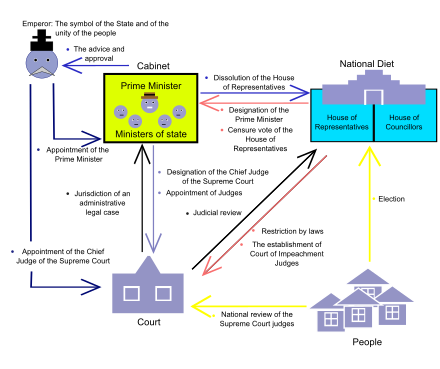

Правительство Японии является центральным правительством Японии . Правительство Японии состоит из законодательной , исполнительной и судебной ветвей власти и основано на народном суверенитете , функционируя в рамках, установленных Конституцией Японии , принятой в 1947 году. Япония является унитарным государством , содержащим сорок семь административных единиц , с императором в качестве главы государства . [1] Его роль церемониальная, и он не имеет полномочий, связанных с правительством. [2] Вместо этого Кабинет , состоящий из государственных министров и премьер-министра , направляет и контролирует правительство и государственную службу . Кабинет имеет исполнительную власть и формируется премьер-министром, который является главой правительства . [3] [4] Премьер-министр назначается Национальным парламентом и назначается на должность Императором. [5] [6]

Национальный парламент является законодательным органом , органом законодательной ветви власти. Парламент двухпалатный , состоящий из двух палат, при этом Палата советников является верхней палатой , а Палата представителей является нижней палатой . Члены обеих палат парламента избираются напрямую народом , который является источником суверенитета . [7] Парламент определяется как высший орган суверенитета в Конституции. Верховный суд и другие низшие суды составляют судебную ветвь власти и обладают всеми судебными полномочиями в государстве. Верховный суд имеет высшие судебные полномочия по толкованию японской конституции и полномочия судебного надзора . Судебная ветвь власти независима от исполнительной и законодательной ветвей власти. [8] Судьи выдвигаются или назначаются Кабинетом министров и никогда не смещаются исполнительной или законодательной властью, за исключением случаев импичмента .

Правительство Японии базируется в столице Токио , где расположены здание Национального парламента , Императорский дворец , Верховный суд, канцелярия премьер-министра и министерства.

До реставрации Мэйдзи Япония управлялась правительством последовательного военного сёгуна . В этот период эффективная власть правительства принадлежала сёгуну, который официально правил страной от имени императора. [9] Сёгуны были наследственными военными губернаторами, их современный ранг эквивалентен генералиссимусу . Хотя император был сувереном, который назначал сёгуна, его роли были церемониальными, и он не принимал участия в управлении страной. [10] Это часто сравнивают с нынешней ролью императора, чья официальная роль заключается в назначении премьер-министра. [11]

Возвращение политической власти императору (императорскому двору) в 1868 году означало отставку сёгуна Токугавы Ёсинобу , который согласился «быть инструментом для выполнения» приказов императора. [12] Это событие восстановило страну под императорским правлением и провозгласило Японскую империю . В 1889 году была принята Конституция Мэйдзи в целях укрепления Японии до уровня западных стран, что привело к появлению первой парламентской системы в Азии. [13] Она предусматривала форму смешанной конституционно - абсолютной монархии ( полуконституционной монархии ) с независимой судебной системой, основанной на прусской модели того времени. [14]

Была создана новая аристократия, известная как кадзоку . Она объединила древнюю придворную знать периода Хэйан , кугэ , и бывших даймё , феодалов, подчиненных сёгуну . [ 15] Она также учредила Императорский парламент , состоящий из Палаты представителей и Палаты пэров . Членами Палаты пэров были члены императорской семьи , кадзоку и те, кого назначал император, [16] в то время как члены Палаты представителей избирались прямым мужским голосованием. [17] Несмотря на четкие различия между полномочиями исполнительной власти и императора в Конституции Мэйдзи, двусмысленность и противоречия в Конституции в конечном итоге привели к политическому кризису . [18] Она также обесценила понятие гражданского контроля над армией , что означало, что военные могли развиваться и оказывать большое влияние на политику. [19]

После окончания Второй мировой войны была принята нынешняя Конституция Японии . Она заменила предыдущее императорское правление формой либеральной демократии западного образца . [20]

По состоянию на 2020 год Японский исследовательский институт обнаружил, что национальное правительство в основном аналоговое, поскольку только 7,5% (4000 из 55 000) административных процедур могут быть полностью завершены онлайн. Этот показатель составляет 7,8% в Министерстве экономики, торговли и промышленности, 8% в Министерстве внутренних дел и коммуникаций и только 1,3% в Министерстве сельского хозяйства, лесного хозяйства и рыболовства. [21]

12 февраля 2021 года Тетсуши Сакамото был назначен министром по вопросам одиночества для борьбы с социальной изоляцией и одиночеством среди разных возрастных групп и полов. [22]

Император Японии (天皇) является главой императорской семьи и церемониальным главой государства . Он определен Конституцией как «символ государства и единства народа». [7] Однако его роль носит исключительно церемониальный и представительский характер. Как прямо указано в статье 4 Конституции, у него нет полномочий, связанных с управлением. [23]

Статья 6 Конституции Японии делегирует Императору следующие церемониальные роли:

В то время как Кабинет является источником исполнительной власти и большая часть его полномочий осуществляется непосредственно премьер-министром , некоторые из его полномочий осуществляются через Императора. Полномочия, осуществляемые через Императора, как предусмотрено в статье 7 Конституции, следующие:

Эти полномочия осуществляются в соответствии с обязательными рекомендациями Кабинета министров.

Известно, что император обладает номинальной церемониальной властью. Например, он единственный человек, который имеет право назначать премьер-министра , хотя у парламента есть право назначать человека, подходящего для этой должности. Один из таких примеров можно наглядно увидеть в роспуске Палаты представителей в 2009 году . Ожидалось, что Палата будет распущена по совету премьер-министра, но временно не смогла сделать этого для следующих всеобщих выборов, поскольку и император, и императрица находились с визитом в Канаде . [24] [25]

Таким образом, современную роль правителя часто сравнивают с ролью периода сёгуната и большей частью истории Японии , когда император обладал большой символической властью , но имел мало политической власти ; которая часто принадлежала другим, номинально назначенным самим императором. Сегодня наследие в некоторой степени продолжилось для отставного премьер-министра, который все еще обладает значительной властью, чтобы называться Теневым сёгуном (闇将軍) . [26]

В отличие от своих европейских коллег , император не является источником суверенной власти, и правительство не действует от его имени. Вместо этого император представляет государство и назначает других высших должностных лиц от имени государства, в котором японский народ имеет суверенитет. [27] Статья 5 Конституции, в соответствии с Законом об императорском дворе , позволяет учреждать регентство от имени императора, если император не в состоянии выполнять свои обязанности. [28]

20 ноября 1989 года Верховный суд постановил, что он не имеет судебной власти над императором . [29]

Императорский дом Японии считается старейшей наследственной монархией в мире. [30] Согласно Кодзики и Нихон сёки , Япония была основана Императорским домом в 660 г. до н. э. императором Дзимму (神武天皇) . [31] Император Дзимму был первым императором Японии и предком всех последующих императоров. [32] Согласно японской мифологии , он является прямым потомком Аматэрасу (天照大御神) , богини солнца местной религии синто , через Ниниги , своего прадеда. [33] [34]

Действующий император Японии (今上天皇) — Нарухито . Он был официально возведён на престол 1 мая 2019 года после отречения своего отца. [35] [36] Он именуется Его Императорским Величеством (天皇陛下) , а его правление носит название эпохи Рэйва (令和) . Фумихито — предполагаемый наследник Хризантемового трона .

Исполнительная власть Японии возглавляется премьер-министром . Премьер-министр является главой Кабинета министров и назначается законодательным органом, Национальным парламентом . [5] Кабинет министров состоит из государственных министров и может быть назначен или уволен премьер-министром в любое время. [4] Явно определенный как источник исполнительной власти , на практике он, однако, в основном осуществляется премьер-министром. Практика его полномочий подотчетна Парламенту, и в целом, если Кабинет министров потеряет доверие и поддержку Парламента, чтобы оставаться у власти, Парламент может распустить Кабинет министров в целом с помощью вотума недоверия . [37]

Премьер -министр Японии (内閣総理大臣) назначается Национальным парламентом и служит сроком на четыре года или меньше; никаких ограничений на количество сроков, которые может занимать премьер-министр, не установлено. Премьер-министр возглавляет Кабинет министров и осуществляет «контроль и надзор» за исполнительной властью, а также является главой правительства и главнокомандующим Силами самообороны Японии . [ 38] Премьер-министр наделен полномочиями представлять законопроекты в Парламент, подписывать законы, объявлять чрезвычайное положение , а также может распускать Палату представителей Парламента по своему усмотрению. [39] Премьер-министр председательствует в Кабинете министров и назначает или увольняет других министров Кабинета министров . [4]

Обе палаты Национального парламента назначают премьер-министра голосованием по системе второго тура . Согласно Конституции, если обе палаты не придут к общему мнению относительно кандидата, то разрешается создать совместный комитет для согласования этого вопроса; в частности, в течение десяти дней, не считая периода перерыва. [40] Однако, если обе палаты все еще не пришли к согласию друг с другом, решение, принятое Палатой представителей, считается решением Национального парламента. [40] После назначения премьер-министру представляют его полномочия, а затем император официально назначает его на должность . [6]

Как кандидат, назначенный парламентом, премьер-министр обязан отчитываться перед парламентом по первому требованию. [41] Премьер-министр также должен быть как гражданским лицом , так и членом одной из палат парламента. [42]

Кабинет министров Японии (内閣) состоит из государственных министров и премьер-министра. Члены кабинета министров назначаются премьер-министром, и в соответствии с Законом о кабинете министров число назначаемых членов кабинета министров, за исключением премьер-министра, должно быть четырнадцать или меньше, но может быть увеличено до девятнадцати только в случае возникновения особой необходимости. [43] [44] Статья 68 Конституции гласит, что все члены кабинета министров должны быть гражданскими лицами , и большинство из них должны быть выбраны из числа членов любой из палат Национального парламента . [45] Точная формулировка оставляет премьер-министру возможность назначать некоторых невыборных должностных лиц парламента. [46] Кабинет министров должен уйти в отставку в полном составе , продолжая при этом выполнять свои функции до назначения нового премьер-министра, когда возникает следующая ситуация:

Концептуально получая легитимность от парламента, которому он подотчетен, Кабинет осуществляет свою власть двумя разными способами. На практике большую часть своей власти осуществляет премьер-министр, а другие номинально осуществляет император. [3]

Статья 73 Конституции Японии предполагает, что Кабинет министров будет выполнять следующие функции, помимо общего управления:

Согласно Конституции, все законы и постановления кабинета министров должны быть подписаны компетентным министром и контрассигнованы премьер-министром, прежде чем быть официально обнародованными императором . Кроме того, все члены кабинета министров не могут быть подвергнуты судебному преследованию без согласия премьер-министра; однако, без ущерба для права предпринимать судебные действия. [47]

По состоянию на 14 декабря 2023 года [update]состав Кабинета министров: [48]

Министерства Японии (中央省庁, Chuo shōcho ) состоят из одиннадцати исполнительных министерств и Кабинета министров . Каждое министерство возглавляет государственный министр , который в основном является старшим законодателем и назначается из числа членов Кабинета премьер-министром. Кабинет министров, формально возглавляемый премьер-министром, является агентством, которое занимается повседневными делами Кабинета министров. Министерства являются наиболее влиятельной частью ежедневно осуществляемой исполнительной власти, и поскольку немногие министры служат более года или около того, необходимого для того, чтобы захватить организацию, большая часть ее власти находится в руках старших бюрократов . [49]

Ниже представлен ряд связанных с министерствами правительственных агентств и бюро, ответственных за государственные процедуры и деятельность по состоянию на 23 августа 2022 года. [50]

The legislative branch organ of Japan is the National Diet (国会). It is a bicameral legislature, composing of a lower house, the House of Representatives, and an upper house, the House of Councillors. Empowered by the Constitution to be "the highest organ of State power" and the only "sole law-making organ of the State", its houses are both directly elected under a parallel voting system and is ensured by the Constitution to have no discrimination on the qualifications of each members; whether be it based on "race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property or income". The National Diet, therefore, reflects the sovereignty of the people; a principle of popular sovereignty whereby the supreme power lies within, in this case, the Japanese people.[7][51]

The Diet responsibilities includes the making of laws, the approval of the annual national budget, the approval of the conclusion of treaties and the selection of the prime minister. In addition, it has the power to initiate draft constitutional amendments, which, if approved, are to be presented to the people for ratification in a referendum before being promulgated by the Emperor, in the name of the people.[52] The Constitution also enables both houses to conduct investigations in relation to government, demand the presence and testimony of witnesses, and the production of records, as well as allowing either house of the Diet to demand the presence of the Prime Minister or the other Minister of State, in order to give answers or explanations whenever so required.[41] The Diet is also able to impeach Court judges convicted of criminal or irregular conduct. The Constitution, however, does not specify the voting methods, the number of members of each house, and all other matters pertaining to the method of election of the each members, and are thus, allowed to be determined for by law.[53]

Under the provisions of the Constitution and by law, all adults aged over 18 are eligible to vote, with a secret ballot and a universal suffrage, and those elected have certain protections from apprehension while the Diet is in session.[54] Speeches, debates, and votes cast in the Diet also enjoy parliamentary privileges. Each house is responsible for disciplining its own members, and all deliberations are public unless two-thirds or more of those members present passes a resolution agreeing it otherwise. The Diet also requires the presence of at least one-third of the membership of either house in order to constitute a quorum.[55] All decisions are decided by a majority of those present, unless otherwise stated by the Constitution, and in the case of a tie, the presiding officer has the right to decide the issue. A member cannot be expelled, however, unless a majority of two-thirds or more of those members present passes a resolution therefor.[56]

Under the Constitution, at least one session of the Diet must be convened each year. The Cabinet can also, at will, convoke extraordinary sessions of the Diet and is required to, when a quarter or more of the total members of either house demands it.[57] During an election, only the House of Representatives is dissolved. The House of Councillors is however, not dissolved but only closed, and may, in times of national emergency, be convoked for an emergency session.[58] The Emperor both convokes the Diet and dissolves the House of Representatives, but only does so on the advice of the Cabinet.

For bills to become law, they are to be first passed by both houses of the National Diet, signed by the Ministers of State, countersigned by the prime minister, and then finally promulgated by the Emperor; however, without specifically giving the Emperor the power to oppose legislation.

The House of Representatives of Japan (衆議院) is the Lower house, with the members of the house being elected once every four years, or when dissolved, for a four-year term.[59] As of November 18, 2017, it has 465 members. Of these, 176 members are elected from 11 multi-member constituencies by a party-list system of proportional representation, and 289 are elected from single-member constituencies. 233 seats are required for majority. The House of Representatives is the more powerful house out of the two, it is able to override vetoes on bills imposed by the House of Councillors with a two-thirds majority. It can, however, be dissolved by the prime minister at will.[39] Members of the house must be of Japanese nationality; those aged 18 years and older may vote, while those aged 25 years and older may run for office in the lower house.[54]

The legislative powers of the House of Representatives is considered to be more powerful than that of the House of Councillors. While the House of Councillors has the ability to veto most decisions made by the House of Representatives, some however, can only be delayed. This includes the legislation of treaties, the budget, and the selection of the prime minister. The Prime Minister, and collectively his Cabinet, can in turn, however, dissolve the House of Representatives whenever intended.[39] While the House of Representatives is considered to be officially dissolved upon the preparation of the document, the House is only formally dissolved by the dissolution ceremony.[60] The dissolution ceremony of the House is as follows:[61]

It is customary that, upon the dissolution of the House, members will shout the Three Cheers of Banzai (萬歲).[60][62]

The House of Councillors of Japan (参議院) is the Upper house, with half the members of the house being elected once every three years, for a six-year term. As of November 18, 2017, it has 242 members. Of these, 73 are elected from the 47 prefectural districts, by single non-transferable votes, and 48 are elected from a nationwide list by proportional representation with open lists. The House of Councillors cannot be dissolved by the prime minister.[58] Members of the house must be of Japanese nationality; those aged 18 years and older may vote, while those aged 30 years and older may run for office in the upper house.[54]

As the House of Councillors can veto a decision made by the House of Representatives, the House of Councillors can cause the House of Representatives to reconsider its decision. The House of Representatives however, can still insist on its decision by overriding the veto by the House of Councillors with a two-thirds majority of its members present. Each year, and when required, the National Diet is convoked at the House of Councillors, on the advice of the Cabinet, for an extra or an ordinary session, by the Emperor. A short speech is, however, usually first made by the Speaker of the House of Representatives before the Emperor proceeds to convoke the Diet with his Speech from the throne.[63]

The judicial branch of Japan consists of the Supreme Court, and four other lower courts; the High Courts, District Courts, Family Courts and Summary Courts.[64] Divided into four basic tiers, the Court's independence from the executive and legislative branches are guaranteed by the Constitution, and is stated as: "no extraordinary tribunal shall be established, nor shall any organ or agency of the Executive be given final judicial power"; a feature known as the Separation of Powers.[8] Article 76 of the Constitution states that all the Court judges are independent in the exercise of their own conscience and that they are only bounded by the Constitution and the laws.[65] Court judges are removable only by public impeachment, and can only be removed, without impeachment, when they are judicially declared mentally or physically incompetent to perform their duties.[66] The Constitution also explicitly denies any power for executive organs or agencies to administer disciplinary actions against judges.[66] However, a Supreme Court judge may be dismissed by a majority in a referendum; of which, must occur during the first general election of the National Diet's House of Representatives following the judge's appointment, and also the first general election for every ten years lapse thereafter.[67] Trials must be conducted, with judgment declared, publicly, unless the Court "unanimously determines publicity to be dangerous to public order or morals"; with the exception for trials of political offenses, offenses involving the press, and cases wherein the rights of people as guaranteed by the Constitution, which cannot be deemed and conducted privately.[68] Court judges are appointed by the Cabinet, in attestation of the Emperor, while the Chief Justice is appointed by the Emperor, after being nominated by the Cabinet; which in practice, known to be under the recommendation of the former Chief Justice.[69]

The Legal system in Japan has been historically influenced by Chinese law; developing independently during the Edo period through texts such as Kujikata Osadamegaki.[70] It has, however, changed during the Meiji Restoration, and is now largely based on the European civil law; notably, the civil code based on the German model still remains in effect.[71] A quasi-jury system has recently came into use, and the legal system also includes a bill of rights since May 3, 1947.[72] The collection of Six Codes makes up the main body of the Japanese statutory law.[71]

All Statutory Laws in Japan are required to be rubber stamped by the Emperor with the Privy Seal of Japan (天皇御璽), and no Law can take effect without the Cabinet's signature, the prime minister's countersignature and the Emperor's promulgation.[73][74][75][76][77]

The Supreme Court of Japan (最高裁判所) is the court of last resort and has the power of Judicial review; as defined by the Constitution to be "the court of last resort with power to determine the constitutionality of any law, order, regulation or official act".[78] The Supreme Court is also responsible for nominating judges to lower courts and determining judicial procedures. It also oversees the judicial system, overseeing activities of public prosecutors, and disciplining judges and other judicial personnel.[79]

The High Courts of Japan (高等裁判所) has the jurisdiction to hear appeals to judgments rendered by District Courts and Family Courts, excluding cases under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. Criminal appeals are directly handled by the High Courts, but Civil cases are first handled by District Courts. There are eight High Courts in Japan: the Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Hiroshima, Fukuoka, Sendai, Sapporo, and Takamatsu High Courts.[79]

The penal system of Japan (矯正施設) is operated by the Ministry of Justice. It is part of the criminal justice system, and is intended to resocialize, reform, and rehabilitate offenders. The ministry's Correctional Bureau administers the adult prison system, the juvenile correctional system, and three of the women's guidance homes,[80] while the Rehabilitation Bureau operates the probation and the parole systems.[81]

The Cabinet Public Affairs Office's Government Directory also listed a number of government agencies that are more independent from executive ministries.[82] The list for these types of agencies can be seen below.

According to Article 92 of the Constitution, the local governments of Japan (地方公共団体) are local public entities whose body and functions are defined by law in accordance with the principle of local autonomy.[83][84] The main law that defines them is the Local Autonomy Law.[85][86] They are given limited executive and legislative powers by the Constitution. Governors, mayors and members of assemblies are constitutionally elected by the residents.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications intervenes significantly in local government, as do other ministries. This is done chiefly financially because many local government jobs need funding initiated by national ministries. This is dubbed as the "thirty-percent autonomy".[87]

The result of this power is a high level of organizational and policy standardization among the different local jurisdictions allowing them to preserve the uniqueness of their prefecture, city, or town. Some of the more collectivist jurisdictions, such as Tokyo and Kyoto, have experimented with policies in such areas as social welfare that later were adopted by the national government.[87]

Japan is divided into forty-seven administrative divisions, the prefectures are: one metropolitan district (Tokyo), two urban prefectures (Kyoto and Osaka), forty-three rural prefectures, and one "district", Hokkaidō. Large cities are subdivided into wards, and further split into towns, or precincts, or subprefectures and counties.

Cities are self-governing units administered independently of the larger jurisdictions within which they are located. In order to attain city status, a jurisdiction must have at least 500,000 inhabitants, 60 percent of whom are engaged in urban occupations. There are self-governing towns outside the cities as well as precincts of urban wards. Like the cities, each has its own elected mayor and assembly. Villages are the smallest self-governing entities in rural areas. They often consist of a number of rural hamlets containing several thousand people connected to one another through the formally imposed framework of village administration. Villages have mayors and councils elected to four-year terms.[88][89]

Each jurisdiction has a chief executive, called a governor (知事, chiji) in prefectures and a mayor (市町村長, shichōsonchō) in municipalities. Most jurisdictions also have a unicameral assembly (議会, gikai), although towns and villages may opt for direct governance by citizens in a general assembly (総会, sōkai). Both the executive and assembly are elected by popular vote every four years.[90][91][92]

Local governments follow a modified version of the separation of powers used in the national government. An assembly may pass a vote of no confidence in the executive, in which case the executive must either dissolve the assembly within ten days or automatically lose their office. Following the next election, however, the executive remains in office unless the new assembly again passes a no confidence resolution.[85]

The primary methods of local lawmaking are local ordinance (条例, jōrei) and local regulations (規則, kisoku). Ordinances, similar to statutes in the national system, are passed by the assembly and may impose limited criminal penalties for violations (up to 2 years in prison and/or 1 million yen in fines). Regulations, similar to cabinet orders in the national system, are passed by the executive unilaterally, are superseded by any conflicting ordinances, and may only impose a fine of up to 50,000 yen.[88]

Local governments also generally have multiple committees such as school boards, public safety committees (responsible for overseeing the police), personnel committees, election committees and auditing committees.[93] These may be directly elected or chosen by the assembly, executive or both.[87]

Scholars have noted that political contestations at the local level tend not to be marked by strong party affiliation or political ideologies when compared to the national level. Moreover, in many local communities candidates from different parties tend to share similar concerns, e.g., regarding depopulation and how to attract new residents. Analyzing the political discourse among local politicians, Hijino suggests that local politics in depopulated areas is marked by two overarching ideas: "populationism" and "listenism." He writes, "“Populationism” assumes the necessity of maintaining and increasing the number of residents for the future and vitality of the municipality. “Listenism” assumes that no decision can be made unless all parties are consulted adequately, preventing majority decisions taken by elected officials over issues contested by residents. These two ideas, though not fully-fledged ideologies, are assumptions guiding the behavior of political actors in municipalities in Japan when dealing with depopulation."[94]

All prefectures are required to maintain departments of general affairs, finance, welfare, health, and labor. Departments of agriculture, fisheries, forestry, commerce, and industry are optional, depending on local needs. The Governor is responsible for all activities supported through local taxation or the national government.[87][91]