Дефицит воды (тесно связанный с водным стрессом или водным кризисом ) — это нехватка ресурсов пресной воды для удовлетворения стандартного спроса на воду. Существует два типа дефицита воды. Один из них — физический. Другой — экономический дефицит воды . [2] : 560 Физический дефицит воды — это когда воды недостаточно для удовлетворения всех потребностей. Это включает воду, необходимую для функционирования экосистем . Регионы с пустынным климатом часто сталкиваются с физическим дефицитом воды. [3] Центральная Азия , Западная Азия и Северная Африка являются примерами засушливых территорий. Экономический дефицит воды является результатом отсутствия инвестиций в инфраструктуру или технологии для забора воды из рек, водоносных горизонтов или других источников воды. Он также является результатом слабых человеческих возможностей для удовлетворения спроса на воду. [2] : 560 Многие люди в странах Африки к югу от Сахары живут с экономическим дефицитом воды. [4] : 11

В мире достаточно пресной воды, в среднем за год, чтобы удовлетворить спрос. Таким образом, дефицит воды вызван несоответствием между тем, когда и где людям нужна вода, и тем, когда и где она доступна. [5] Одной из основных причин увеличения мирового спроса на воду является рост числа людей . Другими причинами являются улучшение условий жизни, изменение рациона питания (в сторону большего количества продуктов животного происхождения) [6] и расширение орошаемого земледелия . [7] [8] Изменение климата (включая засухи или наводнения ), вырубка лесов , загрязнение воды и расточительное использование воды также могут означать, что воды недостаточно. [9] Эти изменения в дефиците также могут быть функцией преобладающей экономической политики и подходов к планированию.

Оценки дефицита воды рассматривают множество типов информации. Они включают зеленую воду ( влажность почвы ), качество воды , требования к экологическому потоку и виртуальную торговлю водой . [6] Водный стресс является одним из параметров для измерения дефицита воды. Он полезен в контексте Цели устойчивого развития 6. [ 10] Полмиллиарда человек живут в районах с острой нехваткой воды в течение всего года, [5] [6] и около четырех миллиардов человек сталкиваются с острой нехваткой воды по крайней мере один месяц в году. [5] [11] Половина крупнейших городов мира испытывают нехватку воды. [11] 2,3 миллиарда человек проживают в странах с нехваткой воды (что означает менее 1700 м 3 воды на человека в год). [12] [13] [14]

Существуют различные способы сокращения дефицита воды. Это можно сделать посредством управления спросом и предложением, сотрудничества между странами и сохранения водных ресурсов . Расширение источников пригодной для использования воды может помочь. Повторное использование сточных вод и опреснение — это способы сделать это. Другие сокращают загрязнение воды и вносят изменения в торговлю виртуальной водой.

Дефицит воды определяется как « объемное изобилие или недостаток пресноводных ресурсов », и считается, что он «вызван человеком». [15] : 4 Это также можно назвать «физическим дефицитом воды». [4] Существует два типа дефицита воды. Один из них — физический дефицит воды , а другой — экономический дефицит воды . [2] : 560 Некоторые определения дефицита воды рассматривают потребности окружающей среды в воде. Этот подход различается в разных организациях. [15] : 4

В научной литературе существует несколько определений. Они охватывают термины «дефицит воды», «водный стресс» и «водный риск». Водный мандат генерального директора, инициатива Глобального договора ООН , предложил гармонизировать их в 2014 году. [15] : 2 В своем дискуссионном документе они заявляют, что эти три термина не следует использовать взаимозаменяемо. [15] : 3

Некоторые организации определяют «водную напряженность» как более широкое понятие. Оно будет рассматривать наличие воды, качество воды и доступность. Доступность зависит от существующей инфраструктуры. Она также зависит от того, могут ли потребители позволить себе платить за воду. [15] : 4 Некоторые эксперты называют это «экономическим дефицитом воды». [4]

ФАО определяет водный стресс как «симптомы дефицита или нехватки воды». Такими симптомами могут быть «растущий конфликт между пользователями и конкуренция за воду, снижение стандартов надежности и обслуживания, неурожаи и отсутствие продовольственной безопасности». [ 17] : 6 Это измеряется с помощью ряда индексов водного стресса.

Группа ученых дала еще одно определение водного стресса в 2016 году. «Водный стресс относится к влиянию высокого потребления воды (либо забора, либо потребления) относительно доступности воды». [1] Это рассматривает водный стресс как «дефицит, обусловленный спросом».

Эксперты определили два типа дефицита воды. Один из них — физический дефицит воды. Другой — экономический дефицит воды. Эти термины были впервые определены в исследовании 2007 года, проведенном Международным институтом управления водными ресурсами . В нем рассматривалось использование воды в сельском хозяйстве за предыдущие 50 лет. Целью исследования было выяснить, достаточно ли в мире водных ресурсов для производства продовольствия для растущего населения в будущем. [4] [17] : 1

Физический дефицит воды возникает, когда природных водных ресурсов недостаточно для удовлетворения всех потребностей. Это включает воду, необходимую для нормального функционирования экосистем. Засушливые регионы часто страдают от физического дефицита воды. Влияние человека на климат усилило дефицит воды в районах, где он уже был проблемой. [18] Это также происходит там, где вода кажется обильной, но где ресурсы перераспределяются. Одним из примеров является чрезмерное развитие гидравлической инфраструктуры . Это может быть для орошения или выработки энергии . Существует несколько симптомов физического дефицита воды. Они включают в себя серьезную деградацию окружающей среды , снижение уровня грунтовых вод и распределение воды в пользу одних групп по сравнению с другими. [17] : 6

Эксперты предложили другой индикатор. Это называется экологический дефицит воды . Он учитывает количество воды, качество воды и требования к экологическому стоку. [19]

Воды не хватает в густонаселенных засушливых районах . По прогнозам, там будет менее 1000 кубических метров воды на душу населения в год. Примерами являются Центральная и Западная Азия, а также Северная Африка. [3] Исследование, проведенное в 2007 году, показало, что более 1,2 миллиарда человек живут в районах с физическим дефицитом воды. [20] Этот дефицит воды касается воды, доступной для производства продуктов питания, а не питьевой воды , объем которой гораздо меньше. [3] [21]

Некоторые ученые выступают за добавление третьего типа, который будет называться экологическим дефицитом воды. [19] Он будет фокусироваться на потребности экосистем в воде. Он будет ссылаться на минимальное количество и качество сброса воды, необходимое для поддержания устойчивых и функциональных экосистем. Некоторые публикации утверждают, что это просто часть определения физического дефицита воды. [17] [4]

.jpg/440px-Collecting_clean_water_with_the_help_of_UKaid_(5330401479).jpg)

Экономический дефицит воды возникает из-за отсутствия инвестиций в инфраструктуру или технологии для забора воды из рек, водоносных горизонтов или других источников воды. Он также отражает недостаточный человеческий потенциал для удовлетворения спроса на воду. [22] : 560 Это заставляет людей, не имеющих надежного доступа к воде, преодолевать большие расстояния, чтобы принести воду для бытовых и сельскохозяйственных нужд. Такая вода часто бывает грязной.

Программа развития ООН утверждает, что экономическая нехватка воды является наиболее распространенной причиной нехватки воды. Это происходит потому, что большинство стран или регионов имеют достаточно воды для удовлетворения бытовых, промышленных, сельскохозяйственных и экологических нужд. Но у них нет средств, чтобы обеспечить ее доступным способом. [23] Около пятой части населения мира в настоящее время проживает в регионах, страдающих от физической нехватки воды. [23]

Четверть населения мира страдает от экономической нехватки воды. Это характерно для большей части стран Африки к югу от Сахары. [4] : 11 Поэтому улучшение водной инфраструктуры там может помочь сократить бедность . Инвестиции в удержание воды и ирригационную инфраструктуру помогут увеличить производство продовольствия. Это особенно актуально для развивающихся стран, которые полагаются на низкоурожайное сельское хозяйство. [24] Предоставление воды, достаточной для потребления, также принесет пользу общественному здравоохранению. [25] Это не только вопрос новой инфраструктуры. Экономическое и политическое вмешательство необходимо для борьбы с бедностью и социальным неравенством. Отсутствие финансирования означает необходимость планирования. [26]

Обычно акцент делается на улучшении источников воды для питья и бытовых нужд. Но больше воды используется для таких целей, как купание, стирка, разведение скота и уборка, чем для питья и приготовления пищи. [25] Это говорит о том, что слишком большой акцент на питьевой воде решает только часть проблемы. Поэтому он может ограничить спектр доступных решений. [25]

Существует несколько показателей для измерения дефицита воды. Один из них — это отношение использования воды к ее доступности. Он также известен как коэффициент критичности. Другой — это индикатор IWMI. Он измеряет физический и экономический дефицит воды. Другой — это индекс водной бедности. [6]

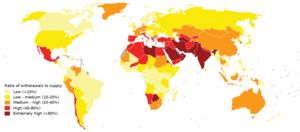

«Водный стресс» — это критерий для измерения дефицита воды. Эксперты используют его в контексте Цели устойчивого развития 6. [ 10] В отчете ФАО за 2018 год было дано определение водного стресса. Он описывается как «соотношение между общим забором пресной воды (TFWW) всеми основными секторами и общими возобновляемыми ресурсами пресной воды (TRWR) с учетом требований к экологическому стоку (EFR)». Это означает, что значение TFWW делится на разницу между TRWR минус EFR. [32] : xii Экологические стоки — это потоки воды, необходимые для поддержания пресноводных и эстуарных экосистем . Предыдущее определение в Цели развития тысячелетия 7, задача 7.A, было просто долей от общего объема используемых водных ресурсов без учета EFR. [32] : 28 Это определение устанавливает несколько категорий водного стресса. Ниже 10% — низкий стресс; 10–20% — низкий или средний; 20–40% — средний или высокий; 40-80% высокий; более 80% очень высокий. [33]

Индикаторы используются для измерения степени дефицита воды. [34] Одним из способов измерения дефицита воды является расчет количества водных ресурсов, доступных на человека каждый год. Одним из примеров является «Индикатор водного стресса Фалькенмарка». Он был разработан Малин Фалькенмарк . Этот индикатор говорит, что страна или регион испытывает «водный стресс», когда годовые запасы воды падают ниже 1700 кубических метров на человека в год. [35] Уровни между 1700 и 1000 кубических метров приведут к периодической или ограниченной нехватке воды. Когда запасы воды падают ниже 1000 кубических метров на человека в год, страна сталкивается с «дефицитом воды». Однако индикатор водного стресса Фалькенмарка не помогает объяснить истинную природу дефицита воды. [3]

Также можно измерить дефицит воды, взглянув на возобновляемую пресную воду . Эксперты используют его при оценке дефицита воды. Этот показатель может описывать общие доступные водные ресурсы, которые содержит каждая страна. Этот общий доступный водный ресурс дает представление о том, склонна ли страна испытывать физический дефицит воды. [36] У этого показателя есть недостаток, поскольку он является средним. Осадки поставляют воду неравномерно по всей планете каждый год. Поэтому годовые возобновляемые водные ресурсы меняются из года в год. Этот показатель не описывает, насколько легко отдельным лицам, домохозяйствам, отраслям или правительству получить доступ к воде. Наконец, этот показатель дает описание всей страны. Поэтому он неточно отображает, испытывает ли страна дефицит воды. Например, Канада и Бразилия имеют очень высокий уровень доступного водоснабжения. Но они по-прежнему сталкиваются с различными проблемами, связанными с водой. [36] Некоторые тропические страны в Азии и Африке имеют низкий уровень ресурсов пресной воды.

Оценки дефицита воды должны включать несколько типов информации. Они включают данные о зеленой воде ( влажность почвы ), качестве воды , требованиях к экологическому стоку, глобализации и виртуальной торговле водой . [6] С начала 2000-х годов оценки дефицита воды использовали более сложные модели. Они извлекают выгоду из инструментов пространственного анализа. Зелено-голубой дефицит воды является одним из них. Оценка дефицита воды на основе следа является другим. Другим является кумулятивное отношение абстракции к спросу, которое учитывает временные изменения. Другими примерами являются индикаторы водного стресса на основе LCA и интегрированный поток воды в окружающую среду с точки зрения количества и качества. [6] С начала 2010-х годов оценки рассматривали дефицит воды как с точки зрения количества, так и с точки зрения качества. [37]

Эксперты предложили еще один индикатор. Это называется экологическим дефицитом воды . Он учитывает количество воды, качество воды и требования к экологическому стоку. [19] Результаты модельного исследования 2022 года показывают, что северный Китай пострадал от более серьезного экологического дефицита воды, чем южный Китай. Движущим фактором экологического дефицита воды в большинстве провинций было загрязнение воды, а не ее использование человеком. [19]

Успешная оценка объединит экспертов из нескольких научных дисциплин. К ним относятся гидрологические, водохозяйственные, водные экосистемные и социальные науки. [6]

По оценкам Организации Объединенных Наций , только 200 000 кубических километров из 1,4 миллиарда кубических километров воды на Земле являются пресной водой, доступной для потребления человеком. Всего 0,014% всей воды на Земле является как пресной, так и легкодоступной . [ 38] Из оставшейся воды 97% являются соленой, а чуть менее 3% труднодоступны. Пресная вода, доступная нам на планете, составляет около 1% от общего объема воды на Земле. [39] Общее количество легкодоступной пресной воды на Земле составляет 14 000 кубических километров. Это поверхностные воды, такие как реки и озера, или грунтовые воды , например, в водоносных горизонтах . Из этого общего количества человечество использует и повторно использует всего 5 000 кубических километров. Технически, в глобальном масштабе имеется достаточное количество пресной воды. Таким образом, теоретически пресной воды более чем достаточно для удовлетворения потребностей нынешнего населения мира в 8 миллиардов человек. Достаточно даже для поддержки роста населения до 9 миллиардов и более. Но неравномерное географическое распределение и неравномерное потребление воды делает ее дефицитным ресурсом в некоторых регионах и группах людей.

Реки и озера являются общими поверхностными источниками пресной воды. Но другие водные ресурсы, такие как грунтовые воды и ледники, стали более развитыми источниками пресной воды. Они стали основным источником чистой воды. Грунтовые воды — это вода, которая скапливается под поверхностью Земли. Она может обеспечить пригодное для использования количество воды через источники или скважины. Эти области грунтовых вод также известны как водоносные горизонты. Становится все труднее использовать обычные источники из-за загрязнения и изменения климата. Поэтому люди все больше и больше черпают из этих других источников. Рост населения стимулирует более широкое использование этих типов водных ресурсов. [36]

В 2019 году Всемирный экономический форум назвал дефицит воды одним из крупнейших глобальных рисков с точки зрения потенциального воздействия в течение следующего десятилетия. [40] Дефицит воды может принимать различные формы. Одна из них — неспособность удовлетворить спрос на воду, частично или полностью. Другие примеры — экономическая конкуренция за количество или качество воды, споры между пользователями, необратимое истощение грунтовых вод и негативное воздействие на окружающую среду .

Около половины населения мира в настоящее время испытывает острую нехватку воды, по крайней мере, в течение некоторого периода года. [41] Полмиллиарда человек в мире сталкиваются с острой нехваткой воды круглый год. [5] Половина крупнейших городов мира испытывают нехватку воды. [11] Почти два миллиарда человек в настоящее время не имеют доступа к чистой питьевой воде.

[42] [43] Исследование, проведенное в 2016 году, подсчитало, что число людей, страдающих от нехватки воды, увеличилось с 0,24 миллиарда или 14% мирового населения в 1900-х годах до 3,8 миллиарда (58%) в 2000-х годах. [1] В этом исследовании для анализа нехватки воды использовались две концепции. Одна из них — нехватка или последствия из-за низкой доступности на душу населения. Другая — стресс или последствия из-за высокого потребления относительно доступности.

В 20 веке потребление воды росло более чем в два раза быстрее, чем росло население. В частности, забор воды, вероятно, увеличится на 50 процентов к 2025 году в развивающихся странах и на 18 процентов в развитых странах. [44] По прогнозам , на одном континенте, например, в Африке , от 75 до 250 миллионов жителей будут лишены доступа к пресной воде. [45] К 2025 году 1,8 миллиарда человек будут жить в странах или регионах с абсолютным дефицитом воды, а две трети населения мира могут оказаться в условиях стресса. [46] К 2050 году более половины населения мира будет жить в районах с дефицитом воды, а еще миллиард может испытывать нехватку воды, обнаружили исследователи Массачусетского технологического института. [47]

С ростом глобальной температуры и ростом спроса на воду шесть из десяти человек подвергаются риску водного стресса. Высыхание водно-болотных угодий во всем мире, около 67%, стало прямой причиной большого количества людей, подверженных риску водного стресса. Поскольку глобальный спрос на воду увеличивается и температура повышается, вполне вероятно, что две трети населения будут жить в условиях водного стресса в 2025 году. [48] [39] : 191

Согласно прогнозу Организации Объединенных Наций, к 2040 году около 4,5 млрд человек могут столкнуться с водным кризисом (или нехваткой воды). Кроме того, с ростом населения возникнет спрос на продовольствие, а для того, чтобы производство продовольствия соответствовало росту населения, увеличится спрос на воду для орошения сельскохозяйственных культур. [49] Всемирный экономический форум оценивает, что к 2030 году глобальный спрос на воду превысит мировое предложение на 40%. [50] [51] Увеличение спроса на воду, а также рост населения приводит к водному кризису, когда воды недостаточно для обеспечения здоровых уровней. Кризисы обусловлены не только количеством, но и качеством.

Исследование показало, что 6-20% из примерно 39 миллионов скважин грунтовых вод подвержены высокому риску высыхания, если местные уровни грунтовых вод снизятся на несколько метров. Во многих районах и, возможно, с более чем половиной основных водоносных горизонтов [52] это применимо, если они просто продолжат снижаться. [53] [54]

Существует несколько последствий и симптомов нехватки воды. К ним относятся серьезные ограничения на использование воды. Другие — это растущий конфликт между пользователями, растущая конкуренция за воду, снижение стандартов надежности и обслуживания, неурожаи и отсутствие продовольственной безопасности. [17] : 6

Вот несколько примеров:

Контролируемые факторы, такие как управление и распределение водоснабжения, могут способствовать дефициту. В докладе Организации Объединенных Наций за 2006 год основное внимание уделяется вопросам управления как основе водного кризиса. В докладе отмечено, что: «Воды достаточно для всех». В нем также говорится: «Нехватка воды часто возникает из-за неэффективного управления, коррупции, отсутствия соответствующих учреждений, бюрократической инертности и нехватки инвестиций как в человеческий потенциал, так и в физическую инфраструктуру». [60]

Экономисты и другие утверждают, что отсутствие прав собственности , правительственные постановления и субсидии на воду привели к возникновению ситуации с водой. Эти факторы приводят к слишком низким ценам и слишком высокому потреблению, что делает необходимым приватизацию воды . [61] [62] [63]

Кризис чистой воды — это надвигающийся глобальный кризис, затрагивающий приблизительно 785 миллионов человек по всему миру. [64] 1,1 миллиарда человек не имеют доступа к воде, а 2,7 миллиарда испытывают нехватку воды по крайней мере один месяц в году. 2,4 миллиарда человек страдают от загрязненной воды и плохой санитарии. Загрязнение воды может привести к смертельным диарейным заболеваниям, таким как холера и брюшной тиф , а также другим заболеваниям, передающимся через воду . На их долю приходится 80% заболеваний во всем мире. [65]

Использование воды для бытовых, пищевых и промышленных нужд оказывает серьезное воздействие на экосистемы во многих частях мира. Это может применяться даже к регионам, которые не считаются «дефицитными». [3] Дефицит воды наносит ущерб окружающей среде многими способами. К ним относятся неблагоприятное воздействие на озера, реки, пруды, водно-болотные угодья и другие ресурсы пресной воды. Таким образом, из-за дефицита воды происходит чрезмерное ее использование. Это часто происходит в районах орошаемого земледелия. Это может нанести вред окружающей среде несколькими способами. Это включает в себя повышенную соленость , загрязнение питательными веществами и потерю пойм и водно-болотных угодий . [23] [66] Дефицит воды также затрудняет использование потока для восстановления городских ручьев. [67]

За последние сто лет более половины водно-болотных угодий Земли были уничтожены и исчезли. [9] Эти водно-болотные угодья важны как среда обитания многочисленных существ, таких как млекопитающие, птицы, рыбы, земноводные и беспозвоночные . Они также поддерживают выращивание риса и других продовольственных культур. И они обеспечивают фильтрацию воды и защиту от штормов и наводнений. Пресноводные озера, такие как Аральское море в Центральной Азии, также пострадали. Когда-то оно было четвертым по величине пресноводным озером в мире. Но за три десятилетия оно потеряло более 58 000 квадратных километров площади и значительно увеличило концентрацию соли. [9]

Проседание — еще один результат нехватки воды. Геологическая служба США оценивает, что проседание затронуло более 17 000 квадратных миль в 45 штатах США, 80 процентов из них — из-за использования грунтовых вод. [68]

Растительности и диким животным нужно достаточное количество пресной воды. Болота , топи и прибрежные зоны более явно зависят от устойчивого водоснабжения. Леса и другие горные экосистемы в равной степени подвержены риску, поскольку вода становится менее доступной. В случае водно-болотных угодий много земли было просто изъято из использования дикими животными, чтобы прокормить и обеспечить жильем растущее население. Другие районы также пострадали от постепенного снижения притока пресной воды, поскольку вода выше по течению отводится для использования человеком.

Около пятидесяти лет назад общепринятым было мнение, что вода — бесконечный ресурс. В то время на планете было меньше половины нынешнего числа людей. Люди были не так богаты, как сегодня, потребляли меньше калорий и ели меньше мяса, поэтому для производства пищи требовалось меньше воды. Им требовалась треть объема воды, который мы сейчас берем из рек. Сегодня конкуренция за водные ресурсы намного интенсивнее. Это связано с тем, что сейчас на планете живет семь миллиардов человек, и их потребление мяса, требующего много воды, растет. А промышленность , урбанизация , биотопливные культуры и продукты питания, зависящие от воды, все больше конкурируют за воду. В будущем для производства пищи потребуется еще больше воды, поскольку, по прогнозам, к 2050 году население Земли вырастет до 9 миллиардов. [69]

В 2000 году население мира составляло 6,2 миллиарда человек. По оценкам ООН, к 2050 году численность населения увеличится на 3,5 миллиарда человек, причем большая часть прироста придется на развивающиеся страны , которые уже страдают от нехватки воды. [70] Это увеличит спрос на воду, если не будет соответствующего увеличения водосбережения и переработки . [71] Основываясь на данных, представленных здесь ООН, Всемирный банк [72] продолжает объяснять, что доступ к воде для производства продовольствия станет одной из главных проблем в ближайшие десятилетия. Необходимо будет сбалансировать доступ к воде с управлением водными ресурсами устойчивым образом. В то же время необходимо будет учитывать влияние изменения климата и других экологических и социальных переменных. [73]

В 60% европейских городов с населением более 100 000 человек грунтовые воды используются быстрее, чем могут быть восполнены. [74]

Рост численности населения усиливает конкуренцию за воду. Это истощает многие из основных водоносных горизонтов мира. Это имеет две причины. Одна из них — прямое потребление человеком. Другая — сельскохозяйственное орошение. Миллионы насосов всех размеров в настоящее время извлекают грунтовые воды по всему миру. Орошение в засушливых районах, таких как северный Китай , Непал и Индия, использует грунтовые воды. И оно извлекает грунтовые воды с неустойчивой скоростью. Во многих городах произошло падение водоносных горизонтов от 10 до 50 метров. Среди них Мехико , Бангкок , Пекин , Ченнаи и Шанхай . [76]

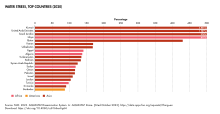

До недавнего времени грунтовые воды не были широко используемым ресурсом. В 1960-х годах развивалось все больше и больше грунтовых водоносных горизонтов. [77] Улучшенные знания, технологии и финансирование позволили больше сосредоточиться на заборе воды из грунтовых вод, а не из поверхностных. Это сделало возможной сельскохозяйственную революцию грунтовых вод. Они расширили сектор орошения, что позволило увеличить производство продовольствия и развитие в сельских районах. [78] Грунтовые воды поставляют почти половину всей питьевой воды в мире. [79] Большие объемы воды, хранящиеся под землей в большинстве водоносных горизонтов, имеют значительную буферную емкость. Это позволяет извлекать воду в периоды засухи или небольшого количества осадков. [36] Это имеет решающее значение для людей, которые живут в регионах, которые не могут зависеть от осадков или поверхностных вод в качестве своих единственных источников. Это обеспечивает надежный доступ к воде круглый год. По состоянию на 2010 год совокупный забор грунтовых вод в мире оценивается в 1000 км 3 в год. Из них 67% идет на орошение, 22% на бытовые цели и 11% на промышленные цели. [36] Десять крупнейших потребителей забираемой воды составляют 72% всего забираемого водопользования в мире. Это Индия, Китай, Соединенные Штаты Америки, Пакистан, Иран, Бангладеш, Мексика, Саудовская Аравия, Индонезия и Италия. [36]

Источники грунтовых вод довольно многочисленны. Но одной из основных проблем является скорость обновления или пополнения некоторых источников грунтовых вод. Извлечение из невозобновляемых источников грунтовых вод может истощить их, если они не контролируются и не управляются должным образом. [80] Увеличение использования грунтовых вод также может со временем снизить качество воды. Системы грунтовых вод часто демонстрируют снижение естественных оттоков, хранимых объемов и уровней воды, а также деградацию воды. [36] Истощение грунтовых вод может причинить вред многими способами. К ним относятся более дорогостоящая откачка грунтовых вод и изменения солености и других типов качества воды. Они также могут привести к проседанию земли, деградации родников и снижению базисных потоков.

Основной причиной дефицита воды в результате потребления является чрезмерное использование воды в сельском хозяйстве / животноводстве и промышленности . Люди в развитых странах обычно используют примерно в 10 раз больше воды в день, чем люди в развивающихся странах . [83] Большая часть этого — косвенное использование в водоемком сельскохозяйственном и промышленном производстве потребительских товаров . Примерами являются фрукты, масличные культуры и хлопок. Многие из этих производственных цепочек глобализированы, поэтому большое потребление воды и загрязнение в развивающихся странах происходит для производства товаров для потребления в развитых странах. [84]

Многие водоносные горизонты были перекачаны и не восполняются быстро. Это не исчерпывает весь запас пресной воды. Но это означает, что многое стало загрязненным, засоленным, непригодным или иным образом недоступным для питья, промышленности и сельского хозяйства. Чтобы избежать глобального водного кризиса, фермерам придется повысить производительность, чтобы удовлетворить растущий спрос на продовольствие. В то же время промышленность и города должны будут найти способы использовать воду более эффективно. [85]

Business activities such as tourism are continuing to expand. They create a need for increases in water supply and sanitation. This in turn can lead to more pressure on water resources and natural ecosystems. The approximate 50% growth in world energy use by 2040 will also increase the need for efficient water use.[85] It may means some water use shifts from irrigation to industry. This is because thermal power generation uses water for steam generation and cooling.[86]

Water pollution (or aquatic pollution) is the contamination of water bodies, with a negative impact on their uses.[87]: 6 It is usually a result of human activities. Water bodies include lakes, rivers, oceans, aquifers, reservoirs and groundwater. Water pollution results when contaminants mix with these water bodies. Contaminants can come from one of four main sources. These are sewage discharges, industrial activities, agricultural activities, and urban runoff including stormwater.[88] Water pollution may affect either surface water or groundwater. This form of pollution can lead to many problems. One is the degradation of aquatic ecosystems. Another is spreading water-borne diseases when people use polluted water for drinking or irrigation.[89] Water pollution also reduces the ecosystem services such as drinking water provided by the water resource.

Sources of water pollution are either point sources or non-point sources.[90] Point sources have one identifiable cause, such as a storm drain, a wastewater treatment plant or an oil spill. Non-point sources are more diffuse. An example is agricultural runoff.[91] Pollution is the result of the cumulative effect over time. Pollution may take many forms. One would is toxic substances such as oil, metals, plastics, pesticides, persistent organic pollutants, and industrial waste products. Another is stressful conditions such as changes of pH, hypoxia or anoxia, increased temperatures, excessive turbidity, or changes of salinity). The introduction of pathogenic organisms is another. Contaminants may include organic and inorganic substances. A common cause of thermal pollution is the use of water as a coolant by power plants and industrial manufacturers.Climate change could have a big impact on water resources around the world because of the close connections between the climate and hydrological cycle. Rising temperatures will increase evaporation and lead to increases in precipitation. However there will be regional variations in rainfall. Both droughts and floods may become more frequent and more severe in different regions at different times. There will be generally less snowfall and more rainfall in a warmer climate.[92] Changes in snowfall and snow melt in mountainous areas will also take place. Higher temperatures will also affect water quality in ways that scientists do not fully understand. Possible impacts include increased eutrophication. Climate change could also boost demand for irrigation systems in agriculture. There is now ample evidence that greater hydrologic variability and climate change have had a profound impact on the water sector, and will continue to do so. This will show up in the hydrologic cycle, water availability, water demand, and water allocation at the global, regional, basin, and local levels.[93]

The United Nations' FAO states that by 2025 1.9 billion people will live in countries or regions with absolute water scarcity. It says two thirds of the world's population could be under stress conditions.[94] The World Bank says that climate change could profoundly alter future patterns of water availability and use. This will make water stress and insecurity worse, at the global level and in sectors that depend on water.[95]

Scientists have found that population change is four time more important than long-term climate change in its effects on water scarcity.[48]

The continued retreat of glaciers will have a number of different quantitative effects. In areas that are heavily dependent on water runoff from glaciers that melt during the warmer summer months, a continuation of the current retreat will eventually deplete the glacial ice and substantially reduce or eliminate runoff. A reduction in runoff will affect the ability to irrigate crops and will reduce summer stream flows necessary to keep dams and reservoirs replenished. This situation is particularly acute for irrigation in South America, where numerous artificial lakes are filled almost exclusively by glacial melt.[96] Central Asian countries have also been historically dependent on the seasonal glacier melt water for irrigation and drinking supplies. In Norway, the Alps, and the Pacific Northwest of North America, glacier runoff is important for hydropower.

In the Himalayas, retreating glaciers could reduce summer water flows by up to two thirds. In the Ganges area, this would cause a water shortage for 500 million people.[97] In the Hindu Kush Himalaya area, around 1.4 billion people are dependent on the five main rivers of the Himalaya mountains.[98] Although the impact will vary from place to place, the amount of meltwater is likely to increase at first as glaciers retreat. Then it will gradually decrease because of the fall in glacier mass.[99][100]A review in 2006 stated that "It is surprisingly difficult to determine whether water is truly scarce in the physical sense at a global scale (a supply problem) or whether it is available but should be used better (a demand problem)".[101]

The International Resource Panel of the UN states that governments have invested heavily in inefficient solutions. These are mega-projects like dams, canals, aqueducts, pipelines and water reservoirs. They are generally neither environmentally sustainable nor economically viable.[102] According to the panel, the most cost-effective way of decoupling water use from economic growth is for governments to create holistic water management plans. These would take into account the entire water cycle: from source to distribution, economic use, treatment, recycling, reuse and return to the environment.

In general, there is enough water on an annual and global scale. The issue is more of variation of supply by time and by region. Reservoirs and pipelines would deal with this variable water supply. Well-planned infrastructure with demand side management is necessary. Both supply-side and demand-side management have advantages and disadvantages.[citation needed]

Lack of cooperation may give rise to regional water conflicts. This is especially the case in developing countries. The main reason is disputes regarding the availability, use and management of water.[59] One example is the dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam which escalated in 2020.[103][104] Egypt sees the dam as an existential threat, fearing that the dam will reduce the amount of water it receives from the Nile.[105]

Water conservation aims to sustainably manage the natural resource of fresh water, protect the hydrosphere, and meet current and future human demand. Water conservation makes it possible to avoid water scarcity. It covers all the policies, strategies and activities to reach these aims. Population, household size and growth and affluence all affect how much water is used.

Climate change and other factors have increased pressure on natural water resources. This is especially the case in manufacturing and agricultural irrigation.[106] Many countries have successfully implemented policies to conserve water conservation.[107] There are several key activities to conserve water. One is beneficial reduction in water loss, use and waste of resources.[108] Another is avoiding any damage to water quality. A third is improving water management practices that reduce the use or enhance the beneficial use of water.[109][110]Wastewater treatment is a process which removes and eliminates contaminants from wastewater. It thus converts it into an effluent that can be returned to the water cycle. Once back in the water cycle, the effluent creates an acceptable impact on the environment. It is also possible to reuse it. This process is called water reclamation.[117] The treatment process takes place in a wastewater treatment plant. There are several kinds of wastewater which are treated at the appropriate type of wastewater treatment plant. For domestic wastewater the treatment plant is called a Sewage Treatment. Municipal wastewater or sewage are other names for domestic wastewater. For industrial wastewater, treatment takes place in a separate Industrial wastewater treatment, or in a sewage treatment plant. In the latter case it usually follows pre-treatment. Further types of wastewater treatment plants include Agricultural wastewater treatment and leachate treatment plants.

One common process in wastewater treatment is phase separation, such as sedimentation. Biological and chemical processes such as oxidation are another example. Polishing is also an example. The main by-product from wastewater treatment plants is a type of sludge that is usually treated in the same or another wastewater treatment plant.[118]: Ch.14 Biogas can be another by-product if the process uses anaerobic treatment. Treated wastewater can be reused as reclaimed water.[119] The main purpose of wastewater treatment is for the treated wastewater to be able to be disposed or reused safely. However, before it is treated, the options for disposal or reuse must be considered so the correct treatment process is used on the wastewater.The virtual water trade is the hidden flow of water in food or other commodities that are traded from one place to another.[123] Other terms for it are embedded or embodied water. The virtual water trade is the idea that virtual water is exchanged along with goods and services. This idea provides a new, amplified perspective on water problems. It balances different perspectives, basic conditions, and interests. This concept makes it possible to distinguish between global, regional, and local levels and their linkages. However, the use of virtual water estimates may offer no guidance for policymakers seeking to ensure they are meeting environmental objectives.

For example, cereal grains have been major carriers of virtual water in countries where water resources are scarce. So cereal imports can compensate for local water deficits.[124] However, low-income countries may not be able to afford such imports in the future. This could lead to food insecurity and starvation.

The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) published a map showing the countries and regions suffering most water stress.[126] They are North Africa, the Middle East,[127] India, Central Asia, China, Chile, Colombia, South Africa, Canada and Australia. Water scarcity is also increasing in South Asia.[128] As of 2016, about four billion people, or two thirds of the world's population, were facing severe water scarcity.[129]

The more developed countries of North America, Europe and Russia will not see a serious threat to water supply by 2025 in general. This is not only because of their relative wealth. Their populations will also be more in line with available water resources.[citation needed] North Africa, the Middle East, South Africa and northern China will face very severe water shortages. This is due to physical scarcity and too many people for the water that is available.[citation needed] Most of South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, southern China and India will face water supply shortages by 2025. For these regions, scarcity will be due to economic constraints on developing safe drinking water, and excessive population growth.[citation needed]

The main causes of water scarcity in Africa are physical and economic water scarcity, rapid population growth, and the effects of climate change on the water cycle. Water scarcity is the lack of fresh water resources to meet the standard water demand.[131] The rainfall in sub-Saharan Africa is highly seasonal and unevenly distributed, leading to frequent floods and droughts.[132]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reported in 2012 that growing water scarcity is now one of the leading challenges for sustainable development.[133] This is because an increasing number of river basins have reached conditions of water scarcity. The reasons for this are the combined demands of agriculture and other sectors. Water scarcity in Africa has several impacts. They range from health, particularly affecting women and children, to education, agricultural productivity and sustainable development. It can also lead to more water conflicts.Water scarcity in Yemen (see: Water supply and sanitation in Yemen) is a growing problem. Population growth and climate change are among the causes. Others are poor water management, shifts in rainfall, water infrastructure deterioration, poor governance, and other anthropogenic effects. As of 2011, water scarcity is having political, economic and social impacts in Yemen. As of 2015,[134] Yemen is one of the countries suffering most from water scarcity. Most people in Yemen experience water scarcity for at least one month a year.

In Nigeria, some reports have suggested that increase in extreme heat, drought and the shrinking of Lake Chad is causing water shortage and environmental migration. This is forcing thousands to migrate to neighboring Chad and towns.[135]

A major report in 2019 by more than 200 researchers, found that the Himalayan glaciers could lose 66 percent of their ice by 2100.[136] These glaciers are the sources of Asia's biggest rivers – Ganges, Indus, Brahmaputra, Yangtze, Mekong, Salween and Yellow. Approximately 2.4 billion people live in the drainage basin of the Himalayan rivers.[137] India, China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Myanmar could experience floods followed by droughts in coming decades. In India alone, the Ganges provides water for drinking and farming for more than 500 million people.[138][139][140]

Even with the overpumping of its aquifers, China is developing a grain deficit. When this happens, it will almost certainly drive grain prices upward. Most of the 3 billion people projected to be added worldwide by mid-century will be born in countries already experiencing water shortages. Unless population growth can be slowed quickly, it is feared that there may not be a practical non-violent or humane solution to the emerging world water shortage.[141][142]

It is highly likely that climate change in Turkey will cause its southern river basins to be water scarce before 2070, and increasing drought in Turkey.[143]

In the Rio Grande Valley, intensive agribusiness has made water scarcity worse. It has sparked jurisdictional disputes regarding water rights on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. Scholars such as Mexico's Armand Peschard-Sverdrup have argued that this tension has created the need for new strategic transnational water management.[145] Some have likened the disputes to a war over diminishing natural resources.[146][147]

The west coast of North America, which gets much of its water from glaciers in mountain ranges such as the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada, is also vulnerable.[148][149]

By far the largest part of Australia is desert or semi-arid lands commonly known as the outback.[150] Water restrictions are in place in many regions and cities of Australia in response to chronic shortages resulting from drought. Environmentalist Tim Flannery predicted that Perth in Western Australia could become the world's first ghost metropolis. This would mean it was an abandoned city with no more water to sustain its population, said Flannery, who was Australian of the year 2007.[151] In 2010, Perth suffered its second-driest winter on record[152] and the water corporation tightened water restrictions for spring.[153]

Some countries have already proven that decoupling water use from economic growth is possible. For example, in Australia, water consumption declined by 40% between 2001 and 2009 while the economy grew by more than 30%.[102]

Water scarcity or water crisis in particular countries:

Sustainable Development Goal 6 aims for clean water and sanitation for all.[154] It is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015. The fourth target of SDG 6 refers to water scarcity. It states: "By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity".[10] It has two indicators. The second one is: "Level of water stress: freshwater withdrawal as a proportion of available freshwater resources". The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has been monitoring these parameters through its global water information system, AQUASTAT[1] since 1994.[32]: xii

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)![]() Environment portal

Environment portal![]() Water portal

Water portal![]() World portal

World portal