Палатины ( нем. Palatine : Pälzer ) были гражданами и князьями Пфальца , Священной Римской империи , которая служила столицей императора Священной Римской империи . [1] [2] [3] После падения Священной Римской империи в 1806 году национальность стала относиться более конкретно к жителям Рейнского Пфальца , известного просто как «Пфальц». [4]

Американские пфальцграфы , включая пенсильванских голландцев , сохраняли свое присутствие в Соединенных Штатах с 1632 года и известны под общим названием «пфальцские голландцы» ( Palantine German : Pälzisch Deitsche ). [5] [6] [7]

Термин palatine или palatinus впервые был использован в Римской империи для обозначения камергеров императора (например, камергер Святой Римской церкви ) из-за их связи с Палатинским холмом , домом, где жили римские императоры со времен Августа Цезаря (и откуда « дворец »). [8]

После падения Древнего Рима в обиход вошёл новый феодальный тип титула, известный просто как palatinus . Comes palatinus ( палатинский граф ) помогал императору Священной Римской империи в его судебных обязанностях и позднее сам управлял многими из них. Другие палатинские графы были заняты на военной и административной работе. [9]

Император Священной Римской империи посылал пфальцграфов в различные части своей империи, чтобы они действовали в качестве судей и губернаторов; государства, которыми они управляли, назывались палатинатами . [10] Будучи в особом смысле представителями императора Священной Римской империи, они были наделены более обширной властью, чем обычные графы. Таким образом, произошло позднее и более общее использование слова «палатин», его применение в качестве прилагательного к лицам, наделенным королевскими полномочиями и привилегиями Священной Римской империи, а также к государствам и людям, которыми они управляли. [9]

Пфальцграфы были постоянными представителями императора Священной Римской империи в дворцовом домене (Пфальце) короны. В ранней империи существовало несколько десятков таких королевских пфальцграфств ( Пфальцев ), и император путешествовал между ними, поскольку не было имперской столицы.

В империи термин «граф пфальцграф» также использовался для обозначения должностных лиц, которые помогали императору в осуществлении прав, которые были зарезервированы для его личного рассмотрения, [9] например, дарование оружия . Их называли императорскими пфальцграфами (на латыни comites palatini caesarii или comites sacri palatii ; на немецком языке Hofpfalzgrafen ). Как латинская форма (Comes) palatinus , так и французская (comte) palatin использовались как часть полного титула герцогов Бургундии (ветвь французской королевской династии) для передачи их редкого немецкого титула Freigraf , который был стилем (позже утраченного) пограничного княжества, аллодиального графства Бургундия ( Freigrafschaft Burgund на немецком языке), которое стало известно как Франш-Конте .

В XI веке некоторые имперские пфальцграфы стали ценным политическим противовесом могущественным герцогствам. Сохранившиеся старые пфальцграфства были превращены в новые институциональные столпы, через которые могла осуществляться имперская власть. Во времена правления Генриха Птицелова и особенно Оттона Великого comites palatini были отправлены во все части страны, чтобы поддержать королевскую власть , контролируя независимые тенденции великих племенных герцогов. После этого стало очевидным существование пфальцграфа в Саксонии и других в Лотарингии, Баварии и Швабии, их обязанностями было управление королевскими поместьями в этих герцогствах. [9]

Наряду с герцогами Лотарингии , Баварии , Швабии и Саксонии , которые стали опасно могущественными феодальными князьями, верные сторонники императора Священной Римской империи были назначены пфальцграфами.

Палатины Лотарингии из династии Эццонидов были важными командирами императорской армии и часто использовались во время внутренних и внешних конфликтов (например, для подавления мятежей графов или герцогов, для урегулирования пограничных споров с Венгерским и Французским королевствами и для руководства имперскими походами).

Хотя пфальц мог десятилетиями быть укоренён в одной династии, должность пфальцграфов стала наследственной только в XII веке. В XI веке пфальцграфы всё ещё считались бенефициями , ненаследственными феодами. Пфальцграф Баварии, должность, занимаемая семьей Виттельсбахов, стал герцогом этой земли, а низший графский титул затем был объединён с высшим герцогским. [9] Пфальцграф Лотарингии изменил своё имя на пфальцграфа Рейнского в 1085 году, оставаясь единственным независимым до 1777 года. После того как должность стала наследственной, пфальцграфы просуществовали до распада Священной Римской империи в 1806 году. [9] Пфальц Саксонии объединился с курфюршеством Саксонии. Пфальц Рейнский стал курфюршеством, и оба стали императорскими викариями .

Король Франции Лотарь (954–986) в 976 году даровал Одо I , графу Блуа , одному из своих самых верных сторонников в борьбе с Робертианцами и графами Вермандуа , титул пфальцграфа. Позже этот титул перешел по наследству его наследникам, а когда они вымерли, — графам Шампани .

Первоначально пфальцграфы владели пфальцграфством вокруг Регенсбурга и подчинялись герцогам Баварии , а не королю. Должность давала ее владельцу ведущее положение в правовой системе герцогства.

С 985 года Эззониды носили титул:

Пфальцграфство Лотарингия было отстранено императором. Аделаида Веймар-Орламюндская, вдова Германа II, снова вышла замуж за Генриха фон Лааха . Около 1087 года он был назначен на недавно созданную должность пфальцграфа Рейнского .

В 1085 году, после смерти Германа II, пфальцграфство Лотарингия утратило свое военное значение в Лотарингии. Территориальная власть пфальцграфа была сведена к его территориям вдоль Рейна. Соответственно, после 1085 года он именуется пфальцграфом Рейна .

Золотая булла 1356 года сделала пфальцграфа Рейнского курфюрстом . Поэтому он был известен как курфюрст Пфальц .

В X веке император Оттон I создал пфальцграфство Саксонское в районе Заале-Унструт в южной Саксонии. Первоначально эта честь принадлежала графу Гессенгау , затем с начала XI века графам Гозек , позднее графам Зоммершенбург, а еще позже ландграфам Тюрингии :

После смерти Генриха Распе пфальцграфство Саксонское и ландграфство Тюрингия были переданы династии Веттинов на основании обещания, данного императором Фридрихом II:

Король Германии Рудольф I передал пфальцграфство Саксонию династии Вельфов :

Писцы Священной Римской империи часто использовали термин Швабия как синоним Аламаннии в период с X по XII века. [11]

После 1146 года титул перешел к пфальцграфам Тюбингенским .

В 1169 году император Фридрих I создал Вольное графство Бургундия (не путать с его западным соседом, герцогством Бургундия ). Графы Бургундии имели титул Вольных графов ( ‹См. Tfd› на немецком: Freigraf ), но иногда их называли графами пфальцграфами.

_issued_by_W._Duke,_Sons_&_Co._MET_DPB873799.jpg/440px-Pope_Leo_XIII,_Roman_States,_from_the_Rulers,_Flags,_and_Coats_of_Arms_series_(N126-1)_issued_by_W._Duke,_Sons_&_Co._MET_DPB873799.jpg)

Папский граф-палатин ( Comes palatinus lateranus , правильно Comes sacri Lateranensis palatii «Граф Священного Латеранского дворца» [12] ) начал присваиваться папой в XVI веке. Этот титул был просто почетным и к XVIII веку стал присваиваться так широко, что почти не имел последствий.

Орден Золотой шпоры начал ассоциироваться с наследуемым дворянским титулом в форме графского пфальцграфства в эпоху Возрождения ; император Фридрих III в 1469 году пожаловал Бальдо Бартолини, профессору гражданского права в Университете Перуджи , титул графа пфальцграфа, что в свою очередь дало ему право присваивать университетские степени . [13]

Папа Лев X назначил всех секретарей папской курии Comites aulae Lateranensis («Графы Латеранского двора») в 1514 году и даровал им права, аналогичные правам императорского пфальцграфа . [ требуется ссылка ] В некоторых случаях титул присваивался особо уполномоченными папскими легатами . Если императорский пфальцграф обладал как императорским, так и папским назначением, он носил титул «Comes palatine imperiali Papali et auctoritate» (пфальцграф по императорской и папской власти).

Орден Золотой шпоры, связанный с титулом пфальцграфа, широко раздавался после разграбления Рима в 1527 году Карлом V, императором Священной Римской империи ; текст сохранившихся дипломов предоставлял получателям наследственное дворянство.

Среди получателей был Тициан (1533), который написал конный портрет Карла. [14] Сразу после смерти императора в 1558 году его повторное открытие в папских руках приписывается папе Пию IV в 1559 году. [15] Бенедикт XIV ( In Supremo Militantis Ecclesiæ , 1746) даровал рыцарям Гроба Господня право использовать титул графа Священного Латеранского дворца. [ необходима цитата ]

К середине XVIII века орден Золотой шпоры раздавался настолько без разбора, что Казанова заметил: «Орден, который они называют Золотой шпорой, был настолько унижен, что люди сильно раздражали меня, когда спрашивали о подробностях моего креста»; [16]

Орден был предоставлен «тем, кто находится в папском правительстве, художникам и другим, кого папа сочтет достойными награды. Он также дается иностранцам, не требуя никаких других условий, кроме исповедания католической религии» [17] .

В рамках Имперской реформы в 1500 году было создано шесть имперских округов ; еще четыре были созданы в 1512 году. Это были региональные группировки большинства (хотя и не всех) различных государств империи для целей обороны, имперского налогообложения, надзора за чеканкой монет, функций по поддержанию мира и общественной безопасности. Каждый округ имел свой собственный парламент, известный как Kreistag («Кружковой сейм»), и одного или нескольких директоров, которые координировали дела округа. Не все имперские территории были включены в имперские округа, даже после 1512 года; Земли Богемской короны были исключены, как и Швейцария , имперские феоды в северной Италии, земли Имперских рыцарей и некоторые другие небольшие территории, такие как Лордство Йевер .

Территории Пфальца на левом берегу Рейна были аннексированы революционной Францией в 1795 году, в основном став частью департамента Мон-Тоннер . Пфальцский курфюрст Максимилиан Жозеф принял потерю этих территорий после Парижского договора . [18] Те, что справа, были взяты пфальцским курфюрстом Бадена после того, как наполеоновская Франция распустила Священную Римскую империю 26 декабря 1805 года с Пресбургским миром в результате французской победы в битве трех императоров (2 декабря); оставшиеся территории Виттельсбахов были объединены Максимилианом Жозефом в Королевство Бавария . [19]

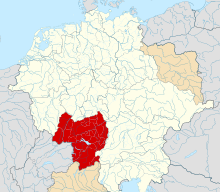

После распада Священной Римской империи в 1806 году пфальцская национальность стала более конкретно относиться к народу Рейнского Пфальца ( ‹См. Tfd› на немецком языке : Rhoipfalz ) на протяжении всего 19 века. Союз Рейнского Пфальца с Баварией был окончательно расторгнут после реорганизации немецких государств во время оккупации Германии союзниками после Второй мировой войны . Сегодня Пфальц занимает примерно самую южную четверть немецкой федеральной земли Рейнланд -Пфальц ( Рейнланд-Пфальц ).

.jpg/440px-Foot_soldiers_in_a_battle,_a_burning_village_beyond_(by_Sebastian_Vrancx).jpg)

Во второй половине XVII века Пфальц еще не полностью оправился от разрушений Тридцатилетней войны (1618–1648), в которой большая часть региона потеряла более двух третей своего населения. Первые миграции пфальцских жителей начались во время Пфальцской кампании , которая сопровождалась тяжелыми боями в Пфальце, крахом экономики государства и массовой резней населения региона, включая женщин, детей и некомбатантов. [20]

Еще в 1632 году католические палатины нашли свой путь в Мэрилендский палатинат , основанный семьей Калверт (лорды Балтимора) как убежище для католических беженцев. Самая большая концентрация палатинов обосновалась в Западном Мэриленде. [21] [22] [23]

На протяжении Девятилетней войны (1688–1697) и войны за испанское наследство (1701–1714) повторяющиеся вторжения французской армии опустошали территорию современной Юго-Западной Германии. Во время Девятилетней войны французы использовали политику выжженной земли в Пфальце.

Разграбления французской армии и разрушение многочисленных городов (особенно в Пфальце) создали экономические трудности для жителей региона, усугубленные чередой суровых зим и плохих урожаев, которые вызвали голод в Германии и большей части северо-западной Европы. Конкретным фоном миграции из Пфальца, как зафиксировано в петициях эмигрантов об отъезде, зарегистрированных в юго-западных княжествах, было обнищание и отсутствие экономических перспектив. [24]

Эмигранты прибыли в основном из регионов, включающих в себя современный Рейнланд-Пфальц , Гессен и северные районы Баден-Вюртемберга вдоль нижнего Неккара . В течение так называемого периода Kleinstaaterei («малого государства»), когда произошла эта эмиграция, регион Среднего Рейна представлял собой лоскутное одеяло из светских и церковных княжеств, герцогств и графств. Не более половины так называемых Палатинов произошли из одноименного курфюршества Пфальц , а остальные происходили из соседних имперских государств Пфальц-Цвайбрюккен и Нассау-Саарбрюккен , маркграфства Баден , гессенских ландграфств Гессен-Дармштадт , Гессен-Гомбург , Гессен-Кассель , архиепископств Трир и Майнц , а также различных мелких графств Нассау , Сайн , Зольмс , Вид и Изенбург . [25]

Массовую эмиграцию в 1709 году в основном бедных людей в Англию спровоцировало обещание Короны бесплатной земли в Британской Америке. В 1711 году парламент обнаружил, что несколько «агентов», работающих от имени провинции Каролина , обещали крестьянам вокруг Франкфурта и к югу от него бесплатный проход на плантации. Воодушевленные успехом нескольких десятков семей годом ранее, тысячи немецких семей направились вниз по Рейну в Англию и Новый Свет. [26]

Первые лодки, заполненные беженцами, начали прибывать в Лондон в начале мая 1709 года. Первые 900 человек, прибывших в Англию, были обеспечены жильем, едой и припасами несколькими богатыми англичанами. [27] Иммигрантов называли «бедными палатинами»: «бедными» в связи с их жалким и нищим положением по прибытии в Англию, и «палатинами», поскольку многие из них были выходцами из земель, контролируемых курфюрстом Пфальцским .

Большинство из них приехали из регионов вокруг Рейнского Пфальца и, вопреки воле своих правителей, они бежали тысячами на маленьких лодках и кораблях вниз по реке Рейн в голландский город Роттердам , откуда большинство отправилось в Лондон. В течение лета корабли выгрузили тысячи беженцев, и почти сразу же их количество превзошло первоначальные попытки обеспечить их. К лету большинство бедных пфальцграфов были размещены в армейских палатках на полях Блэкхита и Камбервелла . Комитет, призванный координировать их поселение и расселение, искал идеи для их трудоустройства. Это оказалось трудным, поскольку бедные пфальцграфы отличались от предыдущих групп мигрантов — квалифицированных, среднего класса, религиозных изгнанников, таких как гугеноты или голландцы в 16 веке, — а скорее были неквалифицированными сельскими рабочими, не достаточно образованными и не достаточно здоровыми для большинства видов работы.

Во время правления королевы Анны (1702–1714) политическая поляризация усилилась. Иммиграция и убежище долгое время были предметом дебатов, от кофеен до парламента, и Бедные Палатины неизбежно оказались под политическим перекрестным огнем. [28]

Для вигов , контролировавших парламент, эти иммигранты предоставили возможность увеличить рабочую силу Британии. Всего за два месяца до немецкого притока парламент принял Закон о натурализации иностранных протестантов 1708 года , согласно которому иностранные протестанты могли заплатить небольшую плату за натурализацию. Обоснованием было убеждение, что рост населения создает больше богатства, и что процветание Британии может возрасти с размещением определенных иностранцев. Британия уже извлекла выгоду из французских беженцев-гугенотов, а также голландских (или «фламандских») изгнанников, которые помогли революционизировать английскую текстильную промышленность. [29] Аналогичным образом, пытаясь увеличить симпатию и поддержку этих беженцев, многие трактаты и памфлеты вигов описывали Палатин как «беженцев совести» и жертв католического гнета и нетерпимости. Людовик XIV Французский стал печально известен преследованием протестантов в своем королевстве. Вторжение и разрушение Рейнской области его войсками многими в Британии рассматривалось как знак того, что Палатины также были объектами его религиозной тирании. При королевской поддержке виги сформулировали благотворительную инициативу по сбору средств для «бедных бедствующих Палатинов», которые стали слишком многочисленными, чтобы их могла содержать только корона. [30]

Тори и члены Высокой церковной партии (те, кто стремился к большему религиозному единообразию) были встревожены количеством бедных пфальцграфов, скапливающихся на полях юго-восточного Лондона. Давние противники натурализации, тори осудили утверждения вигов о том, что иммигранты будут полезны для экономики, поскольку они уже были тяжелым финансовым бременем. Аналогичным образом, многие, кто беспокоился о безопасности Церкви Англии, были обеспокоены религиозной принадлежностью этих немецких семей, особенно после того, как выяснилось, что многие из них (возможно, более 2000) были католиками. [31] Хотя большинство католических пфальцграфов были немедленно отправлены обратно через Ла-Манш, многие англичане считали, что их присутствие опровергает заявленный религиозный статус беженцев бедных пфальцграфов.

Автор Даниэль Дефо был главным оратором, который нападал на критиков политики правительства. Defoe's Review , трехнедельный журнал, посвященный, как правило, экономическим вопросам, в течение двух месяцев был посвящен осуждению заявлений оппонентов о том, что пфальцграфы были зараженными болезнями, католическими бандитами, которые прибыли в Англию, «чтобы есть хлеб из уст нашего народа». [32] Помимо развеивания слухов и пропаганды преимуществ увеличения населения, Дефо выдвигал собственные идеи о том, как следует «распорядиться» бедными пфальцграфами.

Вскоре после прибытия Палатинов Торговому совету было поручено найти способ их расселения. Вопреки желаниям иммигрантов, которые хотели переселиться в Британскую Америку, большинство планов предполагало их расселение на Британских островах, либо на необитаемых землях в Англии, либо в Ирландии (где они могли бы пополнить численность протестантского меньшинства). Большинство должностных лиц, причастных к этому, не хотели отправлять Палатинов в Америку из-за стоимости и убеждения, что они будут более полезны, если останутся в Британии. Поскольку большинство Бедных Палатинов были земледельцами, виноградарями и рабочими, англичане посчитали, что им лучше подойдет сельскохозяйственная сфера. Были предприняты некоторые попытки расселить их по соседним городам и поселкам. [33] В конечном итоге, крупномасштабные планы поселения ни к чему не привели, и правительство отправляло Палатинов по частям в различные регионы Англии и Ирландии. Эти попытки в основном провалились, и многие из Палатинов вернулись из Ирландии в Лондон в течение нескольких месяцев, в гораздо худшем состоянии, чем когда они уехали. [34]

Комиссары в конце концов согласились и отправили многочисленные семьи в Нью-Йорк для производства военно-морских припасов в лагерях вдоль реки Гудзон. Палатины, перевезенные в Нью-Йорк летом 1710 года, насчитывали около 2800 человек на десяти кораблях, самая большая группа иммигрантов, прибывших в Британскую Америку до Американской революции . Из-за их статуса беженцев и ослабленного состояния, а также болезней на борту, у них был высокий уровень смертности. Их держали в карантине на острове в гавани Нью-Йорка, пока болезни на борту не прошли. Еще около 300 Палатинов достигли Каролины. Несмотря на окончательный провал усилий по созданию военно-морских припасов и задержки с предоставлением им земли в заселенных районах (им были предоставлены гранты на границах), они достигли Нового Света и были полны решимости остаться. Их потомки разбросаны по Соединенным Штатам и Канаде.

Опыт с бедными Палатинами дискредитировал философию натурализации вигов и фигурировал в политических дебатах как пример пагубных последствий предоставления убежища беженцам. Как только тори вернулись к власти, они отменили Акт о натурализации, который, как они утверждали, заманил Палатинов в Англию (хотя на самом деле натурализовались лишь немногие). [35] Более поздние попытки восстановить Акт о натурализации страдали от запятнанного наследия первой попытки Великобритании поддержать массовую иммиграцию иностранного происхождения.

В 1709 году около 3073 палатинов были перевезены в Ирландию. [36] Около 538 семей были поселены в качестве сельскохозяйственных арендаторов в поместьях англо-ирландских землевладельцев. Однако многим из поселенцев не удалось обосноваться на постоянной основе, и 352 семьи, как сообщается, покинули свои владения, многие вернулись в Англию. [37] К концу 1711 года в Ирландии осталось только около 1200 палатинов. [36]

Некоторые современные мнения обвиняли Палатинов в провале урегулирования. Уильям Кинг , архиепископ Дублинской церкви Ирландии , сказал: «Я понимаю, что их замысел заключается в том, чтобы есть и пить за счет Ее Величества, жить праздно и жаловаться на тех, кто их содержит». Но настоящей причиной неудачи, по-видимому, было отсутствие политической поддержки урегулирования со стороны тори Высокой церкви, которые в целом выступали против иностранного вмешательства и видели в поселенцах потенциальных диссентеров , а не опору своей собственной устоявшейся церкви . [36]

The Palatine settlement was successful in two areas: Counties Limerick and Wexford. In Limerick, 150 families were settled in 1712 on the lands of the Southwell family near Rathkeale. Within a short time, they had made a success of farming hemp, flax, and cattle. In Wexford about the same time, a large Palatine population was settled on the lands of Abel Ram, near Gorey. The distinctive Palatine way of life survived in these areas until well into the nineteenth century. Today, names of Palatine origin, such as Switzer, Hick, Ruttle, Sparling, Tesky, Fitzell, and Gleasure are dispersed throughout Ireland.[37][dead link]

Palatines had trickled into British America since their earliest days. The first mass migration, however, began in 1708. Queen Anne's government had sympathy for the Palatines and had invited them to go to America and work in trade for passage. Official correspondence in British records shows a combined total of 13,146 refugees traveled down the Rhine and or from Amsterdam to England in the summer of 1709.[38] More than 3,500 of these were returned from England either because they were Roman Catholic or at their own request.[39] Henry Z Jones, Jr. quotes an entry in a churchbook by the Pastor of Dreieichenhain that states a total of 15,313 Palatines left their villages in 1709 "for the so-called New America and, of course, Carolina".[40]

The flood of immigration overwhelmed English resources. It resulted in major disruptions, overcrowding, famine, disease and the death of a thousand or more Palatines. It appeared the entire Palatinate would be emptied before a halt could be called to emigration.[41] Many reasons have been given to explain why so many families left their homes for an unknown land. Knittle summarizes them: "(1) war devastation, (2) heavy taxation, (3) an extraordinarily severe winter, (4) religious quarrels, but not persecutions, (5) land hunger on the part of the elderly and desire for adventure on the part of the young, (6) liberal advertising by colonial proprietors, and finally (7) the benevolent and active cooperation of the British government."[42]

No doubt the biggest impetus was the harsh, cold winter that preceded their departure. Birds froze in mid-air, casks of wine, livestock, and whole vineyards were destroyed by the unremitting cold.[43] With what little was left of their possessions, the refugees made their way on boats down the Rhine to Amsterdam, where they remained until the British government decided what to do about them. Ships were finally dispatched for them across the English Channel, and the Palatines arrived in London, where they waited longer while the British government considered its options. So many arrived that the government created a winter camp for them outside the city walls. A few were settled in England, a few more may have been sent to Jamaica and Nassau, but the greatest numbers were sent to Ireland, Carolina and especially, New York in the summer of 1710. They were obligated to work off their passage.

The Reverend Joshua Kocherthal paved the way in 1709, with a small group of fifty who settled in Newburgh, New York, on the banks of the Hudson River. "In the summer of 1710, a colony numbering 2,227 arrived in New York and were [later] located in five villages on either side of the Hudson, those upon the east side being designated as East Camp, and those upon the west, as West Camp."[44] A census of these villages on 1 May 1711 showed 1194 on the east side and 583 on the west side. The total number of families was 342 and 185, respectively.[45] About 350 Palatines had remained in New York City, and some settled in New Jersey. Others travelled down the Susquehanna River, settling in Berks County, Pennsylvania. The locations of the New Jersey communities correlate with the foundation of the oldest Lutheran churches in that state, i.e., the first called Zion at New Germantown (now Oldwick), Hunterdon County; the 'Straw Church' now called St. James at Greenwich Township, Sussex (now Pohatong Township, Warren County); and St. Paul's at Pluckemin, Bedminster Township, Somerset County.

.jpg/440px-Robert_Livingston_(1654-1728).jpg)

Settlement by Palatines on the east side (East Camp) of the Hudson River was accomplished as a result of Governor Hunter's negotiations with Robert Livingston, who owned Livingston Manor in what is now Columbia County, New York (unrelated to Livingston Manor on the west side of the Hudson River). Livingston was anxious to have his lands developed. The Livingstons benefited for many years from the revenues they received as a result of this business venture. West Camp, on the other hand, was located on land the Crown had recently "repossessed" as an "extravagant grant". Pastors from both Lutheran and Reformed churches quickly began to serve the camps and created extensive records of these early settlers and their life passages long before the state of New York was established or kept records.

The British Crown believed that the Palatines could work and be "useful to this kingdom, particularly in the production of naval stores, and as a frontier against the French and their Indians".[46] Naval stores which the British needed were hemp, tar and pitch, poor choices given the climate and the variety of pine trees in New York State. On 6 September 1712, work was halted. "The last day of the government subsistence for most of the Palatines was September 12th."[47] "Within the next five years, many Palatines moved elsewhere. Several went to Pennsylvania, others to New Jersey, settling at Oldwick or Hackensack, still others pushed a few miles south to Rhinebeck, New York, and some returned to New York City, while quite a few established themselves on Livingston Manor [where they had originally been settled]. Some forty or fifty families went to Schoharie between September 12th and October 31, 1712."[48]

In the winter of 1712–13, six Palatines approached the Mohawk clan mothers to ask for permission to settle in the Schoharie River valley, a tributary of the Mohawk River.[49] The clan mothers, moved by the story of their misery and suffering, granted the Palatines permission to settle; in the spring of 1713 about 150 Palatine families moved into the Schoharie valley.[50] The Palatines had not understood that the Haudenosaunee were a matrilineal kinship society, and that the clan mothers had considerable power. They headed the nine clans that made up the Five Nations. The Palatines had expected to meet male sachems rather than these women, but property and descent were passed through the maternal lines.

A report in 1718 placed 224 families of 1,021 persons along the Hudson River while 170 families of 580 persons were in the Schoharie valley.[51] In 1723, under Governor Burnet, 100 heads of families from the work camps were settled on 100 acres (0.40 km2) each in the Burnetsfield Patent midway in the Mohawk River Valley, just west of Little Falls. They were the first Europeans to be allowed to buy land that far west in the valley.

After hearing Palatine accounts of poverty and suffering, the clan mothers granted permission for them to settle in the Schoharie Valley.[49] The women elders had their own motives. During the 17th century, the Haudenosaunee had suffered high mortality from new European infectious diseases, to which they had no immunity. They also had been engaged in warfare against the French and against other indigenous tribes. Finally, in the 1670s–80s French Jesuit missionaries had converted thousands of Iroquois (mostly Mohawk) to Catholicism and persuaded the converts to settle near Montreal.[52]

Historians referred to the Haudenosaunee who moved to New France as the Canadian Iroquois, while those who remained behind are described as the League Iroquois. At the beginning of the 17th century, about 2,000 Mohawk lived in the Mohawk River Valley, but by the beginning of the 18th century, the population had dropped to about 600 people. They were in a weakened position for resisting encroachment by English settlers.[52] The governors of New York had showed a tendency to grant Haudenosaunee land to British settlers without permission. The clan mothers believed that leasing land to the poor Palatines was a preemptive way to block the governors from granting their land to land-hungry immigrants from the British isles.[52] In their turn, the British authorities believed that the Palatines would serve as a protective barrier, providing a reliable militia who would stop French and Indigenous raiders coming down from New France (modern Canada).[53] The Palatine communities gradually extended along both sides of the Mohawk River to Canajoharie. Their legacy was reflected in place names, such as German Flatts and Palatine Bridge, and the few colonial-era churches and other buildings that survived the Revolution. They taught their children German and used the language in churches for nearly 100 years. Many Palatines married only within the German community until the 19th century.

The Palatines settled on the frontiers of New York province in Kanienkeh ("the land of the flint"), the homeland of the Five Nations of the Iroquois League (becoming the Six Nations when the Tuscarora joined the League in 1722) in what is now upstate New York, and formed a very close relationship with the Iroquois. The American historian David L. Preston described the lives of the Palatine community as being "interwoven" with the Iroquois communities.[54] One Palatine leader said about the relationship of his community with the Haudenosauee that: "We intend to live our lifetime together as brothers".[54] The Haudenosauee taught the Palatines about the best places to gather wild edible nuts, together with roots and berries, and how to grow the "Three Sisters", as the Iroquois called their staple foods of beans, squash and corn.[52] One Palatine leader, Johann Conrad Weiser, had his son live with a Mohawk family for a year in order to provide the Palatines with both an interpreter and a friend who might bridge the gap between the two different communities.[52] The Palatines came from the patriarchal society of Europe, whereas the Haudenosaunee had a matrilineal society, in which clan mothers selected the sachems and the chiefs.

The Haudenosaunee admired the work ethic of the Palatines, and often rented their land to the hard-working immigrants.[52] In their turn, the Palatines taught Haudenosaunee women how to use iron plows and hoes to farm the land, together with how to grow oats and wheat.[52] The Haudenosaunee considered farming to be women's work, as their women planted, cultivated and harvested their crops. They considered the Palatine men to be unmanly because they worked the fields.[citation needed] Additionally, the Palatines brought sheep, cows, and pigs to Kanienkeh.[52] With increased agricultural production and money coming in as rent, the Haudenosaunee began to sell the surplus food to merchants in Albany.[52] Many clan mothers and chiefs, who had grown wealthy enough to live at about the same standard of living as a middle-class family in Europe, abandoned their traditional log houses for European-style houses.[52]

In 1756, one Palatine farmer brought 38,000 beads of black wampum during a trip to Schenectady, which was enough to make dozens upon dozens of wampum belts, which were commonly presented to Indigenous leaders as gifts when being introduced.[54] Preston noted that the purchasing of so much wampum reflected the very close relations the Palatines had with the Iroquois.[54] The Palatines used their metal-working skills to repair weapons that belonged to the Iroquois, built mills that ground corn for the Iroquois to sell to merchants in New York and New France, and their churches were used for Christian Iroquois weddings and baptisms.[55] There were also a number of intermarriages between the two communities.[55] Doxstader, a surname common in some of the rural areas of south-western Germany, is also a common Iroquois surname.[55]

Preston wrote that the popular stereotype of United States frontier relations between white settler colonists and Native Americans as being from two racial worlds that hardly interacted did not apply to the Palatine-Iroquois relationship, writing that the Palatines lived between Iroquois settlements in Kanienkeh, and the two peoples "communicated, drank, worked, worshipped and traded together, negotiated over land use and borders, and conducted their diplomacy separate from the colonial governments".[56] Some Palatines learned to perform the Haudenosaunee condolence ceremony, where condolences were offered to those whose friends and family had died, which was the most important of all Iroquois rituals.[52] The Canadian historian James Paxton wrote the Palatines and Haudenosaunee "visited each other's homes, conducted small-scale trade and socialized in taverns and trading posts".[52]

Unlike the frontier in Pennsylvania and in the Ohio river valley, where English settlers and the Indians had bloodstained relations, leading to hundreds of murders, relations between the Palatine and Indians in Kanienkeh were friendly. Between 1756 and 1774 in the New York frontier, only 5 colonists or British soldiers were killed by Native Americans, while just 6 Natives were killed by soldiers or settlers.[57] The New York frontier had no equivalent to the Paxton Boys, a vigilante group of Scots-Irish settlers on the Pennsylvania frontier who waged a near-genocidal campaign against the Susquehannock Indians in 1763–64, and the news of the killing perpetrated by the Paxton Boys was received with horror by both whites and Indians on the New York frontier.[57]

However, the Iroquois had initially allowed the Palatines to settle in Kanienkeh out of sympathy for their poverty, and expected them to ultimately contribute for being allowed to live on the land when they become wealthier. In a letter to Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Northern Indian Affairs, in 1756, Oneida sachems and clan mothers complained that they had allowed the Palatines to settle in Kanienkeh out of "compassion to their poverty and expected when they could afford it that they would pay us for their land", going on to write now that the Palatines had "grown rich they not only refuse to pay us for our land, but impose on us in everything we have to do with them".[55] Likewise, many Iroquois sachems and clan mothers complained that their young people were too fond of drinking the beer brewed by the Palatines, charging that alcohol was a destructive force in their community.[58]

.jpg/440px-Demi_Turban._Palatine_(Paris,_1801).jpg)

Despite the intentions of the British, the Palatines showed little inclination to fight for the British Crown, and during French and Indian War, tried to maintain neutrality. After the Battle of Fort Bull and the Fall of Fort Oswego to the French, German Flatts and Fort Herkimer become the northern frontier of the British Empire in North America, causing the British Army to rush regiments to the frontier.[59] One Palatine, Hans Josef Herkimer, complained about the British troops in his vicinity in a letter written in broken English to the authorities: "Tieranniece [tyranny] over me they think proper ... Not only Infesting my House and taking my rooms at their pleashure [pleasure] but takes what they think Nesserarie [necessary] of my Effects".[59]

The Palatines sent messages via the Oneida to Quebec City to tell the governor-general of New France, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, of their wish to be neutral while at the same time trading with the French via Indian middlemen.[60] An Oneida Indian passed on a message to Vaudreuil in Quebec City, saying: "We inform you of a message given to us by a Nation that is neither English, nor French nor Indian and inhabits the lands around us ... That Nation has proposed to annex us to itself in order to afford each other mutual help and protection against the English".[53] Vaundreuil in reply stated "I think I know that nation. There is reason to believe they are the Palatines".[53] Another letter sent by the Palatines to Vaudreuil in late 1756 declared that they "looked upon themselves in danger as well as the Six Nations, they are determined to live and die by them & therefore begged the protection of the French".[60]

Vaudreuil informed the Palatines that neutrality was not an option and they could either submit to the King of France or face war.[60] The Palatines tried to stall, causing Vaudreuil to warn them that this "trick will avail nothing; for whenever I think proper, I shall dispatch my warriors to Corlac" (the French name for New York).[53] At one point, the Oneida sent a message to Vaudreuil asking that "not to due [do] them [the Palatines] any hurt as they were no more white people but Oneidas and that their blood was mixed with the Indians".[55] Preston wrote that the letter may have been exaggerating somewhat, but interracial and intercultural sexual relations are known to have occurred on the frontier.[55] The descendants of the Palatine Dutch and Indians were known as Black Dutch.[61]

On 10 November 1757, the Oneida sachem Canaghquiesa warned the Palatines that a force of French and Indigenous combatants were on their way to attack, telling them that their women and children should head for the nearest fort, but Canaghquiesa noted that they "laughed at me and slapping their hands on their Buttucks [buttocks] said they did not value the Enemy".[62] On 12 November 1757, a raiding party of about 200 Mississauga and Canadian Iroquois warriors together with 65 Troupes de la Marine and Canadien militiamen fell on the settlement of German Flatts at about 3:00 am, burning the town down to the ground, killing about 40 Palatines while taking 150 back to New France.[63] One Palatine leader, Johan Jost Petri, writing from his prison in Montreal, complained about how "our people have been taken by the Indians and the French (but for the most part by our own Indians) and by our own fault".[64] Afterwards, a group of Oneida and Tuscaroras came to the ruins of the German Flatts to offer food and shelter for the survivors and to bury the dead.[56] In a letter to Johnson, Canaghquiesa wrote "we have condoled with our Brethren the Germans on the loss of their Friends who have been lately killed and taken by the Enemy ... that Ceremony was over three days ago".[56]

Many Pennsylvania Dutchmen are descendants of Palatines who settled the Pennsylvania Dutch Country.[6] The Pennsylvania Dutch language, spoken by the Amish and Pennsylvania Dutch in the United States, is derived primarily from the Palatine German language which many Mennonite refugees brought to Pennsylvania in the years 1717 to 1732.[65] The only existing Pennsylvania German newspaper, Hiwwe wie Driwwe, was founded in Germany un 1996 in the village of Ober-Olm, which is located close to Mainz, the state capital (and is published bi-annually as a cooperation project with Kutztown University). In the same village one can find the headquarters of the German-Pennsylvanian Association.

Because of the immigration of Palatine refugees in the 18th century, the term "Palatine" became associated with German. "Until the American War of Independence 'Palatine' henceforth was used indiscriminately for all 'emigrants of German tongue'."[66]Many more Palatines from the Rhenish Palatinate emigrated in the course of the 19th century. For a long time in the American Union, "Palatine" meant German American.[67]

Palatine immigrants came to live in big industrial cities such as Germantown, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. Land-searching Palatines moved to the Midwestern States and founded new homes in the fertile regions of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio.[68]

A vast inpouring of Palatines began to come especially in the middle of the 19th century.[69] Johann Heinrich Heinz (1811-1891), the father of Henry John Heinz who founded the H. J. Heinz Company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, emigrated from Kallstadt, Palatinate, to the United States in 1840.

Included are immigrants that came during the Colonial Period between 1708 and 1775 and their immediate family members.