Священная Римская империя [ f] также известная как Священная Римская империя германской нации после 1512 года, была политическим образованием в Центральной и Западной Европе , обычно возглавляемым императором Священной Римской империи . [19] Она возникла в раннем Средневековье и просуществовала почти тысячу лет до своего распада в 1806 году во время наполеоновских войн . [20]

25 декабря 800 года папа Лев III короновал франкского короля Карла Великого как римского императора, возродив этот титул в Западной Европе более чем через три столетия после падения древней Западной Римской империи в 476 году. [21] Титул утратил силу в 924 году, но был возрожден в 962 году, когда Оттон I был коронован императором папой Иоанном XII , объявив себя преемником Карла Великого и Каролингской империи , [22] и положив начало непрерывному существованию империи на протяжении более восьми столетий. [23] [24] [g] С 962 года по XII век империя была одной из самых могущественных монархий в Европе. [25] Функционирование правительства зависело от гармоничного сотрудничества между императором и вассалами; [26] эта гармония была нарушена в период Салических королей . [27] Империя достигла пика территориальной экспансии и могущества при династии Гогенштауфенов в середине XIII века, но чрезмерное расширение ее власти привело к частичному краху. [28] [29]

Ученые обычно описывают эволюцию институтов и принципов, составляющих империю, и постепенное развитие императорской роли. [30] [31] Хотя должность императора была восстановлена, точный термин для его королевства как «Священная Римская империя» не использовался до 13-го века, [32] хотя теоретическая легитимность императора с самого начала основывалась на концепции translatio imperii , что он обладал верховной властью, унаследованной от древних императоров Рима . [30] Тем не менее, в Священной Римской империи императорская должность традиционно была выборной, в основном, немецкими курфюрстами . В теории и дипломатии императоры считались первыми среди равных всех католических монархов Европы. [33]

Процесс имперской реформы в конце 15-го и начале 16-го веков преобразовал империю, создав ряд институтов, которые просуществовали до ее окончательного упадка в 19-м веке. [34] [35] По словам историка Томаса Брэди-младшего, империя после имперской реформы была политическим образованием, отличавшимся замечательной долговечностью и стабильностью, и «в некоторых отношениях напоминала монархические политии западного яруса Европы, а в других — слабо интегрированные выборные политии Восточной Центральной Европы». Новая корпоративная немецкая нация, вместо того чтобы просто подчиняться императору, вела с ним переговоры. [36] [37] 6 августа 1806 года император Франц II отрекся от престола и официально распустил империю после создания — месяцем ранее французским императором Наполеоном — Рейнского союза , конфедерации немецких государств-клиентов, лояльных не императору Священной Римской империи, а Франции.

Со времен Карла Великого королевство именовалось просто Римской империей . [38] Термин sacrum («священный», в смысле «освященный») в связи со средневековой Римской империей использовался, начиная с 1157 года при Фридрихе I Барбароссе («Священная империя»): термин был добавлен, чтобы отразить амбиции Фридриха доминировать в Италии и папстве . [39] Форма «Священная Римская империя» засвидетельствована с 1254 года. [40]

Точный термин «Священная Римская империя» не использовался до XIII века, до этого империя именовалась по-разному: universum regnum («все королевство», в отличие от региональных королевств), imperium christianum («Христианская империя») или Romanum imperium («Римская империя»), [32] но легитимность императора всегда основывалась на концепции translatio imperii , [h] что он обладал верховной властью, унаследованной от древних императоров Рима . [30]

В указе, последовавшем за Кельнским сеймом в 1512 году, название было изменено на Священную Римскую империю германской нации ( ‹См. Tfd› нем .: Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation , лат .: Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Germanicae ), [38] форма, впервые использованная в документе в 1474 году. [39] Принятие этого нового названия совпало с потерей имперских территорий в Италии и Бургундии на юге и западе к концу 15 века, [41] но также для того, чтобы подчеркнуть новую важность немецких императорских сословий в управлении империей из-за имперской реформы . [42] Венгерское наименование «Германская Римская империя» ( венг .: Német-római Birodalom ) является сокращением этого. [43]

К концу XVIII века термин «Священная Римская империя германской нации» вышел из официального употребления. Вопреки традиционному взгляду на это обозначение, Герман Вайзерт в исследовании имперской титулатуры утверждал, что, несмотря на утверждения многих учебников, название «Священная Римская империя германской нации» никогда не имело официального статуса, и указывает, что в документах в тридцать раз чаще опускался национальный суффикс, чем включался. [44]

В известной оценке этого названия политический философ Вольтер сардонически заметил: «Это образование, которое называлось и которое до сих пор называет себя Священной Римской империей, никоим образом не было ни святым, ни римским, ни империей». [45]

В современный период Империя часто неофициально называлась Германской империей ( Deutsches Reich ) или Римско-германской империей ( Römisch-Deutsches Reich ). [46] После распада и до конца Германской империи ее часто называли «старой империей» ( das alte Reich ). Начиная с 1923 года немецкие националисты начала двадцатого века и пропаганда нацистской партии идентифицировали Священную Римскую империю как «Первый» Рейх ( Erstes Reich , Reich означает империя), Германскую империю как «Второй» Рейх, а то, что в конечном итоге стало нацистской Германией, как «Третий» Рейх. [47]

Дэвид С. Бахрах полагает, что короли Оттонов на самом деле построили свою империю на основе военных и бюрократических аппаратов, а также культурного наследия, которое они унаследовали от Каролингов, которые в конечном итоге унаследовали это от Поздней Римской империи. Он утверждает, что империя Оттонов вряд ли была архаичным королевством примитивных германцев, поддерживаемым только личными отношениями и движимым желанием магнатов грабить и делить награды между собой, но вместо этого примечательным своими способностями накапливать сложные экономические, административные, образовательные и культурные ресурсы, которые они использовали для обслуживания своей огромной военной машины. [48] [49]

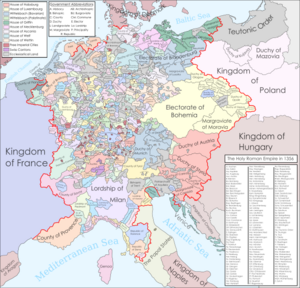

До конца XV века империя теоретически состояла из трех основных блоков — Италии , Германии и Бургундии . Позже территориально остались только Королевство Германии и Богемия, а бургундские территории были утеряны Францией . Хотя итальянские территории формально входили в состав империи, в ходе Имперской реформы они были проигнорированы и расколоты на многочисленные фактически независимые территориальные образования. [50] [30] [37] Статус Италии, в частности, менялся на протяжении XVI-XVIII веков. Некоторые территории, такие как Пьемонт-Савойя, становились все более независимыми, в то время как другие становились все более зависимыми из-за исчезновения их правящих дворянских домов, в результате чего эти территории часто попадали под власть Габсбургов и их младших ветвей . За исключением потери Франш-Конте в 1678 году , внешние границы Империи не претерпели заметных изменений с Вестфальского мира , который признал исключение Швейцарии и Северных Нидерландов, а также французский протекторат над Эльзасом, до распада Империи. По завершении Наполеоновских войн в 1815 году большая часть Священной Римской империи была включена в Германский союз , за исключением итальянских государств.

Поскольку римская власть в Галлии пришла в упадок в V веке, местные германские племена взяли под свой контроль [51] . В конце V и начале VI веков Меровинги под предводительством Хлодвига I и его преемников объединили франкские племена и распространили гегемонию на другие, чтобы получить контроль над северной Галлией и регионом долины реки Средний Рейн . [52] [53] К середине VIII века Меровинги были низведены до номинальных лидеров, а Каролинги во главе с Карлом Мартеллом стали фактическими правителями [54] . В 751 году сын Мартелла Пипин стал королем франков, а позже получил одобрение Папы. [55] [56] Каролинги поддерживали тесный союз с папством. [57]

В 768 году сын Пипина Карл Великий стал королем франков и начал обширное расширение королевства. В конечном итоге он включил в себя территории современной Франции, Германии, северной Италии, Нидерландов и далее, связав Франкское королевство с папскими землями. [58] [59]

Хотя антагонизм по поводу расходов на византийское господство долго сохранялся в Италии, политический разрыв был серьезно вызван в 726 году иконоборчеством императора Льва III Исавра , в котором папа Григорий II видел последнюю в серии императорских ересей. [60] В 797 году император Восточной Римской империи Константин VI был отстранен от престола своей матерью, императрицей Ириной , которая объявила себя единоличной правительницей. Поскольку Латинская Церковь считала только римского императора-мужчину главой христианского мира , папа Лев III искал нового кандидата на этот сан, исключив консультации с патриархом Константинопольским . [61] [62]

Хорошая служба Карла Великого Церкви в защите папских владений от лангобардов сделала его идеальным кандидатом. На Рождество 800 года Папа Лев III короновал Карла Великого императором, восстановив титул на Западе впервые за более чем три столетия. [61] [62] Это можно рассматривать как символ отхода папства от приходящей в упадок Византийской империи в сторону новой власти Каролингской Франкии . Карл Великий принял формулу Renovatio imperii Romanorum («возрождение Римской империи»). В 802 году Ирина была свергнута и сослана Никифором I , и с тех пор было два римских императора.

После смерти Карла Великого в 814 году императорская корона перешла к его сыну Людовику Благочестивому . После смерти Людовика в 840 году она перешла к его сыну Лотарю , который был его соправителем. К этому моменту территория Карла Великого была разделена на несколько территорий ( ср . Верденский договор , Прюмский договор , Мерсенский договор и Рибемонский договор ), и в течение более позднего IX века титул императора оспаривался Каролингскими правителями Западно-Франкского королевства или Западно-Франкского королевства и Восточно-Франкского королевства или Восточно-Франкского королевства , сначала западным королем ( Карлом Лысым ), а затем восточным ( Карлом Толстым ), который ненадолго воссоединил Империю, получив приз. [63] В IX веке Карл Великий и его преемники способствовали интеллектуальному возрождению, известному как Каролингское Возрождение . Некоторые, как Мортимер Чемберс, [64] полагают, что Каролингское Возрождение сделало возможным последующие Ренессансы (хотя к началу X века возрождение уже пошло на убыль). [65]

После смерти Карла Толстого в 888 году Каролингская империя распалась и больше не восстанавливалась. Согласно Регино Прюмскому , части королевства «извергали королей», и каждая часть выбирала королей «из своих собственных недр». [63] Последним таким императором был Беренгар I Итальянский , который умер в 924 году.

Около 900 года автономные герцогства Восточной Франкии ( Франкония , Бавария , Швабия , Саксония и Лотарингия ) вновь появились. После того, как король Каролингов Людовик Дитя умер без потомства в 911 году, Восточная Франкия не обратилась к правителю Каролингов Западной Франкии, чтобы взять на себя управление королевством, а вместо этого избрала одного из герцогов, Конрада Франконского , в качестве Rex Francorum Orientalium . [66] На смертном одре Конрад уступил корону своему главному сопернику, Генриху Птицелову Саксонскому ( правил в 919–936 годах ), который был избран королем на сейме во Фрицларе в 919 году. [67] Генрих заключил перемирие с набегами мадьяр , и в 933 году одержал первую победу над ними в битве при Риаде . [68]

Генрих умер в 936 году, но его потомки, династия Людольфингов (или Оттонов) , продолжали править Восточным королевством или Королевством Германии примерно столетие. После смерти Генриха Птицелова, Отто , его сын и назначенный преемник, [69] был избран королем в Аахене в 936 году. [70] Он преодолел серию восстаний младшего брата и нескольких герцогов. После этого король сумел контролировать назначение герцогов и часто также использовал епископов в административных делах. [71] Он заменил лидеров большинства крупных восточно-франкских герцогств своими собственными родственниками. В то же время он был осторожен, чтобы не допустить, чтобы члены его собственной семьи посягали на его королевские прерогативы. [72] [73]

В 951 году Оттон пришел на помощь королеве Италии Аделаиде , победил ее врагов, женился на ней и взял под свой контроль Италию. [74] В 955 году Оттон одержал решительную победу над мадьярами в битве при Лехфельде . [75] В 962 году Оттон был коронован императором папой Иоанном XII , [75] таким образом переплетая дела Германского королевства с делами Италии и папства. Коронация Оттона в качестве императора обозначила немецких королей как преемников империи Карла Великого, что через концепцию translatio imperii также заставило их считать себя преемниками Древнего Рима. Расцвет искусств, начавшийся с правления Оттона Великого, известен как Оттоновское Возрождение , сосредоточенное в Германии, но также происходившее в Северной Италии и Франции. [76] [77]

Оттон создал имперскую церковную систему, часто называемую «Оттоновской церковной системой Рейха», которая связала великие имперские церкви и их представителей с имперской службой, тем самым обеспечив «стабильную и долгосрочную основу для Германии». [78] [79] В Оттоновскую эпоху императорские женщины играли видную роль в политических и церковных делах, часто совмещая свои функции религиозного лидера и советника, регента или соправителя, в частности Матильда Рингельхаймская , Эдгит , Аделаида Итальянская , Феофано и Матильда Кведлинбургская . [80] [81] [82] [83]

В 963 году Оттон низложил Иоанна XII и выбрал Льва VIII новым папой (хотя Иоанн XII и Лев VIII оба претендовали на папство до 964 года, когда Иоанн XII умер). Это также возобновило конфликт с византийским императором, особенно после того, как сын Оттона Оттон II ( правил в 967–983 годах ) принял титул imperator Romanorum . Тем не менее, Оттон II сформировал брачные связи с востоком, когда женился на византийской принцессе Феофану . [84] Их сын, Оттон III , взошел на престол всего в три года и подвергся борьбе за власть и серии регентств до своего совершеннолетия в 994 году. До этого времени он оставался в Германии, в то время как свергнутый герцог Кресценций II правил Римом и частью Италии, якобы вместо него.

В 996 году Оттон III назначил своего кузена Григория V первым немецким папой. [85] Римская знать с подозрением относилась к иностранному папе и иностранным папским офицерам, которых подтолкнул к восстанию Кресценций II . Бывший наставник Оттона III антипапа Иоанн XVI недолгое время удерживал Рим, пока император Священной Римской империи не захватил город. [86]

Оттон умер молодым в 1002 году, и ему наследовал его двоюродный брат Генрих II , который сосредоточился на Германии. [87] Дипломатическая деятельность Оттона III (и его наставника папы Сильвестра) совпала с христианизацией и распространением латинской культуры в разных частях Европы и способствовала этому. [88] [89] Они вовлекли новую группу наций (славянских) в структуру Европы, а их империя функционировала, как некоторые замечают, как «президентство византийского типа над семьей наций, сосредоточенное вокруг папы и императора в Риме». Это оказалось долгосрочным достижением. [90] [91] [92] [93] Ранняя смерть Оттона, однако, сделала его правление «историей о в значительной степени нереализованном потенциале». [94] [95]

Генрих II умер в 1024 году, и Конрад II , первый из Салической династии , был избран королем только после некоторых дебатов среди герцогов и дворян. Эта группа в конечном итоге превратилась в коллегию выборщиков .

В конечном итоге Священная Римская империя состояла из четырех королевств:

Короли часто использовали епископов в административных делах и часто определяли, кто будет назначен на церковные должности. [96] После Клюнийских реформ такое участие все больше рассматривалось папством как неуместное. Реформаторски настроенный папа Григорий VII был полон решимости противостоять такой практике, что привело к спору об инвеституре с королем Генрихом IV ( правил в 1056–1106 , коронован императором в 1084 году). [96]

Генрих IV отверг вмешательство папы и убедил своих епископов отлучить папу, к которому он, как известно, обращался по его имени при рождении «Гильдебранд», а не по его папскому имени «Григорий». [97] Папа, в свою очередь, отлучил короля, объявил его низложенным и расторг клятвы верности, данные Генриху. [23] [97] Король оказался практически без политической поддержки и был вынужден совершить знаменитый поход в Каноссу в 1077 году, [98] с помощью которого он добился снятия отлучения ценой унижения. Тем временем немецкие князья избрали другого короля, Рудольфа Швабского . [99]

Генриху удалось победить Рудольфа, но впоследствии он столкнулся с новыми восстаниями, повторным отлучением и даже восстанием своих сыновей. После его смерти его второй сын, Генрих V , достиг соглашения с Папой и епископами в Вормсском конкордате 1122 года . [100] Политическая власть Империи была сохранена, но конфликт продемонстрировал пределы власти правителя, особенно в отношении Церкви, и лишил короля сакрального статуса, которым он ранее пользовался. Папа и немецкие князья появились как основные игроки в политической системе Священной Римской империи.

В результате Ostsiedlung менее населенные регионы Центральной Европы (т. е. малонаселенные приграничные районы в современных Польше и Чехии) получили значительное количество немецкоговорящих. Силезия стала частью Священной Римской империи в результате стремления местных герцогов Пястов к автономии от Польской короны. [101] С конца XII века герцогство Померания находилось под сюзеренитетом Священной Римской империи [102] , а завоевания Тевтонского ордена сделали этот регион немецкоговорящим. [103]

,_f.280v_-_BL_Royal_MS_15_E_I.jpg/440px-Crusaders_besieging_Damascus_-_Chronique_d'Ernoul_et_de_Bernard_le_Trésorier_(late_15th_C),_f.280v_-_BL_Royal_MS_15_E_I.jpg)

Когда династия Салиан закончилась со смертью Генриха V в 1125 году, князья решили не выбирать ближайшего родственника, а вместо него выбрать Лотаря III , умеренно могущественного, но уже старого герцога Саксонии. Когда он умер в 1137 году, князья снова решили ограничить королевскую власть; соответственно, они не выбрали любимого наследника Лотаря, его зятя Генриха Гордого из семьи Вельфов , а Конрада III из семьи Гогенштауфенов , внука императора Генриха IV и племянника императора Генриха V. Это привело к более чем столетнему раздору между двумя домами. Конрад изгнал Вельфов из их владений, но после его смерти в 1152 году его племянник Фридрих Барбаросса стал его преемником и заключил мир с Вельфами, вернув своему кузену Генриху Льву его – хотя и уменьшенные – владения.

Правители Гогенштауфенов все чаще сдавали землю в аренду « министериалам », бывшим несвободным военнослужащим, которые, как надеялся Фридрих, были более надежными, чем герцоги. Первоначально использовавшийся в основном для военных служб, этот новый класс людей стал основой для последующих рыцарей , еще одной основы имперской власти. Еще одним важным конституционным шагом в Ронкалье стало создание нового механизма мира для всей империи, Landfrieden , первый из которых был выпущен в 1103 году при Генрихе IV в Майнце . [104] [105]

Это была попытка отменить частную вражду между многочисленными герцогами и другими людьми и привязать подчиненных императора к правовой системе юрисдикции и публичного преследования за уголовные деяния — предшественник современной концепции « верховенства закона ». Другой новой концепцией того времени было систематическое основание новых городов императором и местными герцогами. Это было отчасти результатом взрыва населения; они также концентрировали экономическую власть в стратегических местах. До этого города существовали только в форме старых римских оснований или старых епископств . Города, которые были основаны в 12 веке, включают Фрайбург , возможно, экономическую модель для многих более поздних городов, и Мюнхен .

Фридрих Барбаросса был коронован императором в 1155 году. Он подчеркивал «римскость» империи, отчасти в попытке оправдать власть императора, независимую от (теперь усиленного) папы. Императорское собрание на полях Ронкальи в 1158 году восстановило императорские права со ссылкой на Corpus Juris Civilis Юстиниана I. Императорские права назывались регалиями со времен споров об инвеституре, но были впервые перечислены в Ронкалье. Этот полный список включал общественные дороги, тарифы, чеканку монет , сбор штрафных пошлин, а также назначение и смещение должностных лиц. Эти права теперь были явно укоренены в римском праве , далеко идущем конституционном акте.

Политика Фридриха была в первую очередь направлена на Италию, где он столкнулся с свободомыслящими городами севера, особенно с герцогством Миланским . Он также ввязался в другой конфликт с папством, поддержав кандидата, избранного меньшинством против папы Александра III (1159–1181). Фридрих поддерживал череду антипап , прежде чем окончательно заключить мир с Александром в 1177 году. В Германии император неоднократно защищал Генриха Льва от жалоб со стороны соперничающих князей или городов (особенно в случаях Мюнхена и Любека ). Генрих оказывал лишь слабую поддержку политике Фридриха, и в критической ситуации во время итальянских войн Генрих отклонил просьбу императора о военной поддержке. Вернувшись в Германию, озлобленный Фридрих начал судебное разбирательство против герцога, что привело к публичному запрету и конфискации всех территорий Генриха. В 1190 году Фридрих принял участие в Третьем крестовом походе и умер в Армянском королевстве Киликия . [106]

В период Гогенштауфенов немецкие князья способствовали успешному мирному заселению на востоке земель, которые были необитаемы или мало заселены западными славянами . Немецкоязычные фермеры, торговцы и ремесленники из западной части империи, как христиане, так и евреи, переселились в эти районы. Постепенная германизация этих земель была сложным явлением, которое не следует интерпретировать в предвзятых терминах национализма 19-го века . Заселение на восток расширило влияние империи, включив Померанию и Силезию , как и смешанные браки местных, все еще в основном славянских, правителей с немецкими супругами. Тевтонские рыцари были приглашены в Пруссию герцогом Конрадом Мазовецким для христианизации пруссов в 1226 году. Монашеское государство Тевтонского ордена ( ‹См. Tfd› на немецком языке : Deutschordensstaat ) и его более позднее немецкое государство-преемник герцогство Пруссия никогда не были частью Священной Римской империи.

При сыне и преемнике Фридриха Барбароссы, Генрихе VI , династия Гогенштауфенов достигла своего расцвета с присоединением нормандского королевства Сицилия через брак Генриха VI и Констанции Сицилийской . Богемия и Польша находились под феодальной зависимостью, в то время как Кипр и Малая Армения также платили дань. Иберо-марокканский халиф принял его претензии на сюзеренитет над Тунисом и Триполитанией и заплатил дань. Опасаясь власти Генриха, самого могущественного монарха в Европе со времен Карла Великого, другие европейские короли заключили союз. Но Генрих разрушил эту коалицию, шантажируя английского короля Ричарда Львиное Сердце . Византийский император беспокоился, что Генрих обратит свой план крестового похода против его империи, и начал собирать алеманикон , чтобы подготовиться к ожидаемому вторжению. У Генриха также были планы превратить империю в наследственную монархию, хотя это встретило сопротивление со стороны некоторых принцев и папы. Император внезапно умер в 1197 году, что привело к частичному краху его империи. [107] [108] [109] Поскольку его сын Фридрих II , хотя и был уже избран королем, был еще маленьким ребенком и жил на Сицилии, немецкие князья решили избрать взрослого короля, что привело к двойным выборам младшего сына Фридриха Барбароссы Филиппа Швабского и сына Генриха Льва Отто Брауншвейгского , которые соревновались за корону. После того, как Филипп был убит в частной ссоре в 1208 году, Отто некоторое время преобладал, пока не начал претендовать также на Сицилию. [ необходимо разъяснение ]

Папа Иннокентий III , опасавшийся угрозы, которую представлял союз империи и Сицилии, теперь поддерживался Фридрихом II, который двинулся в Германию и победил Оттона. После своей победы Фридрих не выполнил своего обещания сохранить два королевства раздельными. Хотя он сделал своего сына Генриха королем Сицилии перед походом на Германию, он все еще сохранял за собой реальную политическую власть. Это продолжалось и после того, как Фридрих был коронован императором в 1220 году. Опасаясь концентрации власти Фридрихом, папа в конце концов отлучил его от церкви. Еще одним предметом разногласий был Крестовый поход, который Фридрих обещал, но неоднократно откладывал. Теперь, хотя и отлученный, Фридрих возглавил Шестой крестовый поход в 1228 году, который закончился переговорами и временным восстановлением Иерусалимского королевства .

Несмотря на его имперские претензии, правление Фридриха стало важным поворотным моментом к распаду центральной власти в Империи. Сосредоточившись на создании более централизованного государства в Сицилии, он в основном отсутствовал в Германии и выдал далеко идущие привилегии светским и церковным князьям Германии: в 1220 году Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis Фридрих отказался от ряда регалий в пользу епископов, среди которых были тарифы, чеканка монет и право строить укрепления. 1232 год Statutum in favorem principum в основном распространил эти привилегии на светские территории. Хотя многие из этих привилегий существовали и ранее, теперь они были предоставлены глобально и раз и навсегда, чтобы позволить немецким князьям поддерживать порядок к северу от Альп, пока Фридрих сосредоточился на Италии. В документе 1232 года впервые германские герцоги стали именоваться domini terræ, владельцами своих земель, что также является примечательным изменением в терминологии.

Королевство Богемия было значительной региональной державой в Средние века . В 1212 году король Оттокар I (носивший титул «король» с 1198 года) издал Золотую буллу Сицилии (официальный указ) от императора Фридриха II, подтверждающую королевский титул Оттокара и его потомков, и герцогство Богемия было повышено до королевства. [110] Политические и финансовые обязательства Богемии перед Империей постепенно сокращались. [111] Карл IV назначил Прагу резиденцией императора Священной Римской империи.

После смерти Фридриха II в 1250 году Германское королевство было разделено между его сыном Конрадом IV (умер в 1254 году) и антикоролем Вильгельмом Голландским (умер в 1256 году). За смертью Конрада последовало Междуцарствие , в течение которого ни один король не мог добиться всеобщего признания, что позволило принцам объединить свои владения и стать еще более независимыми как правители. После 1257 года корона оспаривалась между Ричардом Корнуоллом , которого поддерживала партия Гвельфов , и Альфонсо X Кастильским , которого признала партия Гогенштауфенов, но он никогда не ступал на немецкую землю. После смерти Ричарда в 1273 году был избран Рудольф I Германский , мелкий граф, поддерживающий Гогенштауфенов. Он был первым из Габсбургов , кто носил королевский титул, но он никогда не был коронован императором. После смерти Рудольфа в 1291 году Адольф и Альберт были еще двумя слабыми королями, которые так и не были коронованы как императоры.

Альберт был убит в 1308 году. Почти сразу же король Франции Филипп IV начал настойчиво искать поддержки для своего брата, Карла Валуа , чтобы избрать его следующим королем римлян. Филипп думал, что у него есть поддержка французского папы Климента V (основанного в Авиньоне в 1309 году), и что его перспективы привести империю в орбиту французского королевского дома были хорошими. Он щедро раздавал французские деньги в надежде подкупить немецких курфюрстов. Хотя Карл Валуа имел поддержку профранцузского Генриха, архиепископа Кельна , многие не хотели видеть расширение французской власти, и меньше всего Клемент V. Главным соперником Карла, по-видимому, был граф Пфальцграф Рудольф II .

Но курфюрсты, крупные территориальные магнаты, десятилетиями жившие без коронованного императора, были недовольны и Карлом, и Рудольфом. Вместо этого граф Генрих Люксембургский , с помощью своего брата, архиепископа Балдуина Трирского , был избран Генрихом VII шестью голосами во Франкфурте 27 ноября 1308 года. Хотя Генрих был вассалом короля Филиппа, он был связан немногими национальными узами и, таким образом, подходил в качестве компромиссного кандидата. Генрих VII был коронован королем в Ахене 6 января 1309 года и императором папой Климентом V 29 июня 1312 года в Риме, положив конец междуцарствию.

В течение 13-го века общее структурное изменение в том, как управлялась земля, подготовило сдвиг политической власти в сторону растущей буржуазии за счет аристократического феодализма , который будет характеризовать позднее Средневековье . Рост городов и возникновение нового класса бюргеров разрушили общественный, правовой и экономический порядок феодализма. [112]

Крестьяне все чаще должны были платить дань своим помещикам. Концепция собственности начала заменять более древние формы юрисдикции, хотя они все еще были очень тесно связаны друг с другом. На территориях (не на уровне Империи) власть становилась все более связанной: тот, кто владел землей, имел юрисдикцию, из которой вытекали другие полномочия. Юрисдикция в то время не включала законодательство, которое фактически не существовало вплоть до XV века. Судебная практика в значительной степени опиралась на традиционные обычаи или правила, описываемые как обычные.

В это время территории начали трансформироваться в предшественников современных государств. Процесс сильно различался среди различных земель и был наиболее продвинут на тех территориях, которые были почти идентичны землям древних германских племен, например , Бавария. Он был медленнее на тех разбросанных территориях, которые были основаны посредством имперских привилегий.

В XII веке Ганзейский союз утвердился как торговый и оборонительный союз торговых гильдий городов и поселков империи и всей северной и центральной Европы. Он доминировал в морской торговле в Балтийском море , Северном море и вдоль связанных судоходных рек. Каждый из присоединенных городов сохранял правовую систему своего суверена и, за исключением свободных имперских городов , имел лишь ограниченную степень политической автономии. К концу XIV века могущественный союз при необходимости отстаивал свои интересы военными средствами. Это достигло кульминации в войне с суверенным Королевством Дания с 1361 по 1370 год. Союз пришел в упадок после 1450 года. [i] [113] [114]

Трудности с избранием короля в конечном итоге привели к появлению постоянной коллегии курфюрстов ( Kurfürsten ), состав и процедуры которой были изложены в Золотой булле 1356 года , изданной Карлом IV (правил в 1355–1378 годах, король римлян с 1346 года), которая оставалась в силе до 1806 года. Такое развитие событий, вероятно, лучше всего символизирует возникающую двойственность между императором и королевством ( Kaiser und Reich ), которые больше не считались идентичными. Золотая булла также излагала систему выборов императора Священной Римской империи. Теперь император должен был избираться большинством голосов, а не согласием всех семи курфюрстов. Для курфюрстов титул стал наследственным, и им было предоставлено право чеканить монеты и осуществлять юрисдикцию. Также рекомендовалось, чтобы их сыновья изучали императорские языки — немецкий , латынь , итальянский и чешский . [j] [16] Решение Карла IV является предметом дебатов: с одной стороны, оно помогло восстановить мир на землях Империи, которые были охвачены гражданскими конфликтами после окончания эпохи Гогенштауфенов; с другой стороны, «удар по центральной власти был несомненным». [115] Томас Брэди-младший полагает, что намерением Карла IV было положить конец спорным королевским выборам (с точки зрения Люксембургов, у них также было преимущество, что король Богемии имел постоянный и выдающийся статус как один из курфюрстов). [116] [117] В то же время он создал Богемию как основную землю Люксембургов в Империи и их династическую базу. Его правление в Богемии часто считается Золотым веком земли. Однако, по словам Брэди-младшего, под всем этим блеском возникла одна проблема: правительство показало неспособность справиться с волнами немецких иммигрантов в Богемии, что привело к религиозной напряженности и преследованиям. Имперский проект Люксембурга остановился при сыне Карла Венцеславе (правил в 1378–1419 годах как король Богемии, в 1376–1400 годах как король римлян), который также столкнулся с оппозицией со стороны 150 местных баронских семей. [118]

The shift in power away from the emperor is also revealed in the way the post-Hohenstaufen kings attempted to sustain their power. Earlier, the Empire's strength (and finances) greatly relied on the Empire's own lands, the so-called Reichsgut, which always belonged to the king of the day and included many Imperial Cities. After the 13th century, the relevance of the Reichsgut faded, even though some parts of it did remain until the Empire's end in 1806. Instead, the Reichsgut was increasingly pawned to local dukes, sometimes to raise money for the Empire, but more frequently to reward faithful duty or as an attempt to establish control over the dukes. The direct governance of the Reichsgut no longer matched the needs of either the king or the dukes.

The kings beginning with Rudolf I of Germany increasingly relied on the lands of their respective dynasties to support their power. In contrast with the Reichsgut, which was mostly scattered and difficult to administer, these territories were relatively compact and thus easier to control. In 1282, Rudolf I thus lent Austria and Styria to his own sons. In 1312, Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg was crowned as the first Holy Roman Emperor since Frederick II. After him all kings and emperors relied on the lands of their own family (Hausmacht): Louis IV of Wittelsbach (king 1314, emperor 1328–1347) relied on his lands in Bavaria; Charles IV of Luxembourg, the grandson of Henry VII, drew strength from his own lands in Bohemia. It was thus increasingly in the king's own interest to strengthen the power of the territories, since the king profited from such a benefit in his own lands as well.

The "constitution" of the Empire still remained largely unsettled at the beginning of the 15th century. Feuds often happened between local rulers. The "robber baron" (Raubritter) became a social factor.[119]

Simultaneously, the Catholic Church experienced crises of its own, with wide-reaching effects in the Empire. The conflict between several papal claimants (two anti-popes and the "legitimate" Pope) ended only with the Council of Constance (1414–1418); after 1419 the Papacy directed much of its energy to suppressing the Hussites. The medieval idea of unifying all Christendom into a single political entity, with the Church and the Empire as its leading institutions, began to decline.

With these drastic changes, much discussion emerged in the 15th century about the Empire itself. Rules from the past no longer adequately described the structure of the time, and a reinforcement of earlier Landfrieden was urgently needed.[120]

The vision for a simultaneous reform of the Empire and the Church on a central level began with Sigismund (reigned 1433–1437, King of the Romans since 1411), who, according to historian Thomas Brady Jr., "possessed a breadth of vision and a sense of grandeur unseen in a German monarch since the thirteenth century". But external difficulties, self-inflicted mistakes and the extinction of the Luxembourg male line made this vision unfulfilled.[121]

Frederick III was the first Habsburg to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor, in 1452.[122] He had been very careful regarding the reform movement in the empire. For most of his reign, he considered reform as a threat to his imperial prerogatives. He avoided direct confrontations, which might lead to humiliation if the princes refused to give way.[123] After 1440, the reform of the Empire and Church was sustained and led by local and regional powers, particularly the territorial princes.[124] In his last years, he felt more pressure on taking action from a higher level. Berthold von Henneberg, the Archbishop of Mainz, who spoke on behalf of reform-minded princes (who wanted to reform the Empire without strengthening the imperial hand), capitalized on Frederick's desire to secure the imperial election for his son Maximilian. Thus, in his last years, he presided over the initial phase of Imperial Reform, which would mainly unfold under his Maximilian. Maximilian himself was more open to reform, although naturally he also wanted to preserve and enhance imperial prerogatives. After Frederick retired to Linz in 1488, as a compromise, Maximilian acted as mediator between the princes and his father. When he attained sole rule after Frederick's death, he would continue this policy of brokerage, acting as the impartial judge between options suggested by the princes.[125][35]

Major measures for the Reform were launched at the 1495 Reichstag at Worms. A new organ was introduced, the Reichskammergericht, that was to be largely independent from the Emperor. A new tax was launched to finance it, the Gemeine Pfennig, although this would only be collected under Charles V and Ferdinand I, and not fully.[126][127][128]

To create a rival for the Reichskammergericht, in 1497 Maximilian establish the Reichshofrat, which had its seat in Vienna. During Maximilian's reign, this council was not popular though. In the long run, the two Courts functioned in parallel, sometimes overlapping.[129][130]

In 1500, Maximilian agreed to establish an organ called the Reichsregiment (central imperial government, consisting of twenty members including the Electors, with the Emperor or his representative as its chairman), first organized in 1501 in Nuremberg. But Maximilian resented the new organization, while the Estates failed to support it. The new organ proved politically weak, and its power returned to Maximilian in 1502.[131][130][132]

The most important governmental changes targeted the heart of the regime: the chancery. Early in Maximilian's reign, the Court Chancery at Innsbruck competed with the Imperial Chancery (which was under the elector-archbishop of Mainz, the senior Imperial chancellor). By referring the political matters in Tyrol, Austria as well as Imperial problems to the Court Chancery, Maximilian gradually centralized its authority. The two chanceries became combined in 1502.[7] In 1496, the emperor created a general treasury (Hofkammer) in Innsbruck, which became responsible for all the hereditary lands. The chamber of accounts (Raitkammer) at Vienna was made subordinate to this body.[133] Under Paul von Liechtenstein, the Hofkammer was entrusted with not only hereditary lands' affairs, but Maximilian's affairs as the German king too.[134]

At the 1495 Diet of Worms, the Reception of Roman Law was accelerated and formalized. The Roman Law was made binding in German courts, except in the case it was contrary to local statutes.[136] In practice, it became the basic law throughout Germany, displacing Germanic local law to a large extent, although Germanic law was still operative at the lower courts.[137][138][139][140] Other than the desire to achieve legal unity and other factors, the adoption also highlighted the continuity between the Ancient Roman empire and the Holy Roman Empire.[141] To realize his resolve to reform and unify the legal system, the emperor frequently intervened personally in matters of local legal matters, overriding local charters and customs. This practice was often met with irony and scorn from local councils, who wanted to protect local codes.[142]

The legal reform seriously weakened the ancient Vehmic court (Vehmgericht, or Secret Tribunal of Westphalia, traditionally held to be instituted by Charlemagne but this theory is now considered unlikely[143][144]), although it would not be abolished completely until 1811 (when it was abolished under the order of Jérôme Bonaparte).[145][146]

Maximilian and Charles V (despite the fact both emperors were internationalists personally[150][151]) were the first who mobilized the rhetoric of the Nation, firmly identified with the Reich by the contemporary humanists.[119] With encouragement from Maximilian and his humanists, iconic spiritual figures were reintroduced or became notable. The humanists rediscovered the work Germania, written by Tacitus. According to Peter H. Wilson, the female figure of Germania was reinvented by the emperor as the virtuous pacific Mother of Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.[152] Whaley further suggests that, despite the later religious divide, "patriotic motifs developed during Maximilian's reign, both by Maximilian himself and by the humanist writers who responded to him, formed the core of a national political culture."[153]

Maximilian's reign also witnessed the gradual emergence of the German common language, with the notable roles of the imperial chancery and the chancery of the Wettin Elector Frederick the Wise.[154][155] The development of the printing industry together with the emergence of the postal system (the first modern one in the world[156]), initiated by Maximilian himself with contribution from Frederick III and Charles the Bold, led to a revolution in communication and allowed ideas to spread. Unlike the situation in more centralized countries, the decentralized nature of the Empire made censorship difficult.[157][158][159][160]

Terence McIntosh comments that the expansionist, aggressive policy pursued by Maximilian I and Charles V at the inception of the early modern German nation (although not to further the aims specific to the German nation per se), relying on German manpower as well as utilizing fearsome Landsknechte and mercenaries, would affect the way neighbours viewed the German polity, although in the longue durée, Germany tended to be at peace.[161]

Maximilian was "the first Holy Roman Emperor in 250 years who ruled as well as reigned". In the early 1500s, he was true master of the Empire, although his power weakened during the last decade before his death.[162][163] Whaley notes that, despite struggles, what emerged at the end of Maximilian's rule was a strengthened monarchy and not an oligarchy of princes.[164] Benjamin Curtis opines that while Maximilian was not able to fully create a common government for his lands (although the chancellery and court council were able to coordinate affairs across the realms), he strengthened key administrative functions in Austria and created central offices to deal with financial, political and judicial matters – these offices replaced the feudal system and became representative of a more modern system that was administered by professionalized officials. After two decades of reforms, the emperor retained his position as first among equals, while the empire gained common institutions through which the emperor shared power with the estates.[165]

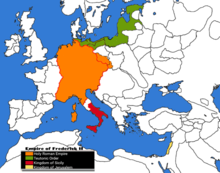

By the early 16th century, the Habsburg rulers had become the most powerful in Europe, but their strength relied on their composite monarchy as a whole, and not only the Holy Roman Empire (see also: Empire of Charles V).[166][167] Maximilian had seriously considered combining the Burgundian lands (inherited from his wife Mary of Burgundy) with his Austrian lands to form a powerful core (while also extending toward the east).[168] After the unexpected addition of Spain to the Habsburg Empire, at one point he intended to leave Austria (raised to a kingdom) to his younger grandson Ferdinand.[169] His elder grandson Charles V later gave Spain and most of the Burgundian lands to his son Philip II of Spain, the founder of the Spanish branch, and the Habsburg hereditary lands to his brother Ferdinand, the founder of the Austrian branch.[170]

In France and England, from the 13th century onward, stationary royal residences had begun to develop into capital cities that grew rapidly and developed corresponding infrastructure: the Palais de la Cité and the Palace of Westminster became the respective main residences. This was not possible in the Holy Roman Empire because no real hereditary monarchy emerged, but rather the tradition of elective monarchy prevailed (see: Imperial election) which, in the High Middle Ages, led to kings of very different regional origins being elected (List of royal and imperial elections in the Holy Roman Empire). If they wanted to control the empire and its rebellious regional rulers, they could not limit themselves to their home region and their private palaces. As a result, kings and emperors continued to travel around the empire well into modern times,[171] using their temporary residences (Kaiserpfalz) as transit stations for their itinerant courts. From the late Middle Ages onward, the weakly fortified pfalzen were replaced by imperial castles. It was only King Ferdinand I, the younger brother of the then Emperor Charles V, who moved his main residence to the Vienna Hofburg in the middle of the 16th century, where most of the following Habsburg emperors subsequently resided. Vienna did not become the capital of the empire, just of a Habsburg hereditary state (the Archduchy of Austria). The emperors continued to travel to their elections and coronations at Frankfurt and Aachen, to the Imperial Diets at different places and to other occasions. The Perpetual Diet of Regensburg was based in Regensburg from 1663 to 1806. Rudolf II resided in Prague, the Wittelsbach emperor Charles VII in Munich. A German capital in the true sense only existed in the Second German Empire from 1871, when the Kaiser, Reichstag and Reichskanzler resided in Berlin.

While particularism prevented the centralization of the Empire, it gave rise to early developments of capitalism. In Italian and Hanseatic cities like Genoa and Pisa, Hamburg and Lübeck, warrior-merchants appeared and pioneered raiding-and-trading maritime empires. These practices declined before 1500, but they managed to spread to the maritime periphery in Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands and England, where they "provoked emulation in grander, oceanic scale".[172] William Thompson agrees with M.N. Pearson that this distinctively European phenomenon happened because in the Italian and Hanseatic cities which lacked resources and were "small in size and population", the rulers (whose social status was not much higher than the merchants) had to pay attention to trade. Thus the warrior-merchants gained the state's coercive powers, which they could not gain in Mughal or other Asian realms – whose rulers had few incentives to help the merchant class, as they controlled considerable resources and their revenue was land-bound.[173]

In the 1450s, the economic development in Southern Germany gave rise to banking empires, cartels and monopolies in cities such as Ulm, Regensburg, and Augsburg. Augsburg in particular, associated with the reputation of the Fugger, Welser and Baumgartner families, is considered the capital city of early capitalism.[174][175] Augsburg benefitted majorly from the establishment and expansion of the Kaiserliche Reichspost in the late 15th and early 16th century.[157][156] Even when the Habsburg empire began to extend to other parts of Europe, Maximilian's loyalty to Augsburg, where he conducted a lot of his endeavours, meant that the imperial city became "the dominant centre of early capitalism" of the 16th century, and "the location of the most important post office within the Holy Roman Empire". From Maximilian's time, as the "terminuses of the first transcontinental post lines" began to shift from Innsbruck to Venice and from Brussels to Antwerp, in these cities, the communication system and the news market started to converge. As the Fuggers as well as other trading companies based their most important branches in these cities, these traders gained access to these systems as well.[176]The 1557, 1575 and 1607 bankruptcies of the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs though damaged the Fuggers substantially. Moreover, "Discovery of water routes to India and the New World shifted the focus of European economic development from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic – emphasis shifted from Venice and Genoa to Lisbon and Antwerp. Eventually American mineral developments reduced the importance of Hungarian and Tyrolean mineral wealth. The nexus of the European continent remained landlocked until the time of expedient land conveyances in the form of primarily rail and canal systems, which were limited in growth potential; in the new continent, on the other hand, there were ports in abundance to release the plentiful goods obtained from those new lands." The economic pinnacles achieved in Germany in the period between 1450 and 1550 would not be seen again until the end of the 19th century.[177]

In the Netherlands part of the empire, financial centres evolved together with markets of commodities. Topographical development in the 15th century made Antwerp a port city.[178] Boosted by the privileges it received as a loyal city after the Flemish revolts against Maximilian, it became the leading seaport city in Northern Europe and served as "the conduit for a remarkable 40% of world trade".[179][180][181] Conflicts with the Habsburg-Spanish government in 1576 and 1585 though made merchants relocate to Amsterdam, which eventually replaced it as the leading port city.[182][178]

.jpg/440px-Deutschland_im_XVI._Jahrhundert_(Putzger).jpg)

In 1516, Ferdinand II of Aragon, grandfather of the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, died.[183] Charles initiated his reign in Castile and Aragon, a union which evolved into Spain, in conjunction with his mother Joanna of Castile.

In 1519, already reigning as Carlos I in Spain, Charles took up the imperial title as Karl V. The Holy Roman Empire would end up going to a more junior branch of the Habsburgs in the person of Charles's brother Ferdinand, while the senior branch continued to rule in Spain and the Burgundian inheritance in the person of Charles's son, Philip II of Spain. Many factors contribute to this result. For James D. Tracy, it was the polycentric character of the European civilization that made it hard to maintain "a dynasty whose territories bestrode the continent from the Low Countries to Sicily and from Spain to Hungary – not to mention Spain's overseas possessions".[184] Others point out the religious tensions, fiscal problems and obstruction from external forces including France and the Ottomans.[185] On a more personal level, Charles failed to persuade the German princes to support his son Philip, whose "awkward and withdrawn character and lack of German language skills doomed this enterprise to failure".[186]

Before Charles's reign in the Holy Roman Empire began, in 1517, Martin Luther launched what would later be known as the Reformation. The empire then became divided along religious lines, with the north, the east, and many of the major cities – Strasbourg, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg – becoming Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Catholic.

At the beginning of Charles's reign, another Reichsregiment was set up again (1522), although Charles declared that he would only tolerate it in his absence and its chairman had to be a representative of his. Charles V was absent in Germany from 1521 to 1530. Similar to the one set up in the early 1500s, the Reichsregiment failed to create a federal authority independent of the emperor, due to the unsteady participation and differences between princes. Charles V defeated the Protestant princes in 1547 in the Schmalkaldic War, but the momentum was lost and the Protestant estates were able to survive politically despite military defeat.[187] In the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, Charles V, through his brother Ferdinand, officially recognized the right of rulers to choose Catholicism or Lutheranism (Zwinglians, Calvinists and radicals were not included).[188] In 1555, Paul IV was elected pope and took the side of France, whereupon an exhausted Charles finally gave up his hopes of a world Christian empire.[189][190]

Germany would enjoy relative peace for the next six decades. On the eastern front, the Turks continued to loom large as a threat, although war would mean further compromises with the Protestant princes, and so the Emperor sought to avoid it. In the west, the Rhineland increasingly fell under French influence. After the Dutch revolt against Spain erupted, the Empire remained neutral, de facto allowing the Netherlands to depart the empire in 1581. A side effect was the Cologne War, which ravaged much of the upper Rhine. Emperor Ferdinand III formally accepted Dutch neutrality in 1653, a decision ratified by the Reichstag in 1728.

After Ferdinand died in 1564, his son Maximilian II became Emperor, and like his father accepted the existence of Protestantism and the need for occasional compromise with it. Maximilian was succeeded in 1576 by Rudolf II, who preferred classical Greek philosophy to Christianity and lived an isolated existence in Bohemia. He became afraid to act when the Catholic Church was forcibly reasserting control in Austria and Hungary, and the Protestant princes became upset over this.

Imperial power sharply deteriorated by the time of Rudolf's death in 1612. When Bohemians rebelled against the Emperor, the immediate result was the series of conflicts known as the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which devastated the empire. Foreign powers, including France and Sweden, intervened in the conflict and strengthened those fighting the Imperial power, but also seized considerable territory for themselves. Accordingly, the empire could never return to its former glory, leading Voltaire to make his infamous quip that the Holy Roman Empire was "neither Holy nor Roman nor an Empire."[191]

Still, its actual end did not come for two centuries. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which ended the Thirty Years' War allowed Calvinism, but Anabaptists, Arminians and other Protestant communities would still lack any support and continue to be persecuted well until the end of the empire. The Habsburg emperors focused on consolidating their own estates in Austria and elsewhere.

At the Battle of Vienna (1683), the Army of the Holy Roman Empire, led by the Polish King John III Sobieski, decisively defeated a large Turkish army, stopping the western Ottoman advance and leading to the eventual dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in Europe. The army was one third forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and two thirds forces of the Holy Roman Empire.

By the rise of Louis XIV, the Habsburgs were chiefly dependent on their hereditary lands to counter the rise of Prussia, which possessed territories inside the Empire. Throughout the 18th century, the Habsburgs were embroiled in various European conflicts, such as the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), the War of the Polish Succession (1733–1735), and the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). The German dualism between Austria and Prussia dominated the empire's history after 1740.

From 1792 onward, revolutionary France was at war with various parts of the Empire intermittently.

The German mediatization was the series of mediatizations and secularizations that occurred between 1795 and 1814, during the latter part of the era of the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic Era. "Mediatization" was the process of annexing the lands of one imperial estate to another, often leaving the annexed some rights. For example, the estates of the Imperial Knights were formally mediatized in 1806, having de facto been seized by the great territorial states in 1803 in the so-called Rittersturm. "Secularization" was the abolition of the temporal power of an ecclesiastical ruler such as a bishop or an abbot and the annexation of the secularized territory to a secular territory.

The empire was dissolved on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805 (see Treaty of Pressburg). Napoleon reorganized much of the Empire into the Confederation of the Rhine, a French satellite. Francis' House of Habsburg-Lorraine survived the demise of the empire, continuing to reign as Emperors of Austria and Kings of Hungary until the Habsburg empire's final dissolution in 1918 in the aftermath of World War I.

The Napoleonic Confederation of the Rhine was replaced by a new union, the German Confederation in 1815, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. It lasted until 1866 when Prussia founded the North German Confederation, a forerunner of the German Empire which united the German-speaking territories outside of Austria and Switzerland under Prussian leadership in 1871. This state developed into modern Germany.

The abdication indicated that the Kaiser no longer felt capable of fulfilling his duties as head of the Reich, and so declared:

"That we consider the tie that has bound us to the body politic of the German Reich to be broken, that we have expired the office and dignity of the head of the Reich through the unification of the confederated Rhenish estates and that we are thereby relieved of all the duties we have assumed towards the German Reich Consider counted, and lay down the imperial crown worn by the same until now and conducted imperial government, as is hereby done."[192]

The only princely member states of the Holy Roman Empire that have preserved their status as monarchies until today are the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the Principality of Liechtenstein. The only Free Imperial Cities still existing as states within Germany are Hamburg and Bremen. All other historic member states of the Holy Roman Empire were either dissolved or have adopted republican systems of government.

Overall population figures for the Holy Roman Empire are extremely vague and vary widely. The empire of Charlemagne may have had as many as 20 million people.[193] Given the political fragmentation of the later Empire, there were no central agencies that could compile such figures. Nevertheless, it is believed the demographic disaster of the Thirty Years' War meant that the population of the Empire in the early 17th century was similar to what it was in the early 18th century; by one estimate, the Empire did not exceed 1618 levels of population until 1750.[194]

In the early 17th century, the electors held under their rule the following number of Imperial subjects:[195]

While not electors, the Spanish Habsburgs had the second highest number of subjects within the Empire after the Austrian Habsburgs, with over 3 million in the early 17th century in the Burgundian Circle and Duchy of Milan.[k][l]

Peter Wilson estimates the Empire's population at 20 million in 1700, of whom 5 million lived in Imperial Italy. By 1800 he estimates the Empire's population at 29 million (excluding Italy), with another 12.6 million held by the Austrians and Prussians outside of the Empire.[18]

According to a contemporary estimate of the Austrian War Archives for the first decade of the 18th century, the Empire – including Bohemia and the Spanish Netherlands – had a population of close to 28 million with a breakdown as follows:[198]

German demographic historians have traditionally worked on estimates of the population of the Holy Roman Empire based on assumed population within the frontiers of Germany in 1871 or 1914. More recent estimates use less outdated criteria, but they remain guesswork. One estimate based on the frontiers of Germany in 1870 gives a population of some 15–17 million around 1600, declined to 10–13 million around 1650 (following the Thirty Years' War). Other historians who work on estimates of the population of the early modern Empire suggest the population declined from 20 million to some 16–17 million by 1650.[199]

A credible estimate for 1800 gives 27–28 million inhabitants for the Empire (which at this point had already lost the remaining Low Countries, Italy, and the Left Bank of the Rhine in the 1797 Treaty of Campo Fornio) with an overall breakdown as follows:[200]

There are also numerous estimates for the Italian states that were formally part of the Empire:

Largest cities or towns of the Empire by year:

Catholicism constituted the single official religion of the Empire until 1555; the Holy Roman Emperor was always Catholic.

Lutheranism was officially recognized in the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, and Calvinism in the Peace of Westphalia of 1648. Those two constituted the only officially recognized Protestant denominations, while various other Protestant confessions such as Anabaptism, Arminianism, etc. coexisted illegally within the Empire. Anabaptism came in a variety of denominations, including Mennonites, Schwarzenau Brethren, Hutterites, the Amish, and multiple other groups.

Following the Peace of Augsburg, the official religion of a territory was determined by the principle cuius regio, eius religio according to which a ruler's religion determined that of his subjects. The Peace of Westphalia abrogated that principle by stipulating that the official religion of a territory was to be what it had been on 1 January 1624, considered to have been a "normal year". Henceforth, the conversion of a ruler to another faith did not entail the conversion of his subjects.[210]

In addition, all Protestant subjects of a Catholic ruler and vice versa were guaranteed the rights that they had enjoyed on that date. While the adherents of a territory's official religion enjoyed the right of public worship, the others were allowed the right of private worship (in chapels without either spires or bells). In theory, no one was to be discriminated against or excluded from commerce, trade, craft or public burial on grounds of religion. For the first time, the permanent nature of the division between the Christian churches of the empire was more or less assumed.[210]

A Jewish minority existed in the Holy Roman Empire. The Holy Roman Emperors claimed the right of protection and taxation of all the Jews of the empire, but there were also large-scale massacres of Jews, especially at the time of the First Crusade and during the wars of religion in the 16th century.

The Holy Roman Empire was neither a centralized state nor a nation-state. Instead, it was divided into dozens – eventually hundreds – of individual entities governed by kings,[p] dukes, counts, bishops, abbots, and other rulers, collectively known as princes. There were also some areas ruled directly by the Emperor.

From the High Middle Ages onwards, the Holy Roman Empire was marked by an uneasy coexistence with the princes of the local territories who were struggling to take power away from it. To a greater extent than in other medieval kingdoms such as France and England, the emperors were unable to gain much control over the lands that they formally owned. Instead, to secure their own position from the threat of being deposed, emperors were forced to grant more and more autonomy to local rulers, both nobles and bishops. This process began in the 11th century with the Investiture Controversy and was more or less concluded with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia. Several Emperors attempted to reverse this steady dilution of their authority but were thwarted both by the papacy and by the princes of the Empire.

The number of territories represented in the Imperial Diet was considerable, numbering about 300 at the time of the Peace of Westphalia. Many of these Kleinstaaten ("little states") covered no more than a few square miles, or included several non-contiguous pieces, so the Empire was often called a ‹See Tfd›Flickenteppich ("patchwork carpet"). An entity was considered a ‹See Tfd›Reichsstand (imperial estate) if, according to feudal law, it had no authority above it except the Holy Roman Emperor himself. The imperial estates comprised:

A sum total of 1,500 Imperial estates has been reckoned.[211] For a list of ‹See Tfd›Reichsstände in 1792, see List of Imperial Diet participants (1792).

The most powerful lords of the later empire were the Austrian Habsburgs, who ruled 240,000 km2 (93,000 sq mi) of land within the Empire in the first half of the 17th century, mostly in modern-day Austria and Czechia. At the same time the lands ruled by the electors of Saxony, Bavaria, and Brandenburg (prior to the acquisition of Prussia) were all close to 40,000 km2 (15,000 sq mi); the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (later the Elector of Hanover) had a territory around the same size. These were the largest of the German realms. The Elector of the Palatinate had significantly less at 20,000 km2 (7,700 sq mi), and the ecclesiastical Electorates of Mainz, Cologne, and Trier were much smaller, with around 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi). Just larger than them, with roughly 7,000–10,000 km2 (2,700–3,900 sq mi), were the Duchy of Württemberg, the Landgraviate of Hessen-Kassel, and the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. They were roughly matched in size by the prince-bishoprics of Salzburg and Münster. The majority of the other German territories, including the other prince-bishoprics, were under 5,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi), the smallest being those of the Imperial Knights; around 1790 the Knights consisted of 350 families ruling a total of only 5,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi) collectively.[212] Imperial Italy was less fragmented politically, most of it c. 1600 being divided between Savoy (Savoy, Piedmont, Nice, Aosta), the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (Tuscany, bar Lucca), the Republic of Genoa (Liguria, Corisca), the duchies of Modena-Reggio and Parma-Piacenza (Emilia), and the Spanish Duchy of Milan (most of Lombardy), each with between half a million and one and a half million people.[201] The Low Countries were also more coherent than Germany, being entirely under the dominion of the Spanish Netherlands as part of the Burgundian Circle, at least nominally.

2.JPG/440px-Weltliche_Schatzkammer_Wien_(189)2.JPG)

A prospective Emperor first had to be elected King of the Romans (Latin: Rex Romanorum; German: römischer König). German kings had been elected since the 9th century; at that point they were chosen by the leaders of the five most important tribes (the Salian Franks of Lorraine, Ripuarian Franks of Franconia, Saxons, Bavarians, and Swabians). In the Holy Roman Empire, the main dukes and bishops of the kingdom elected the King of the Romans.

The imperial throne was transferred by election, but Emperors often ensured their own sons were elected during their lifetimes, enabling them to keep the crown for their families. This only changed after the end of the Salian dynasty in the 12th century.

In 1356, Emperor Charles IV issued the Golden Bull, which limited the electors to seven: the King of Bohemia, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg, and the archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier. During the Thirty Years' War, the Duke of Bavaria was given the right to vote as the eighth elector, and the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (colloquially, Hanover) was granted a ninth electorate; additionally, the Napoleonic Wars resulted in several electorates being reallocated, but these new electors never voted before the Empire's dissolution. A candidate for election would be expected to offer concessions of land or money to the electors in order to secure their vote.

After being elected, the King of the Romans could theoretically claim the title of "Emperor" only after being crowned by the Pope. In many cases, this took several years while the King was held up by other tasks: frequently he first had to resolve conflicts in rebellious northern Italy or was quarreling with the Pope himself. Later Emperors dispensed with the papal coronation altogether, being content with the styling Emperor-Elect: the last Emperor to be crowned by the Pope was Charles V in 1530.

The Emperor had to be male and of noble blood. No law required him to be a Catholic, but as the majority of the Electors adhered to this faith, no Protestant was ever elected. Whether and to what degree he had to be German was disputed among the Electors, contemporary experts in constitutional law, and the public. During the Middle Ages, some Kings and Emperors were not of German origin, but since the Renaissance, German heritage was regarded as vital for a candidate in order to be eligible for imperial office.[214]

The Imperial Diet (Reichstag, or Reichsversammlung) was not a legislative body as is understood today, as its members envisioned it to be more like a central forum, where it was more important to negotiate than to decide.[215] The Diet was theoretically superior to the emperor himself. It was divided into three classes. The first class, the Council of Electors, consisted of the electors, or the princes who could vote for King of the Romans. The second class, the Council of Princes, consisted of the other princes. The Council of Princes was divided into two "benches", one for secular rulers and one for ecclesiastical ones. Higher-ranking princes had individual votes, while lower-ranking princes were grouped into "colleges" by geography. Each college had one vote.

The third class was the Council of Imperial Cities, which was divided into two colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. The Council of Imperial Cities was not fully equal with the others; it could not vote on several matters such as the admission of new territories. The representation of the Free Cities at the Diet had become common since the late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, their participation was formally acknowledged only as late as 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years' War.

The Empire also had two courts: the Reichshofrat (also known in English as the Aulic Council) at the court of the King/Emperor, and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court), established with the Imperial Reform of 1495 by Maximilian I. The Reichskammergericht and the Aulic Council were the two highest judicial instances in the Old Empire. The Imperial Chamber court's composition was determined by both the Holy Roman Emperor and the subject states of the Empire. Within this court, the Emperor appointed the chief justice, always a highborn aristocrat, several divisional chief judges, and some of the other puisne judges.[216]

The Aulic Council held standing over many judicial disputes of state, both in concurrence with the Imperial Chamber court and exclusively on their own. The provinces Imperial Chamber Court extended to breaches of the public peace, cases of arbitrary distraint or imprisonment, pleas which concerned the treasury, violations of the Emperor's decrees or the laws passed by the Imperial Diet, disputes about property between immediate tenants of the Empire or the subjects of different rulers, and finally suits against immediate tenants of the Empire, with the exception of criminal charges and matters relating to imperial fiefs, which went to the Aulic Council. The Aulic Council even allowed the emperors the means to depose rulers who did not live up to expectations.[130][129]

As part of the Imperial Reform, six Imperial circles were established in 1500; four more were established in 1512. These were regional groupings of most (though not all) of the various states of the Empire for the purposes of defense, imperial taxation, supervision of coining, peace-keeping functions, and public security. Each circle had its own parliament, known as a Kreistag ("Circle Diet"), and one or more directors, who coordinated the affairs of the circle. Not all imperial territories were included within the imperial circles, even after 1512; the Lands of the Bohemian Crown were excluded, as were Switzerland, the imperial fiefs in northern Italy, the lands of the Imperial Knights, and certain other small territories like the Lordship of Jever.

The Army of the Holy Roman Empire (‹See Tfd›German: Reichsarmee, ‹See Tfd›Reichsheer or ‹See Tfd›Reichsarmatur; Latin: exercitus imperii) was created in 1422 and as a result of the Napoleonic Wars came to an end even before the Empire. It should not be confused with the Imperial Army (‹See Tfd›Kaiserliche Armee) of the Emperor.

Despite appearances to the contrary, the Army of the Empire did not constitute a permanent standing army that was always at the ready to fight for the Empire. When there was danger, an Army of the Empire was mustered from among the elements constituting it,[217] in order to conduct an imperial military campaign or ‹See Tfd›Reichsheerfahrt. In practice, the imperial troops often had local allegiances stronger than their loyalty to the Emperor.

Throughout the first half of its history the Holy Roman Empire was reigned over by a travelling court. Kings and emperors toured between the numerous Kaiserpfalzes (Imperial palaces), usually resided for several weeks or months and furnished local legal matters, law and administration. Most rulers maintained one or a number of favourites Imperial palace sites, where they would advance development and spent most of their time: Charlemagne (Aachen from 794), Otto I (Magdeburg, from 955),[218] Frederick II (Palermo 1220–1254), Wittelsbacher (Munich 1328–1347 and 1744–1745), Habsburger (Prague 1355–1437 and 1576–1611; and Vienna 1438–1576, 1611–1740 and 1745–1806).[22][219][220]

This practice eventually ended during the 16th century, as the emperors of the Habsburg dynasty chose Vienna and Prague and the Wittelsbach rulers chose Munich as their permanent residences (Maximilian I's "true home" was still "the stirrup, the overnight rest and the saddle", although Innsbruck was probably his most important base; Charles V was also a nomadic emperor).[221][222][223] Vienna became Imperial capital during the 1550s under Ferdinand I (reigned 1556–1564). Except for a period under Rudolf II (reigned 1570–1612) who moved to Prague, Vienna kept its primacy under his successors.[221][224] Before that, certain sites served only as the individual residence for a particular sovereign. A number of cities held official status, where the Imperial Estates would summon at Imperial Diets, the deliberative assembly of the empire.[225][226]

The Imperial Diet (Reichstag) resided variously in Paderborn, Bad Lippspringe, Ingelheim am Rhein, Diedenhofen (now Thionville), Aachen, Worms, Forchheim, Trebur, Fritzlar, Ravenna, Quedlinburg, Dortmund, Verona, Minden, Mainz, Frankfurt am Main, Merseburg, Goslar, Würzburg, Bamberg, Schwäbisch Hall, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Quierzy-sur-Oise, Speyer, Gelnhausen, Erfurt, Eger (now Cheb), Esslingen, Lindau, Freiburg, Cologne, Konstanz and Trier before it was moved permanently to Regensburg.[227]

Until the 15th century the elected emperor was crowned and anointed by the Pope in Rome, among some exceptions in Ravenna, Bologna and Reims. Since 1508 (emperor Maximilian I) Imperial elections took place in Frankfurt am Main, Augsburg, Rhens, Cologne or Regensburg.[131][228]

In December 1497 the Aulic Council (Reichshofrat) was established in Vienna.[229]

In 1495 the Reichskammergericht was established, which variously resided in Worms, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Regensburg, Speyer and Esslingen before it was moved permanently to Wetzlar.[230]

The Habsburg royal family had its own diplomats to represent its interests. The larger principalities in the Holy Roman Empire, beginning around 1648, also did the same. The Holy Roman Empire did not have its own dedicated ministry of foreign affairs and therefore the Imperial Diet had no control over these diplomats; occasionally the Diet criticised them.[231]

When Regensburg served as the site of the Diet, France and, in the late 1700s, Russia, had diplomatic representatives there.[231] The kings of Denmark, Great Britain, and Sweden had land holdings in Germany and so had representation in the Diet itself.[232] The Netherlands also had envoys in Regensburg. Regensburg was the place where envoys met as it was where representatives of the Diet could be reached.[233]

Some constituencies of the Holy Roman Empire had additional royal or imperial territories that were, sometimes from the outset, outside the jurisdiction of the Holy Roman Empire. Henry VI, inheriting both German aspirations for imperial sovereignty and the Norman Sicilian kings' dream of hegemony in the Mediterranean, had ambitious design for a world empire. Boettcher remarks that marriage policy also played an important role here, "The marital policy of the Staufer ranged from Iberia to Russia, from Scandinavia to Sicily, from England to Byzantium and to the crusader states in the East. Henry was already casting his eyes beyond Africa and Greece, to Asia Minor and Syria and of course on Jerusalem." His annexation of Sicily changed the strategic balance in the Italian peninsula. The emperor, who wanted to make all his lands hereditary, also asserted that papal fiefs were imperial fiefs. On his death at the age of 31 though, he was unable to pass his powerful position to his son, Frederick II, who had only been elected King of the Romans.[234][235][236] The union between Sicily and the Empire thus remained personal union.[237] Frederick II became King of Sicily in 1225 through marriage to Isabella II (or Yolande) of Jerusalem and regained Bethlehem and Nazareth for the Christian side through negotiation with Al-Kamil. The Hohenstaufen dream of world empire ended with Frederick's death in 1250 though.[238][239]

In its earlier days, the Empire provided the principal medium for Christianity to infiltrate the pagans' realms in the North and the East (Scandinavians, Magyars, Slavic people etc.).[240] By the Reform era, the Empire, in its nature, was defensive and not aggressive, desiring of both internal peace and security against invading forces, a fact that even warlike princes such as Maximilian I appreciated.[241] In the Early Modern age, the association with the Church (the Church Universal for the Luxemburgs, and the Catholic Church for the Habsburgs) as well as the emperor's responsibility for the defence of Central Europe remained a reality though. Even the trigger for the conception of the Imperial Reform under Sigismund was the idea of helping the Church to put its house in order.[242][243][244]