Нефтеперерабатывающий завод или нефтеперерабатывающий завод — это промышленный технологический завод , на котором нефть (сырая нефть) преобразуется и перерабатывается в такие продукты, как бензин (бензин), дизельное топливо , асфальтовая основа , мазуты , печное топливо , керосин , сжиженный нефтяной газ и нафта . [1] [2] [3] Нефтехимическое сырье, такое как этилен и пропилен, также может быть получено напрямую путем крекинга сырой нефти без необходимости использования очищенных продуктов сырой нефти, таких как нафта. [4] [5] Сырье сырой нефти обычно перерабатывается на нефтеперерабатывающем заводе . [1] Обычно на нефтеперерабатывающем заводе или рядом с ним имеется нефтебаза для хранения поступающего сырья сырой нефти, а также наливных жидких продуктов. В 2020 году общая мощность мировых нефтеперерабатывающих заводов по сырой нефти составляла около 101,2 миллиона баррелей в день. [6]

Нефтеперерабатывающие заводы, как правило, представляют собой крупные, разросшиеся промышленные комплексы с обширной системой трубопроводов, проходящих по всей территории, транспортирующих потоки жидкостей между крупными химическими перерабатывающими установками, такими как дистилляционные колонны. Во многих отношениях нефтеперерабатывающие заводы используют множество различных технологий и могут рассматриваться как типы химических заводов . С декабря 2008 года крупнейшим в мире нефтеперерабатывающим заводом является НПЗ Jamnagar , принадлежащий Reliance Industries , расположенный в Гуджарате , Индия, с перерабатывающей мощностью 1,24 миллиона баррелей (197 000 м 3 ) в день.

Нефтеперерабатывающие заводы являются неотъемлемой частью сектора переработки нефти и нефтепродуктов . [7]

Китайцы были среди первых цивилизаций, которые перерабатывали нефть. [8] Еще в первом веке китайцы перерабатывали сырую нефть для использования в качестве источника энергии. [9] [8] Между 512 и 518 годами, в конце династии Северная Вэй , китайский географ, писатель и политик Ли Даоюань представил процесс переработки нефти в различные смазочные материалы в своем знаменитом труде «Комментарий к классическому произведению о воде» . [10] [9] [8]

Сырая нефть часто перегонялась персидскими химиками , с четкими описаниями, данными в справочниках, таких как Мухаммеда ибн Закарии Рази ( ок. 865–925 ). [11] Улицы Багдада были вымощены смолой , полученной из нефти, которая стала доступной из природных месторождений в регионе. В 9 веке нефтяные месторождения эксплуатировались в районе современного Баку , Азербайджан. Эти месторождения были описаны арабским географом Абу аль-Хасаном Али аль-Масуди в 10 веке и Марко Поло в 13 веке, который описал выход этих скважин как сотни грузовых кораблей. [12] Арабские и персидские химики также перегоняли сырую нефть, чтобы производить легковоспламеняющиеся продукты для военных целей. Через исламскую Испанию перегонка стала доступна в Западной Европе к 12 веку. [13]

В эпоху династии Северная Сун (960–1127) в городе Кайфэн была основана мастерская под названием «Мастерская яростного масла» для производства очищенного масла для армии Сун в качестве оружия. Затем войска наполняли железные банки очищенным маслом и бросали их в сторону вражеских войск, вызывая пожар — фактически первую в мире « огненную бомбу ». Мастерская была одним из первых в мире заводов по переработке нефти, где тысячи людей работали над производством китайского оружия на нефтяном топливе. [14]

До девятнадцатого века нефть была известна и использовалась различными способами в Вавилоне , Египте , Китае , Филиппинах , Риме и Азербайджане . Однако современная история нефтяной промышленности, как говорят, началась в 1846 году, когда Авраам Гесснер из Новой Шотландии , Канада, разработал процесс получения керосина из угля. Вскоре после этого, в 1854 году, Игнаций Лукасевич начал производить керосин из вручную вырытых нефтяных скважин недалеко от города Кросно , Польша .

Румыния была зарегистрирована как первая страна в мировой статистике добычи нефти, согласно данным Академии мировых рекордов. [15] [16]

В Северной Америке первая нефтяная скважина была пробурена в 1858 году Джеймсом Миллером Уильямсом в Ойл-Спрингс, Онтарио , Канада. [17] В Соединенных Штатах нефтяная промышленность началась в 1859 году, когда Эдвин Дрейк нашел нефть около Титусвилля , штат Пенсильвания . [18] Промышленность медленно росла в 1800-х годах, в основном производя керосин для масляных ламп. В начале двадцатого века внедрение двигателя внутреннего сгорания и его использование в автомобилях создали рынок для бензина, который стал толчком для довольно быстрого роста нефтяной промышленности. Ранние открытия нефти, такие как в Онтарио и Пенсильвании, вскоре были вытеснены крупными нефтяными «бумами» в Оклахоме , Техасе и Калифорнии . [19]

В 1853 году Сэмюэль Кир основал первый в Америке нефтеперерабатывающий завод в Питтсбурге на Седьмой авеню недалеко от Грант-стрит. [20] Польский фармацевт и изобретатель Игнаций Лукасевич основал нефтеперерабатывающий завод в Ясло , тогда входившем в состав Австро-Венгерской империи (ныне в Польше ) в 1854 году.

Первый крупный нефтеперерабатывающий завод открылся в Плоешти, Румыния, в 1856–1857 годах. [15] Именно в Плоешти, 51 год спустя, в 1908 году, Лазэр Эделеану , румынский химик еврейского происхождения, получивший докторскую степень в 1887 году, открыв амфетамин , изобрел, запатентовал и испытал в промышленных масштабах первый современный метод жидкостной экстракции для очистки сырой нефти, процесс Эделеану . Это увеличило эффективность очистки по сравнению с чистой фракционной перегонкой и позволило широко развивать нефтеперерабатывающие заводы. Впоследствии этот процесс был внедрен во Франции, Германии, США и через несколько десятилетий получил всемирное распространение. В 1910 году Эделеану основал в Германии "Allgemeine Gesellschaft für Chemische Industrie", которая, учитывая успех названия, была переименована в Edeleanu GmbH в 1930 году. Во времена нацистов компания была куплена Deutsche Erdöl-AG, и Эделеану, будучи еврейского происхождения, вернулся в Румынию. После войны торговая марка использовалась компанией-преемницей EDELEANU Gesellschaft mbH Alzenau (RWE) для многих нефтепродуктов, в то время как компания была недавно интегрирована как EDL в Pörner Group . Нефтеперерабатывающие заводы в Плоешти, после того как были захвачены нацистской Германией , были разбомблены в ходе операции "Приливная волна" союзниками в 1943 году во время нефтяной кампании Второй мировой войны .

Еще одним близким претендентом на звание места расположения старейшего в мире нефтеперерабатывающего завода является Зальцберген в Нижней Саксонии , Германия. Зальцбергенский нефтеперерабатывающий завод был открыт в 1860 году.

В какой-то момент НПЗ в Рас-Тануре , Саудовская Аравия, принадлежащий Saudi Aramco, был объявлен крупнейшим нефтеперерабатывающим заводом в мире. На протяжении большей части 20-го века крупнейшим НПЗ был Абаданский НПЗ в Иране . Этот НПЗ сильно пострадал во время ирано-иракской войны . С 25 декабря 2008 года крупнейшим в мире нефтеперерабатывающим комплексом является Джамнагарский НПЗ, состоящий из двух расположенных бок о бок НПЗ, управляемых Reliance Industries Limited в Джамнагаре, Индия, с общей производственной мощностью 1 240 000 баррелей в день (197 000 м 3 /д). Нефтеперерабатывающий комплекс Paraguaná компании PDVSA на полуострове Парагуана , Венесуэла , мощностью 940 000 баррелей в сутки (149 000 м3 / сут) и завод Ulsan компании SK Energy в Южной Корее мощностью 840 000 баррелей в сутки (134 000 м3 / сут) являются вторым и третьим по величине соответственно.

До Второй мировой войны в начале 1940-х годов большинство нефтеперерабатывающих заводов в Соединенных Штатах состояли просто из установок перегонки сырой нефти (часто называемых установками атмосферной перегонки сырой нефти). Некоторые нефтеперерабатывающие заводы также имели установки вакуумной перегонки , а также установки термического крекинга, такие как висбрекеры (установки для снижения вязкости нефти ). Все многие другие процессы переработки, обсуждаемые ниже, были разработаны во время войны или в течение нескольких лет после войны. Они стали коммерчески доступны в течение 5-10 лет после окончания войны, и мировая нефтяная промышленность пережила очень быстрый рост. Движущей силой этого роста технологий, а также количества и размера нефтеперерабатывающих заводов по всему миру был растущий спрос на автомобильный бензин и авиационное топливо.

В Соединенных Штатах по разным сложным экономическим и политическим причинам строительство новых НПЗ фактически прекратилось примерно в 1980-х годах. Однако многие из существующих НПЗ в Соединенных Штатах модернизировали многие из своих установок и/или построили дополнительные установки с целью: увеличения мощности переработки сырой нефти, повышения октанового числа производимого ими бензина, снижения содержания серы в дизельном топливе и топливе для отопления домов для соответствия экологическим нормам и требованиям по загрязнению воздуха и воды.

В 19 веке нефтеперерабатывающие заводы в США перерабатывали сырую нефть в первую очередь для получения керосина . Не было рынка для более летучей фракции, включая бензин, который считался отходами и часто сбрасывался прямо в ближайшую реку. Изобретение автомобиля сместило спрос на бензин и дизельное топливо, которые остаются основными продуктами переработки и сегодня. [22]

Сегодня национальное и государственное законодательство требует, чтобы нефтеперерабатывающие заводы соответствовали строгим стандартам чистоты воздуха и воды. Фактически, нефтяные компании в США считают получение разрешения на строительство современного нефтеперерабатывающего завода настолько сложным и дорогостоящим, что с 1976 по 2014 год в США не было построено ни одного нового нефтеперерабатывающего завода (хотя многие были расширены), когда вступил в эксплуатацию небольшой нефтеперерабатывающий завод Dakota Prairie в Северной Дакоте. [23] Более половины нефтеперерабатывающих заводов, существовавших в 1981 году, сейчас закрыты из-за низких показателей загрузки и ускоряющихся слияний. [24] В результате этих закрытий общая мощность нефтеперерабатывающих заводов США упала в период с 1981 по 1995 год, хотя рабочая мощность оставалась довольно постоянной в этот период времени на уровне около 15 000 000 баррелей в день (2 400 000 м 3 /д). [25] Увеличение размера объектов и повышение эффективности компенсировали большую часть потерянной физической мощности отрасли. В 1982 году (самые ранние предоставленные данные) в США действовало 301 НПЗ с общей мощностью 17,9 млн баррелей (2 850 000 м 3 ) сырой нефти в день. В 2010 году в США действовало 149 НПЗ с общей мощностью 17,6 млн баррелей (2 800 000 м 3 ) в день. [26] К 2014 году количество НПЗ сократилось до 140, но общая мощность увеличилась до 18,02 млн баррелей (2 865 000 м 3 ) в день. Действительно, для того чтобы сократить эксплуатационные расходы и амортизацию, переработка осуществляется на меньшем количестве площадок, но с большей мощностью.

В 2009–2010 годах, когда потоки доходов в нефтяном бизнесе иссякли, а прибыльность нефтеперерабатывающих заводов упала из-за снижения спроса на продукцию и высоких резервов поставок, предшествовавших экономической рецессии , нефтяные компании начали закрывать или продавать менее прибыльные нефтеперерабатывающие заводы. [27]

Сырая или необработанная сырая нефть обычно не используется в промышленных целях, хотя «легкая, сладкая» (с низкой вязкостью, низким содержанием серы ) сырая нефть использовалась непосредственно в качестве топлива для горелок, чтобы производить пар для движения морских судов. Однако более легкие элементы образуют взрывоопасные пары в топливных баках и поэтому опасны, особенно на военных кораблях . Вместо этого сотни различных углеводородных молекул в сырой нефти разделяются на нефтеперерабатывающем заводе на компоненты, которые могут использоваться в качестве топлива , смазочных материалов и сырья в нефтехимических процессах, которые производят такие продукты, как пластмассы , моющие средства , растворители , эластомеры и волокна , такие как нейлон и полиэфиры .

Нефтяное ископаемое топливо сжигается в двигателях внутреннего сгорания для обеспечения энергией кораблей , автомобилей , авиационных двигателей , газонокосилок , мотоциклов и других машин. Различные температуры кипения позволяют разделять углеводороды путем перегонки . Поскольку более легкие жидкие продукты пользуются большим спросом для использования в двигателях внутреннего сгорания, современный нефтеперерабатывающий завод преобразует тяжелые углеводороды и более легкие газообразные элементы в эти более ценные продукты. [28]

Нефть может использоваться различными способами, поскольку она содержит углеводороды с различной молекулярной массой , формой и длиной, такие как парафины , ароматические соединения , нафтены (или циклоалканы ), алкены , диены и алкины . [29] В то время как молекулы в сырой нефти включают различные атомы, такие как сера и азот, углеводороды являются наиболее распространенной формой молекул, которые представляют собой молекулы различной длины и сложности, состоящие из атомов водорода и углерода , а также небольшого числа атомов кислорода. Различия в структуре этих молекул объясняют их различные физические и химические свойства , и именно это разнообразие делает сырую нефть полезной в широком диапазоне различных применений.

После отделения и очистки от любых загрязняющих веществ и примесей топливо или смазку можно продавать без дальнейшей обработки. Более мелкие молекулы, такие как изобутан и пропилен или бутилены, можно рекомбинировать для соответствия определенным требованиям к октановому числу с помощью таких процессов, как алкилирование или, что более распространено, димеризация . Октановое число бензина также можно улучшить с помощью каталитического риформинга , который включает удаление водорода из углеводородов, производя соединения с более высокими октановыми числами, такие как ароматические соединения . Промежуточные продукты, такие как газойли, можно даже перерабатывать для расщепления тяжелой длинноцепочечной нефти на более легкую короткоцепочечную с помощью различных форм крекинга , таких как каталитический крекинг в жидкой фазе , термический крекинг и гидрокрекинг . Заключительным этапом производства бензина является смешивание топлив с различными октановыми числами, давлениями паров и другими свойствами для соответствия спецификациям продукта. Другой метод переработки и модернизации этих промежуточных продуктов (остаточных масел) использует процесс удаления летучих веществ для отделения пригодной к использованию нефти от отработанного асфальтенового материала.

Нефтеперерабатывающие заводы — это крупные заводы, перерабатывающие от ста тысяч до нескольких сотен тысяч баррелей сырой нефти в день. Из-за высокой производительности многие установки работают непрерывно , в отличие от переработки партиями , в устойчивом или почти устойчивом состоянии в течение месяцев или лет. Высокая производительность также делает оптимизацию процесса и расширенный контроль процесса очень желательными.

Нефтепродукты — это материалы, полученные из сырой нефти ( нефти ) в процессе ее переработки на нефтеперерабатывающих заводах . Большая часть нефти преобразуется в нефтепродукты, которые включают несколько классов топлива. [31]

Нефтеперерабатывающие заводы также производят различные промежуточные продукты, такие как водород , легкие углеводороды, риформат и пиролизный бензин . Обычно они не транспортируются, а смешиваются или перерабатываются далее на месте. Химические заводы, таким образом, часто соседствуют с нефтеперерабатывающими заводами или в них интегрирован ряд дополнительных химических процессов. Например, легкие углеводороды подвергаются паровому крекингу на этиленовой установке, а полученный этилен полимеризуется для получения полиэтилена .

Для обеспечения как надлежащего разделения, так и защиты окружающей среды необходимо очень низкое содержание серы во всех продуктах, кроме самых тяжелых. Загрязнитель сырой серы преобразуется в сероводород посредством каталитической гидродесульфуризации и удаляется из потока продукта посредством очистки аминового газа . Используя процесс Клауса , сероводород затем преобразуется в элементарную серу для продажи в химическую промышленность. Довольно большая тепловая энергия, высвобождаемая этим процессом, напрямую используется в других частях нефтеперерабатывающего завода. Часто электростанция объединяется в весь процесс нефтепереработки для поглощения избыточного тепла.

В зависимости от состава сырой нефти и потребностей рынка, нефтеперерабатывающие заводы могут производить различные доли нефтепродуктов. Наибольшая доля нефтепродуктов используется в качестве «энергоносителей», то есть различных сортов мазута и бензина . Эти виды топлива включают или могут быть смешаны для получения бензина, реактивного топлива , дизельного топлива , печного топлива и более тяжелых мазутов. Более тяжелые (менее летучие ) фракции также могут использоваться для производства асфальта , дегтя , парафинового воска , смазочных и других тяжелых масел. Нефтеперерабатывающие заводы также производят другие химикаты , некоторые из которых используются в химических процессах для производства пластмасс и других полезных материалов. Поскольку нефть часто содержит несколько процентов серосодержащих молекул, элементарная сера также часто производится как нефтепродукт. Углерод в форме нефтяного кокса и водород также могут производиться как нефтепродукты. Полученный водород часто используется в качестве промежуточного продукта для других процессов нефтепереработки, таких как гидрокрекинг и гидродесульфурация . [32]

Нефтепродукты обычно группируются в четыре категории: легкие дистилляты (СУГ, бензин, нафта), средние дистилляты (керосин, реактивное топливо, дизельное топливо), тяжелые дистилляты и остатки (тяжелое печное топливо, смазочные масла, воск, асфальт). Для этого требуется смешивание различных видов сырья, смешивание соответствующих добавок, обеспечение краткосрочного хранения и подготовка к погрузке навалом в грузовики, баржи, продуктовые суда и железнодорожные вагоны. Эта классификация основана на способе перегонки и разделения сырой нефти на фракции. [2]

Из отходов нефти производится более 6000 наименований товаров, включая удобрения , напольные покрытия, духи , инсектициды , вазелин , мыло , витаминные капсулы. [33]

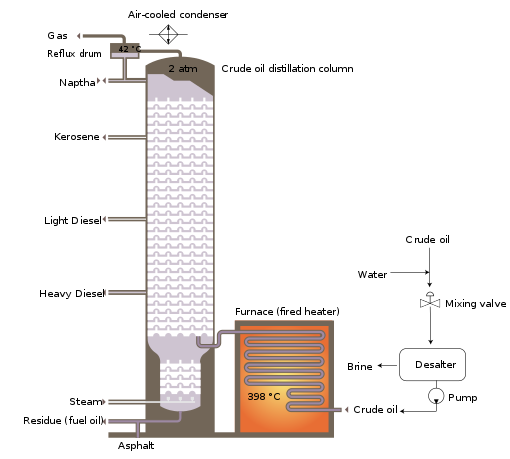

На рисунке ниже представлена схематическая диаграмма потока типичного нефтеперерабатывающего завода, которая отображает различные единичные процессы и поток промежуточных продуктов, который происходит между входящим сырым нефтяным сырьем и конечными конечными продуктами. На схеме изображена только одна из буквально сотен различных конфигураций нефтеперерабатывающего завода. На схеме также не указаны какие-либо обычные объекты нефтеперерабатывающего завода, предоставляющие коммунальные услуги, такие как пар, охлаждающая вода и электроэнергия, а также резервуары для хранения сырого нефтяного сырья, промежуточных продуктов и конечных продуктов. [1] [53] [54] [55]

Существует множество конфигураций процесса, отличных от изображенных выше. Например, установка вакуумной дистилляции может также производить фракции, которые могут быть очищены в конечные продукты, такие как веретенное масло, используемое в текстильной промышленности, легкое машинное масло, моторное масло и различные воски.

The crude oil distillation unit (CDU) is the first processing unit in virtually all petroleum refineries. The CDU distills the incoming crude oil into various fractions of different boiling ranges, each of which is then processed further in the other refinery processing units. The CDU is often referred to as the atmospheric distillation unit because it operates at slightly above atmospheric pressure.[1][2][39]Below is a schematic flow diagram of a typical crude oil distillation unit. The incoming crude oil is preheated by exchanging heat with some of the hot, distilled fractions and other streams. It is then desalted to remove inorganic salts (primarily sodium chloride).

Following the desalter, the crude oil is further heated by exchanging heat with some of the hot, distilled fractions and other streams. It is then heated in a fuel-fired furnace (fired heater) to a temperature of about 398 °C and routed into the bottom of the distillation unit.

The cooling and condensing of the distillation tower overhead is provided partially by exchanging heat with the incoming crude oil and partially by either an air-cooled or water-cooled condenser. Additional heat is removed from the distillation column by a pumparound system as shown in the diagram below.

As shown in the flow diagram, the overhead distillate fraction from the distillation column is naphtha. The fractions removed from the side of the distillation column at various points between the column top and bottom are called sidecuts. Each of the sidecuts (i.e., the kerosene, light gas oil, and heavy gas oil) is cooled by exchanging heat with the incoming crude oil. All of the fractions (i.e., the overhead naphtha, the sidecuts, and the bottom residue) are sent to intermediate storage tanks before being processed further.

A party searching for a site to construct a refinery or a chemical plant needs to consider the following issues:

Factors affecting site selection for oil refinery:

Refineries that use a large amount of steam and cooling water need to have an abundant source of water. Oil refineries, therefore, are often located nearby navigable rivers or on a seashore, nearby a port. Such location also gives access to transportation by river or by sea. The advantages of transporting crude oil by pipeline are evident, and oil companies often transport a large volume of fuel to distribution terminals by pipeline. A pipeline may not be practical for products with small output, and railcars, road tankers, and barges are used.

Petrochemical plants and solvent manufacturing (fine fractionating) plants need spaces for further processing of a large volume of refinery products, or to mix chemical additives with a product at source rather than at blending terminals.

The refining process releases a number of different chemicals into the atmosphere (see AP 42 Compilation of Air Pollutant Emission Factors) and a notable odor normally accompanies the presence of a refinery. Aside from air pollution impacts there are also wastewater concerns,[52] risks of industrial accidents such as fire and explosion, and noise health effects due to industrial noise.[56]

Many governments worldwide have mandated restrictions on contaminants that refineries release, and most refineries have installed the equipment needed to comply with the requirements of the pertinent environmental protection regulatory agencies. In the United States, there is strong pressure to prevent the development of new refineries, and no major refinery has been built in the country since Marathon's Garyville, Louisiana facility in 1976. However, many existing refineries have been expanded during that time. Environmental restrictions and pressure to prevent the construction of new refineries may have also contributed to rising fuel prices in the United States.[57] Additionally, many refineries (more than 100 since the 1980s) have closed due to obsolescence and/or merger activity within the industry itself.[58]

Environmental and safety concerns mean that oil refineries are sometimes located some distance away from major urban areas. Nevertheless, there are many instances where refinery operations are close to populated areas and pose health risks.[59][60] In California's Contra Costa County and Solano County, a shoreline necklace of refineries, built in the early 20th century before this area was populated, and associated chemical plants are adjacent to urban areas in Richmond, Martinez, Pacheco, Concord, Pittsburg, Vallejo and Benicia, with occasional accidental events that require "shelter in place" orders to the adjacent populations. A number of refineries are located in Sherwood Park, Alberta, directly adjacent to the City of Edmonton, which has a population of over 1,000,000 residents.[61]

NIOSH criteria for occupational exposure to refined petroleum solvents have been available since 1977.[62]

Modern petroleum refining involves a complicated system of interrelated chemical reactions that produce a wide variety of petroleum-based products.[63][64] Many of these reactions require precise temperature and pressure parameters.[65] The equipment and monitoring required to ensure the proper progression of these processes is complex, and has evolved through the advancement of the scientific field of petroleum engineering.[66][67]

The wide array of high pressure and/or high temperature reactions, along with the necessary chemical additives or extracted contaminants, produces an astonishing number of potential health hazards to the oil refinery worker.[68][69] Through the advancement of technical chemical and petroleum engineering, the vast majority of these processes are automated and enclosed, thus greatly reducing the potential health impact to workers.[70] However, depending on the specific process in which a worker is engaged, as well as the particular method employed by the refinery in which he/she works, significant health hazards remain.[71]

Although occupational injuries in the United States were not routinely tracked and reported at the time, reports of the health impacts of working in an oil refinery can be found as early as the 1800s. For instance, an explosion in a Chicago refinery killed 20 workers in 1890.[72] Since then, numerous fires, explosions, and other significant events have from time to time drawn the public's attention to the health of oil refinery workers.[73] Such events continue in the 21st century, with explosions reported in refineries in Wisconsin and Germany in 2018.[74]

However, there are many less visible hazards that endanger oil refinery workers.

Given the highly automated and technically advanced nature of modern petroleum refineries, nearly all processes are contained within engineering controls and represent a substantially decreased risk of exposure to workers compared to earlier times.[70] However, certain situations or work tasks may subvert these safety mechanisms, and expose workers to a number of chemical (see table above) or physical (described below) hazards.[75][76] Examples of these scenarios include:

A 2021 systematic review associated working in the petrochemical industry with increased risk of various cancers, such as mesothelioma. It also found reduced risks of other cancers, such as stomach and rectal. The systematic review did mention that several of the associations were not due to factors directly related to the petroleum industry, rather were related to lifestyle factors such as smoking. Evidence for adverse health effects for nearby residents was also weak, with the evidence primarily centering around neighborhoods in developed countries.[79]

BTX stands for benzene, toluene, xylene. This is a group of common volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that are found in the oil refinery environment, and serve as a paradigm for more in depth discussion of occupational exposure limits, chemical exposure and surveillance among refinery workers.[80][81]

The most important route of exposure for BTX chemicals is inhalation due to the low boiling point of these chemicals. The majority of the gaseous production of BTX occurs during tank cleaning and fuel transfer, which causes offgassing of these chemicals into the air.[82] Exposure can also occur through ingestion via contaminated water, but this is unlikely in an occupational setting.[83] Dermal exposure and absorption is also possible, but is again less likely in an occupational setting where appropriate personal protective equipment is in place.[83]

In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) have all established occupational exposure limits (OELs) for many of the chemicals above that workers may be exposed to in petroleum refineries.[84][85][86]

Benzene, in particular, has multiple biomarkers that can be measured to determine exposure. Benzene itself can be measured in the breath, blood, and urine, and metabolites such as phenol, t,t-muconic acid (t,tMA) and S-phenylmercapturic acid (sPMA) can be measured in urine.[91] In addition to monitoring the exposure levels via these biomarkers, employers are required by OSHA to perform regular blood tests on workers to test for early signs of some of the feared hematologic outcomes, of which the most widely recognized is leukemia. Required testing includes complete blood count with cell differentials and peripheral blood smear "on a regular basis".[92] The utility of these tests is supported by formal scientific studies.[93]

Workers are at risk of physical injuries due to a large number of high-powered machines in the relatively close proximity of the oil refinery. The high pressure required for many of the chemical reactions also presents the possibility of localized system failures resulting in blunt or penetrating trauma from exploding system components.[108]

Heat is also a hazard. The temperature required for the proper progression of certain reactions in the refining process can reach 1,600 °F (870 °C).[70] As with chemicals, the operating system is designed to safely contain this hazard without injury to the worker. However, in system failures, this is a potent threat to workers' health. Concerns include both direct injury through a heat illness or injury, as well as the potential for devastating burns should the worker come in contact with super-heated reagents/equipment.[70]

Noise is another hazard. Refineries can be very loud environments, and have previously been shown to be associated with hearing loss among workers.[109] The interior environment of an oil refinery can reach levels in excess of 90 dB.[110][56] In the United States, an average of 90 dB is the permissible exposure limit (PEL) for an 8-hour work-day.[111] Noise exposures that average greater than 85 dB over an 8-hour require a hearing conservation program to regularly evaluate workers' hearing and to promote its protection.[112] Regular evaluation of workers' auditory capacity and faithful use of properly vetted hearing protection are essential parts of such programs.[113]

While not specific to the industry, oil refinery workers may also be at risk for hazards such as vehicle-related accidents, machinery-associated injuries, work in a confined space, explosions/fires, ergonomic hazards, shift-work related sleep disorders, and falls.[114]

The theory of hierarchy of controls can be applied to petroleum refineries and their efforts to ensure worker safety.

Elimination and substitution are unlikely in petroleum refineries, as many of the raw materials, waste products, and finished products are hazardous in one form or another (e.g. flammable, carcinogenic).[94][115]

Examples of engineering controls include a fire detection/extinguishing system, pressure/chemical sensors to detect/predict loss of structural integrity,[116] and adequate maintenance of piping to prevent hydrocarbon-induced corrosion (leading to structural failure).[77][78][117][118] Other examples employed in petroleum refineries include the post-construction protection of steel components with vermiculite to improve heat/fire resistance.[119] Compartmentalization can help to prevent a fire or other systems failure from spreading to affect other areas of the structure, and may help prevent dangerous reactions by keeping different chemicals separate from one another until they can be safely combined in the proper environment.[116]

Administrative controls include careful planning and oversight of the refinery cleaning, maintenance, and turnaround processes. These occur when many of the engineering controls are shut down or suppressed and may be especially dangerous to workers. Detailed coordination is necessary to ensure that maintenance of one part of the facility will not cause dangerous exposures to those performing the maintenance, or to workers in other areas of the plant. Due to the highly flammable nature of many of the involved chemicals, smoking areas are tightly controlled and carefully placed.[75]

Personal protective equipment (PPE) may be necessary depending on the specific chemical being processed or produced. Particular care is needed during sampling of the partially-completed product, tank cleaning, and other high-risk tasks as mentioned above. Such activities may require the use of impervious outerwear, acid hood, disposable coveralls, etc.[75] More generally, all personnel in operating areas should use appropriate hearing and vision protection, avoid clothes made of flammable material (nylon, Dacron, acrylic, or blends), and full-length pants and sleeves.[75]

Worker health and safety in oil refineries is closely monitored at a national level by both the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).[120][121] In addition to federal monitoring, California's CalOSHA has been particularly active in protecting worker health in the industry, and adopted a policy in 2017 that requires petroleum refineries to perform a "Hierarchy of Hazard Controls Analysis" (see above "Hazard controls" section) for each process safety hazard.[122] Safety regulations have resulted in a below-average injury rate for refining industry workers. In a 2018 report by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, they indicate that petroleum refinery workers have a significantly lower rate of occupational injury (0.4 OSHA-recordable cases per 100 full-time workers) than all industries (3.1 cases), oil and gas extraction (0.8 cases), and petroleum manufacturing in general (1.3 cases).[123]

Below is a list of the most common regulations referenced in petroleum refinery safety citations issued by OSHA:[124]

Corrosion of metallic components is a major factor of inefficiency in the refining process. Because it leads to equipment failure, it is a primary driver for the refinery maintenance schedule. Corrosion-related direct costs in the U.S. petroleum industry as of 1996 were estimated at US$3.7 billion.[118][125]

Corrosion occurs in various forms in the refining process, such as pitting corrosion from water droplets, embrittlement from hydrogen, and stress corrosion cracking from sulfide attack.[126] From a materials standpoint, carbon steel is used for upwards of 80 percent of refinery components, which is beneficial due to its low cost. Carbon steel is resistant to the most common forms of corrosion, particularly from hydrocarbon impurities at temperatures below 205 °C, but other corrosive chemicals and environments prevent its use everywhere. Common replacement materials are low alloy steels containing chromium and molybdenum, with stainless steels containing more chromium dealing with more corrosive environments. More expensive materials commonly used are nickel, titanium, and copper alloys. These are primarily saved for the most problematic areas where extremely high temperatures and/or very corrosive chemicals are present.[127]

Corrosion is fought by a complex system of monitoring, preventative repairs, and careful use of materials. Monitoring methods include both offline checks taken during maintenance and online monitoring. Offline checks measure corrosion after it has occurred, telling the engineer when equipment must be replaced based on the historical information they have collected. This is referred to as preventative management.

Online systems are a more modern development and are revolutionizing the way corrosion is approached. There are several types of online corrosion monitoring technologies such as linear polarization resistance, electrochemical noise and electrical resistance. Online monitoring has generally had slow reporting rates in the past (minutes or hours) and been limited by process conditions and sources of error but newer technologies can report rates up to twice per minute with much higher accuracy (referred to as real-time monitoring). This allows process engineers to treat corrosion as another process variable that can be optimized in the system. Immediate responses to process changes allow the control of corrosion mechanisms, so they can be minimized while also maximizing production output.[117] In an ideal situation having on-line corrosion information that is accurate and real-time will allow conditions that cause high corrosion rates to be identified and reduced. This is known as predictive management.

Materials methods include selecting the proper material for the application. In areas of minimal corrosion, cheap materials are preferable, but when bad corrosion can occur, more expensive but longer-lasting materials should be used. Other materials methods come in the form of protective barriers between corrosive substances and the equipment metals. These can be either a lining of refractory material such as standard Portland cement or other special acid-resistant cement that is shot onto the inner surface of the vessel. Also available are thin overlays of more expensive metals that protect cheaper metal against corrosion without requiring much material.[128]