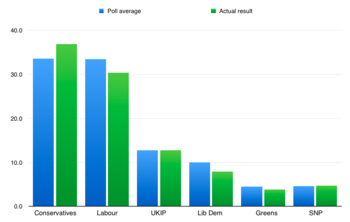

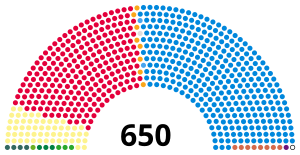

Всеобщие выборы в Соединенном Королевстве 2015 года состоялись в четверг 7 мая 2015 года, чтобы избрать 650 членов парламента (депутатов) в Палату общин . Это были первые из трех всеобщих выборов, проведенных в соответствии с правилами Закона о фиксированном сроке полномочий парламентов 2011 года, и последние всеобщие выборы, проведенные до того, как Соединенное Королевство проголосовало за прекращение своего членства в Европейском союзе (ЕС) в июне 2016 года. Местные выборы прошли в большинстве районов Англии в тот же день и на сегодняшний день являются последними всеобщими выборами, совпадающими с местными выборами. Правящая Консервативная партия во главе с премьер-министром Дэвидом Кэмероном одержала неожиданную победу; опросы общественного мнения и политические комментаторы предсказывали, что результаты выборов приведут ко второму подряд подвешенному парламенту , состав которого будет аналогичен предыдущему парламенту, который действовал с предыдущих национальных выборов в 2010 году . Однако опросы общественного мнения недооценили консерваторов, поскольку они получили 330 из 650 мест и 36,9 процента голосов, что дало им большинство в десять мест.

Оппозиционная Лейбористская партия во главе с Эдом Милибэндом немного увеличила свою долю голосов до 30,4 процента, но она получила на 26 мест меньше, чем в 2010 году. Это дало им 232 депутата. Это было наименьшее количество мест, которое партия получила с всеобщих выборов 1987 года , когда она получила 229 депутатов. Многие высокопоставленные депутаты-лейбористы, включая Эда Боллса , Дугласа Александра и Джима Мерфи , потеряли свои места. Шотландская национальная партия (ШНП) получила 56 из 59 шотландских мест и стала третьей по величине партией в Палате общин, в основном за счет лейбористов, которые имели наибольшее количество мест в Палате общин на каждых всеобщих выборах с 1964 года .

Либеральные демократы во главе с уходящим заместителем премьер-министра Ником Клеггом показали худший результат с момента своего образования в 1988 году, потеряв 49 из 57 мест. Министры кабинета министров Винс Кейбл , Эд Дэйви и Дэнни Александр проиграли перевыборы, в то время как Клегг с трудом сохранил свое место. Партия независимости Великобритании получила 12,6 процента голосов, сместив либеральных демократов с третьей по популярности партии, но выиграла только одно место, Клактон . Лидер партии Найджел Фарадж не смог победить в Саут-Танете . Партия зеленых Англии и Уэльса получила самую высокую долю голосов в 3,8 процента, а их единственный депутат, Кэролайн Лукас , сохранила свое место, Брайтон-Павильон . [3] В Северной Ирландии Ольстерская юнионистская партия вернулась в Палату общин с двумя местами после пятилетнего отсутствия, а Альянсовая партия потеряла свое единственное место в Белфасте-Ист , представленное Наоми Лонг для партии, несмотря на увеличение их доли голосов. После выборов Милибэнд и Клегг оставили свои лидерские позиции. Джереми Корбин сменил Милибэнда на посту лидера Лейбористской партии , в то время как Тим Фаррон сменил Клегга на посту лидера Либеральных демократов .

До выборов 2024 года считалось, что это ознаменовало возвращение к традиционной двухпартийной политике , в которой доминировали консерваторы и лейбористы, которая наблюдалась на протяжении всей второй половины 20-го века; ШНП начала девятилетнее доминирование в шотландской политике . Чарльз Кеннеди , который был лидером либеральных демократов с 1999 по 2006 год, в последний раз появился на публике во время предвыборной кампании, в ходе которой он потерял свое место; он умер 1 июня 2015 года.

Известные депутаты, которые ушли в отставку на этих выборах, включали бывшего премьер-министра Гордона Брауна , бывшего канцлера казначейства Алистера Дарлинга , бывшего лидера Консервативной партии Уильяма Хейга и бывшего лидера либеральных демократов Мензиса Кэмпбелла . Известные новички в Палате общин включали Иэна Блэкфорда , будущего лидера ШНП в Палате общин; Анджелу Рейнер , будущего заместителя премьер-министра и заместителя лидера Лейбористской партии ; Кейра Стармера , будущего премьер-министра и лидера Лейбористской партии; и Риши Сунака , будущего премьер-министра и лидера консерваторов, который сменил Хейга на посту депутата от Ричмонда (Йорк) . Другой будущий премьер-министр-консерватор, Борис Джонсон , который ранее покинул парламент в 2008 году, чтобы занять пост мэра Лондона , вернулся в парламент в качестве депутата от Аксбриджа и Саут-Раислипа .

Закон о парламентах с фиксированным сроком полномочий 2011 года привел к роспуску 55-го парламента 30 марта 2015 года и назначению выборов на 7 мая. [4] Местные выборы прошли в тот же день по всей Англии, за исключением Большого Лондона . В Шотландии, Уэльсе и Северной Ирландии выборы не были запланированы.

Все граждане Великобритании, Ирландии и стран Содружества, достигшие 18 лет и проживающие в Великобритании, которые на дату выборов не находились в тюрьме или психиатрической больнице или не были беглецами, имели право голосовать. На британских всеобщих выборах голосование проводится во всех избирательных округах Соединенного Королевства для избрания членов парламента в Палату общин , нижнюю палату парламента в Великобритании. Каждый избирательный округ избирает одного депутата, используя систему голосования по принципу первого проголосовавшего . Если одна партия получает большинство (326) из 650 мест, то эта партия имеет право сформировать правительство . Если ни одна партия не имеет большинства, то существует так называемый подвешенный парламент . В этом случае вариантами формирования правительства являются либо правительство меньшинства (когда одна партия правит единолично, несмотря на то, что не имеет большинства мест), либо коалиционное правительство (когда одна партия правит вместе с другой партией, чтобы получить большинство мест). [5]

Хотя Консервативная партия планировала сократить количество избирательных округов с 650 до 600 посредством Шестого периодического обзора избирательных округов Вестминстера в соответствии с Законом о парламентской избирательной системе и избирательных округах 2011 года , обзор избирательных округов и сокращение мест были отложены Законом о регистрации и администрировании выборов 2013 года . [6] [7] [8] [9] Следующий обзор границ был назначен на 2018 год, поэтому всеобщие выборы 2015 года проводились с использованием тех же избирательных округов и границ, что и в 2010 году. Из 650 избирательных округов 533 находились в Англии, 59 — в Шотландии, 40 — в Уэльсе и 18 — в Северной Ирландии.

Кроме того, Закон 2011 года предписывал провести референдум в 2011 году по вопросу изменения системы голосования с большинством голосов на альтернативную систему голосования для всеобщих выборов. Коалиционное правительство консерваторов и либеральных демократов согласилось провести референдум. [10] Референдум состоялся в мае 2011 года и привел к сохранению существующей системы голосования. Перед предыдущими всеобщими выборами либеральные демократы пообещали изменить систему голосования, а лейбористская партия пообещала провести референдум по любому такому изменению. [11] Консерваторы, однако, пообещали сохранить систему большинства, но сократить количество избирательных округов до 600. План либеральных демократов состоял в том, чтобы сократить количество депутатов до 500 и избирать их с использованием пропорциональной системы голосования . [12] [13]

Правительство увеличило сумму денег, которую партиям и кандидатам было разрешено тратить на агитацию во время выборов, на 23%, что было принято вопреки рекомендациям Избирательной комиссии . [14] На выборах впервые был установлен предел расходов партий в отдельных избирательных округах в течение 100 дней до роспуска парламента 30 марта: £30 700, плюс надбавка на одного избирателя в размере 9 пенсов в окружных избирательных округах и 6 пенсов в городских округах. Дополнительная надбавка на избирателя в размере более £8 700 доступна после роспуска парламента. В общей сложности партии потратили £31,1 млн на всеобщих выборах 2010 года, из которых Консервативная партия потратила 53%, Лейбористская партия потратила 25% и Либеральные демократы 15%. [15] Это были также первые всеобщие выборы в Великобритании, на которых использовалась индивидуальная, а не домохозяйственная регистрация избирателей .

Выборы назначаются после роспуска парламента Соединенного Королевства . Всеобщие выборы 2015 года были первыми, проведенными в соответствии с положениями Закона о фиксированном сроке полномочий парламента 2011 года . До этого право распускать парламент было королевской прерогативой , осуществляемой сувереном по совету премьер-министра. Согласно положениям Закона о семилетии 1715 года , измененного Законом о парламенте 1911 года , выборы должны были быть объявлены не позднее пятой годовщины начала работы предыдущего парламента, за исключением исключительных обстоятельств. Ни один суверен не отклонял просьбу о роспуске с начала 20-го века, и практика развивалась так, что премьер-министр обычно назначал всеобщие выборы, которые проводились в тактически удобное время в течение последних двух лет срока полномочий парламента, чтобы максимизировать шансы на победу на выборах для своей партии. [16]

Перед всеобщими выборами 2010 года лейбористы и либеральные демократы пообещали ввести выборы с фиксированным сроком полномочий . [11] В рамках соглашения о коалиции консерваторов и либеральных демократов министерство Кэмерона согласилось поддержать законодательство о парламентах с фиксированным сроком полномочий, при этом дата следующих всеобщих выборов была назначена на 7 мая 2015 года. [17] Это привело к принятию Закона о парламентах с фиксированным сроком полномочий 2011 года, который лишил премьер-министра полномочий рекомендовать монарху назначить досрочные выборы. Закон допускает досрочный роспуск только в том случае, если парламент проголосует за него двумя третями квалифицированного большинства или если большинство депутатов примет вотум недоверия и в течение 14 дней не будет сформировано новое правительство. [18] Однако премьер-министр имел полномочия, согласно распоряжению, изданному статутным актом в соответствии с разделом 1(5) Закона о парламентах с фиксированным сроком полномочий 2011 года, назначить день голосования на два месяца позже 7 мая 2015 года. Такой статутный акт должен быть одобрен каждой палатой парламента. Согласно разделу 14 Закона о регистрации и администрировании выборов 2013 года , в Закон о парламентах с фиксированным сроком полномочий 2011 года были внесены поправки, чтобы продлить период между роспуском парламента и следующим днем голосования на всеобщих выборах с 17 до 25 рабочих дней. Это имело эффект переноса даты роспуска парламента на 30 марта 2015 года. [4]

Ключевые даты:

В то время как на предыдущих выборах было рекордное количество депутатов — 149, не баллотировавшихся на переизбрание, [20] на выборах 2015 года 89 депутатов покинули свои посты. [21] Из этих депутатов 37 были консерваторами, 37 — лейбористами, 10 — либеральными демократами, 3 — независимыми, 1 — Шинн Фейн и 1 — Плайд Камри. Самыми известными членами парламента, покинувшими свой пост, были: Гордон Браун , бывший премьер-министр, и Уильям Хейг , бывший лидер Консервативной партии и лидер оппозиции . [22] Наряду с Брауном и Хейгом, на выборах покинули свои посты 17 бывших министров кабинета, в том числе Стивен Доррелл , Джек Стро , Алистер Дарлинг , Дэвид Бланкетт , сэр Малкольм Рифкинд и дама Тесса Джоуэлл . [22] Самым известным либеральным демократом, ушедшим в отставку, был их бывший лидер сэр Мензис Кэмпбелл , в то время как старейший депутат сэр Питер Тэпселл также вышел в отставку, проработав депутатом непрерывно с 1966 года , или в течение 49 лет. [22]

На 9 апреля 2015 года, в крайний срок для участия во всеобщих выборах, Избирательной комиссией было зарегистрировано 464 политические партии . Кандидаты, не принадлежавшие ни к одной партии, либо были помечены как независимые , либо не были помечены вообще.

Консервативная партия и Лейбористская партия были двумя крупнейшими партиями с 1922 года . Каждый премьер-министр, занимавший этот пост с 1935 года, был лидером консерваторов или лейбористов. Опросы общественного мнения предсказывали, что обе партии получат в общей сложности от 65% до 75% голосов и получат от 80% до 85% мест; [23] [24] и что, таким образом, лидер одной из двух партий станет премьер-министром ( Дэвид Кэмерон от консерваторов или Эд Милибэнд от лейбористов) после выборов. Либеральные демократы были третьей по величине партией в Великобритании в течение многих лет; но, как описывают различные политические комментаторы, другие партии выросли относительно либеральных демократов после выборов 2010 года. [25] [26] Чтобы подчеркнуть это, The Economist заявил, что «знакомая трехпартийная система тори, лейбористов и либерал-демократов, похоже, рушится с ростом UKIP, зеленых и SNP». Ofcom постановил, что основными партиями в Великобритании являются консерваторы, лейбористы, либерал-демократы и UKIP, SNP — крупная партия в Шотландии, а Plaid Cymru — крупная партия в Уэльсе. [27] Руководящие принципы BBC были похожи, но UKIP была исключена из списка основных партий, и вместо этого было заявлено, что UKIP следует предоставить «соответствующие уровни освещения в выпуске, в который вносят вклад крупнейшие партии, а в некоторых случаях — аналогичные уровни освещения». [28] [29] В дебатах о лидерстве на выборах приняли участие семь партий : консерваторы, лейбористы, либерал-демократы, UKIP, SNP, ПК и зеленые. [30] Политические партии Северной Ирландии не были включены ни в какие дебаты, несмотря на то, что Демократическая юнионистская партия , партия, базирующаяся в Северной Ирландии, была четвертой по величине партией в Великобритании, готовящейся к выборам.

.jpg/440px-David_Cameron_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg/440px-The_Rt_Hon_Nick_Clegg,_Deputy_Prime_Minister,_UK_(8144405296).jpg)

Несколько партий действуют только в определенных регионах. Основные национальные партии, занимающие большинство мест по всей стране, перечислены ниже в порядке количества мест, за которые они боролись:

Десятки мелких партий участвовали в этих выборах. Коалиция профсоюзных деятелей и социалистов выдвинула 135 кандидатов и была единственной мелкой партией, у которой было более сорока кандидатов. [31] Партия «Уважение» , которая пришла на выборы с одним депутатом , избранным на дополнительных выборах в Брэдфорд-Уэсте в 2012 году , выдвинула четырех кандидатов. Британская национальная партия , которая заняла пятое место с 1,9% голосов и выдвинула 338 кандидатов на всеобщих выборах 2010 года, выдвинула только восемь кандидатов в этом году после провала их поддержки. [32] На всеобщих выборах баллотировались еще семьсот пятьдесят три кандидата, включая независимых и кандидатов от других партий. [32]

Основные партии Северной Ирландии в порядке убывания количества мест:

Менее крупные партии в Северной Ирландии включали « Голос традиционных юнионистов» , который не получил мест на этих выборах, но имел одного члена в Ассамблее Северной Ирландии, консерваторов и UKIP (обе являются основными партиями в остальной части Великобритании, но здесь они второстепенные). [35]

К мелким партиям в Шотландии относится Шотландская либертарианская партия , но ни одна из мелких партий не оказывает существенного влияния на всеобщие выборы в Шотландии.

В Уэльсе есть ряд небольших партий, которые, опять же, не оказывают большого влияния на всеобщие выборы. В 2015 году Лейбористская партия продолжала доминировать в политике Уэльса на всеобщих выборах.

Коалиции были редки в Соединенном Королевстве, поскольку система голосования по мажоритарной системе обычно приводила к тому, что одна партия получала абсолютное большинство в Палате общин. Однако, поскольку уходящее правительство было коалиционным, а опросы общественного мнения не показывали значительного или постоянного преимущества какой-либо одной партии, было много дискуссий о возможных послевыборных коалициях или других соглашениях, таких как соглашения о доверии и поставках . [37]

Некоторые политические партии Великобритании, которые представлены только в части страны, имеют взаимные отношения с партиями, представленными в других частях страны. К ним относятся:

17 марта 2015 года Демократическая юнионистская партия и Ольстерская юнионистская партия договорились о предвыборном пакте, в соответствии с которым DUP не будет выдвигать кандидатов в Фермане и Южном Тироне (где Мишель Гилдернью , кандидат от Sinn Féin , победила всего на четыре голоса в 2010 году), а также в Ньюри и Арме . Взамен UUP останется в стороне в Белфасте-Восточном и Белфасте-Северном . SDLP отклонила аналогичный пакт, предложенный Sinn Féin, чтобы попытаться гарантировать, что согласованный националист победит в этом округе. [41] [42] [43] DUP также призвала избирателей в Шотландии поддержать любого про-юнионистского кандидата, который будет лучше всего подготовлен к победе над SNP. [44]

Крайний срок подачи документов о выдвижении кандидатов партиями и отдельными лицами исполняющему обязанности должностного лица по выборам (и крайний срок для кандидатов снять свои кандидатуры) был 16:00 9 апреля 2015 года. [45] [46] [47] [48] Общее количество кандидатов составило 3971; второе по величине число в истории, немного ниже рекордных 4150 кандидатов на последних выборах в 2010 году. [32] [49]

Было рекордное количество женщин-кандидатов, баллотирующихся как по абсолютным числам, так и по процентному соотношению кандидатов: 1020 (26,1%) в 2015 году, по сравнению с 854 (21,1%) в 2010 году. [32] [49] Доля женщин-кандидатов от основных партий варьировалась от 41% кандидатов от Альянсовой партии до 12% кандидатов от UKIP. [50] Согласно проекту UCL «Кандидаты в парламент Великобритании» [51], основные партии имели следующие проценты чернокожих кандидатов и кандидатов из числа этнических меньшинств: консерваторы 11%, либерал-демократы 10%, лейбористы 9%, UKIP 6%, зеленые 4%. [52] Средний возраст кандидатов от семи основных партий составлял 45 лет. [51]

Самым молодым кандидатам было по 18 лет: Соломон Кертис (лейбористская партия, Уилден ); Ниам Маккарти (независимый кандидат, Ливерпуль Уэвертри ); Майкл Берроуз (UKIP, Инверклайд ); Деклан Ллойд (лейбористская партия, Юго-Восточный Корнуолл ); и Лора-Джейн Россингтон ( коммунистическая партия , Плимут Саттон и Девонпорт ). [53] [54] [55] Самым старым кандидатом была Дорис Озен, 84 года, из Независимой партии пожилых людей (EPIC), которая баллотировалась в Илфорд-Норт . [54] Среди других кандидатов в возрасте старше 80 лет были три давних члена парламента от лейбористской партии, баллотировавшихся на переизбрание: сэр Джеральд Кауфман (84 года; Манчестер Гортон ), Деннис Скиннер (83 года; Болсовер ) и Дэвид Уинник (81 год; Уолсолл-Норт ). После своего переизбрания Кауфман стал Отцом Палаты представителей , и этот почетный титул он носил до своей смерти в начале 2017 года.

Несколько кандидатов, включая двух от Лейбористской партии [56] [57] и UKIP, [58] [59] были отстранены от своих партий после закрытия номинаций. Независимый кандидат Ронни Кэрролл умер после закрытия номинаций. [60]

В конце 2014 года, за год до выборов, консерваторы решили нацелиться на места либерал-демократов, а также на защиту своих собственных мест и нацелиться на маргиналов консерваторов и лейбористов, что в конечном итоге способствовало их победе. [61] В 2015 году Дэвид Кэмерон начал официальную кампанию консерваторов в Чиппенхэме 30 марта. [62] На протяжении всей кампании консерваторы играли на страхах коалиции лейбористов и ШНП после референдума о независимости Шотландии годом ранее. [63]

Лейбористская кампания стартовала 27 марта в Олимпийском парке в Лондоне . [64] [65] EdStone Эда Милибэнда был главной особенностью кампании, которая освещалась средствами массовой информации. [66] Заместитель лидера Лейбористской партии Харриет Харман отправилась в розовую автобусную экскурсию в рамках своей кампании «Женщина женщине» . [67]

Консервативный манифест обязывался провести «прямой референдум о нашем членстве в Европейском союзе к концу 2017 года». [68] Лейбористы это не поддержали, но обязались провести референдум о членстве в ЕС, если какие-либо дополнительные полномочия будут переданы Европейскому союзу. [69] Либеральные демократы также поддержали позицию лейбористов, но открыто поддержали сохранение членства Великобритании в ЕС.

Выборы были первыми после референдума о независимости Шотландии 2014 года . Ни один из трех основных партийных манифестов не поддерживал второй референдум, а в манифесте консерваторов говорилось, что «вопрос о месте Шотландии в Соединенном Королевстве теперь решен». В преддверии выборов Дэвид Кэмерон придумал фразу «принцип Карлайла» для идеи о том, что необходимы сдержки и противовесы для обеспечения того, чтобы передача полномочий Шотландии не имела неблагоприятных последствий для других частей Соединенного Королевства. [70] [71] Фраза ссылается на опасения, что Карлайл , будучи английским городом, ближайшим к шотландской границе, может пострадать экономически из-за льготных налоговых ставок в Шотландии .

Дефицит, кто за него отвечает и планы по его преодолению были главной темой кампании. В то время как некоторые более мелкие партии выступали против жесткой экономии, [72] консерваторы, лейбористы, либеральные демократы, UKIP и зеленые поддержали некоторые дальнейшие сокращения, хотя и в разной степени.

Консервативная агитация стремилась возложить вину за дефицит на предыдущее лейбористское правительство. Лейбористы, в свою очередь, стремились установить свою фискальную ответственность. Поскольку консерваторы также взяли на себя несколько обязательств по расходам (например, на NHS), комментаторы говорили о «политическом переодевании» двух основных партий, каждая из которых пыталась вести агитацию на традиционной территории другой. [73]

Подвешенные парламенты были необычным явлением в британской политической истории со времен Второй мировой войны , но с уходящим правительством, представляющим собой коалицию, и с опросами общественного мнения, не показывающими значительного или последовательного преимущества какой-либо одной партии, многие ожидали и предсказывали на протяжении всей предвыборной кампании, что ни одна партия не получит абсолютного большинства, что могло бы привести к созданию новой коалиции или другим соглашениям, таким как соглашения о доверии и поставках . [74] [75] Это также было связано с ростом многопартийной политики, с возросшей поддержкой UKIP, SNP и Greens.

Британия стоит перед простым и неизбежным выбором – стабильность и сильное правительство со мной или хаос с Эдом Милибэндом: https://facebook.com/DavidCameronOfficial/posts/979082725449379

4 мая 2015 г. [76]

Вопрос о том, что будут делать разные партии в случае подвешенного результата, доминировал в большей части кампании. Менее крупные партии сосредоточились на силе, которую это им даст на переговорах; лейбористы и консерваторы настаивали на том, что они работают над получением правительства большинства, в то же время сообщалось, что они готовятся к возможности проведения вторых выборов в этом году. [77] На практике лейбористы были готовы сделать «широкое» предложение либеральным демократам в случае подвешенного парламента. [78] Большинство прогнозов рассматривали лейбористов как имеющих большую потенциальную поддержку в парламенте, чем консерваторы, при этом несколько партий, в частности ШНП, обязались не допустить появления консервативного правительства. [79] [80] Консерваторы описали потенциальный подвешенный парламент во главе с лейбористами как «коалицию хаоса», а Дэвид Кэмерон описал (в твите ) избирательный выбор как один между « стабильным и сильным правительством со мной или хаосом с Эдом Милибэндом ». [81] [82] Политические потрясения в Великобритании после выборов 2015 года сделали этот твит «печально известным». [82]

Консервативная агитация стремилась подчеркнуть то, что они описали как опасности администрации лейбористов меньшинства, поддерживаемой ШНП. Это оказалось эффективным для доминирования повестки дня кампании [78] и мотивации избирателей поддержать их. [83] [84] [85] [86] Победа консерваторов была «широко приписана успеху антилейбористских/ШНП предупреждений», согласно статье BBC [87] и другим. [88] Лейбористы, в ответ, стали все более решительно отрицать, что они будут сотрудничать с ШНП после выборов. [78] Консерваторы и либерал-демократы также отвергли идею коалиции с ШНП. [89] [90] [91] Это было особенно заметно для лейбористов, которым ШНП ранее предлагала поддержку: в их манифесте говорилось, что «ШНП никогда не приведет тори к власти. Вместо этого, если после выборов будет антиториское большинство, мы предложим работать с другими партиями, чтобы не допустить тори». [92] [93] Лидер ШНП Никола Стерджен позже подтвердила в дебатах шотландских лидеров на STV , что она готова «помочь сделать Эда Милибэнда премьер-министром». [94] Однако 26 апреля Милибэнд исключил возможность заключения соглашения о доверии и поставках также и с ШНП. [95] Комментарии Милибэнда намекали многим, что он работает над формированием правительства меньшинства. [96] [97]

Либеральные демократы заявили, что сначала они будут говорить с той партией, которая получит больше всего мест. [98] Позже они проводили кампанию за то, чтобы оказать стабилизирующее влияние, если консерваторы или лейбористы не получат большинства, с лозунгом «Мы принесем сердце консервативному правительству и мозг лейбористскому». [99]

Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats ruled out coalitions with UKIP.[100] Ruth Davidson, leader of the Scottish Conservatives, asked about a deal with UKIP in the Scottish leaders' debate, replied: "No deals with UKIP." She continued that her preference and the Prime Minister's preference in a hung Parliament was for a minority Conservative government.[101] UKIP said they could have supported a minority Conservative government through a confidence and supply arrangement in return for a referendum on EU membership before Christmas 2015.[102] They also spoke of the DUP joining UKIP in this arrangement.[103] UKIP and DUP said they would work together in Parliament.[104] The DUP welcomed the possibility of a hung Parliament and the influence that this would bring them.[77] The party's deputy leader, Nigel Dodds, said the party could work with the Conservatives or Labour, but that the party is "not interested in a full-blown coalition government".[105] Their leader, Peter Robinson, said that the DUP would talk first to whichever party wins the most seats.[106] The DUP said they wanted, for their support, a commitment to 2% defence spending, a referendum on EU membership, and a reversal of the under-occupation penalty. They opposed the SNP being involved in government.[107][108] The UUP also indicated that they would not work with the SNP if it wanted another independence referendum in Scotland.[109]

The then Deputy Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal Democrats, Nick Clegg, warned against this "Blukip" coalition (UKIP, Conservatives and DUP) with a spoof website highlighting imagined policies from this coalition, such as reinstating the death penalty, scrapping all benefits for under-25s and charging for hospital visits.[110] Additionally, issues were raised about the continued existence of the BBC (as the DUP, UKIP and Conservatives had made a number of statements criticising the institution)[111] and support for same-sex marriage.[112][113]

The Green Party of England & Wales, Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party all ruled out working with the Conservatives, and agreed to work together "wherever possible" to counter austerity.[114][115][72] Each would also make it a condition of any agreement with Labour that Trident nuclear weapons were not replaced; the Green Party of England and Wales stated that "austerity is a red line".[116] Both Plaid Cymru and the Green Party stated a preference for a confidence and supply arrangement with Labour, rather than a coalition.[116][117] The leader of the SDLP, Alasdair McDonnell, said: "We will be the left-of-centre backbone of a Labour administration" and that "the SDLP will categorically refuse to support David Cameron and the Conservative Party".[118] Sinn Féin reiterated their abstentionist stance.[77] In the end the Conservatives did secure an overall majority, rendering much of the speculation and positioning moot.

The first series of televised leaders' debates in the United Kingdom was held in the previous election. Returning major party leaders Cameron and Clegg participated, as did then-prime minister Gordon Brown, who did not seek another mandate in his constituency in 2015. Following much debate and various proposals,[119][120] a seven-way debate with the leaders of Labour, the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, UKIP, Greens, SNP and Plaid Cymru was held.[121] with a series of other debates involving some of the parties.

The campaign was notable for a reduction in the number of party posters on roadside hoardings. It was suggested that 2015 saw "the death of the campaign poster".[122]

Various newspapers, organisations and individuals endorsed parties or individual candidates for the election. For example, the main national newspapers gave the following endorsements:

Despite speculation that the 2015 general election would be the 'social media election', traditional media, particularly broadcast media, remained more influential than new digital platforms.[123][124][125] A majority of the public (62%) reported that TV coverage had been most influential for informing them during the election period, especially televised debates between politicians.[126] Newspapers were next most influential, with the Daily Mail influencing people's opinions most (30%), followed by The Guardian (21%) and The Times (20%).[126] Online, major media outlets—like BBC News, newspaper websites, and Sky News—were most influential.[126] Social media was regarded less influential than radio and conversations with friends and family.[126]

During the campaign, TV news coverage was dominated by horse race journalism, focusing on the how close Labour and the Conservatives (supposedly) were according to the polls, and speculation on possible coalition outcomes.[127] This 'meta-coverage' was seen to squeeze out other content, namely policy.[127][128][129] Policy received less than half of election news airtime across all five main TV broadcasters (BBC, ITV, Channel 4, Channel 5, and Sky) during the first five weeks of the campaign.[127] When policy was addressed, the news agenda in both broadcast and print media followed the lead of the Conservative campaign,[128][130][131][132] focusing on the economy, tax, and constitutional matters (e.g., the possibility of a Labour-SNP coalition government),[132][130] with the economy dominating the news every week of the campaign.[131] On TV, these topics made up 43% of all election news coverage;[132] within the papers, nearly a third (31%) of all election-related articles were on the economy alone.[133] Within reporting and comment about the economy, newspapers prioritised the Conservative Party's angles (i.e., spending cuts (1,351 articles), economic growth (921 articles), reducing the deficit (675 articles)) over Labour's (i.e., Zero-hour contracts (445 articles), mansion tax (339 articles), non-domicile status (322 articles)).[133] Less attention was given to policy areas that might have been problematic for the Conservatives, like the NHS or housing (policy topics favoured by Labour)[132] or immigration (favoured by the UK Independence Party).[130]

Reflecting on analysis carried out during the election campaign period, David Deacon of Loughborough University's Communication Research Centre said there was "aggressive partisanship [in] many section of the national press" which could be seen especially in the "Tory press".[128] Similarly, Steve Barnett, Professor of Communications at the University of Westminster, said that, while partisanship has always been part of British newspaper campaigning, in this election it was "more relentless and more one-sided" in favour of the Conservatives and against Labour and the other parties.[125] According to Bart Cammaerts of the Media and Communications Department at the London School of Economics, during the campaign "almost all newspapers were extremely pro-Conservative and rabidly anti-Labour".[134] 57.5% of the daily newspapers backed the Conservatives, 11.7% Labour, 4.9% UKIP, and 1.4% backed a continuation of the incumbent Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government;[135] 66% of Sunday national newspapers backed the Conservatives.[136] Of newspaper front-page lead stories, the Conservatives received 80 positive splashes and 26 negative; Labour received 30 positive against 69 negative.[131] Print media was hostile towards Labour at levels "not seen since the 1992 General Election",[130][134][137][138] when Neil Kinnock was "attacked hard and hit below the belt repeatedly".[134] Roy Greenslade described the newspaper coverage of Labour as "relentless ridicule".[139] Of the leader columns in The Sun 95% were anti-Labour.[138] The SNP also received substantial negative press in English newspapers: of the 59 leader columns about the SNP during the election, one was positive.[131] The Daily Mail ran a headline suggesting SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon was "the most dangerous woman in Britain"[130][140] and, at other times, called her a "glamorous power-dressing imperatrix" and said that she "would make Hillary Clinton look human".[133] While the Scottish edition of The Sun encouraged people north of the border to vote for the SNP, the English edition encouraged people to vote for the Conservatives in order to "stop the SNP running the country".[141] The negative coverage of the SNP increased towards the end of the election campaign.[124] While TV news airtime given to quotations from politicians was more balanced between the two larger parties (Con.: 30.14%; Lab.: 27.98%), more column space in newspapers was dedicated to quotes from Conservative politicians (44.45% versus 29.01% for Labour)[124]—according to analysts, the Conservatives "benefitted from a Tory supporting press in away the other leaders did not".[124] At times, the Conservatives worked closely with newspapers to co-ordinate their news coverage.[133] For example, The Daily Telegraph printed a letter purportedly sent directly to the paper from 5,000 small business owners; the letter had been organised by the Conservatives and prepared at Conservative Campaign Headquarters.[133]

According to researchers at Cardiff University and Loughborough University, TV news agendas focused on Conservative campaign issues partly because of editorial choices to report on news originally broken in the right press but not that broken in the left press.[132][128][127] Researchers also found that the most airtime was given to Conservative politicians, especially in Channel 4's and Channel 5's news coverage, where they received more than a third of speaking time.[127][142] Only ITV gave more airtime to Labour spokespeople (26.9% compared with 25.1% for the Conservatives).[142] Airtime given to the two main political leaders, Cameron (22.4%) and Miliband (20.9%), was more balanced than that given to their parties.[142]

Smaller parties—especially the SNP[142]—received unprecedented levels of media coverage because of speculation about a minority or coalition government.[130][132] The five most prominent politicians were David Cameron (Con) (15% of TV and press appearances), Ed Miliband (Lab) (14.7%), Nick Clegg (Lib Dem) (6.5%), Nicola Sturgeon (SNP) (5.7%), and Nigel Farage (UKIP) (5.5%).[130][132] However, according to analysts from Loughborough University Communication Research Centre, "the big winners of the media coverage were the Conservatives. They gained the most quotation time, the most strident press support, and coverage focused on their favoured issues (the economy and taxation, rather than say the NHS)".[124]

Other than politicians, 'business sources' were the most frequently quoted in the media. On the other hand, trade union representatives, for example, received very little coverage, with business representatives receiving seven times more coverage than unions.[128] Former prime minister Tony Blair was also in the top ten most prominent politicians (=9), warning people about the threat of the UK leaving the EU.[130]

Throughout the 55th parliament of the United Kingdom, first and second place in the polls without exception alternated between the Conservatives and Labour. Labour took a lead in the polls at the end of 2010, driven in part by a collapse in Liberal Democrat support.[143] This lead rose to approximately 10 points over the Conservative Party during 2012, whose ratings dipped alongside an increase in UKIP support.[144] UKIP passed the Liberal Democrats as the third-most popular party at the start of 2013. Following this, Labour's lead over the Conservatives began to fall as UKIP gained support from it as well,[145] and by the end of the year Labour were polling at 39%, compared to 33% for the Conservative Party and 11% for UKIP.[145]

UKIP received 26.6% of the vote at the European elections in 2014, and though their support in the polls for Westminster never reached this level, it did rise up to over 15% through that year.[146] 2014 was also marked by the Scottish independence referendum. Despite the 'No' vote winning, support for the Scottish National Party rose quickly after the referendum, and had reached 43% in Scotland by the end of the year, up 23 points from the 2010 general election, largely at the expense of Labour (−16 points in Scotland) and the Liberal Democrats (−13 points).[147] In Wales, where polls were less frequent, the 2012–2014 period saw a smaller decline in Labour's lead over the second-placed Conservative Party, from 28 points to 17.[148] These votes went mainly to UKIP (+8 points) and Plaid Cymru (+2 points). The rise of UKIP and SNP, alongside the smaller increases for Plaid Cymru and the Green Party (from around 2% to 6%)[146] saw the combined support of the Conservative and Labour party fall to a record low of around 65%.[149] Within this the decline came predominantly from Labour, whose lead fell to under 2 points by the end of 2014.[146] Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrat vote, which had held at about 10% since late 2010, declined further to about 8%.[146]

Early 2015 saw the Labour lead continue to fall, disappearing by the start of March.[150] Polling during the election campaign itself remained relatively static, with the Labour and Conservative parties both polling between 33 and 34% and neither able to establish a consistent lead.[151] Support for the Green Party and UKIP showed slight drops of around 1–2 points each, while Liberal Democrat support rose up to around 9%.[152] In Scotland, support for the SNP continued to grow with polling figures in late March reaching 54%, with the Labour vote continuing to decline accordingly,[153] while Labour retained their (reduced) lead in Wales, polling at 39% by the end of the campaign, to 26% for the Conservatives, 13% for Plaid Cymru, 12% for UKIP and 6% for the Liberal Democrats.[148] The final polls showed a mixture of Conservative leads, Labour leads and ties with both between 31 and 36%, UKIP on 11–16%, the Lib Dems on 8–10%, the Greens on 4–6%, and the SNP on 4–5% of the national vote.[154]

In addition to the national polls, Michael Ashcroft funded from May 2014 a series of polls in marginal constituencies, and constituencies where minor parties were expected to be significant challengers. Among other results, Ashcroft's polls suggested that the growth in SNP support would translate into more than 50 seats;[155] that there was little overall pattern in Labour and Conservative Party marginals;[156] that the Green Party MP Caroline Lucas would retain her seat;[157] that both Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg and UKIP leader Nigel Farage would face very close races to be elected in their own constituencies;[158] and that Liberal Democrat MPs would enjoy an incumbency effect that would lose fewer MPs than their national polling implied.[159] As with other smaller parties, their proportion of MPs remained likely to be considerably lower than that of total, national votes cast. Several polling companies included Ashcroft's polls in their election predictions, though several of the political parties disputed his findings.[160]

The first-past-the-post system used in UK general elections means that the number of seats won is not closely related to vote share.[161] Thus, several approaches were used to convert polling data and other information into seat predictions. The table below lists some of the predictions. ElectionForecast was used by Newsnight and FiveThirtyEight. May2015.com is a project run by the New Statesman magazine.[162]

Seat predictions draw from nationwide polling, polling in the constituent nations of Britain and may additionally incorporate constituency level polling, particularly the Ashcroft polls. Approaches may or may not use uniform national swing (UNS). Approaches may just use current polling, i.e. a "nowcast" (e.g. Electoral Calculus, May2015.com and The Guardian), or add in a predictive element about how polling shifts based on historical data (e.g. ElectionForecast and Elections Etc.).[163] An alternative approach is to use the wisdom of the crowd and base a prediction on betting activity: the Spreadex and Sporting Index columns below cover bets on the number of seats each party will win with the midpoint between asking and selling price, while FirstPastThePost.net aggregates the betting predictions in each individual constituency. Some predictions cover Northern Ireland, with its distinct political culture, while others do not. Parties are sorted by current number of seats in the House of Commons:

Other predictions were published.[177] An election forecasting conference on 27 March 2015 yielded 11 forecasts of the result in Great Britain (including some included in the table above).[178] Averaging the conference predictions gives Labour 283 seats, Conservatives 279, Liberal Democrats 23, UKIP 3, SNP 41, Plaid Cymru 3 and Greens 1.[179] In that situation, no two parties (excluding a Lab-Con coalition) would have been able to form a majority without the support of a third. On 27 April, Rory Scott of the bookmaker Paddy Power predicted Conservatives 284, Labour 272, SNP 50, UKIP 3, and Greens 1.[180] LucidTalk for the Belfast Telegraph predicted for Northern Ireland: DUP 9, Sinn Féin 5, SDLP 3, Sylvia Hermon 1, with the only seat change being the DUP gaining Belfast East from Alliance.[181][182]

An exit poll, collected by Ipsos MORI and GfK on behalf of the BBC, ITN and Sky News, was published at 10 pm at the end of voting. It interviewed around 22,000 people across a sample of 133 constituencies:[198]

This predicted the Conservatives to be 10 seats short of an absolute majority, although with the 5 predicted Sinn Féin MPs not taking their seats, it was likely to be enough to govern. (In the event, Michelle Gildernew lost her seat, reducing the number of Sinn Féin MPs to 4.)[199]

The exit poll was markedly different from the pre-election opinion polls,[200] which had been fairly consistent; this led many pundits and MPs to speculate that the exit poll was inaccurate, and that the final result would have the two main parties closer to each other. Former Liberal Democrat leader Paddy Ashdown vowed to "eat his hat" and former Labour "spin doctor" Alastair Campbell promised to "eat his kilt" if the exit poll, which predicted huge losses for their respective parties, was right.[201]

As it turned out, the results were even more favourable to the Conservatives than the poll predicted, with the Conservatives obtaining 330 seats, an absolute majority.[202] Ashdown and Campbell were presented with hat- and kilt-shaped cakes (labelled "eat me") on BBC Question Time on 8 May.[201]

With the eventual outcome in terms of both votes and seats varying substantially from the bulk of opinion polls released in the final months before the election, the polling industry received criticism for their inability to predict what was a surprisingly clear Conservative victory. Several theories have been put forward to explain the inaccuracy of the pollsters. One theory was that there had simply been a very late swing to the Conservatives, with the polling company Survation claiming that 13% of voters made up their minds in the final days and 17% on the day of the election.[203] The company also claimed that a poll they carried out a day before the election gave the Conservatives 37% and Labour 31%, though they said they did not release the poll (commissioned by the Daily Mirror) on the concern that it was too much of an outlier with other poll results.[204]

However, it was reported that pollsters had in fact picked up a late swing to Labour immediately prior to polling day, not the Conservatives.[205] It was reported after the election that private pollsters working for the two largest parties actually gathered more accurate results, with Labour's pollster James Morris claiming that the issue was largely to do with surveying technique.[206] Morris claimed that telephone polls that immediately asked for voting intentions tended to get a high "Don't know" or anti-government reaction, whereas longer telephone conversations conducted by private polls that collected other information such as views on the leaders' performances placed voters in a much better mode to give their true voting intentions.[citation needed] Another theory was the issue of 'shy Tories' not wanting to openly declare their intention to vote Conservative to pollsters.[207] A final theory, put forward after the election, was the 'Lazy Labour' factor, which claimed that Labour voters tend to not vote on polling day whereas Conservative voters have a much higher turnout.[208]

The British Polling Council announced an inquiry into the substantial variance between the opinion polls and the actual election result.[209][210] The inquiry published preliminary findings in January 2016, concluding that "the ways in which polling samples are constructed was the primary cause of the polling miss".[211] Their final report was published in March 2016.[212]

The British Election Study team have suggested that weighting error appears to be the cause.[213]

After all 650 constituencies had been declared, the results were:[214]

The following table shows final election results as reported by BBC News[217] and The Guardian.[218]

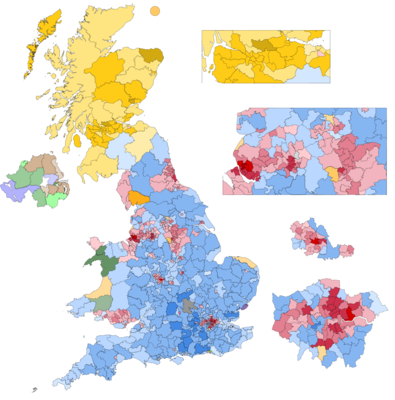

One result of the 2015 general election was that a different political party won the popular vote in each of the countries of the United Kingdom.[220] This was reflected in terms of MPs elected: The Conservatives won in England with 319 MPs out of 533 constituencies,[221] the SNP won in Scotland with 56 out of 59,[222] Labour won in Wales with 25 out of 40,[223] and the Democratic Unionist Party won in Northern Ireland with 8 out of 18.[224]

Despite most opinion polls predicting that the Conservatives and Labour were neck and neck, the Conservatives secured a surprise victory after having won a clear lead over their rivals and incumbent Prime Minister David Cameron was able to form a majority single-party government with a working majority of 12 (in practice increased to 15 due to Sinn Féin's four MPs' abstention). Thus the result bore resemblance to 1992.[225] The Conservatives gained 38 seats while losing 10, all to Labour; Employment Minister Esther McVey, in Wirral West, was the most senior Conservative to lose her seat. Cameron became the first Prime Minister since Lord Salisbury in 1900 to increase his popular vote share after a full term, and is sometimes credited as being the only Prime Minister other than Margaret Thatcher (in 1983) to be re-elected with a greater number of seats for his party after a 'full term'[n 5].[226]

The Labour Party polled below expectations, winning 30.4% of the vote and 232 seats, 24 fewer than its previous result in 2010—even though in 222 constituencies there was a Conservative-to-Labour swing, as against 151 constituencies where there was a Labour-to-Conservative swing.[227] Its net loss of seats were mainly a result of its resounding defeat in Scotland, where the Scottish National Party took 40 of Labour's 41 seats, unseating key politicians such as shadow Foreign Secretary Douglas Alexander and Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy. Labour gained some seats in London and other major cities, but lost a further nine seats to the Conservatives, recording its lowest share of the seats since the 1987 general election.[228] Ed Miliband subsequently tendered his resignation as Labour leader.

The Scottish National Party had a stunning election, rising from just 6 seats to 56 – winning all but 3 of the constituencies in Scotland and securing 50% of the popular vote in Scotland.[222] They recorded a number of record breaking swings of over 30% including the new record of 39.3% in Glasgow North East. They also won the seat of former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, overturning a majority of 23,009 to win by a majority of 9,974 votes and saw Mhairi Black, then a 20-year-old student, defeat Labour's Shadow Foreign Secretary Douglas Alexander with a swing of 26.9%.

The Liberal Democrats, who had been in government as coalition partners, suffered the worst defeat they or the previous Liberal Party had suffered since the 1970 general election.[229] Winning just eight seats, the Liberal Democrats lost their position as the UK's third party and found themselves tied in fourth place with the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland in the House of Commons, with Nick Clegg being one of the few MPs from his party to retain his seat. The Liberal Democrats gained no seats, while losing 49 in the process—of them, 27 to the Conservatives, 12 to Labour, and 10 to the SNP. The party also lost their deposit in 341 seats, the same number as in every general election from 1979 to 2010 combined.

The UK Independence Party (UKIP) was only able to hold one of its two seats, Clacton, gaining no new ones despite increasing its vote share to 12.9% (the third-highest share overall). Party leader Nigel Farage, having failed to win the constituency of South Thanet, tendered his resignation, although this was rejected by his party's executive council and he stayed on as leader.

In Northern Ireland, the Ulster Unionist Party returned to the Commons with two MPs after a five-year absence, gaining one seat from the Democratic Unionist Party and one from Sinn Féin, while the Alliance Party lost its only Commons seat to the DUP, despite an increase in total vote share.[230]

Ipsos MORI polling after the election suggested the following demographic breakdown:

YouGov polling after the election suggested the following demographic breakdown:

The election led to an increase in the number of female MPs, to 191 (29% of the total, including 99 Labour; 68 Conservative; 20 SNP; 4 other) from 147 (23% of the total, including 87 Labour; 47 Conservative; 7 Liberal Democrat; 1 SNP; 5 other). As before the election, the region with the largest proportion of women MPs was North East England.[234]

Votes, of total, by party

MPs, of total, by party

111 seats changed hands compared to the result in 2010 plus three by-election gains reverted to the party that won the seat at the last general election in 2010 (Bradford West, Corby and Rochester and Strood).

On 8 May, three party leaders announced their resignations within an hour of each other:[239] Ed Miliband (Labour) and Nick Clegg (Liberal Democrat) resigned due to their parties' worse-than-expected results in the election, although both had been re-elected to their seats in Parliament.[240][241][242][243] Nigel Farage (UKIP) offered his resignation because he had failed to be elected as MP for Thanet South, but said he might re-stand in the resulting leadership election. However, on 11 May, the UKIP executive rejected his resignation on the grounds that the election campaign had been "a great success",[244] and Farage agreed to continue as party leader.[245]

Alan Sugar, a Labour peer in the House of Lords, also announced his resignation from the Labour Party for running what he perceived to be an anti-business campaign.[246]

In response to Labour's poor performance in Scotland, Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy initially resisted calls for his resignation by other senior party members. Despite surviving a no-confidence vote by 17–14 from the party's national executive, Murphy announced he would step down as leader on or before 16 May.[247]

Financial markets reacted positively to the result, with the pound sterling rising against the Euro and US dollar when the exit poll was published, and the FTSE 100 stock market index rising 2.3% on 8 May. The BBC reported: "Bank shares saw some of the biggest gains, on hopes that the sector will not see any further rises in levies. Shares in Lloyds Banking Group rose 5.75% while Barclays was 3.7% higher", adding: "Energy firms also saw their share prices rise, as Labour had wanted a price freeze and more powers for the energy regulator. British Gas owner Centrica rose 8.1% and SSE shares were up 5.3%." BBC economics editor Robert Peston noted: "To state the obvious, investors love the Tories' general election victory. There are a few reasons. One (no surprise here) is that Labour's threat of breaking up banks and imposing energy price caps has been lifted. Second is that investors have been discounting days and weeks of wrangling after polling day over who would form the government – and so they are semi-euphoric that we already know who's in charge. Third, many investors tend to be economically Conservative and instinctively Conservative."[248]

The disparity between the numbers of votes and the number of seats obtained by the smaller parties gave rise to increased calls for replacement of the 'first-past-the-post' voting system with a more proportional system. For example, UKIP had 3.9 million votes per seat, whereas SNP had just 26,000 votes per seat, about 150 times greater representation for each vote cast. UKIP stood in 10 times as many seats as the SNP. Noting that UKIP's 13% share of the overall votes cast had resulted in the election of just one MP, Nigel Farage argued that the UK's voting system needed reforming, saying: "Personally, I think the first-past-the-post system is bankrupt."[249]

Re-elected Green Party MP Caroline Lucas agreed, saying: "The political system in this country is broken [...] It's ever clearer tonight that the time for electoral reform is long overdue, and it's only proportional representation that will deliver a Parliament that is truly legitimate and better reflects the people it is meant to represent."[250]

Following the election, The Daily Telegraph detailed changes to Wikipedia pages made from computers with IP addresses inside Parliament raising suspicion that "MPs or their political parties deliberately hid information from the public online to make candidates appear more electable to voters" and a deliberate attempt to hide embarrassing information from the electorate.[251]

On 21 December 2015, the UK Information Commissioner's Office fined the Telegraph Media Group £30,000 for sending 'hundreds of thousands of emails on the day of the general election urging readers to vote Conservative ... in a letter from Daily Telegraph editor Chris Evans, attached to the paper's usual morning e-bulletin'. The ICO concluded that subscribers had not expressed their consent to receive this kind of direct marketing.[252]

Four electors from Orkney and Shetland lodged an election petition on 29 May 2015 attempting to unseat Alistair Carmichael and force a by-election[253][254] over what became known as 'Frenchgate'.[255] The issue centred around the leaking of a memo from the Scotland Office about comments allegedly made by the French ambassador Sylvie Bermann about Nicola Sturgeon, claiming that Sturgeon had privately stated she would "rather see David Cameron remain as PM", in contrast to her publicly stated opposition to a Conservative government.[256] The veracity of the memo was quickly denied by the French ambassador, French consul general and Sturgeon.[257] At the time of the leak, Carmichael denied all knowledge of the leaking of the memo in a television interview with Channel 4 News.[258] but after the election Carmichael accepted the contents of the memo were incorrect, admitted that he had lied, and that he had authorised the leaking of the inaccurate memo to the media after a Cabinet Office enquiry identified Carmichael's role in the leak. On 9 December, an Election Court decided that although he had told a "blatant lie" in a TV interview, it had not been proven beyond reasonable doubt that he had committed an "illegal practice" under the Representation of the People Act[259] and he was allowed to retain his seat.[260]

At national party level, the Electoral Commission fined the three largest parties for breaches of spending regulations, levying the highest fines since its foundation:[261] £20,000 for Labour in October 2016,[262] £20,000 for the Liberal Democrats in December 2016,[263] and £70,000 for the Conservative Party in March 2017.[264][261]

The higher fine for the Conservatives reflected both the extent of the wrongdoing (which extended to the 2014 parliamentary by-elections in Clacton, Newark and Rochester and Strood) and 'the unreasonable uncooperative conduct by the Party'.[265][261] The commission also found that the Party Treasurer, Simon Day, may not have fulfilled his obligations under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 and referred him for investigation to the Metropolitan Police Service.[266]

At constituency level, related alleged breaches of spending regulations led to 'unprecedented'[264] police investigations for possible criminal conduct of between 20 and 30 Conservative Party MPs. On 9 May 2017, the Crown Prosecution Service decided not to prosecute the vast majority of suspects, saying that "in order to bring a charge, it must be proved that a suspect knew the return was inaccurate and acted dishonestly in signing the declaration. Although there is evidence to suggest the returns may have been inaccurate, there is insufficient evidence to prove to the criminal standard that any candidate or agent was dishonest."[267] On 2 June 2017, charges were brought under the Representation of the People Act 1983 against Craig Mackinlay, who was elected Conservative MP for South Thanet in 2015, his agent Nathan Gray, and a party activist, Marion Little.[268][269] Appearing at Westminster Magistrates' Court on 4 July 2017, the three pleased not guilty and were released on unconditional bail pending an appearance at Southwark Crown Court on 1 August 2017.[270][271] The investigation of Party Treasurer Simon Day remained ongoing.[272]

In 2016–18, the European Parliament found that UKIP had unlawfully spent over €173,000 of EU funding on the party's 2015 UK election campaign, via the Alliance for Direct Democracy in Europe and the affiliated Institute for Direct Democracy. The Parliament required the repayment of the mis-spent funds and denied the organisations some other funding.[273][274][275] It also found that UKIP MEPs had unlawfully spent EU money on other assistance for national campaigning purposes during 2014–16 and docked their salaries to recoup the mis-spent funds.[276][277][278]