Федеральное бюро расследований ( ФБР ) — это внутренняя разведывательная и служба безопасности США и ее главное федеральное правоохранительное агентство . Агентство Министерства юстиции США , ФБР является членом разведывательного сообщества США и подчиняется как Генеральному прокурору , так и Директору национальной разведки . [3] Ведущая организация США по борьбе с терроризмом , контрразведке и уголовным расследованиям, ФБР имеет юрисдикцию в отношении нарушений более 200 категорий федеральных преступлений . [4] [5]

Хотя многие из функций ФБР уникальны, его деятельность в поддержку национальной безопасности сопоставима с деятельностью британских MI5 и NCA , новозеландского GCSB и российской ФСБ . В отличие от Центрального разведывательного управления (ЦРУ), которое не имеет правоохранительных полномочий и сосредоточено на сборе разведданных за рубежом, ФБР в первую очередь является внутренним агентством, имеющим 56 полевых отделений в крупных городах по всей территории Соединенных Штатов и более 400 постоянных агентств в небольших городах и районах по всей стране. В полевом отделении ФБР старший офицер ФБР одновременно является представителем директора национальной разведки . [6] [7]

Несмотря на свою внутреннюю направленность, ФБР также сохраняет значительное международное присутствие, управляя 60 офисами юридических атташе (LEGAT) и 15 филиалами в посольствах и консульствах США по всему миру. Эти зарубежные офисы существуют в первую очередь для координации с иностранными службами безопасности и обычно не проводят односторонних операций в принимающих странах. [8] ФБР может и иногда проводит секретную деятельность за рубежом, [9] так же, как ЦРУ имеет ограниченную внутреннюю функцию . Эта деятельность, как правило, требует координации между правительственными агентствами.

ФБР было создано в 1908 году как Бюро расследований, сокращенно BOI или BI. Его название было изменено на Федеральное бюро расследований (ФБР) в 1935 году. [10] Штаб-квартира ФБР находится в здании Дж. Эдгара Гувера в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия. У ФБР есть список 10 главных преступников .

Миссия ФБР — «защищать американский народ и соблюдать Конституцию Соединенных Штатов ». [2] [11]

В настоящее время главными приоритетами ФБР являются: [11]

В 2019 финансовом году общий бюджет Бюро составил приблизительно 9,6 млрд долларов США. [12]

В запросе на разрешение и бюджет в Конгресс на 2021 финансовый год [13] ФБР запросило $9 800 724 000. Из этих денег $9 748 829 000 будут использованы на зарплаты и расходы (S&E) и $51 895 000 на строительство. [2] Программа S&E увеличилась на $199 673 000.

В 1896 году было основано Национальное бюро по идентификации преступников , предоставлявшее агентствам по всей стране информацию для идентификации известных преступников. Убийство президента Уильяма Мак-Кинли в 1901 году создало ощущение, что Соединенным Штатам угрожают анархисты . Департаменты юстиции и труда годами вели учет анархистов, но президент Теодор Рузвельт хотел получить больше полномочий для их контроля. [14] [ нужна страница ]

Министерство юстиции было уполномочено регулировать межгосударственную торговлю с 1887 года, хотя у него не хватало персонала для этого. Оно не прилагало особых усилий для устранения нехватки персонала до скандала с мошенничеством с землей в Орегоне на рубеже 20-го века. Президент Рузвельт поручил генеральному прокурору Чарльзу Бонапарту организовать автономную следственную службу, которая будет подчиняться только генеральному прокурору . [15]

Бонапарт обратился к другим агентствам, включая Секретную службу США , за кадрами, в частности следователями. 27 мая 1908 года Конгресс запретил использование сотрудников Казначейства Министерством юстиции, сославшись на опасения, что новое агентство будет выполнять функции тайного полицейского управления. [16] Опять же по настоянию Рузвельта Бонапарт перешел к организации формального Бюро расследований , которое затем имело бы свой собственный штат специальных агентов . [14] [ нужна страница ]

Бюро расследований (BOI) было создано 26 июля 1908 года. [17] Генеральный прокурор Бонапарт, используя средства Министерства юстиции, [14] нанял тридцать четыре человека, включая некоторых ветеранов Секретной службы, [18] [19] для работы в новом следственном агентстве. Его первым «начальником» (теперь должность называется «директор») был Стэнли Финч . Бонапарт уведомил Конгресс об этих действиях в декабре 1908 года. [14]

Первой официальной задачей бюро было посещение и проведение обследований публичных домов в рамках подготовки к обеспечению соблюдения «Закона о торговле белыми рабынями» или Закона Манна , принятого 25 июня 1910 года. В 1932 году бюро было переименовано в Бюро расследований США.

В следующем, 1933 году, BOI был связан с Бюро по запрету и переименован в Отдел расследований (DOI); в 1935 году он стал независимой службой в составе Министерства юстиции. [18] В том же году его название было официально изменено с Отдела расследований на Федеральное бюро расследований (ФБР).

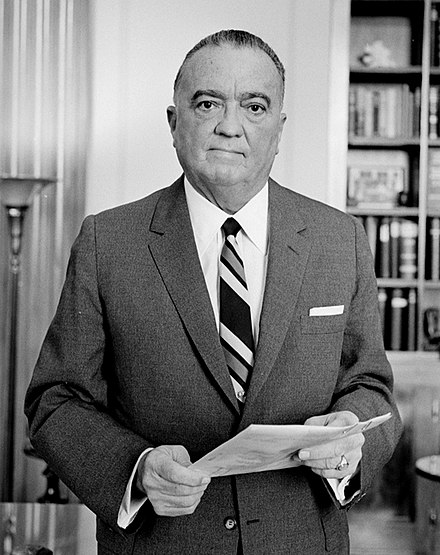

Дж. Эдгар Гувер занимал пост директора ФБР с 1924 по 1972 год, в общей сложности 48 лет в BOI, DOI и ФБР. Он был главным ответственным за создание Научной лаборатории по раскрытию преступлений или Лаборатории ФБР , которая официально открылась в 1932 году в рамках его работы по профессионализации расследований правительством. Гувер принимал существенное участие в большинстве крупных дел и проектов, которыми занималось ФБР во время его пребывания в должности. Но, как подробно описано ниже, его пребывание в должности директора Бюро оказалось весьма спорным, особенно в последние годы. После смерти Гувера Конгресс принял закон, ограничивающий срок полномочий будущих директоров ФБР десятью годами.

Ранние расследования убийств нового агентства включали убийства индейцев племени Осейдж . Во время «войны с преступностью» 1930-х годов агенты ФБР задержали или убили ряд известных преступников, которые совершали похищения, ограбления банков и убийства по всей стране, включая Джона Диллинджера , «Малыша» Нельсона , Кейт «Ма» Баркер , Элвина «Жуткого» Карписа и Джорджа «Пулемета» Келли .

Другие виды деятельности в первые десятилетия были сосредоточены на масштабах и влиянии белой супремасистской группировки Ку-клукс-клан , с которой, как было доказано, ФБР работало в деле о линчевании Виолы Лиуццо . Ранее, благодаря работе Эдвина Атертона , BOI утверждал, что успешно задержал целую армию мексиканских нео-революционеров под руководством генерала Энрике Эстрады в середине 1920-х годов к востоку от Сан-Диего, Калифорния.

Гувер начал использовать прослушивание телефонных разговоров в 1920-х годах во время сухого закона для ареста бутлегеров. [20] В деле 1927 года Олмстед против Соединенных Штатов , в котором бутлегер был пойман с помощью прослушивания телефона, Верховный суд Соединенных Штатов постановил, что прослушивание телефонных разговоров ФБР не нарушает Четвертую поправку как незаконный обыск и изъятие, при условии, что ФБР не врывается в дом человека, чтобы завершить прослушивание. [20] После отмены сухого закона Конгресс принял Закон о коммуникациях 1934 года , который запретил несогласованное прослушивание телефонных разговоров, но разрешил установку подслушивающих устройств. [20] В деле 1939 года Нардоне против Соединенных Штатов суд постановил, что в соответствии с законом 1934 года доказательства, полученные ФБР с помощью прослушивания телефонных разговоров, недопустимы в суде. [20] После того, как решение по делу Кац против Соединенных Штатов (1967) было отменено , Конгресс принял Закон о борьбе с преступностью , позволяющий государственным органам прослушивать телефоны во время расследований, при условии предварительного получения ордера. [20]

Начиная с 1940-х и продолжая 1970-е годы, бюро расследовало случаи шпионажа против Соединенных Штатов и их союзников. Восемь нацистских агентов, которые планировали диверсионные операции против американских целей, были арестованы, и шесть были казнены ( Ex parte Quirin ) по их приговорам. Также в это время совместная работа США и Великобритании по взлому кодов под названием « Проект Венона », в которой ФБР принимало активное участие, взломала советские дипломатические и разведывательные коды связи, что позволило правительствам США и Великобритании читать советские сообщения. Эта работа подтвердила существование американцев, работающих в Соединенных Штатах на советскую разведку. [21] Гувер руководил этим проектом, но он не уведомил Центральное разведывательное управление (ЦРУ) о нем до 1952 года. Другим примечательным случаем стал арест советского шпиона Рудольфа Абеля в 1957 году. [22] Обнаружение советских шпионов, работающих в США, побудило Гувера заняться своей давней проблемой угрозы, которую он ощущал со стороны американских левых .

В 1939 году Бюро начало составлять список лиц, подлежащих задержанию , с именами тех, кто будет взят под стражу в случае войны со странами Оси. Большинство имен в списке принадлежали лидерам общины Иссей , поскольку расследование ФБР основывалось на существующем индексе военно-морской разведки , который был сосредоточен на японоамериканцах на Гавайях и Западном побережье, но многие граждане Германии и Италии также попали в список индекса ФБР . [23] Роберт Шиверс, глава офиса в Гонолулу, получил разрешение от Гувера начать задержание тех, кто был в списке, 7 декабря 1941 года, когда бомбы все еще падали на Перл-Харбор . [24] [ нужен лучший источник ] Массовые аресты и обыски домов, в большинстве случаев проводимые без ордеров, начались через несколько часов после атаки, и в течение следующих нескольких недель более 5500 мужчин Иссей были взяты под стражу ФБР. [25]

19 февраля 1942 года президент Франклин Рузвельт издал Указ 9066 , разрешающий высылку японоамериканцев с Западного побережья. Директор ФБР Гувер выступил против последующего массового выселения и заключения японоамериканцев, разрешенного Указом 9066, но Рузвельт одержал победу. [26] Подавляющее большинство согласилось с последующими приказами об исключении, но в нескольких случаях, когда японоамериканцы отказывались подчиняться новым военным правилам, агенты ФБР занимались их арестами. [24] Бюро продолжало наблюдение за японоамериканцами на протяжении всей войны, проводя проверки биографических данных претендентов на переселение за пределы лагеря и въезда в лагеря, как правило, без разрешения должностных лиц Управления по перемещению военных , и готовя информаторов для слежки за диссидентами и «нарушителями спокойствия». После войны ФБР было поручено защищать возвращающихся японоамериканцев от нападений со стороны враждебных белых общин. [24]

По словам Дугласа М. Чарльза, программа ФБР по «сексуальным извращенцам» началась 10 апреля 1950 года, когда Дж. Эдгар Гувер направил в Белый дом, Комиссию по гражданской службе США и подразделения вооруженных сил список из 393 предполагаемых федеральных служащих, которые предположительно были арестованы в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, с 1947 года по обвинению в «сексуальных нарушениях». 20 июня 1951 года Гувер расширил программу, выпустив меморандум, устанавливающий «единую политику обработки растущего числа сообщений и заявлений, касающихся нынешних и бывших служащих правительства Соединенных Штатов, которые предположительно [sic] являются сексуальными извращенцами». Программа была расширена и теперь включает в себя негосударственные должности. По словам Атана Теохариса , «в 1951 году он [Гувер] в одностороннем порядке учредил программу по борьбе с сексуальными отклонениями, чтобы очистить предполагаемых гомосексуалистов от любой должности в федеральном правительстве, от самого низшего клерка до более влиятельной должности помощника Белого дома». 27 мая 1953 года вступил в силу Указ президента 10450. Программа была расширена этим указом еще больше, сделав незаконным все федеральное трудоустройство гомосексуалистов. 8 июля 1953 года ФБР направило в Комиссию по гражданской службе США информацию из программы по борьбе с сексуальными отклонениями. В период с 1977 по 1978 год 300 000 страниц программы по борьбе с сексуальными отклонениями, собранные между 1930 и серединой 1970-х годов, были уничтожены сотрудниками ФБР. [27] [28] [29]

В 1950-х и 1960-х годах сотрудники ФБР все больше беспокоились о влиянии лидеров движения за гражданские права, которые, по их мнению, либо имели связи с коммунистами, либо находились под неправомерным влиянием коммунистов или « попутчиков ». Например, в 1956 году Гувер направил открытое письмо, осуждающее доктора Т. Р. М. Говарда , лидера движения за гражданские права, хирурга и богатого предпринимателя из Миссисипи, который критиковал бездействие ФБР в раскрытии недавних убийств Джорджа У. Ли , Эммета Тилла и других чернокожих на Юге. [30] ФБР проводило противоречивую внутреннюю слежку в ходе операции, которую оно назвало COINTELPRO , от «COunter-INTELligence PROgram». [31] Она заключалась в расследовании и пресечении деятельности диссидентских политических организаций в Соединенных Штатах, включая как воинствующие, так и ненасильственные организации. Среди ее целей была Конференция южного христианского лидерства , ведущая организация по гражданским правам, духовным руководством которой был преподобный доктор Мартин Лютер Кинг-младший . [32]

ФБР часто расследовало деятельность Кинга. В середине 1960-х годов Кинг начал критиковать Бюро за то, что оно уделяло недостаточно внимания использованию терроризма сторонниками превосходства белой расы. Гувер ответил, публично назвав Кинга самым «отъявленным лжецом» в Соединенных Штатах. [34] В своих мемуарах 1991 года журналист Washington Post Карл Роуэн утверждал, что ФБР отправило Кингу по крайней мере одно анонимное письмо, призывающее его совершить самоубийство. [35] Историк Тейлор Бранч документирует анонимную «посылку о самоубийстве», отправленную Бюро в ноябре 1964 года, которая объединяла письмо лидеру движения за гражданские права, в котором говорилось: «С тобой покончено. Для тебя есть только один выход», с аудиозаписями сексуальных проступков Кинга. [36]

В марте 1971 года жилой офис агента ФБР в Медиа, штат Пенсильвания, был ограблен группой, называющей себя Гражданской комиссией по расследованию деятельности ФБР . Многочисленные файлы были изъяты и распространены среди ряда газет, включая The Harvard Crimson . [37] В файлах подробно описывалась обширная программа ФБР COINTELPRO , которая включала расследования жизни простых граждан, включая группу чернокожих студентов в военном колледже Пенсильвании и дочь конгрессмена Генри С. Ройсса из Висконсина . [37] Страна была «встряхнута» разоблачениями, которые включали убийства политических активистов, и эти действия были осуждены членами Конгресса, включая лидера большинства в Палате представителей Хейла Боггса . [37] Телефоны некоторых членов Конгресса, включая Боггса, предположительно прослушивались. [37]

Когда был застрелен президент Джон Ф. Кеннеди , юрисдикция перешла к местным полицейским управлениям, пока президент Линдон Б. Джонсон не поручил ФБР взять расследование под свой контроль. [38] Чтобы обеспечить ясность в отношении ответственности за расследование убийств федеральных чиновников, Конгресс принял в 1965 году закон, который включал расследования таких смертей федеральных чиновников, особенно в результате убийств, в юрисдикцию ФБР. [39] [40] [41]

В ответ на организованную преступность 25 августа 1953 года ФБР создало программу Top Hoodlum Program. Национальное управление поручило полевым отделениям собирать информацию о гангстерах на своих территориях и регулярно сообщать ее в Вашингтон для централизованного сбора разведданных о рэкетирах . [42] После того, как Закон о коррумпированных и находящихся под влиянием рэкетиров организациях (Закон RICO) вступил в силу, ФБР начало расследование бывших организованных по сухому закону групп, которые стали прикрытием для преступности в крупных городах и небольших городках. Вся работа ФБР проводилась под прикрытием и изнутри этих организаций с использованием положений, предусмотренных в Законе RICO. Постепенно агентство расформировало многие из групп. Хотя Гувер изначально отрицал существование Национального преступного синдиката в Соединенных Штатах, Бюро позже проводило операции против известных организованных преступных синдикатов и семей, включая те, которые возглавляли Сэм Джанкана и Джон Готти . Закон RICO по сей день применяется в отношении всех видов организованной преступности и любых лиц, которые могут подпадать под положения этого закона.

В 2003 году комитет Конгресса назвал программу ФБР по информаторам об организованной преступности «одним из величайших провалов в истории федеральных правоохранительных органов». [43] ФБР позволило осудить четырех невиновных мужчин за убийство Эдварда «Тедди» Дигана, совершенное бандитами в марте 1965 года , чтобы защитить Винсента Флемми , информатора ФБР. Трое из мужчин были приговорены к смертной казни (которая позже была заменена пожизненным заключением), а четвертый обвиняемый был приговорен к пожизненному заключению. [43] Двое из четырех мужчин умерли в тюрьме, отсидев почти 30 лет, а двое других были освобождены, отсидев 32 и 36 лет. В июле 2007 года окружной судья США Нэнси Гертнер в Бостоне обнаружила, что Бюро помогло осудить четырех мужчин, используя ложные свидетельские показания, данные гангстером Джозефом Барбозой . Правительству США было предписано выплатить 100 миллионов долларов в качестве компенсации ущерба четырем обвиняемым. [44]

В 1982 году ФБР сформировало элитное подразделение [45] для помощи в решении проблем, которые могли возникнуть на летних Олимпийских играх 1984 года , которые должны были состояться в Лос-Анджелесе, в частности, терроризма и крупных преступлений. Это стало результатом летних Олимпийских игр 1972 года в Мюнхене, Германия , когда террористы убили израильских спортсменов . Названная Hostage Rescue Team , или HRT, она действует как специализированная группа спецназа ФБР , занимающаяся в основном контртеррористическими сценариями. В отличие от специальных агентов, работающих в местных группах спецназа ФБР , HRT не проводит расследований. Вместо этого HRT фокусируется исключительно на дополнительных тактических навыках и возможностях. Также в 1984 году была сформирована Computer Analysis and Response Team , или CART. [46]

С конца 1980-х до начала 1990-х годов ФБР перенаправило более 300 агентов из иностранных контрразведывательных служб в отделы по борьбе с насильственными преступлениями и сделало борьбу с насильственными преступлениями шестым национальным приоритетом. С сокращениями в других хорошо зарекомендовавших себя департаментах и потому, что терроризм больше не считался угрозой после окончания Холодной войны , [46] ФБР помогало местным и государственным полицейским силам в отслеживании беглецов, которые пересекли границы штатов, что является федеральным преступлением. Лаборатория ФБР помогла разработать ДНК- тестирование, продолжив свою новаторскую роль в идентификации, которая началась с ее системы дактилоскопии в 1924 году.

1 мая 1992 года сотрудники SWAT ФБР и HRT в округе Лос-Анджелес, штат Калифорния, помогали местным властям обеспечивать мир в этом районе во время беспорядков в Лос-Анджелесе в 1992 году . Например, операторы HRT в течение 10 дней проводили патрулирование на транспортных средствах по всему Лос-Анджелесу , прежде чем вернуться в Вирджинию. [47]

В период с 1993 по 1996 год ФБР усилило свою контртеррористическую роль после первого взрыва Всемирного торгового центра в Нью-Йорке в 1993 году , взрыва в Оклахома-Сити в 1995 году и ареста Унабомбера в 1996 году. Технологические инновации и навыки аналитиков лаборатории ФБР помогли обеспечить успешное судебное преследование по всем трем делам. [48] Однако было обнаружено, что расследования Министерства юстиции относительно роли ФБР в инцидентах в Руби-Ридж и Уэйко были затруднены агентами внутри Бюро. Во время летних Олимпийских игр 1996 года в Атланте, штат Джорджия , ФБР подверглось критике за расследование взрыва в Олимпийском парке Сентенниал . Оно урегулировало спор с Ричардом Джуэллом , который был частным охранником на месте проведения, а также с некоторыми медиа-организациями [49] в отношении утечки его имени во время расследования; это на короткое время привело к тому, что его ошибочно подозревали в организации взрыва.

После того, как Конгресс принял Закон о коммуникационной помощи правоохранительным органам (CALEA, 1994), Закон о переносимости и подотчетности медицинского страхования (HIPAA, 1996) и Закон об экономическом шпионаже (EEA, 1996), ФБР последовало их примеру и в 1998 году провело технологическую модернизацию, как и в случае с командой CART в 1991 году. Были созданы Центр компьютерных расследований и оценки угроз инфраструктуре (CITAC) и Национальный центр защиты инфраструктуры (NIPC) для борьбы с ростом числа проблем, связанных с Интернетом , таких как компьютерные вирусы, черви и другие вредоносные программы, которые угрожали операциям США. Благодаря этим разработкам ФБР усилило свое электронное наблюдение в расследованиях в сфере общественной и национальной безопасности, адаптируясь к достижениям в области телекоммуникаций, которые изменили характер таких проблем.

Во время атак на Всемирный торговый центр 11 сентября 2001 года агент ФБР Леонард В. Хэттон-младший был убит во время спасательной операции, помогая спасателям эвакуировать людей из Южной башни, и он остался, когда она рухнула. Через несколько месяцев после атак директор ФБР Роберт Мюллер , который был приведен к присяге за неделю до атак, призвал к реорганизации структуры и операций ФБР. Он сделал противодействие каждому федеральному преступлению главным приоритетом, включая предотвращение терроризма, противодействие операциям иностранной разведки, устранение угроз кибербезопасности, других преступлений в сфере высоких технологий, защиту гражданских прав, борьбу с государственной коррупцией, организованной преступностью, преступлениями «белых воротничков» и тяжкими насильственными преступлениями. [50]

В феврале 2001 года Роберт Ханссен был пойман на продаже информации российскому правительству. Позже стало известно, что Ханссен, достигший высокого положения в ФБР, продавал разведданные еще с 1979 года. Он признал себя виновным в шпионаже и получил пожизненное заключение в 2002 году, но инцидент заставил многих усомниться в методах обеспечения безопасности, используемых ФБР. Также было высказано утверждение, что Ханссен мог предоставить информацию, которая привела к атакам 11 сентября 2001 года. [51]

В заключительном отчете Комиссии по 11 сентября от 22 июля 2004 года говорилось, что ФБР и Центральное разведывательное управление (ЦРУ) частично виноваты в том, что не расследовали отчеты разведки, которые могли бы предотвратить атаки 11 сентября. В своей самой осуждающей оценке отчет пришел к выводу, что страна «не получила должного обслуживания» от обоих агентств, и перечислил многочисленные рекомендации по изменениям в ФБР. [52] Хотя ФБР согласилось с большинством рекомендаций, включая надзор со стороны нового директора Национальной разведки , некоторые бывшие члены Комиссии по 11 сентября публично раскритиковали ФБР в октябре 2005 года, заявив, что оно сопротивляется любым значимым изменениям. [53]

8 июля 2007 года The Washington Post опубликовала отрывки из книги профессора Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе Эми Зегарт «Шпионаж вслепую: ЦРУ, ФБР и истоки 11 сентября» . [54] The Post сообщила, основываясь на книге Зегарт, что правительственные документы показали, что и ЦРУ, и ФБР упустили 23 потенциальных шанса предотвратить террористические атаки 11 сентября 2001 года. Основными причинами неудач были: корпоративная культура, устойчивая к изменениям и новым идеям; ненадлежащие стимулы для продвижения по службе; и отсутствие сотрудничества между ФБР, ЦРУ и остальной частью разведывательного сообщества США . В книге обвинялась децентрализованная структура ФБР, которая препятствовала эффективной коммуникации и сотрудничеству между различными офисами ФБР. В книге предполагалось, что ФБР не превратилось в эффективное контртеррористическое или контрразведывательное агентство, во многом из-за глубоко укоренившегося культурного сопротивления агентств изменениям. Например, кадровая практика ФБР продолжала относиться ко всем сотрудникам, кроме специальных агентов, как к вспомогательному персоналу, классифицируя аналитиков разведки наравне с автомеханиками и уборщиками ФБР. [55]

На протяжении более 40 лет криминалистическая лаборатория ФБР в Квантико считала, что свинцовые сплавы, используемые в пулях, имеют уникальные химические сигнатуры. Она анализировала пули с целью их химического сопоставления не только с одной партией боеприпасов, поступающих с завода, но и с одной коробкой пуль. Национальная академия наук провела 18-месячный независимый обзор сравнительного анализа свинца пуль . В 2003 году ее Национальный исследовательский совет опубликовал отчет, выводы которого поставили под сомнение 30 лет показаний ФБР. Он обнаружил, что аналитическая модель, используемая ФБР для интерпретации результатов, была глубоко ошибочной, а вывод о том, что фрагменты пуль можно сопоставить с коробкой боеприпасов, был настолько преувеличен, что вводил в заблуждение в соответствии с правилами доказывания. Год спустя ФБР решило прекратить проводить анализы свинца пуль. [56]

После расследования 60 Minutes / The Washington Post в ноябре 2007 года, два года спустя, Бюро согласилось выявить, рассмотреть и опубликовать все соответствующие дела, а также уведомить прокуроров о делах, в которых были даны ложные показания. [57]

В 2012 году ФБР сформировало Национальный центр содействия внутренним коммуникациям для разработки технологий оказания помощи правоохранительным органам в предоставлении технических знаний в области коммуникационных услуг, технологий и электронного наблюдения. [58]

Информатор ФБР, участвовавший в нападении на демократические институты в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, 6 января 2021 года , позже дал показания в поддержку Proud boys , которые были частью заговора. Разоблачения об информаторе подняли новые вопросы о провалах разведки ФБР до беспорядков. По данным Центра Бреннана и комитетов Сената , реакция ФБР на насилие со стороны сторонников превосходства белой расы была «ужасно неадекватной». ФБР давно подозревается в том, что закрывало глаза на правых экстремистов, распространяя «теории заговора» о происхождении COVID-19 . [59] [60] [61]

.pdf/page1-440px-Counterterrorism_Policy_Directive_and_Policy_Guide_(redacted).pdf.jpg)

ФБР состоит из функциональных отделений и Управления директора, в котором находится большинство административных офисов. Каждым отделением управляет помощник исполнительного директора. Каждое отделение затем делится на офисы и отделы, каждый из которых возглавляется помощником директора. Различные отделы далее делятся на подотделения, возглавляемые заместителями помощников директора. Внутри этих подотделений существуют различные отделы, возглавляемые начальниками отделов. Начальники отделов ранжируются аналогично ответственным специальным агентам. Четыре отделения подчиняются заместителю директора, а два — заместителю директора.

Основными подразделениями ФБР являются: [62]

Каждая ветвь фокусируется на разных задачах, а некоторые фокусируются на более чем одной. Вот некоторые из задач, за которые отвечают разные ветви:

Отделение национальной безопасности (NSB) [2] [63]

Разведывательное отделение (IB) [2]

Отделение ФБР по расследованию преступлений, киберпреступлений и предоставлению услуг (CCRSB) [2] [64]

Отделение науки и технологий (STB) [2] [64] [66]

Отделение информации и технологий (ITB) [2] [67] [64]

Отдел кадров (HRB) [2] [64]

Административная и финансовая поддержка управления [2]

Офис директора является центральным административным органом ФБР. Офис предоставляет функции поддержки персонала (такие как управление финансами и объектами) пяти функциональным отделениям и различным полевым подразделениям. Офисом руководит заместитель директора ФБР, который также курирует деятельность как информационно-технологического, так и кадрового отделений.

Старший персонал [62]

Кабинет директора [62]

Ниже приведен список ранговой структуры ФБР (в порядке возрастания): [68] [ проверка не удалась ]

The FBI's mandate is established in Title 28 of the United States Code (U.S. Code), Section 533, which authorizes the Attorney General to "appoint officials to detect and prosecute crimes against the United States."[69] Other federal statutes give the FBI the authority and responsibility to investigate specific crimes.

The FBI's chief tool against organized crime is the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. The FBI is also charged with the responsibility of enforcing compliance of the United States Civil Rights Act of 1964 and investigating violations of the act in addition to prosecuting such violations with the United States Department of Justice (DOJ). The FBI also shares concurrent jurisdiction with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in the enforcement of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.

The USA PATRIOT Act increased the powers allotted to the FBI, especially in wiretapping and monitoring of Internet activity. One of the most controversial provisions of the act is the so-called sneak and peek provision, granting the FBI powers to search a house while the residents are away, and not requiring them to notify the residents for several weeks afterward. Under the PATRIOT Act's provisions, the FBI also resumed inquiring into the library records[70] of those who are suspected of terrorism (something it had supposedly not done since the 1970s).

In the early 1980s, Senate hearings were held to examine FBI undercover operations in the wake of the Abscam controversy, which had allegations of entrapment of elected officials. As a result, in the following years a number of guidelines were issued to constrain FBI activities.

Information obtained through an FBI investigation is presented to the appropriate U.S. Attorney or Department of Justice official, who decides if prosecution or other action is warranted.

The FBI often works in conjunction with other federal agencies, including the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) in seaport and airport security,[71] and the National Transportation Safety Board in investigating airplane crashes and other critical incidents. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) has nearly the same amount of investigative manpower as the FBI and investigates the largest range of crimes. In the wake of the September 11 attacks, then–Attorney General Ashcroft assigned the FBI as the designated lead organization in terrorism investigations after the creation of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. HSI and the FBI are both integral members of the Joint Terrorism Task Force.

.jpg/440px-FBI_Director_Visits_North_Dakota_Indian_Reservation_(27474029651).jpg)

The federal government has the primary responsibility for investigating[72] and prosecuting serious crime on Indian reservations.[73]

There are 565 federally recognized American Indian Tribes in the United States, and the FBI has federal law enforcement responsibility on nearly 200 Indian reservations. This federal jurisdiction is shared concurrently with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Justice Services (BIA-OJS).

Located within the FBI's Criminal Investigative Division, the Indian Country Crimes Unit (ICCU) is responsible for developing and implementing strategies, programs, and policies to address identified crime problems in Indian Country (IC) for which the FBI has responsibility.— Overview, Indian Country Crime[74]

The FBI does not specifically list crimes in Native American land as one of its priorities.[75] Often serious crimes have been either poorly investigated or prosecution has been declined. Tribal courts can impose sentences of up to three years, under certain restrictions.[76][77]

.jpg/440px-FBI_Headquarters_-_J._Edgar_Hoover_Building_(53840035941).jpg)

The FBI is headquartered at the J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington, D.C., with 56 field offices[78] in major cities across the United States. The FBI also maintains over 400 resident agencies across the United States, as well as over 50 legal attachés at United States embassies and consulates. Many specialized FBI functions are located at facilities in Quantico, Virginia, as well as a "data campus" in Clarksburg, West Virginia, where 96 million sets of fingerprints "from across the United States are stored, along with others collected by American authorities from prisoners in Saudi Arabia and Yemen, Iraq and Afghanistan."[79] The FBI is in process of moving its Records Management Division, which processes Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, to Winchester, Virginia.[80]

According to The Washington Post, the FBI "is building a vast repository controlled by people who work in a top-secret vault on the fourth floor of the J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington. This one stores the profiles of tens of thousands of Americans and legal residents who are not accused of any crime. What they have done is appear to be acting suspiciously to a town sheriff, a traffic cop or even a neighbor."[79]

The FBI Laboratory, established with the formation of the BOI,[81] did not appear in the J. Edgar Hoover Building until its completion in 1974. The lab serves as the primary lab for most DNA, biological, and physical work. Public tours of FBI headquarters ran through the FBI laboratory workspace before the move to the J. Edgar Hoover Building. The services the lab conducts include Chemistry, Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), Computer Analysis and Response, DNA Analysis, Evidence Response, Explosives, Firearms and Tool marks, Forensic Audio, Forensic Video, Image Analysis, Forensic Science Research, Forensic Science Training, Hazardous Materials Response, Investigative and Prospective Graphics, Latent Prints, Materials Analysis, Questioned Documents, Racketeering Records, Special Photographic Analysis, Structural Design, and Trace Evidence.[82] The services of the FBI Laboratory are used by many state, local, and international agencies free of charge. The lab also maintains a second lab at the FBI Academy.

The FBI Academy, located in Quantico, Virginia, is home to the communications and computer laboratory the FBI utilizes. It is also where new agents are sent for training to become FBI special agents. Going through the 21-week course is required for every special agent.[83] First opened for use in 1972, the facility is located on 385 acres (156 hectares) of woodland. The Academy trains state and local law enforcement agencies, which are invited to the law enforcement training center. The FBI units that reside at Quantico are the Field and Police Training Unit, Firearms Training Unit, Forensic Science Research and Training Center, Technology Services Unit (TSU), Investigative Training Unit, Law Enforcement Communication Unit, Leadership and Management Science Units (LSMU), Physical Training Unit, New Agents' Training Unit (NATU), Practical Applications Unit (PAU), the Investigative Computer Training Unit and the "College of Analytical Studies".

In 2000, the FBI began the Trilogy project to upgrade its outdated information technology (IT) infrastructure. This project, originally scheduled to take three years and cost around $380 million, ended up over budget and behind schedule.[84] Efforts to deploy modern computers and networking equipment were generally successful, but attempts to develop new investigation software, outsourced to Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), were not. Virtual Case File, or VCF, as the software was known, was plagued by poorly defined goals, and repeated changes in management.[85]

In January 2005, more than two years after the software was originally planned for completion, the FBI abandoned the project. At least $100 million, and much more by some estimates, was spent on the project, which never became operational. The FBI has been forced to continue using its decade-old Automated Case Support system, which IT experts consider woefully inadequate. In March 2005, the FBI announced it was beginning a new, more ambitious software project, code-named Sentinel, which they expected to complete by 2009.[86]

Carnivore was an electronic eavesdropping software system implemented by the FBI during the Clinton administration; it was designed to monitor email and electronic communications. After prolonged negative coverage in the press, the FBI changed the name of its system from "Carnivore" to "DCS1000". DCS is reported to stand for "Digital Collection System"; the system has the same functions as before. The Associated Press reported in mid-January 2005 that the FBI essentially abandoned the use of Carnivore in 2001, in favor of commercially available software, such as NarusInsight.

The Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division[87] is located in Clarksburg, West Virginia. Organized beginning in 1991, the office opened in 1995 as the youngest agency division. The complex is the length of three football fields. It provides a main repository for information in various data systems. Under the roof of the CJIS are the programs for the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR), Fingerprint Identification, Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS), NCIC 2000, and the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). Many state and local agencies use these data systems as a source for their own investigations and contribute to the database using secure communications. FBI provides these tools of sophisticated identification and information services to local, state, federal, and international law enforcement agencies.

The FBI heads the National Virtual Translation Center, which provides "timely and accurate translations of foreign intelligence for all elements of the Intelligence Community."[88]

In June 2021, the FBI held a groundbreaking for its planned FBI Innovation Center, set to be built in Huntsville, Alabama. The Innovation Center is to be part of a large, college-like campus costing a total of $1.3 billion in Redstone Arsenal and will act as a center for cyber threat intelligence, data analytics, and emerging threat training.[89]

As of December 31, 2009[update], the FBI had a total of 33,852 employees. That includes 13,412 special agents and 20,420 support professionals, such as intelligence analysts, language specialists, scientists, information technology specialists, and other professionals.[90]

The Officer Down Memorial Page provides the biographies of 86 FBI agents who have died in the line of duty from 1925 to February 2021.[91]

To apply to become an FBI agent, one must be between the ages of 23 and 37, unless one is a preference-eligible veteran, in which case one may apply after age 37.[92] The applicant must also hold U.S. citizenship, be of high moral character, have a clean record, and hold at least a four-year bachelor's degree. At least three years of professional work experience prior to application is also required. All FBI employees require a Top Secret (TS) security clearance, and in many instances, employees need a TS/SCI (Top Secret/Sensitive Compartmented Information) clearance.[93]

To obtain a security clearance, all potential FBI personnel must pass a series of Single Scope Background Investigations (SSBI), which are conducted by the Office of Personnel Management.[94] Special agent candidates also have to pass a Physical Fitness Test (PFT), which includes a 300-meter run, one-minute sit-ups, maximum push-ups, and a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) run. Personnel must pass a polygraph test with questions including possible drug use.[95] Applicants who fail polygraphs may not gain employment with the FBI.[96] Up until 1975, the FBI had a minimum height requirement of 5 feet 7 inches (170 cm).[97]

FBI directors are appointed (nominated) by the President of the United States and must be confirmed by the United States Senate to serve a term of office of ten years, subject to resignation or removal by the President at his/her discretion before their term ends. Additional terms are allowed following the same procedure.

J. Edgar Hoover, appointed by President Calvin Coolidge in 1924, was by far the longest-serving director, serving until his death in 1972. In 1968, Congress passed legislation, as part of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, requiring Senate confirmation of appointments of future directors.[98] As the incumbent, this legislation did not apply to Hoover. The last FBI director was Andrew McCabe. The current FBI director is Christopher A. Wray, appointed by President Donald Trump.

The FBI director is responsible for the day-to-day operations at the FBI. Along with the deputy director, the director makes sure cases and operations are handled correctly. The director also is in charge of making sure the leadership in the FBI field offices is staffed with qualified agents. Before the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act was passed in the wake of the September 11 attacks, the FBI director would directly brief the President of the United States on any issues that arise from within the FBI. Since then, the director now reports to the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), who in turn reports to the President.

Upon qualification, an FBI special agent is issued a full-size Glock 22 or compact Glock 23 semi-automatic pistol, both of which are chambered in the .40 S&W cartridge. In May 1997, the FBI officially adopted the Glock, in .40 S&W, for general agent use, and first issued it to New Agent Class 98-1 in October 1997. At present, the Glock 23 "FG&R" (finger groove and rail; either 3rd generation or "Gen4") is the issue sidearm.[99]

New agents are issued firearms, on which they must qualify, on successful completion of their training at the FBI Academy. The Glock 26 (subcompact 9 mm Parabellum), Glock 23 and Glock 27 (.40 S&W compact and subcompact, respectively) are authorized as secondary weapons. Special agents are also authorized to purchase and qualify with the Glock 21 in .45 ACP.[100]

Special agents of the FBI Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) and regional SWAT teams are issued the Springfield Armory Professional Model 1911 pistol in .45 ACP.[101][102][103]

In June 2016, the FBI awarded Glock a contract for new handguns. Unlike the currently issued .40 S&W chambered Glock pistols, the new Glocks will be chambered for 9 mm Parabellum. The contract is for the full-size Glock 17M and the compact Glock 19M. The "M" means the Glocks have been modified to meet government standards specified by a 2015 government request for proposal.[104][105][106][107][108]

The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin is published monthly by the FBI Law Enforcement Communication Unit,[109] with articles of interest to state and local law enforcement personnel. First published in 1932 as Fugitives Wanted by Police,[110] the FBI Law Bulletin covers topics including law enforcement technology and issues, such as crime mapping and use of force, as well as recent criminal justice research, and ViCAP alerts, on wanted suspects and key cases.

The FBI also publishes some reports for both law enforcement personnel as well as regular citizens covering topics including law enforcement, terrorism, cybercrime, white-collar crime, violent crime, and statistics.[111] The vast majority of federal government publications covering these topics are published by the Office of Justice Programs agencies of the United States Department of Justice, and disseminated through the National Criminal Justice Reference Service.

During the 1920s the FBI began issuing crime reports by gathering numbers from local police departments.[112] Due to limitations of this system that were discovered during the 1960s and 1970s—victims often simply did not report crimes to the police in the first place—the Department of Justice developed an alternative method of tallying crime, the victimization survey.[112]

The Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) compile data from over 17,000 law enforcement agencies across the country. They provide detailed data regarding the volume of crimes to include arrest, clearance (or closing a case), and law enforcement officer information. The UCR focuses its data collection on violent crimes, hate crimes, and property crimes.[111] Created in the 1920s, the UCR system has not proven to be as uniform as its name implies. The UCR data only reflect the most serious offense in the case of connected crimes and has a very restrictive definition of rape. Since about 93% of the data submitted to the FBI is in this format, the UCR stands out as the publication of choice as most states require law enforcement agencies to submit this data.

Preliminary Annual Uniform Crime Report for 2006 was released on June 4, 2006. The report shows violent crime offenses rose 1.3%, but the number of property crime offenses decreased 2.9% compared to 2005.[113]

The National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) crime statistics system aims to address limitations inherent in UCR data. The system is used by law enforcement agencies in the United States for collecting and reporting data on crimes. Local, state, and federal agencies generate NIBRS data from their records management systems. Data is collected on every incident and arrest in the Group A offense category. The Group A offenses are 46 specific crimes grouped in 22 offense categories. Specific facts about these offenses are gathered and reported in the NIBRS system. In addition to the Group A offenses, eleven Group B offenses are reported with only the arrest information. The NIBRS system is in greater detail than the summary-based UCR system. As of 2004[update], 5,271 law enforcement agencies submitted NIBRS data. That amount represents 20% of the United States population and 16% of the crime statistics data collected by the FBI.

eGuardian is the name of an FBI system, launched in January 2009, to share tips about possible terror threats with local police agencies. The program aims to get law enforcement at all levels sharing data quickly about suspicious activity and people.[114]

eGuardian enables near real-time sharing and tracking of terror information and suspicious activities with local, state, tribal, and federal agencies. The eGuardian system is a spin-off of a similar but classified tool called Guardian that has been used inside the FBI, and shared with vetted partners since 2005.[115]

Throughout its history, the FBI has been the subject of many controversies, both at home and abroad.

Specific practices include:

.jpg/440px-Gillian_Anderson_&_David_Duchovny_(9344570889).jpg)

The FBI has been frequently depicted in popular media since the 1930s. The bureau has participated to varying degrees, which has ranged from direct involvement in the creative process of film or TV series development, to providing consultation on operations and closed cases.[137] A few of the notable portrayals of the FBI on television are the series The X-Files, which started in 1993 and concluded its eleventh season in early 2018, and concerned investigations into paranormal phenomena by five fictional special agents, and the fictional Counter Terrorist Unit (CTU) agency in the TV drama 24, which is patterned after the FBI Counterterrorism Division.

The 1991 movie Point Break depicts an undercover FBI agent who infiltrated a gang of bank robbers. The 1997 movie Donnie Brasco is based on the true story of undercover FBI agent Joseph D. Pistone infiltrating the Mafia. The 2005–2020 television series Criminal Minds, that follows the team members of the FBI's Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU) in the pursuit of serial killers. The 2017 TV series Riverdale where one of the main characters is an FBI agent. The 2015 TV series Quantico, titled after the location of the Bureau's training facility, deals with probationary and special agents, not all of whom, within the show's format, may be fully reliable or even trustworthy.

The 2018 series FBI, set in NYC that follows the personal and professional lives of the agents assigned to 26 Federal Plaza (NYC FBI field office). FBI's first spin-off titled FBI: Most Wanted (2019), follows the FBI's Fugitive Task Force in chasing down the US's most wanted criminals, and the second spin-off, FBI: International (2021), follows the FBI's International Fly Team that goes where ever they are needed in the world to protect the US's interests.

In my last annual report I called attention to the fact that this department was obliged to call upon the Treasury Department for detective service, and had, in fact, no permanent executive force directly under its orders. Through the prohibition of its further use of the Secret Service force, contained in the Sundry Civil Appropriation Act, approved May 27, 1908, it became necessary for the department to organize a small force of special agents of its own. Although such action was involuntary on the part of this department, the consequences of the innovation have been, on the whole, moderately satisfactory. The Special Agents, placed as they are under the direct orders of the Chief Examiner, who receives from them daily reports and summarizes these each day to the Attorney General, are directly controlled by this department, and the Attorney General knows or ought to know, at all times what they are doing and at what cost.

The only personally owned handguns now on the approved list are the Glock 21 (full-size .45 ACP), the Glock 26 (sub-compact 9 mm) and the 27 (sub-compact .40 S&W).

Also in the '80s, HRT adopted the Browning Hi-Power. The first Hi-Powers were customized by Wayne Novak and later ones by the FBI gunsmiths at Quantico. They were popular with the 'super SWAT' guys, and several hesitated to give them up when they were replaced by .45 ACP single-action pistols, the first ones built by Les Baer, which used high-capacity Para Ordnance frames. Later, Springfield Armory's 'Bureau Model' replaced the Baer guns. Field SWAT teams were also issued .45s, and most still use them.

Originally developed as a consumer-friendly option for the FBI contract Professional Model 1911, the TRP™ family provides high-end custom shop features in a production class pistol.

Every new RO Elite series pistol is clad in the same Black-T® treatment specified on Springfield Armory 1911s built for the FBI's regional SWAT and Hostage Rescue Teams.