In chemistry, molecular symmetry describes the symmetry present in molecules and the classification of these molecules according to their symmetry. Molecular symmetry is a fundamental concept in chemistry, as it can be used to predict or explain many of a molecule's chemical properties, such as whether or not it has a dipole moment, as well as its allowed spectroscopic transitions. To do this it is necessary to use group theory. This involves classifying the states of the molecule using the irreducible representations from the character table of the symmetry group of the molecule. Symmetry is useful in the study of molecular orbitals, with applications to the Hückel method, to ligand field theory, and to the Woodward-Hoffmann rules. Many university level textbooks on physical chemistry, quantum chemistry, spectroscopy and inorganic chemistry discuss symmetry.[1][2][3][4][5] Another framework on a larger scale is the use of crystal systems to describe crystallographic symmetry in bulk materials.

There are many techniques for determining the symmetry of a given molecule, including X-ray crystallography and various forms of spectroscopy. Spectroscopic notation is based on symmetry considerations.

The point group symmetry of a molecule is defined by the presence or absence of 5 types of symmetry element.

The five symmetry elements have associated with them five types of symmetry operation, which leave the geometry of the molecule indistinguishable from the starting geometry. They are sometimes distinguished from symmetry elements by a caret or circumflex. Thus, Ĉn is the rotation of a molecule around an axis and Ê is the identity operation. A symmetry element can have more than one symmetry operation associated with it. For example, the C4 axis of the square xenon tetrafluoride (XeF4) molecule is associated with two Ĉ4 rotations in opposite directions (90° and 270°), a Ĉ2 rotation (180°) and Ĉ1 (0° or 360°). Because Ĉ1 is equivalent to Ê, Ŝ1 to σ and Ŝ2 to î, all symmetry operations can be classified as either proper or improper rotations.

For linear molecules, either clockwise or counterclockwise rotation about the molecular axis by any angle Φ is a symmetry operation.

The symmetry operations of a molecule (or other object) form a group. In mathematics, a group is a set with a binary operation that satisfies the four properties listed below.

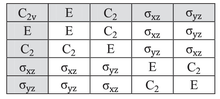

In a symmetry group, the group elements are the symmetry operations (not the symmetry elements), and the binary combination consists of applying first one symmetry operation and then the other. An example is the sequence of a C4 rotation about the z-axis and a reflection in the xy-plane, denoted σ(xy)C4. By convention the order of operations is from right to left.

A symmetry group obeys the defining properties of any group.

The order of a group is the number of elements in the group. For groups of small orders, the group properties can be easily verified by considering its composition table, a table whose rows and columns correspond to elements of the group and whose entries correspond to their products.

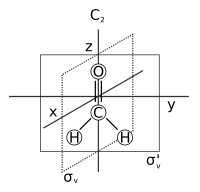

The successive application (or composition) of one or more symmetry operations of a molecule has an effect equivalent to that of some single symmetry operation of the molecule. For example, a C2 rotation followed by a σv reflection is seen to be a σv' symmetry operation: σv*C2 = σv'. ("Operation A followed by B to form C" is written BA = C).[8] Moreover, the set of all symmetry operations (including this composition operation) obeys all the properties of a group, given above. So (S,*) is a group, where S is the set of all symmetry operations of some molecule, and * denotes the composition (repeated application) of symmetry operations.

This group is called the point group of that molecule, because the set of symmetry operations leave at least one point fixed (though for some symmetries an entire axis or an entire plane remains fixed). In other words, a point group is a group that summarises all symmetry operations that all molecules in that category have.[8] The symmetry of a crystal, by contrast, is described by a space group of symmetry operations, which includes translations in space.

One can determine the symmetry operations of the point group for a particular molecule by considering the geometrical symmetry of its molecular model. However, when one uses a point group to classify molecular states, the operations in it are not to be interpreted in the same way. Instead the operations are interpreted as rotating and/or reflecting the vibronic (vibration-electronic) coordinates and these operations commute with the vibronic Hamiltonian. They are "symmetry operations" for that vibronic Hamiltonian. The point group is used to classify by symmetry the vibronic eigenstates of a rigid molecule. The symmetry classification of the rotational levels, the eigenstates of the full (rotation-vibration-electronic) Hamiltonian, can be achieved through the use of the appropriate permutation-inversion group, as introduced by Longuet-Higgins.[9]

Assigning each molecule a point group classifies molecules into categories with similar symmetry properties. For example, PCl3, POF3, XeO3, and NH3 all share identical symmetry operations.[10] They all can undergo the identity operation E, two different C3 rotation operations, and three different σv plane reflections without altering their identities, so they are placed in one point group, C3v, with order 6.[8] Similarly, water (H2O) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) also share identical symmetry operations. They both undergo the identity operation E, one C2 rotation, and two σv reflections without altering their identities, so they are both placed in one point group, C2v, with order 4.[11] This classification system helps scientists to study molecules more efficiently, since chemically related molecules in the same point group tend to exhibit similar bonding schemes, molecular bonding diagrams, and spectroscopic properties.[8]Point group symmetry describes the symmetry of a molecule when fixed at its equilibrium configuration in a particular electronic state. It does not allow for tunneling between minima nor for the change in shape that can come about from the centrifugal distortion effects of molecular rotation.

The following table lists many of the point groups applicable to molecules, labelled using the Schoenflies notation, which is common in chemistry and molecular spectroscopy. The descriptions include common shapes of molecules, which can be explained by the VSEPR model. In each row, the descriptions and examples have no higher symmetries, meaning that the named point group captures all of the point symmetries.

A set of matrices that multiply together in a way that mimics the multiplication table of the elements of a group is called a representation of the group. For example, for the C2v point group, the following three matrices are part of a representation of the group:

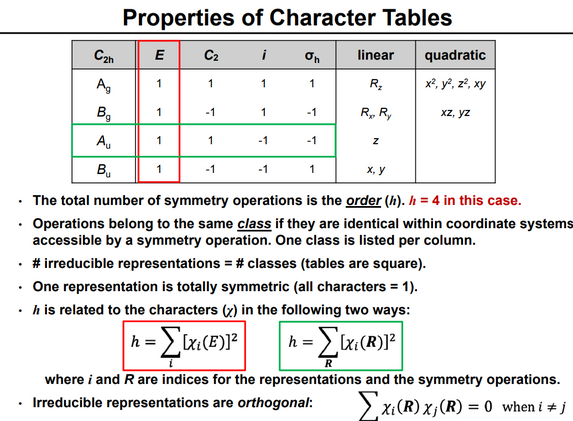

Although an infinite number of such representations exist, the irreducible representations (or "irreps") of the group are all that are needed as all other representations of the group can be described as a direct sum of the irreducible representations. Also, the irreducibile representations are those matrix representations in which the matrices are in their most diagonal form possible.

For any group, its character table gives a tabulation (for the classes of the group) of the characters (the sum of the diagonal elements) of the matrices of all the irreducible representations of the group. As the number of irreducible representations equals the number of classes, the character table is square.

The representations are labeled according to a set of conventions:

The tables also capture information about how the Cartesian basis vectors, rotations about them, and quadratic functions of them transform by the symmetry operations of the group, by noting which irreducible representation transforms in the same way. These indications are conventionally on the righthand side of the tables. This information is useful because chemically important orbitals (in particular p and d orbitals) have the same symmetries as these entities.

The character table for the C2v symmetry point group is given below:

Consider the example of water (H2O), which has the C2v symmetry described above. The 2px orbital of oxygen has B1 symmetry as in the fourth row of the character table above, with x in the sixth column). It is oriented perpendicular to the plane of the molecule and switches sign with a C2 and a σv'(yz) operation, but remains unchanged with the other two operations (obviously, the character for the identity operation is always +1). This orbital's character set is thus {1, −1, 1, −1}, corresponding to the B1 irreducible representation. Likewise, the 2pz orbital is seen to have the symmetry of the A1 irreducible representation (i.e.: none of the symmetry operations change it), 2py B2, and the 3dxy orbital A2. These assignments and others are noted in the rightmost two columns of the table.

Hans Bethe used characters of point group operations in his study of ligand field theory in 1929, and Eugene Wigner used group theory to explain the selection rules of atomic spectroscopy.[14] The first character tables were compiled by László Tisza (1933), in connection to vibrational spectra. Robert Mulliken was the first to publish character tables in English (1933), and E. Bright Wilson used them in 1934 to predict the symmetry of vibrational normal modes.[15] The complete set of 32 crystallographic point groups was published in 1936 by Rosenthal and Murphy.[16]

Each normal mode of molecular vibration has a symmetry which forms a basis for one irreducible representation of the molecular symmetry group.[17] For example, the water molecule has three normal modes of vibration: symmetric stretch in which the two O-H bond lengths vary in phase with each other, asymmetric stretch in which they vary out of phase, and bending in which the bond angle varies. The molecular symmetry of water is C2v with four irreducible representations A1, A2, B1 and B2. The symmetric stretching and the bending modes have symmetry A1, while the asymmetric mode has symmetry B2. The overall symmetry of the three vibrational modes is therefore Γvib = 2A1 + B2.[17][18]

The molecular symmetry of ammonia (NH3) is C3v, with symmetry operations E, C3 and σv.[6] For N = 4 atoms, the number of vibrational modes for a non-linear molecule is 3N-6 = 6, due to the relative motion of the nitrogen atom and the three hydrogen atoms. All three hydrogen atoms travel symmetrically along the N-H bonds, either in the direction of the nitrogen atom or away from it. This mode is known as symmetric stretch (v₁) and reflects the symmetry in the N-H bond stretching. Of the three vibrational modes, this one has the highest frequency.[19]

In the Bending (ν₂) vibration, the nitrogen atom stays on the axis of symmetry, while the three hydrogen atoms move in different directions from one another, leading to changes in the bond angles. The hydrogen atoms move like an umbrella, so this mode is often referred to as the "umbrella mode".[21]

There is also an Asymmetric Stretch mode (ν₃) in which one hydrogen atom approaches the nitrogen atom while the other two hydrogens move away.

The total number of degrees of freedom for each symmetry species (or irreducible representation) can be determined. Ammonia has four atoms, and each atom is associated with three vector components. The symmetry group C3v for NH3 has the three symmetry species A1, A2 and E. The modes of vibration include the vibrational, rotational and translational modes.

Total modes = 3A1 + A2 + 4E. This is a total of 12 modes because each E corresponds to 2 degenerate modes (at the same energy).

Rotational modes = A2 + E (3 modes)

Translational modes = A1 + E

Vibrational modes = Total modes - Rotational modes - Translational modes = 3A1 + A2 + 4E - A2 - E - A1 - E = 2A1 + 2E (6 modes).

Each molecular orbital also has the symmetry of one irreducible representation. For example, ethylene (C2H4) has symmetry group D2h, and its highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is the bonding pi orbital which forms a basis for its irreducible representation B1u.[22]

As discussed above in the section Point groups and permutation-inversion groups, point groups are useful for classifying the vibrational and electronic states of rigid molecules (sometimes called semi-rigid molecules) which undergo only small oscillations about a single equilibrium geometry. Longuet-Higgins introduced a more general type of symmetry group[9] suitable not only for classifying the vibrational and electronic states of rigid molecules but also for classifying their rotational and nuclear spin states. Further, such groups can be used to classify the states of non-rigid (or fluxional) molecules that tunnel between equivalent geometries[23] and to allow for the distorting effects of molecular rotation. These groups are known as permutation-inversion groups, because the symmetry operations in them are energetically feasible permutations of identical nuclei, or inversion with respect to the center of mass (the parity operation), or a combination of the two.[9]

Examples of molecular nonrigidity abound. For example, ethane (C2H6) has three equivalent staggered conformations. Tunneling between the conformations occurs at ordinary temperatures by internal rotation of one methyl group relative to the other. This is not a rotation of the entire molecule about the C3 axis, although each conformation has D3d symmetry, as in the table above. Similarly, ammonia (NH3) has two equivalent pyramidal (C3v) conformations which are interconverted by the process known as nitrogen inversion.

Additionally, the methane (CH4) and H3+ molecules have highly symmetric equilibrium structures with Td and D3h point group symmetries respectively; they lack permanent electric dipole moments but they do have very weak pure rotation spectra because of rotational centrifugal distortion.[24][25]

Sometimes it is necessary to consider together electronic states having different point group symmetries at equilibrium. For example, in its ground (N) electronic state the ethylene molecule C2H4 has D2h point group symmetry whereas in the excited (V) state it has D2d symmetry. To treat these two states together it is necessary to allow torsion and to use the double group of the permutation-inversion group G16.[26]

Each normal mode of vibration will form a basis set for an irreducible representation of the point group of the molecule.