Салоники ( / ˌ θ ɛ s ə l ə ˈ n iː k i / ; греческий : Θεσσαλονίκη [ θesaloˈnici] ), также известный как(англ.Thessalonica , ˌ θ ɛ s ə l ə ˈ n aɪ k ə , ˌ θ ɛ s ə ˈ l ɒ n ɪ k ə / ) ,Салоники,СалоникиилиСалоники( англ. Salonica , ˌ s ə ˈ l ɒ n ɪ k ə , ˌ s æ l ə ˈ n iː k ə / ) — второй по величине город вГреции, с населением чуть более одного миллиона человек в егостоличном регионе, а такжестолица географического региона Македония,административногорайонаЦентральнаяМакедонияиДецентрализованнойадминистрацииМакедониии Фракии.[7][8]Он также известен по-греческикак «η Συμπρωτεύουσα» (i Symprotévousa), буквально «со-столица»,[9]что является ссылкой на его исторический статус какΣυμβασιλεύουσα(Symvasilévousa) или «соправляющегося» города Византийскойимпериинаряду сКонстантинополем.[10]

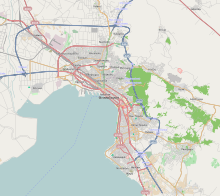

Салоники расположены на заливе Термаикос , в северо-западной части Эгейского моря . На западе он ограничен дельтой реки Аксиос . Население муниципалитета Салоники , исторического центра, в 2021 году составляло 319 045 человек [5] , в то время как в столичном регионе Салоники проживало 1 006 112 человек, а в регионе — 1 092 919 человек [4] [3] Это второй по величине экономический, промышленный, торговый и политический центр Греции, а также крупный транспортный узел для Греции и юго-восточной Европы, в частности через порт Салоники [11] . Город славится своими фестивалями, мероприятиями и яркой культурной жизнью в целом. [12] Ежегодно проводятся такие мероприятия, как Международная ярмарка в Салониках и Международный кинофестиваль в Салониках . Салоники были Европейской молодежной столицей 2014 года . Главный университет города, Университет Аристотеля , является крупнейшим в Греции и на Балканах . [13]

Город был основан в 315 г. до н. э. Кассандром Македонским , который назвал его в честь своей жены Фессалоники , дочери Филиппа II Македонского и сестры Александра Великого . Он был построен в 40 км к юго-востоку от Пеллы , столицы Королевства Македонии . Важный мегаполис римского периода, Салоники были вторым по величине и богатейшим городом Византийской империи . Он был завоеван османами в 1430 году и оставался важным морским портом и многоэтническим мегаполисом в течение почти пяти веков турецкого правления , с церквями, мечетями и синагогами, сосуществующими бок о бок. С 16 по 20 век это был единственный город с еврейским большинством в Европе . 8 ноября 1912 года Салоники перешли от Османской империи к Королевству Греции. В Салониках представлена византийская архитектура , в том числе многочисленные палеохристианские и византийские памятники , объект Всемирного наследия , а также несколько римских , османских и сефардских еврейских построек.

В 2013 году журнал National Geographic включил Салоники в число лучших туристических направлений мира, [14] а в 2014 году журнал Financial Times FDI (Foreign Direct Investments) объявил Салоники лучшим европейским городом среднего размера будущего для человеческого капитала и образа жизни. [15] [16]

Первоначальное название города было Θεσσαλονίκη Thessaloníkē . Он был назван в честь принцессы Фессалоники Македонской , единокровной сестры Александра Великого , чье имя означает «Фессалийская победа», от Θεσσαλός Thessalos и Νίκη «победа» ( Ника ), в честь победы македонцев в битве при Крокус-Филд (353/352 до н. э.).

Встречаются также незначительные варианты, в том числе Θετταλονίκη Thettaloníkē , [17] [18] Θεσσαλονίκεια Thessalonikeia , [19] Θεσσαλονείκη Thessaloneíkē и Θεσαλονισκέων Салоникеон . [20] [21]

Название Σαλονίκη Салоники впервые упоминается в греческом языке в « Хронике Мореи» (XIV в.) и часто встречается в народных песнях , но, должно быть, оно возникло раньше, поскольку аль-Идриси уже в XII в. называл его Салуником . Это основа названия города на других языках: Солѹнъ ( Solunŭ ) на старославянском , סאלוניקו [22] [23] ( Saloniko ) на иудео-испанском (שאלוניקי до 19 века [23] ) סלוניקי ( Saloniki ) на иврите , Selenik на албанском языке , سلانیك ( Selânik ) на османском турецком и Selanik на современном турецком , Salonicco на итальянском , Solun или Солун на местных и соседних южнославянских языках , Салоники ( Saloníki ) на русском , Sãrunã на арумынском [24] и Săruna на мегленорумынском [25 ]

На английском языке город может называться Thessaloniki, Salonika, Thessalonica, Salonica, Thessalonika, Saloniki, Thessalonike или Thessalonice. В печатных текстах наиболее распространенным названием и написанием до начала 20-го века было Thessalonica, что соответствовало латинскому названию; на протяжении большей части 20-го века это было Salonika. Примерно к 1985 году наиболее распространенным отдельным названием стало Thessaloniki. [26] [27] Формы с латинским окончанием -a, взятые вместе, остаются более распространенными, чем формы с фонетическим греческим окончанием -i , и гораздо более распространенными, чем древняя транслитерация -e . [28]

Салоники были возрождены как официальное название города в 1912 году, когда он присоединился к Королевству Греции во время Балканских войн . [29] В местной речи название города обычно произносится с темным и глубоким L , характерным для акцента современного македонского диалекта греческого языка . [30] [31] Название часто сокращается до Θεσ/νίκη . [ необходима цитата ]

Город был основан около 315 г. до н. э. царем Кассандром Македонским на месте древнего города Терма и 26 других местных деревень или около него. [32] [33] Он назвал его в честь своей жены Фессалоники , [34] единокровной сестры Александра Великого и принцессы Македонии как дочери Филиппа II . Во времена Македонского царства город сохранил свою собственную автономию и парламент [35] и превратился в самый важный город в Македонии. [34]

Спустя двадцать лет после падения Македонского царства в 168 г. до н. э., в 148 г. до н. э. Салоники стали столицей римской провинции Македония . [36] Салоники стали свободным городом Римской республики при Марке Антонии в 41 г. до н. э. [34] [37] Он вырос и стал важным торговым узлом, расположенным на Виа Эгнатиа , [38] дороге, соединяющей Диррахий с Византией , [39] которая способствовала торговле между Салониками и крупными центрами торговли, такими как Рим и Византия . [40] Салоники также находятся в южном конце главного маршрута с севера на юг через Балканы вдоль долин рек Морава и Аксиос , тем самым связывая Балканы с остальной Грецией. [41] Город стал столицей одного из четырех римских округов Македонии; [38]

Во времена Римской империи, около 50 г. н. э., Салоники также были одним из ранних центров христианства ; во время своего второго миссионерского путешествия апостол Павел посетил главную синагогу этого города в три субботы и посеял семена для первой христианской церкви в Салониках. Позже Павел написал письма в новую церковь в Салониках, причем два письма к церкви под его именем появляются в библейском каноне как Первое и Второе послание к Фессалоникийцам . Некоторые ученые считают, что Первое послание к Фессалоникийцам является первой написанной книгой Нового Завета . [42]

В 306 году нашей эры Салоники обрели святого покровителя, Святого Димитрия , христианина, которого, как говорят, Галерий казнил. Большинство ученых согласны с теорией Ипполита Делеэ о том, что Димитрий не был уроженцем Салоник, но его почитание было перенесено в Салоники, когда они заменили Сирмий в качестве главной военной базы на Балканах. [43] Базиличная церковь , посвященная Святому Димитрию, Хагиос Димитриос , была впервые построена в пятом веке нашей эры и теперь является объектом Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО .

Когда Римская империя была разделена на тетрархию , Салоники стали административной столицей одной из четырех частей империи при Галерии Максимиане Цезаре , [44] [45] где Галерий заказал императорский дворец, новый ипподром , триумфальную арку и мавзолей , среди других сооружений. [45] [46] [47]

В 379 году, когда римская префектура Иллирик была разделена между Восточной и Западной Римской империями, Салоники стали столицей новой префектуры Иллирик. [38] В следующем году Эдикт Салоники сделал христианство государственной религией Римской империи . [48] В 390 году войска под командованием римского императора Феодосия I устроили резню против жителей Фессалоник , которые подняли восстание против задержания любимого возничего. К моменту падения Рима в 476 году Салоники были вторым по величине городом Восточной Римской империи . [40]

_(4._Jhdt.)_(47052790724).jpg/440px-Thessaloniki,_Nördliche_Stadtmauer_(Τείχη_της_Θεσσαλονίκης)_(4._Jhdt.)_(47052790724).jpg)

С первых лет Византийской империи Салоники считались вторым городом в империи после Константинополя [49] [ 50] [51] как по богатству, так и по размеру [49] , с населением в 150 000 человек в середине XII века. [52] Город сохранял этот статус до перехода под контроль Венеции в 1423 году. В XIV веке население города превышало 100 000–150 000 человек [53] [54] [55], что делало его больше, чем Лондон того времени. [56]

В течение шестого и седьмого веков территория вокруг Салоник была захвачена аварами и славянами, которые безуспешно осаждали город несколько раз, как повествуется в Чудесах Святого Димитрия . [57] Традиционная историография утверждает, что многие славяне поселились в глубинке Салоник; [58] однако современные ученые считают, что эта миграция была в гораздо меньших масштабах, чем считалось ранее. [58] [59] В девятом веке византийские миссионеры Кирилл и Мефодий , оба уроженцы города, создали первый литературный язык славян, старославянский , скорее всего, основанный на славянском диалекте, использовавшемся в глубинке их родного города. [60] [61] [62] [63] [64]

Морская атака, возглавляемая византийскими новообращенными в ислам (включая Льва Триполийского ) в 904 году, привела к разграблению города . [65]

Экономическая экспансия города продолжалась в течение XII века, поскольку правление императоров из династии Комнинов расширило византийский контроль на север. Салоники вышли из-под власти Византии в 1204 году, [66] когда Константинополь был захвачен войсками Четвертого крестового похода и включил город и его окрестности в Королевство Фессалоники [67] — которое затем стало крупнейшим вассалом Латинской империи . В 1224 году Королевство Фессалоники было захвачено деспотатом Эпира , остатком бывшей Византийской империи, под руководством Феодора Комнина Дуки , который короновал себя императором, [68] и город стал столицей недолговечной Империи Фессалоники . [68] [69] [70] [71] Однако после его поражения при Клокотнице в 1230 году [68] [72] Фессалоникийская империя стала вассальным государством Второго Болгарского царства , пока не была снова восстановлена в 1246 году, на этот раз Никейской империей . [68]

В 1342 году [73] в городе возникла Коммуна зелотов , антиаристократическая партия, сформированная из моряков и бедняков, [74] которую в настоящее время называют социально-революционной. [73] Город был практически независим от остальной части Империи, [73] [74] [75], поскольку имел собственное правительство, форму республики. [73] Движение зелотов было свергнуто в 1350 году, и город воссоединился с остальной частью Империи. [73]

Захват Галлиполи османами в 1354 году положил начало быстрой турецкой экспансии на юге Балкан , проводимой как самими османами , так и полунезависимыми турецкими воинами- гази . К 1369 году османы смогли завоевать Адрианополь (современный Эдирне ), который стал их новой столицей до 1453 года . [76] Сама Фессалоника, которой правил Мануил II Палеолог (правил в 1391–1425 годах), сдалась после длительной осады в 1383–1387 годах , вместе с большей частью восточной и центральной Македонии, войскам султана Мурада I. [ 77] Первоначально сдавшимся городам была предоставлена полная автономия в обмен на уплату подушного налога харадж . Однако после смерти императора Иоанна V Палеолога в 1391 году Мануил II сбежал из-под стражи османов и отправился в Константинополь, где был коронован императором, став преемником своего отца. Это разозлило султана Баязида I , который опустошил оставшиеся византийские территории, а затем обратился к Хрисополису, который был взят штурмом и в значительной степени разрушен. [78] Фессалоники также снова подчинились османскому правлению в это время, возможно, после непродолжительного сопротивления, но с ними обошлись более снисходительно: хотя город был полностью взят под контроль османов, христианское население и церковь сохранили большую часть своих владений, а город сохранил свои учреждения. [79] [80]

Фессалоники оставались в руках Османской империи до 1403 года, когда император Мануил II встал на сторону старшего сына Баязида Сулеймана в борьбе за престол Османской империи , которая разразилась после сокрушительного поражения и пленения Баязида в битве при Анкаре против Тамерлана в 1402 году. В обмен на свою поддержку в Галлиполийском договоре византийский император добился возвращения Фессалоники, части ее внутренних районов, полуострова Халкидики и прибрежного региона между реками Стримон и Пиней . [81] [82] Фессалоники и окружающий регион были переданы в качестве автономного удела Иоанну VII Палеологу . После его смерти в 1408 году его сменил третий сын Мануила, деспот Андроник Палеолог , которым руководил Деметриос Леонтарес до 1415 года. Фессалоники пережили период относительного мира и процветания после 1403 года, поскольку турки были заняты своей собственной гражданской войной , но подверглись нападению со стороны соперничающих османских претендентов в 1412 году ( Мусы Челеби [83] ) и 1416 году (во время восстания Мустафы Челеби против Мехмеда I [84] ). [85] [86] После окончания османской гражданской войны турецкое давление на город снова начало усиливаться. Так же, как и во время осады 1383–1387 годов, это привело к резкому разделению мнений внутри города между фракциями, поддерживающими сопротивление, при необходимости с западной помощью, или подчинение османам. [87]

В 1423 году деспот Андроник Палеолог уступил его Венецианской республике в надежде, что он сможет защитить его от османов, осаждавших город . Венецианцы удерживали Салоники, пока они не были захвачены османским султаном Мурадом II 29 марта 1430 года. [88]

Когда султан Мурад II захватил Салоники и разграбил их в 1430 году, [89] современные отчеты подсчитали, что около одной пятой населения города было обращено в рабство. [90] Османская артиллерия использовалась для обеспечения захвата города и обхода его двойных стен. [89] После завоевания Салоник некоторые из его жителей бежали, [91] включая таких интеллектуалов, как Феодор Газа «Фессалоникский» и Андроник Каллист . [92] Однако смена суверенитета от Византийской империи к Османской не повлияла на престиж города как крупного имперского города и торгового центра. [93] [94] Салоники и Смирна , хотя и были меньше по размеру, чем Константинополь , были важнейшими торговыми центрами Османской империи. [93] Салоники были важны в основном в области судоходства , [93] но также и в производстве, [94] при этом большинство торговцев города были евреями . [93]

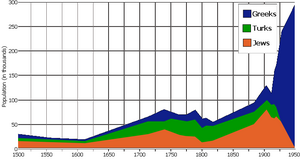

В период Османской империи население города, состоящее из османских мусульман (включая лиц турецкого происхождения, а также албанских мусульман , болгарских мусульман , особенно помаков и греков-мусульман новообращенного происхождения) и мусульманских цыган, таких как Sepečides Romani, существенно возросло. Согласно переписи 1478 года, в Селянике ( османский турецкий : سلانیك ), как город стал называться на османском турецком языке, было 6094 христианских православных домохозяйства , 4320 мусульманских и несколько католических. В переписи не было зарегистрировано ни одного еврея, что говорит о том, что последующий приток еврейского населения не был связан [96] с уже существующей общиной романиотов . [97] Однако вскоре после рубежа XV-XVI веков около 20 000 сефардских евреев иммигрировали в Грецию с Пиренейского полуострова после их изгнания из Испании по указу Альгамбры 1492 года . [98] К 1500 году число домохозяйств выросло до 7986 христианских, 8575 мусульманских и 3770 еврейских. К 1519 году число сефардских еврейских домохозяйств составило 15 715, 54% населения города. Некоторые историки считают, что приглашение Османским режимом еврейских поселений было стратегией, направленной на предотвращение доминирования христианского населения в городе. [99] Город стал как крупнейшим еврейским городом в мире, так и единственным городом с еврейским большинством в мире в 16 веке. В результате Салоники привлекали преследуемых евреев со всего мира. [100]

Салоники были столицей санджака Селаник в более широком эялете Румели (Балканы) [101] до 1826 года, а затем столицей эялета Селаник (после 1867 года вилайет Селаник ). [102] [103] Он состоял из санджаков Селаник, Серрес и Драма между 1826 и 1912 годами. [104]

С началом Греческой войны за независимость весной 1821 года губернатор Юсуф-бей заключил в своей штаб-квартире более 400 заложников. 18 мая, когда Юсуф узнал о восстании в деревнях Халкидики , он приказал убить половину своих заложников у него на глазах. Мулла Салоник Хайрйуллах дает следующее описание ответных действий Юсуфа: «Каждый день и каждую ночь на улицах Салоник вы ничего не слышите, кроме криков и стонов. Кажется, что Юсуф-бей, Еничери Агаси, Субаши, хока и улемы — все они сошли с ума». [105] Греческая община города восстановилась только к концу столетия. [106]

Салоники также были оплотом янычар , где обучались новички-янычары. В июне 1826 года регулярные османские солдаты атаковали и разрушили базу янычар в Салониках, убив также более 10 000 янычар, событие, известное как Благоприятный инцидент в истории Османской империи. [107] В 1870–1917 годах, благодаря экономическому росту, население города увеличилось на 70%, достигнув 135 000 человек в 1917 году. [108]

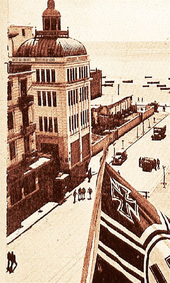

Последние несколько десятилетий османского контроля над городом были эпохой возрождения, особенно в плане инфраструктуры города. Именно в это время османская администрация города приобрела «официальное» лицо с созданием Дома правительства [109], в то время как ряд новых общественных зданий были построены в эклектичном стиле , чтобы проецировать европейский облик как Салоников, так и Османской империи. [109] [110] Городские стены были снесены между 1869 и 1889 годами, [111] попытки планового расширения города были очевидны еще в 1879 году, [112] первое трамвайное сообщение началось в 1888 году , [113] а улицы города были освещены электрическими фонарными столбами в 1908 году. [114] В 1888 году Восточная железная дорога соединила Салоники с Центральной Европой по железной дороге через Белград и с Монастиром в 1893 году, в то время как железнодорожная станция Салоники-Стамбул соединила его с Константинополем в 1896 году. [112]

Мустафа Кемаль Ататюрк , основатель современной Турецкой Республики , родился в Салониках (тогда известных как Селаник на османском турецком языке) в 1881 году. Место его рождения на улице Ислахане Джаддеси (ныне улица Апостолоу, 24) в настоящее время является Музеем Ататюрка и является частью комплекса турецкого консульства. [115]

В начале 20 века Салоники были в центре радикальной деятельности различных групп: Внутренняя македонская революционная организация , основанная в 1897 году, [116] и Греческий македонский комитет , основанный в 1903 году. [117] В 1903 году болгарская анархистская группа, известная как Лодочники Салоник, заложила бомбы в нескольких зданиях в Салониках, включая Османский банк , при некоторой помощи со стороны IMRO. Греческое консульство в Османских Салониках (ныне Музей борьбы за Македонию ) служило центром операций греческих партизан.

В этот период и с XVI века еврейский элемент Салоник был наиболее доминирующим; это был единственный город в Европе, где евреи составляли большинство от общей численности населения. [118] Город был этнически разнообразным и космополитичным . В 1890 году его население возросло до 118 000 человек, 47% из которых были евреями, за ними следовали турки (22%), греки (14%), болгары (8%), цыгане (2%) и другие (7%). [119] К 1913 году этнический состав города изменился, так что население составляло 157 889 человек, из которых евреи составляли 39%, за ними снова следовали турки (29%), греки (25%), болгары (4%), цыгане (2%) и другие (1%). [120] Здесь исповедовали множество различных религий и говорили на многих языках, включая иудео-испанский — диалект испанского языка, на котором говорили евреи города.

Салоники также были центром деятельности младотурок , политического реформаторского движения, целью которого была замена абсолютной монархии Османской империи конституционным правительством. Младотурки начинали как подпольное движение, пока, наконец, в 1908 году они не начали младотурецкую революцию в городе Салоники, что привело к тому, что они получили контроль над Османской империей и положили конец власти османских султанов. [121] Площадь Элефтериас (Свободы) , где младотурки собрались в начале революции, названа в честь этого события. [122] Первый президент Турции Мустафа Кемаль Ататюрк , родившийся и выросший в Салониках, был членом младотурок в свои солдатские дни и также принимал участие в младотурецкой революции.

Когда началась Первая Балканская война , Греция объявила войну Османской империи и расширила свои границы. Когда Элефтериоса Венизелоса , премьер-министра того времени, спросили, должна ли греческая армия двинуться в сторону Салоник или Монастира (ныне Битола , Республика Северная Македония ), Венизелос ответил: « Θεσσαλονίκη με κάθε κόστος! » ( Салоники, любой ценой! ). [123] С превосходящей численностью Османской армией, ведущей арьергардный бой против хорошо подготовленных греческих сил в Енидже , болгарскими войсками, наступавшими поблизости, и Османской военно-морской базой в Салониках, блокированной греческим флотом, генерал Хасан Тахсин-паша вскоре понял, что оборонять город стало невыгодно. Потопление османского броненосца Feth-i Bülend в гавани Салоников 31 октября [18 октября по старому стилю] 1912 года, хотя и было незначительным с военной точки зрения, еще больше подорвало моральный дух османов. Поскольку и Греция, и Болгария хотели Салоники, османский гарнизон города вступил в переговоры с обеими армиями. [124] 8 ноября 1912 года (26 октября по старому стилю ), в день памяти покровителя города, Святого Димитрия , греческая армия приняла капитуляцию османского гарнизона в Салониках. [125] Болгарская армия прибыла на следующий день после сдачи города Греции, и Хасан Тахсин-паша, командующий обороной города, сказал болгарским чиновникам, что «у меня есть только одни Салоники, которые я сдал». [124] После Второй Балканской войны Салоники и остальная часть греческой части Македонии были официально присоединены к Греции по Бухарестскому договору в 1913 году. [126] 18 марта 1913 года Георг I Греческий был убит в городе Александросом Схинасом . [127]

В 1915 году, во время Первой мировой войны , крупные экспедиционные силы союзников создали базу в Салониках для операций [128] против прогерманской Болгарии. [129] Это привело к созданию Македонского фронта , также известного как Салоникский фронт. [130] [131] А временный госпиталь, управляемый Шотландскими женскими госпиталями для дипломатической службы , был создан на заброшенной фабрике. В 1916 году провенизелистские греческие офицеры и гражданские лица при поддержке союзников подняли восстание, [132] создав просоюзное [133] временное правительство под названием « Временное правительство национальной обороны » [132] [134] , которое контролировало «Новые земли» (земли, которые были получены Грецией в Балканских войнах , большая часть Северной Греции, включая Греческую Македонию, Северное Эгейское море , а также остров Крит ); [132] [134] официальное правительство короля в Афинах , «Государство Афин», [132] контролировало «Старую Грецию» [132] [134] , которая была традиционно монархической. Государство Салоники было упразднено с объединением двух противоборствующих греческих правительств под руководством Венизелоса после отречения короля Константина в 1917 году . [129] [134]

30 декабря 1915 года австрийский воздушный налет на Салоники встревожил многих мирных жителей города и убил по меньшей мере одного человека, а в ответ базирующиеся там войска союзников арестовали немецких, австрийских, болгарских и турецких вице-консулов , а также их семьи и иждивенцев и посадили их на линкор, а войска разместили в зданиях своих консульств в Салониках. [135]

Большая часть старого центра города была уничтожена Великим пожаром в Салониках 1917 года , который начался случайно из-за пожара на кухне, оставшегося без присмотра 18 августа 1917 года. [136] Огонь охватил центр города, оставив 72 000 человек без крова; согласно отчету Паллиса, большинство из них были евреями (50 000). Многие предприятия были разрушены, в результате чего 70% населения остались без работы. [136] Две церкви и множество синагог и мечетей были утрачены. Более четверти от общей численности населения, составлявшего приблизительно 271 157 человек, остались без крова. [136] После пожара правительство запретило быстрое восстановление, чтобы реализовать новую перепланировку города в соответствии с городским планом в европейском стиле [10], подготовленным группой архитекторов, включая британца Томаса Моусона , и возглавляемым французским архитектором Эрнестом Эбраром . [136] Стоимость недвижимости упала с 6,5 миллионов греческих драхм до 750 000. [137]

После поражения Греции в греко-турецкой войне и во время распада Османской империи произошел обмен населением между Грецией и Турцией. [133] Более 160 000 этнических греков, депортированных из бывшей Османской империи , в частности греки из Малой Азии [138] и Восточной Фракии , были переселены в город, [133] изменив его демографическую ситуацию. Кроме того, многие мусульмане города, включая османских греков-мусульман , были депортированы в Турцию, в количестве около 20 000 человек. [139] Это сделало греческий элемент доминирующим, [140] в то время как еврейское население было сокращено до меньшинства впервые с 16-го века. [141]

Это было частью общего процесса современной эллинизации, которая затронула почти все меньшинства в Греции, превратив регион в очаг этнического национализма. [142]

Во время Второй мировой войны Салоники подверглись сильной бомбардировке со стороны фашистской Италии (только в ноябре 1940 года погибло 232 человека, было ранено 871 человек и было повреждено или разрушено более 800 зданий) [144] , и, поскольку итальянцы потерпели неудачу в своем вторжении в Грецию , город пал под нацистской Германией 8 апреля 1941 года [145] и попал под немецкую оккупацию. Вскоре нацисты заставили еврейских жителей переселиться в гетто рядом с железной дорогой, а 15 марта 1943 года начали депортацию евреев города в концентрационные лагеря Освенцим и Берген-Бельзен . [146] [147] [148] Большинство из них были немедленно убиты в газовых камерах . Из 45 000 евреев, депортированных в Освенцим, выжили только 4%. [149] [150]

Во время речи в Рейхстаге Гитлер заявил, что целью его балканской кампании было помешать союзникам создать «новый македонский фронт», как это было во время Первой мировой войны. Важность Салоник для нацистской Германии можно продемонстрировать тем фактом, что изначально Гитлер планировал включить их непосредственно в нацистскую Германию [151] , а не отдать под контроль марионеточного государства, такого как Греческое государство или союзника Германии (Салоники были обещаны Югославии в качестве награды за присоединение к Оси 25 марта 1941 года). [152]

Так как это был первый крупный город в Греции, который пал под натиском оккупационных сил, в Салониках была сформирована первая греческая группа сопротивления (под названием Ελευθερία , Elefthería , «Свобода») [153], а также первая антинацистская газета на оккупированной территории в Европе [154] , также под названием Eleftheria . В Салониках также находился военный лагерь, переоборудованный в концентрационный лагерь, известный на немецком языке как «Konzentrationslager Pavlo Mela» ( концентрационный лагерь Павлоса Меласа ) [155] , где члены сопротивления и другие антифашисты [155] содержались либо для уничтожения, либо для отправки в другие концентрационные лагеря. [155] В сентябре 1943 года немцы создали в городе транзитный лагерь Дулаг 410 для итальянских военных интернированных . [156] 30 октября 1944 года, после боев с отступающей немецкой армией и охранными батальонами Пулоса , силы ЭЛАС вошли в Салоники как освободители во главе с Маркосом Вафиадисом (который не подчинился приказу руководства ЭЛАС в Афинах не входить в город). В городе прошли празднования и демонстрации в поддержку ЭАМ. [157] [158] На референдуме о монархии 1946 года большинство местных жителей проголосовали за республику, в отличие от остальной Греции. [159]

После войны Салоники были перестроены с масштабным развитием новой инфраструктуры и промышленности в течение 1950-х, 1960-х и 1970-х годов. Многие из его архитектурных сокровищ все еще сохраняются, добавляя ценность городу как туристическому направлению, в то время как несколько ранних христианских и византийских памятников Салоников были добавлены в список Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО в 1988 году. [160] В 1997 году Салоники были отмечены как Европейская столица культуры , [161] спонсируя мероприятия по всему городу и региону. Агентство, созданное для надзора за культурными мероприятиями того 1997 года, все еще существовало к 2010 году. [162] В 2004 году город принимал ряд футбольных мероприятий в рамках летних Олимпийских игр 2004 года . [163]

Сегодня Салоники стали одним из важнейших торговых и деловых центров в Юго-Восточной Европе , с его портом, портом Салоники, являющимся одним из крупнейших в Эгейском море и облегчающим торговлю во всех балканских внутренних районах. [11] 26 октября 2012 года город отпраздновал свое столетие с момента присоединения к Греции. [164] Город также является одним из крупнейших студенческих центров в Юго-Восточной Европе, принимает самое большое количество студентов в Греции и был Европейской молодежной столицей в 2014 году. [165] [166]

Салоники расположены в 502 километрах (312 милях) к северу от Афин .

Городская территория Салоников простирается более чем на 30 километров (19 миль) от Ореокастро на севере до Терми на юге в направлении Халкидики .

Салоники расположены на северном краю залива Термаикос на его восточном побережье и ограничены горой Хортиатис на юго-востоке. Его близость к внушительным горным хребтам, холмам и линиям разломов, особенно на юго-востоке, исторически сделала город подверженным геологическим изменениям.

Со времен Средневековья Салоники подвергались сильным землетрясениям , в частности, в 1759, 1902, 1978 и 1995 годах. [167] 19–20 июня 1978 года город пережил серию мощных землетрясений , магнитудой 5,5 и 6,5 баллов по шкале Рихтера . [168] [169] Подземные толчки нанесли значительный ущерб ряду зданий и древних памятников, [168] но город выдержал катастрофу без каких-либо серьезных проблем. [169] Один многоквартирный дом в центре Салоников рухнул во время второго землетрясения, в результате чего погибло много людей, а общее число погибших достигло 51. [168] [169]

Климат Салоников является переходным, лежащим на периферии нескольких климатических зон. Согласно классификации климата Кеппен , в городе в целом холодный полузасушливый климат ( BSk ), в то время как жаркий полузасушливый климат ( BSh ) находится в центре. Средиземноморское ( Csa ) и влажное субтропическое ( Cfa ) влияние также обнаруживается в климате города. [170] [171] Горный хребет Пинд вносит большой вклад в в целом сухой климат области, существенно высушивая западные ветры. [172] Фактически, станция Международной ярмарки в Салониках Национальной обсерватории Афин является самой северной станцией в мире с жарким полузасушливым климатом ( BSh ). [173]

Зимы довольно сухие, с редкими утренними заморозками. Снегопады случаются более или менее каждую зиму, но снежный покров не держится более нескольких дней. В самые холодные зимы температура может опускаться до −10 °C (14 °F). [174] Рекордно минимальная температура в Салониках составила −14 °C (7 °F). [175] В среднем в Салониках морозы (температура ниже нуля) наблюдаются 32 дня в году, [174] хотя это менее распространено вблизи центра города из-за эффекта городского острова тепла , который характерен для города и более выражен в зимние месяцы. [176] Туманные дни случаются редко, примерно 17 дней в году, в основном осенью и зимой. [177] Самый холодный месяц года в центре Салоник — январь, со средней 24-часовой температурой 8 °C (46 °F). [178] В городе также довольно ветрено в зимние месяцы: в январе и феврале средняя скорость ветра составляет около 11 км/ч (7 миль/ч). [174]

Лето в Салониках жаркое и умеренно сухое. [174] Максимальные температуры обычно поднимаются выше 30 °C (86 °F), [174] но они редко превышают 40 °C (104 °F); [174] в то время как среднее количество дней, когда температура выше 32 °C (90 °F), составляет 32. [174] Как правило, морской бриз, дующий с залива Термаикос, помогает смягчить температуру города. [179] Максимальная зарегистрированная температура в городе составила 44 °C (111 °F). [174] [175] Летом иногда выпадают дожди, в основном во время гроз, в то время как волны тепла случаются спорадически, хотя немногие из них бывают интенсивными. [180] Самые жаркие месяцы года в центре Салоников — июль и август, со средней 24-часовой температурой около 28,0 °C (82 °F). [178]

В 2021 году Европейская комиссия раскритиковала Грецию за неспособность обуздать постоянно высокий уровень загрязнения воздуха в Салониках. [181]

Согласно реформе Калликратиса , по состоянию на 1 января 2011 года городской район Салоники ( греческий : Πολεοδομικό Συγκρότημα Θεσσαλονίκης ), который составляет «Город Салоники», состоит из шести самоуправляющихся муниципалитетов ( греческий : Δήμο ). ι ) и одно муниципальное образование ( греческий : Δημοτική ενότητα ). Муниципалитеты , входящие в городскую зону Салоники, — это Салоники (городской центр и крупнейший по численности населения), Каламария , Неаполи-Сикиес , Павлос Мелас , Корделио-Эвосмос , Амбелокипи-Менемени , а также муниципальные единицы Пилеа и Панорама. , часть муниципалитета Пилеа-Хортиатис . [3] До реформы Калликратиса городская территория Салоников состояла из в два раза большего количества муниципалитетов, значительно меньших по размеру, что создавало бюрократические проблемы. [192]

Муниципалитет Салоники ( греч . Δήμος Θεσαλονίκης ) является вторым по численности населения в Греции после Афин , с постоянным населением 317 778 человек [5] (в 2021 году) и площадью 19,307 квадратных километров (7,454 квадратных миль). Муниципалитет образует ядро городской зоны Салоники , с его центральным районом (городским центром), называемым Кентро , что означает «центр» или «центр города». [193]

Первый мэр города, Осман Саит Бей, был назначен, когда институт мэра был открыт в Османской империи в 1912 году. Действующий мэр - Стелиос Ангелудис. В 2011 году бюджет муниципалитета Салоники составил €464,33 млн. [194] , а бюджет 2012 года составил €409,00 млн. [195]

Салоники — второй по величине город Греции. Это влиятельный город для северных частей страны, столица региона Центральная Македония и региональной единицы Салоники . Министерство Македонии и Фракии также находится в Салониках, поскольку город является фактической столицей греческого региона Македония . [ необходима цитата ]

Каждый год премьер-министр Греции традиционно объявляет политику своей администрации по ряду вопросов, таких как экономика, на открытии Международной ярмарки в Салониках . В 2010 году, в первые месяцы греческого долгового кризиса 2010 года , весь кабинет министров Греции собрался в Салониках, чтобы обсудить будущее страны. [196]

В греческом парламенте городская территория Салоников представляет собой 17-местный избирательный округ. По состоянию на греческие законодательные выборы в июне 2023 года крупнейшей партией в Салониках является Новая демократия с 35,28% голосов, за ней следует СИРИЗА (17,52%). [197] В таблице ниже обобщены результаты последних выборов.

Архитектура в Салониках является прямым результатом положения города в центре всех исторических событий на Балканах. Помимо своей торговой значимости, Салоники на протяжении многих веков были военным и административным центром региона, а также транспортным узлом между Европой и Левантом . Купцы, торговцы и беженцы со всей Европы селились в городе. Потребность в коммерческих и общественных зданиях в эту новую эпоху процветания привела к строительству крупных зданий в центре города. В это время в городе были построены банки, большие отели, театры, склады и фабрики. Архитекторы, спроектировавшие некоторые из самых известных зданий города в конце 19-го и начале 20-го века, включают Виталиано Поселли , Пьетро Арригони , Ксенофонт Паионидис , Сальваторе Поселли, Леонардо Дженнари, Эли Модиано, Моше Жак, Жозеф Плейбер, Фредерик Чарно, Эрнст Циллер , Макс Рубенс, Филимон Паионидис, Димитрис Андроникос, Леви Эрнст, Ангелос Сиагас, Александрос Цонис и другие, используя в основном стили эклектизма , модерна и необарокко .

Планировка города изменилась после 1870 года, когда прибрежные укрепления уступили место обширным пирсам, и многие из старейших стен города были снесены, включая те, что окружали Белую башню , которая сегодня является главной достопримечательностью города. Поскольку части ранних византийских стен были снесены, это позволило городу расшириться на восток и запад вдоль побережья. [198]

Расширение площади Элефтериас в сторону моря завершило создание нового коммерческого центра города и в то время считалось одной из самых оживленных площадей города. По мере роста города рабочие переезжали в западные районы из-за их близости к фабрикам и промышленным предприятиям; в то время как средний и высший классы постепенно переезжали из центра города в восточные пригороды, оставляя в основном предприятия. В 1917 году по городу прокатился разрушительный пожар, который неудержимо горел в течение 32 часов. [108] Он уничтожил исторический центр города и большую часть его архитектурного наследия, но проложил путь для современной застройки с более широкими диагональными проспектами и монументальными площадями. [108] [199]

.jpg/440px-Θεσσαλονίκη_2014_-_panoramio_(2).jpg)

После Великого пожара в Салониках 1917 года группа архитекторов и градостроителей, включая Томаса Моусона и Эрнеста Хебрара , французского архитектора, выбрали византийскую эпоху в качестве основы для своих проектов (пере)стройки центра города Салоники. Новый план города включал оси, диагональные улицы и монументальные площади с уличной сеткой , которая бы плавно направляла движение. План 1917 года включал положения о будущем расширении населения и сети улиц и дорог, которая была бы и остается достаточной сегодня. [108] Он содержал участки для общественных зданий и предусматривал восстановление византийских церквей и османских мечетей.

Также называемый историческим центром , он разделен на несколько районов, включая площадь Демократии (площадь Демократии, также известную как Вардарис ), Лададика (где расположено множество развлекательных заведений и таверн), Капани (где находится центральный городской рынок Модиано ), Диагониос , Наварину , Ротонда , Агия София и Ипподром , которые все расположены вокруг самой центральной точки Салоников — площади Аристотеля .

Различные торговые портики вокруг Аристотеля названы в честь прошлого города и исторических личностей города, например, портик Хирша , портик Карассо /Эрму, Пелосов, Коломбо, Леви, Модиано , Морпурго, Мордох, Симха, Кастория, Малакопи, Олимпиос, Эмборон, Роготи, Византио, Татти, Агиу Мина, Карипи и т. д. [200]

В западной части центра города находятся суды Салоников, центральный международный железнодорожный вокзал и порт , а в восточной части находятся два городских университета, Международный выставочный центр Салоников , главный стадион города , археологический и византийский музеи, новая ратуша и центральные парки и сады, а именно ΧΑΝΘ и Педион ту Ареос .

Ано Поли (также называемый Старым городом и буквально Верхним городом ) — район, входящий в список объектов культурного наследия к северу от центра города Салоники, который не пострадал от большого пожара 1917 года и был объявлен объектом Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО благодаря министерским действиям Мелины Меркури в 1980-х годах. Он состоит из самой традиционной части города Салоники, где по-прежнему сохранились небольшие мощеные улочки, старые площади и дома, построенные в старом греческом и османском стиле . Это излюбленное место поэтов, интеллектуалов и богемы Салоников.

Ано Поли также является самой высокой точкой в Салониках и, как таковая, является местом расположения акрополя города, его византийского форта, Гептапиргиона , большой части оставшихся стен города , и со многими из его дополнительных османских и византийских сооружений, которые все еще стоят. С захватом Салоник османами в 1430 году, после длительной осады города с 1422 по 1430 год, османы поселились в Ано Поли. Этот географический выбор был обусловлен более высоким уровнем Ано Поли, что было удобно для контроля остальной части населения на расстоянии, и микроклиматом области, который благоприятствовал лучшим условиям жизни с точки зрения гигиены по сравнению с районами центра.

Сегодня этот район обеспечивает доступ к национальному парку Seich Sou Forest [201] и предлагает панорамный вид на весь город и залив Термаикос . В ясные дни можно также увидеть возвышающуюся на горизонте гору Олимп , расположенную примерно в 100 км (62 милях) через залив.

В состав муниципалитета Салоник, помимо исторического центра и Верхнего города, входят следующие районы: Ксирокрини, Дикастирия (Суды), Ихтиоскала, Палеос Статмос, Лаханокипой, Бехцинари, Панагия Фанеромени, Докса, Саранта Экклисиес, Евангелистрия, Триандрия. , Агиа Триада-Фалиро, Иппократио, Харилау, Аналипси, Депо и Тумба.

В районе Старого железнодорожного вокзала (Palaios Stathmos) началось строительство Музея Холокоста Греции . [202] [203] В этом районе расположены Железнодорожный музей Салоник , Музей водоснабжения и крупные развлекательные заведения города, такие как Milos , Fix , Vilka (которые размещаются в переоборудованных старых фабриках). Железнодорожный вокзал Салоник находится на улице Монастириу.

Другие обширные и плотно застроенные жилые районы — Харилау и Тумба , которые делятся на «Ано Тумпа» и «Като Тумпа». Тумба была названа в честь одноименного холма Тумба, где проводятся обширные археологические исследования. Он был создан беженцами после катастрофы в Малой Азии 1922 года и обмена населением (1923–24). На проспекте Экзохон ( улица Кампань , сегодня проспекты Василиссис Олгас и Василеос Георгиу) до 1920-х годов проживали самые богатые жители города, и в то время это были самые отдаленные пригороды города, с районом, близким к заливу Термаикос , из вилл для отдыха 19 века, которые определяли этот район. [204] [205]

Другие районы более широкой городской территории Салоников — Ампелокипи, Элефтерио — Корделио, Менемени, Эвосмос, Илиуполи, Ставруполи, Никополи, Неаполи, Полихни, Паэглос, Метеора, Агиос Павлос, Каламария, Пилеа и Сикис. Северо-западные Салоники являются домом для Монастыря Лазаристона , расположенного в Ставруполи , который сегодня является одним из важнейших культурных центров города, включая MOMus — Музей современного искусства — Коллекция Костаки и два театра Национального театра Северной Греции . [206] [207]

На северо-западе Салоников существует множество культурных учреждений, таких как театр под открытым небом Маноса Катракиса в Сикисе, Музей эллинизма беженцев в Неаполисе, муниципальный театр и театр под открытым небом в Неаполи и Новый культурный центр Менемени (улица Эллис Алексиу). [208] Ботанический сад Ставруполиса на улице Периклеус включает в себя 1000 видов растений и представляет собой оазис зелени площадью 5 акров (2,0 га). Экологический образовательный центр в Корделио был спроектирован в 1997 году и является одним из немногих общественных зданий биоклиматического дизайна в Салониках. [209]

Северо-запад Салоников образует главный въезд в город Салоники с проспектами Монастириу, Лагкада и 26ис Октовриу, проходящими через него, а также продолжением автомагистрали А1, входящей в центр города Салоники. В этом районе находятся автовокзал Македония InterCity Bus Terminal ( KTEL ), железнодорожная станция Салоники и мемориальное военное кладбище союзников Зейтенлик .

Памятники также были воздвигнуты в честь бойцов греческого Сопротивления , поскольку в этих районах Сопротивление было очень активным: памятник Греческому национальному сопротивлению в Сикиесе, памятник Греческому национальному сопротивлению в Ставруполисе, Статуя борющейся матери на площади Эпталофос и памятник молодым грекам, казненным нацистами 11 мая 1944 года в Ксирокрини. В Эпталофосе 15 мая 1941 года, через месяц после оккупации страны, была основана первая в Греции организация сопротивления «Элефтерия» со своей газетой и первой нелегальной типографией в городе Салоники. [210] [211]

Сегодня юго-восточная часть Салоников в некотором роде стала продолжением центра города: через нее проходят проспекты Мегалу Александру, Георгиу Папандреу (Антеон), Василеос Георгиу, Василиссис Олгас, Дельфон, Константину Караманли (Неа Эгнатия) и Папанастасиу, охватывая район, традиционно называемый Ντεπώ ( Депо , букв. Dépôt), по названию старой трамвайной станции, принадлежавшей французской компании.

Муниципалитет Каламария также расположен на юго-востоке Салоник и изначально был заселен в основном греческими беженцами из Малой Азии и Восточной Фракии после 1922 года. [212] Здесь построены Военно-морское командование Северной Греции и старый королевский дворец (называемый Палатаки ), расположенный на самой западной точке мыса Микро Эмволо .

Из-за важности Салоник в раннехристианский и византийский периоды, город является местом расположения нескольких палеохристианских памятников, которые внесли значительный вклад в развитие византийского искусства и архитектуры по всей Византийской империи , а также в Сербии . [160] Развитие имперской византийской архитектуры и процветание Салоник идут рука об руку, особенно в первые годы Империи, [160] когда город продолжал процветать. Именно в это время был построен комплекс римского императора Галерия , а также первая церковь Святого Димитрия . [160]

К восьмому веку город стал важным административным центром Византийской империи и решал многие балканские вопросы империи . [213] В это время в городе были созданы более примечательные христианские церкви, которые теперь являются частью Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО в Салониках, такие как церковь Святой Екатерины , собор Святой Софии в Салониках , церковь Ахиропиитос , церковь Панагии Халкеон . [ 160] Когда Османская империя взяла под свой контроль Салоники в 1430 году, большинство церквей города были преобразованы в мечети , [160] но сохранились до наших дней. Путешественники, такие как Пол Лукас и Абдул-Меджид I [160], документируют богатство города в христианских памятниках в годы османского контроля над городом.

Церковь Святого Димитрия сгорела во время Великого пожара в Салониках в 1917 году , как и многие другие городские памятники, но была восстановлена. Во время Второй мировой войны город подвергся массированным бомбардировкам, и поэтому многие палеохристианские и византийские памятники Салоник были сильно повреждены. [213] Некоторые из объектов не реставрировались до 1980-х годов. В Салониках больше памятников, внесенных в список Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО, чем в любом другом городе Греции, в общей сложности 15 памятников. [160] Они были включены в список с 1988 года. [160]

_-_panoramio_(2).jpg/440px-Θεσσαλονίκη_2014_(The_Statue_of_Alexander_the_Great)_-_panoramio_(2).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Aristotelous_Square_-_panoramio_(1).jpg)

There are around 150 statues or busts in the city.[214] Probably the most famous one is the equestrian statue of Alexander the Great on the promenade, placed in 1973 and created by sculptor Evangelos Moustakas. An equestrian statue of Constantine I, by sculptor Georgios Dimitriades, is located in Demokratias Square. Other notable statues include that of Eleftherios Venizelos by sculptor Giannis Pappas, Pavlos Melas by Natalia Mela, the statue of Emmanouel Pappas by Memos Makris, Chrysostomos of Smyrna by Athanasios Apartis, Aristotle on Aristotelous Square and such as various creations by George Zongolopoulos.

With the 100th anniversary of the 1912 incorporation of Thessaloniki into Greece, the government announced a large-scale redevelopment programme for the city of Thessaloniki, which aims in addressing the current environmental and spatial problems[215] that the city faces. More specifically, the programme will drastically change the physiognomy of the city[215] by relocating the Thessaloniki International Exhibition Centre and grounds of the Thessaloniki International Fair outside the city centre and turning the current location into a large metropolitan park,[216] redeveloping the coastal front of the city,[216] relocating the city's numerous military camps and using the grounds and facilities to create large parklands and cultural centres;[216] and the complete redevelopment of the harbour and the Lachanokipoi and Dendropotamos districts (behind and near the Port of Thessaloniki) into a commercial business district,[216] with possible highrise developments.[217]

The plan also envisions the creation of new wide avenues in the outskirts of the city[216] and the creation of pedestrian-only zones in the city centre.[216] Furthermore, the program includes plans to expand the jurisdiction of Seich Sou Forest National Park[215] and the improvement of accessibility to and from the Old Town.[215] The ministry has said that the project will take an estimated 15 years to be completed, in 2025.[216]

Part of the plan has been implemented with extensive pedestrianisations within the city centre by the municipality of Thessaloniki and the revitalisation the eastern urban waterfront/promenade, Νέα Παραλία (Néa Paralía, lit. new promenade), with a modern and vibrant design. Its first section opened in 2008, having been awarded as the best public project in Greece of the last five years by the Hellenic Institute of Architecture.[218]

The municipality of Thessaloniki's budget for the reconstruction of important areas of the city and the completion of the waterfront, opened in January 2014, was estimated at €28.2 million (US$39.9 million) for the year 2011 alone.[219]

Thessaloniki rose to economic prominence as a major economic hub in the Balkans during the years of the Roman Empire. The Pax Romana and the city's strategic position allowed for the facilitation of trade between Rome and Byzantium (later Constantinople and now Istanbul) through Thessaloniki by means of the Via Egnatia.[223] The Via Egnatia also functioned as an important line of communication between the Roman Empire and the nations of Asia,[223] particularly in relation to the Silk Road. With the partition of the Roman Empire into East (Byzantine) and West, Thessaloniki became the second-largest city of the Eastern Roman Empire after New Rome (Constantinople) in terms of economic might.[49][223] Under the Empire, Thessaloniki was the largest port in the Balkans.[224] As the city passed from Byzantium to the Republic of Venice in 1423, it was subsequently conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Under Ottoman rule the city retained its position as the most important trading hub in the Balkans.[93] Manufacturing, shipping and trade were the most important components of the city's economy during the Ottoman period,[93] and the majority of the city's trade at the time was controlled by ethnic Greeks.[93] Plus, the Jewish community was also an important factor in the trade sector.[citation needed]

Historically important industries for the economy of Thessaloniki included tobacco (in 1946 35% of all tobacco companies in Greece were headquartered in the city, and 44% in 1979)[225] and banking (in Ottoman years Thessaloniki was a major centre for investment from western Europe, with the Banque de Salonique having a capital of 20 million French francs in 1909).[93]

The service sector accounts for nearly two-thirds of the total labour force of Thessaloniki.[226] Of those working in services, 20% were employed in trade; 13% in education and healthcare; 7.1% in real estate; 6.3% in transport, communications and storage; 6.1% in the finance industry and service-providing organizations; 5.7% in public administration and insurance services; and 5.4% in hotels and restaurants.[226]

The city's port, the Port of Thessaloniki, is one of the largest ports in the Aegean and as a free port, it functions as a major gateway to the Balkan hinterland.[11][227] In 2010, more than 15.8 million tons of products went through the city's port,[228] making it the second-largest port in Greece after Aghioi Theodoroi, surpassing Piraeus. At 273,282 TEUs, it is also Greece's second-largest container port after Piraeus.[229] As a result, the city is a major transportation hub for the whole of south-eastern Europe,[230] carrying, among other things, trade to and from the neighbouring countries.[citation needed]

In recent years Thessaloniki has begun to turn into a major port for cruising in the eastern Mediterranean.[227] The Greek ministry of tourism considers Thessaloniki to be Greece's second most important commercial port,[231] and companies such as Royal Caribbean International have expressed interest in adding the Port of Thessaloniki to their destinations.[231] A total of 30 cruise ships are expected to arrive at Thessaloniki in 2011.[231]

After WWII and the Greek Civil War, heavy industrialization of the city's suburbs began in the mid-1950s.[232]

During the 1980s, a spate of factory shutdowns occurred, mostly of automobile manufacturers, such as Agricola, AutoDiana, EBIAM, Motoemil, Pantelemidis-TITAN and C.AR. Since the 1990s, companies took advantage of cheaper labour markets and more lax regulations than in other countries, and among the largest companies to shut down factories were Goodyear,[233] AVEZ pasta industry (one of the first industrial factories in northern Greece, built in 1926),[234] Philkeram Johnson, AGNO dairy and VIAMIL.

However, Thessaloniki still remains a major business hub in the Balkans and Greece, with a number of important Greek companies headquartered in the city, such as the Hellenic Vehicle Industry (ELVO), Namco, Astra Airlines, Ellinair, Pyramis and MLS Multimedia, which introduced the first Greek-built smartphone in 2012.[235]

In early 1960s, with the collaboration of Standard Oil and ESSO-Pappas, a large industrial zone was created, containing refineries, oil refinery and steel production (owned by Hellenic Steel Co.). The zone attracted also a series of different factories during the next decades.

Titan Cement has also facilities outside the city, on the road to Serres,[236] such as the AGET Heracles, a member of the Lafarge group, and Alumil SA.

Multinational companies such as Air Liquide, Cyanamid, Nestlé, Pfizer, Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company and Vivartia have also industrial facilities in the suburbs of the city.[237]

Foodstuff or drink companies headquartered in the city include the Macedonian Milk Industry (Mevgal), Allatini, Barbastathis, Hellenic Sugar Industry, Haitoglou Bros, Mythos Brewery, Malamatina, while the Goody's chain started from the city.[citation needed]

The American Farm School also is an important contributor to local food production.[238]

In 2011, the regional unit of Thessaloniki had a Gross Domestic Product of €18.293 billion (ranked second amongst the country's regional units),[220] comparable to Bahrain or Cyprus, and a per capita of €15,900 (ranked 16th).[220] In Purchasing Power Parity, the same indicators are €19,851 billion (2nd)[220] and €17,200 (15th) respectively.[220] In terms of comparison with the European Union average, Thessaloniki's GDP per capita indicator stands at 63% the EU average[220] and 69% in PPP[220] – this is comparable to the German state of Brandenburg.[220] Overall, Thessaloniki accounts for 8.9% of the total economy of Greece.[220] Between 1995 and 2008 Thessaloniki's GDP saw an average growth rate of 4.1% per annum (ranging from +14.5% in 1996 to −11.1% in 2005) while in 2011 the economy contracted by −7.8%.[220]

The tables below show the ethnic statistics of Thessaloniki during the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

The municipality of Thessaloniki is the most populous in the Thessaloniki Urban Area. Its population has increased in the latest census and the metropolitan area's population rose to over one million. The city forms the base of the Thessaloniki metropolitan area, with latest census in 2021 giving it a population of 1,091,424.[239]

The Jewish population in Greece is the oldest in mainland Europe (see Romaniotes). When Paul the Apostle came to Thessaloniki, he taught in the area of what today is called Upper City. Later, during the Ottoman period, with the coming of Sephardic Jews from Spain, the community of Thessaloniki became mostly Sephardic. Thessaloniki became the largest centre in Europe of the Sephardic Jews, who nicknamed the city la madre de Israel (Israel's mother)[147] and "Jerusalem of the Balkans".[244] It also included the historically significant and ancient Greek-speaking Romaniote community. During the Ottoman era, Thessaloniki's Sephardic community was half of the population according to the Ottoman Census of 1902 and almost 40% the city's population of 157,000 about 1913; Jewish merchants were prominent in commerce until the ethnic Greek population increased after Thessaloniki was incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece in 1913. By the 1680s, about 300 families of Sephardic Jews, followers of Sabbatai Zevi, had converted to Islam, becoming a sect known as the Dönmeh (convert), and migrated to Salonika, whose population was majority Jewish. They established an active community that thrived for about 250 years. Many of their descendants later became prominent in trade.[245] Many Jewish inhabitants of Thessaloniki spoke Judeo-Spanish, the Romance language of the Sephardic Jews.[246]

From the second half of the 19th century with the Ottoman reforms, the Jewish community had a new revival. Many French and especially Italian Jews (from Livorno and other cities), influential in introducing new methods of education and developing new schools and intellectual environments for the Jewish population, were established in Thessaloniki. Such modernists introduced also new techniques and ideas from the industrialised Western Europe and from the 1880s the city began to industrialize. The Italian-Jewish Allatini brothers led Jewish entrepreneurship, establishing milling and other food industries, brickmaking and processing plants for tobacco. Several traders supported the introduction of a large textile-production industry, superseding the weaving of cloth in a system of artisanal production. Notable names of the era include among others the Italo-Jewish Modiano family and the Allatini. Benrubis founded also in 1880 one of the first retail companies in the Balkans.

After the Balkan Wars, Thessaloniki was incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece in 1913. At first, the community feared that the annexation would lead to difficulties and during the first years its political stance was, in general, anti-Venizelist and pro-royalist/conservative. The Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 during World War I burned much of the centre of the city and left 50,000 Jews homeless of the total of 72,000 residents who were burned out.[137] Having lost homes and their businesses, many Jews emigrated to the United States, Palestine, and Paris. They could not wait for the government to create a new urban plan for rebuilding, which was eventually done.[247]

After the Greco-Turkish War in 1922 and the bilateral population exchange between Greece and Turkey, many refugees came to Greece. Nearly 100,000 ethnic Greeks resettled in Thessaloniki, reducing the proportion of Jews in the total community. After this, Jews made up about 20% of the city's population. During the interwar period, Greece granted Jewish citizens the same civil rights as other Greek citizens.[137] In March 1926, Greece re-emphasized that all citizens of Greece enjoyed equal rights, and a considerable proportion of the city's Jews decided to stay. During the Metaxas regime, the stance towards Jews improved even more.

World War II brought disaster for the Jewish Greeks, since in 1941 the Germans occupied Greece and began actions against the Jewish population. Greeks of the Resistance helped save some of the Jewish residents.[147] By the 1940s, the great majority of the Jewish Greek community firmly identified as both Greek and Jewish. According to Misha Glenny, such Greek Jews had largely not encountered "anti-Semitism as in its North European form."[248]

In 1943, the Nazis began brutal actions against the historic Jewish population in Thessaloniki, forcing them into a ghetto near the railroad lines and beginning deportation to concentration and labor camps. They deported and exterminated approximately 94% of Thessaloniki's Jews of all ages during the Holocaust.[249] The Thessaloniki Holocaust memorial in Eleftherias ("Freedom") Square was built in 1997 in memory of all the Jewish people from Thessaloniki murdered in the Holocaust. The site was chosen because it was the place where Jewish residents were rounded up before embarking on trains for concentration camps.[250][251] Today, a community of around 1,200 remains in the city.[147] Communities of descendants of Thessaloniki Jews – both Sephardic and Romaniote – live in other areas, mainly the United States and Israel.[249] Israeli singer Yehuda Poliker recorded a song about the Jewish people of Thessaloniki, called "Wait for me, Thessaloniki".

Since the late 19th century, many merchants from Western Europe (mainly from France and Italy) were established in the city. They had an important role in the social and economic life of the city and introduced new industrial techniques. Their main district was what is known today as the "Frankish district" (near Ladadika), where the Catholic church designed by Vitaliano Poselli is also situated.[253][254] A part of them left after the incorporation of the city into the Greek kingdom, while others, who were of Jewish faith, were exterminated by the Nazis.

The Bulgarian community of the city increased during the late 19th century.[255] The community had a Men's High School, a Girl's High School, a trade union and a gymnastics society. A large part of them were Catholics, as a result of actions by the Lazarists society, which had its base in the city.

Another group is the Armenian community which dates back to the Byzantine and Ottoman periods. During the 20th century, after the Armenian genocide and the defeat of the Greek army in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22), many fled to Greece including Thessaloniki. There is also an Armenian cemetery and an Armenian church at the centre of the city.[256]

Thessaloniki is regarded not only as the cultural and entertainment capital of northern Greece[213][257] but also the cultural capital of the country as a whole.[12] The city's main theaters, run by the National Theatre of Northern Greece (Greek: Κρατικό Θέατρο Βορείου Ελλάδος) which was established in 1961,[258] include the Theater of the Society of Macedonian Studies, where the National Theater is based, the Royal Theater (Βασιλικό Θέατρο) - the first base of the National Theater - Moni Lazariston, and the Earth Theater and Forest Theater, both amphitheatrical open-air theatres overlooking the city.[258]

The title of the European Capital of Culture in 1997 saw the birth of the city's first opera[259] and today forms an independent section of the National Theatre of Northern Greece.[260] The opera is based at the Thessaloniki Concert Hall, one of the largest concert halls in Greece. Recently a second building was also constructed and designed by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki. Thessaloniki is also the seat of two symphony orchestras, the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra and the Symphony Orchestra of the Municipality of Thessaloniki.Olympion Theater, the site of the Thessaloniki International Film Festival and the Plateia Assos Odeon multiplex are the two major cinemas in downtown Thessaloniki. The city also has a number of multiplex cinemas in major shopping malls in the suburbs, most notably in Mediterranean Cosmos, the largest retail and entertainment development in the Balkans.

Thessaloniki is renowned for its major shopping streets and lively laneways. Tsimiski Street, Mitropoleos and Proxenou Koromila avenue are the city's most famous shopping streets and are among Greece's most expensive and exclusive high streets. The city is also home to one of Greece's most famous and prestigious hotels, Makedonia Palace hotel, the Hyatt Regency Casino and hotel (the biggest casino in Greece and one of the biggest in Europe) and Waterland, the largest water park in southeastern Europe.

The city has long been known in Greece for its vibrant city culture, including having the most cafes and bars per capita of any city in Europe; and as having some of the best nightlife and entertainment in the country, thanks to its large young population and multicultural feel. Lonely Planet listed Thessaloniki among the world's "ultimate party cities".[261]

Although Thessaloniki is not renowned for its parks and greenery throughout its urban area, where green spaces are few, it has several large open spaces around its waterfront, namely the central city gardens of Palios Zoologikos Kipos (which is recently being redeveloped to also include rock climbing facilities, a new skatepark and paintball range),[262] the park of Pedion tou Areos, which also holds the city's annual floral expo; and the parks of the Nea Paralia (waterfront) that span for 3 km (2 mi) along the coast, from the White Tower to the concert hall.

The Nea Paralia parks are used throughout the year for a variety of events, while they open up to the Thessaloniki waterfront, which is lined up with several cafés and bars; and during summer is full of Thessalonians enjoying their long evening walks (referred to as "the volta" and is embedded into the culture of the city). Having undergone an extensive revitalization, the city's waterfront today features a total of 12 thematic gardens/parks.[263]

Thessaloniki's proximity to places such as the national parks of Pieria and beaches of Chalkidiki often allow its residents to easily have access to some of the best outdoor recreation in Europe; however, the city is also right next to the Seich Sou forest national park, just 3.5 km (2 mi) away from Thessaloniki's city centre; and offers residents and visitors alike, quiet viewpoints towards the city, mountain bike trails and landscaped hiking paths.[264] The city's zoo, which is operated by the municipality of Thessaloniki, is also located nearby the national park.[265]

Other recreation spaces throughout the Thessaloniki metropolitan area include the Fragma Thermis, a landscaped parkland near Thermi and the Delta wetlands west of the city centre; while urban beaches that have continuously been awarded the blue flags,[266] are located along the 10 km (6 mi) coastline of Thessaloniki's southeastern suburbs of Thermaikos, about 20 km (12 mi) away from the city centre.

Because of the city's rich and diverse history, Thessaloniki houses many museums dealing with many different eras in history. Two of the city's most famous museums include the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of Byzantine Culture.

The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki was established in 1962 and houses some of the most important ancient Macedonian artifacts,[267] including an extensive collection of golden artwork from the royal palaces of Aigai and Pella.[268] It also houses exhibits from Macedon's prehistoric past, dating from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age.[269] The Prehistoric Antiquities Museum of Thessaloniki has exhibits from those periods as well.

The Museum of Byzantine Culture is one of the city's most famous museums, showcasing the city's glorious Byzantine past.[270] The museum was also awarded Council of Europe's museum prize in 2005.[271] The museum of the White Tower of Thessaloniki houses a series of galleries relating to the city's past, from the creation of the White Tower until recent years.[272]

One of the most modern museums in the city is the Thessaloniki Science Centre and Technology Museum and is one of the most high-tech museums in Greece and southeastern Europe.[273] It features the largest planetarium in Greece, a cosmotheatre with the country's largest flat screen, an amphitheater, a motion simulator with 3D projection and 6-axis movement and exhibition spaces.[273] Other industrial and technological museums in the city include the Railway Museum of Thessaloniki, which houses an original Orient Express train, the War Museum of Thessaloniki and others. The city also has a number of educational and sports museums, including the Thessaloniki History Centre and the Thessaloniki Olympic Museum.

The Atatürk Museum in Thessaloniki is the historic house where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern-day Turkey, was born. The house is now part of the Turkish consulate complex, but admission to the museum is free.[274] The museum contains historic information about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his life, especially while he was in Thessaloniki.[274] Other ethnological museums of the sort include the Historical Museum of the Balkan Wars, the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, containing information about the anti-Ottoman rebellions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[275] Construction on the Holocaust Museum of Greece began in the city in 2018.[203]

The city also has a number of important art galleries. Such include the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, housing exhibitions from a number of well-known Greek and foreign artists.[276] The Teloglion Foundation of Art is part of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and includes an extensive collection of works by important artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, including works by prominent Greeks and native Thessalonians.[277] The Thessaloniki Museum of Photography also houses a number of important exhibitions, and is located within the old port of Thessaloniki.[278]

Thessaloniki is home to a number of prominent archaeological sites. Apart from its recognized UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Thessaloniki features a large two-terraced Roman forum[279] featuring two-storey stoas,[280] dug up by accident in the 1960s.[279] The forum complex also boasts two Roman baths,[281] one of which has been excavated while the other is buried underneath the city.[281] The forum also features a small theater,[279][281] which was also used for gladiatorial games.[280] Although the initial complex was not built in Roman times, it was largely refurbished in the second century.[281] It is believed that the forum and the theater continued to be used until at least the sixth century.[282]

Another important archaeological site is the imperial palace complex which Roman emperor Galerius, located at Navarinou Square, commissioned when he made Thessaloniki the capital of his portion of the Roman Empire.[44][45] The large octagonal portion of the complex, most of which survives to this day, is believed to have been an imperial throne room.[280] Various mosaics from the palatial complex have also survived.[283] Some historians believe that the complex must have been in use as an imperial residence until the 11th century.[282]

Not far from the palace itself is the Arch of Galerius,[283] known colloquially as the Kamara. The arch was built to commemorate the emperor's campaigns against the Persians.[280][283] The original structure featured three arches;[280] however, only two full arches and part of the third survive to this day. Many of the arches' marble parts survive as well,[280] although it is mostly the brick interior that can be seen today.

Other monuments of the city's past, such as Las Incantadas, a Caryatid portico from the ancient forum, have been removed or destroyed over the years. Las Incantadas in particular are on display at the Louvre.[279][284] Thanks to a private donation of €180,000, it was announced on 6 December 2011 that a replica of Las Incantadas would be commissioned and later put on display in Thessaloniki.[284]

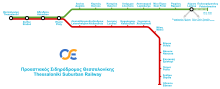

The construction of the Thessaloniki Metro inadvertently started the largest archaeological dig not only of the city, but of Northern Greece; the dig spans 20 km2 (7.7 sq mi) and has unearthed 300,000 individual artefacts from as early as the Roman Empire and as late as the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917.[285][286] Ancient Thessaloniki's Decumanus Maximus was also found and 75 metres (246 ft) of the marble-paved and column-lined road were unearthed along with shops, other buildings, and plumbing, prompting one scholar to describe the discovery as "the Byzantine Pompeii".[287] Some of the artefacts will be put on display inside the metro stations, while Venizelou will feature the world's first open archaeological site located within a metro station.[288][289]

Thessaloniki is home of a number of festivals and events.[290] The Thessaloniki International Fair is the most important event to be hosted in the city annually, by means of economic development. It was first established in 1926[291] and takes place every year at the 180,000 m2 (1,900,000 sq ft) Thessaloniki International Exhibition Centre. The event attracts major political attention and it is customary for the Prime Minister of Greece to outline his administration's policies for the next year during the event. Over 250,000 visitors attended the exposition in 2010.[292] The new Art Thessaloniki, is starting first time 29.10. – 1 November 2015 as an international contemporary art fair. The Thessaloniki International Film Festival is established as one of the most important film festivals in Southern Europe,[293] with a number of notable filmmakers such as Francis Ford Coppola, Faye Dunaway, Catherine Deneuve, Irene Papas and Fatih Akın taking part, and was established in 1960.[294] The Documentary Festival, founded in 1999, has focused on documentaries that explore global social and cultural developments, with many of the films presented being candidates for FIPRESCI and Audience Awards.[295]

The Dimitria festival, founded in 1966 and named after the city's patron saint of St. Demetrius, has focused on a wide range of events including music, theatre, dance, local happenings, and exhibitions.[296] The DMC DJ Championship has been hosted at the International Trade Fair of Thessaloniki, has become a worldwide event for aspiring DJs and turntablists. The International Festival of Photography has taken place every February to mid-April.[297] Exhibitions for the event are sited in museums, heritage landmarks, galleries, bookshops and cafés. Thessaloniki also holds an annual International Book Fair.[298]

Between 1962–1997 and 2005–2008, the city also hosted the Thessaloniki Song Festival,[299] Greece's most important music festival, at Alexandreio Melathron.[300]

In 2012, the city hosted its first pride parade, Thessaloniki Pride, which took place between 22 and 23 June.[301] It has been held every year ever since, however in 2013 transgender people participating in the parade became victims of police brutality. The issue was soon settled by the government.[302] The city's Greek Orthodox Church leadership has consistently rallied against the event, but mayor Boutaris sided with Thessaloniki Pride, saying also that Thessaloniki would seek to host EuroPride 2020.[303] The event was given to Thessaloniki in September 2017, beating Bergen, Brussels, and Hamburg.[304]Since 1998, the city host Thessaloniki International G.L.A.D. Film Festival, the first LGBT film festival in Greece.

The main stadium of the city is the Kaftanzoglio Stadium (also home ground of Iraklis F.C.), while other main stadiums of the city include the football Toumba Stadium and Kleanthis Vikelidis Stadium home grounds of PAOK FC and Aris F.C., respectively, all of whom are founding members of the Greek league.

Being the largest "multi-sport" stadium in the city, Kaftanzoglio Stadium regularly plays host to athletics events; such as the European Athletics Association event "Olympic Meeting Thessaloniki" every year; it has hosted the Greek national championships in 2009 and has been used for athletics at the Mediterranean Games and for the European Cup in athletics. In 2004, the stadium served as an official Athens 2004 venue,[305] while in 2009 the city and the stadium hosted the 2009 IAAF World Athletics Final.

Thessaloniki's major indoor arenas include the state-owned Alexandreio Melathron, P.A.O.K. Sports Arena and the YMCA indoor hall. Other sporting clubs in the city include Apollon FC based in Kalamaria, Agrotikos Asteras F.C. based in Evosmos and YMCA. Thessaloniki has a rich sporting history with its teams winning the first ever panhellenic football (Aris FC),[306] basketball (Iraklis BC),[307] and water polo (AC Aris)[308] tournaments.

During recent years, PAOK FC has emerged as the strongest football club of the city, winning also the Greek championship without a defeat (2018–19 season).

The city played a major role in the development of basketball in Greece. The local YMCA was the first to introduce the sport to the country, while Iraklis B.C. won the first ever Greek championship.[307] From 1982 to 1993 Aris B.C. dominated the league, regularly finishing in first place. In that period Aris won a total of 9 championships, 7 cups and one European Cup Winners' Cup. The city also hosted the 2003 FIBA Under-19 World Championship in which Greece came third. In volleyball, Iraklis has emerged since 2000 as one of the most successful teams in Greece[309] and Europe – see 2005–06 CEV Champions League.[310] In October 2007, Thessaloniki also played host to the first Southeastern European Games.[311]

The city is also the finish point of the annual Alexander The Great Marathon, which starts at Pella, in recognition of its Ancient Macedonian heritage.[312]There are also aquatic and athletic complexes such as Ethniko and Poseidonio.

Thessaloniki is home to the ERT3 TV-channel and Radio Macedonia, both services of Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation (ERT) operating in the city and are broadcast all over Greece.[313]The municipality of Thessaloniki also operates three radio stations, namely FM100, FM101 and FM100.6;[citation needed] and TV100, a television network which was also the first non-state-owned TV station in Greece and opened in 1988.[citation needed] Several private TV-networks also broadcast out from Thessaloniki, with Makedonia TV being the most popular.

The city's main newspapers and some of the most circulated in Greece, include Makedonia, which was also the first newspaper published in Thessaloniki in 1911 and Aggelioforos. A large number of radio stations also broadcast from Thessaloniki as the city is known for its music contributions.

Throughout its history, Thessaloniki has been home to a number of well-known figures and people.

.jpg/440px-Frappe_(4547117210).jpg)