An authoritarian military dictatorship ruled Chile for seventeen years, between 11 September 1973 and 11 March 1990. The dictatorship was established after the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende was overthrown in a coup d'état backed by the United States on 11 September 1973. During this time, the country was ruled by a military junta headed by General Augusto Pinochet. The military used the breakdown of democracy and the economic crisis that took place during Allende's presidency to justify its seizure of power. The dictatorship presented its mission as a "national reconstruction". The coup was the result of multiple forces, including pressure from conservative groups, certain political parties, union strikes and other domestic unrest, as well as international factors.[A]

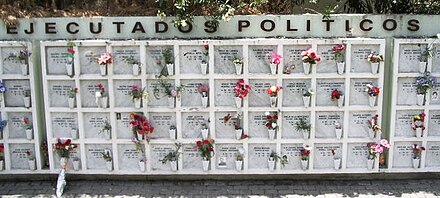

The regime was characterized by the systematic suppression of political parties and the persecution of dissidents to an extent unprecedented in the history of Chile. Overall, the regime left over 3,000 dead or missing, tortured tens of thousands of prisoners,[2] and drove an estimated 200,000 Chileans into exile.[3] The dictatorship's effects on Chilean political and economic life continue to be felt. Two years after its ascension, neoliberal economic reforms were implemented in sharp contrast to Allende's leftist policies. The government was advised by the Chicago Boys, a team of free-market economists educated in the United States. Later, in 1980, the regime replaced the 1925 Constitution with a new constitution in a controversial referendum. This established a series of provisions that would eventually lead to the 1988 Chilean national plebiscite on October 5 of that year.

In that plebiscite, 55% of voters rejected the proposal of extending Pinochet's presidency for another eight years. Consequently, democratic presidential and parliamentary elections were held the following year. The military dictatorship ended in 1990 with the election of Christian Democrat candidate Patricio Aylwin. However, the military remained out of civilian control for several years after the junta itself had lost power.[4][5]

There has been a large amount of debate over the extent of US government involvement in destabilising the Allende government.[6][7] Recently declassified documents show evidence of communication between the Chilean military and United States officials, suggesting covert US involvement in assisting the military's rise to power. Some key figures in the Nixon administration, such as Henry Kissinger, used the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to mount a major destabilization campaign.[8] As the CIA revealed in 2000, "In the 1960s and the early 1970s, as part of the US Government policy to try to influence events in Chile, the CIA undertook specific covert action projects in Chile ... to discredit Marxist-leaning political leaders, especially Dr. Salvador Allende, and to strengthen and encourage their civilian and military opponents to prevent them from assuming power".[9] The CIA worked with right-wing Chilean politicians, military personnel, and journalists to undermine socialism in Chile.[10] One reason for this was financial, as many US businesses had investments in Chile, and Allende's socialist policies included the nationalization of Chile's major industries. Another reason was the propagandized fear of the spread of communism, which was particularly important in the context of the Cold War. The rationale was that US feared that Allende would promote the spreading of Soviet influence in their 'backyard'.[11] As early as 1963, the U.S. via the CIA and U.S. multinationals such as ITT intervened in Chilean politics using a variety of tactics and millions of dollars to interfere with elections, ultimately helping plan the coup against Allende.[12][13][14]

On 15 April 1973, workers from the El Teniente mining camp had ceased working, demanding higher wages. The strike lasted 76 days and cost the government severely in lost revenues. One of the strikers, Luis Bravo Morales, was shot dead in Rancagua city. On June 29, the Blindados No. 2 tank regiment under the command of Colonel Roberto Souper, attacked La Moneda, Chile's presidential palace. Instigated by the neo-fascist organization Fatherland and Liberty, the armoured cavalry soldiers hoped other units would be inspired to join them. Instead, armed units led by generals Carlos Prats and Augusto Pinochet quickly put down the coup attempt. In late July, 40,000 truckers, squeezed by price controls and rising costs, tied up transportation in a nationwide strike that lasted 37 days, costing the government US$6 million a day.[15] Two weeks before the coup, public dissatisfaction with rising prices and food shortages led to protests like the one at the Plaza de la Constitución which had been dispersed with tear gas.[16] Allende also clashed with Chile's largest circulation newspaper, the CIA-funded El Mercurio.[B] The newspaper was investigated for tax evasion and its director arrested and interviewed.[18] The Allende government found it impossible to control inflation, which grew to more than 300 percent by September,[19] further dividing Chileans over the Allende government and its policies.

Upper- and middle-class right-wing women also played a role in the opposition against the Allende government. They co-ordinated two prominent opposition groups called El Poder Feminino ("female power"), and Solidaridad, Orden y Libertad ("solidarity, order, and freedom").[20][21] The women carried out the ‘March of the Empty Pots and Pans’ in December 1971.

On August 22, 1973, the Chamber of Deputies passed, by a vote of 81 to 47, a resolution calling for President Allende to respect the constitution. The measure failed to obtain the two-thirds majority in the Senate constitutionally required to convict the president of abuse of power, but the resolution still represented a challenge to Allende's legitimacy. The military viewed themselves as guarantors of the constitution and elements within the armed forces considered that Allende had lost legitimacy as Chile's leader.[22] As a result, reacting to demand for intervention from opponents of the government, the military began planning for a military coup which would ultimately take place on September 11, 1973. Contrary to popular belief, Pinochet was not the mastermind behind the coup. It was, in fact, naval officers who first decided that military intervention was necessary to remove President Allende from power.[23] Army generals were unsure of Pinochet's allegiances, as he had given no prior indication of disloyalty to Allende, and thus was only informed of these plans on the evening of 8 September, just three days before the coup took place.[24] On 11 September 1973, the military launched a coup, with troops surrounding La Moneda Palace. Allende died that day of suspected suicide.

The military installed themselves in power as a Military Government Junta, composed of the heads of the Army, Navy, Air Force and Carabineros (police). Once the Junta was in power, General Augusto Pinochet soon consolidated his control over the government. Since he was the commander-in-chief of the oldest branch of the military forces (the Army), he was made the titular head of the junta, and soon after President of Chile. Once the junta had taken over, the United States immediately recognized the new regime and helped it consolidate power.[8]

On September 13, the junta dissolved the Congress and outlawed or suspended all political activities in addition to suspending the 1925 constitution. All political activity was declared "in recess". The Government Junta immediately banned the socialist, Marxist and other leftist parties that had constituted former President Allende's Popular Unity coalition[25] and began a systemic campaign of imprisonment, torture, harassment and/or murder against the perceived opposition. Eduardo Frei, Allende's predecessor as president, initially supported the coup along with his Christian Democratic colleagues. However, they later assumed the role of a loyal opposition to the military rulers. During 1976–77, this repression even reached independent and Christian Democrat labour leaders who had supported the coup, several were exiled.[26] Christian Democrats like Radomiro Tomic were jailed or forced into exile.[27][28] Retired military personnel were named rectors of universities and they carried out vast purges of suspected left-wing sympathisers.[29] With such strong repression, the Catholic church became the only public voice allowed within Chile. By 1974, the Commission of Peace had established a large network to provide information to numerous organisations regarding human rights abuses in Chile. As a result of this, Manuel Contreras, Director of DINA, threatened Cardinal Silva Henriquez that his safety could be at risk if the Church continued to interfere which in turn resulted in death threats and intimidation from agents of the regime.[30]

A key provision of the new constitution of 1980 aimed at eliminating leftist factions, “outlawed the propagation of doctrines that attack the family or put forward a concept of society based on the class struggle”. Pinochet maintained strict command over the armed forces and could depend on them to help him censor the media, arrest opposition leaders and repress demonstrations. This was accompanied by a complete shutting down of civil society with curfews, prohibition of public assembly, press blackouts, draconian censorship and university purges.[31]

.jpg/440px-Agrupación_de_Familiares_de_Detenidos_Desaparecidos_de_Chile_(de_Kena_Lorenzini).jpg)

The military rule was characterized by systematic suppression of all political dissidence. Scholars later described this as a "politicide" (or "political genocide").[32] Steve J. Stern spoke of a politicide to describe "a systematic project to destroy an entire way of doing and understanding politics and governance".[33]

Estimates of figures for victims of state violence vary. Rudolph Rummel cited early figures of up to 30,000 people killed.[34] However, these high estimates have not held to later scrutiny.

In 1996, human rights activists announced they had presented another 899 cases of people who had disappeared or been killed during the dictatorship, taking the total of known victims to 3,197, of whom 2,095 were reported killed and 1,102 missing.[35] Following the return to democracy with the Concertacion government, the Rettig Commission, a multipartisan effort by the Aylwin administration to discover the truth about the human-rights violations, listed a number of torture and detention centers (such as Colonia Dignidad, the ship Esmeralda or Víctor Jara Stadium), and found that at least 3,200 people were killed or disappeared by the regime. Later, the 2004 Valech Report confirmed the figure of 3,200 deaths but reduced the estimated number of disappearances. It tells of some 28,000 arrests in which the majority of those detained were incarcerated and in a great many cases tortured.[36] In 2011, the Chilean government officially recognized 36,948 survivors of torture and political imprisonment, as well as 3,095 people killed or disappeared at the hands of the military government.[37]

The worst violence occurred within the first three months of the coup, with the number of suspected leftists killed or "disappeared" (desaparecidos) reaching several thousand.[38] In the days immediately following the coup, the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs informed Henry Kissinger that the National Stadium was being used to hold 5,000 prisoners. Between the day of the coup and November 1973, as many as 40,000 political prisoners were held there[39][40] and as late as 1975, the CIA was still reporting that up to 3,811 were imprisoned there.[41] 1,850 of them were killed, another 1,300 are still missing to this day.[40] Some of the most famous cases of desaparecidos are Charles Horman, a U.S. citizen who was killed during the coup itself,[42] Chilean songwriter Víctor Jara, and the October 1973 Caravan of Death (Caravana de la Muerte) wherein at least 70 people were killed.

Leftist guerrilla groups and their sympathizers were also hit hard during the military regime. The MIR commander, Andrés Pascal Allende, has stated that the Marxist guerrillas lost 1,500–2,000 fighters that were either killed or had simply disappeared.[43] Among the people that were killed or had disappeared during the military regime were at least 663 MIR guerrillas.[44] The Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front stated that 49 FPMR guerrillas were killed, and hundreds tortured.[45]

According to the Latin American Institute on Mental Health and Human Rights, 200,000 people were affected by "extreme trauma"; this figure includes individuals executed, tortured, forcibly exiled, or having their immediate relatives put under detention.[46] 316 women have reported to having been subjected to rape by soldiers and agents of the dictatorship, however the number is believed to be much larger due to the preference of many women to avoid talking about this. Twenty pregnant women have declared to have suffered abortion due to torture.[47] In the words of Alejandra Matus detained women were doubly punished, first for being "leftists" and second for not conforming to their ideal of women usually being called "perra" (lit. "bitch").[48]

In addition to the violence experienced within Chile, many people fled from the regime, while others have been forcibly exiled, with some 30,000 Chileans being deported from the country.[49][50][51] particularly to Argentina, however, Operation Condor, which linked South American dictatorships together against political opponents, meant that even these exiles could be subject to violence.[52] Some 20,000–40,000 Chilean exiles were holders of passports stamped with the letter "L" (which stood for lista nacional), identifying them as persona non grata and had to seek permission before entering the country.[53] According to a study in Latin American Perspectives,[54] at least 200,000 Chileans (about 2% of Chile's 1973 population) were forced into exile. Additionally, hundreds of thousands left the country in the wake of the economic crises that followed the military coup during the 1970s and 1980s.[54] In 2003, an article published by the International Committee of the Fourth International claimed that "Of a population of barely 11 million, more than 4,000 were executed or 'disappeared', hundreds of thousands were detained and tortured, and almost a million fled the country".[55]

There were also internal exiles who due to a lack of resources could not escape abroad.[56] In the 1980s a few left-wing sympathisers hid in Puerto Gala and Puerto Gaviota, Patagonian fishing communities with a reputation of lawlessness. There they were joined by delinquents who feared torture or death by the authorities.[56]

Several scholars including Paul Zwier,[57] Peter Winn[58] and human rights organizations[59] have characterized the dictatorship as a police state exhibiting "repression of public liberties, the elimination of political exchange, limiting freedom of speech, abolishing the right to strike, freezing wages".[60]

Starting in the late 1970s the regime began to use a tactic of faking combats, usually known by its Spanish name: "falsos enfrentamientos".[61] This meant that dissidents who were murdered outright had their deaths reported in media as if they had occurred in a mutual exchange of gunfire. This was done with support of journalists who "reported" the supposed events; in some cases, the fake combats were also staged. The faked combat tactic ameliorated criticism of the regime implicitly putting culpability on the victim. It is thought that the killing of the MIR leader Miguel Enríquez in 1974 could be an early case of a faked combat. The faked combats reinforced the dictatorship narrative on the existence of an "internal war" which it used to justify its existence.[62] A particular fake combat event, lasting from September 8 to 9 1983, occurred when forces of the CNI lobbed grenades into a house, detonating the structure and killing the two men and a woman who were in the building. The agents would later state, with help from the Chilean press, that the people in the house had fired on them previously from their cars and had escaped to the house. The official story became that the three suspects had caused the explosion themselves by trying to burn and destroy incriminating evidence. Such actions had the effect of justifying the existence of heavily armed forces in Chile and the dictatorship's conduct against such "violent" offenders.[63]

During the 1970s, junta members Gustavo Leigh and Augusto Pinochet clashed on several occasions, dating back from the beginning of the 1973 Chilean coup d'état. Leigh criticized Pinochet for having joined the coup very late and then subsequently pretending to keep all power for himself. In December 1974, Leigh opposed the proposal to name Pinochet president of Chile. Leigh recalls from that moment that, "Pinochet was furious: he hit the board, broke the glass, injured his hand a little and bled. Then, Merino and Mendoza told me I should sign, because if not the junta would split. I signed." Leigh's primary concern was Pinochet's consolidation of the legislative and executive branches of government under the new government, in particular, Pinochet's decision to enact a plebiscite without formally alerting the other junta members.[64] Leigh, although a fervent supporter of the regime and hater of Marxist ideology, had already taken steps to separate the executive and legislative branches. Pinochet was said to have been angered by Leigh's continued founding of a structure to divide the executive and legislative branches, eventually leading to Pinochet consolidating his power and Leigh being removed from the regime.[65] Leigh tried to fight his dismissal from the military and government junta but on July 24, 1978, his office was blocked by paratroopers. In accordance with legal rights established by the junta government, its members could not be dismissed without evidence of impairment, hence Pinochet and his ally junta members had declared Leigh to be unfit.[64][66] Airforce General Fernando Matthei replaced Leigh as junta member.[67]

Another dictatorship member critical of Pinochet, Arturo Yovane, was removed from his post as minister of mining in 1974 and appointed ambassador at the new Chilean embassy in Tehran.[68]

Over time the dictatorship incorporated civilians into the government. Many of the Chicago boys joined the government, and Pinochet was largely sympathetic to them. This sympathy, scholar Peter Winn explains, was indebted to the fact that the Chicago boys were technocrats and thus fitted Pinochet's self-image of being "above politics".[69] Pinochet was impressed by their assertiveness as well as by their links to the financial world of the United States.[69]

Another group of civilians that collaborated extensively with the regime were the Gremialists, whose movement started in 1966 in the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.[70] The founder of the Gremialist movement, lawyer Jaime Guzmán, never assumed any official position in the military dictatorship but he remained one of the closest collaborators with Pinochet, playing an important ideological role. He participated in the design of important speeches of Pinochet and provided frequent political and doctrinal advice and consultancy.[71] Guzmán declared to have a "negative opinion" of National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) director Manuel Contreras. According to him this lead him into various "inconviniencies and difficulties".[72] From its side DINA identified Guzmán as an intelligent and manipulative actor in a secret 1976 memorandum.[73] The same document posits Guzmán manipulated Pinochet and sought ultimately to displace him from power, to lead himself a government in collaboration with Jorge Alessandri.[73] DINA spied on Guzmán and kept watch on his everyday activities.[73] According to Oscar Contardo Guzmán was identified as gay within a portfolio held by the DINA.[74]

According to scholar Carlos Huneeus, the Gremialists and the Chicago Boys shared a long-term power strategy and were linked to each other in many ways.[70]In Chile it has been very hard for the outside world to fully understand the role that everyday civilians played in keeping Pinochet's government afloat, partly because there has been scant research into the topic and partly because those who did help the regime from 1973 to 1990 have been unwilling to explore their own part. One of the exemptions is a Univision interview with Osvaldo Romo Mena, a civilian torturer in 1995 recounting his actions. Osvaldo Romo died while incarcerated for the murder of three political opponents. For the most part, civilian collaborators with Pinochet have not broken the code of silence held by the military of the 1970s to 1990s.[75]

Establishing a new constitution was a core issue for the dictatorship since it provided a mean of legitimization.[4] For this purpose the junta selected notable civilians willing to join the draft commission. Dissidents to the dictatorship were not represented in the commission.[76]

Chile's new constitution was approved in a national plebiscite held on September 11, 1980. The constitution was approved by 67% of voters under a process which has been described as "highly irregular and undemocratic",[77] and was neither free nor fair.[78] Critics of the 1980 Constitution argue that the constitution was created not to build a democracy, but to consolidate power within the central government while limiting the amount of sovereignty allowed to the people with little political presence.[78] The constitution came into force on March 11, 1981.

In 1985, due to the Caso Degollados scandal ("case of the slit throats"), General César Mendoza resigned and was replaced by General Rodolfo Stange.[67]

One of the first measures of the dictatorship was to set up a Secretaría Nacional de la Juventud (SNJ, National Youth Office). This was done on October 28, 1973, even before the Declaration of Principles of the junta made in March 1974. This was a way of mobilizing sympathetic elements of the civil society in support for the dictatorship. SNJ was created by advice of Jaime Guzmán, being an example of the dictatorship adopting a Gremialist thought.[79] Some right-wing student union leaders like Andrés Allamand were skeptical to these attempts as they were moulded from above and gathered disparate figures such as Miguel Kast, Antonio Vodanovic and Jaime Guzmán. Allamand and other young right-wingers also resented the dominance of the gremialist in SNJ, considering it a closed gremialist club.[80]

From 1975 to 1980 the SNJ arranged a series of ritualized rallies in Cerro Chacarillas reminiscent of Francoist Spain. The policy towards the sympathetic youth contrasted with the murder, surveillance and forced disappearances the dissident youth faced from the regime. Most of the documents of the SNJ were reportedly destroyed by the dictatorship in 1988.[79]

In 1962 under the presidency of Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei Montalva, the women's section expanded pre-existing neighbourhood 'mothers' centres' (which initially helped women to purchase their own sewing machines) to help garner support for their social reforms amongst the poorer sections. By the end of the 1960s, there were 8,000 centres involving 400,000 members.[81] Under Allende they were reorganised under the rubric National Confederation of Mothers' Centres (Confederación Nacional de Centros de Madres, COCEMA) and leadership of his wife, Hortensia Bussi, to encourage community initiatives and implement their policies directed at women.[82]

One of the first armed groups to oppose the dictatorship was the MIR, Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria. Immediately after the coup MIR-aligned elements in Neltume, southern Chile, unsuccessfully assaulted the local Carabineros station. Subsequently, MIR conducted several operations against the Pinochet government until the late 1980s. MIR assassinated the head of the Army Intelligence school, Lieutenant Roger Vergara, with machine gun fire in the late 1970s. The MIR also executed an attack on the base of the Chilean Secret Police (Central Nacional de Informaciones, CNI), as well as several attempts on the lives of carabineros officials and a judge of the Supreme Court in Chile.[83] Throughout the beginning years of the dictatorship the MIR was low-profile, but in August 1981 the MIR successfully killed the military leader of Santiago, General Carol Urzua Ibanez. Attacks on Chilean military official increased in the early 1980s, with the MIR killing several security forces personnel on a variety of occasions through extensive use of planted bombs in police stations or machine gun use.[84]

Representing a major shift in attitudes, the CPCh founded the FPMR on 14 December 1983, to engage in a violent armed struggle against the junta.[85] Most notably the organisation attempted to assassinate Pinochet on the 7 September 1986 under 'Operation XX Century' but were unsuccessful.[86] The group also assassinated the author of the 1980 Constitution, Jaime Guzmán on 1 April 1991.[87] They continued to operate throughout the 1990s, being designated as a terrorist organisation the U.S. Department of State and MI6, until supposedly ceasing to operate in 1999.[88]

The Catholic Church, which at first expressed its gratitude to the armed forces for saving the country from the horrors of a "Marxist dictatorship" became, under the leadership of Cardinal Raúl Silva Henríquez, the most outspoken critic of the regime's social and economic policies.[citation needed]

The Catholic Church was symbolically and institutionally powerful within Chile. Domestically, it was the second most powerful institution, behind Pinochet's government. While the Church remained politically neutral, its opposition to the regime came in the form of human rights advocacy and through the social movements that it gave a platform to. It achieved this through the establishment of the Cooperative Committee for Peace in Chile (COPACHI) and Vicariate of Solidarity. COPACHI was founded by Cardinal Raul Silve Henriquez, Archbishop of Santiago, as an immediate response to the repression of the Pinochet regime. It was apolitical in a spirit of collaboration rather than conflict with the government. Pinochet developed suspicion of COPACHI, leading to its dissolution in late 1975. In response Silva founded the Vicariate in its place. Historian Hugo Fruhling's work highlights the multifaceted nature of Vicaria.[89] Through developments and education programs in the shantytown area of Santiago, the Vicaria had mobilised around 44,000 people to join campaigns by 1979. The Church published a newsletter called Solidarity published in Chile and abroad and supplied the public with information through radio stations. Vicaria pursued a legal strategy of defending human rights, not a political strategy to re-democratise Chile.

The Days of National Protest (Jornadas de Protesta Nacional) were days of civil demonstrations that periodically took place in Chile in the 1980s against the military junta. They were characterized by street demonstrations in the downtown avenues of the city in the mornings, strikes during the day, and barricades and clashes in the periphery of the city throughout the night. The protests were faced with increased government repression from 1984, with the biggest and last protest summoned in July 1986. The protests changed the mentality of many Chileans, strengthening opposition organizations and movements in the 1988 plebiscite.

After the military took over the government in 1973, a period of dramatic economic changes began. The Chilean economy was still faltering in the months following the coup. As the military junta itself was not particularly skilled in remedying the persistent economic difficulties, it appointed a group of Chilean economists who had been educated in the United States at the University of Chicago. Given financial and ideological support from Pinochet, the U.S., and international financial institutions, the Chicago Boys advocated laissez-faire, free-market, neoliberal, and fiscally conservative policies, in stark contrast to the extensive nationalization and centrally planned economic programs supported by Allende.[90] Chile was drastically transformed from an economy isolated from the rest of the world, with strong government intervention, into a liberalized, world-integrated economy, where market forces were left free to guide most of the economy's decisions.[90]

From an economic point of view, the era can be divided into two periods. The first, from 1975 to 1982, corresponds to the period when most of the reforms were implemented. The period ended with the international debt crisis and the collapse of the Chilean economy. At that point, unemployment was extremely high, above 20 percent, and a large proportion of the banking sector had become bankrupt. The following period was characterized by new reforms and economic recovery. Some economists argue that the recovery was due to an about-face turnaround of Pinochet's free market policy, since he nationalized many of the same industries that were nationalized under Allende and fired the Chicago Boys from their government posts.[91]

Chile's main industry, copper mining, remained in government hands, with the 1980 Constitution declaring them "inalienable",[92] but new mineral deposits were open to private investment.[92] Capitalist involvement was increased, the Chilean pension system and healthcare were privatized, and Superior Education was also placed in private hands. One of the junta's economic moves was fixing the exchange rate in the early 1980s, leading to a boom in imports and a collapse of domestic industrial production; this together with a world recession caused a serious economic crisis in 1982, where GDP plummeted by 14%, and unemployment reached 33%. At the same time, a series of massive protests were organized, trying to cause the fall of the regime, which were efficiently repressed.

In 1982-1983 Chile witnessed a severe economic crisis with a surge in unemployment and a meltdown of the financial sector.[93] 16 out of 50 financial institutions faced bankruptcy.[94] In 1982 the two biggest banks were nationalized to prevent an even worse credit crunch. In 1983 another five banks were nationalized and two banks had to be put under government supervision.[95] The central bank took over foreign debts. Critics ridiculed the economic policy of the Chicago Boys as "Chicago way to socialism".[96]

After the economic crisis, Hernán Büchi became Minister of Finance from 1985 to 1989, introducing a return to a free market economic policy. He allowed the peso to float and reinstated restrictions on the movement of capital in and out of the country. He deleted some bank regulations and simplified and reduced the corporate tax. Chile went ahead with privatizations, including public utilities and the re-privatization of companies that had briefly returned to government control during the 1982–83 crisis. From 1984 to 1990, Chile's gross domestic product grew by an annual average of 5.9%, the fastest on the continent. Chile developed a good export economy, including the export of fruits and vegetables to the northern hemisphere when they were out of season, and commanded high export prices.

Initially the economic reforms were internationally praised. Milton Friedman wrote in his Newsweek column on 25 January 1982 about the Miracle of Chile. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher credited Pinochet with bringing about a thriving, free-enterprise economy, while at the same time downplaying the junta's human rights record, condemning an "organised international Left who are bent on revenge".

With the economic crises of 1982 the "monetarist experiment" was regarded by critics a failure.[97]

The pragmatic economic policy after the crises of 1982 is appreciated for bringing constant economic growth.[98] It is questionable whether the radical reforms of the Chicago Boys contributed to post-1983 growth.[99] According to Ricardo Ffrench-Davis, economist and consultant of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, the 1982 crises as well as the success of the pragmatic economic policy after 1982 proves that the 1975–1981 radical economic policy of the Chicago Boys actually harmed the Chilean economy.[100]

The economic policies espoused by the Chicago Boys and implemented by the junta initially caused several economic indicators to decline for Chile's lower classes.[101] Between 1970 and 1989, there were large cuts to incomes and social services. Wages decreased by 8%.[102] Family allowances in 1989 were 28% of what they had been in 1970 and the budgets for education, health and housing had dropped by over 20% on average.[102][103] The massive increases in military spending and cuts in funding to public services coincided with falling wages and steady rises in unemployment, which averaged 26% during the worldwide economic slump of 1982–85[102] and eventually peaked at 30%.

In 1990, the LOCE act on education initiated the dismantlement of public education.[92] According to Communist Party of Chile member and economist Manuel Riesco Larraín:

Overall, the impact of neoliberal policies has reduced the total proportion of students in both public and private institutions in relation to the entire population, from 30 per cent in 1974 down to 25 per cent in 1990, and up only to 27 per cent today. If falling birth rates have made it possible today to attain full coverage at primary and secondary levels, the country has fallen seriously behind at tertiary level, where coverage, although now growing, is still only 32 per cent of the age group. The figure was twice as much in neighbouring Argentina and Uruguay, and even higher in developed countries—South Korea attaining a record 98 per cent coverage. Significantly, tertiary education for the upper-income fifth of the Chilean population, many of whom study in the new private universities, also reaches above 70 per cent.[92]

The junta relied on the middle class, the oligarchy, domestic business, foreign corporations, and foreign loans to maintain itself.[104] Under Pinochet, funding of military and internal defence spending rose 120% from 1974 to 1979.[105] Due to the reduction in public spending, tens of thousands of employees were fired from other state-sector jobs.[105] The oligarchy recovered most of its lost industrial and agricultural holdings, for the junta sold to private buyers most of the industries expropriated by Allende's Popular Unity government.

Financial conglomerates became major beneficiaries of the liberalized economy and the flood of foreign bank loans. Large foreign banks reinstated the credit cycle, as the Junta saw that the basic state obligations, such as resuming payment of principal and interest installments, were honored. International lending organizations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Inter-American Development Bank lent vast sums anew.[102]Many foreign multinational corporations such as International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT), Dow Chemical, and Firestone, all expropriated by Allende, returned to Chile.[102]

Having risen to power on an anti-Marxist agenda, Pinochet found common cause with the military dictatorships of Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and later, Argentina. The six countries eventually formulated a plan known as Operation Condor, in which the security forces of participating states would target active left-wing militants, guerrilla fighters, and their alleged sympathizers in the allied countries.[106] Pinochet's government received tacit approval and material support from the United States. The exact nature and extent of this support is disputed. (See U.S. role in 1973 Coup, U.S. intervention in Chile and Operation Condor for more details.) It is known, however, that the American Secretary of State at the time, Henry Kissinger, practiced a policy of supporting coups in nations which the United States viewed as leaning toward Communism.[107]

The new junta quickly broke diplomatic relations with Cuba and North Korea, which had been established under the Allende government. Shortly after the junta came to power, several communist countries, including the Soviet Union, North Vietnam, East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia, severed diplomatic relations with Chile however, Romania and the People's Republic of China both continued to maintain diplomatic relations with Chile.[108] Pinochet nurtured the relationship with China.[109][110] The government broke diplomatic relations with Cambodia in January 1974[111] and with South Vietnam in March 1974.[112] Pinochet attended the funeral of General Francisco Franco, dictator of Spain from 1936 to 1975, in late 1975.

In 1980, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos had invited the entire Junta (consisting at this point of Pinochet, Merino, Matthei, and Mendoza) to visit the country as part of a planned tour of Southeast Asia in an attempt to help improve their image and bolster military and economic relations with the Philippines, Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong. Due to intense U.S. pressure at the last minute (while Pinochet's plane was halfway en route over the Pacific), Marcos cancelled the visit and denied Pinochet landing rights in the country. Pinochet and the junta were further caught off guard and humiliated when they were forced to land in Fiji to refuel for the planned return to Santiago, only to be met with airport staff who refused to assist the plane in any way (the Fijian military was called in instead), invasive and prolonged customs searches, exorbitant fuel and aviation service charges, and hundreds of angry protesters who pelted his plane with eggs and tomatoes. The usually stoic and calm Pinochet became enraged, firing his Foreign Minister Hernán Cubillos, several diplomats, and expelling the Philippine Ambassador.[113][114] Relations between the two countries were restored only in 1986 when Corazon Aquino assumed the presidency of the Philippines after Marcos was ousted in a non-violent revolution, the People Power Revolution.

President of Argentina Juan Perón condemned the 1973 coup as a "fatality for the continent" stating that Pinochet represented interests "well known" to him. He praised Allende for his "valiant attitude" and took note of the role of the United States in instigating the coup by recalling his familiarity with coup-making processes.[115] On 14 May 1974 Perón received Pinochet at the Morón Airbase. Pinochet was heading to meet Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay so the encounter at Argentina was technically a stopover. Pinochet and Perón are both reported to have felt uncomfortable during the meeting. Perón expressed his wishes to settle the Beagle conflict and Pinochet his concerns about Chilean exiles in Argentina near the frontier with Chile. Perón would have conceded on moving these exiles from the frontiers to eastern Argentina, but he warned "Perón takes his time, but accomplishes" (Perón tarda, pero cumple). Perón justified his meeting with Pinochet stating that it was important to keep good relations with Chile under all circumstances and with whoever might be in government.[115] Perón died in July 1974 and was succeeded by his wife, Isabel Perón, who was overthrown in 1976 by the Argentine military who installed themselves as a new dictatorship in Argentina.

Chile was on the brink of being invaded by Argentina, as the Argentina junta initiated Operation Soberanía on 22 December 1978 because of the strategic Picton, Lennox and Nueva islands at the southern tip of South America on the Beagle Channel. A full-scale war was prevented only by the calling off of the operation by Argentina for military and political reasons.[116] But the relations remained tense as Argentina invaded the Falklands (Operation Rosario). Chile along with Colombia, were the only countries in South America to criticize the use of force by Argentina in its war with the UK over the Falkland Islands. Chile actually helped the United Kingdom during the war. The two countries (Chile and Argentina) finally agreed to papal mediation over the Beagle Channel that finally ended in the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984 between Chile and Argentina (Tratado de Paz y Amistad). Chilean sovereignty over the islands and Argentinian east of the surrounding sea is now undisputed.

.jpg/440px-Orlando_Letelier,_Washingron_DC,_1976_(de_Marcelo_Montecino).jpg)

The U.S. government had been interfering in Chilean politics since 1961, and it spent millions trying to prevent Allende from coming to power, and subsequently undermined his presidency through financing opposition. Declassified Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) documents reveal U.S. knowledge and alleged involvement in the coup.[117] They provided material support to the military regime after the coup, although criticizing it in public. A document released by the CIA in 2000, titled "CIA Activities in Chile", revealed that the CIA actively supported the military junta during and after the overthrow of Allende and that it made many of Pinochet's officers into paid contacts of the CIA or U.S. military, even though some were known to be involved in human rights abuses.[118]The U.S. continued to give the junta substantial economic support between the years 1973–79, despite concerns from more liberal Congressmen, as seen from the results of the Church Committee. U.S. public stance did condemn the human rights violations, however declassified documents reveal such violations were not an obstacle for members of the Nixon and Ford administrations. Henry Kissinger visited Santiago in 1976 for the annual conference of the Organisation of American States. During his visit he privately met with Pinochet and reassured the leader of internal support from the U.S. administration.[119]The U.S. went beyond verbal condemnation in 1976, after the murder of Orlando Letelier in Washington D.C., when it placed an embargo on arms sales to Chile that remained in effect until the restoration of democracy in 1989. This more aggressive stance coincided with the election of Jimmy Carter who shifted the focus of U.S. foreign policy towards human rights.

The U.S. arms embargo served to kickstart the Chilean weapons industry, with the military aviation company ENAER standing out as the military manufacturer that developed the most following the embargo.[120] On the contrary, the naval manufacturer ASMAR was the least impacted by the embargo.[120]

Britain's initial reaction to the overthrowing of Allende was one of caution. The Conservative government recognised the legitimacy of the new government but didn't offer any other declarations of support.[121]

Under the Labour government of 1974–1979, while Britain regularly condemned the junta at the United Nations for its human rights abuses, bilateral relations between the two were not affected to the same degree.[122] Britain formally withdrew its Santiago ambassador in 1974, however reinstated the position in 1980 under the Margaret Thatcher government.[123]

Chile was neutral during the Falkland War, but its Westinghouse long-range radar deployed at Punta Arenas, in southern Chile, gave the British task force early warning of Argentinian air attacks, which allowed British ships and troops in the war zone to take defensive action.[124] Margaret Thatcher said that the day the radar was taken out of service for overdue maintenance was the day Argentinian fighter-bombers bombed the troopships Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram, leaving approximately 50 dead and 150 wounded.[125] According to Chilean Junta and former Air Force commander Fernando Matthei, Chilean support included military intelligence gathering, radar surveillance, British aircraft operating with Chilean colours and the safe return of British special forces, among other things.[126] In April and May 1982, a squadron of mothballed RAF Hawker Hunter fighter bombers departed for Chile, arriving on 22 May and allowing the Chilean Air Force to reform the No. 9 "Las Panteras Negras" Squadron. A further consignment of three frontier surveillance and shipping reconnaissance Canberras left for Chile in October. Some authors suggest that Argentina might have won the war had she been allowed to employ the VIth and VIIIth Mountain Brigades, which remained guarding the Andes mountain chain.[127] Pinochet subsequently visited Margaret Thatcher for tea on more than one occasion.[128] Pinochet's controversial relationship with Thatcher led Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair to mock Thatcher's Conservatives as "the party of Pinochet" in 1999.

Although France received many Chilean political refugees, it also secretly collaborated with Pinochet. French journalist Marie-Monique Robin has shown how Valéry Giscard d'Estaing's government secretly collaborated with Videla's junta in Argentina and with Pinochet's regime in Chile.[129]

Green deputies Noël Mamère, Martine Billard and Yves Cochet on September 10, 2003, requested a Parliamentary Commission on the "role of France in the support of military regimes in Latin America from 1973 to 1984" before the Foreign Affairs Commission of the National Assembly, presided by Edouard Balladur. Apart from Le Monde, newspapers remained silent about this request.[130] However, deputy Roland Blum, in charge of the commission, refused to hear Marie-Monique Robin, and published in December 2003 a 12 pages report qualified by Robin as the summum of bad faith. It claimed that no agreement had been signed, despite the agreement found by Robin in the Quai d'Orsay.[131][132]

When then Minister of Foreign Affairs Dominique de Villepin traveled to Chile in February 2004, he claimed that no cooperation between France and the military regimes had occurred.[133]

Reportedly one of Juan Velasco Alvarado's main goals was to militarily reconquer the lands lost by Peru to Chile in the War of the Pacific.[134] It is estimated that from 1970 to 1975 Peru spent up to US$2 Billion (roughly US$20 Billion in 2010's valuation) on Soviet armament.[135] According to various sources Velasco's government bought between 600 and 1200 T-55 Main Battle Tanks, APCs, 60 to 90 Sukhoi 22 warplanes, 500,000 assault rifles, and even considered the purchase of the British Centaur-class light fleet carrier HMS Bulwark.[135]

The enormous amount of weaponry purchased by Peru caused a meeting between former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Pinochet in 1976.[135] Velasco's military plan was to launch a massive sea, air, and land invasion against Chile.[135] In 1999, Pinochet claimed that if Peru had attacked Chile during 1973 or even 1978, Peruvian forces could have penetrated deep south into Chilean territory, possibly military taking the Chilean city of Copiapó located halfway to Santiago.[134] The Chilean Armed Forces considered launching a preventive war to defend itself. Though, Pinochet's Chilean Air Force General Fernando Matthei opposed a preventive war and responded that "I can guarantee that the Peruvians would destroy the Chilean Air Force in the first five minutes of the war".[134] Some analysts believe the fear of attack by Chilean and US officials as largely unjustified but logical for them to experience, considering the Pinochet dictatorship had come into power with a coup against democratically elected president Salvador Allende. According to sources, the alleged invasion scheme could be seen from the Chilean's government perspective as a plan for some kind of leftist counterattack.[136] While acknowledging the Peruvian plans were revisionistic scholar Kalevi J. Holsti claim more important issues were behind the "ideological incompatibility" between the regimes of Velasco Alvarado and Pinochet and that Peru would have been concerned about Pinochet's geopolitical views on Chile's need of naval hegemony in the Southeastern Pacific.[137]

Chileans should stop with the bullshit or tomorrow I shall eat breakfast in Santiago.

Francoist Spain had enjoyed warm relations with Chile while Allende was in power.[139][140] Pinochet admired and was very much influenced by Francisco Franco, but Franco's successors had a cold attitude towards Pinochet as they did not want to be linked to him.[139][140] When Pinochet traveled to the funeral of Francisco Franco in 1975, the President of France Valéry Giscard d'Estaing pressured the Spanish government to refuse Pinochet to be at the crowning of Juan Carlos I of Spain by letting Spanish authorities know that Giscard would not be there if Pinochet was present. Juan Carlos I personally called Pinochet to let him know he was not welcome at his crowning.[141]

While in Spain Pinochet is reported to have met with Stefano Delle Chiaie in order to plan the killing of Carlos Altamirano, the Secretary General of the Socialist Party of Chile.[142]

The previous drop in foreign aid during the Allende years was immediately reversed following Pinochet's ascension; Chile received US$322.8 million in loans and credits in the year following the coup.[143] There was considerable international condemnation of the military regime's human rights record, a matter that the United States expressed concern over as well after Orlando Letelier's 1976 assassination in Washington DC.(Kennedy Amendment, later International Security Assistance and Arms Export Control Act of 1976).

After the Chilean military coup in 1973, Fidel Castro promised Chilean revolutionaries' far-reaching aid. Initially Cuban support for resistance consisted of clandestine distribution of funds to Chile, human rights campaigns at the UN to isolate the Chilean dictatorship, and efforts to undermine US-Chilean bilateral relations. Eventually Cuba's policy changed to arming and training insurgents. Once their training was completed, Cuba helped the guerrillas return to Chile, providing false passports and false identification documents.[144] Cuba's official newspaper, Granma, boasted in February 1981 that the "Chilean Resistance" had successfully conducted more than 100 "armed actions" throughout Chile in 1980. By late 1980, at least 100 highly trained MIR guerrillas had reentered Chile and the MIR began building a base for future guerrilla operations in Neltume, a mountainous forest region in southern Chile. In a massive operation spearheaded by Chilean Army Para-Commandos, security forces involving some 2,000 troops, were forced to deploy in the Neltume mountains from June to November 1981, where they destroyed two MIR bases, seizing large caches of munitions and killing a number of MIR commandos. In 1986, Chilean security forces discovered 80 tons of munitions, including more than three thousand M-16 rifles and more than two million rounds of ammunition, at the tiny fishing harbor of Carrizal Bajo, smuggled ashore from Cuban fishing trawlers off the coast of Chile.[145] The operation was overseen by Cuban naval intelligence, and also involved the Soviet Union. Cuban Special Forces had also instructed the FPMR guerrillas that ambushed Augusto Pinochet's motorcade on 8 September 1986, killing five bodyguards and wounding 10.[146]

Influenced by Antonio Gramsci's work on cultural hegemony, proposing that the ruling class can maintain power by controlling cultural institutions, Pinochet clamped down on cultural dissidence.[147] This brought Chilean cultural life into what sociologist Soledad Bianchi has called a "cultural blackout".[148] The government censored non-sympathetic individuals while taking control of mass media.[148]

The military dictatorship sought to isolate Chilean radio listeners from the outside world by changing radio frequencies to middle wavelengths.[149] This together with the shutdown of radio stations sympathetic to the former Allende administration impacted music in Chile.[149] The music catalog was censored with the aid of listas negras (blacklists) but little is known on how these were composed and updated.[150] The formerly thriving Nueva canción scene suffered from the exile or imprisonment of many bands and individuals.[148] A key musician, Víctor Jara, was tortured and killed by elements of the military.[148] According to Eduardo Carrasco of Quilapayún in the first week after the coup, the military organized a meeting with folk musicians where they announced that the traditional instruments charango and quena were banned.[148] The curfew imposed by the dictatorship forced the remaining Nueva Canción scene, now rebranded as Canto Nuevo, into "semiclandestine peñas, while alternative groove disseminated in juvenile fiestas".[151] A scarcity of records and the censorship imposed on part of the music catalog made a "cassette culture" emmerge among the affected audiences.[151] The proliferation of pirate cassettes was enabled by tape recorders,[150] and in some cases this activity turned commercial as evidenced by the pirate cassette brand Cumbre y Cuatro.[149] The music of Silvio Rodríguez became first known in Chile this way.[150] Cassettes aside, some music enthusiasts were able to supply themselves with rare or suppressed records with help of relatives in exile abroad.[149]

The dictatorship controlled the Viña del Mar International Song Festival and used it promote sympathetic artists, in particular those that were part of the Acto de Chacarillas in 1977.[152] In the first years of dictatorship Pinochet was a common guest at the festival.[153] Pinochet's advisor Jaime Guzmán was also spotted on occasion at the festival.[153] Festival presenter Antonio Vodanovic publicly praised the dictator and his wife Lucia Hiriart on one occasion on behalf of "the Chilean youth".[153] Supporters of the dictatorship appropriated the song Libre of Nino Bravo, and this song was performed by Edmundo Arrocet in the first post-coup edition while Pinochet was present in the public.[154][155] From 1980 onward when the festival begun to be aired internationally the regime used it to promote a favourable image of Chile abroad.[152] For that purpose in 1980 the festival spent a big budget on bringing popular foreign artist including Miguel Bosé, Julio Iglesias and Camilo Sesto.[152] The folk music contest of the Viña del Mar International Song Festival had become increasingly politicized during the Allende years and was suspended by organizers from the time of coup until 1980.[152]

Elements of military distrusted Mexican music which was widespread in the rural areas of south-central Chile.[149] There are testimonies of militaries calling Mexican music "communist".[149] Militaries dislike of Mexican music may be linked to the Allende administration's close links with Mexico, the "Mexican revolutionary discourse" and the over-all low prestige of Mexican music in Chile.[149] The dictatorship, however, didn’t suppress Mexican music as a whole but distinguished different strands, some of which were actually promoted.[149]

Cueca and Mexican music coexisted with similar levels of popularity in the Chilean countryside in the 1970s.[156][149] Being distinctly Chilean the cueca was selected by the military dictatorship as a music to be promoted.[149] The cueca was named the national dance of Chile due to its substantial presence throughout the history of the country and announced as such through a public decree in the Official Journal (Diario Oficial) on November 6, 1979.[157] Cueca specialist Emilio Ignacio Santana argues that the dictatorship's appropriation and promotion of cueca harmed the genre.[149] The dictatorship's endorsement of the genre meant according to Santana that the rich landlord huaso became the icon of the cueca and not the rural labourer.[149]

The 1980s saw an invasion of Argentine rock bands into Chile. These included Charly García, the Enanitos Verdes, G.I.T. and Soda Stereo among others.[158]

Contemporary Chilean rock group Los Prisioneros complained against the ease with which Argentine Soda Stereo made appearances on Chilean TV or in Chilean magazines and the ease they could obtain musical equipment for concerts in Chile.[159] Soda Stereo was invited to Viña del Mar International Song Festival while Los Prisioneros were ignored despite their popular status.[160] This situation was because Los Prisioneros were censored by media under the influence of the military dictatorship.[159][160] Los Prisioneros' marginalization by the media was further aggravated by their call to vote against the dictatorship on the plebiscite of 1988.[160]

For Chile to become once again the land of poets, and not the land of murderers!

—Sol y Lluvia[161]

Experimental theatre groups from Universidad de Chile and Pontifical Catholic University of Chile were restricted by the military regime to performing only theatre classics.[162] Some established groups like Grupo Ictus were tolerated while new formations like Grupo Aleph were repressed. This last group had its members jailed and forced into exile after performing a parody on the 1973 Chilean coup d'état.[162] In the 1980s a grassroots street theatre movement emerged.[162]

The dictatorship promoted the figure of Nobel laureate Gabriela Mistral who was presented as a symbol of "summission to the authority" and "social order".[163]

Following the approval of the 1980 Constitution, a plebiscite was scheduled for October 5, 1988, to vote on a new eight-year presidential term for Pinochet.

The Constitution, which took effect on 11 March 1981, established a "transition period," during which Pinochet would continue to exercise executive power and the junta's legislative power, for the next eight years. Before that period ended, a candidate for president was to be proposed by the Commanders-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and Carabinero Chief General for the following period of eight years. The candidate then was to be ratified by registered voters in a national plebiscite. On 30 August 1988 Pinochet was declared to be the candidate.[164]

The Constitutional Court of Chile ruled that the plebiscite should be carried out as stipulated by Article 64 in the Constitution. That included a programming slot in television (franja electoral) during which all positions, in this case, two, Sí (yes), and No, would have two free slots of equal and uninterrupted TV time, simultaneously broadcast by all TV channels, with no political advertising outside those spots. The allotment was scheduled in two off-prime time slots: one before the afternoon news and the other before the late-night news, from 22:45 to 23:15 each night (the evening news was from 20:30 to 21:30, and primetime from 21:30 to 22:30). The opposition No campaign, headed by Ricardo Lagos, produced colorful, upbeat programs, telling the Chilean people to vote against the extension of the presidential term. Lagos, in a TV interview, pointed his index finger towards the camera and directly called on Pinochet to account for all the "disappeared" persons. The Sí campaign did not argue for the advantages of extension, but was instead negative, claiming that voting "no" was equivalent to voting for a return to the chaos of the UP government.

Pinochet lost the 1988 referendum, where 56% of the votes rejected the extension of the presidential term, against 44% for "Sí", and, following the constitutional provisions, he stayed as president for one more year. The presidential election was held in December 1989, at the same time as congressional elections that were due to take place. Pinochet left the presidency on March 11, 1990, and transferred power to his political opponent Patricio Aylwin, the new democratically elected president. Due to the same transitional provisions of the constitution, Pinochet remained as Commander-in-Chief of the Army, until March 1998.

From the 1989 elections onwards, the military had officially left the political sphere in Chile. Pinochet did not endorse any candidate publicly. Former Pinochet economic minister Hernán Büchi ran for president as the candidate of the two right-wing parties RN and UDI. He had little political experience and was relatively young and credited with Chile's good economic performance in the second half of the 1980s. The right-wing parties faced several problems in the elections: there was considerable infighting between RN and UDI, Büchi had only very reluctantly accepted to run for president and right-wing politicians struggled to define their position towards the Pinochet regime. In addition to this right-wing populist Francisco Javier Errázuriz Talavera ran independently for president and made several election promises Büchi could not match.[4]

The centre-left coalition Concertación was more united and coherent. Its candidate Patricio Aylwin, a Christian Democrat, behaved as if he had won and refused a second television debate with Büchi. Büchi attacked Aylwin on a remark he had made concerning that inflation rate of 20% was not much and he also accused Aylwin of making secret agreements with the Communist Party of Chile, a party that was not part of Concertación.[4] Aylwin spoke with authority about the need to clarify human rights violations but did not confront the dictatorship for it; in contrast, Büchi, as a former regime minister, lacked any credibility when dealing with human right violations.[4]

Büchi and Errázuriz lost to Patricio Aylwin in the election. The electoral system meant that the largely Pinochet-sympathetic right was overrepresented in parliament in such a way that it could block any reform to the constitution. This over-representation was crucial for UDI in obtaining places in parliament and securing its political future. The far-left and the far-right performed poorly in the election.[4]

Following the restoration of Chilean democracy and the successive administrations that followed Pinochet, the Chilean economy has increasingly prospered. Unemployment stands at 7% as of 2007, with poverty estimated at 18.2% for the same year, both relatively low for the region.[165] However, in 2019 the Chilean government faced public scrutiny for its economic policies. In particular, for the long-term effects of Pinochet's neoliberal policies.[166] Mass protests broke out throughout Santiago, due to increasing prices of the metro ticket.[167] For many Chileans this highlighted the disproportionate distribution of wealth amongst Chile.

The "Chilean Variation" has been seen as a potential model for nations that fail to achieve significant economic growth.[168] The latest is Russia, for whom David Christian warned in 1991 that "dictatorial government presiding over a transition to capitalism seems one of the more plausible scenarios, even if it does so at a high cost in human rights violations".[169]

A survey published by pollster CERC on the eve of the 40th anniversary commemorations of the coup gave some idea of how Chileans perceived the dictatorship. According to the poll, 55% of Chileans regarded the 17 years of dictatorship as either bad or very bad, while 9% said they were good or very good.[170] In 2013, the newspaper El Mercurio asked Chileans if the state had done enough to compensate victims of the dictatorship for the atrocities they suffered; 30% said yes, 36% said no, and the rest were undecided.[171] In order to keep the memories of the victims and the disappeared alive, memorial sites have been constructed throughout Chile, as a symbol of the country's past. Some notable examples include Villa Grimaldi, Londres 38, Paine Memorial and the Museum of Memory and Human Rights.[172] These memorials were built by family members of the victims, the government and ex-prisoners of the dictatorship. These have become popular tourist destinations and have provided a visual narrative of the atrocities of the dictatorship. These memorials have aided in Chile's reconciliation process, however, there is still debate amongst Chile as to whether these memorials do enough to bring the country together.

The relative economic success of the Pinochet dictatorship has brought about some political support for the former dictatorship. In 1998, then-Brazilian congressman and retired military officer Jair Bolsonaro praised Pinochet, saying his regime "should have killed more people".[173]

Every year on the anniversary of the coup protests can be seen throughout the country.[174]

The indictment and arrest of Pinochet occurred on 10 October 1998 in London. He returned to Chile in March 2000 but was not charged with the crimes against him. On his 91st birthday on 25 November 2006, in a public statement to supporters, Pinochet for the first time claimed to accept "political responsibility" for what happened in Chile under his regime, though he still defended the 1973 coup against Salvador Allende. In a statement read by his wife Lucia Hiriart, he said, Today, near the end of my days, I want to say that I harbour no rancour against anybody, that I love my fatherland above all. ... I take political responsibility for everything that was done.[175]

La fuerte posición de los militares en ellas, junto a la continuación de turbulencias [...] emanadas de actos de rebeldía y abierto desafío a las nuevas autoridades por parte de jefes castrenses, pusieron también en el tapete los temas del control civil o poder democrático sobre dicha institución y sus dificultades [...]. Desde esta situación se puso también a Chile en un debate comparado sobre los problemas en la implantación de la supremacía o control civil, sus contextos institucionales y sus mecanismos más efectivos...

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2024 (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)