Море — это большой объём соленой воды . Существуют особые моря и море . Под морем обычно понимают Мировой океан , более обширный объём морской воды . Отдельные моря — это либо окраинные моря , либо участки второго порядка океанического моря (например, Средиземное море ), либо определённые крупные, почти замкнутые водоёмы.

Соленость водоемов сильно различается, будучи ниже у поверхности и в устьях крупных рек и выше в глубинах океана; однако относительные пропорции растворенных солей мало меняются в разных океанах. Наиболее распространенным твердым веществом, растворенным в морской воде, является хлорид натрия . Вода также содержит соли магния , кальция , калия и ртути , среди многих других элементов, некоторые в ничтожных концентрациях. Большое разнообразие организмов , включая бактерии , простейшие , водоросли , растения, грибы и животные, обитает в морях, которые предлагают широкий спектр морских местообитаний и экосистем , простирающихся по вертикали от освещенной солнцем поверхности и береговой линии до больших глубин и давлений холодной, темной абиссальной зоны , а по широте — от холодных вод под полярными ледяными шапками до теплых вод коралловых рифов в тропических регионах . Многие из основных групп организмов эволюционировали в море, и жизнь, возможно, зародилась там.

Океан смягчает климат Земли и играет важную роль в круговоротах воды , углерода и азота . Поверхность воды взаимодействует с атмосферой, обмениваясь такими свойствами, как частицы и температура, а также течениями . Поверхностные течения — это водные течения, которые создаются течениями атмосферы и ее ветрами, дующими над поверхностью воды, создавая ветровые волны , создавая посредством сопротивления медленные, но стабильные циркуляции воды, как в случае с океаном, поддерживающим глубоководные океанические течения . Глубоководные течения, известные вместе как глобальный конвейер , переносят холодную воду с полюсов в каждый океан и существенно влияют на климат Земли. Приливы , обычно дважды в день поднимающиеся и опускающиеся уровни моря , вызваны вращением Земли и гравитационным воздействием Луны и , в меньшей степени, Солнца . Приливы могут иметь очень большой диапазон в заливах или эстуариях . Подводные землетрясения, возникающие в результате движения тектонических плит под океанами, а также извержения вулканов, огромные оползни или падение крупных метеоритов могут привести к разрушительным цунами .

Моря были неотъемлемым элементом для людей на протяжении всей истории и культуры. Люди, использующие и изучающие моря, были зарегистрированы с древних времен и засвидетельствованы в доисторические времена , в то время как его современное научное изучение называется океанографией , а морское пространство регулируется морским правом , с адмиралтейским правом, регулирующим взаимодействие людей в море. Моря обеспечивают значительные запасы пищи для людей, в основном рыбы , но также моллюсков , млекопитающих и водорослей , выловленных рыбаками или выращенных под водой. Другие виды использования морей человеком включают торговлю , путешествия, добычу полезных ископаемых , производство электроэнергии , войну и такие виды отдыха, как плавание , парусный спорт и подводное плавание . Многие из этих видов деятельности загрязняют морскую среду .

Море — это взаимосвязанная система всех океанических вод Земли, включая Атлантический , Тихий , Индийский , Южный и Северный Ледовитый океаны . [1] Однако слово «море» может также использоваться для многих конкретных, гораздо меньших водоемов морской воды, таких как Северное море или Красное море . Нет четкого различия между морями и океанами , хотя, как правило, моря меньше и часто частично (как окраинные моря или, в частности, как Средиземное море ) или полностью (как внутренние моря ) окружены сушей . [2] Однако исключением из этого является Саргассово море , которое не имеет береговой линии и находится в круговом течении, Северо-Атлантическом круговороте . [3] : 90 Моря, как правило, больше озер и содержат соленую воду, но Галилейское море является пресноводным озером . [4] [a] Конвенция Организации Объединенных Наций по морскому праву гласит, что весь океан является «морем». [8] [9] [b]

Морское право в своей основе имеет определение границ океана , проясняя его применение в пограничных морях . Но то, к каким водоемам, помимо моря, применяется это право, является предметом решающих переговоров в случае Каспийского моря и его статуса как «моря», в основном вращаясь вокруг вопроса о том, является ли Каспийское море фактически океаническим морем или только соленым водоемом и, следовательно, исключительно морем в смысле общепринятого использования этого слова, как и все другие соленые озера, называемые морями. [ необходима цитата ]

Земля — единственная известная планета , на поверхности которой есть моря жидкой воды , [3] : 22 хотя на Марсе есть ледяные шапки , а на подобных планетах в других солнечных системах могут быть океаны. [11] 1 335 000 000 кубических километров (320 000 000 кубических миль) моря Земли содержат около 97,2 процента ее известной воды [12] [c] и покрывают приблизительно 71 процент ее поверхности. [3] : 7 [17] Еще 2,15% воды на Земле находится в замороженном состоянии, в морском льду, покрывающем Северный Ледовитый океан , ледяной шапке, покрывающей Антарктиду и прилегающие к ней моря , а также в различных ледниках и поверхностных отложениях по всему миру. Оставшаяся часть (около 0,65% от общего количества) образует подземные резервуары или различные стадии круговорота воды, содержащие пресную воду , встречающуюся и используемую большинством наземных форм жизни : пар в воздухе , облака, которые он медленно образует, дождь, выпадающий из них, а также озера и реки, спонтанно образующиеся по мере того, как его воды снова и снова текут в море. [12]

Научное изучение воды и круговорота воды на Земле — гидрология ; гидродинамика изучает физику воды в движении. Более позднее изучение моря, в частности, — океанография . Оно началось как изучение формы течений океана [18], но с тех пор расширилось до большой и многопрофильной области: [19] оно изучает свойства морской воды; изучает волны, приливы и течения; составляет карты береговых линий и морского дна; и изучает морскую жизнь. [20] Подотрасль, занимающаяся движением моря, его силами и силами, действующими на него, известна как физическая океанография . [21] Морская биология (биологическая океанография) изучает растения, животных и другие организмы, населяющие морские экосистемы. Оба направления опираются на химическую океанографию , которая изучает поведение элементов и молекул в океанах: в частности, в настоящее время роль океана в круговороте углерода и роль углекислого газа в растущем закислении морской воды. Морская и морская география картографирует форму и особенности моря, в то время как морская геология (геологическая океанография) предоставила доказательства дрейфа континентов , а также состава и структуры Земли , прояснила процесс седиментации и помогла в изучении вулканизма и землетрясений . [19]

Характерной чертой морской воды является ее соленость. Соленость обычно измеряется в частях на тысячу ( ‰ или промилле), и в открытом океане содержится около 35 граммов (1,2 унции) твердых веществ на литр, соленость составляет 35 ‰. В Средиземном море соленость немного выше — 38 ‰, [22] в то время как соленость северной части Красного моря может достигать 41 ‰. [23] Напротив, некоторые замкнутые гиперсоленые озера имеют гораздо более высокую соленость, например, в Мертвом море содержится 300 граммов (11 унций) растворенных твердых веществ на литр (300 ‰).

В то время как компоненты поваренной соли ( натрий и хлорид ) составляют около 85 процентов твердых веществ в растворе, есть также ионы других металлов, такие как магний и кальций , и отрицательные ионы, включая сульфат , карбонат и бромид . Несмотря на различия в уровнях солености в разных морях, относительный состав растворенных солей стабилен во всех мировых океанах. [24] [25] Морская вода слишком соленая, чтобы люди могли безопасно пить ее, так как почки не могут выделять мочу, такую же соленую, как морская вода. [26]

Хотя количество соли в океане остается относительно постоянным в масштабе миллионов лет, на соленость водоема влияют различные факторы. [27] Испарение и побочные продукты образования льда (известные как «отторжение рассола») увеличивают соленость, тогда как осадки , таяние морского льда и сток с суши уменьшают ее. [27] Например, в Балтийское море впадает много рек, и поэтому море можно считать солоноватым . [28] Между тем, Красное море очень соленое из-за высокой скорости испарения. [29]

Температура моря зависит от количества солнечной радиации, падающей на его поверхность. В тропиках, когда солнце почти над головой, температура поверхностных слоев может подняться до более чем 30 °C (86 °F), в то время как вблизи полюсов температура в равновесии с морским льдом составляет около −2 °C (28 °F). В океанах происходит непрерывная циркуляция воды. Теплые поверхностные течения охлаждаются по мере удаления от тропиков, и вода становится плотнее и тонет. Холодная вода движется обратно к экватору как глубоководное течение, движимое изменениями температуры и плотности воды, прежде чем в конечном итоге снова подняться к поверхности. Глубоководная морская вода имеет температуру от −2 °C (28 °F) до 5 °C (41 °F) во всех частях земного шара. [30]

Морская вода с типичной соленостью 35 ‰ [31] имеет точку замерзания около −1,8 °C (28,8 °F). [32] Когда ее температура становится достаточно низкой, на поверхности образуются кристаллы льда . Они распадаются на мелкие кусочки и объединяются в плоские диски, которые образуют густую суспензию, известную как снежный лед . В спокойных условиях это замерзает в тонкий плоский лист, известный как нилас , который утолщается по мере того, как новый лед образуется на его нижней стороне. В более бурных морях кристаллы снежного льда объединяются в плоские диски, известные как блины. Они скользят друг под другом и объединяются, образуя льдины . В процессе замерзания соленая вода и воздух оказываются в ловушке между ледяными кристаллами. Нилас может иметь соленость 12–15 ‰, но к тому времени, когда морскому льду исполняется один год, она падает до 4–6 ‰. [33]

Морская вода слегка щелочная и имеет средний pH около 8,2 за последние 300 миллионов лет. [34] Совсем недавно изменение климата привело к увеличению содержания углекислого газа в атмосфере; около 30–40% добавленного CO 2 поглощается океанами, образуя угольную кислоту и снижая pH (сейчас ниже 8,1 [34] ) посредством процесса, называемого закислением океана . [35] [36] [37] Степень дальнейших изменений химии океана, включая pH океана, будет зависеть от усилий по смягчению последствий изменения климата, предпринимаемых странами и их правительствами. [38]

Количество кислорода, содержащегося в морской воде, зависит в первую очередь от растений, растущих в ней. Это в основном водоросли, включая фитопланктон , а также некоторые сосудистые растения, такие как морские травы . Днем фотосинтетическая активность этих растений производит кислород, который растворяется в морской воде и используется морскими животными. Ночью фотосинтез прекращается, и количество растворенного кислорода уменьшается. В глубоком море, куда проникает недостаточно света для роста растений, растворенного кислорода очень мало. При его отсутствии органический материал разлагается анаэробными бактериями, производящими сероводород . [39]

Изменение климата , вероятно, приведет к снижению уровня кислорода в поверхностных водах, поскольку растворимость кислорода в воде падает при более высоких температурах. [40] Прогнозируется, что деоксигенация океана увеличит гипоксию на 10% и утроит субоксичные воды (концентрация кислорода на 98% ниже средней поверхностной концентрации) на каждый 1 °C потепления верхнего слоя океана. [41]

Количество света, проникающего в море, зависит от угла падения солнца, погодных условий и мутности воды. Большая часть света отражается на поверхности, а красный свет поглощается в верхних нескольких метрах. Желтый и зеленый свет достигает больших глубин, а синий и фиолетовый свет могут проникать на глубину до 1000 метров (3300 футов). Для фотосинтеза и роста растений на глубине более 200 метров (660 футов) недостаточно света. [42]

На протяжении большей части геологического времени уровень моря был выше, чем сегодня. [3] : 74 Основным фактором, влияющим на уровень моря с течением времени, являются изменения в океанической коре, при этом ожидается, что тенденция к снижению сохранится в очень долгосрочной перспективе. [43] Во время последнего ледникового максимума , около 20 000 лет назад, уровень моря был примерно на 125 метров (410 футов) ниже, чем в настоящее время (2012). [44]

По крайней мере, за последние 100 лет уровень моря повышался со средней скоростью около 1,8 миллиметра (0,071 дюйма) в год. [45] Большую часть этого повышения можно объяснить повышением температуры моря из-за изменения климата и вызванным этим небольшим тепловым расширением верхних 500 метров (1600 футов) воды. Дополнительные вклады, примерно четверть от общего объема, поступают из водных источников на суше, таких как таяние снега и ледников и извлечение грунтовых вод для орошения и других сельскохозяйственных и человеческих нужд. [46]

Ветер, дующий над поверхностью водоема, образует волны , перпендикулярные направлению ветра. Трение между воздухом и водой, вызванное легким бризом на пруду, приводит к образованию ряби . Сильный ветер над океаном вызывает более крупные волны, поскольку движущийся воздух толкает поднятые хребты воды. Волны достигают максимальной высоты, когда скорость, с которой они движутся, почти соответствует скорости ветра. В открытой воде, когда ветер дует непрерывно, как это происходит в Южном полушарии в Ревущие сороковые , длинные, организованные массы воды, называемые зыбью, катятся по океану. [3] : 83–84 [47] [48] [d] Если ветер стихает, волнообразование уменьшается, но уже сформированные волны продолжают двигаться в своем первоначальном направлении, пока не встретятся с землей. Размер волн зависит от разгона , расстояния, которое ветер прошел над водой, а также силы и продолжительности этого ветра. Когда волны встречаются с другими, приходящими с разных направлений, интерференция между ними может привести к образованию разорванных, нерегулярных волн. [47] Конструктивная интерференция может привести к появлению отдельных (неожиданных) волн-убийц, намного превышающих нормальные. [49] Большинство волн имеют высоту менее 3 м (10 футов) [49] , и не редкость, когда сильные штормы удваивают или утраивают эту высоту; [50] морские сооружения, такие как ветряные электростанции и нефтяные платформы, используют метеорологическую статистику измерений для расчета волновых сил (например, из-за столетней волны ), против которых они спроектированы. [51] Волны-убийцы, однако, были зарегистрированы на высоте более 25 метров (82 фута). [52] [53]

Вершина волны называется гребнем, самая низкая точка между волнами — впадиной, а расстояние между гребнями — длиной волны. Волна перемещается по поверхности моря ветром, но это представляет собой передачу энергии, а не горизонтальное движение воды. Когда волны приближаются к земле и движутся по мелководью , они меняют свое поведение. При приближении под углом волны могут изгибаться ( рефракция ) или огибать скалы и мысы ( дифракция ). Когда волна достигает точки, где ее самые глубокие колебания воды соприкасаются с морским дном , они начинают замедляться. Это сближает гребни и увеличивает высоту волн , что называется обмелением волн . Когда отношение высоты волны к глубине воды превышает определенный предел, она « разбивается », опрокидываясь массой пенящейся воды. [49] Она устремляется полосой вверх по пляжу, прежде чем отступить в море под действием силы тяжести. [47]

Цунами — необычная форма волны, вызванная редким мощным событием, таким как подводное землетрясение или оползень, падение метеорита, извержение вулкана или обрушение суши в море. Эти события могут временно поднять или опустить поверхность моря в пострадавшем районе, обычно на несколько футов. Потенциальная энергия вытесненной морской воды превращается в кинетическую энергию, создавая неглубокую волну, цунами, распространяющуюся наружу со скоростью, пропорциональной квадратному корню глубины воды, и которая, следовательно, распространяется намного быстрее в открытом океане, чем на континентальном шельфе. [54] В глубоком открытом море цунами имеют длину волны около 80–300 миль (от 130 до 480 км), движутся со скоростью более 600 миль в час (970 км/ч) [55] и обычно имеют высоту менее трех футов, поэтому они часто проходят незамеченными на этой стадии. [56] Напротив, волны на поверхности океана, вызванные ветрами, имеют длину в несколько сотен футов, движутся со скоростью до 65 миль в час (105 км/ч) и достигают высоты до 45 футов (14 метров). [56]

По мере того, как цунами перемещается в мелководье, его скорость уменьшается, длина волны сокращается, а амплитуда значительно увеличивается, [56] ведя себя так же, как и ветровая волна на мелководье, но в гораздо большем масштабе. Либо ложбина, либо гребень цунами могут сначала достичь побережья. [54] В первом случае море отступает и оставляет сублиторальные области вблизи берега открытыми, что является полезным предупреждением для людей на суше. [57] Когда достигает гребня, он обычно не ломается, а устремляется вглубь суши, затапливая все на своем пути. Большая часть разрушений может быть вызвана тем, что вода отступает обратно в море после того, как ударило цунами, увлекая за собой обломки и людей. Часто несколько цунами вызываются одним геологическим событием и приходят с интервалом от восьми минут до двух часов. Первая волна, достигшая берега, может быть не самой большой или самой разрушительной. [54]

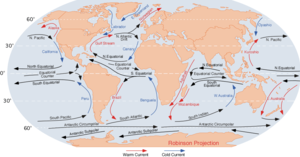

Ветер, дующий над поверхностью моря, вызывает трение на границе между воздухом и морем. Это не только вызывает образование волн, но и заставляет поверхностную морскую воду двигаться в том же направлении, что и ветер. Хотя ветры изменчивы, в любом месте они преимущественно дуют с одного направления, и таким образом может образоваться поверхностное течение. Западные ветры наиболее часты в средних широтах, в то время как восточные преобладают в тропиках. [58] Когда вода движется таким образом, другая вода втекает, чтобы заполнить пробел, и образуется круговое движение поверхностных течений, известное как круговорот . В мировых океанах есть пять основных круговоротов: два в Тихом океане, два в Атлантическом и один в Индийском океане. Другие меньшие круговороты встречаются в малых морях, а один круговорот течет вокруг Антарктиды . Эти круговороты следовали по одним и тем же маршрутам на протяжении тысячелетий, руководствуясь топографией земли, направлением ветра и эффектом Кориолиса . Поверхностные течения текут по часовой стрелке в Северном полушарии и против часовой стрелки в Южном полушарии. Вода, движущаяся от экватора, теплая, а текущая в обратном направлении, теряет большую часть своего тепла. Эти течения, как правило, смягчают климат Земли, охлаждая экваториальную область и нагревая области в более высоких широтах. [59] Глобальный климат и прогнозы погоды сильно зависят от мирового океана, поэтому глобальное моделирование климата использует модели циркуляции океана , а также модели других основных компонентов, таких как атмосфера , поверхности суши, аэрозоли и морской лед. [60] Модели океана используют раздел физики, геофизическую гидродинамику , которая описывает крупномасштабный поток жидкостей, таких как морская вода. [61]

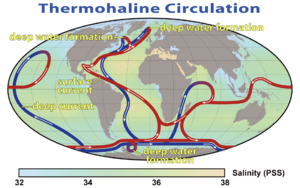

Поверхностные течения влияют только на верхние несколько сотен метров моря, но существуют также крупномасштабные потоки в глубинах океана, вызванные движением глубоководных масс. Основное глубоководное течение океана протекает через все мировые океаны и известно как термохалинная циркуляция или глобальный конвейер. Это движение медленное и обусловлено различиями в плотности воды, вызванными изменениями солености и температуры. [62] В высоких широтах вода охлаждается низкой температурой атмосферы и становится более соленой по мере кристаллизации морского льда. Оба эти фактора делают ее более плотной, и вода тонет. Из глубокого моря около Гренландии такая вода течет на юг между континентальными массивами суши по обе стороны Атлантики. Когда она достигает Антарктиды, к ней присоединяются дополнительные массы холодной, тонущей воды и течет на восток. Затем она разделяется на два потока, которые движутся на север в Индийский и Тихий океаны. Здесь она постепенно нагревается, становится менее плотной, поднимается к поверхности и замыкается сама на себя. Требуется тысяча лет, чтобы эта схема циркуляции была завершена. [59]

Помимо круговоротов, существуют временные поверхностные течения, которые возникают при определенных условиях. Когда волны встречаются с берегом под углом, создается вдольбереговое течение , поскольку вода выталкивается параллельно береговой линии. Вода закручивается на пляже под прямым углом к приближающимся волнам, но стекает прямо вниз по склону под действием силы тяжести. Чем больше разбивающиеся волны, чем длиннее пляж и чем более косой подход волны, тем сильнее вдольбереговое течение. [63] Эти течения могут перемещать большие объемы песка или гальки, создавать косы и заставлять пляжи исчезать, а водные каналы заиливаться. [59] Отбойное течение может возникнуть, когда вода скапливается у берега от наступающих волн и выбрасывается в море через канал в морском дне. Это может произойти в зазоре в песчаной отмели или около искусственного сооружения, такого как волнолом . Эти сильные течения могут иметь скорость 3 фута (0,9 м) в секунду, могут образовываться в разных местах на разных стадиях прилива и могут уносить неосторожных купальщиков. [64] Временные восходящие течения возникают, когда ветер отталкивает воду от суши, а более глубокая вода поднимается, чтобы заменить ее. Эта холодная вода часто богата питательными веществами и вызывает цветение фитопланктона и значительное увеличение продуктивности моря. [59]

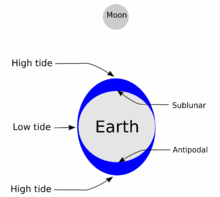

Приливы — это регулярные подъемы и падения уровня воды в морях и океанах в ответ на гравитационное воздействие Луны и Солнца, а также на эффекты вращения Земли. Во время каждого приливного цикла в любом данном месте вода поднимается до максимальной высоты, известной как «прилив», прежде чем снова отступить до минимального уровня «отлива». По мере того, как вода отступает, она обнажает все большую часть береговой полосы , также известной как приливная зона. Разница в высоте между приливом и отливом известна как приливной диапазон или приливная амплитуда. [65] [66]

В большинстве мест каждый день происходит два прилива, которые происходят с интервалом около 12 часов и 25 минут. Это половина периода в 24 часа и 50 минут, который требуется Земле, чтобы совершить полный оборот и вернуть Луну в ее предыдущее положение относительно наблюдателя. Масса Луны примерно в 27 миллионов раз меньше массы Солнца, но она в 400 раз ближе к Земле. [67] Приливная сила или сила, поднимающая приливы, быстро уменьшается с расстоянием, поэтому Луна оказывает более чем в два раза большее влияние на приливы, чем Солнце. [67] В том месте, где Земля находится ближе всего к Луне, в океане образуется выпуклость, потому что это также место, где сильнее влияние гравитации Луны. На противоположной стороне Земли лунная сила слабее всего, и это приводит к образованию другой выпуклости. Поскольку Луна вращается вокруг Земли, эти океанские выпуклости движутся вокруг Земли. Гравитационное притяжение Солнца также действует на моря, но его влияние на приливы слабее, чем влияние Луны, и когда Солнце, Луна и Земля выстраиваются в одну линию (полнолуние и новолуние), комбинированный эффект приводит к высоким «весенним приливам». Напротив, когда Солнце находится под углом 90° к Луне, если смотреть с Земли, комбинированное гравитационное воздействие на приливы слабее, вызывая низкие «квадратурные приливы». [65]

Штормовой нагон может возникнуть, когда сильный ветер нагоняет воду на мелководье у берега, и это в сочетании с системой низкого давления может привести к резкому повышению уровня моря во время прилива.

Земля состоит из магнитного центрального ядра , в основном жидкой мантии и твердой жесткой внешней оболочки (или литосферы ), которая состоит из каменистой коры Земли и более глубокого в основном твердого внешнего слоя мантии. На суше кора известна как континентальная кора , в то время как под водой она известна как океаническая кора . Последняя состоит из относительно плотного базальта и имеет толщину около пяти-десяти километров (от трех до шести миль). Относительно тонкая литосфера плавает на более слабой и горячей мантии ниже и разломана на ряд тектонических плит . [68] В середине океана магма постоянно проталкивается через морское дно между соседними плитами, образуя срединно-океанические хребты , и здесь конвекционные потоки внутри мантии имеют тенденцию раздвигать две плиты. Параллельно этим хребтам и ближе к побережьям одна океаническая плита может скользить под другую океаническую плиту в процессе, известном как субдукция . Здесь образуются глубокие впадины , и этот процесс сопровождается трением, поскольку плиты соприкасаются друг с другом. Движение происходит рывками, которые вызывают землетрясения, выделяется тепло, и магма выталкивается вверх, создавая подводные горы, некоторые из которых могут образовывать цепи вулканических островов вблизи глубоких впадин. Вблизи некоторых границ между сушей и морем немного более плотные океанические плиты скользят под континентальные плиты, и образуется больше субдукционных впадин. Когда они соприкасаются, континентальные плиты деформируются и изгибаются, вызывая горообразование и сейсмическую активность. [69] [70]

Самая глубокая впадина Земли — Марианская впадина , которая простирается примерно на 2500 километров (1600 миль) по морскому дну. Она находится недалеко от Марианских островов , вулканического архипелага в западной части Тихого океана. Ее самая глубокая точка находится на глубине 10,994 километра (почти 7 миль) под поверхностью моря. [71]

.jpg/440px-Finland_2018-07-07_(43651908284).jpg)

Зона, где суша встречается с морем, называется побережьем , а часть между самыми низкими весенними приливами и верхней границей, достигаемой плещущимися волнами, называется берегом . Пляж — это скопление песка или гальки на берегу. [72] Мыс — это точка суши, выступающая в море, а более крупный мыс называется мысом . Изгиб береговой линии, особенно между двумя мысами, называется заливом , небольшой залив с узким входом — бухтой , а большой залив можно назвать заливом . [ 73] На береговые линии влияет несколько факторов, включая силу волн, прибывающих на берег, градиент береговой границы, состав и твердость прибрежной породы, наклон прибрежного склона и изменения уровня земли из-за локального подъема или затопления. Обычно волны катятся к берегу со скоростью от шести до восьми в минуту, и они известны как конструктивные волны, поскольку они имеют тенденцию перемещать материал вверх по пляжу и оказывают незначительное эрозионное воздействие. Штормовые волны прибывают на берег в быстрой последовательности и известны как разрушительные волны, поскольку прибой перемещает пляжный материал в сторону моря. Под их воздействием песок и галька на пляже измельчаются и истираются. Во время прилива сила штормовой волны, ударяющейся о подножие скалы, имеет сокрушительный эффект, поскольку воздух в трещинах и щелях сжимается, а затем быстро расширяется с высвобождением давления. В то же время песок и галька оказывают эрозионное воздействие, поскольку они бросаются на скалы. Это имеет тенденцию подтачивать скалу, и за этим следуют обычные процессы выветривания , такие как воздействие мороза, вызывая дальнейшее разрушение. Постепенно у подножия скалы образуется волнорезная платформа, которая оказывает защитный эффект, уменьшая дальнейшую волновую эрозию. [72]

Материал, смытый с окраин суши, в конечном итоге попадает в море. Здесь он подвергается истиранию, поскольку течения, текущие параллельно побережью, размывают каналы и переносят песок и гальку от места их происхождения. Осадок, переносимый в море реками, оседает на морском дне, образуя дельты в эстуариях. Все эти материалы перемещаются вперед и назад под воздействием волн, приливов и течений. [72] Дноуглубительные работы удаляют материал и углубляют каналы, но могут иметь неожиданные последствия в других местах на побережье. Правительства прилагают усилия для предотвращения затопления суши путем строительства волнорезов , морских дамб , дамб и других морских защитных сооружений. Например, Темзский барьер предназначен для защиты Лондона от штормового нагона, [74] в то время как разрушение дамб и дамб вокруг Нового Орлеана во время урагана Катрина привело к гуманитарному кризису в Соединенных Штатах.

Море играет роль в водном или гидрологическом цикле , в котором вода испаряется из океана, проходит через атмосферу в виде пара, конденсируется , выпадает в виде дождя или снега , тем самым поддерживая жизнь на суше, и в основном возвращается в море. [75] Даже в пустыне Атакама , где выпадает мало дождей, густые облака тумана, известные как каманчака, дуют с моря и поддерживают жизнь растений. [76]

В Центральной Азии и других крупных массивах суши есть бессточные бассейны , которые не имеют выхода к морю, отделенные от океана горами или другими естественными геологическими особенностями, которые препятствуют стоку воды. Каспийское море является крупнейшим из них. Его основной приток - река Волга , оттока нет, а испарение воды делает ее соленой, поскольку накапливаются растворенные минералы. Аральское море в Казахстане и Узбекистане, а также озеро Пирамид на западе Соединенных Штатов являются еще одними примерами крупных внутренних соленых водоемов без дренажа. Некоторые бессточные озера менее соленые, но все они чувствительны к изменениям качества поступающей воды. [77]

Океаны содержат наибольшее количество активно циркулирующего углерода в мире и уступают только литосфере по количеству хранимого ими углерода. [78] Поверхностный слой океанов содержит большое количество растворенного органического углерода , который быстро обменивается с атмосферой. Концентрация растворенного неорганического углерода в глубоком слое примерно на 15 процентов выше, чем в поверхностном слое [79] , и он остается там в течение гораздо более длительных периодов времени. [80] Термохалинная циркуляция обменивает углерод между этими двумя слоями. [78]

Углерод попадает в океан, когда атмосферный углекислый газ растворяется в поверхностных слоях и превращается в угольную кислоту , карбонат и бикарбонат : [81]

Он также может проникать через реки в виде растворенного органического углерода и преобразуется фотосинтезирующими организмами в органический углерод. Он может либо обмениваться по всей пищевой цепи, либо осаждаться в более глубоких, более богатых углеродом слоях в виде мертвых мягких тканей или в раковинах и костях в виде карбоната кальция . Он циркулирует в этом слое в течение длительного времени, прежде чем либо отложится в виде осадка, либо вернется в поверхностные воды через термохалинную циркуляцию. [80]

Океаны являются домом для разнообразного набора форм жизни, которые используют его в качестве среды обитания. Поскольку солнечный свет освещает только верхние слои, большая часть океана существует в постоянной темноте. Поскольку различные глубинные и температурные зоны обеспечивают среду обитания для уникального набора видов, морская среда в целом охватывает огромное разнообразие жизни. [82] Морские среды обитания варьируются от поверхностных вод до самых глубоких океанических впадин , включая коралловые рифы, леса водорослей , луга морской травы , приливные бассейны , илистое, песчаное и каменистое морское дно и открытую пелагическую зону. Организмы, живущие в море, варьируются от китов длиной 30 метров (98 футов) до микроскопического фитопланктона и зоопланктона , грибов и бактерий. Морская жизнь играет важную роль в углеродном цикле , поскольку фотосинтезирующие организмы преобразуют растворенный углекислый газ в органический углерод, и для людей экономически важно обеспечивать рыбу для использования в качестве пищи. [83] [84] : 204–229

Жизнь могла зародиться в море, и все основные группы животных представлены там. Ученые расходятся во мнениях относительно того, где именно в море возникла жизнь: эксперименты Миллера-Юри предполагали разбавленный химический «суп» в открытой воде, но более поздние предположения включают вулканические горячие источники, мелкозернистые глинистые отложения или глубоководные « черные курильщики » — все это могло обеспечить защиту от разрушительного ультрафиолетового излучения, которое не блокировалось ранней атмосферой Земли. [3] : 138–140

Морские местообитания можно разделить горизонтально на прибрежные и открытые океанические местообитания. Прибрежные местообитания простираются от береговой линии до края континентального шельфа . Большая часть морской жизни встречается в прибрежных местообитаниях, хотя площадь шельфа занимает всего 7 процентов от общей площади океана. Открытые океанические местообитания находятся в глубоком океане за краем континентального шельфа. С другой стороны, морские местообитания можно разделить вертикально на пелагические (открытая вода), демерсальные (чуть выше морского дна) и бентические (морское дно) местообитания. Третье деление — по широте : от полярных морей с шельфовыми ледниками, морским льдом и айсбергами до умеренных и тропических вод. [3] : 150–151

Коралловые рифы, так называемые «морские тропические леса», занимают менее 0,1 процента поверхности мирового океана, однако их экосистемы включают 25 процентов всех морских видов. [85] Наиболее известны тропические коралловые рифы, такие как Большой Барьерный риф в Австралии , но холодноводные рифы являются пристанищем для широкого спектра видов, включая кораллы (только шесть из которых участвуют в формировании рифов). [3] : 204–207 [86]

Первичные морские производители – растения и микроскопические организмы в планктоне – широко распространены и очень важны для экосистемы. Было подсчитано, что половина кислорода в мире производится фитопланктоном. [87] [88] Около 45 процентов первичной продукции живого материала моря приходится на диатомовые водоросли . [89] Гораздо более крупные водоросли, обычно известные как морские водоросли , важны на местном уровне; саргассум образует плавающие дрейфы, в то время как ламинария образует леса на морском дне. [84] : 246–255 Цветковые растения в виде морских трав растут на « лугах » на песчаных отмелях, [90] мангровые заросли выстилают побережье в тропических и субтропических регионах [91], а солеустойчивые растения процветают в регулярно затапливаемых солончаках . [92] Все эти среды обитания способны поглощать большие количества углерода и поддерживать биоразнообразный ряд крупных и мелких животных. [93]

Свет может проникать только на глубину 200 метров (660 футов), поэтому это единственная часть моря, где могут расти растения. [42] Поверхностные слои часто испытывают дефицит биологически активных соединений азота. Морской азотный цикл состоит из сложных микробных преобразований, которые включают фиксацию азота , его усвоение, нитрификацию , анаммокс и денитрификацию. [94] Некоторые из этих процессов происходят в глубокой воде, поэтому там, где происходит подъем холодных вод, а также вблизи эстуариев, где присутствуют питательные вещества, поступающие с суши, рост растений выше. Это означает, что наиболее продуктивные районы, богатые планктоном и, следовательно, также рыбой, в основном прибрежные. [3] : 160–163

There is a broader spectrum of higher animal taxa in the sea than on land, many marine species have yet to be discovered and the number known to science is expanding annually.[95] Some vertebrates such as seabirds, seals and sea turtles return to the land to breed but fish, cetaceans and sea snakes have a completely aquatic lifestyle and many invertebrate phyla are entirely marine. In fact, the oceans teem with life and provide many varying microhabitats.[95] One of these is the surface film which, even though tossed about by the movement of waves, provides a rich environment and is home to bacteria, fungi, microalgae, protozoa, fish eggs and various larvae.[96]

The pelagic zone contains macro- and microfauna and myriad zooplankton which drift with the currents. Most of the smallest organisms are the larvae of fish and marine invertebrates which liberate eggs in vast numbers because the chance of any one embryo surviving to maturity is so minute.[97] The zooplankton feed on phytoplankton and on each other and form a basic part of the complex food chain that extends through variously sized fish and other nektonic organisms to large squid, sharks, porpoises, dolphins and whales.[98] Some marine creatures make large migrations, either to other regions of the ocean on a seasonal basis or vertical migrations daily, often ascending to feed at night and descending to safety by day.[99] Ships can introduce or spread invasive species through the discharge of ballast water or the transport of organisms that have accumulated as part of the fouling community on the hulls of vessels.[100]

The demersal zone supports many animals that feed on benthic organisms or seek protection from predators and the seabed provides a range of habitats on or under the surface of the substrate which are used by creatures adapted to these conditions. The tidal zone with its periodic exposure to the dehydrating air is home to barnacles, molluscs and crustaceans. The neritic zone has many organisms that need light to flourish. Here, among algal-encrusted rocks live sponges, echinoderms, polychaete worms, sea anemones and other invertebrates. Corals often contain photosynthetic symbionts and live in shallow waters where light penetrates. The extensive calcareous skeletons they extrude build up into coral reefs which are an important feature of the seabed. These provide a biodiverse habitat for reef-dwelling organisms. There is less sea life on the floor of deeper seas but marine life also flourishes around seamounts that rise from the depths, where fish and other animals congregate to spawn and feed. Close to the seabed live demersal fish that feed largely on pelagic organisms or benthic invertebrates.[101] Exploration of the deep sea by submersibles revealed a new world of creatures living on the seabed that scientists had not previously known to exist. Some like the detrivores rely on organic material falling to the ocean floor. Others cluster round deep sea hydrothermal vents where mineral-rich flows of water emerge from the seabed, supporting communities whose primary producers are sulphide-oxidising chemoautotrophic bacteria, and whose consumers include specialised bivalves, sea anemones, barnacles, crabs, worms and fish, often found nowhere else.[3]: 212 A dead whale sinking to the bottom of the ocean provides food for an assembly of organisms which similarly rely largely on the actions of sulphur-reducing bacteria. Such places support unique biomes where many new microbes and other lifeforms have been discovered.[102]

Humans have travelled the seas since they first built sea-going craft. Mesopotamians were using bitumen to caulk their reed boats and, a little later, masted sails.[103] By c. 3000 BC, Austronesians on Taiwan had begun spreading into maritime Southeast Asia.[104] Subsequently, the Austronesian "Lapita" peoples displayed great feats of navigation, reaching out from the Bismarck Archipelago to as far away as Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa.[105] Their descendants continued to travel thousands of miles between tiny islands on outrigger canoes,[106] and in the process they found many new islands, including Hawaii, Easter Island (Rapa Nui), and New Zealand.[107]

The Ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians explored the Mediterranean and Red Sea with the Egyptian Hannu reaching the Arabian Peninsula and the African Coast around 2750 BC.[108] In the first millennium BC, Phoenicians and Greeks established colonies throughout the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.[109] Around 500 BC, the Carthaginian navigator Hanno left a detailed periplus of an Atlantic journey that reached at least Senegal and possibly Mount Cameroon.[110][111] In the early Mediaeval period, the Vikings crossed the North Atlantic and even reached the northeastern fringes of North America.[112] Novgorodians had also been sailing the White Sea since the 13th century or before.[113] Meanwhile, the seas along the eastern and southern Asian coast were used by Arab and Chinese traders.[114] The Chinese Ming Dynasty had a fleet of 317 ships with 37,000 men under Zheng He in the early fifteenth century, sailing the Indian and Pacific Oceans.[3]: 12–13 In the late fifteenth century, Western European mariners started making longer voyages of exploration in search of trade. Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487 and Vasco da Gama reached India via the Cape in 1498. Christopher Columbus sailed from Cadiz in 1492, attempting to reach the eastern lands of India and Japan by the novel means of travelling westwards. He made landfall instead on an island in the Caribbean Sea and a few years later, the Venetian navigator John Cabot reached Newfoundland. The Italian Amerigo Vespucci, after whom America was named, explored the South American coastline in voyages made between 1497 and 1502, discovering the mouth of the Amazon River.[3]: 12–13 In 1519 the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan led the Spanish Magellan-Elcano expedition which would be the first to sail around the world.[3]: 12–13

As for the history of navigational instrument, a compass was first used by the ancient Greeks and Chinese to show where north lies and the direction in which the ship is heading. The latitude (an angle which ranges from 0° at the equator to 90° at the poles) was determined by measuring the angle between the Sun, Moon or a specific star and the horizon by the use of an astrolabe, Jacob's staff or sextant. The longitude (a line on the globe joining the two poles) could only be calculated with an accurate chronometer to show the exact time difference between the ship and a fixed point such as the Greenwich Meridian. In 1759, John Harrison, a clockmaker, designed such an instrument and James Cook used it in his voyages of exploration.[115] Nowadays, the Global Positioning System (GPS) using over thirty satellites enables accurate navigation worldwide.[115]

With regards to maps that are vital for navigation, in the second century, Ptolemy mapped the whole known world from the "Fortunatae Insulae", Cape Verde or Canary Islands, eastward to the Gulf of Thailand. This map was used in 1492 when Christopher Columbus set out on his voyages of discovery.[116] Subsequently, Gerardus Mercator made a practical map of the world in 1538, his map projection conveniently making rhumb lines straight.[3]: 12–13 By the eighteenth century better maps had been made and part of the objective of James Cook on his voyages was to further map the ocean. Scientific study has continued with the depth recordings of the Tuscarora, the oceanic research of the Challenger voyages (1872–1876), the work of the Scandinavian seamen Roald Amundsen and Fridtjof Nansen, the Michael Sars expedition in 1910, the German Meteor expedition of 1925, the Antarctic survey work of Discovery II in 1932, and others since.[19] Furthermore, in 1921, the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) was set up, and it constitutes the world authority on hydrographic surveying and nautical charting.[117] A fourth edition draft was published in 1986 but so far several naming disputes (such as the one over the Sea of Japan) have prevented its ratification.

Scientific oceanography began with the voyages of Captain James Cook from 1768 to 1779, describing the Pacific with unprecedented precision from 71 degrees South to 71 degrees North.[3]: 14 John Harrison's chronometers supported Cook's accurate navigation and charting on two of these voyages, permanently improving the standard attainable for subsequent work.[3]: 14 Other expeditions followed in the nineteenth century, from Russia, France, the Netherlands and the United States as well as Britain.[3]: 15 On HMS Beagle, which provided Charles Darwin with ideas and materials for his 1859 book On the Origin of Species, the ship's captain, Robert FitzRoy, charted the seas and coasts and published his four-volume report of the ship's three voyages in 1839.[3]: 15 Edward Forbes's 1854 book, Distribution of Marine Life argued that no life could exist below around 600 metres (2,000 feet). This was proven wrong by the British biologists W. B. Carpenter and C. Wyville Thomson, who in 1868 discovered life in deep water by dredging.[3]: 15 Wyville Thompson became chief scientist on the Challenger expedition of 1872–1876, which effectively created the science of oceanography.[3]: 15

On her 68,890-nautical-mile (127,580 km) journey round the globe, HMS Challenger discovered about 4,700 new marine species, and made 492 deep sea soundings, 133 bottom dredges, 151 open water trawls and 263 serial water temperature observations.[118] In the southern Atlantic in 1898/1899, Carl Chun on the Valdivia brought many new life forms to the surface from depths of over 4,000 metres (13,000 ft). The first observations of deep-sea animals in their natural environment were made in 1930 by William Beebe and Otis Barton who descended to 434 metres (1,424 ft) in the spherical steel Bathysphere.[119] This was lowered by cable but by 1960 a self-powered submersible, Trieste developed by Jacques Piccard, took Piccard and Don Walsh to the deepest part of the Earth's oceans, the Mariana Trench in the Pacific, reaching a record depth of about 10,915 metres (35,810 ft),[120] a feat not repeated until 2012 when James Cameron piloted the Deepsea Challenger to similar depths.[121] An atmospheric diving suit can be worn for deep sea operations, with a new world record being set in 2006 when a US Navy diver descended to 2,000 feet (610 m) in one of these articulated, pressurized suits.[122]

At great depths, no light penetrates through the water layers from above and the pressure is extreme. For deep sea exploration it is necessary to use specialist vehicles, either remotely operated underwater vehicles with lights and cameras or crewed submersibles. The battery-operated Mir submersibles have a three-person crew and can descend to 20,000 feet (6,100 m). They have viewing ports, 5,000-watt lights, video equipment and manipulator arms for collecting samples, placing probes or pushing the vehicle across the sea bed when the thrusters would stir up excessive sediment.[123]

Bathymetry is the mapping and study of the topography of the ocean floor. Methods used for measuring the depth of the sea include single or multibeam echosounders, laser airborne depth sounders and the calculation of depths from satellite remote sensing data. This information is used for determining the routes of undersea cables and pipelines, for choosing suitable locations for siting oil rigs and offshore wind turbines and for identifying possible new fisheries.[124]

Ongoing oceanographic research includes marine lifeforms, conservation, the marine environment, the chemistry of the ocean, the studying and modelling of climate dynamics, the air-sea boundary, weather patterns, ocean resources, renewable energy, waves and currents, and the design and development of new tools and technologies for investigating the deep.[125] Whereas in the 1960s and 1970s, research could focus on taxonomy and basic biology, in the 2010s, attention has shifted to larger topics such as climate change.[126] Researchers make use of satellite-based remote sensing for surface waters, with research ships, moored observatories and autonomous underwater vehicles to study and monitor all parts of the sea.[127]

"Freedom of the seas" is a principle in international law dating from the seventeenth century. It stresses freedom to navigate the oceans and disapproves of war fought in international waters.[128] Today, this concept is enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the third version of which came into force in 1994. Article 87(1) states: "The high seas are open to all states, whether coastal or land-locked." Article 87(1) (a) to (f) gives a non-exhaustive list of freedoms including navigation, overflight, the laying of submarine cables, building artificial islands, fishing and scientific research.[128] The safety of shipping is regulated by the International Maritime Organization. Its objectives include developing and maintaining a regulatory framework for shipping, maritime safety, environmental concerns, legal matters, technical co-operation and maritime security.[129]

UNCLOS defines various areas of water. "Internal waters" are on the landward side of a baseline and foreign vessels have no right of passage in these. "Territorial waters" extend to 12 nautical miles (22 kilometres; 14 miles) from the coastline and in these waters, the coastal state is free to set laws, regulate use and exploit any resource. A "contiguous zone" extending a further 12 nautical miles allows for hot pursuit of vessels suspected of infringing laws in four specific areas: customs, taxation, immigration and pollution. An "exclusive economic zone" extends for 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres; 230 miles) from the baseline. Within this area, the coastal nation has sole exploitation rights over all natural resources. The "continental shelf" is the natural prolongation of the land territory to the continental margin's outer edge, or 200 nautical miles from the coastal state's baseline, whichever is greater. Here the coastal nation has the exclusive right to harvest minerals and also living resources "attached" to the seabed.[128]

Control of the sea is important to the security of a maritime nation, and the naval blockade of a port can be used to cut off food and supplies in time of war. Battles have been fought on the sea for more than 3,000 years. In about 1210 B.C., Suppiluliuma II, the king of the Hittites, defeated and burned a fleet from Alashiya (modern Cyprus).[130] In the decisive 480 B.C. Battle of Salamis, the Greek general Themistocles trapped the far larger fleet of the Persian king Xerxes in a narrow channel and attacked vigorously, destroying 200 Persian ships for the loss of 40 Greek vessels.[131] At the end of the Age of Sail, the British Royal Navy, led by Horatio Nelson, broke the power of the combined French and Spanish fleets at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar.[132]

With steam and the industrial production of steel plate came greatly increased firepower in the shape of the dreadnought battleships armed with long-range guns. In 1905, the Japanese fleet decisively defeated the Russian fleet, which had travelled over 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 km), at the Battle of Tsushima.[133] Dreadnoughts fought inconclusively in the First World War at the 1916 Battle of Jutland between the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet.[134] In the Second World War, the British victory at the 1940 Battle of Taranto showed that naval air power was sufficient to overcome the largest warships,[135] foreshadowing the decisive sea-battles of the Pacific War including the Battles of the Coral Sea, Midway, the Philippine Sea, and the climactic Battle of Leyte Gulf, in all of which the dominant ships were aircraft carriers.[136][137]

Submarines became important in naval warfare in World War I, when German submarines, known as U-boats, sank nearly 5,000 Allied merchant ships,[138] including the RMS Lusitania, which helped to bring the United States into the war.[139] In World War II, almost 3,000 Allied ships were sunk by U-boats attempting to block the flow of supplies to Britain,[140] but the Allies broke the blockade in the Battle of the Atlantic, which lasted the whole length of the war, sinking 783 U-boats.[141] Since 1960, several nations have maintained fleets of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, vessels equipped to launch ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads from under the sea. Some of these are kept permanently on patrol.[142][143]

Sailing ships or packets carried mail overseas, one of the earliest being the Dutch service to Batavia in the 1670s.[144] These added passenger accommodation, but in cramped conditions. Later, scheduled services were offered but the time journeys took depended much on the weather. When steamships replaced sailing vessels, ocean-going liners took over the task of carrying people. By the beginning of the twentieth century, crossing the Atlantic took about five days and shipping companies competed to own the largest and fastest vessels. The Blue Riband was an unofficial accolade given to the fastest liner crossing the Atlantic in regular service. The Mauretania held the title with 26.06 knots (48.26 km/h) for twenty years from 1909.[145] The Hales Trophy, another award for the fastest commercial crossing of the Atlantic, was won by the United States in 1952 for a crossing that took three days, ten hours and forty minutes.[146]

The great liners were comfortable but expensive in fuel and staff. The age of the trans-Atlantic liners waned as cheap intercontinental flights became available. In 1958, a regular scheduled air service between New York and Paris taking seven hours doomed the Atlantic ferry service to oblivion. One by one the vessels were laid up, some were scrapped, others became cruise ships for the leisure industry and still others floating hotels.[147]

Maritime trade has existed for millennia. The Ptolemaic dynasty had developed trade with India using the Red Sea ports, and in the first millennium BC, the Arabs, Phoenicians, Israelites and Indians traded in luxury goods such as spices, gold, and precious stones.[148] The Phoenicians were noted sea traders and under the Greeks and Romans, commerce continued to thrive. With the collapse of the Roman Empire, European trade dwindled but it continued to flourish among the kingdoms of Africa, the Middle East, India, China and southeastern Asia.[149] From the 16th to the 19th centuries, over a period of 400 years, about 12–13 million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic to be sold as slaves in the Americas as part of the Atlantic slave trade.[150][151]: 194

Large quantities of goods are transported by sea, especially across the Atlantic and around the Pacific Rim. A major trade route passes through the Pillars of Hercules, across the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean and through the Straits of Malacca; much trade also passes through the English Channel.[152] Shipping lanes are the routes on the open sea used by cargo vessels, traditionally making use of trade winds and currents. Over 60 percent of the world's container traffic is conveyed on the top twenty trade routes.[153] Increased melting of Arctic ice since 2007 enables ships to travel the Northwest Passage for some weeks in summertime, avoiding the longer routes via the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal.[154]

Shipping is supplemented by air freight, a more expensive process mostly used for particularly valuable or perishable cargoes. Seaborne trade carries more than US$4 trillion worth of goods each year.[155] Bulk cargo in the form of liquids, powder or particles are carried loose in the holds of bulk carriers and include crude oil, grain, coal, ore, scrap metal, sand and gravel.[156] Other cargo, such as manufactured goods, is usually transported within standard-sized, lockable containers, loaded on purpose-built container ships at dedicated terminals.[157] Before the rise of containerization in the 1960s, these goods were loaded, transported and unloaded piecemeal as break-bulk cargo. Containerization greatly increased the efficiency and decreased the cost of moving goods by sea, and was a major factor leading to the rise of globalization and exponential increases in international trade in the mid-to-late 20th century.[158]

_-Deutsche_Fischfang_Union-_Cuxhaven_2008_by-RaBoe_01.jpg/440px-Kiel_(Ship_1973)_-Deutsche_Fischfang_Union-_Cuxhaven_2008_by-RaBoe_01.jpg)

Fish and other fishery products are among the most widely consumed sources of protein and other essential nutrients.[159] In 2009, 16.6% of the world's intake of animal protein and 6.5% of all protein consumed came from fish.[159] In order to fulfill this need, coastal countries have exploited marine resources in their exclusive economic zone, although fishing vessels are increasingly venturing further afield to exploit stocks in international waters.[160] In 2011, the total world production of fish, including aquaculture, was estimated to be 154 million tonnes, of which most was for human consumption.[159] The harvesting of wild fish accounted for 90.4 million tonnes, while annually increasing aquaculture contributes the rest.[159] The north west Pacific is by far the most productive area with 20.9 million tonnes (27 percent of the global marine catch) in 2010.[159] In addition, the number of fishing vessels in 2010 reached 4.36 million, whereas the number of people employed in the primary sector of fish production in the same year amounted to 54.8 million.[159]

Modern fishing vessels include fishing trawlers with a small crew, stern trawlers, purse seiners, long-line factory vessels and large factory ships which are designed to stay at sea for weeks, processing and freezing great quantities of fish. The equipment used to capture the fish may be purse seines, other seines, trawls, dredges, gillnets and long-lines and the fish species most frequently targeted are herring, cod, anchovy, tuna, flounder, mullet, squid and salmon. Overexploitation has become a serious concern; it does not only cause the depletion of fish stocks, but also substantially reduce the size of predatory fish populations.[161] It has been estimated that "industrialized fisheries typically reduced community biomass by 80% within 15 years of exploitation."[161] In order to avoid overexploitation, many countries have introduced quotas in their own waters.[162] However, recovery efforts often entail substantial costs to local economies or food provision.

.jpg/440px-Negombo4(js).jpg)

Artisan fishing methods include rod and line, harpoons, skin diving, traps, throw nets and drag nets. Traditional fishing boats are powered by paddle, wind or outboard motors and operate in near-shore waters. The Food and Agriculture Organization is encouraging the development of local fisheries to provide food security to coastal communities and help alleviate poverty.[163]

About 79 million tonnes (78M long tons; 87M short tons) of food and non-food products were produced by aquaculture in 2010, an all-time high. About six hundred species of plants and animals were cultured, some for use in seeding wild populations. The animals raised included finfish, aquatic reptiles, crustaceans, molluscs, sea cucumbers, sea urchins, sea squirts and jellyfish.[159] Integrated mariculture has the advantage that there is a readily available supply of planktonic food in the ocean, and waste is removed naturally.[164] Various methods are employed. Mesh enclosures for finfish can be suspended in the open seas, cages can be used in more sheltered waters or ponds can be refreshed with water at each high tide. Shrimps can be reared in shallow ponds connected to the open sea.[165] Ropes can be hung in water to grow algae, oysters and mussels. Oysters can be reared on trays or in mesh tubes. Sea cucumbers can be ranched on the seabed.[166] Captive breeding programmes have raised lobster larvae for release of juveniles into the wild resulting in an increased lobster harvest in Maine.[167] At least 145 species of seaweed – red, green, and brown algae – are eaten worldwide, and some have long been farmed in Japan and other Asian countries; there is great potential for additional algaculture.[168] Few maritime flowering plants are widely used for food but one example is marsh samphire which is eaten both raw and cooked.[169] A major difficulty for aquaculture is the tendency towards monoculture and the associated risk of widespread disease. Aquaculture is also associated with environmental risks; for instance, shrimp farming has caused the destruction of important mangrove forests throughout southeast Asia.[170]

Use of the sea for leisure developed in the nineteenth century, and became a significant industry in the twentieth century.[171] Maritime leisure activities are varied, and include beachgoing, cruising, yachting, powerboat racing[172] and fishing;[173] commercially organized voyages on cruise ships;[174] and trips on smaller vessels for ecotourism such as whale watching and coastal birdwatching.[175]

Sea bathing became the vogue in Europe in the 18th century after William Buchan advocated the practice for health reasons.[176] Surfing is a sport in which a wave is ridden by a surfer, with or without a surfboard. Other marine water sports include kite surfing, where a power kite propels a rider on a board across the water,[177] windsurfing, where the power is provided by a fixed, manoeuvrable sail[178] and water skiing, where a powerboat is used to pull a skier.[179]

Beneath the surface, freediving is necessarily restricted to shallow descents. Pearl divers can dive to 40 feet (12 m) with baskets to collect oysters.[180] Human eyes are not adapted for use underwater but vision can be improved by wearing a diving mask. Other useful equipment includes fins and snorkels, and scuba equipment allows underwater breathing and hence a longer time can be spent beneath the surface.[181] The depths that can be reached by divers and the length of time they can stay underwater is limited by the increase of pressure they experience as they descend and the need to prevent decompression sickness as they return to the surface. Recreational divers restrict themselves to depths of 100 feet (30 m) beyond which the danger of nitrogen narcosis increases. Deeper dives can be made with specialised equipment and training.[181]

The sea offers a very large supply of energy carried by ocean waves, tides, salinity differences, and ocean temperature differences which can be harnessed to generate electricity.[182] Forms of sustainable marine energy include tidal power, ocean thermal energy and wave power.[182][183] Electricity power stations are often located on the coast or beside an estuary so that the sea can be used as a heat sink. A colder heat sink enables more efficient power generation, which is important for expensive nuclear power plants in particular.[184]

Tidal power uses generators to produce electricity from tidal flows, sometimes by using a dam to store and then release seawater. The Rance barrage, 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) long, near St Malo in Brittany opened in 1967; it generates about 0.5 GW, but it has been followed by few similar schemes.[3]: 111–112

The large and highly variable energy of waves gives them enormous destructive capability, making affordable and reliable wave machines problematic to develop. A small 2 MW commercial wave power plant, "Osprey", was built in Northern Scotland in 1995 about 300 metres (980 feet) offshore. It was soon damaged by waves, then destroyed by a storm.[3]: 112

Offshore wind power is captured by wind turbines placed out at sea; it has the advantage that wind speeds are higher than on land, though wind farms are more costly to construct offshore.[185] The first offshore wind farm was installed in Denmark in 1991,[186] and the installed capacity of worldwide offshore wind farms reached 34 GW in 2020, mainly situated in Europe.[187]

The seabed contains large reserves of minerals which can be exploited by dredging. This has advantages over land-based mining in that equipment can be built at specialised shipyards and infrastructure costs are lower. Disadvantages include problems caused by waves and tides, the tendency for excavations to silt up and the washing away of spoil heaps. There is a risk of coastal erosion and environmental damage.[188]

Seafloor massive sulphide deposits are potential sources of silver, gold, copper, lead and zinc and trace metals since their discovery in the 1960s. They form when geothermally heated water is emitted from deep sea hydrothermal vents known as "black smokers". The ores are of high quality but prohibitively costly to extract.[189]

There are large deposits of petroleum and natural gas, in rocks beneath the seabed. Offshore platforms and drilling rigs extract the oil or gas and store it for transport to land. Offshore oil and gas production can be difficult due to the remote, harsh environment.[190] Drilling for oil in the sea has environmental impacts. Animals may be disorientated by seismic waves used to locate deposits, and there is debate as to whether this causes the beaching of whales.[191] Toxic substances such as mercury, lead and arsenic may be released. The infrastructure may cause damage, and oil may be spilt.[192]

Large quantities of methane clathrate exist on the seabed and in ocean sediment, of interest as a potential energy source.[193] Also on the seabed are manganese nodules formed of layers of iron, manganese and other hydroxides around a core. In the Pacific, these may cover up to 30 percent of the deep ocean floor. The minerals precipitate from seawater and grow very slowly. Their commercial extraction for nickel was investigated in the 1970s but abandoned in favour of more convenient sources.[194] In suitable locations, diamonds are gathered from the seafloor using suction hoses to bring gravel ashore. In deeper waters, mobile seafloor crawlers are used and the deposits are pumped to a vessel above. In Namibia, more diamonds are now collected from marine sources than by conventional methods on land.[195]

The sea holds large quantities of valuable dissolved minerals.[196] The most important, Salt for table and industrial use has been harvested by solar evaporation from shallow ponds since prehistoric times. Bromine, accumulated after being leached from the land, is economically recovered from the Dead Sea, where it occurs at 55,000 parts per million (ppm).[197]

Desalination is the technique of removing salts from seawater to leave fresh water suitable for drinking or irrigation. The two main processing methods, vacuum distillation and reverse osmosis, use large quantities of energy. Desalination is normally only undertaken where fresh water from other sources is in short supply or energy is plentiful, as in the excess heat generated by power stations. The brine produced as a by-product contains some toxic materials and is returned to the sea.[198]

Several nomadic indigenous groups in Maritime Southeast Asia live in boats and derive nearly all they need from the sea. The Moken people live on the coasts of Thailand and Burma and islands in the Andaman Sea.[199] Some Sea Gypsies are accomplished free-divers, able to descend to depths of 30 metres (98 ft), though many are adopting a more settled, land-based way of life.[200][201]

The indigenous peoples of the Arctic such as the Chukchi, Inuit, Inuvialuit and Yup'iit hunt marine mammals including seals and whales,[202] and the Torres Strait Islanders of Australia include the Great Barrier Reef among their possessions. They live a traditional life on the islands involving hunting, fishing, gardening and trading with neighbouring peoples in Papua and mainland Aboriginal Australians.[203]

The sea appears in human culture in contradictory ways, as both powerful but serene and as beautiful but dangerous.[3]: 10 It has its place in literature, art, poetry, film, theatre, classical music, mythology and dream interpretation.[204] The Ancients personified it, believing it to be under the control of a being who needed to be appeased, and symbolically, it has been perceived as a hostile environment populated by fantastic creatures; the Leviathan of the Bible,[205] Scylla in Greek mythology,[206] Isonade in Japanese mythology,[207] and the kraken of late Norse mythology.[208]

The sea and ships have been depicted in art ranging from simple drawings on the walls of huts in Lamu[204] to seascapes by Joseph Turner. In Dutch Golden Age painting, artists such as Jan Porcellis, Hendrick Dubbels, Willem van de Velde the Elder and his son, and Ludolf Bakhuizen celebrated the sea and the Dutch navy at the peak of its military prowess.[209][210] The Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai created colour prints of the moods of the sea, including The Great Wave off Kanagawa.[3]: 8

Music too has been inspired by the ocean, sometimes by composers who lived or worked near the shore and saw its many different aspects. Sea shanties, songs that were chanted by mariners to help them perform arduous tasks, have been woven into compositions and impressions in music have been created of calm waters, crashing waves and storms at sea.[211]: 4–8

As a symbol, the sea has for centuries played a role in literature, poetry and dreams. Sometimes it is there just as a gentle background but often it introduces such themes as storm, shipwreck, battle, hardship, disaster, the dashing of hopes and death.[211]: 45 In his epic poem the Odyssey, written in the eighth century BC,[212] Homer describes the ten-year voyage of the Greek hero Odysseus who struggles to return home across the sea's many hazards after the war described in the Iliad.[213] The sea is a recurring theme in the Haiku poems of the Japanese Edo period poet Matsuo Bashō (松尾 芭蕉) (1644–1694).[214] In the works of psychiatrist Carl Jung, the sea symbolizes the personal and the collective unconscious in dream interpretation, the depths of the sea symbolizing the depths of the unconscious mind.[215]

The environmental issues that affect the sea can loosely be grouped into those that stem from marine pollution, from over exploitation and those that stem from climate change. They all impact marine ecosystems and food webs and may result in consequences as yet unrecognised for the biodiversity and continuation of marine life forms.[216] An overview of environmental issues is shown below:

Many substances enter the sea as a result of human activities. Combustion products are transported in the air and deposited into the sea by precipitation. Industrial outflows and sewage contribute heavy metals, pesticides, PCBs, disinfectants, household cleaning products and other synthetic chemicals. These become concentrated in the surface film and in marine sediment, especially estuarine mud. The result of all this contamination is largely unknown because of the large number of substances involved and the lack of information on their biological effects.[219] The heavy metals of greatest concern are copper, lead, mercury, cadmium and zinc which may be bio-accumulated by marine organisms and are passed up the food chain.[220]

Much floating plastic rubbish does not biodegrade, instead disintegrating over time and eventually breaking down to the molecular level. Rigid plastics may float for years.[221] In the centre of the Pacific gyre there is a permanent floating accumulation of mostly plastic waste[222] and there is a similar garbage patch in the Atlantic.[223] Foraging sea birds such as the albatross and petrel may mistake debris for food, and accumulate indigestible plastic in their digestive systems. Turtles and whales have been found with plastic bags and fishing line in their stomachs. Microplastics may sink, threatening filter feeders on the seabed.[224]

Most oil pollution in the sea comes from cities and industry.[225] Oil is dangerous for marine animals. It can clog the feathers of sea birds, reducing their insulating effect and the birds' buoyancy, and be ingested when they preen themselves in an attempt to remove the contaminant. Marine mammals are less seriously affected but may be chilled through the removal of their insulation, blinded, dehydrated or poisoned. Benthic invertebrates are swamped when the oil sinks, fish are poisoned and the food chain is disrupted. In the short term, oil spills result in wildlife populations being decreased and unbalanced, leisure activities being affected and the livelihoods of people dependent on the sea being devastated.[226] The marine environment has self-cleansing properties and naturally occurring bacteria will act over time to remove oil from the sea. In the Gulf of Mexico, where oil-eating bacteria are already present, they take only a few days to consume spilt oil.[227]

Run-off of fertilisers from agricultural land is a major source of pollution in some areas and the discharge of raw sewage has a similar effect. The extra nutrients provided by these sources can cause excessive plant growth. Nitrogen is often the limiting factor in marine systems, and with added nitrogen, algal blooms and red tides can lower the oxygen level of the water and kill marine animals. Such events have created dead zones in the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Mexico.[225] Some algal blooms are caused by cyanobacteria that make shellfish that filter feed on them toxic, harming animals like sea otters.[228] Nuclear facilities too can pollute. The Irish Sea was contaminated by radioactive caesium-137 from the former Sellafield nuclear fuel processing plant[229] and nuclear accidents may also cause radioactive material to seep into the sea, as did the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in 2011.[230]

The dumping of waste (including oil, noxious liquids, sewage and garbage) at sea is governed by international law. The London Convention (1972) is a United Nations agreement to control ocean dumping which had been ratified by 89 countries by 8 June 2012.[231] MARPOL 73/78 is a convention to minimize pollution of the seas by ships. By May 2013, 152 maritime nations had ratified MARPOL.[232]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)The naval battle of Tsushima, the ultimate contest of the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War, was one of the most decisive sea battles in history.

{{cite book}}: |work= ignored (help){{cite book}}: |work= ignored (help)