Gasoline ( североамериканский английский ) или petrol ( содружество английский ) — нефтехимический продукт, характеризующийся как прозрачная, желтоватая и легковоспламеняющаяся жидкость, обычно используемая в качестве топлива для двигателей внутреннего сгорания с искровым зажиганием . При формулировании в качестве топлива для двигателей бензин химически состоит из органических соединений, полученных путем фракционной перегонки нефти , а затем химически улучшенных присадками к бензину . Это высокообъемный прибыльный продукт, производимый на нефтеперерабатывающих заводах. [1]

Топливные характеристики конкретной бензиновой смеси, которые будут противостоять слишком раннему воспламенению, измеряются как октановое число топливной смеси. Бензиновые смеси со стабильным октановым числом производятся в нескольких сортах топлива для различных типов двигателей. Топливо с низким октановым числом может вызвать детонацию двигателя и снижение эффективности поршневых двигателей . Тетраэтилсвинец и другие соединения свинца когда-то широко использовались в качестве добавок для повышения октанового числа, но не используются в современном автомобильном бензине из-за чрезвычайной опасности для здоровья , за исключением авиации, внедорожных транспортных средств и двигателей гоночных автомобилей . [2] [3]

Бензин может выбрасываться в окружающую среду Земли как несгоревшее жидкое топливо, как легковоспламеняющаяся жидкость или как пар в результате утечек, происходящих во время его производства, обработки, транспортировки и доставки. [4] Бензин содержит известные канцерогены , [5] [6] [7] и выхлопные газы бензина представляют опасность для здоровья. [8] Бензин часто используется в качестве рекреационного ингалятора и может быть вредным или смертельным при использовании таким образом. [9] При сжигании один литр (0,26 галлона США) бензина выделяет около 2,3 килограмма (5,1 фунта) CO2 , парникового газа , способствующего изменению климата, вызванному деятельностью человека . [10] [11] Нефтепродукты, включая бензин, были ответственны за около 32% выбросов CO2 во всем мире в 2021 году . [12]

В среднем, нефтеперерабатывающие заводы США производят около 19-20 галлонов бензина, 11-13 галлонов дистиллятного топлива дизельного топлива и 3-4 галлона реактивного топлива из каждого 42-галлонного (152-литрового) барреля сырой нефти. Соотношение продуктов зависит от переработки на нефтеперерабатывающем заводе и анализа сырой нефти . [13]

Американское английское слово petrol обозначает топливо для автомобилей , которое в обиходе сократилось до терминов gas или реже motor gas и mogas , что отличает его от avgas (авиационный бензин), который является топливом для самолетов. Английские словари, включая Oxford English Dictionary , показывают, что термин petrol происходит от gas плюс химические суффиксы -ole и -ine . [15] [16] [17] Однако в сообщении в блоге на несуществующем сайте Oxford Dictionaries альтернативно предлагается, что слово могло произойти от фамилии британского бизнесмена Джона Касселла , который предположительно первым вывел это вещество на рынок. [a]

Вместо слова «бензин» большинство стран Содружества (кроме Канады) используют термин «petrol», а североамериканцы в обиходе чаще используют «gas», отсюда и распространённость использования gas station в Соединённых Штатах. [18]

Происходящее из средневековой латыни , слово petrol (L. petra , камень + oleum , масло) изначально обозначало типы минерального масла, получаемого из горных пород и камней. [19] [20] В Великобритании Petrol был очищенным продуктом минерального масла, который продавался в качестве растворителя с 1870-х годов британским оптовым торговцем Carless Refining and Marketing Ltd. [ 21] Когда Petrol нашел позднее применение в качестве моторного топлива, Фредерик Симмс , партнер Готлиба Даймлера , предложил Джону Леонарду, владельцу Carless, зарегистрировать торговую марку на слово и заглавные буквы Petrol . [22] Заявка на регистрацию торговой марки была отклонена, поскольку petrol уже стал устоявшимся общим термином для моторного топлива. [23] Из-за возраста фирмы [ необходима ссылка ] Carless сохранила законные права на термин и написание заглавными буквами слова «Petrol» как наименования нефтехимического продукта. [24]

Первоначально британские нефтепереработчики использовали «моторный спирт» как общее название для автомобильного топлива и «авиационный спирт» для авиационного бензина . Когда в 1930-х годах Carless было отказано в регистрации торговой марки «petrol», его конкуренты перешли на более популярное название «petrol». Однако «моторный спирт» уже проник в законы и правила, поэтому этот термин по-прежнему используется как официальное название бензина. [25] [26] Термин наиболее широко используется в Нигерии, где крупнейшие нефтяные компании называют свой продукт «премиум моторный спирт». [27] Хотя «petrol» проник в нигерийский английский, «премиум моторный спирт» остается официальным названием, которое используется в научных публикациях, правительственных отчетах и газетах. [28]

Некоторые другие языки используют варианты слова petrol . Gasolina используется в испанском и португальском языках, а gasorin используется в японском языке. В других языках название продукта происходит от углеводородного соединения benzene или, точнее, от класса продуктов, называемых petrol benzine , например benzin в немецком или benzina в итальянском; но в Аргентине, Уругвае и Парагвае разговорное название nafta происходит от химического naphtha . [29]

В некоторых языках, например, французском и итальянском, для обозначения дизельного топлива используются соответствующие слова для бензина . [30]

Первые двигатели внутреннего сгорания, пригодные для использования в транспортных целях, так называемые двигатели Отто , были разработаны в Германии в последней четверти XIX века. Топливом для этих ранних двигателей был относительно летучий углеводород, полученный из угольного газа . С температурой кипения около 85 °C (185 °F) ( н -октан кипит при 125,62 °C (258,12 °F) [31] ), он хорошо подходил для ранних карбюраторов (испарителей). Разработка карбюратора с «распылительным соплом» позволила использовать менее летучие виды топлива. Дальнейшие улучшения эффективности двигателя были предприняты при более высоких степенях сжатия , но ранние попытки были заблокированы преждевременным взрывом топлива, известным как детонация .

В 1891 году крекинг-процесс Шухова стал первым в мире промышленным методом расщепления тяжелых углеводородов в сырой нефти с целью увеличения процента более легких продуктов по сравнению с простой перегонкой.

Эволюция бензина последовала за эволюцией нефти как доминирующего источника энергии в индустриальном мире. До Первой мировой войны Британия была крупнейшей промышленной державой мира и зависела от своего флота для защиты поставок сырья из своих колоний. Германия также индустриализировалась и, как и Британия, не имела многих природных ресурсов, которые нужно было доставлять в свою страну. К 1890-м годам Германия начала проводить политику мирового господства и начала строить флот, чтобы конкурировать с британским. Уголь был топливом, которое питало их флоты. Хотя и у Британии, и у Германии были природные запасы угля, новые разработки в области нефти как топлива для судов изменили ситуацию. Суда на угле были тактической слабостью, потому что процесс загрузки угля был чрезвычайно медленным и грязным и делал судно полностью уязвимым для атак, а ненадежные поставки угля в международных портах делали дальние плавания непрактичными. Преимущества нефтяного масла вскоре заставили флоты мира перейти на нефть, но у Британии и Германии было очень мало внутренних запасов нефти. [32] В конечном итоге Британия решила свою военно-морскую нефтяную зависимость, обеспечив себя нефтью от Royal Dutch Shell и Anglo-Persian Oil Company , и это определило, откуда и какого качества будет поступать ее бензин.

В ранний период развития бензиновых двигателей самолеты были вынуждены использовать автомобильный бензин, поскольку авиационного бензина еще не существовало. Эти ранние виды топлива назывались «прямогонными» бензинами и представляли собой побочные продукты перегонки одной сырой нефти для получения керосина , который был основным продуктом, используемым для сжигания в керосиновых лампах . Производство бензина не превзойдет производство керосина до 1916 года. Самые ранние прямогонные бензины были результатом перегонки сырой нефти с востока, и не было никакого смешивания дистиллятов из разных сортов сырой нефти. Состав этих ранних видов топлива был неизвестен, а качество сильно различалось, поскольку сырая нефть из разных месторождений появлялась в различных смесях углеводородов в разных соотношениях. Эффекты двигателя, вызванные ненормальным сгоранием ( стук двигателя и преждевременное зажигание ) из-за некачественного топлива, еще не были идентифицированы, и, как следствие, не было никакой оценки бензина с точки зрения его устойчивости к ненормальному сгоранию. Общей спецификацией, по которой измерялись ранние бензины, была удельная плотность по шкале Боме , а позднее летучесть (склонность к испарению), указанная в терминах точек кипения, которые стали основными фокусами для производителей бензина. Эти ранние восточные бензины из сырой нефти имели относительно высокие результаты теста Боме (от 65 до 80 градусов Боме) и назывались «пенсильванскими бензинами высокого теста» или просто «высокого теста». Их часто использовали в авиационных двигателях.

К 1910 году рост производства автомобилей и последующий рост потребления бензина привели к увеличению спроса на бензин. Кроме того, растущая электрификация освещения привела к падению спроса на керосин, создав проблему с поставками. Казалось, что растущая нефтяная промышленность окажется в ловушке перепроизводства керосина и недопроизводства бензина, поскольку простая перегонка не могла изменить соотношение двух продуктов из любой данной сырой нефти. Решение появилось в 1911 году, когда разработка процесса Бертона позволила проводить термический крекинг сырой нефти, что увеличило процент выхода бензина из более тяжелых углеводородов. Это сочеталось с расширением зарубежных рынков для экспорта излишков керосина, в которых внутренние рынки больше не нуждались. Считалось, что эти новые термически «крекинговые» бензины не имеют вредных эффектов и будут добавляться в бензины прямой перегонки. Также существовала практика смешивания тяжелых и легких дистиллятов для достижения желаемого показателя Боме, и все вместе они назывались «смешанными» бензинами. [33]

Постепенно летучесть приобрела преимущество над тестом Боме, хотя оба продолжали использоваться в сочетании для спецификации бензина. Еще в июне 1917 года Standard Oil (крупнейший переработчик сырой нефти в Соединенных Штатах в то время) заявила, что наиболее важным свойством бензина является его летучесть. [34] По оценкам, рейтинг эквивалента этих бензинов прямой перегонки варьировался от 40 до 60 октановых чисел, а «высокий тест», иногда называемый «боевым классом», вероятно, в среднем составлял от 50 до 65 октановых чисел. [35]

До вступления США в Первую мировую войну европейские союзники использовали топливо, полученное из сырой нефти с Борнео , Явы и Суматры , которое давало удовлетворительные характеристики их военным самолетам. Когда США вступили в войну в апреле 1917 года, США стали основным поставщиком авиационного бензина для союзников, и было отмечено снижение производительности двигателей. [36] Вскоре стало ясно, что автомобильное топливо неудовлетворительно для авиации, и после потери нескольких боевых самолетов внимание обратилось на качество используемых бензинов. Более поздние летные испытания, проведенные в 1937 году, показали, что снижение октанового числа на 13 пунктов (со 100 до 87 октанового числа) снижало производительность двигателя на 20 процентов и увеличивало взлетную дистанцию на 45 процентов. [37] Если бы произошло ненормальное сгорание, двигатель мог бы потерять достаточно мощности, чтобы сделать подъем в воздух невозможным, а взлетный разбег стал бы угрозой для пилота и самолета.

2 августа 1917 года Бюро горнодобывающей промышленности США организовало изучение топлива для самолетов в сотрудничестве с авиационным отделом Корпуса связи армии США , и общее обследование пришло к выводу, что надежных данных о надлежащем топливе для самолетов не существует. В результате на полях Лэнгли, МакКук и Райт начались летные испытания, чтобы определить, как различные бензины ведут себя в различных условиях. Эти испытания показали, что в некоторых самолетах автомобильные бензины ведут себя так же хорошо, как и «высокоточные», но в других типах приводили к перегреву двигателей. Было также обнаружено, что бензины из ароматических и нафтеновых базовых нефтей из Калифорнии, Южного Техаса и Венесуэлы приводили к плавной работе двигателей. Эти испытания привели к появлению первых правительственных спецификаций для автомобильных бензинов (авиационные бензины использовали те же спецификации, что и автомобильные бензины) в конце 1917 года. [38]

Конструкторы двигателей знали, что, согласно циклу Отто , мощность и эффективность увеличиваются со степенью сжатия, но опыт с ранними бензинами во время Первой мировой войны показал, что более высокие степени сжатия увеличивают риск ненормального сгорания, что приводит к снижению мощности, снижению эффективности, перегреву двигателей и потенциально серьезному повреждению двигателя. Чтобы компенсировать эти плохие виды топлива, ранние двигатели использовали низкие степени сжатия, что требовало относительно больших, тяжелых двигателей с ограниченной мощностью и эффективностью. Первый бензиновый двигатель братьев Райт использовал степень сжатия всего 4,7 к 1, развивал всего 8,9 киловатт (12 л. с.) из 3290 кубических сантиметров (201 куб. дюйм) и весил 82 килограмма (180 фунтов). [39] [40] Это было серьезной проблемой для конструкторов самолетов, и потребности авиационной промышленности спровоцировали поиск топлива, которое можно было бы использовать в двигателях с более высокой степенью сжатия.

В период с 1917 по 1919 год количество используемого термически крекированного бензина почти удвоилось. Кроме того, значительно возросло использование природного бензина . В этот период многие штаты США установили спецификации для автомобильного бензина, но ни один из них не пришел к согласию, и они были неудовлетворительными с той или иной точки зрения. Крупные нефтеперерабатывающие заводы начали указывать процент ненасыщенных материалов (термически крекированные продукты вызывали смолообразование как при использовании, так и при хранении, в то время как ненасыщенные углеводороды более реакционноспособны и имеют тенденцию соединяться с примесями, что приводит к смолообразованию). В 1922 году правительство США опубликовало первые спецификации для авиационных бензинов (две марки были обозначены как «боевые» и «бытовые» и регулировались точками кипения, цветом, содержанием серы и тестом на образование смолы) вместе с одной «моторной» маркой для автомобилей. Тест на смолообразование по сути исключил термически крекированный бензин из использования в авиации, и, таким образом, авиационные бензины вернулись к фракционированию прямогонных нафт или смешиванию прямогонных и высокоочищенных термически крекированных нафт. Такая ситуация сохранялась до 1929 года. [41]

Автомобильная промышленность отреагировала на увеличение термически крекированного бензина тревогой. Термический крекинг производил большое количество как моно- , так и диолефинов (ненасыщенных углеводородов), что увеличивало риск смолообразования. [42] Кроме того, летучесть снижалась до такой степени, что топливо не испарялось и прилипало к свечам зажигания и загрязняло их, создавая трудный запуск и неровную работу зимой, а также прилипая к стенкам цилиндров, обходя поршни и кольца и попадая в масло картера. [43] Один журнал утверждал, что «на многоцилиндровом двигателе в дорогом автомобиле мы разбавляем масло в картере на 40 процентов за 200 миль [320 км] пробега, как показывает анализ масла в масляном поддоне». [44]

Будучи очень недовольными последующим снижением общего качества бензина, производители автомобилей предложили ввести стандарт качества для поставщиков масла. Нефтяная промышленность, в свою очередь, обвинила автопроизводителей в том, что они не делают достаточно для улучшения экономичности транспортных средств, и спор стал известен в двух отраслях как «проблема топлива». Вражда между отраслями росла, каждая обвиняла другую в том, что они ничего не делают для решения проблем, и их отношения ухудшились. Ситуация была разрешена только тогда, когда Американский институт нефти (API) инициировал конференцию для решения проблемы топлива, и в 1920 году был создан кооперативный комитет по исследованию топлива (CFR) для надзора за совместными исследовательскими программами и решениями. Помимо представителей двух отраслей, Общество инженеров-автомобилестроителей (SAE) также сыграло важную роль, а Бюро стандартов США было выбрано в качестве беспристрастной исследовательской организации для проведения многих исследований. Первоначально все программы были связаны с испаряемостью и расходом топлива, легкостью запуска, разбавлением масла в картере и ускорением. [45]

С ростом использования термически крекинговых бензинов возросла обеспокоенность относительно их влияния на аномальное сгорание, и это привело к исследованиям антидетонационных присадок. В конце 1910-х годов такие исследователи, как AH Gibson, Harry Ricardo , Thomas Midgley Jr. и Thomas Boyd, начали исследовать аномальное сгорание. Начиная с 1916 года, Charles F. Kettering из General Motors начал исследовать присадки на основе двух путей: «высокопроцентного» раствора (где добавлялись большие количества этанола ) и «низкопроцентного» раствора (где требовалось всего 0,53–1,1 г/л или 0,071–0,147 унций/галлон США). «Низкопроцентное» решение в конечном итоге привело к открытию тетраэтилсвинца (TEL) в декабре 1921 года, продукта исследований Midgley и Boyd и определяющего компонента этилированного бензина. Это нововведение положило начало циклу улучшений в топливной эффективности , совпавшему с масштабным развитием нефтепереработки для производства большего количества продуктов в диапазоне кипения бензина. Этанол нельзя было запатентовать, а ТЭЛ можно, поэтому Кеттеринг получил патент на ТЭЛ и начал продвигать его вместо других вариантов.

Опасность соединений, содержащих свинец , к тому времени была хорошо известна, и Кеттеринг был напрямую предупрежден Робертом Уилсоном из Массачусетского технологического института, Ридом Хантом из Гарварда, Янделлом Хендерсоном из Йельского университета и Эриком Краузе из Потсдамского университета в Германии о его использовании. Краузе много лет работал с тетраэтилсвинцом и назвал его «ползучим и вредоносным ядом», который убил члена его диссертационного комитета. [46] [47] 27 октября 1924 года газетные статьи по всей стране рассказали о рабочих на нефтеперерабатывающем заводе Standard Oil около Элизабет , штат Нью-Джерси, которые производили TEL и страдали от отравления свинцом . К 30 октября число погибших достигло пяти. [47] В ноябре Комиссия по труду Нью-Джерси закрыла нефтеперерабатывающий завод Bayway, и было начато расследование большого жюри, которое к февралю 1925 года не привело ни к каким обвинениям. Продажа этилированного бензина была запрещена в Нью-Йорке, Филадельфии и Нью-Джерси. General Motors , DuPont и Standard Oil, которые были партнерами в Ethyl Corporation , компании, созданной для производства TEL, начали утверждать, что не существует альтернатив этилированному бензину, которые бы поддерживали топливную экономичность и при этом предотвращали детонацию двигателя. После того, как несколько финансируемых промышленностью ошибочных исследований сообщили, что бензин, обработанный TEL, не является проблемой общественного здравоохранения, споры утихли. [47]

За пять лет до 1929 года было проведено большое количество экспериментов по различным методам испытаний для определения устойчивости топлива к ненормальному сгоранию. Оказалось, что детонация двигателя зависела от широкого спектра параметров, включая компрессию, момент зажигания, температуру цилиндра, двигатели с воздушным или водяным охлаждением, форму камеры, температуру впуска, бедные или богатые смеси и другие. Это привело к запутанному разнообразию тестовых двигателей, которые давали противоречивые результаты, и не существовало стандартной шкалы оценок. К 1929 году большинство производителей и потребителей авиационного бензина признали, что некий антидетонационный рейтинг должен быть включен в государственные спецификации. В 1929 году была принята шкала октанового рейтинга , а в 1930 году была установлена первая октановая спецификация для авиационного топлива. В том же году ВВС США в результате проведенных ими исследований указали топливо с октановым числом 87 для своих самолетов. [48]

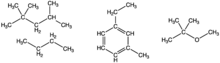

В этот период исследования показали, что структура углеводорода чрезвычайно важна для антидетонационных свойств топлива. Парафины с прямой цепью в диапазоне кипения бензина имели низкие антидетонационные качества, в то время как кольцевые молекулы, такие как ароматические углеводороды (например, бензол ), имели более высокую стойкость к детонации. [49] Это развитие привело к поиску процессов, которые производили бы больше этих соединений из сырой нефти, чем достигалось при прямой перегонке или термическом крекинге. Исследования основных нефтеперерабатывающих заводов привели к разработке процессов, включающих изомеризацию дешевого и распространенного бутана в изобутан и алкилирование для соединения изобутана и бутиленов с образованием изомеров октана , таких как « изооктан », который стал важным компонентом в смешивании авиационного топлива. Чтобы еще больше усложнить ситуацию, по мере увеличения производительности двигателя высота, которую мог достичь самолет, также увеличивалась, что привело к опасениям по поводу замерзания топлива. Среднее понижение температуры составляет 3,6 °F (2,0 °C) на каждые 300 метров (1000 футов) увеличения высоты, а на высоте 12 000 метров (40 000 футов) температура может приближаться к −57 °C (−70 °F). Такие присадки, как бензол, с температурой замерзания 6 °C (42 °F), замерзали бы в бензине и закупоривали бы топливные линии. Замещенные ароматические соединения, такие как толуол , ксилол и кумол , в сочетании с ограниченным количеством бензола решили эту проблему. [50]

К 1935 году существовало семь различных авиационных марок, основанных на октановом числе, две армейские марки, четыре военно-морские марки и три коммерческих марки, включая введение 100-октанового авиационного бензина. К 1937 году армия установила 100-октановое топливо в качестве стандартного топлива для боевых самолетов, и, чтобы добавить путаницы, правительство теперь признало 14 различных марок, в дополнение к 11 другим в зарубежных странах. Поскольку некоторые компании были обязаны иметь на складе 14 марок авиационного топлива, ни одна из которых не могла быть взаимозаменяемой, эффект для нефтеперерабатывающих заводов был негативным. Нефтеперерабатывающая промышленность не могла сосредоточиться на процессах конверсии большой мощности для такого количества различных марок, и нужно было найти решение. К 1941 году, в основном благодаря усилиям Комитета по исследованию кооперативного топлива, количество марок авиационного топлива было сокращено до трех: 73, 91 и 100 октан. [51]

Разработка 100-октанового авиационного бензина в экономически выгодных масштабах была отчасти обязана Джимми Дулиттлу , который стал авиационным менеджером Shell Oil Company. Он убедил Shell инвестировать в нефтеперерабатывающие мощности для производства 100-октанового бензина в масштабах, которые никому не были нужны, поскольку не существовало самолетов, которым требовалось топливо, которое никто не производил. Некоторые коллеги по работе назвали бы его усилия «ошибкой Дулиттла на миллион долларов», но время показало бы, что Дулиттл был прав. До этого армия рассматривала возможность проведения испытаний 100-октанового бензина с использованием чистого октана, но при цене 6,6 долл. за литр (25 долл./галлон США) цена не позволила этого сделать. В 1929 году компаниями Standard Oil из Калифорнии, Индианы и Нью-Джерси была организована компания Stanavo Specification Board Inc. для улучшения авиационных топлив и масел, а к 1935 году они выпустили на рынок свое первое 100-октановое топливо, Stanavo Ethyl Gasoline 100. Оно использовалось армией, производителями двигателей и авиакомпаниями для испытаний, а также для авиагонок и рекордных полетов. [52] К 1936 году испытания на аэродроме Райт-Филд с использованием новых, более дешевых альтернатив чистому октану доказали ценность 100-октанового топлива, и Shell и Standard Oil выиграли контракт на поставку тестовых партий для армии. К 1938 году цена снизилась до 0,046 долл. за литр (0,175 долл. за галлон США), что всего на 0,0066 долл. (0,025 долл.) больше, чем у 87-октанового топлива. К концу Второй мировой войны цена снизилась до 0,042 долл. за литр (0,16 долл. за галлон США). [53]

В 1937 году Юджин Хоудри разработал процесс каталитического крекинга Хоудри , который производил высокооктановый базовый бензин, превосходящий продукт термического крекинга, поскольку не содержал высокой концентрации олефинов. [33] В 1940 году в США работало всего 14 установок Хоудри; к 1943 году их число возросло до 77, как по процессу Хоудри, так и по типу Thermofor Catalytic или Fluid Catalyst. [54]

Поиск топлива с октановым числом выше 100 привел к расширению шкалы путем сравнения выходной мощности. Топливо, обозначенное как сорт 130, будет производить 130 процентов мощности в двигателе, работающем на чистом изооктане. Во время Второй мировой войны топливу с октановым числом выше 100 присваивались два рейтинга: богатая и бедная смесь, и они назывались «числами производительности» (PN). 100-октановый авиационный бензин будет называться сортом 130/100. [55]

Нефть и ее побочные продукты, особенно высокооктановый авиационный бензин, оказались движущей силой того, как Германия вела войну. В результате уроков Первой мировой войны Германия накопила нефть и бензин для своего молниеносного наступления и аннексировала Австрию, добавив 18 000 баррелей (2 900 м 3 ; 100 000 куб. футов) в день добычи нефти, но этого было недостаточно для поддержания запланированного завоевания Европы. Поскольку захваченные запасы и нефтяные месторождения были необходимы для подпитки кампании, немецкое высшее командование создало специальный отряд экспертов по нефтяным месторождениям, набранных из рядов отечественной нефтяной промышленности. Их отправили тушить пожары на нефтяных месторождениях и как можно скорее возобновлять добычу. Но захват нефтяных месторождений оставался препятствием на протяжении всей войны. Во время вторжения в Польшу немецкие оценки потребления бензина оказались значительно заниженными. Хайнц Гудериан и его танковые дивизии потребляли около 2,4 литра на километр (1 галлон США/миля) бензина по дороге в Вену . Когда они вступали в бой на открытой местности, потребление бензина почти удваивалось. На второй день битвы подразделение XIX корпуса было вынуждено остановиться, когда у него закончился бензин. [56] Одной из главных целей польского вторжения были их нефтяные месторождения, но Советы вторглись и захватили 70 процентов польской добычи, прежде чем немцы смогли добраться до них. Посредством германо-советского торгового соглашения (1940) Сталин в неопределенных выражениях согласился поставлять Германии дополнительную нефть, равную той, что добывается на теперь оккупированных Советским Союзом польских нефтяных месторождениях в Дрогобыче и Бориславе, в обмен на каменный уголь и стальные трубы.

Даже после того, как нацисты захватили огромные территории Европы, это не помогло решить проблему нехватки бензина. Этот регион никогда не был самодостаточным в плане поставок нефти до войны. В 1938 году территория, которая впоследствии была оккупирована нацистами, производила 575 000 баррелей (91 400 м 3 ; 3 230 000 куб. футов) в день. В 1940 году общее производство под контролем Германии составило всего 234 550 баррелей (37 290 м 3 ; 1 316 900 куб. футов). [57] К началу 1941 года и истощению немецких запасов бензина Адольф Гитлер видел во вторжении в Россию с целью захвата польских нефтяных месторождений и русской нефти на Кавказе решение проблемы нехватки бензина в Германии. Еще в июле 1941 года, после начала операции «Барбаросса» 22 июня , некоторые эскадрильи Люфтваффе были вынуждены сократить миссии наземной поддержки из-за нехватки авиационного бензина. 9 октября немецкий генерал-интендант подсчитал, что армейским транспортным средствам не хватает 24 000 баррелей (3 800 м 3 ; 130 000 куб. футов) бензина. [58] [ требуется уточнение (за какой период времени?) ]

Практически весь авиационный бензин Германии производился на заводах по производству синтетического масла, которые гидрогенизировали уголь и каменноугольную смолу. Эти процессы были разработаны в 1930-х годах в качестве попытки достичь топливной независимости. В Германии производилось два сорта авиационного бензина в больших объемах: B-4 или синий сорт и C-3 или зеленый сорт, на долю которых приходилось около двух третей всего производства. B-4 был эквивалентен 89-октановому бензину, а C-3 был примерно равен американскому 100-октановому бензину, хотя обедненная смесь оценивалась около 95-октанового бензина и была хуже, чем американская версия. Максимальная производительность, достигнутая в 1943 году, достигла 52 200 баррелей (8 300 м 3 ; 293 000 куб. футов) в день, прежде чем союзники решили нацелиться на заводы по производству синтетического топлива. Благодаря захваченным вражеским самолетам и анализу бензина, найденного в них, и союзники, и державы Оси были осведомлены о качестве производимого авиационного бензина, и это побудило гонку за октановым числом для достижения преимущества в летных характеристиках самолетов. Позже в ходе войны сорт C-3 был улучшен до уровня, эквивалентного сорту US 150 (рейтинг богатой смеси). [59]

Япония, как и Германия, почти не имела внутренних поставок нефти и к концу 1930-х годов производила только семь процентов своей собственной нефти, импортируя остальную часть — 80 процентов из США. По мере того, как японская агрессия в Китае росла ( инцидент с USS Panay ) и до американской общественности доходили новости о японских бомбардировках гражданских центров, особенно о бомбардировке Чунцина, общественное мнение начало поддерживать эмбарго США. Опрос Гэллапа в июне 1939 года показал, что 72 процента американской общественности поддерживали эмбарго на поставки военных материалов в Японию. Это усилило напряженность между США и Японией и привело к тому, что США ввели ограничения на экспорт. В июле 1940 года США выпустили прокламацию, запрещающую экспорт авиационного бензина с октановым числом 87 или выше в Японию. Этот запрет не мешал японцам, поскольку их самолеты могли работать с топливом с октановым числом ниже 87, и при необходимости они могли добавлять TEL для повышения октанового числа. Как оказалось, Япония закупила на 550 процентов больше авиационного бензина с октановым числом ниже 87 в течение пяти месяцев после запрета на продажу более высокооктанового бензина в июле 1940 года. [60] Возможность полного запрета бензина из Америки вызвала трения в японском правительстве относительно того, какие действия предпринять для обеспечения больших поставок из Голландской Ост-Индии, и потребовала большего экспорта нефти от изгнанного голландского правительства после битвы за Нидерланды . Это действие побудило США переместить свой Тихоокеанский флот из Южной Калифорнии в Перл-Харбор, чтобы помочь укрепить британскую решимость остаться в Индокитае. С японским вторжением во Французский Индокитай в сентябре 1940 года возникли большие опасения по поводу возможного японского вторжения в Голландскую Индию для обеспечения своей нефти. После того, как США запретили весь экспорт стального и железного лома, на следующий день Япония подписала Тройственный пакт , и это заставило Вашингтон опасаться, что полное нефтяное эмбарго США побудит японцев вторгнуться в Голландскую Ост-Индию. 16 июня 1941 года Гарольд Икес, назначенный координатором по нефти для национальной обороны, остановил поставку нефти из Филадельфии в Японию в связи с нехваткой нефти на Восточном побережье из-за возросшего экспорта союзникам. Он также телеграфировал всем поставщикам нефти на Восточном побережье не отправлять нефть в Японию без его разрешения. Президент Рузвельт отменил приказы Икеса, заявив Икесу, что «у меня просто нет достаточного количества флота, чтобы все сделать, и каждый небольшой эпизод в Тихом океане означает меньшее количество кораблей в Атлантике». [61] 25 июля 1941 года США заморозили все японские финансовые активы, и для каждого использования замороженных средств, включая закупки нефти, которые могли бы производить авиационный бензин, требовались лицензии. 28 июля 1941 года Япония вторглась в южный Индокитай.

Дебаты внутри японского правительства относительно ситуации с нефтью и бензином привели к вторжению в Голландскую Ост-Индию, но это означало бы войну с США, чей Тихоокеанский флот представлял угрозу их флангу. Эта ситуация привела к решению атаковать флот США в Перл-Харборе, прежде чем приступить к вторжению в Голландскую Ост-Индию. 7 декабря 1941 года Япония атаковала Перл-Харбор, а на следующий день Нидерланды объявили войну Японии, что инициировало Голландскую кампанию в Ост-Индии . Но японцы упустили золотую возможность в Перл-Харборе. «Вся нефть для флота находилась в надводных танках во время Перл-Харбора», — позже сказал адмирал Честер Нимиц, ставший главнокомандующим Тихоокеанским флотом. «У нас было около 4+1 ⁄ 2 миллиона баррелей [0,72 × 10 6 м 3 ; 25 × 10 6 куб. футов] нефти там, и вся она уязвима для пуль .50 калибра. Если бы японцы уничтожили нефть, — добавил он, — это продлило бы войну еще на два года». [62]

В начале 1944 года Уильям Бойд, президент Американского института нефти и председатель Военного совета нефтяной промышленности, сказал: «Союзники, возможно, плыли к победе на волне нефти в Первой мировой войне, но в этой бесконечно большей Второй мировой войне мы летим к победе на крыльях нефти». В декабре 1941 года в США было 385 000 нефтяных скважин, производящих 1,6 миллиарда баррелей (0,25 × 10 9 м 3 ; 9,0 × 10 9 куб. футов) нефти в год, а мощность по производству 100-октанового авиационного бензина составляла 40 000 баррелей (6 400 м 3 ; 220 000 куб. футов) в день. К 1944 году США производили более 1,5 млрд баррелей (0,24 × 10 9 м 3 ; 8,4 × 10 9 куб. футов) в год (67 процентов мирового производства), а нефтяная промышленность построила 122 новых завода по производству 100-октанового авиационного бензина, а мощность составляла более 400 000 баррелей (64 000 м 3 ; 2 200 000 куб. футов) в день — увеличение более чем в десять раз. Было подсчитано, что США производили достаточно 100-октанового авиационного бензина, чтобы позволить сбрасывать 16 000 метрических тонн (18 000 коротких тонн; 16 000 длинных тонн) бомб на противника каждый день в году. Учет потребления бензина армией до июня 1943 года был нескоординированным, поскольку каждая служба снабжения армии закупала собственные нефтепродукты, а централизованной системы контроля и учета не существовало. 1 июня 1943 года армия создала Отдел горюче-смазочных материалов Корпуса интендантства, и, исходя из их записей, они подсчитали, что армия (исключая горюче-смазочные материалы для самолетов) закупила более 9,1 миллиарда литров (2,4 × 10 9 галлонов США) бензина для поставок на зарубежные театры военных действий в период с 1 июня 1943 года по август 1945 года. Эта цифра не включает бензин, используемый армией внутри США [63]. Производство моторного топлива сократилось с 701 миллиона баррелей (111,5 × 10 6 м 3 ; 3940 × 10 6 куб. футов) в 1941 году до 208 миллионов баррелей (33,1 × 10 6 м 3 ; 1170 × 10 6 куб. футов) в 1943 году. [64]Вторая мировая война ознаменовала первый случай в истории США, когда бензин был нормирован, и правительство ввело контроль цен для предотвращения инфляции. Потребление бензина на автомобиль снизилось с 2860 литров (755 галлонов США) в год в 1941 году до 2000 литров (540 галлонов США) в 1943 году с целью сохранения резины для шин, поскольку японцы отрезали США от более чем 90 процентов поставок резины, которые поступали из Голландской Ост-Индии, а промышленность синтетического каучука в США находилась в зачаточном состоянии. Средние цены на бензин выросли с рекордно низкого уровня в 0,0337 долл. США за литр (0,1275 долл. США/галлон США) (0,0486 долл. США (0,1841 долл. США) с налогами) в 1940 году до 0,0383 долл. США за литр (0,1448 долл. США/галлон США) (0,0542 долл. США (0,2050 долл. США) с налогами) в 1945 году. [65]

Даже при самом большом в мире производстве авиационного бензина американские военные все равно обнаружили, что его нужно больше. На протяжении всей войны поставки авиационного бензина всегда отставали от потребностей, и это влияло на обучение и операции. Причина этого дефицита возникла еще до начала войны. Свободный рынок не поддерживал расходы на производство 100-октанового авиационного топлива в больших объемах, особенно во время Великой депрессии. Изооктан на ранней стадии разработки стоил 7,9 долл. за литр (30 долл./галлон США), и даже к 1934 году он все еще составлял 0,53 долл. за литр (2 долл./галлон США) по сравнению с 0,048 долл. (0,18 долл.) за автомобильный бензин, когда армия решила поэкспериментировать со 100-октановым бензином для своих боевых самолетов. Хотя только три процента боевых самолетов США в 1935 году могли в полной мере использовать преимущества более высокого октана из-за низкой степени сжатия, армия увидела, что потребность в повышении производительности оправдывает расходы, и закупила 100 000 галлонов. К 1937 году армия установила 100-октановое топливо в качестве стандартного топлива для боевых самолетов, а к 1939 году производство составило всего 20 000 баррелей (3 200 м 3 ; 110 000 куб. футов) в день. По сути, армия США была единственным рынком для 100-октанового авиационного бензина, и когда в Европе началась война, это создало проблему с поставками, которая сохранялась на протяжении всего периода. [66] [67]

С войной в Европе, которая стала реальностью в 1939 году, все прогнозы потребления 100-октанового бензина превосходили все возможное производство. Ни армия, ни флот не могли заключать контракты на топливо более чем на шесть месяцев вперед, и они не могли предоставить средства на расширение завода. Без долгосрочного гарантированного рынка нефтяная промышленность не стала бы рисковать своим капиталом для расширения производства продукта, который купит только правительство. Решением проблемы расширения хранения, транспортировки, финансов и производства стало создание Корпорации оборонных поставок 19 сентября 1940 года. Корпорация оборонных поставок должна была закупать, перевозить и хранить весь авиационный бензин для армии и флота по себестоимости плюс плата за перевозку. [68]

Когда прорыв союзников после дня Д обнаружил, что их армии растянули свои линии снабжения до опасной точки, временным решением стал Red Ball Express . Но даже этого вскоре оказалось недостаточно. Грузовикам в конвоях приходилось проезжать большие расстояния по мере продвижения армий, и они потребляли больший процент того же самого бензина, который пытались доставить. В 1944 году Третья армия генерала Джорджа Паттона наконец остановилась недалеко от границы с Германией из-за того, что у нее закончился бензин. Генерал был так расстроен прибытием грузовика с пайками вместо бензина, что, как сообщалось, он закричал: «Черт, они посылают нам еду, когда знают, что мы можем сражаться без еды, но не без нефти». [69] Решение пришлось отложить до ремонта железнодорожных линий и мостов, чтобы более эффективные поезда могли заменить потребляющие бензин грузовые конвои.

Разработка реактивных двигателей, сжигающих топливо на основе керосина во время Второй мировой войны для самолетов, создала более производительную двигательную систему, чем двигатели внутреннего сгорания, и вооруженные силы США постепенно заменили свои поршневые боевые самолеты на реактивные самолеты. Это развитие по сути устранило бы военную потребность в постоянно растущем октановом топливе и исключило бы государственную поддержку нефтеперерабатывающей промышленности для продолжения исследований и производства такого экзотического и дорогого топлива. Коммерческая авиация медленнее адаптировалась к реактивному движению, и до 1958 года, когда Boeing 707 впервые поступил в коммерческую эксплуатацию, поршневые авиалайнеры все еще полагались на авиационный бензин. Но у коммерческой авиации были большие экономические проблемы, чем максимальная производительность, которую могли себе позволить военные. С ростом октанового числа росла и стоимость бензина, но постепенное увеличение эффективности становится меньше по мере увеличения степени сжатия. Эта реальность установила практический предел того, насколько высокие степени сжатия могли увеличиться относительно того, насколько дорогим станет бензин. [70] Последний раз произведенный в 1955 году, Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major использовал авиационный бензин 115/145 и производил 0,046 киловатт на кубический сантиметр (1 л. с./куб. дюйм) при степени сжатия 6,7 (турбонаддув увеличил бы это) и 0,45 килограмма (1 фунт) веса двигателя для производства 0,82 киловатт (1,1 л. с.). Для сравнения, двигателю братьев Райт требовалось почти 7,7 килограмма (17 фунтов) веса двигателя для производства 0,75 киловатт (1 л. с.).

Автомобильная промышленность США после Второй мировой войны не могла воспользоваться преимуществами высокооктанового топлива, доступного тогда. Степень сжатия автомобилей увеличилась с 5,3 к 1 в среднем в 1931 году до всего лишь 6,7 к 1 в 1946 году. Среднее октановое число обычного автомобильного бензина увеличилось с 58 до 70 за то же время. Военные самолеты использовали дорогие двигатели с турбонаддувом, которые стоили как минимум в 10 раз дороже за лошадиную силу, чем автомобильные двигатели, и их приходилось ремонтировать каждые 700–1000 часов. Автомобильный рынок не мог поддерживать такие дорогие двигатели. [71] Только в 1957 году первый американский производитель автомобилей смог массово производить двигатель, который производил бы одну лошадиную силу на кубический дюйм, вариант двигателя Chevrolet V-8 мощностью 283 л. с./283 кубических дюйма в Corvette. При цене в 485 долларов это был дорогой вариант, который могли себе позволить лишь немногие потребители, и он был бы интересен только ориентированному на производительность рынку потребителей, готовому платить за требуемое премиальное топливо. [72] Этот двигатель имел заявленную степень сжатия 10,5 к 1, а в спецификациях AMA 1958 года указывалось, что требуемое октановое число составляло 96–100 RON. [73] При весе 243 кг (535 фунтов) (1959 год с алюминиевым впуском) требовалось 0,86 кг (1,9 фунта) веса двигателя, чтобы выдать 0,75 киловатт (1 л. с.). [74]

В 1950-х годах нефтеперерабатывающие заводы начали фокусироваться на высокооктановом топливе, а затем в бензин стали добавлять моющие средства для очистки жиклеров в карбюраторах. В 1970-х годах возросло внимание к экологическим последствиям сжигания бензина. Эти соображения привели к постепенному отказу от TEL и замене его другими антидетонационными соединениями. Впоследствии был введен бензин с низким содержанием серы, отчасти для сохранения катализаторов в современных выхлопных системах. [75]

Коммерческий газ представляет собой смесь большого количества различных углеводородов. [76] Химический бензин производится для соответствия ряду спецификаций производительности двигателя, и возможны многие различные составы. Следовательно, точный химический состав бензина не определен. Спецификация производительности также меняется в зависимости от сезона, требуя менее летучих смесей летом, чтобы минимизировать потери от испарения. На нефтеперерабатывающем заводе состав меняется в зависимости от сырой нефти, из которой он производится, типа технологических установок, имеющихся на нефтеперерабатывающем заводе, способа эксплуатации этих установок и того, какие углеводородные потоки (смеси) нефтеперерабатывающий завод выбирает использовать при смешивании конечного продукта. [77]

Gasoline is produced in oil refineries. Roughly 72 liters (19 U.S. gal) of gasoline is derived from a 160-liter (42 U.S. gal) barrel of crude oil.[78] Material separated from crude oil via distillation, called virgin or straight-run gasoline, does not meet specifications for modern engines (particularly the octane rating; see below), but can be pooled to the gasoline blend.

The bulk of a typical gasoline consists of a homogeneous mixture of small, relatively lightweight hydrocarbons with between 4 and 12 carbon atoms per molecule (commonly referred to as C4–C12).[75] It is a mixture of paraffins (alkanes), olefins (alkenes), and napthenes (cycloalkanes). The use of the term paraffin in place of the standard chemical nomenclature alkane is particular to the oil industry. The actual ratio of molecules in any gasoline depends upon:

The various refinery streams blended to make gasoline have different characteristics. Some important streams include the following:

The terms above are the jargon used in the oil industry, and the terminology varies.

Currently, many countries set limits on gasoline aromatics in general, benzene in particular, and olefin (alkene) content. Such regulations have led to an increasing preference for alkane isomers, such as isomerate or alkylate, as their octane rating is higher than n-alkanes. In the European Union, the benzene limit is set at one percent by volume for all grades of automotive gasoline. This is usually achieved by avoiding feeding C6, in particular cyclohexane, to the reformer unit, where it would be converted to benzene. Therefore, only (desulfurized) heavy virgin naphtha (HVN) is fed to the reformer unit[77]

Gasoline can also contain other organic compounds, such as organic ethers (deliberately added), plus small levels of contaminants, in particular organosulfur compounds (which are usually removed at the refinery).

The specific gravity of gasoline ranges from 0.71 to 0.77,[79] with higher densities having a greater volume fraction of aromatics.[80] Finished marketable gasoline is traded (in Europe) with a standard reference of 0.755 kilograms per liter (6.30 lb/U.S. gal), (7,5668 lb/ imp gal) its price is escalated or de-escalated according to its actual density.[clarification needed] Because of its low density, gasoline floats on water, and therefore water cannot generally be used to extinguish a gasoline fire unless applied in a fine mist.

Quality gasoline should be stable for six months if stored properly, but can degrade over time. Gasoline stored for a year will most likely be able to be burned in an internal combustion engine without too much trouble. However, the effects of long-term storage will become more noticeable with each passing month until a time comes when the gasoline should be diluted with ever-increasing amounts of freshly made fuel so that the older gasoline may be used up. If left undiluted, improper operation will occur and this may include engine damage from misfiring or the lack of proper action of the fuel within a fuel injection system and from an onboard computer attempting to compensate (if applicable to the vehicle). Gasoline should ideally be stored in an airtight container (to prevent oxidation or water vapor mixing in with the gas) that can withstand the vapor pressure of the gasoline without venting (to prevent the loss of the more volatile fractions) at a stable cool temperature (to reduce the excess pressure from liquid expansion and to reduce the rate of any decomposition reactions). When gasoline is not stored correctly, gums and solids may result, which can corrode system components and accumulate on wet surfaces, resulting in a condition called "stale fuel". Gasoline containing ethanol is especially subject to absorbing atmospheric moisture, then forming gums, solids, or two phases (a hydrocarbon phase floating on top of a water-alcohol phase).

The presence of these degradation products in the fuel tank or fuel lines plus a carburetor or fuel injection components makes it harder to start the engine or causes reduced engine performance. On resumption of regular engine use, the buildup may or may not be eventually cleaned out by the flow of fresh gasoline. The addition of a fuel stabilizer to gasoline can extend the life of fuel that is not or cannot be stored properly, though removal of all fuel from a fuel system is the only real solution to the problem of long-term storage of an engine or a machine or vehicle. Typical fuel stabilizers are proprietary mixtures containing mineral spirits, isopropyl alcohol, 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene or other additives. Fuel stabilizers are commonly used for small engines, such as lawnmower and tractor engines, especially when their use is sporadic or seasonal (little to no use for one or more seasons of the year). Users have been advised to keep gasoline containers more than half full and properly capped to reduce air exposure, to avoid storage at high temperatures, to run an engine for ten minutes to circulate the stabilizer through all components prior to storage, and to run the engine at intervals to purge stale fuel from the carburetor.[75]

Gasoline stability requirements are set by the standard ASTM D4814. This standard describes the various characteristics and requirements of automotive fuels for use over a wide range of operating conditions in ground vehicles equipped with spark-ignition engines.

A gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine obtains energy from the combustion of gasoline's various hydrocarbons with oxygen from the ambient air, yielding carbon dioxide and water as exhaust. The combustion of octane, a representative species, performs the chemical reaction:

By weight, combustion of gasoline releases about 46.7 megajoules per kilogram (13.0 kWh/kg; 21.2 MJ/lb) or by volume 33.6 megajoules per liter (9.3 kWh/L; 127 MJ/U.S. gal; 121,000 BTU/U.S. gal), quoting the lower heating value.[81] Gasoline blends differ, and therefore actual energy content varies according to the season and producer by up to 1.75 percent more or less than the average.[82] On average, about 74 liters (20 U.S. gal) of gasoline are available from a barrel of crude oil (about 46 percent by volume), varying with the quality of the crude and the grade of the gasoline. The remainder is products ranging from tar to naphtha.[83]

A high-octane-rated fuel, such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), has an overall lower power output at the typical 10:1 compression ratio of an engine design optimized for gasoline fuel. An engine tuned for LPG fuel via higher compression ratios (typically 12:1) improves the power output. This is because higher-octane fuels allow for a higher compression ratio without knocking, resulting in a higher cylinder temperature, which improves efficiency. Also, increased mechanical efficiency is created by a higher compression ratio through the concomitant higher expansion ratio on the power stroke, which is by far the greater effect. The higher expansion ratio extracts more work from the high-pressure gas created by the combustion process. An Atkinson cycle engine uses the timing of the valve events to produce the benefits of a high expansion ratio without the disadvantages, chiefly detonation, of a high compression ratio. A high expansion ratio is also one of the two key reasons for the efficiency of diesel engines, along with the elimination of pumping losses due to throttling of the intake airflow.

The lower energy content of LPG by liquid volume in comparison to gasoline is due mainly to its lower density. This lower density is a property of the lower molecular weight of propane (LPG's chief component) compared to gasoline's blend of various hydrocarbon compounds with heavier molecular weights than propane. Conversely, LPG's energy content by weight is higher than gasoline's due to a higher hydrogen-to-carbon ratio.

Molecular weights of the species in the representative octane combustion are 114, 32, 44, and 18 for C8H18, O2, CO2, and H2O, respectively; therefore one kilogram (2.2 lb) of fuel reacts with 3.51 kilograms (7.7 lb) of oxygen to produce 3.09 kilograms (6.8 lb) of carbon dioxide and 1.42 kilograms (3.1 lb) of water.

Spark-ignition engines are designed to burn gasoline in a controlled process called deflagration. However, the unburned mixture may autoignite by pressure and heat alone, rather than igniting from the spark plug at exactly the right time, causing a rapid pressure rise that can damage the engine. This is often referred to as engine knocking or end-gas knock. Knocking can be reduced by increasing the gasoline's resistance to autoignition, which is expressed by its octane rating.

Octane rating is measured relative to a mixture of 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (an isomer of octane) and n-heptane. There are different conventions for expressing octane ratings, so the same physical fuel may have several different octane ratings based on the measure used. One of the best known is the research octane number (RON).

The octane rating of typical commercially available gasoline varies by country. In Finland, Sweden, and Norway, 95 RON is the standard for regular unleaded gasoline and 98 RON is also available as a more expensive option.

In the United Kingdom, over 95 percent of gasoline sold has 95 RON and is marketed as Unleaded or Premium Unleaded. Super Unleaded, with 97/98 RON and branded high-performance fuels (e.g., Shell V-Power, BP Ultimate) with 99 RON make up the balance. Gasoline with 102 RON may rarely be available for racing purposes.[84][85][86]

In the U.S., octane ratings in unleaded fuels vary between 85[87] and 87 AKI (91–92 RON) for regular, 89–90 AKI (94–95 RON) for mid-grade (equivalent to European regular), up to 90–94 AKI (95–99 RON) for premium (European premium).

As South Africa's largest city, Johannesburg, is located on the Highveld at 1,753 meters (5,751 ft) above sea level, the Automobile Association of South Africa recommends 95-octane gasoline at low altitude and 93-octane for use in Johannesburg because "The higher the altitude the lower the air pressure, and the lower the need for a high octane fuel as there is no real performance gain".[88]

Octane rating became important as the military sought higher output for aircraft engines in the late 1920s and the 1940s. A higher octane rating allows a higher compression ratio or supercharger boost, and thus higher temperatures and pressures, which translate to higher power output. Some scientists[who?] even predicted that a nation with a good supply of high-octane gasoline would have the advantage in air power. In 1943, the Rolls-Royce Merlin aero engine produced 980 kilowatts (1,320 hp) using 100 RON fuel from a modest 27 liters (1,600 cu in) displacement. By the time of Operation Overlord, both the RAF and USAAF were conducting some operations in Europe using 150 RON fuel (100/150 avgas), obtained by adding 2.5 percent aniline to 100-octane avgas.[89] By this time, the Rolls-Royce Merlin 66 was developing 1,500 kilowatts (2,000 hp) using this fuel.

Gasoline, when used in high-compression internal combustion engines, tends to auto-ignite or "detonate" causing damaging engine knocking (also called "pinging" or "pinking"). To address this problem, tetraethyl lead (TEL) was widely adopted as an additive for gasoline in the 1920s. With a growing awareness of the seriousness of the extent of environmental and health damage caused by lead compounds, however, and the incompatibility of lead with catalytic converters, governments began to mandate reductions in gasoline lead.

In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency issued regulations to reduce the lead content of leaded gasoline over a series of annual phases, scheduled to begin in 1973 but delayed by court appeals until 1976. By 1995, leaded fuel accounted for only 0.6 percent of total gasoline sales and under 1,800 metric tons (2,000 short tons; 1,800 long tons) of lead per year. From 1 January 1996, the U.S. Clean Air Act banned the sale of leaded fuel for use in on-road vehicles in the U.S. The use of TEL also necessitated other additives, such as dibromoethane.

European countries began replacing lead-containing additives by the end of the 1980s, and by the end of the 1990s, leaded gasoline was banned within the entire European Union with an exception for Avgas 100LL for general aviation.[90] The UAE started to switch to unleaded in the early 2000s.[91]

Reduction in the average lead content of human blood may be a major cause for falling violent crime rates around the world[92] including South Africa.[93] A study found a correlation between leaded gasoline usage and violent crime (see Lead–crime hypothesis).[94][95] Other studies found no correlation.

In August 2021, the UN Environment Programme announced that leaded petrol had been eradicated worldwide, with Algeria being the last country to deplete its reserves. UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the eradication of leaded petrol an "international success story". He also added: "Ending the use of leaded petrol will prevent more than one million premature deaths each year from heart disease, strokes and cancer, and it will protect children whose IQs are damaged by exposure to lead". Greenpeace called the announcement "the end of one toxic era".[96] However, leaded gasoline continues to be used in aeronautic, auto racing, and off-road applications.[97] The use of leaded additives is still permitted worldwide for the formulation of some grades of aviation gasoline such as 100LL, because the required octane rating is difficult to reach without the use of leaded additives.

Different additives have replaced lead compounds. The most popular additives include aromatic hydrocarbons, ethers (MTBE and ETBE), and alcohols, most commonly ethanol.

Lead replacement petrol (LRP) was developed for vehicles designed to run on leaded fuels and incompatible with unleaded fuels. Rather than tetraethyllead, it contains other metals such as potassium compounds or methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT); these are purported to buffer soft exhaust valves and seats so that they do not suffer recession due to the use of unleaded fuel.

LRP was marketed during and after the phaseout of leaded motor fuels in the United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa, and some other countries.[vague] Consumer confusion led to a widespread mistaken preference for LRP rather than unleaded,[98] and LRP was phased out 8 to 10 years after the introduction of unleaded.[99]

Leaded gasoline was withdrawn from sale in Britain after 31 December 1999, seven years after EEC regulations signaled the end of production for cars using leaded gasoline in member states. At this stage, a large percentage of cars from the 1980s and early 1990s which ran on leaded gasoline were still in use, along with cars that could run on unleaded fuel. However, the declining number of such cars on British roads saw many gasoline stations withdrawing LRP from sale by 2003.[100]

Methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT) is used in Canada and the U.S. to boost octane rating.[101] Its use in the U.S. has been restricted by regulations, although it is currently allowed.[102] Its use in the European Union is restricted by Article 8a of the Fuel Quality Directive[103] following its testing under the Protocol for the evaluation of effects of metallic fuel-additives on the emissions performance of vehicles.[104]

Gummy, sticky resin deposits result from oxidative degradation of gasoline during long-term storage. These harmful deposits arise from the oxidation of alkenes and other minor components in gasoline[citation needed] (see drying oils). Improvements in refinery techniques have generally reduced the susceptibility of gasolines to these problems. Previously, catalytically or thermally cracked gasolines were most susceptible to oxidation. The formation of gums is accelerated by copper salts, which can be neutralized by additives called metal deactivators.

This degradation can be prevented through the addition of 5–100 ppm of antioxidants, such as phenylenediamines and other amines.[75] Hydrocarbons with a bromine number of 10 or above can be protected with the combination of unhindered or partially hindered phenols and oil-soluble strong amine bases, such as hindered phenols. "Stale" gasoline can be detected by a colorimetric enzymatic test for organic peroxides produced by oxidation of the gasoline.[105]

Gasolines are also treated with metal deactivators, which are compounds that sequester (deactivate) metal salts that otherwise accelerate the formation of gummy residues. The metal impurities might arise from the engine itself or as contaminants in the fuel.

Gasoline, as delivered at the pump, also contains additives to reduce internal engine carbon buildups, improve combustion and allow easier starting in cold climates. High levels of detergent can be found in Top Tier Detergent Gasolines. The specification for Top Tier Detergent Gasolines was developed by four automakers: GM, Honda, Toyota, and BMW. According to the bulletin, the minimal U.S. EPA requirement is not sufficient to keep engines clean.[106] Typical detergents include alkylamines and alkyl phosphates at a level of 50–100 ppm.[75]

In the EU, 5 percent ethanol can be added within the common gasoline spec (EN 228). Discussions are ongoing to allow 10 percent blending of ethanol (available in Finnish, French and German gasoline stations). In Finland, most gasoline stations sell 95E10, which is 10 percent ethanol, and 98E5, which is 5 percent ethanol. Most gasoline sold in Sweden has 5–15 percent ethanol added. Three different ethanol blends are sold in the Netherlands—E5, E10 and hE15. The last of these differs from standard ethanol–gasoline blends in that it consists of 15 percent hydrous ethanol (i.e., the ethanol–water azeotrope) instead of the anhydrous ethanol traditionally used for blending with gasoline.

The Brazilian National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP) requires gasoline for automobile use to have 27.5 percent of ethanol added to its composition.[107] Pure hydrated ethanol is also available as a fuel.

Legislation requires retailers to label fuels containing ethanol on the dispenser, and limits ethanol use to 10 percent of gasoline in Australia. Such gasoline is commonly called E10 by major brands, and it is cheaper than regular unleaded gasoline.

The federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) effectively requires refiners and blenders to blend renewable biofuels (mostly ethanol) with gasoline, sufficient to meet a growing annual target of total gallons blended. Although the mandate does not require a specific percentage of ethanol, annual increases in the target combined with declining gasoline consumption have caused the typical ethanol content in gasoline to approach 10 percent. Most fuel pumps display a sticker that states that the fuel may contain up to 10 percent ethanol, an intentional disparity that reflects the varying actual percentage. In parts of the U.S., ethanol is sometimes added to gasoline without an indication that it is a component.

In October 2007, the Government of India decided to make five percent ethanol blending (with gasoline) mandatory. Currently, 10 percent ethanol blended product (E10) is being sold in various parts of the country.[108][109] Ethanol has been found in at least one study to damage catalytic converters.[110]

Though gasoline is a naturally colorless liquid, many gasolines are dyed in various colors to indicate their composition and acceptable uses. In Australia, the lowest grade of gasoline (RON 91) was dyed a light shade of red/orange, but is now the same color as the medium grade (RON 95) and high octane (RON 98), which are dyed yellow.[111] In the U.S., aviation gasoline (avgas) is dyed to identify its octane rating and to distinguish it from kerosene-based jet fuel, which is left colorless.[112] In Canada, the gasoline for marine and farm use is dyed red and is not subject to fuel excise tax in most provinces.[113]

Oxygenate blending adds oxygen-bearing compounds such as MTBE, ETBE, TAME, TAEE, ethanol, and biobutanol. The presence of these oxygenates reduces the amount of carbon monoxide and unburned fuel in the exhaust. In many areas throughout the U.S., oxygenate blending is mandated by EPA regulations to reduce smog and other airborne pollutants. For example, in Southern California fuel must contain two percent oxygen by weight, resulting in a mixture of 5.6 percent ethanol in gasoline. The resulting fuel is often known as reformulated gasoline (RFG) or oxygenated gasoline, or, in the case of California, California reformulated gasoline (CARBOB). The federal requirement that RFG contain oxygen was dropped on 6 May 2006 because the industry had developed VOC-controlled RFG that did not need additional oxygen.[114]

MTBE was phased out in the U.S. due to groundwater contamination and the resulting regulations and lawsuits. Ethanol and, to a lesser extent, ethanol-derived ETBE are common substitutes. A common ethanol-gasoline mix of 10 percent ethanol mixed with gasoline is called gasohol or E10, and an ethanol-gasoline mix of 85 percent ethanol mixed with gasoline is called E85. The most extensive use of ethanol takes place in Brazil, where the ethanol is derived from sugarcane. In 2004, over 13 billion liters (3.4×109 U.S. gal) of ethanol was produced in the U.S. for fuel use, mostly from corn and sold as E10. E85 is slowly becoming available in much of the U.S., though many of the relatively few stations vending E85 are not open to the general public.[115]

The use of bioethanol and bio-methanol, either directly or indirectly by conversion of ethanol to bio-ETBE, or methanol to bio-MTBE is encouraged by the European Union Directive on the Promotion of the use of biofuels and other renewable fuels for transport. Since producing bioethanol from fermented sugars and starches involves distillation, though, ordinary people in much of Europe cannot legally ferment and distill their own bioethanol at present (unlike in the U.S., where getting a BATF distillation permit has been easy since the 1973 oil crisis).

The safety data sheet for a 2003 Texan unleaded gasoline shows at least 15 hazardous chemicals occurring in various amounts, including benzene (up to five percent by volume), toluene (up to 35 percent by volume), naphthalene (up to one percent by volume), trimethylbenzene (up to seven percent by volume), methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) (up to 18 percent by volume, in some states), and about 10 others.[116] Hydrocarbons in gasoline generally exhibit low acute toxicities, with LD50 of 700–2700 mg/kg for simple aromatic compounds.[117] Benzene and many antiknocking additives are carcinogenic.

People can be exposed to gasoline in the workplace by swallowing it, breathing in vapors, skin contact, and eye contact. Gasoline is toxic. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has also designated gasoline as a carcinogen.[118] Physical contact, ingestion, or inhalation can cause health problems. Since ingesting large amounts of gasoline can cause permanent damage to major organs, a call to a local poison control center or emergency room visit is indicated.[119]

Contrary to common misconception, swallowing gasoline does not generally require special emergency treatment, and inducing vomiting does not help, and can make it worse. According to poison specialist Brad Dahl, "even two mouthfuls wouldn't be that dangerous as long as it goes down to your stomach and stays there or keeps going". The U.S. CDC's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry says not to induce vomiting, lavage, or administer activated charcoal.[120][121]

Inhaled (huffed) gasoline vapor is a common intoxicant. Users concentrate and inhale gasoline vapor in a manner not intended by the manufacturer to produce euphoria and intoxication. Gasoline inhalation has become epidemic in some poorer communities and indigenous groups in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and some Pacific Islands.[122] The practice is thought to cause severe organ damage, along with other effects such as intellectual disability and various cancers.[123][124][125][126]

In Canada, Native children in the isolated Northern Labrador community of Davis Inlet were the focus of national concern in 1993, when many were found to be sniffing gasoline. The Canadian and provincial Newfoundland and Labrador governments intervened on several occasions, sending many children away for treatment. Despite being moved to the new community of Natuashish in 2002, serious inhalant abuse problems have continued. Similar problems were reported in Sheshatshiu in 2000 and also in Pikangikum First Nation.[127] In 2012, the issue once again made the news media in Canada.[128]

Australia has long faced a petrol (gasoline) sniffing problem in isolated and impoverished aboriginal communities. Although some sources argue that sniffing was introduced by U.S. servicemen stationed in the nation's Top End during World War II[129] or through experimentation by 1940s-era Cobourg Peninsula sawmill workers,[130] other sources claim that inhalant abuse (such as glue inhalation) emerged in Australia in the late 1960s.[131] Chronic, heavy petrol sniffing appears to occur among remote, impoverished indigenous communities, where the ready accessibility of petrol has helped to make it a common substance for abuse.

In Australia, petrol sniffing now occurs widely throughout remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, northern parts of South Australia, and Queensland.[132] The number of people sniffing petrol goes up and down over time as young people experiment or sniff occasionally. "Boss", or chronic, sniffers may move in and out of communities; they are often responsible for encouraging young people to take it up.[133] In 2005, the Government of Australia and BP Australia began the usage of Opal fuel in remote areas prone to petrol sniffing.[134] Opal is a non-sniffable fuel (which is much less likely to cause a high) and has made a difference in some indigenous communities.

Gasoline is extremely flammable due to its low flash point of −23 °C (−9 °F). Like other hydrocarbons, gasoline burns in a limited range of its vapor phase, and, coupled with its volatility, this makes leaks highly dangerous when sources of ignition are present. Gasoline has a lower explosive limit of 1.4 percent by volume and an upper explosive limit of 7.6 percent. If the concentration is below 1.4 percent, the air-gasoline mixture is too lean and does not ignite. If the concentration is above 7.6 percent, the mixture is too rich and also does not ignite. However, gasoline vapor rapidly mixes and spreads with air, making unconstrained gasoline quickly flammable.

The exhaust gas generated by burning gasoline is harmful to both the environment and to human health. After CO is inhaled into the human body, it readily combines with hemoglobin in the blood, and its affinity is 300 times that of oxygen. Therefore, the hemoglobin in the lungs combines with CO instead of oxygen, causing the human body to be hypoxic, causing headaches, dizziness, vomiting, and other poisoning symptoms. In severe cases, it may lead to death.[135][136] Hydrocarbons only affect the human body when their concentration is quite high, and their toxicity level depends on the chemical composition. The hydrocarbons produced by incomplete combustion include alkanes, aromatics, and aldehydes. Among them, a concentration of methane and ethane over 35 g/m3 (0.035 oz/cu ft) will cause loss of consciousness or suffocation, a concentration of pentane and hexane over 45 g/m3 (0.045 oz/cu ft) will have an anesthetic effect, and aromatic hydrocarbons will have more serious effects on health, blood toxicity, neurotoxicity, and cancer. If the concentration of benzene exceeds 40 ppm, it can cause leukemia, and xylene can cause headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Human exposure to large amounts of aldehydes can cause eye irritation, nausea, and dizziness. In addition to carcinogenic effects, long-term exposure can cause damage to the skin, liver, kidneys, and cataracts.[137] After NOx enters the alveoli, it has a severe stimulating effect on the lung tissue. It can irritate the conjunctiva of the eyes, cause tearing, and cause pink eyes. It also has a stimulating effect on the nose, pharynx, throat, and other organs. It can cause acute wheezing, breathing difficulties, red eyes, sore throat, and dizziness causing poisoning.[137][138] Fine particulates are also dangerous to health.[8]

In recent years, the rapid production of motor vehicles has significantly increased their use, thus leading to many serious environmental risks. The air pollution in many large cities has changed from coal-burning pollution to "motor vehicle pollution". In the U.S., transportation is the largest source of carbon emissions, accounting for 30 percent of the total carbon footprint of the U.S.[139] Combustion of gasoline produces 2.35 kilograms per liter (19.6 lb/U.S. gal) of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas.[140][141]

Unburnt gasoline and evaporation from the tank, when in the atmosphere, react in sunlight to produce photochemical smog. Vapor pressure initially rises with some addition of ethanol to gasoline, but the increase is greatest at 10 percent by volume.[142] At higher concentrations of ethanol above 10 percent, the vapor pressure of the blend starts to decrease. At a 10 percent ethanol by volume, the rise in vapor pressure may potentially increase the problem of photochemical smog. This rise in vapor pressure could be mitigated by increasing or decreasing the percentage of ethanol in the gasoline mixture. The chief risks of such leaks come not from vehicles, but gasoline delivery truck accidents and leaks from storage tanks. Because of this risk, most (underground) storage tanks now have extensive measures in place to detect and prevent any such leaks, such as monitoring systems (Veeder-Root, Franklin Fueling).

Production of gasoline consumes 1.5 liters per kilometer (0.63 U.S. gal/mi) of water by driven distance.[143]

Gasoline use causes a variety of deleterious effects to the human population and to the climate generally. The harms imposed include a higher rate of premature death and ailments, such as asthma, caused by air pollution, higher healthcare costs for the public generally, decreased crop yields, missed work and school days due to illness, increased flooding and other extreme weather events linked to global climate change, and other social costs. The costs imposed on society and the planet are estimated to be $3.80 per gallon of gasoline, in addition to the price paid at the pump by the user. The damage to the health and climate caused by a gasoline-powered vehicle greatly exceeds that caused by electric vehicles.[144][145]

About 2.353 kilograms per liter (19.64 lb/U.S. gal) of carbon dioxide (CO2) are produced from burning gasoline that does not contain ethanol.[141] Most of the retail gasoline now sold in the U.S. contains about 10 percent fuel ethanol (or E10) by volume.[141] Burning E10 produces about 2.119 kilograms per liter (17.68 lb/U.S. gal) of CO2 that is emitted from the fossil fuel content. If the CO2 emissions from ethanol combustion are considered, then about 2.271 kilograms per liter (18.95 lb/U.S. gal) of CO2 are produced when E10 is combusted.[141]

Worldwide 7 liters of gasoline are burnt for every 100 km driven by cars and vans.[146]

In 2021, the International Energy Agency stated, "To ensure fuel economy and CO2 emissions standards are effective, governments must continue regulatory efforts to monitor and reduce the gap between real-world fuel economy and rated performance."[146]

Gasoline enters the environment through the soil, groundwater, surface water, and air. Therefore, humans may be exposed to gasoline through methods such as breathing, eating, and skin contact. For example, using gasoline-filled equipment, such as lawnmowers, drinking gasoline-contaminated water close to gasoline spills or leaks to the soil, working at a gasoline station, inhaling gasoline volatile gas when refueling at a gasoline station is the easiest way to be exposed to gasoline.[147]

The International Energy Agency said in 2021 that "road fuels should be taxed at a rate that reflects their impact on people's health and the climate".[146]

Countries in Europe impose substantially higher taxes on fuels such as gasoline when compared to the U.S. The price of gasoline in Europe is typically higher than that in the U.S. due to this difference.[148]

From 1998 to 2004, the price of gasoline fluctuated between $0.26 and $0.53 per liter ($1 and $2/U.S. gal).[149] After 2004, the price increased until the average gasoline price reached a high of $1.09 per liter ($4.11/U.S. gal) in mid-2008 but receded to approximately $0.69 per liter ($2.60/U.S. gal) by September 2009.[149] The U.S. experienced an upswing in gasoline prices through 2011,[150] and, by 1 March 2012, the national average was $0.99 per liter ($3.74/U.S. gal). California prices are higher because the California government mandates unique California gasoline formulas and taxes.[151]

In the U.S., most consumer goods bear pre-tax prices, but gasoline prices are posted with taxes included. Taxes are added by federal, state, and local governments. As of 2009[update], the federal tax was $0.049 per liter ($0.184/U.S. gal) for gasoline and $0.064 per liter ($0.244/U.S. gal) for diesel (excluding red diesel).[152]

About nine percent of all gasoline sold in the U.S. in May 2009 was premium grade, according to the Energy Information Administration. Consumer Reports magazine says, "If [your owner's manual] says to use regular fuel, do so—there's no advantage to a higher grade."[153] The Associated Press said premium gas—which has a higher octane rating and costs more per gallon than regular unleaded—should be used only if the manufacturer says it is "required".[154] Cars with turbocharged engines and high compression ratios often specify premium gasoline because higher octane fuels reduce the incidence of "knock", or fuel pre-detonation.[155] The price of gasoline varies considerably between the summer and winter months.[156]