiento expanded "royal authority from the urban centers into the countryside and over the indigenous population."[117] As with many colonial institutions, corregimiento had its roots in Castile when the Catholic Monarchs centralize power over municipalities. In the Indies, corregimiento initially functioned to bring control over Spanish settlers who exploited the indigenous populations held in encomienda, in order to protect the shrinking indigenous populations and prevent the formation of an aristocracy of conquerors and powerful settlers. The royal official in charge of a district was the Corregidor, who was appointed by the viceroy, usually for a five-year term. Corregidores collected the tribute from indigenous communities and regulated forced indigenous labor. Alcaldías mayores were larger districts with a royal appointee, the Alcalde mayor.

As the indigenous populations declined, the need for corregimiento decreased and then suppressed, with the alcaldía mayor remaining an institution until it was replaced in the eighteenth-century Bourbon Reforms by royal officials, Intendants. The salary of officials during the Habsburg era were paltry, but the corregidor or alcalde mayor in densely populated areas of indigenous settlement with a valuable product could use his office for personal enrichment. As with many other royal posts, these positions were sold, starting in 1677.[117] The Bourbon-era intendants were appointed and relatively well paid.[118]

Spanish settlers sought to live in towns and cities, with governance being accomplished through the town council or Cabildo. The cabildo was composed of the prominent residents (vecinos) of the municipality, so that governance was restricted to a male elite, with majority of the population exercising power. Cities were governed on the same pattern as in Spain and in the Indies the city was the framework of Spanish life. The cities were Spanish and the countryside indigenous.[119] In areas of previous indigenous empires with settled populations, the crown also melded existing indigenous rule into a Spanish pattern, with the establishment of cabildos and the participation of indigenous elites as officials holding Spanish titles. There were a variable number of councilors (regidores), depending on the size of the town, also two municipal judges (alcaldes menores), who were judges of first instance, and also other officials as police chief, inspector of supplies, court clerk, and a public herald.[120] They were in charge of distributing land to the neighbors, establishing local taxes, dealing with the public order, inspecting jails and hospitals, preserving the roads and public works such as irrigation ditches and bridges, supervising public health, regulating festive activities, monitoring market prices, or the protection of Indians.[121]

After the reign of Philip II, the municipal offices, including the councilors, were auctioned to alleviate the need for money of the Crown, even the offices could also be sold, which became hereditary,[122] so that the government of the cities went on to hands of urban oligarchies.[123] In order to control the municipal life, the Crown ordered the appointment of corregidores and alcaldes mayores to exert greater political control and judicial functions in minor districts.[124] Their functions were governing the respective municipalities, administering of justice and being appellate judges in the alcaldes menores' judgments,[125] but only the corregidor could preside over the cabildo.[126] However, both charges were also put up for sale freely since the late 16th century.[127]

Most Spanish settlers came to the Indies as permanent residents, established families and businesses, and sought advancement in the colonial system, such as membership of cabildos, so that they were in the hands of local, American-born (crillo) elites. During the Bourbon era, even when the crown systematically appointed peninsular-born Spaniards to royal posts rather than American-born, the cabildos remained in the hands of local elites.[128]

As the empire expanded into areas of less dense indigenous populations, the crown created a chain of presidios, military forts or garrisons, that provided Spanish settlers protection from Indian attacks. In Mexico during the sixteenth-century Chichimec War guarded the transit of silver from the mines of Zacatecas to Mexico City. As many as 60 salaried soldiers were garrisoned in presidios.[129] Presidios had a resident commanders, who set up commercial enterprises of imported merchandise, selling it to soldiers as well as Indian allies.[130]

The other frontier institution was the religious mission to convert the indigenous populations. Missions were established with royal authority through the Patronato real. The Jesuits were effective missionaries in frontier areas until their expulsion from Spain and its empire in 1767. The Franciscans took over some former Jesuit missions and continued the expansion of areas incorporated into the empire. Although their primary focus was on religious conversion, missionaries served as "diplomatic agents, peace emissaries to hostile tribes ... and they were also expected to hold the line against nomadic nonmissionary Indians as well as other European powers."[131] On the frontier of empire, Indians were seen as sin razón, ("without reason"); non-Indian populations were described as gente de razón ("people of reason"), who could be mixed-race castas or black and had greater social mobility in frontier regions.[132]

Christian evangelization of non-Christian peoples was a key factor in Spaniards' justification of the conquest of indigenous peoples in what was called "the spiritual conquest". In 2000, Pope John Paul II apologized for errors committed by the Catholic Church, including forced conversion.[106]

During the early colonial period, the crown authorized friars of Catholic religious orders (Franciscans, Dominicans, and Augustinians) to function as priests during the conversion of indigenous populations. During the early Age of Discovery, the diocesan clergy in Spain was poorly educated and considered of a low moral standing, and the Catholic Monarchs were reluctant to allow them to spearhead evangelization. Each order set up networks of parishes in the various regions (provinces), sited in existing indigenous settlements, where Christian churches were built and where evangelization of the indigenous was based. Hernán Cortés requested Franciscan and Dominican friars be sent to New Spain immediately after the conquest of Tenochtitlan to begin evangelization. The Franciscans arrived first in 1525 in a group of twelve, the Twelve Apostles of Mexico. Among this first group was Toribio de Benavente, known now as Motolinia, the Nahuatl word for poor.[133][134]

After the 1550s, the crown increasingly favored the diocesan clergy over the religious orders. The diocesan clergy (also called the secular clergy) were under the direct authority of bishops, who were appointed by the crown, through the power granted by the pope in the Patronato real. Religious orders had their own internal regulations and leadership. The crown had authority to draw the boundaries for dioceses and parishes. The creation of the ecclesiastical hierarchy of the diocesan clergy marked a turning point in the crown's control over the religious sphere. The structure of the hierarchy was in many ways parallel to that of civil governance. The pope was the head of the Catholic Church, but the granting of the Patronato real to the Spanish monarchy gave the king the power of appointment (patronage) of ecclesiastics. The monarch was head of the civil and religious hierarchies. The capital city of a viceroyalty became of the seat of the archbishop. The region overseen by the archbishop was divided into large units, the diocese, headed by a bishop. The diocese was in turn divided into smaller units, the parish, staffed by a parish priest.

In 1574, Philip II promulgated the Order of Patronage (Ordenaza del Patronato) ordering the religious orders to turn over their parishes to the secular clergy, a policy that secular clerics had long sought for the central areas of empire, with their large indigenous populations. Although implementation was slow and incomplete, it was an assertion of royal power over the clergy and the quality of parish priests improved, since the Ordenanza mandated competitive examination to fill vacant positions.[135][136] Religious orders along with the Jesuits then embarked on further evangelization in frontier regions of the empire.

The Jesuits resisted crown control, refusing to pay the tithe on their estates that supported the ecclesiastical hierarchy and came into conflict with bishops. The most prominent example is in Puebla, Mexico, when Bishop Juan de Palafox y Mendoza was driven from his bishopric by the Jesuits. The bishop challenged the Jesuits' continuing to hold Indian parishes and function as priests without the required royal licenses. His fall from power is viewed as an example of the weakening of the crown in the mid-seventeenth century since it failed to protect their duly appointed bishop.[137] The crown expelled the Jesuits from Spain and The Indies in 1767 during the Bourbon Reforms.

Inquisitional powers were initially vested in bishops, who could root out idolatry and heresy. In Mexico, Bishop Juan de Zumárraga prosecuted and had executed in 1539 a Nahua lord, known as Don Carlos of Texcoco for apostasy and sedition for having converted to Christianity and then renounced his conversion and urged others to do so as well. Zumárraga was reprimanded for his actions as exceeding his authority.[138][139] When the formal institution of the Inquisition was established in 1571, indigenous peoples were excluded from its jurisdiction on the grounds that they were neophytes, new converts, and not capable of understanding religious doctrine.

It has been estimated that over 1.86 million Spaniards emigrated to Latin America in the period between 1492 and 1824, with millions more continuing to immigrate following independence.[140]

Native populations declined significantly during the period of Spanish expansion. In Hispaniola, the indigenous Taíno pre-contact population before the arrival of Columbus of several hundred thousand had declined to sixty thousand by 1509. The population of the Native American population in Mexico declined by an estimated 90% (reduced to 1–2.5 million people) by the early 17th century.[citation needed] In Peru, the indigenous Amerindian pre-contact population of around 6.5 million declined to 1 million by the early 17th century.[citation needed] The overwhelming cause of the decline in both Mexico and Peru was infectious diseases, such as smallpox and measles,[141] although the brutality of the encomienda also played a significant part in the population decline.[citation needed]

Of the history of the indigenous population of California, Sherburne F. Cook (1896–1974) was the most painstakingly careful researcher. From decades of research, he made estimates for the pre-contact population and the history of demographic decline during the Spanish and post-Spanish periods. According to Cook, the indigenous Californian population at first contact, in 1769, was about 310,000 and had dropped to 25,000 by 1910. The vast majority of the decline happened after the Spanish period, during the Mexican and US periods of Californian history (1821–1910), with the most dramatic collapse (200,000 to 25,000) occurring in the US period (1846–1910).[142][143][144]

The largest population in Spanish America was and remained indigenous, what Spaniards called "Indians" (indios), a category that did not exist before the arrival of the Europeans. The Spanish Crown separated them into the República de Indios. Europeans immigrated from various provinces of Spain, with initial waves of emigration consisting of more men than women. They were referred to as Españoles and Españolas, and later being differentiated by the terms indicating place of birth, peninsular for those born in Spain; criollo/criolla or Americano/Ameriana for those born in the Americas. Enslaved Africans were imported to Spanish territories, primarily to Cuba. As was the case in peninsular Spain, Africans (negros) were able buy their freedom (horro), so that in most of the empire free Blacks and Mulatto (Black + Spanish) populations outnumbered slave populations. Spaniards and Indigenous parents produced Mestizo offspring, who were also part of the República de Españoles.[citation needed]

In areas of dense, stratified indigenous populations, especially Mesoamerica and the Andean region, Spanish conquerors awarded perpetual private grants of labor and tribute to particular indigenous settlements, in encomienda they were in a privileged position to accumulate private wealth. Spaniards had some knowledge of the existing indigenous practices of labor and tribute, so that learning in more detail what tribute particular regions delivered to the Aztec Empire prompted the creation of Codex Mendoza, a codification for Spanish use. The rural regions remained highly indigenous, with little interface between the large numbers of indigenous and the small numbers of the República de Españoles, which included Blacks and mixed-race castas. Tribute goods in Mexico were most usually lengths of cotton cloth, woven by women, and maize and other foodstuffs produced by men. These could be sold in markets and thereby converted to cash. In the early period for Spaniards, formal ownership of land was less important than control of indigenous labor and receiving tribute. Spaniards had seen the disappearance of the indigenous populations in the Caribbean, and with that, the disappearance of their main source of wealth, propelling Spaniards to expand their regions of control. With the conquests of the Aztec and Inca empires, large numbers of Spaniards emigrated from the Iberian peninsula to seek their fortune or to pursue better economic conditions for themselves. The establishment of large, permanent Spanish settlements attracted a whole range of new residents, who set up shop as carpenters, bakers, tailors and other artisan activities.

The early Caribbean proved a massive disappointment for Spaniards, who had hoped to find mineral wealth and exploitable indigenous populations. Gold existed in only small amounts, and the indigenous peoples died off in massive numbers. For the colony's continued existence, a reliable source of labor was needed. That was of enslaved Africans. Cane sugar imported from the Old World was a high value, a low bulk export product that became the bulwark of tropical economies of the Caribbean islands and coastal Tierra Firme (the Spanish Main), as well as Portuguese Brazil.

Silver was the bonanza the Spaniards sought. Large deposits were found in a single mountain in the viceroyalty of Peru, the Cerro Rico, in what is now Bolivia, and in several places outside of the dense indigenous zone of settlement in northern Mexico, Zacatecas and Guanajuato.[145] In the Andes, Viceroy Francisco de Toledo revived the indigenous rotary labor system of the mita to supply labor for silver mining.[146][147][148] In Mexico, the labor force had to be lured from elsewhere in the colony, and was not based on traditional systems of rotary labor. In Mexico, refining took place in haciendas de minas, where silver ore was refined into pure silver by amalgamation with mercury in what was known as the patio process. Ore was crushed with the aid of mules and then mercury could be applied to draw out the pure silver. Mercury was a monopoly of the crown. In Peru, the Cerro Rico's ore was processed from the local mercury mine of Huancavelica, while in Mexico mercury was imported from the Almadén mercury mine in Spain. Mercury is a neurotoxin, which damaged and killed human and mules coming into contact with it. In the Huancavelica region, mercury continues to wreak ecological damage.[149][150][151]

To feed urban populations and mining workforces, small-scale farms (ranchos), (estancias), and large-scale enterprises (haciendas) emerged to fill the demand, especially for foodstuffs that Spaniards wanted to eat, most especially wheat. In areas of sparse population, ranching of cattle (ganado mayor) and smaller livestock (ganado menor) such as sheep and goats ranged widely and were largely feral. There is debate about the impact of ranching on the environment in the colonial era, with sheep herding being called out for its negative impact, while others contest that.[152] With only a small labor force to draw on, ranching was an ideal economic activity for some regions. Most agriculture and ranching supplied local needs, since transportation was difficult, slow, and expensive.[153] Only the most valuable low bulk products would be exported.

Cacao beans for chocolate emerged as an export product as Europeans developed a taste for sweetened chocolate. Another important export product was cochineal, a color-fast red dye made from dried insects living on cacti. It became the second-most valuable export from Spanish America after silver.[154]

During the Napoleonic Peninsular War in Europe between France and Spain, assemblies called juntas were established to rule in the name of Ferdinand VII of Spain. The Libertadores (Spanish and Portuguese for "Liberators") were the principal leaders of the Spanish American wars of independence. They were predominantly criollos (Americas-born people of European ancestry, mostly Spanish or Portuguese), bourgeois and influenced by liberalism and in some cases with military training in the mother country.

In 1809 the first declarations of independence from Spanish rule occurred in the Viceroyalty of Peru. The first two were in Upper Peru, present-day Bolivia, at Charcas (present day Sucre, 25 May), and La Paz (16 July); and the third in present-day Ecuador at Quito (10 August). In 1810 Mexico declared independence, with the Mexican War of Independence following for over a decade. In 1821 Treaty of Córdoba established Mexican independence from Spain and concluded the War. The Plan of Iguala was part of the peace treaty to establish a constitutional foundation for an independent Mexico.

These began a movement for colonial independence that spread to Spain's other colonies in the Americas. The ideas from the French and the American Revolution influenced the efforts. All of the colonies, except Cuba and Puerto Rico, attained independence by the 1820s. The British Empire offered support, wanting to end the Spanish monopoly on trade with its colonies in the Americas.

In 1898, the United States achieved victory in the Spanish–American War with Spain, ending the Spanish colonial era. Spanish possession and rule of its remaining colonies in the Americas ended in that year with its sovereignty transferred to the United States. The United States took occupation of Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico continues to be a possession of the United States, now officially continues as a self-governing unincorporated territory.

In the twentieth century, there have been a number of films depicting the life of Christopher Columbus. One in 1949 stars Fredric March as Columbus.[155] With the 1992 commemoration (and critique) of Columbus, more cinematic and television depictions of the era appeared, including a television miniseries with Gabriel Byrne as Columbus.[156] Christopher Columbus: The Discovery (1992) has Georges Corroface as Columbus with Marlon Brando as Tomás de Torquemada and Tom Selleck as King Ferdinand and Rachel Ward as Queen Isabela.[157] 1492: The Conquest of Paradise stars Gérard Depardieu as Columbus and Sigourney Weaver as Queen Isabel.[158] A 2010 film, Even the Rain starring Gael García Bernal, is set in modern Cochabamba, Bolivia during the Cochabamba Water War, following a film crew shooting a controversial life of Columbus.[159][160] A 1995 Bolivian-made film is in some ways similar to Even the Rain is To Hear the Birds Singing, with a modern film crew going to an indigenous settlement to shoot a film about the Spanish conquest and end up replicating aspects of the conquest.[161]

For the conquest of the Aztec Empire, the 2019 eight-episode Mexican television miniseries Hernán depicts such historical events. Other notable historical figures in the production are Malinche, Cortés cultural translator, and other conquerors Pedro de Alvarado, Cristóbal de Olid, Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Showing the indigenous sides are Xicotencatl, a leader of the Spaniards' Tlaxcalan allies, and Aztec emperors Moctezuma II and Cuitláhuac.[162] The story of Doña Marina, also known as Malinche, was the subject of a Mexican television miniseries in 2018.[163] A major production in Mexico was the 1998 film, The Other Conquest, which focuses on a Nahua man in the post-conquest era and the evangelization of central Mexico.[164]

The epic journey of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca has been portrayed in a 1991 feature-length Mexican film, Cabeza de Vaca.[165] The similarly epic and dark journey of Lope de Aguirre was made into a film by Werner Herzog, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), starring Klaus Kinski.[166]

The Mission was a 1996 film idealizing a Jesuit mission to the Guaraní in the territory disputed between Spain and Portugal. The film starred Robert De Niro, Jeremy Irons, and Liam Neeson and It won an Academy Award.[167]

The life of seventeenth-century Mexican nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, renowned in her lifetime, has been portrayed in a 1990 Argentine film, I, the Worst of All[168] and in the television miniseries Juana Inés.[169] Seventeenth-century Mexican trickster Martín Garatuza was the subject of a late nineteenth-century novel by Mexican politician and writer, Vicente Riva Palacio. In the twentieth century, Garatuza's life was the subject of a 1935 film[170] and a 1986 telenovela, Martín Garatuza.[171]

For the independence era, the 2016 Bolivian-made film made about Mestiza independence leader Juana Azurduy de Padilla, Juana Azurduy, Guerrillera de la Patria Grande, is part of the recent recognition of her role in the independence of Argentina and Bolivia.[172]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Sucre State Government: Cumaná in History (Spanish)cabildo.