Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne disease caused by dengue virus, prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas. It is frequently asymptomatic; if symptoms appear they typically begin 3 to 14 days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin itching and skin rash. Recovery generally takes two to seven days. In a small proportion of cases, the disease develops into severe dengue (previously known as dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome)[8] with bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, blood plasma leakage, and dangerously low blood pressure.[1][2]

Dengue virus has four confirmed serotypes; infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term immunity to the others. Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe complications.[9] The symptoms of dengue resemble many other diseases including malaria, influenza, and Zika.[10] Blood tests are available to confirm the diagnosis including detecting viral RNA, or antibodies to the virus.[11]

There is no specific treatment for dengue fever. In mild cases, treatment is focused on treating pain symptoms. Severe cases of dengue require hospitalisation; treatment of acute dengue is supportive and includes giving fluid either by mouth or intravenously.[1][2]

Dengue is spread by several species of female mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, principally Aedes aegypti.[1] Infection can be prevented by mosquito elimination and the prevention of bites.[12] Two types of dengue vaccine have been approved and are commercially available. Dengvaxia became available in 2016 but it is only recommended to prevent re-infection in individuals who have been previously infected.[13] The second vaccine, Qdenga, became available in 2022 and is suitable for adults, adolescents and children from four years of age.[14]

The earliest descriptions of a dengue outbreak date from 1779; its viral cause and spread were understood by the early 20th century.[15] Already endemic in more than one hundred countries, dengue is spreading from tropical and subtropical regions to the Iberian Peninsula and the southern states of the US, partly attributed to climate change.[7][16] It is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[17] During 2023, more than 5 million infections were reported, with more than 5,000 dengue-related deaths.[7] As most cases are asymptomatic or mild, the actual numbers of dengue cases and deaths are under-reported.[7]

Typically, people infected with dengue virus are asymptomatic (80%) or have only mild symptoms such as an uncomplicated fever.[18][19] Others have more severe illness (5%), and in a small proportion it is life-threatening.[18][19] The incubation period (time between exposure and onset of symptoms) ranges from 3 to 14 days, but most often it is 4 to 7 days.[20]

The characteristic symptoms of mild dengue are sudden-onset fever, headache (typically located behind the eyes), muscle and joint pains, nausea, vomiting, swollen glands and a rash.[1][12] If this progresses to severe dengue the symptoms are severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, rapid breathing, bleeding gums or nose, fatigue, restlessness, blood in vomit or stool, extreme thirst, pale and cold skin, and feelings of weakness.[1]

The course of infection is divided into three phases: febrile, critical, and recovery.[21]

The febrile phase involves high fever (40 °C/104 °F), and is associated with generalized pain and a headache; this usually lasts two to seven days.[22][1] There may also be nausea, vomiting, a rash, and pains in the muscle and joints.[1]

Most people recover within a week or so. In about 5% of cases, symptoms worsen and can become life-threatening. This is called severe dengue (formerly called dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome).[21][23] Severe dengue can lead to shock, internal bleeding, organ failure and even death.[24] Warning signs include severe stomach pain, vomiting, difficulty breathing, and blood in the nose, gums, vomit or stools.[24]

During this period, there is leakage of plasma from the blood vessels, together with a reduction in platelets.[24] This may result in fluid accumulation in the chest and abdominal cavity as well as depletion of fluid from the circulation and decreased blood supply to vital organs.[23]

The recovery phase usually lasts two to three days.[23] The improvement is often striking, and can be accompanied with severe itching and a slow heart rate.[23]

Complications following severe dengue include fatigue, somnolence, headache, concentration impairment and memory impairment.[21][25] A pregnant woman who develops dengue is at higher risk of miscarriage, low birth weight, and premature birth.[26]

Children and older individuals are at a risk of developing complications from dengue fever compared to other age groups; young children typically suffer from more intense symptoms. Concurrent infections with tropical diseases [27]like Zika[28] virus can worsen symptoms and make recovery more challenging.[citation needed]

Dengue virus (DENV) is an RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae; genus Flavivirus. Other members of the same genus include yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, and Zika virus. Dengue virus genome (genetic material) contains about 11,000 nucleotide bases, which code for the three structural protein molecules (C, prM and E) that form the virus particle and seven other protein molecules that are required for replication of the virus.[29][30] There are four confirmed strains of the virus, called serotypes, referred to as DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4. The distinctions between the serotypes are based on their antigenicity.[31]

Dengue virus is most frequently transmitted by the bite of mosquitos in the Aedes genus, particularly A. aegypti.[32] They prefer to feed at dusk and dawn,[33] but they may bite and thus spread infection at any time of day.[34] Other Aedes species that may transmit the disease include A. albopictus, A. polynesiensis and A. scutellaris. Humans are the primary host of the virus,[35] but it also circulates in nonhuman primates, and can infect other mammals.[36][37] An infection can be acquired via a single bite.[38]

For 2 to 10 days after becoming newly infected, a person's bloodstream will contain a high level of virus particles (the viremic period). A female mosquito that takes a blood meal from the infected host then propagates the virus in the cells lining its gut.[39] Over the next few days, the virus spreads to other tissues including the mosquito's salivary glands and is released into its saliva. Next time the mosquito feeds, the infectious saliva will be injected into the bloodstream of its victim, thus spreading the disease.[40] The virus seems to have no detrimental effect on the mosquito, which remains infected for life.[20]

Dengue can also be transmitted via infected blood products and through organ donation.[1] Vertical transmission (from mother to child) during pregnancy or at birth has been reported.[41]

The principal risk for infection with dengue is the bite of an infected mosquito.[42] This is more probable in areas where the disease is endemic, especially where there is high population density, poor sanitation, and standing water where mosquitoes can breed.[42] It can be mitigated by taking steps to avoid bites such as by wearing clothing that fully covers the skin, using mosquito netting while resting, and/or the application of insect repellent (DEET being the most effective).[38]

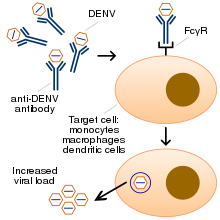

Chronic diseases – such as asthma, sickle cell anemia, and diabetes mellitus – increase the risk of developing a severe form of the disease.[43] Other risk factors for severe disease include female sex, and high body mass index,[21][30] Infection with one serotype is thought to produce lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term protection against the other three.[22] Subsequent re-infection with a different serotype increases the risk of severe complications due to phenomenon known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).[9][44]

The exact mechanism of ADE is not fully understood.[45] It appears that ADE occurs when the antibodies generated during an immune response recognize and bind to a pathogen, but they fail to neutralize it. Instead, the antibody-virus complex has an enhanced ability to bind to the Fcγ receptors of the target immune cells, enabling the virus to infect the cell and reproduce itself.[44][46]

When a mosquito carrying dengue virus bites a person, the virus enters the skin together with the mosquito's saliva. The virus infects nearby skin cells called keratinocytes, as well as specialized immune cell located in the skin, called a Langerhans cells.[47] The Langerhans cells migrate to the lymph nodes, where the infection spreads to white blood cells, and reproduces inside the cells while they move throughout the body.[48]

The white blood cells respond by producing several signaling proteins, such as cytokines and interferons, which are responsible for many of the symptoms, such as the fever, the flu-like symptoms, and the severe pains. In severe infection, the virus production inside the body is greatly increased, and many more organs (such as the liver and the bone marrow) can be affected. Fluid from the bloodstream leaks through the wall of small blood vessels into body cavities due to increased capillary permeability. As a result, blood volume decreases, and the blood pressure becomes so low that it cannot supply sufficient blood to vital organs. The spread of the virus to the bone marrow leads to reduced numbers of platelets, which are necessary for effective blood clotting; this increases the risk of bleeding, the other major complication of dengue fever.[48]

The principal risk for infection with dengue is the bite of an infected mosquito.[1] This is more probable in areas where the disease is endemic, especially where there is high population density, poor sanitation, and standing water where mosquitoes can breed.[42] It can be mitigated by taking steps to avoid bites such as by wearing clothing that fully covers the skin, using mosquito netting while resting, and/or the application of insect repellent (DEET being the most effective);[49] it is also advisable to treat clothing, nets and tents with 0.5% permethrin.[50]

Protection of the home can be achieved with door and window screens, by using air conditioning, and by regularly emptying and cleaning all receptacles both indoors and outdoors which may accumulate water (such as buckets, planters, pools or trashcans).[50]

The primary method of controlling A. aegypti is by eliminating its habitats. This is done by eliminating open sources of water, or if this is not possible, by adding insecticides or biological control agents to these areas. Generalized spraying with organophosphate or pyrethroid insecticides, while sometimes done, is not thought to be effective.[51] Reducing open collections of water through environmental modification is the preferred method of control, given the concerns of negative health effects from insecticides and greater logistical difficulties with control agents. Ideally, mosquito control would be a community activity, e.g. when all members of a community clear blocked gutters and street drains and keep their yards free of containers with standing water.[52] If residences have direct water connections this eliminates the need for wells or street pumps and water-carrying containers.[52]

As of March 2024, there are two vaccines to protect against dengue infection; Dengvaxia and Qdenga.[53]

Dengvaxia (formerly CYD-TDV) became available in 2015, and is approved for use in the US, EU and in some Asian and Latin American countries.[54] It is an attenuated virus, is suitable for individuals aged 6–45 years and protects against all four serotypes of dengue.[55] Due to safety concerns about antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), it should only be given to individuals who have previously been infected with dengue, in order to protect them from reinfection.[56] It is given subcutaneously as three doses at six month intervals.[57]

Qdenga (formerly TAK-003) completed clinical trials in 2022 and was approved for use in the European Union in December 2022;[53] it has been approved by a number of other countries including Indonesia and Brazil, and has been recommended by the SAGE committee of the World Health Organization.[58] It is indicated for the prevention of dengue disease in individuals four years of age and older, and can be administered to people who have not been previously infected with dengue. It is a live attenuated vaccine containing the four serotypes of dengue virus, administered subcutaneously as two doses three months apart.[53]

The World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases divides dengue fever into two classes: uncomplicated and severe.[18] Severe dengue is defined as that associated with severe bleeding, severe organ dysfunction, or severe plasma leakage.[59]

Severe dengue can develop suddenly, sometimes after a few days as the fever subsides.[24] Leakage of plasma from the capillaries results in extreme low blood pressure and hypovolemic shock; Patients with severe plasma leakage may have fluid accumulation in the lungs or abdomen, insufficient protein in the blood, or thickening of the blood. Severe dengue is a medical emergency which can cause damage to organs, leading to multiple organ failure and death.[60]

Mild cases of dengue fever can easily be confused with several common diseases including Influenza, measles, chikungunya, and zika.[61][62] Dengue, chikungunya and zika share the same mode of transmission (Aedes mosquitoes) and are often endemic in the same regions, so that it is possible to be infected simultaneously by more than one disease.[63] For travellers, dengue fever diagnosis should be considered in anyone who develops a fever within two weeks of being in the tropics or subtropics.[21]

Warning symptoms of severe dengue include abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, odema, bleeding, lethargy, and liver enlargement. Once again, these symptoms can be confused with other diseases such as malaria, gastroenteritis, leptospirosis, and typhus.[61]

Blood tests can be used to confirm a diagnosis of dengue. During the first few days of infection, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can be used to detect the NS1 antigen; however this antigen is produced by all flaviviruses.[63][11] Four or five days into the infection, it is possible to reliably detect anti-dengue IgM antibodies, but this does not determine the serotype.[63] Nucleic acid amplification tests provide the most reliable