Армия США ( США ) — сухопутная служба Вооружённых сил США . Это одна из восьми вооружённых сил США , и в Конституции США она обозначена как Армия Соединённых Штатов . [15] Армия является старейшей ветвью вооружённых сил США и самой старшей в порядке старшинства. [16] Она берёт своё начало в Континентальной армии , которая была сформирована 14 июня 1775 года для борьбы с британцами за независимость во время Войны за независимость США (1775–1783). [17] После Войны за независимость Конгресс Конфедерации создал Армию Соединённых Штатов 3 июня 1784 года для замены расформированной Континентальной армии. [18] [19] Армия Соединённых Штатов считает себя продолжением Континентальной армии и, таким образом, считает своё институциональное начало началом этой вооружённой силы в 1775 году. [17]

Армия США является униформой Соединенных Штатов и является частью Министерства армии , которое является одним из трех военных департаментов Министерства обороны . Армию США возглавляет гражданский старший назначенный гражданский служащий, секретарь армии (SECARMY), и главный военный офицер , начальник штаба армии (CSA), который также является членом Объединенного комитета начальников штабов . Это крупнейшая военная ветвь, и в финансовом году 2022 прогнозируемая конечная численность регулярной армии (США) составляла 480 893 солдата; Национальная гвардия армии (ARNG) имела 336 129 солдат, а Резерв армии США (USAR) имел 188 703 солдата; объединенная численность компонентов армии США составляла 1 005 725 солдат. [20] Как род войск, миссия армии США заключается в том, чтобы «воевать и побеждать в войнах нашей страны, обеспечивая быстрое и устойчивое господство на суше во всем диапазоне военных операций и спектре конфликтов, в поддержку боевых командиров ». [21] Род войск участвует в конфликтах по всему миру и является основной наземной наступательной и оборонительной силой Соединенных Штатов Америки.

Армия Соединенных Штатов является сухопутным подразделением Вооруженных сил США . Раздел 7062 Раздела 10 Свода законов США определяет цель армии следующим образом: [22] [23]

В 2018 году в Стратегии армии 2018 года было сформулировано дополнение из восьми пунктов к Видению армии на 2028 год. [24] В то время как Миссия армии остается неизменной, Стратегия армии основывается на Модернизации бригады армии , уделяя особое внимание эшелонам на уровне корпуса и дивизии . [24] Командование будущего армии курирует реформы, направленные на ведение обычных боевых действий . Текущий план реорганизации армии должен быть завершен к 2028 году. [24]

Пять основных компетенций армии — это быстрые и непрерывные наземные бои, общевойсковые операции (включая общевойсковой маневр и широкомасштабную безопасность, бронетанковые и механизированные операции , воздушно -десантные и воздушно - штурмовые операции ), силы специальных операций , создание и поддержание театра военных действий для объединенных сил, а также интеграция национальных, многонациональных и совместных сил на суше. [25]

Континентальная армия была создана 14 июня 1775 года Вторым Континентальным конгрессом [26] как единая армия колоний для борьбы с Великобританией , а Джордж Вашингтон был назначен ее командующим. [17] [27] [28] [29] Первоначально армию возглавляли люди, служившие в британской армии или колониальных ополчениях и принесшие с собой большую часть британского военного наследия. По мере того, как Война за независимость прогрессировала, французская помощь, ресурсы и военное мышление помогли сформировать новую армию. Несколько европейских солдат пришли сами, чтобы помочь, например, Фридрих Вильгельм фон Штойбен , который обучал прусскую армию тактике и организационным навыкам.

Армия участвовала в многочисленных генеральных сражениях и иногда использовала стратегию Фабиана и тактику «бей и беги» на Юге в 1780 и 1781 годах; под руководством генерал-майора Натанаэля Грина она наносила удары по самым слабым местам британцев, чтобы измотать их силы. Вашингтон одержал победы над британцами в Трентоне и Принстоне , но проиграл ряд сражений в кампании Нью-Йорка и Нью-Джерси в 1776 году и в Филадельфийской кампании в 1777 году. Благодаря решающей победе при Йорктауне и помощи французов Континентальная армия одержала верх над британцами.

После войны Континентальная армия быстро получила земельные сертификаты и была расформирована в ответ на недоверие республиканцев к постоянным армиям. Государственные ополчения стали единственной сухопутной армией новой страны, за исключением полка для охраны Западной границы и одной артиллерийской батареи, охранявшей арсенал Вест-Пойнта . Однако из-за продолжающегося конфликта с коренными американцами вскоре было сочтено необходимым сформировать обученную постоянную армию. Регулярная армия сначала была очень маленькой, и после поражения генерала Сент-Клера в битве при Уобаше [30] , где погибло более 800 солдат, регулярная армия была реорганизована в Легион Соединенных Штатов , созданный в 1791 году и переименованный в Армию Соединенных Штатов в 1796 году.

В 1798 году во время Квази -войны с Францией Конгресс США создал трехлетнюю « Временную армию » численностью 10 000 человек, состоящую из двенадцати полков пехоты и шести отрядов легких драгун . В марте 1799 года Конгресс создал «Окончательную армию» численностью 30 000 человек, включая три полка кавалерии . Обе «армии» существовали только на бумаге, но было закуплено и сохранено снаряжение для 3 000 человек и лошадей. [31]

Война 1812 года , вторая и последняя война между Соединенными Штатами и Великобританией, имела неоднозначные результаты. Армия США не завоевала Канаду, но она уничтожила сопротивление коренных американцев экспансии на Старом Северо-Западе и остановила два крупных британских вторжения в 1814 и 1815 годах. После взятия под контроль озера Эри в 1813 году армия США захватила части западной Верхней Канады, сожгла Йорк и победила Текумсе , что привело к краху его Западной Конфедерации . После побед США в канадской провинции Верхняя Канада британские войска, которые окрестили армию США «Регулярами, ей-богу!», смогли захватить и сжечь Вашингтон , который защищала милиция, в 1814 году. Однако регулярная армия доказала, что она профессиональна и способна победить британскую армию во время вторжений в Платтсбург и Балтимор , что побудило британцев согласиться на ранее отвергнутые условия статус-кво довоенного периода. [ сомнительный – обсудить ] Через две недели после подписания договора (но не ратификации) Эндрю Джексон победил британцев в битве за Новый Орлеан и осаде форта Сент-Филип с армией, в которой преобладали ополченцы и добровольцы, и стал национальным героем. Американские войска и моряки захватили HMS Cyane , Levant и Penguin в последних сражениях войны. Согласно договору, обе стороны (США и Великобритания) вернулись к географическому статус-кво. Оба флота сохранили военные корабли, которые они захватили во время конфликта.

Основная кампания армии против индейцев велась во Флориде против семинолов . Потребовались длительные войны (1818–1858), чтобы окончательно победить семинолов и переселить их в Оклахому. Обычной стратегией в индейских войнах был захват контроля над зимними запасами продовольствия индейцев, но это было бесполезно во Флориде, где не было зимы. Вторая стратегия заключалась в формировании союзов с другими индейскими племенами, но это тоже было бесполезно, потому что семинолы уничтожили всех остальных индейцев, когда они вошли во Флориду в конце восемнадцатого века. [32]

Армия США сражалась и победила в американо-мексиканской войне (1846–1848), которая стала определяющим событием для обеих стран. [33] Победа США привела к приобретению территории, которая в конечном итоге стала полностью или частично штатами Калифорния , Невада , Юта , Колорадо , Аризона , Вайоминг и Нью-Мексико .

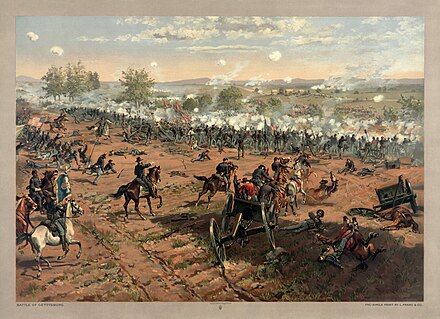

Гражданская война в Америке была самой дорогой войной для США с точки зрения потерь. После того, как большинство рабовладельческих штатов , расположенных на юге США, образовали Конфедеративные Штаты , Армия Конфедеративных Штатов , возглавляемая бывшими офицерами армии США, мобилизовала большую часть белой рабочей силы Юга. Вооруженные силы Соединенных Штатов («Союз» или «Север») сформировали Армию Союза , состоящую из небольшого корпуса регулярных армейских подразделений и большого корпуса добровольческих подразделений, набранных из каждого штата, северного и южного, за исключением Южной Каролины . [34]

В течение первых двух лет силы Конфедерации преуспели в запланированных сражениях, но потеряли контроль над приграничными штатами. [35] У Конфедерации было преимущество в защите большой территории в районе, где болезни уносили вдвое больше жизней, чем боевые действия. Союз следовал стратегии захвата береговой линии, блокады портов и взятия под контроль речных систем. К 1863 году Конфедерация была задушена. Ее восточные армии сражались хорошо, но западные армии терпели поражение одна за другой, пока силы Союза не захватили Новый Орлеан в 1862 году вместе с рекой Теннесси. В Виксбургской кампании 1862–1863 годов генерал Улисс Грант захватил реку Миссисипи и отрезал Юго-Запад. Грант принял командование силами Союза в 1864 году и после серии сражений с очень большими потерями он осадил генерала Роберта Э. Ли в Ричмонде, в то время как генерал Уильям Т. Шерман захватил Атланту и прошел через Джорджию и Каролину . Столица Конфедерации была оставлена в апреле 1865 года, и Ли впоследствии сдал свою армию в здании суда Аппоматтокса. Все остальные армии Конфедерации сдались в течение нескольких месяцев.

Война остается самым смертоносным конфликтом в истории США, в результате которого погибло 620 000 мужчин с обеих сторон. Согласно данным переписи 1860 года, 8% всех белых мужчин в возрасте от 13 до 43 лет погибли в войне, в том числе 6,4% на Севере и 18% на Юге . [36]

После Гражданской войны армия США имела миссию по сдерживанию западных племен коренных американцев в индейских резервациях . Они построили множество фортов и участвовали в последней из индейских войн . Войска армии США также оккупировали несколько южных штатов в эпоху Реконструкции, чтобы защитить вольноотпущенников .

Ключевые сражения испано-американской войны 1898 года велись флотом. Используя в основном новых добровольцев , американские войска победили Испанию в сухопутных кампаниях на Кубе и сыграли центральную роль в филиппино-американской войне .

Начиная с 1910 года армия начала приобретать самолеты с фиксированным крылом . [37] В 1910 году во время Мексиканской революции армия была развернута в городах США вблизи границы, чтобы обеспечить безопасность жизней и имущества. В 1916 году Панчо Вилья , крупный лидер повстанцев, напал на Колумбус, штат Нью-Мексико , что вызвало вмешательство США в дела Мексики до 7 февраля 1917 года. Они сражались с повстанцами и мексиканскими федеральными войсками до 1918 года.

Соединенные Штаты вступили в Первую мировую войну в качестве «ассоциированной державы» в 1917 году на стороне Великобритании , Франции , России , Италии и других союзников . Войска США были отправлены на Западный фронт и участвовали в последних наступлениях, которые завершили войну. С перемирием в ноябре 1918 года армия снова сократила свои силы.

В 1939 году оценки численности армии колебались от 174 000 до 200 000 солдат, что меньше, чем у Португалии , которая по численности занимала 17-е или 19-е место в мире. Генерал Джордж К. Маршалл стал начальником штаба армии в сентябре 1939 года и приступил к расширению и модернизации армии в рамках подготовки к войне. [38] [39]

_March_1944.jpg/440px-U.S._Soldiers_at_Bougainville_(Solomon_Islands)_March_1944.jpg)

Соединенные Штаты вступили во Вторую мировую войну в декабре 1941 года после нападения Японии на Перл-Харбор . Около 11 миллионов американцев должны были служить в различных армейских операциях. [40] [41] На европейском фронте войска армии США составляли значительную часть сил, которые высадились во Французской Северной Африке и заняли Тунис , а затем двинулись на Сицилию и позже сражались в Италии . В высадке в июне 1944 года на севере Франции и в последующем освобождении Европы и разгроме нацистской Германии миллионы солдат армии США сыграли центральную роль. В 1947 году численность солдат в армии США сократилась с восьми миллионов в 1945 году до 684 000 солдат, а общее количество активных дивизий сократилось с 89 до 12. Лидеры армии считали эту демобилизацию успехом. [42]

В Тихоокеанской войне солдаты армии США участвовали вместе с Корпусом морской пехоты США в захвате тихоокеанских островов из-под контроля Японии. После капитуляции стран Оси в мае (Германия) и августе (Япония) 1945 года армейские войска были развернуты в Японии и Германии, чтобы оккупировать две побежденные страны. Через два года после Второй мировой войны Военно -воздушные силы армии отделились от армии, чтобы стать Военно-воздушными силами США в сентябре 1947 года. В 1948 году армия была десегрегирована приказом 9981 президента Гарри С. Трумэна .

_003.jpg/440px-Exercise_Desert_Rock_I_(Buster-Jangle_Dog)_003.jpg)

Конец Второй мировой войны подготовил почву для конфронтации Востока и Запада, известной как Холодная война . С началом Корейской войны возросла обеспокоенность по поводу обороны Западной Европы. Два корпуса, V и VII , были возобновлены под началом Седьмой армии Соединенных Штатов в 1950 году, и численность США в Европе выросла с одной дивизии до четырех. Сотни тысяч американских солдат оставались размещенными в Западной Германии, а другие — в Бельгии , Нидерландах и Великобритании до 1990-х годов в ожидании возможного советского нападения. [43] : минута 9:00–10:00

Во время Холодной войны американские войска и их союзники сражались с коммунистическими силами в Корее и Вьетнаме . Корейская война началась в июне 1950 года, когда Советы покинули заседание Совета Безопасности ООН, сняв свое возможное право вето. Под эгидой Организации Объединенных Наций сотни тысяч американских солдат сражались, чтобы не допустить захвата Южной Кореи Северной Кореей , а затем и вторжения в северную страну. После неоднократных наступлений и отступлений с обеих сторон и вступления в войну Китайской народной добровольческой армии , Соглашение о перемирии в Корее вернуло полуостров к статус-кво в июле 1953 года.

Вьетнамская война часто рассматривается как низшая точка для армии США из-за использования призывного персонала , непопулярности войны среди общественности США и разочаровывающих ограничений, наложенных на армию политическими лидерами США. Хотя американские войска были размещены в Южном Вьетнаме с 1959 года в разведывательных и консультационных/учебных ролях, они не были развернуты в больших количествах до 1965 года, после инцидента в заливе Тонкин . Американские войска эффективно установили и удерживали контроль над «традиционным» полем боя, но они изо всех сил пытались противостоять партизанской тактике ударов и отступлений коммунистического Вьетконга и Народной армии Вьетнама (NVA) . [44] [45]

В 1960-х годах Министерство обороны продолжало внимательно изучать резервные силы и подвергать сомнению количество дивизий и бригад, а также избыточность содержания двух резервных компонентов, Национальной гвардии армии и Резерва армии . [46] В 1967 году министр обороны Роберт Макнамара решил, что 15 боевых дивизий в Национальной гвардии армии были излишними, и сократил их количество до восьми дивизий (одна механизированная пехотная, две бронетанковые и пять пехотных), но увеличил количество бригад с семи до 18 (одна воздушно-десантная, одна бронетанковая, две механизированные пехотные и 14 пехотных). Потеря дивизий не устроила штаты. Их возражения включали неадекватное сочетание маневренных элементов для тех, которые остались, и прекращение практики ротации команд дивизий среди штатов, которые их поддерживали. Согласно предложению, оставшиеся командиры дивизий должны были проживать в штате базы дивизии. Однако никакого сокращения общей численности Национальной гвардии армии не произошло, что убедило губернаторов принять план. Штаты реорганизовали свои силы соответствующим образом в период с 1 декабря 1967 года по 1 мая 1968 года.

Политика тотальной силы была принята начальником штаба армии генералом Крейтоном Абрамсом после войны во Вьетнаме и включала рассмотрение трех компонентов армии — регулярной армии , национальной гвардии и резерва армии как единой силы. [47] Переплетение генералом Абрамсом трех компонентов армии фактически сделало невозможным проведение расширенных операций без участия как национальной гвардии армии, так и резерва армии в преимущественно боевой поддержке. [48] Армия была преобразована в полностью добровольческую силу с большим акцентом на обучение в соответствии с конкретными стандартами эффективности, обусловленными реформами генерала Уильяма Э. Депюи , первого командующего Командования по обучению и доктрине армии США . После Кэмп-Дэвидских соглашений, подписанных Египтом и Израилем при посредничестве президента Джимми Картера в 1978 году, в рамках соглашения и Соединенные Штаты, и Египет договорились о проведении совместных военных учений под руководством обеих стран, которые обычно проводились каждые 2 года; эти учения известны как учения Bright Star .

1980-е годы были в основном десятилетием реорганизации. Закон Голдуотера-Николса 1986 года создал объединенные боевые командования, объединив армию с другими четырьмя военными службами под едиными, географически организованными командными структурами. Армия также сыграла свою роль во вторжениях в Гренаду в 1983 году ( операция Urgent Fury ) и Панаму в 1989 году ( операция Just Cause ).

К 1989 году Германия приближалась к воссоединению , а Холодная война подходила к концу. Армейское руководство отреагировало, начав планировать сокращение численности. К ноябрю 1989 года информаторы Пентагона изложили планы по сокращению конечной численности армии на 23%, с 750 000 до 580 000 человек. [49] Был использован ряд стимулов, таких как ранний выход на пенсию.

В 1990 году Ирак вторгся в своего меньшего соседа, Кувейт , и сухопутные войска США быстро развернулись, чтобы обеспечить защиту Саудовской Аравии . В январе 1991 года началась операция «Буря в пустыне» , возглавляемая США коалиция, которая развернула более 500 000 солдат, большую часть из которых составляли формирования армии США, чтобы вытеснить иракские войска . Кампания закончилась полной победой, поскольку силы западной коалиции разгромили иракскую армию . Некоторые из крупнейших танковых сражений в истории произошли во время войны в Персидском заливе. Битва за Медину-Ридж , Битва за Норфолк и Битва за 73 Истинга были танковыми сражениями исторического значения. [50] [51] [52]

После операции «Буря в пустыне» армия не участвовала в крупных боевых операциях до конца 1990-х годов, но участвовала в ряде миротворческих операций. В 1990 году Министерство обороны выпустило руководство по «перебалансировке» после обзора политики тотальной силы, [53] но в 2004 году ученые из Военно-воздушного колледжа ВВС США пришли к выводу, что руководство отменит политику тотальной силы, которая является «необходимым компонентом для успешного применения военной силы». [54]

.jpg/440px-Flickr_-_DVIDSHUB_-_Operation_in_Nahr-e_Saraj_(Image_5_of_7).jpg)

11 сентября 2001 года 53 гражданских лица армии (47 сотрудников и шесть подрядчиков) и 22 солдата были среди 125 жертв, убитых в Пентагоне в результате террористической атаки , когда рейс 77 American Airlines, захваченный пятью угонщиками из Аль-Каиды, врезался в западную сторону здания в рамках атак 11 сентября . [55] В ответ на атаки 11 сентября и в рамках Глобальной войны с террором силы США и НАТО вторглись в Афганистан в октябре 2001 года, сместив правительство Талибана . Армия США также возглавила объединенное вторжение США и союзников в Ирак в 2003 году; она служила основным источником для наземных войск с ее способностью поддерживать краткосрочные и долгосрочные операции по развертыванию. В последующие годы миссия изменилась с конфликта между регулярными военными на борьбу с повстанцами , что привело к гибели более 4000 военнослужащих США (по состоянию на март 2008 года) и ранениям еще тысяч. [56] [57] В период с 2003 по 2011 год в Ираке было убито 23 813 повстанцев. [58]

До 2009 года главным планом модернизации армии, самым амбициозным со времен Второй мировой войны, [59] была программа Future Combat Systems . В 2009 году многие системы были отменены, а оставшиеся были включены в программу модернизации BCT . [60] К 2017 году проект Brigade Modernization был завершен, а его штаб, Brigade Modernization Command, был переименован в Joint Modernization Command, или JMC. [61] В ответ на секвестр бюджета в 2013 году планы армии должны были сократиться до уровня 1940 года, [62] хотя фактическая конечная численность действующей армии, как прогнозировалось, должна была сократиться до примерно 450 000 военнослужащих к концу 2017 финансового года. [63] [64] С 2016 по 2017 год армия сняла с вооружения сотни вертолетов наблюдения OH-58 Kiowa Warrior , [65] сохранив при этом свои боевые вертолеты Apache. [66] Расходы на исследования, разработки и закупки армии в 2015 году изменились с 32 миллиардов долларов, запланированных в 2012 году на 2015 финансовый год, до 21 миллиарда долларов на 2015 финансовый год, ожидаемых в 2014 году. [67]

К 2017 году была сформирована целевая группа для решения вопросов модернизации армии, [68] что вызвало перемещение подразделений: CCDC и ARCIC , из Командования материального обеспечения армии (AMC) и Командования по подготовке и доктрине армии (TRADOC) соответственно, в новое Командование армии (ACOM) в 2018 году. [69] Командование будущего армии (AFC) является аналогом FORSCOM, TRADOC и AMC, других ACOM. [70] Миссия AFC — реформа модернизации: проектирование оборудования, а также работа в рамках процесса закупок, который определяет материальные средства для AMC. Миссия TRADOC — определение архитектуры и организации армии, а также обучение и снабжение солдат для FORSCOM. [71] : минуты 2:30–15:00 [43] Межфункциональные группы (CFT) AFC являются средством Командования будущего для устойчивой реформы процесса закупок в будущем. [72] Для поддержки приоритетов модернизации армии в бюджете на 2020 финансовый год было выделено 30 миллиардов долларов на шесть главных приоритетов модернизации в течение следующих пяти лет. [73] 30 миллиардов долларов были получены за счет 8 миллиардов долларов избежания расходов и 22 миллиардов долларов из прекращений. [73]

Задача организации армии США началась в 1775 году. [75] В первые сто лет своего существования армия США поддерживалась как небольшая сила мирного времени для укомплектования постоянных фортов и выполнения других невоенных обязанностей, таких как инженерные и строительные работы. Во время войны армия США пополнялась гораздо более многочисленными добровольцами США , которые были сформированы независимо различными правительствами штатов. Штаты также содержали постоянные ополчения , которые также могли быть призваны на службу в армию.

К двадцатому веку армия США мобилизовала американских добровольцев четыре раза во время каждой из крупных войн девятнадцатого века. Во время Первой мировой войны была организована « Национальная армия » для борьбы с конфликтом, заменив концепцию американских добровольцев. [76] Она была демобилизована в конце Первой мировой войны и заменена Регулярной армией, Организованным резервным корпусом и государственными ополчениями. В 1920-х и 1930-х годах «карьерные» солдаты были известны как « Регулярная армия », а «Корпус рядового резерва» и «Корпус офицерского резерва» были увеличены для заполнения вакансий при необходимости. [77]

В 1941 году была основана « Армия Соединенных Штатов » для ведения боевых действий во Второй мировой войне. [78] Регулярная армия, армия Соединенных Штатов, Национальная гвардия и офицерский/рядовой резервный корпус (ORC и ERC) существовали одновременно. После Второй мировой войны ORC и ERC были объединены в резерв армии Соединенных Штатов . Армия Соединенных Штатов была восстановлена для Корейской войны и войны во Вьетнаме и была демобилизована после приостановки призыва . [ 77]

В настоящее время армия делится на регулярную армию , резерв армии и национальную гвардию армии . [76] Некоторые штаты также содержат силы обороны штата как тип резерва национальной гвардии, в то время как все штаты сохраняют правила для государственных ополчений . [79] Государственные ополчения бывают как «организованными», что означает, что они являются вооруженными силами, обычно входящими в состав сил обороны штата, так и «неорганизованными», что просто означает, что все годные к военной службе мужчины могут быть призваны на военную службу.

Армия США также разделена на несколько подразделений и функциональных областей . Подразделения включают офицеров, уорент-офицеров и рядовых солдат, в то время как функциональные области состоят из офицеров, которые переклассифицированы из своего бывшего подразделения в функциональное подразделение. Тем не менее, офицеры продолжают носить знаки различия своего бывшего подразделения в большинстве случаев, поскольку функциональные области, как правило, не имеют отдельных знаков различия. Некоторые подразделения, такие как силы специального назначения , действуют аналогично функциональным областям в том смысле, что люди не могут присоединиться к ним, пока не отслужат в другом армейском подразделении. Карьера в армии может распространяться на кросс-функциональные области для офицера, [80] уорент-офицера, рядового и гражданского персонала.

До 1933 года члены Национальной гвардии армии считались государственным ополчением, пока не были мобилизованы в армию США, как правило, в начале войны. После поправки 1933 года к Закону о национальной обороне 1916 года все солдаты Национальной гвардии армии имели двойной статус. Они служат в качестве национальных гвардейцев под руководством губернатора своего штата или территории и в качестве резервистов армии США под руководством президента, в Национальной гвардии армии Соединенных Штатов. [82]

Since the adoption of the total force policy, in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, reserve component soldiers have taken a more active role in U.S. military operations. For example, Reserve and Guard units took part in the Gulf War, peacekeeping in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

![]() Headquarters, United States Department of the Army (HQDA):

Headquarters, United States Department of the Army (HQDA):

See Structure of the United States Army for a detailed treatment of the history, components, administrative and operational structure and the branches and functional areas of the Army.

The U.S. Army is made up of three components: the active component, the Regular Army; and two reserve components, the Army National Guard and the Army Reserve. Both reserve components are primarily composed of part-time soldiers who train once a month – known as battle assemblies or unit training assemblies (UTAs) – and conduct two to three weeks of annual training each year. Both the Regular Army and the Army Reserve are organized under Title 10 of the United States Code, while the National Guard is organized under Title 32. While the Army National Guard is organized, trained and equipped as a component of the U.S. Army, when it is not in federal service it is under the command of individual state and territorial governors. However, the District of Columbia National Guard reports to the U.S. president, not the district's mayor, even when not federalized. Any or all of the National Guard can be federalized by presidential order and against the governor's wishes.[119]

The U.S. Army is led by a civilian secretary of the Army, who has the statutory authority to conduct all the affairs of the army under the authority, direction and control of the secretary of defense.[120] The chief of staff of the Army, who is the highest-ranked military officer in the army, serves as the principal military adviser and executive agent for the secretary of the Army, i.e., its service chief; and as a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, a body composed of the service chiefs from each of the four military services belonging to the Department of Defense who advise the president of the United States, the secretary of defense and the National Security Council on operational military matters, under the guidance of the chairman and vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[121][122] In 1986, the Goldwater–Nichols Act mandated that operational control of the services follows a chain of command from the president to the secretary of defense directly to the unified combatant commanders, who have control of all armed forces units in their geographic or function area of responsibility, thus the secretaries of the military departments (and their respective service chiefs underneath them) only have the responsibility to organize, train and equip their service components. The army provides trained forces to the combatant commanders for use as directed by the secretary of defense.[123]

By 2013, the army shifted to six geographical commands that align with the six geographical unified combatant commands (CCMD):

The army also transformed its base unit from divisions to brigades. Division lineage will be retained, but the divisional headquarters will be able to command any brigade, not just brigades that carry their divisional lineage. The central part of this plan is that each brigade will be modular, i.e., all brigades of the same type will be exactly the same and thus any brigade can be commanded by any division. As specified before the 2013 end-strength re-definitions, the three major types of brigade combat teams are:

In addition, there are combat support and service support modular brigades. Combat support brigades include aviation (CAB) brigades, which will come in heavy and light varieties, fires (artillery) brigades (now transforms to division artillery) and expeditionary military intelligence brigades. Combat service support brigades include sustainment brigades and come in several varieties and serve the standard support role in an army.

The U.S. Army's conventional combat capability currently consists of 11 active divisions and 1 deployable division headquarters (7th Infantry Division) as well as several independent maneuver units.

From 2013 through 2017, the Army sustained organizational and end-strength reductions after several years of growth. In June 2013, the Army announced plans to downsize to 32 active brigade combat teams by 2015 to match a reduction in active-duty strength to 490,000 soldiers. Army chief of staff Raymond Odierno projected that the Army was to shrink to "450,000 in the active component, 335,000 in the National Guard and 195,000 in U.S. Army Reserve" by 2018.[129] However, this plan was scrapped by the incoming Trump administration, with subsequent plans to expand the Army by 16,000 soldiers to a total of 476,000 by October 2017. The National Guard and the Army Reserve will see a smaller expansion.[130][131]

The Army's maneuver organization was most recently altered by the reorganization of United States Army Alaska into the 11th Airborne Division, transferring the 1st and 4th Brigade Combat Teams of the 25th Infantry Division under a separate operational headquarters to reflect the brigades' distinct, Arctic-oriented mission. As part of the reorganization, the 1–11 (formerly 1–25) Stryker Brigade Combat Team will reorganize as an Infantry Brigade Combat Team.[132] Following this transition, the active component BCTs will number 11 Armored brigades, 6 Stryker brigades, and 14 Infantry brigades.

Within the Army National Guard and United States Army Reserve, there are a further eight divisions, 27 brigade combat teams, additional combat support and combat service support brigades, and independent cavalry, infantry, artillery, aviation, engineer and support battalions. The Army Reserve in particular provides virtually all psychological operations and civil affairs units.

![]() United States Army Forces Command (FORSCOM)

United States Army Forces Command (FORSCOM)

For a description of U.S. Army tactical organizational structure, see: a U.S. context[broken anchor] and also a global context.

![]() United States Army Special Operations Command (Airborne) (USASOC):[147]

United States Army Special Operations Command (Airborne) (USASOC):[147]

The United States Army Medical Department (AMEDD), formerly the Army Medical Service (AMS), is the primary healthcare organization of the United States Army and is led by the Surgeon General of the United States Army (TSG), a three-star lieutenant general, who (by policy) also serves as the Commanding General, United States Army Medical Command (MEDCOM). TSG is assisted by a Deputy Surgeon General and a full staff, the Office of the Surgeon General (OTSG). The incumbent Surgeon General is Lieutenant General Mary K. Izaguirre (since January 25, 2024).[154]

AMEDD encompasses the Army's six non-combat, medical-focused specialty branches (or "Corps"), these branches are: the Medical Corps, Nurse Corps, Dental Corps, Veterinary Corps, Medical Specialist Corps. Each of these branches is headed by a Corps Chief that reports directly to the Surgeon General.[155][156][157][158][159]

The Army's Talent Management Task Force (TMTF) has deployed IPPS-A,[160] the Integrated Personnel and Pay System - Army, an app which serves the National Guard, and on 17 January 2023 the Army Reserve and Active Army.[161] Soldiers were reminded to update their information using the legacy systems to keep their payroll and personnel information current by December 2021. IPPS-A is the Human Resources system for the Army, is now available for download for Android, or the Apple store.[162] It will be used for future promotions and other personnel decisions. Among the changes are:

Below are the U.S. Army ranks authorized for use today and their equivalent NATO designations. Although no living officer currently holds the rank of General of the Army, it is still authorized by Congress for use in wartime.

There are several paths to becoming a commissioned officer[167] including the United States Military Academy,[168] Reserve Officers' Training Corps,[169] Officer Candidate School,[170] and direct commissioning. Regardless of which road an officer takes, the insignia are the same. Certain professions including physicians, pharmacists, nurses, lawyers and chaplains are commissioned directly into the Army.

Most army commissioned officers (those who are generalists)[171] are promoted based on an "up or out" system. A more flexible talent management process is underway.[171] The Defense Officer Personnel Management Act of 1980 establishes rules for the timing of promotions and limits the number of officers that can serve at any given time.[172]

Army regulations call for addressing all personnel with the rank of general as "General (last name)" regardless of the number of stars. Likewise, both colonels and lieutenant colonels are addressed as "Colonel (last name)" and first and second lieutenants as "Lieutenant (last name)".[173]

Warrant officers[167] are single track, specialty officers with subject matter expertise in a particular area. They are initially appointed as warrant officers (in the rank of WO1) by the secretary of the Army, but receive their commission upon promotion to chief warrant officer two (CW2).

By regulation, warrant officers are addressed as "Mr. (last name)" or "Ms. (last name)" by senior officers and as "sir" or "ma'am" by all enlisted personnel.[173] However, many personnel address warrant officers as "Chief (last name)" within their units regardless of rank.

Sergeants and corporals are referred to as NCOs, short for non-commissioned officers.[167][174] This distinguishes corporals from the more numerous specialists who have the same pay grade but do not exercise leadership responsibilities. Beginning in 2021, all corporals will be required to conduct structured self-development for the NCO ranks, completing the basic leader course (BLC), or else be laterally assigned as specialists. Specialists who have completed BLC and who have been recommended for promotion will be permitted to wear corporal rank before their recommended promotion as NCOs.[175]

Privates and privates first class (E3) are addressed as "Private (last name)", specialists as "Specialist (last name)", corporals as "Corporal (last name)" and sergeants, staff sergeants, sergeants first class and master sergeants all as "Sergeant (last name)". First sergeants are addressed as "First Sergeant (last name)" and sergeants major and command sergeants major are addressed as "Sergeant Major (last name)".[173][176]

Training in the U.S. Army is generally divided into two categories – individual and collective. Because of COVID-19 precautions, the first two weeks of basic training — not including processing and out-processing – incorporate social distancing and indoor desk-oriented training. Once the recruits have tested negative for COVID-19 for two weeks, the remaining 8 weeks follow the traditional activities for most recruits,[178] followed by Advanced Individualized Training (AIT) where they receive training for their military occupational specialties (MOS).[179] Some individual's MOSs range anywhere from 14 to 20 weeks of One Station Unit Training (OSUT), which combines Basic Training and AIT. The length of AIT school varies by the MOS. The length of time spent in AIT depends on the MOS of the soldier. Certain highly technical MOS training requires many months (e.g., foreign language translators). Depending on the needs of the army, Basic Combat Training for combat arms soldiers is conducted at a number of locations, but two of the longest-running are the Armor School and the Infantry School, both at Fort Moore, Georgia. Sergeant Major of the Army Dailey notes that an infantrymen's pilot program for One Station Unit Training (OSUT) extends 8 weeks beyond Basic Training and AIT, to 22 weeks. The pilot, designed to boost infantry readiness ended in December 2018. The new Infantry OSUT covered the M240 machine gun as well as the M249 squad automatic weapon.[180] The redesigned Infantry OSUT started in 2019.[181][182] Depending on the result of the 2018 pilot, OSUTs could also extend training in other combat arms beyond the infantry.[181] One Station Unit Training will be extended to 22 weeks for Armor by Fiscal Year 2021.[24] Additional OSUTs are expanding to Cavalry, Engineer, and Military Police (MP) in the succeeding Fiscal Years.[183]

A new training assignment for junior officers was instituted, that they serve as platoon leaders for Basic Combat Training (BCT) platoons.[184] These lieutenants will assume many of the administrative, logistical, and day-to-day tasks formerly performed by the drill sergeants of those platoons and are expected to "lead, train, and assist with maintaining and enhancing the morale, welfare and readiness" of the drill sergeants and their BCT platoons.[184] These lieutenants are also expected to stem any inappropriate behaviors they witness in their platoons, to free up the drill sergeants for training.[184]

The United States Army Combat Fitness Test (ACFT) was introduced in 2018 to 60 battalions spread throughout the Army.[185] The test and scoring system is the same for all soldiers, regardless of gender. It takes an hour to complete, including resting periods.[186] The ACFT supersedes the Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT),[187][188][189] as being more relevant to survival in combat.[185] Six events were determined to better predict which muscle groups of the body were adequately conditioned for combat actions:[186] three deadlifts,[190] a standing power throw of a ten-pound medicine ball,[191] hand-release pushups[192] (which replace the traditional pushup), a sprint/drag/carry 250 yard event,[193] three pull-ups with leg tucks (or a plank test in lieu of the leg tuck),[194][195] a mandatory rest period, and a two-mile run.[196] As of 1 October 2020 all soldiers from all three components (Regular Army, Reserve, and National Guard)[197] are subject to this test.[198][199] The ACFT now tests all soldiers in basic training as of October 2020. The ACFT became the official test of record 1 October 2020; before that day every Army unit was required to complete a diagnostic ACFT[200] (All Soldiers with valid APFT scores can use them until March 2022. The Holistic Health and Fitness (H2F) System is one way that soldiers can prepare.).[201][202][203] The ACFT movements directly translate to movements on the battlefield.[182]Following their basic and advanced training at the individual level, soldiers may choose to continue their training and apply for an "additional skill identifier" (ASI). The ASI allows the army to take a wide-ranging MOS and focus it on a more specific MOS. For example, a combat medic, whose duties are to provide pre-hospital emergency treatment, may receive ASI training to become a cardiovascular specialist, a dialysis specialist, or even a licensed practical nurse. For commissioned officers, training includes pre-commissioning training, known as Basic Officer Leader Course A, either at USMA or via ROTC, or by completing OCS. After commissioning, officers undergo branch-specific training at the Basic Officer Leaders Course B, (formerly called Officer Basic Course), which varies in time and location according to their future assignments. Officers will continue to attend standardized training at different stages of their careers.[204]

Collective training at the unit level takes place at the unit's assigned station, but the most intensive training at higher echelons is conducted at the three combat training centers (CTC); the National Training Center (NTC) at Fort Irwin, California, the Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) at Fort Johnson, Louisiana and the Joint Multinational Training Center (JMRC) at the Hohenfels Training Area in Hohenfels and Grafenwöhr,[205] Germany. ReARMM is the Army Force Generation process approved in 2020 to meet the need to continuously replenish forces for deployment, at unit level and for other echelons as required by the mission. Individual-level replenishment still requires training at a unit level, which is conducted at the continental U.S. (CONUS) replacement center (CRC) at Fort Bliss, in New Mexico and Texas before their individual deployment.[206]

Chief of Staff Milley notes that the Army is suboptimized for training in cold-weather regions, jungles, mountains, or urban areas where in contrast the Army does well when training for deserts or rolling terrain.[207]: minute 1:26:00 Post 9/11, Army unit-level training was for counter-insurgency (COIN); by 2014–2017, training had shifted to decisive action training.[208]

The chief of staff of the Army has identified six modernization priorities, these being (in order): artillery, ground vehicles, aircraft, network, air/missile defense, and soldier lethality.[209]

_interceptors_is_launched_during_a_successful_intercept_test_-_US_Army.jpg/440px-The_first_of_two_Terminal_High_Altitude_Area_Defense_(THAAD)_interceptors_is_launched_during_a_successful_intercept_test_-_US_Army.jpg)

The United States Army employs various weapons to provide light firepower at short ranges. The most common weapon type used by the army is the M4 carbine, a compact variant of the M16 rifle,[210] along with the 7.62×51mm variant of the FN SCAR for Army Rangers.Then the future weapon is the M7, which fires a 6.8mm round. The primary sidearm in the U.S. Army is the 9 mm M9 pistol; the M11 pistol is also used.[211] Both handguns are to be replaced by the M17[212] through the Modular Handgun System program.[213] Soldiers are also equipped with various hand grenades, such as the M67 fragmentation grenade and M18 smoke grenade.[214][215]

Many units are supplemented with a variety of specialized weapons, including the M249 SAW (Squad Automatic Weapon), to provide suppressive fire at the squad level.[216] Indirect fire is provided by the M320 grenade launcher.[217] The M1014 Joint Service Combat Shotgun or the Mossberg 590 Shotgun are used for door breaching and close-quarters combat. The M14EBR is used by designated marksmen. Snipers use the M107 Long Range Sniper Rifle, the M2010 Enhanced Sniper Rifle and the M110 Semi-Automatic Sniper Rifle.[218]

The army employs various crew-served weapons to provide heavy firepower at ranges exceeding that of individual weapons.

The M240 is the U.S. Army's standard Medium Machine Gun.[219] The M2 heavy machine gun is generally used as a vehicle-mounted machine gun. In the same way, the 40 mm MK 19 grenade machine gun is mainly used by motorized units.[220]

The U.S. Army uses three types of mortar for indirect fire support when heavier artillery may not be appropriate or available. The smallest of these is the 60 mm M224, normally assigned at the infantry company level.[221] At the next higher echelon, infantry battalions are typically supported by a section of 81 mm M252 mortars.[222] The largest mortar in the army's inventory is the 120 mm M120/M121, usually employed by mechanized units.[223]

Fire support for light infantry units is provided by towed howitzers, including the 105 mm M119A1[224] and the 155 mm M777.[225]

The U.S. Army utilizes a variety of direct-fire rockets and missiles to provide infantry with an Anti-Armor Capability. The AT4 is an unguided projectile that can destroy armor and bunkers at ranges up to 500 meters.[226] The FIM-92 Stinger is a shoulder-launched, heat seeking anti-aircraft missile.[227] The FGM-148 Javelin and BGM-71 TOW are anti-tank guided missiles.[228][229]

U.S. Army doctrine puts a premium on mechanized warfare. It fields the highest vehicle-to-soldier ratio in the world as of 2009.[230] The army's most common vehicle is the High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV), commonly called the Humvee, which is capable of serving as a cargo/troop carrier, weapons platform and ambulance, among many other roles.[231] While they operate a wide variety of combat support vehicles, one of the most common types centers on the family of HEMTT vehicles. The M1A2 Abrams is the army's main battle tank,[232] while the M2A3 Bradley is the standard infantry fighting vehicle.[233] Other vehicles include the Stryker,[234] the M113 armored personnel carrier[235] and multiple types of Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles.[236]

The U.S. Army's principal artillery weapons are the M109A7 Paladin self-propelled howitzer[237] and the M270 multiple launch rocket system (MLRS),[238] both mounted on tracked platforms and assigned to heavy mechanized units.

While the United States Army Aviation Branch operates a few fixed-wing aircraft, it mainly operates several types of rotary-wing aircraft. These include the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter,[239] the UH-60 Black Hawk utility tactical transport helicopter[240] and the CH-47 Chinook heavy-lift transport helicopter.[241] Restructuring plans call for reduction of 750 aircraft and from seven to four types.[242] The Army is evaluating two fixed-wing aircraft demonstrators; ARES, and Artemis are under evaluation to replace the Guardrail ISR (Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) aircraft.[243] Under the Johnson-McConnell agreement of 1966, the Army agreed to limit its fixed-wing aviation role to administrative mission support (light unarmed aircraft which cannot operate from forward positions). For UAVs, the Army is deploying at least one company of drone MQ-1C Gray Eagles to each Active Army division.[244]

The Army Combat Uniform (ACU) currently features a camouflage pattern known as Operational Camouflage Pattern (OCP); OCP replaced a pixel-based pattern known as Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP) in 2019.

On 11 November 2018, the Army announced a new version of 'Army Greens' based on uniforms worn during World War II that will become the standard garrison service uniform.[245] The blue Army Service Uniform will remain as the dress uniform. The Army Greens are projected to be first fielded in the summer of 2020.[245][needs update]

The beret flash of enlisted personnel displays their distinctive unit insignia (shown above). The U.S. Army's black beret is no longer worn with the ACU for garrison duty, having been permanently replaced with the patrol cap. After years of complaints that it was not suited well for most work conditions, Army Chief of Staff General Martin Dempsey eliminated it for wear with the ACU in June 2011. Soldiers who are currently in a unit in jump status still wear berets, whether the wearer is parachute-qualified or not (maroon beret), while members of Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs) wear brown berets. Members of the 75th Ranger Regiment and the Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade (tan beret) and Special Forces (rifle green beret) may wear it with the Army Service Uniform for non-ceremonial functions. Unit commanders may still direct the wear of patrol caps in these units in training environments or motor pools.

The Army has relied heavily on tents to provide the various facilities needed while on deployment (Force Provider Expeditionary (FPE)).[209]: p.146 The most common tent uses for the military are as temporary barracks (sleeping quarters), DFAC buildings (dining facilities),[246] forward operating bases (FOBs), after-action review (AAR), tactical operations center (TOC), morale, welfare and recreation (MWR) facilities, as well as security checkpoints. Furthermore, most of these tents are set up and operated through the support of Natick Soldier Systems Center. Each FPE contains billeting, latrines, showers, laundry and kitchen facilities for 50–150 Soldiers,[209]: p.146 and is stored in Army Prepositioned Stocks 1, 2, 4 and 5. This provisioning allows combatant commanders to position soldiers as required in their Area of Responsibility, within 24 to 48 hours.

The U.S. Army is beginning to use a more modern tent called the deployable rapid assembly shelter (DRASH). In 2008, DRASH became part of the Army's Standard Integrated Command Post System.[247]

Subject: "Order of Precedence of Members of Armed Forces of the United States When in Formation" (Paragraph 3. PRESCRIBED PROCEDURE)

World War II: 10.42 million (1 December 1941-31 August 1945). Other sources count the Army of Occupation up to 31 December 1946. By 30 June 1947 the Army's strength was down to 990,000 troops.

10.4 million

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)