В лингвистике грамматическая система рода — это специфическая форма системы классов существительных , где существительные отнесены к категориям рода, которые часто не связаны с реальными качествами сущностей, обозначаемых этими существительными. В языках с грамматическим родом большинство или все существительные изначально несут одно значение грамматической категории, называемой родом . [1] Значения, присутствующие в данном языке, которых обычно два или три, называются родами этого языка.

В то время как некоторые авторы используют термин «грамматический род» как синоним «класса существительного», другие используют разные определения для каждого из них. Многие авторы предпочитают «классы существительных», когда ни одно из словоизменений в языке не относится к полу или гендеру . Согласно одной оценке, гендер используется примерно в половине языков мира . [2] Согласно одному определению: «Гендер — это классы существительных, отраженные в поведении связанных с ними слов». [3] [4] [5]

В языках с грамматическим родом обычно имеется от двух до четырех различных родов, но в некоторых зафиксировано до 20 родов. [3] [6] [7]

Распространенные родовые деления включают мужской и женский род; мужской, женский и средний род; или одушевлённые и неодушевлённые.

В зависимости от языка и слова это назначение может иметь некоторую связь со значением существительного (например, «женщина» обычно женского рода) или может быть произвольным. [9] [10]

В некоторых языках отнесение любого конкретного существительного (т. е. именной лексемы, то есть набора форм существительных, склоняемых от общей леммы) к одному грамматическому роду определяется исключительно значением этого существительного или его атрибутами, такими как биологический пол, человечность или одушевленность. [11] [12] Однако существование слов, обозначающих мужской и женский пол, таких как разница между «тетя» и «дядя», недостаточно для формирования системы родов. [2]

В других языках разделение на роды обычно коррелирует в некоторой степени, по крайней мере для определенного набора существительных, таких как обозначающие людей, с некоторым свойством или свойствами вещей, которые обозначают определенные существительные. К таким свойствам относятся одушевленность или неодушевленность, « человечность » или «нечеловечность» и биологический пол .

Однако в большинстве языков это семантическое разделение верно лишь отчасти, и многие существительные могут относиться к категории рода, которая контрастирует с их значением, например, слово «мужественность» может быть женского рода, как во французском языке с «la masculinité» и «la virilité». [примечание 1] В таком случае на назначение рода также может влиять морфология или фонология существительного , или в некоторых случаях оно может быть, по-видимому, произвольным.

Обычно каждое существительное относится к одному из родов, и лишь немногие или ни одно существительное не может встречаться более чем в одном роде. [3] [6] [7]

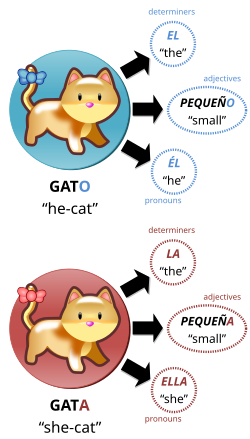

Гендер считается неотъемлемым качеством существительных, и он влияет на формы других родственных слов, процесс, называемый «согласованием» . Существительные можно считать «триггерами» процесса, тогда как другие слова будут «целью» этих изменений. [9]

Эти связанные слова могут быть, в зависимости от языка: определители , местоимения , числительные , квантификаторы , притяжательные местоимения , прилагательные , прошедшие и страдательные причастия , артикли , глаголы , наречия , комплементаторы и предлоги . Родовой класс может быть отмечен на самом существительном, но также всегда будет отмечен на других компонентах в именной фразе или предложении. Если существительное явно отмечено, как триггер, так и цель могут иметь похожие чередования. [6] [9] [10]

Три возможные функции грамматического рода включают в себя: [13]

Более того, грамматический род может служить для различения омофонов. Довольно распространенным явлением в развитии языка является слияние двух фонем , в результате чего этимологически разные слова звучат одинаково. Однако в языках с гендерным разделением эти пары слов все равно могут быть различимы по роду. Например, французские pot («горшок») и peau («кожа») являются омофонами /po/ , но не совпадают по роду: le pot vs. la peau .

Распространенные системы гендерного контраста включают: [14]

Существительные, обозначающие конкретно мужчин (или животных), обычно имеют мужской род; те, которые обозначают конкретно женщин (или животных), обычно имеют женский род; а существительные, обозначающие что-то, не имеющее пола, или не указывающие на пол своего референта, стали относиться к тому или иному роду, что может показаться произвольным. [9] [10] Примерами языков с такой системой являются большинство современных романских языков , балтийские языки , кельтские языки , некоторые индоарийские языки (например, хинди ) и афразийские языки .

Это похоже на системы с противопоставлением мужского и женского рода, за исключением того, что есть третий доступный род, поэтому существительные с бесполыми или неуказанными референтами пола могут быть мужского, женского или среднего рода. Существуют также некоторые исключительные существительные, род которых не следует за обозначенным полом, например, немецкое Mädchen , означающее «девочка», которое является средним. Это потому, что это на самом деле уменьшительное от «Magd», и все уменьшительные формы с суффиксом -chen являются средними. Примерами языков с такой системой являются более поздние формы праиндоевропейского (см. ниже), санскрит , некоторые германские языки , большинство славянских языков , несколько романских языков ( румынский , астурийский и неаполитанский ), маратхи , латынь и греческий .

Здесь существительные, обозначающие одушевленные предметы (людей и животных), обычно относятся к одному роду, а те, которые обозначают неодушевленные предметы, — к другому (хотя могут быть некоторые отклонения от этого принципа). Примерами служат более ранние формы протоиндоевропейского языка и самая ранняя семья, которая, как известно, отделилась от него, вымершие анатолийские языки (см. ниже). Современные примеры включают алгонкинские языки, такие как оджибве . [15]

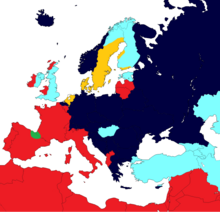

Здесь ранее существовала система мужской-женский-средний род, но различие между мужским и женским родом было утеряно в существительных (они слились в то, что называется общим родом ), хотя и не в местоимениях, которые могут работать под естественным родом. Таким образом, существительные, обозначающие людей, обычно имеют общий род, тогда как другие существительные могут быть любого рода. Примерами служат датский и шведский языки (см. Род в датском и шведском языках ), и в некоторой степени голландский язык (см. Род в голландской грамматике ).

В диалекте старой норвежской столицы Берген также используются только общий род и средний род. Общий род в Бергене и датском языке склоняется с помощью тех же артиклей и суффиксов, что и мужской род в норвежском букмоле . Из-за этого некоторые явно женские существительные, такие как «a cute girl», «the well milking cow» или «the pregnant mares», звучат странно для большинства норвежских ушей, когда их произносят датчане и жители Бергена, поскольку они склоняются таким образом, что звучат как склонения мужского рода в юго-восточных норвежских диалектах.

То же самое не относится к шведскому общему роду, поскольку склонения следуют другой схеме, чем в обоих норвежских письменных языках. Норвежский нюнорск , норвежский букмол и большинство разговорных диалектов сохраняют мужской, женский и средний род, даже если их скандинавские соседи утратили один из родов. Как показано, слияние мужского и женского рода в этих языках и диалектах можно считать отменой изначального разделения в праиндоевропейском (см. ниже).

Некоторые гендерные контрасты называются классами ; некоторые примеры см. в разделе Класс существительного . В некоторых славянских языках , например, в мужском, а иногда и женском и среднем родах, существует дальнейшее разделение между одушевленными и неодушевленными существительными, а в польском языке также иногда между существительными, обозначающими людей и не-людей. (Подробнее см. ниже.) Различие между человеком и не-человеком (или «рациональным и нерациональным») также встречается в дравидийских языках . (См. ниже.)

Было показано, что грамматический род вызывает ряд когнитивных эффектов. [16] Например, когда носителей гендерных языков просят представить себе говорящий неодушевленный объект, то, является ли его голос мужским или женским, как правило, соответствует грамматическому роду объекта в их языке. Это было замечено среди носителей испанского, французского и немецкого языков. [17] [18]

Предостережения этого исследования включают возможность «использования субъектами грамматического рода в качестве стратегии для выполнения задачи» [19] и тот факт, что даже для неодушевленных объектов род существительных не всегда случаен. Например, в испанском языке женский род часто приписывается объектам, которые «используются женщинами, естественными, круглыми или легкими», а мужской род — объектам, «используемым мужчинами, искусственными, угловатыми или тяжелыми». [18] Очевидные неудачи в воспроизведении эффекта для носителей немецкого языка также привели к предположению, что эффект ограничен языками с двухродовой системой, возможно, потому, что такие языки склонны к большему соответствию между грамматическим и естественным родом. [20] [18]

Другой вид теста просит людей описать существительное и пытается измерить, приобретает ли оно гендерно-специфические коннотации в зависимости от родного языка говорящего. Например, одно исследование показало, что носители немецкого языка, описывая мост ( нем . : Brücke , f. ), чаще использовали слова «красивый», «элегантный», «красивый» и «стройный», в то время как носители испанского языка, чье слово для моста мужского рода ( puente , m. ), чаще использовали слова «большой», «опасный», «сильный» и «крепкий». [21] Однако исследования такого рода подвергались критике по разным причинам и в целом давали неясную картину результатов. [17]

Существительное может принадлежать к данному классу из-за характерных особенностей его референта , таких как пол, одушевленность, форма, хотя в некоторых случаях существительное может быть помещено в определенный класс, основываясь исключительно на его грамматическом поведении. Некоторые авторы используют термин «грамматический род» как синоним «класса существительного», но другие используют разные определения для каждого из них.

Многие авторы предпочитают «классы существительных», когда ни одно из словоизменений в языке не относится к полу, например, когда проводится различие между одушевленным и неодушевленным. Обратите внимание, однако, что слово «гендер» происходит от латинского слова genus (также корня слова gener ), которое изначально означало «вид», поэтому оно не обязательно имеет сексуальное значение.

Классификатор, или мерное слово , — это слово или морфема, используемые в некоторых языках вместе с существительным, в основном для того, чтобы можно было применять числа и некоторые другие определители к существительному. Они не используются регулярно в английском или других европейских языках, хотя они параллельны использованию таких слов, как piece(s) и head в таких фразах, как «three Pieces of Paper» или «thirty head of cow». Они являются яркой особенностью восточноазиатских языков , где всем существительным обычно требуется классификатор при количественной оценке — например, эквивалентом «three people» часто является «three classifier people». Более общий тип классификатора ( classifier handshapes ) можно найти в языках жестов .

Классификаторы можно считать похожими на роды или классы существительных, поскольку язык, использующий классификаторы, обычно имеет несколько различных классификаторов, используемых с различными наборами существительных. Эти наборы в значительной степени зависят от свойств вещей, которые обозначают существительные (например, определенный классификатор может использоваться для длинных тонких объектов, другой для плоских объектов, третий для людей, третий для абстракций и т. д.), хотя иногда существительное ассоциируется с определенным классификатором скорее по соглашению, чем по какой-либо очевидной причине. Однако также возможно, что данное существительное может использоваться с любым из нескольких классификаторов; например, классификатор мандаринского китайского языка 个(個) gè часто используется в качестве альтернативы различным более конкретным классификаторам.

Грамматический род может быть реализован как словоизменение и может быть обусловлен другими типами словоизменения, особенно словоизменением по числу, где противопоставление единственного и множественного числа может взаимодействовать с словоизменением по роду.

Грамматический род существительного проявляется двумя основными способами: в модификациях, которым подвергается само существительное, и в модификациях других родственных слов ( согласование ).

Грамматический род проявляется, когда слова, связанные с существительным, такие как определители , местоимения или прилагательные, изменяют свою форму ( склоняются ) в соответствии с родом существительного, к которому они относятся ( согласование ). Части речи, на которые влияет согласование рода, обстоятельства, при которых это происходит, и способ обозначения рода слов различаются в разных языках. Склонение рода может взаимодействовать с другими грамматическими категориями, такими как число или падеж . В некоторых языках модель склонения, которой следует само существительное, будет разной для разных родов.

Род существительного может влиять на изменения, которым подвергается само существительное, в частности, на то, как существительное склоняется по числу и падежу . Например, в таких языках, как латинский , немецкий или русский, существует ряд различных моделей склонения, и то, какой модели следует конкретное существительное, может быть тесно связано с его родом. Для некоторых примеров этого см. Latin declension . Конкретным примером является немецкое слово See , которое имеет два возможных рода: когда оно мужского рода (что означает «озеро»), его родительный падеж единственного числа — Sees , но когда оно женского рода (что означает «море»), родительный падеж — See , потому что женские существительные не принимают родительный падеж -s .

Иногда пол отражается другими способами. В валлийском языке гендерная маркировка в основном теряется у существительных; однако в валлийском языке есть начальная мутация , когда первая согласная слова меняется на другую при определенных условиях. Пол является одним из факторов, которые могут вызвать одну форму мутации (мягкую мутацию). Например, слово merch "girl" меняется на ferch после определенного артикля . Это происходит только с существительными женского рода в единственном числе: mab "son" остается неизменным. Прилагательные подвержены влиянию пола аналогичным образом. [22]

Кроме того, во многих языках пол часто тесно связан с базовой немодифицированной формой ( леммой ) существительного, и иногда существительное может быть изменено, чтобы произвести (например) мужские и женские слова со схожим значением. См. § Морфологические критерии, основанные на форме, ниже.

Согласование , или конкорд, — это грамматический процесс, в котором определенные слова изменяют свою форму таким образом, что значения определенных грамматических категорий соответствуют значениям связанных с ними слов. Род — одна из категорий, которая часто требует согласования. В этом случае существительные можно считать «триггерами» процесса, поскольку они имеют присущий им род, тогда как родственные слова, которые изменяют свою форму, чтобы соответствовать роду существительного, можно считать «целью» этих изменений. [9]

Эти связанные слова могут быть, в зависимости от языка: определители , местоимения , числительные , квантификаторы , притяжательные местоимения , прилагательные , прошедшие и страдательные причастия , глаголы , наречия , комплементаторы и предлоги . Родовой класс может быть отмечен на самом существительном, но также может быть отмечен на других компонентах в именной фразе или предложении. Если существительное явно отмечено, как триггер, так и цель могут иметь похожие чередования. [6] [9] [10]

В качестве примера рассмотрим испанский язык , язык с двумя категориями рода: «естественный» и «грамматический». «Естественный» род может быть мужским или женским, [23] в то время как «грамматический» род может быть мужским, женским или средним. Этот третий, или «средний», род зарезервирован для абстрактных понятий, полученных от прилагательных: таких как lo bueno , lo malo («то, что хорошо/плохо»). Естественный род относится к биологическому полу большинства животных и людей, в то время как грамматический род относится к определенным фонетическим характеристикам (звукам в конце или начале) существительного. Среди других лексических единиц определенный артикль меняет свою форму в соответствии с этой категоризацией. В единственном числе артикль бывает: el (мужской) и la (женский). [примечание 2] [24] Таким образом, в «естественном роде» существительные, относящиеся к половым существам, которые являются существами мужского пола, несут мужской артикль, а существа женского пола — женский артикль (согласование). [25]

В «грамматическом» роде большинство слов, которые заканчиваются на -a , -d и -z, отмечены «женскими» артиклями, в то время как все остальные используют «родовые» или «мужские» артикли. [ необходима цитата ]

В некоторых языках род различается только в единственном числе, но не во множественном. С точки зрения языковой маркированности эти языки нейтрализуют противопоставление рода во множественном числе, которое само по себе является маркированной категорией. Так, прилагательные и местоимения имеют три формы в единственном числе ( например , болгарское червен , червена , червено или немецкое roter , rote , rotes ), но только одну во множественном числе (болгарское червени , немецкое rote ) [все примеры означают «красный»]. Как следствие, существительным pluralia tantum (не имеющим формы единственного числа) нельзя присвоить род. Пример с болгарским: клещи ( kleshti , «клещи»), гащи ( gashti , «штаны»), очила ( ochila , «очки»), хриле ( hrile , «жабры»). [примечание 3]

Другие языки, например, сербско-хорватский , допускают двойное обозначение форм как для числа, так и для рода. В этих языках каждое существительное имеет определенный род независимо от числа. Например, d(j)eca «дети» — это женское число единственного числа tantum , а vrata «дверь» — среднее множественное число tantum .

Местоимения могут согласовываться по роду с существительным или именной группой, к которой они относятся (их антецедент ). Иногда, однако, антецедент отсутствует — референт местоимения выводится косвенно из контекста: это встречается у личных местоимений, а также у неопределенных и фиктивных местоимений.

В случае личных местоимений род местоимения, скорее всего, будет соответствовать естественному роду референта. Действительно, в большинстве европейских языков личные местоимения имеют род; например, в английском языке ( личные местоимения he , she и it используются в зависимости от того, является ли референт мужчиной, женщиной, неодушевленным или нечеловеческим; это несмотря на то, что в английском языке, как правило, нет грамматического рода). Параллельный пример дают суффиксы объектов глаголов в арабском языке , которые соответствуют объектным местоимениям и которые также склоняются по роду во втором лице (хотя и не в первом):

Не во всех языках есть гендерные местоимения. В языках, в которых никогда не было грамматического рода, обычно есть только одно слово для «он» и «она», например, dia в малайском и индонезийском , ő в венгерском и o в турецком . В этих языках могут быть только разные местоимения и склонения в третьем лице , чтобы различать людей и неодушевленные предметы, но даже это различие часто отсутствует. (В письменном финском , например, hän используется для «он» и «она», а se для «оно», но в разговорном языке se обычно используется также для «он» и «она».)

Подробнее об этих различных типах местоимений см. Местоимение третьего лица . Проблемы могут возникнуть в языках с гендерно-специфическими местоимениями в случаях, когда пол референта неизвестен или не указан; это обсуждается в разделе Гендерно-нейтральный язык , а в отношении английского языка — в разделе Единственное число они .

В некоторых случаях род местоимения не обозначается в форме самого местоимения, но обозначается в других словах посредством согласования. Так, французское слово «я» — je , независимо от того, кто говорит; но это слово становится женским или мужским в зависимости от пола говорящего, что может быть отражено через согласование прилагательных: je suis fort e («я сильный», произносится женщиной); je suis fort (то же самое произносится мужчиной).

В языках с нулевым подлежащим (и в некоторых эллиптических выражениях в других языках) такое согласование может иметь место, даже если местоимение фактически не появляется. Например, в португальском языке :

Два предложения выше буквально означают «очень обязан»; прилагательное согласуется с естественным полом говорящего, то есть с родом местоимения первого лица, которое здесь явно не указано.

Фиктивное местоимение — это тип местоимения, используемого, когда конкретный глагольный аргумент (например, подлежащее ) отсутствует, но ссылка на аргумент тем не менее синтаксически необходима. Они встречаются в основном в языках, не поддерживающих опущение , например, в английском (потому что в языках, поддерживающих опущение, позиция аргумента может быть оставлена пустой). Примерами в английском языке являются его использование в предложениях «It's raining» и «It's nice to relax».

Если в языке есть гендерные местоимения, использование определенного слова в качестве фиктивного местоимения может включать выбор определенного рода, даже если нет существительного, с которым можно было бы согласоваться. В языках со средним родом обычно используется среднее местоимение, как в немецком es regnet («идёт дождь, идёт дождь»), где es — это среднее местоимение третьего лица единственного числа. (Английский язык ведёт себя аналогично, потому что слово it происходит от древнеанглийского среднего рода.) В языках, где есть только мужской и женский род, фиктивным местоимением может быть мужское третье лицо единственного числа, как во французском «идёт дождь»: il pleut (где il означает «он» или «оно» применительно к существительным мужского рода); хотя в некоторых языках используется женский род, как в эквивалентном валлийском предложении: mae hi'n bwrw glaw (где фиктивное местоимение hi , что означает «она» или «оно» применительно к существительным женского рода).

Аналогичное, по-видимому, произвольное назначение рода может потребоваться в случае неопределенных местоимений , когда референт, как правило, неизвестен. В этом случае вопрос обычно заключается не в том, какое местоимение использовать, а в том, к какому роду отнести данное местоимение (для таких целей, как согласование прилагательных). Например, французские местоимения quelqu'un («кто-то»), personne («никто») и quelque chose («что-то») рассматриваются как мужские — и это несмотря на то, что последние два соответствуют женским существительным ( personne означает «человек», а chose означает «вещь»). [27]

Для других ситуаций, в которых может потребоваться такое «стандартное» назначение пола, см. § Контекстное определение пола ниже.

Естественный род существительного, местоимения или именной группы — это род, к которому оно, как ожидается, будет относиться на основе соответствующих атрибутов его референта. Хотя грамматический род может совпадать с естественным родом, это не обязательно.

Обычно это означает мужской или женский род, в зависимости от пола референта. Например, в испанском языке mujer («женщина») женского рода, тогда как hombre («мужчина») мужского; эти атрибуции происходят исключительно из-за семантически присущего гендерного характера каждого существительного. [ необходима цитата ]

Грамматический род существительного не всегда совпадает с его естественным родом. Примером этого является немецкое слово Mädchen («девушка»); оно образовано от Magd («дева»), умлаутированного до Mäd- с помощью уменьшительного суффикса -chen , и этот суффикс всегда делает существительное грамматически средним. Следовательно, грамматический род Mädchen — средний, хотя его естественный род — женский (потому что оно относится к лицу женского пола).

Другие примеры включают в себя:

Обычно такие исключения составляют незначительное меньшинство.

Когда существительное с конфликтующим естественным и грамматическим родом является антецедентом местоимения, может быть неясно, какой род местоимения выбрать. Существует определенная тенденция сохранять грамматический род, когда делается близкая обратная ссылка, но переключаться на естественный род, когда ссылка находится дальше. Например, в немецком языке предложения «Девочка пришла из школы. Она сейчас делает домашнее задание» можно перевести двумя способами:

Хотя второе предложение может показаться грамматически неправильным ( constructio ad sensum ), оно часто встречается в речи. С одним или несколькими промежуточными предложениями вторая форма становится еще более вероятной. Однако переключение на естественный род никогда не возможно с артиклями и атрибутивными местоимениями или прилагательными. Таким образом, никогда не может быть правильным сказать * eine Mädchen («девочка» — с женским неопределенным артиклем) или * diese kleine Mädchen («эта маленькая девочка» — с женским указательным местоимением и прилагательным).

Это явление довольно популярно в славянских языках: например, польское kreatura (пренебрежительное «существо») женского рода, но может использоваться для обозначения как мужчины (мужской род), так и женщины (женский род), ребенка (средний род) или даже одушевленных существительных (например, собака относится к мужскому роду). Аналогично с другими пренебрежительными существительными, такими как pierdoła , ciapa , łamaga , łajza , niezdara («слабак, недотепа»); niemowa («немой») может использоваться пренебрежительно, как описано ранее, а затем может использоваться для глаголов, отмеченных как для мужского, так и для женского рода.

В случае языков, имеющих мужской и женский род, связь между биологическим полом и грамматическим родом, как правило, менее точна в случае животных, чем в случае людей. Например, в испанском языке гепард всегда un guepardo (мужской род), а зебра всегда una cebra (женский род), независимо от их биологического пола. В русском языке крыса и бабочка всегда krysa ( крыса ) и babochka ( бабочка ) (женский род). Во французском языке жираф всегда une girafe , тогда как слон всегда un éléphant . Чтобы указать пол животного, можно добавить прилагательное, как в un guepardo hembra («самка гепарда») или una cebra macho («самец зебры»). У обычных домашних или сельскохозяйственных животных чаще встречаются разные названия для самцов и самок, например , английские cow и bull , испанские vaca « корова» и toro «бык » , русские баран и овца .

Что касается местоимений, используемых для обозначения животных, они обычно согласуются по роду с существительными, обозначающими этих животных, а не с полом животных (естественный род). В таком языке, как английский, который не присваивает грамматический род существительным, местоимение, используемое для обозначения объектов ( it ), часто используется и для животных. Однако, если известен пол животного, и особенно в случае домашних животных, местоимения с родом ( he и she ) могут использоваться так же, как и для человека.

В польском языке несколько общих слов, таких как zwierzę («животное») или bydlę («животное, одна голова скота»), являются средними, но большинство названий видов — мужского или женского рода. Когда известен пол животного, его обычно называют с помощью местоимений, соответствующих его полу; в противном случае местоимения будут соответствовать роду существительного, обозначающего его вид.

Существует множество теоретических подходов к положению и структуре рода в синтаксических структурах. [28]

Существует три основных способа, с помощью которых естественные языки классифицируют существительные по родам:

В большинстве языков, имеющих грамматический род, встречается сочетание этих трех типов критериев, хотя один из них может быть более распространенным.

Во многих языках существительные приписываются к полу в значительной степени без какой-либо семантической основы, то есть не основываясь на какой-либо особенности (например, одушевленности или поле) человека или вещи, которую представляет существительное. В таких языках может быть корреляция, в большей или меньшей степени, между полом и формой существительного (например, гласной или согласной или слогом, на который оно заканчивается).

Например, в португальском и испанском языках существительные, которые оканчиваются на -o или согласную, в основном мужского рода, тогда как те, которые оканчиваются на -a , в основном женского рода, независимо от их значения. Существительным, которые оканчиваются на какую-либо другую гласную, присваивается род либо в соответствии с этимологией , по аналогии или по какой-либо другой конвенции. Эти правила могут переопределять семантику в некоторых случаях: например, существительное membro / miembro («член») всегда мужского рода, даже когда оно относится к девочке или женщине, а pessoa / persona («человек») всегда женского рода, даже когда оно относится к мальчику или мужчине, своего рода несоответствие формы и значения .

В других случаях приоритет имеет значение: существительное comunista "коммунист" является мужским родом, когда оно относится или может относиться к мужчине, даже если оно заканчивается на -a . Существительные в испанском и португальском языках, как и в других романских языках, таких как итальянский и французский, обычно следуют роду латинских слов, от которых они произошли. Когда существительные отклоняются от правил для рода, обычно есть этимологическое объяснение: problema ("проблема") является мужским родом в испанском языке, потому что оно произошло от греческого существительного среднего рода, тогда как foto ("фото") и radio ("вещательный сигнал") являются женскими, потому что они являются вырезками из fotografía и radiodifusión соответственно, оба грамматически женских существительных.

Большинство испанских существительных на -ión женского рода. Они происходят от латинских женских существительных на -ō , винительный падеж -iōnem . Обратное верно в севернокурдском языке или курманси . Например, слова endam (член) и heval (друг) могут быть мужского или женского рода в зависимости от человека, к которому они относятся.

Суффиксы часто несут определенный род. Например, в немецком языке уменьшительные с суффиксами -chen и -lein (что означает «маленький, молодой») всегда среднего рода, даже если они относятся к людям, как Mädchen («девочка») и Fräulein («молодая женщина») (см. ниже). Аналогично, суффикс -ling , который делает исчисляемые существительные из неисчисляемых существительных ( Teig «тесто» → Teigling «кусок теста»), или личные существительные из абстрактных существительных ( Lehre «обучение», Strafe «наказание» → Lehrling «ученик», Sträfling «заключенный») или прилагательных ( feige «трусливый» → Feigling «трус»), всегда производит существительные мужского рода. А немецкие суффиксы -heit и -keit (сопоставимые с -hood и -ness в английском языке) образуют существительные женского рода.

В ирландском языке существительные, оканчивающиеся на -óir / -eoir и -in, всегда относятся к мужскому роду, тогда как существительные, оканчивающиеся на -óg/-eog или -lann , всегда женского рода.

В арабском языке существительные, форма единственного числа которых оканчивается на tāʾ marbūṭah (традиционно на [ t ] , становясь [ h ] в pausa ), имеют женский род, единственными значительными исключениями являются слово خليفة khalīfah (« халиф ») и некоторые мужские личные имена ( например, أسامة ʾUsāmah ). Однако многие мужские существительные имеют «сломанную» форму множественного числа, оканчивающуюся на tāʾ marbūṭa ; например, أستاذ ustādh («мужчина-профессор») имеет множественное число أساتذة asātidha , которое можно спутать с существительным женского рода единственного числа. Пол также можно предсказать по типу происхождения : например, отглагольные существительные основы II (например, التفعيل ат-таф'ил , от فعّل، يفعّل faʿʿala, yufa''il ) всегда мужского рода.

Во французском языке существительные, оканчивающиеся на -e , как правило, женского рода, тогда как другие, как правило, мужского, но есть много исключений из этого ( например , cadre , arbre , signe , meuble , nuage являются мужскими, а façon , chanson , voix , main , eau — женского рода), обратите внимание на множество существительных мужского рода, оканчивающихся на -e , которым предшествуют двойные согласные. Некоторые суффиксы являются довольно надежными индикаторами, например, -age , который при добавлении к глаголу ( например, garer «парковать» → гараж ; nettoyer «чистить» → nettoyage «уборка») указывает на мужское существительное; однако, когда -age является частью корня слова, оно может быть женского рода, как в plage («пляж») или image . С другой стороны, существительные, оканчивающиеся на -tion , -sion и -aison, почти все являются женскими, за некоторыми исключениями, такими как cation , bastion .

Существительные иногда могут изменять свою форму, чтобы обеспечить образование родственных существительных разного пола ; например, чтобы производить существительные со схожим значением, но относящиеся к человеку другого пола. Так, в испанском языке niño означает «мальчик», а niña означает «девочка». Эту парадигму можно использовать для создания новых слов: из существительных мужского рода abogado «адвокат», diputado «член парламента» и doctor «врач» было легко образовать женские эквиваленты abogada , diputada и doctora .

Таким же образом, личные имена часто строятся с аффиксами, которые идентифицируют пол носителя. Обычные женские суффиксы, используемые в английских именах, это -a , латинского или романского происхождения ( ср. Robert и Roberta ); и -e , французского происхождения (ср. Justin и Justine ).

Хотя склонение по роду может использоваться для образования существительных и имен людей разного пола в языках, имеющих грамматический род, само по себе это не составляет грамматический род. Отдельные слова и имена для мужчин и женщин также распространены в языках, в которых вообще нет грамматической системы рода для существительных. Например, в английском языке есть женские суффиксы, такие как -ess (как в waitress ), а также различаются мужские и женские личные имена, как в приведенных выше примерах.

Имена собственные и следуют тем же правилам грамматики рода, что и нарицательные существительные. В большинстве индоевропейских языков женский грамматический род образуется с помощью окончания "a" или "e". [ необходима цитата ]

Классическая латынь обычно создавала грамматический женский род с помощью -a ( silva «лес», aqua «вода»), и это отразилось в женских именах, возникших в тот период, таких как Emilia. Романские языки сохранили эту характеристику. Например, в испанском языке приблизительно 89% существительных, которые оканчиваются на -a или -á, классифицируются как женские; то же самое относится к 98% имен с окончанием -a . [29]

В германских языках женские имена были латинизированы путем добавления -e и -a : Brunhild, Kriemhild и Hroswith стали Brunhilde, Kriemhilde и Hroswitha. Славянские женские имена: Olga (русское), Małgorzata (польское), Tetiana (украинское), Oksana (белорусское), Eliška (чешское), Bronislava (словацкое), Milica (сербское), Darina (болгарское), Lucja (хорватское), Lamija (боснийское) и Zala (словенское).

В некоторых языках существительные с человеческими отсылками имеют две формы: мужскую и женскую. Это касается не только имен собственных, но и названий профессий и национальностей. Вот некоторые примеры:

Ситуация усложняется тем, что греческий язык часто предлагает дополнительные неформальные версии этих слов. Соответствующими для английского языка являются следующие: εγγλέζος ( englezos ), Εγγλέζα ( engleza ), εγγλέζικος ( englezikos ), εγγλέζικη ( engleziki ), εγγλέζικο ( engleziko ). Формальные формы происходят от названия Αγγλία ( Anglia ) «Англия», а менее формальные — от итальянского английского .

В некоторых языках пол определяется строго семантическими критериями, но в других языках семантические критерии определяют пол лишь частично.

В некоторых языках род существительного напрямую определяется его физическими атрибутами (пол, одушевленность и т. д.), и исключений из этого правила мало или нет вообще. Таких языков сравнительно немного. Дравидийские языки используют эту систему, как описано ниже.

Другим примером является язык дизи , в котором два асимметричных рода. Женский род включает в себя всех живых существ женского пола (например, женщина, девочка, корова...) и уменьшительные ; мужской род охватывает все остальные существительные (например, мужчина, мальчик, горшок, метла...). В этом языке женские существительные всегда помечены -e или -in . [30]

В другом африканском языке, дефака , есть три рода: один для всех мужчин, один для всех женщин и третий для всех остальных существительных. Род отмечается только в личных местоимениях. Стандартные английские местоимения (см. ниже) очень похожи в этом отношении, хотя английские местоимения с указанием рода ( он , она ) используются для домашних животных, если известен пол животного, а иногда и для определенных объектов, таких как корабли, [31] например: «Что случилось с Титаником? Она (или оно) затонула».

В некоторых языках род существительных в основном может быть определен по физическим (семантическим) признакам, хотя остаются некоторые существительные, род которых не определяется таким образом (Корбетт называет это «семантическим остатком»). [32] Мировоззрение (например, мифология) носителей языка может влиять на разделение категорий. [33]

Существуют определенные ситуации, когда определение рода существительного, местоимения или именной группы может быть непростым. К ним относятся, в частности:

В языках с мужским и женским родом мужской род обычно используется по умолчанию для обозначения лиц неизвестного пола и групп людей смешанного пола. Так, во французском языке женское местоимение множественного числа elles всегда обозначает группу людей, состоящую только из женщин (или обозначает группу существительных, которые все женского рода), но мужской эквивалент ils может относиться к группе мужчин или существительных мужского рода, к смешанной группе или к группе людей неизвестного пола. В таких случаях говорят, что женский род семантически маркирован , тогда как мужской род не маркирован.

В английском языке проблема определения пола не возникает во множественном числе, поскольку пол в этом языке отражается только в местоимениях, а местоимение множественного числа they не имеет гендерных форм. Однако в единственном числе проблема часто возникает, когда речь идет о человеке неопределенного или неизвестного пола. В этом случае традиционным является единственное число they . С XVIII века предписывалось использовать мужской род ( he ), но сейчас часто предпочитают другие решения — см. Gender-neutral language .

В языках со средним родом, таких как славянские и германские языки , средний род часто используется для неопределенного указания рода, особенно когда упоминаемые вещи не являются людьми. В некоторых случаях это может применяться даже при упоминании людей, особенно детей. Например, в английском языке его можно использовать для обозначения ребенка, особенно когда говорят в общем, а не о конкретном ребенке известного пола.

В исландском языке (где сохраняется различие между мужским, женским и средним родом как в единственном, так и во множественном числе) средний род во множественном числе может использоваться для групп людей смешанного пола, когда имеются в виду конкретные люди. [36] [37] Например:

Однако при упоминании ранее не упомянутых групп людей или при упоминании людей в общем смысле, особенно при использовании неопределенного местоимения типа «some» или «all», используется мужской род множественного числа. Например:

Ниже приведен пример, противопоставляющий два способа обозначения групп, взятый из рекламы христианских общин, объявляющих о своих собраниях:

То, что мужской род в исландском языке рассматривается как наиболее общий или «немаркированный» из трех родов, также можно увидеть в том факте, что существительные для большинства профессий являются мужскими. Даже женские описания должностей, исторически заполненные женщинами, такие как hjúkrunarkona 'медсестра' и fóstra 'воспитатель детского сада' (оба на Ф. С. Г. ), были заменены мужскими, поскольку мужчины стали более представлены в этих профессиях: hjúkrunarfræðingur 'медсестра' и leikskólakennari 'воспитатель детского сада' (оба на М. С. Г ...

В шведском языке (в котором в целом действует система общего среднего рода) можно утверждать, что мужественность является ярко выраженной чертой, поскольку в слабом склонении прилагательных есть четкое окончание ( -e ) для естественно мужских существительных (например, min lill e bror , «мой младший брат»). Несмотря на это, мужское местоимение третьего лица единственного числа han обычно используется по умолчанию для человека неизвестного пола, хотя на практике неопределенное местоимение man и возвратный sig или его притяжательные формы sin/sitt/sina обычно делают это ненужным.

В польском языке , где во множественном числе проводится гендерное различие между «мужским личным» и всеми другими падежами (см. ниже), группа рассматривается как мужского рода, если в ее состав входит хотя бы один человек мужского пола.

В языках, сохраняющих трехстороннее родовое деление во множественном числе, правила определения рода (а иногда и числа) согласованной именной группы («... и ...») могут быть довольно сложными. Чешский язык является примером такого языка, с разделением (во множественном числе) на мужской род одушевленных, мужской род неодушевленных, женский и средний. Правила [38] для рода и числа согласованных групп в этом языке суммированы в разделе Чешское склонение § Род и число сложных групп .

В некоторых языках любые гендерные маркеры со временем настолько размылись (возможно, из-за дефлексии ), что их больше невозможно распознать. Например, многие немецкие существительные не указывают на свой пол ни через значение, ни через форму. В таких случаях пол существительного нужно просто запомнить, и пол можно считать неотъемлемой частью каждого существительного, если рассматривать его как запись в лексиконе говорящего . (Это отражено в словарях , которые обычно указывают пол заглавных слов существительного , где это применимо.)

Изучающим второй язык часто предлагают запомнить модификатор, обычно определенный артикль , в сочетании с каждым существительным — например, изучающий французский язык может выучить слово «стул» как la chaise (что означает «стул»); это несет информацию о том, что существительное — chaise и что оно женского рода (потому что la — это женская форма единственного числа определенного артикля).

Существительное может иметь более одного рода. [3] [6] [7] Такие сдвиги рода иногда коррелируют со сдвигами смысла, а иногда приводят к дублетам без разницы в значении. Более того, сдвиги рода иногда пересекают числовые контрасты, так что форма единственного числа существительного имеет один род, а форма множественного числа существительного имеет другой род.

Гендерный сдвиг может быть связан с различием в поле референта, как в случае с такими существительными, как comunista в испанском языке, которые могут быть как мужского, так и женского рода в зависимости от того, относится ли оно к мужчине или женщине. Он также может соответствовать некоторому другому различию в значении слова. Например, немецкое слово See , означающее «озеро», является мужским родом, тогда как идентичное слово, означающее «море», является женским. Значения норвежского существительного ting еще больше разошлись: мужской род en ting означает «вещь», тогда как средний род et ting означает «собрание». (Парламент — это Стортинг , «Великий Тинг »; другие ting , такие как Borgarting, являются региональными судами.)

Это вопрос анализа, как провести границу между одним многозначным словом с несколькими родами и набором омонимов , каждый из которых имеет один род. Например, в болгарском языке есть пара омонимов пръст ( prəst ), которые этимологически не связаны. Один из них мужского рода и означает «палец», другой — женского рода и означает «почва».

В других случаях слово может употребляться в нескольких родах безразлично. Например, в болгарском языке слово пу̀стош ( pustosh , «дикая местность») может быть как мужского рода (определенная форма пу̀стоша , pustoshə ), так и женского рода (определенная форма пустошта̀ , pustoshta ) без каких-либо изменений в значении и без каких-либо предпочтений в использовании.

В норвежском языке многие существительные могут быть как женского, так и мужского рода в зависимости от диалекта, уровня формальности или прихоти говорящего/пишущего. Даже в двух письменных формах языка есть много существительных, чей род необязателен. Выбор мужского рода часто будет казаться более формальным, чем использование женского. [ необходима цитата ] Это может быть связано с тем, что до создания норвежского нюнорска и норвежского букмола в конце 19 века норвежцы писали на датском языке, который утратил женский род, поэтому использование мужского рода (точно соответствующего датскому общему роду в спряжении в норвежском букмоле) звучит более официально для современных норвежцев. [ необходима цитата ]

Другим примером может служить слово «солнце». Его можно склонять в мужском роде: En sol, solen, soler, solene или женском: Ei sol, sola, soler, solene в норвежском букмоле . То же самое касается многих распространенных слов, таких как bok (книга), dukke (кукла), bøtte (ведро) и т. д. Многие из слов, для которых можно выбрать род, являются неодушевленными объектами, которые, как можно предположить, будут спрягаться со средним родом. Существительные, спрягаемые со средним родом, обычно не могут спрягаться как женские или мужские в норвежском языке. Также существует небольшая тенденция к использованию неопределенного артикля мужского рода даже при выборе женского спряжения существительного во многих восточнонорвежских диалектах. Например, слово «девушка» склоняется: En jente, jenta, jenter, jentene .

Иногда род существительного может меняться между формами множественного и единственного числа, как в случае с французскими словами amour («любовь»), délice («удовольствие») и orgue («орган» как музыкальный инструмент), все из которых являются мужским родом в единственном числе, но женским во множественном числе. Эти аномалии могут иметь историческое объяснение ( amour раньше также было женским в единственном числе) или быть результатом немного разных понятий ( orgue в единственном числе обычно означает шарманку , тогда как множественное число orgues обычно относится к набору колонн в церковном органе ) [ оспаривается – обсуждается ] . Другими примерами являются итальянские слова uovo («яйцо») и braccio («рука»). Они являются мужским родом в единственном числе, но образуют неправильные формы множественного числа uova и braccia , которые имеют окончания женского рода единственного числа, но имеют женское согласование множественного числа. (Это связано с формами второго склонения латинских существительных среднего рода, от которых они произошли: ovum и bracchium , с именительным падежом множественного числа ova и bracchia .) В других случаях аномалию можно объяснить формой существительного, как в шотландском гэльском . Существительные мужского рода, которые образуют множественное число путем палатализации конечной согласной, могут менять пол во множественном числе, поскольку палатализованная конечная согласная часто является маркером женского рода, например, balach beag («маленький мальчик»), но balaich bheaga («маленькие мальчики»), при этом прилагательное показывает согласование как для женского рода ( смягчение начальной согласной), так и для множественного числа (суффикс -a ).

Родственные языки не обязательно присваивают существительному один и тот же род: это показывает, что род может различаться в родственных языках. И наоборот, неродственные языки, которые находятся в контакте, могут влиять на то, как заимствованному существительному присваивается род, при этом либо заимствующий, либо донорский язык определяют род заимствованного слова.

Существительные, имеющие одинаковые значения в разных языках, не обязательно должны иметь одинаковый род. Это особенно касается вещей, не имеющих естественного рода, таких как бесполые объекты. Например, по всей видимости, в столе нет ничего, что могло бы заставить его ассоциироваться с каким-либо определенным родом, и в разных языках слова для «стола» имеют разные роды: женский, как в случае французского table ; мужской, как в случае немецкого Tisch ; или средний, как в случае норвежского bord . (Даже в пределах одного языка существительные, обозначающие одно и то же понятие, могут различаться по роду — например, из трех немецких слов для «автомобиль» Wagen мужского рода, тогда как Auto среднего рода, а Karre женского.)

Родственные существительные в близкородственных языках, скорее всего, будут иметь тот же род, потому что они, как правило, наследуют род исходного слова в родительском языке. Например, в романских языках слова для «солнца» являются мужскими, поскольку они происходят от латинского мужского рода существительного sol , тогда как слова для «луны» являются женскими, поскольку они происходят от латинского женского рода luna . (Это контрастирует с родами, встречающимися в немецком языке, где Sonne «солнце» является женским, а Mond «луна» является мужским, а также в других германских языках .) Однако из этого принципа есть исключения. Например, latte («молоко») является мужским родом в итальянском языке (как и французское lait и португальское leite ), тогда как испанское leche является женским, а румынское lapte является средним. Аналогично, слово для «лодки» является средним родом в немецком языке ( das Boot ), но является общим родом в шведском языке ( en båt ).

Ниже приведены еще несколько примеров вышеперечисленных явлений. (Они в основном взяты из славянских языков, где род во многом коррелирует с окончанием существительного.)

Заимствованные слова имеют один из двух способов определения рода:

Ибрагим выделяет несколько процессов, посредством которых язык присваивает пол вновь заимствованному слову; эти процессы следуют закономерностям, посредством которых даже дети, благодаря своему подсознательному распознаванию закономерностей, часто могут правильно предсказать пол существительного. [40]

Иногда род слова меняется со временем. Например, современное русское заимствованное слово виски ( viski ) «whisky» изначально было женского рода, [42] затем мужского, [43] а сегодня оно стало средним.

Гилад Цукерман утверждает, что кросс-лингвистическое сохранение грамматического рода может изменить не только лексику целевого языка, но и его морфологию. Например, род может косвенно влиять на производительность шаблонов существительных в том, что он называет « израильским » языком: израильский неологизм מברשת ( mivréshet , перевод: кисть ) вписывается в женский шаблон существительного mi⌂⌂é⌂et (каждый ⌂ представляет собой слот, куда вставляется радикал) из-за женского рода соответствующих слов для «кисти», таких как арабский mábrasha , идиш barsht , русский shchëtka , польское kiść ( перевод: кисть для рисования ) и szczotka , немецкое Bürste и французское brosse , все женского рода. [41] : 86

Аналогичным образом, утверждает Цукерман, израильский неологизм для слова «библиотека», ספריה ( sifriá ), соответствует женскому роду параллельных ранее существовавших европейских слов: идишский перевод yi – перевод biblioték , русский bibliotéka , польский biblioteka , немецкий Bibliothek и французский bibliothèque , а также ранее существовавшего арабского слова для слова «библиотека»: مكتبة ( máktaba , также женского рода. Результатом этого неологизма могло быть, в более общем плане, укрепление израильского יה- ( -iá ) как продуктивного женского локального суффикса (в сочетании с влиянием польского -ja и русского -ия ( -iya )). [41] : 86–87

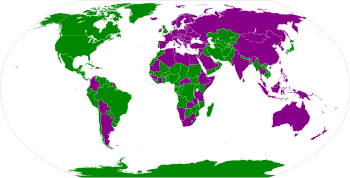

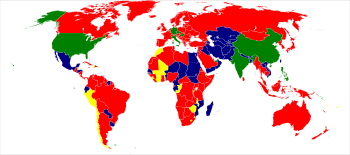

Грамматический род является распространенным явлением в языках мира. [44] Типологическое исследование 174 языков показало, что более четверти из них имеют грамматический род. [45] Системы рода редко пересекаются с системами числовых классификаторов . Системы рода и класса существительного обычно встречаются в фузионных или агглютинативных языках, тогда как классификаторы более типичны для изолирующих языков . [46] Таким образом, по словам Джоанны Николс , эти характеристики положительно коррелируют с наличием грамматического рода в языках мира: [46]

Грамматический род встречается во многих индоевропейских языках (включая испанский , французский , русский и немецкий , но не английский , бенгальский , армянский или персидский , например), афразийских языках (включая семитские и берберские языки и т. д.) и в других языковых семьях , таких как дравидийские и северо-восточно-кавказские , а также в нескольких языках австралийских аборигенов, таких как дьирбал и калау лагав я . Большинство нигеро-конголезских языков также имеют обширные системы классов существительных, которые можно сгруппировать в несколько грамматических родов.

Напротив, грамматический род обычно отсутствует в корейской , японской , тунгусской , тюркской , монгольской , австронезийской , сино-тибетской , уральской и большинстве индейских языковых семей. [47]

В современном английском языке род используется в местоимениях, которые обычно имеют естественную маркировку рода, но отсутствует система согласования рода в составе именного слова , которая является одним из центральных элементов грамматического рода в большинстве других индоевропейских языков. [48]

Во многих индоевропейских языках , за исключением английского, имеются примеры грамматического рода.

Исследования показывают, что на самых ранних стадиях протоиндоевропейского языка существовало два рода (одушевленный и неодушевленный), как и в хеттском , самом раннем засвидетельствованном индоевропейском языке. Классификация существительных на основе одушевленности и неодушевленности и отсутствие рода сегодня характерны для армянского языка . Согласно теории, одушевленный род, который (в отличие от неодушевленного) имел независимые звательные и винительные формы, позже разделился на мужской и женский, таким образом положив начало трехсторонней классификации на мужской, женский и средний. [49] [50]

Многие индоевропейские языки сохранили три рода, включая большинство славянских языков , латынь , санскрит , древнегреческий и новогреческий , немецкий , исландский , румынский и астурийский ( исключение составляют два романских языка). В них существует высокая, но не абсолютная корреляция между грамматическим родом и классом склонения . Многие лингвисты считают, что это справедливо для средней и поздней стадий праиндоевропейского языка.

Однако во многих языках число родов сократилось до двух. Некоторые языки утратили средний род, оставив только мужской и женский, как в большинстве романских языков (см. Вульгарная латынь § Утрата среднего рода . Сохранилось несколько следов среднего рода, например, особое испанское местоимение ello и итальянские существительные с так называемым «подвижным родом»), а также хиндустани и кельтские языки . Другие объединили женский и мужской род в общий род, но сохранили средний род, как в шведском и датском языках (и, в некоторой степени, в голландском ; см. Род в датском и шведском языках и Род в голландской грамматике ). Наконец, некоторые языки, такие как английский и африкаанс , почти полностью утратили грамматический род (сохранив лишь некоторые следы, например, английские местоимения he , she , they и it — африкаанс hy , sy , hulle и dit ); Армянский , бенгальский , персидский , соранский , осетинский , ория , ховарский и калашский языки полностью утратили его.

С другой стороны, можно утверждать, что в некоторых славянских языках к классическим трём родам добавились новые (см. ниже).

Хотя грамматический род был полностью продуктивной словоизменительной категорией в древнеанглийском языке , в современном английском языке система рода гораздо менее распространена, в первую очередь основана на естественном роде и отражена в основном только в местоимениях.

В современном английском языке есть несколько следов гендерной маркировки:

Однако это относительно незначительные особенности по сравнению с типичным языком с полным грамматическим родом. Английские существительные, как правило, не считаются принадлежащими к классам рода, как французские, немецкие или русские существительные. В английском языке нет согласования рода между существительными и их модификаторами ( артиклями , другими определителями или прилагательными , за редкими исключениями, такими как blonde/blonde , орфографическая конвенция, заимствованная из французского). Согласование рода фактически применяется только к местоимениям, при этом выбор местоимения определяется семантикой и/или прагматикой, а не каким-либо традиционным назначением конкретных существительных конкретным родам.

Только относительно небольшое число английских существительных имеют четкие мужские и женские формы; многие из них являются заимствованиями из негерманских языков (например, суффиксы -rix и -ress в таких словах, как aviatrix и waitress , напрямую или косвенно происходят из латыни). В английском языке нет живых продуктивных гендерных маркеров . [ требуется ссылка ] Примером такого маркера может быть суффикс -ette (французского происхождения), но сегодня он используется редко, сохраняясь в основном либо в исторических контекстах, либо с уничижительным или юмористическим умыслом.

Род английского местоимения обычно совпадает с естественным родом его референта, а не с грамматическим родом его антецедента . Выбор между she , he , they , и it сводится к тому, предназначено ли местоимение для обозначения женщины, мужчины или кого-то или чего-то еще. Однако есть определенные исключения:

Проблемы возникают при выборе личного местоимения для обозначения человека неопределенного или неизвестного пола (см. также § Контекстуальное определение пола выше). В прошлом и в некоторой степени в настоящем в английском языке мужской род использовался как «род по умолчанию». Использование множественного числа местоимения they с единственным числом является обычным на практике. Средний род it может использоваться для младенца, но обычно не для ребенка старшего возраста или взрослого. (Существуют и другие бесполые местоимения, такие как безличное местоимение one , но они, как правило, не заменяются личным местоимением.) Для получения дополнительной информации см. разделы Гендерно-нейтральный язык и Единственное число they .

Славянские языки в основном продолжают праиндоевропейскую систему трех родов: мужского, женского и среднего. Род в значительной степени коррелирует с окончаниями существительных (мужские существительные обычно оканчиваются на согласную, женские на -a , а средние на -o или -e ), но есть много исключений, особенно в случае существительных, основы которых оканчиваются на мягкую согласную . Однако некоторые языки, включая русский , чешский , словацкий и польский , также делают определенные дополнительные грамматические различия между одушевленными и неодушевленными существительными: польский язык во множественном числе и русский язык в винительном падеже различают человеческие и нечеловеческие существительные.

В русском языке различное обращение с одушевленными существительными заключается в том, что их винительный падеж (и прилагательных, их определяющих) формируется идентично родительному, а не именительному. В единственном числе это относится только к существительным мужского рода, но во множественном числе это относится ко всем родам. См. Русское склонение .

Похожая система применяется в чешском языке, но ситуация несколько иная во множественном числе: затрагиваются только существительные мужского рода, а отличительной чертой является особое флективное окончание для одушевленных существительных мужского рода в именительном падеже множественного числа, а также для прилагательных и глаголов, согласующихся с этими существительными. См. чешское склонение .

Можно сказать, что в польском языке различаются пять родов: личный мужской (относящийся к людям мужского пола), одушевленный неличный мужской род, неодушевленный мужской род, женский род и средний род. Оппозиция одушевленное-неодушевленное для мужского рода применяется в единственном числе, а личная-безличная оппозиция, которая классифицирует животных вместе с неодушевленными предметами, применяется во множественном числе. (Несколько существительных, обозначающих неодушевленные предметы, грамматически рассматриваются как одушевленные и наоборот.) Проявления различий следующие:

Некоторые существительные имеют как личные, так и безличные формы в зависимости от значения (например, klient может вести себя как безличное существительное, когда оно относится к клиенту в вычислительном смысле). Для получения дополнительной информации о вышеприведенных моделях склонения см. Польская морфология . Для некоторых правил, касающихся обращения с группами смешанного пола, см. § Контекстуальное определение пола выше.

В дравидийских языках существительные классифицируются в первую очередь на основе их семантических свойств. Самый высокий уровень классификации существительных часто описывается как находящийся между «рациональными» и «нерациональными». [52] Существительные, представляющие людей и божеств, считаются рациональными, а другие существительные (представляющие животных и предметы) рассматриваются как нерациональные. Внутри рационального класса существуют дальнейшие подразделения на мужские, женские и собирательные существительные . Для получения дополнительной информации см. Тамильскую грамматику .

В австронезийском языке вувулу-ауа звательные слова, используемые при обращении к родственнику, часто указывают пол говорящего. Например, tafi означает «сестра женщины», ʔari означает брат или сестра противоположного пола, а wane означает сестру отца женщины или дочь брата женщины. [53]