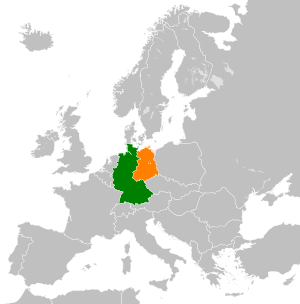

Воссоединение Германии (нем. Deutsche Wiedervereinigung ) — процесс восстановления Германии как единого полноправного суверенного государства , который состоялся в период с 9 ноября 1989 г. по 15 марта 1991 г. «Договор об объединении» вступил в силу 3 октября 1990 г., распустив Германию. Германская Демократическая Республика (ГДР; немецкий: Deutsche Demokratische Republik , DDR или Восточная Германия) и интеграция недавно восстановленных составных федеративных земель в Федеративную Республику Германия (ФРГ; немецкий: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD или Западная Германия) с образованием нынешняя Германия . Эта дата была выбрана в качестве традиционного Дня немецкого единства ( Tag der deutschen Einheit ), и с тех пор она ежегодно отмечается как национальный праздник в Германии, начиная с 1991 года. [1] В рамках воссоединения Восточный и Западный Берлин также были де фактически объединились в единый город, который со временем стал столицей Германии.

Правительство Восточной Германии, в котором доминировала Социалистическая единая партия Германии (СЕПГ) ( коммунистическая партия ), начало давать сбои 2 мая 1989 года, когда снос пограничного забора Венгрии с Австрией открыл дыру в железном занавесе . Граница по-прежнему тщательно охранялась, но Панъевропейский пикник и нерешительная реакция правителей Восточного блока привели в движение необратимое движение. [2] [3] Это привело к исходу тысяч восточных немцев, бежавших в Западную Германию через Венгрию . Мирная революция , часть международных революций 1989 года , включающая серию протестов граждан Восточной Германии, привела к падению Берлинской стены 9 ноября 1989 года и первым свободным выборам в ГДР позднее, 18 марта 1990 года, а затем к переговорам. между двумя странами, кульминацией которого стал Договор об объединении. [1] Другие переговоры между двумя Германиями и четырьмя оккупационными державами в Германии привели к так называемому «Договору двух плюс четырех» ( Договору об окончательном урегулировании в отношении Германии ), предоставляющему 15 марта 1991 года полный суверенитет объединенной Германии. Государство, две части которого ранее были связаны рядом ограничений, вытекающих из их статуса оккупационных зон после Второй мировой войны , однако только 31 августа 1994 года последние российские оккупационные войска покинули Германию.

После окончания Второй мировой войны в Европе старый Германский Рейх был упразднен, а Германия была разделена на четыре страны-союзницы. Никакого мирного договора не было. Возникли две страны. Американская, британская и французская зоны объединились 23 мая 1949 года в ФРГ, то есть Западную Германию. ГДР, то есть Восточная Германия, была создана в октябре 1949 года. Западногерманское государство вступило в НАТО в 1955 году. В 1990 году ряд продолжали сохраняться мнения относительно того, можно ли сказать, что воссоединенная Германия представляет «Германию в целом» [b] для этой цели. В контексте успешных международных революций 1989 года против коммунистических государств, включая ГДР; 12 сентября 1990 года в соответствии с договором «два плюс четыре» с четырьмя союзниками как Восточная, так и Западная Германия обязались соблюдать принцип, согласно которому их совместная граница до 1990 года составляла всю территорию, на которую могло претендовать правительство Германии, и, следовательно, не было никаких других земель за пределами этой границы, которые были бы оккупированы частями Германии в целом . Восточная Германия восстановила федеративные земли на своей территории и впоследствии распалась 3 октября 1990 года ; Также в тот же день образовалась современная Германия , когда новые государства присоединились к ФРГ, а Восточный и Западный Берлин были объединены в один город.

Воссоединенное государство является не государством-преемником , а расширенным продолжением западногерманского государства 1949–1990 годов. Расширенная Федеративная Республика Германия сохранила места Западной Германии в руководящих органах Европейского экономического сообщества (ЕС) (позже Европейский Союз / ЕС) и в международных организациях, включая Организацию Североатлантического договора (НАТО) и Организацию Объединенных Наций (ООН). ), при этом отказавшись от членства в Варшавском договоре (WP) и других международных организациях, к которым принадлежала Восточная Германия.

Термин «воссоединение Германии» был присвоен процессу присоединения Германской Демократической Республики к Федеративной Республике Германия с полным немецким суверенитетом из четырех оккупированных союзниками стран, чтобы отличить его от процесса объединения большинства немецких государств в Германскую Германию. Империя (Германский рейх) во главе с Королевством Пруссия , проходившая с 18 августа 1866 года по 18 января 1871 года, 3 октября 1990 года стала днем, когда Германия вновь стала единым национальным государством . Однако по политическим и дипломатическим причинам западногерманские политики тщательно избегали термина « воссоединение » во время подготовки к тому, что немцы часто называют Die Wende (примерно: «поворотный момент»). В договоре 1990 года официальный термин определяется как Deutsche Einheit («германское единство»); [1] это обычно используется в Германии.

После 1990 года термин die Wende стал более распространенным. Этот термин обычно относится к событиям (в основном в Восточной Европе), которые привели к фактическому воссоединению, и в широком смысле переводится как «поворотный момент». Антикоммунистические активисты из Восточной Германии отвергли термин «венде» , предложенный генеральным секретарем СЕПГ Эгоном Кренцем . [4]

Некоторые заявляли, что воссоединение можно квалифицировать как аннексию ГДР ФРГ. [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] Ученый Нед Ричардсон-Литтл из Эрфуртского университета отметил, что терминологию аннексии можно интерпретировать с учетом опыта любого политического спектра. [12] В 2015 году Россия предложила классифицировать это как аннексию. Михаил Горбачев назвал это «бредом». [13] [14] В 2010 году Маттиас Платцек назвал воссоединение « аншлюсом ». [15]

5 июня 1945 года Берлинской декларацией было подтверждено поражение нацистской Германии / Германского рейха во Второй мировой войне , германский рейх был упразднен де-юре , а Германия была оккупирована четырьмя странами, представляющими победивших союзников , подписавших соглашение (США). , Великобритания, Франция и СССР), декларация также сформировала Союзный контрольный совет (ACC) этих 4 стран, управляющих Германией [16] [17] и подтвердила границы Германии до того, как она получила Австрию . В соответствии с Потсдамским соглашением на Потсдамской конференции между тремя основными союзниками, нанесшими поражение европейской оси (США, Великобритания и СССР) 2 августа 1945 года, Германия была разделена союзниками на оккупационные зоны, каждая из которых находилась под военным правительством либо Соединенных Штатов, либо СССР. Штаты (США), Великобритания (Великобритания), Франция или Советский Союз (СССР). Соглашение также изменило границу Германии: страна де-факто потеряла свои территории к востоку от линии Одер-Нейсе Польше и Советскому Союзу (большая часть для Польши, потому что восточные территории бывшей Польши были аннексированы СССР). Решение Германии о границе было принято под давлением диктатора Советского Союза Сталина. Во время и после войны многие этнические немцы, проживавшие на традиционно немецких землях в Центральной и Восточной Европе , включая территории к востоку от линии Одер-Нейсе, бежали и были изгнаны на послевоенную территорию Германии и Австрии. Саар, территория французской оккупационной зоны , была отделена от Германии, когда 17 декабря 1947 года вступила в силу ее собственная конституция, ставшая французским протекторатом. [18]

Среди союзников геополитическая напряженность между Советским Союзом и западными союзниками в оккупированной Германии как часть их напряженности в мире привела к тому, что Советы де-факто вышли из АКК 20 марта 1948 года (четыре страны-оккупанта восстановили действие АКК). в 1971 г.) и блокировал Западный Берлин (после введения новой валюты в Западной Германии 20 июня того же года) с 20 июня 1948 г. по 12 мая 1949 г., хотя позже СССР не смог заставить трех западных союзников уйти из Западного Берлина, поскольку они хотели; следовательно, основание нового немецкого государства стало невозможным. Федеративная Республика Германия или «Западная Германия», либеральная демократия , была создана в зонах США , Великобритании и Франции 23 мая 1949 года. Западная Германия была де-юре создана в Тризоне , оккупированной тремя западными союзниками, и основана 1 августа. 1948 г., ее предшественником была Бизона , образованная зонами США и Великобритании 1 января 1947 г. до участия французской зоны, [19] [20] [21] Тризона не включала Западный Берлин, который также был оккупирован тремя западными союзниками. хотя город де-факто был частью западногерманского государства; Германская Демократическая Республика или «Восточная Германия», коммунистическое государство с плановой и государственной экономикой , объявившее себя не преемником Германского Рейха, бывшим юридическим немецким государством, была создана в советской зоне 7 октября 1949 года, это де-юре не включал Восточный Берлин, оккупированный Советами, хотя город был де-факто его столицей: острому идеологическому конфликту между немецкими политиками и социологами в их самоуправляющемся обществе Восток-Запад предшествовало влияние высших иностранных оккупантов, однако на самом деле это только стал официальным с рождением двух стран Германии в контексте международной напряженности периода холодной войны . Столица Западной Германии находилась в Бонне ; однако он считался лишь временным из-за того, что западногерманская цель - Берлин, который был разделен с восточной частью , де-факто управляемой Восточной Германией. Восточная Германия изначально также хотела получить Западный Берлин и сделать объединенный Берлин своей столицей. Западные союзники и Западная Германия отвергли идею Советского Союза о нейтральном воссоединении в 1952 году, в результате чего два правительства Германии продолжали существовать бок о бок. Большая часть границы между двумя Германиямиа позже граница в Берлине была физически укреплена и жестко контролировалась Восточной Германией в 1952 и 1961 годах соответственно. Флаги двух немецких стран изначально были одинаковыми , но в 1959 году Восточная Германия сменила свой флаг . [22] Правительство Западной Германии первоначально не признавало ни новую и де-факто немецко-польскую границу , ни Восточную Германию, но позже в конечном итоге признало границу в 1972 году (с Варшавским договором 1970 года [23] [24] [25] ) и Восточная Германия в 1973 году (с Основным договором 1972 года [26] ) при применении общей политики по примирению с коммунистическими странами Востока . Правительство Восточной Германии также поощряло статус двух государств после того, как первоначально отрицало существование западногерманского государства под влиянием советской политики « мирного сосуществования ». Взаимное признание двух Германий проложило путь к широкому признанию обеих стран на международном уровне. [c] Две Германии присоединились к Организации Объединенных Наций в качестве двух отдельных стран-членов в 1973 году, а Восточная Германия отказалась от своей цели воссоединения со своими соотечественниками на Западе в результате внесения поправки в конституцию в следующем году .

Михаил Горбачев руководил страной в качестве Генерального секретаря Коммунистической партии Советского Союза с 1985 года, поскольку Советский Союз переживал период экономической и политической стагнации и, соответственно, уменьшилось вмешательство в политику Восточного блока . В 1987 году президент США Рональд Рейган произнес знаменитую речь у Бранденбургских ворот , призвав генерального секретаря СССР Михаила Горбачева « снести эту стену », которая препятствует свободе передвижения в Берлине. Стена была символом политического и экономического разделения между Востоком и Западом, разделения, которое Черчилль называл « железным занавесом ». Горбачев объявил в 1988 году, что Советский Союз откажется от доктрины Брежнева и позволит восточноевропейским странам свободно определять свои внутренние дела. [27] В начале 1989 года, в эпоху новой советской политики гласности (открытости) и перестройки (экономической реструктуризации), получившей дальнейшее развитие от Горбачева, движение «Солидарность» закрепилось в Польше. Вдохновленная другими образами смелого неповиновения , в том году по Восточному блоку прокатилась волна революций . В мае 1989 года Венгрия сняла пограничный забор. Однако демонтаж старых венгерских пограничных объектов не привел к открытию границ, и прежний строгий контроль не был отменен, а изоляция « железным занавесом» все еще сохранялась на всем ее протяжении. Открытие пограничных ворот между Австрией и Венгрией на Панъевропейском пикнике 19 августа 1989 года положило начало мирной цепной реакции, в конце которой ГДР больше не существовало, а Восточный блок распался. [3] [2] Обширная реклама запланированного пикника была сделана плакатами и листовками среди отдыхающих ГДР в Венгрии. Австрийское отделение Панъевропейского союза , которое тогда возглавлял Карл фон Габсбург , распространило тысячи брошюр с приглашением на пикник недалеко от границы в Шопроне. Это был самый крупный побег из Восточной Германии со времен строительства Берлинской стены в 1961 году. После пикника, который был основан на идее отца Карла Отто фон Габсбурга проверить реакцию СССР и Михаила Горбачева.После открытия границы десятки тысяч восточных немцев, информированных СМИ, отправились в Венгрию. [28] Реакция СМИ на Эриха Хонеккера в «Daily Mirror» от 19 августа 1989 года показала общественности на Востоке и Западе, что коммунистические правители Восточной Европы потеряли власть в своей собственной сфере власти, и что они уже не были организаторами происходящего: «Габсбурги распространяли далеко в Польшу листовки , на которых восточногерманские отдыхающие приглашались на пикник. Когда они приезжали на пикник, им дарили подарки, еду и немецкие марки, а затем их уговорили приехать на Запад». В частности, у Габсбургов и венгерского государственного министра Имре Пожгая рассматривался вопрос , даст ли Москва советским войскам , дислоцированным в Венгрии, команду на интервенцию. [29] Но с массовым исходом на Панъевропейском пикнике, последующее нерешительное поведение Социалистической единой партии Восточной Германии и невмешательство Советского Союза прорвало дамбы. Таким образом, скобка Восточного блока была сломана. [30]

Десятки тысяч восточных немцев, проинформированных СМИ, теперь направились в Венгрию, которая больше не была готова держать свои границы полностью закрытыми или заставлять свои пограничные войска применять силу оружия. К концу сентября 1989 года более 30 000 граждан Восточной Германии бежали на Запад, прежде чем ГДР запретила въезд в Венгрию, в результате чего Чехословакия осталась единственным соседним государством, куда восточные немцы могли бежать. [31] [32]

Даже тогда многие люди в Германии и за ее пределами все еще верили, что настоящего воссоединения двух стран никогда не произойдет в обозримом будущем. [33] Поворотный момент в Германии, названный Die Wende , был отмечен « Мирной революцией », приведшей к падению Берлинской стены в ночь на 9 ноября 1989 года, когда Восточная и Западная Германия впоследствии вступили в переговоры о ликвидации разделения. это было навязано немцам более четырех десятилетий назад.

28 ноября 1989 года, через две недели после падения Берлинской стены, канцлер Западной Германии Гельмут Коль объявил о программе из 10 пунктов, призывающей две Германии расширить сотрудничество с целью возможного воссоединения. [34]

Первоначально никакого графика не было предложено. Однако в начале 1990 года события быстро достигли апогея. Сначала, в марте, Партия демократического социализма — бывшая Социалистическая единая партия Германии — потерпела серьёзное поражение на первых свободных выборах в Восточной Германии . Большая коалиция была сформирована под руководством Лотара де Мезьера , лидера восточногерманского крыла Христианско -демократического союза Коля , на платформе скорейшего воссоединения. Во-вторых, экономика и инфраструктура Восточной Германии подверглись быстрому и почти полному краху. Хотя Восточная Германия долгое время считалась страной с самой сильной экономикой в советском блоке, устранение коммунистической гегемонии выявило ветхие основы этой системы. Восточногерманская марка в течение некоторого времени до событий 1989–1990 годов была почти бесполезна за пределами Восточной Германии, а коллапс восточногерманской экономики еще больше усугубил проблему.

Сразу же начались дискуссии об экстренном слиянии немецких экономик. 18 мая 1990 года два немецких государства подписали договор о валютном, экономическом и социальном союзе. Этот договор называется Vertrag über die Schaffung einer Währungs-, Wirtschafts- und Sozialunion zwischen der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland («Договор об установлении валютного, экономического и социального союза между Германской Демократической Республикой и Федеративной Республикой Германия»); [35] он вступил в силу 1 июля 1990 года, когда западногерманская немецкая марка заменила восточногерманскую марку в качестве официальной валюты Восточной Германии. Немецкая марка имела очень высокую репутацию среди восточных немцев и считалась стабильной. [36] В то время как ГДР передала суверенитет своей финансовой политики Западной Германии, Запад начал предоставлять субсидии для бюджета ГДР и системы социального обеспечения . [37] В то же время в ГДР вступили в силу многие западногерманские законы. Это создало подходящую основу для политического союза , уменьшив огромный разрыв между двумя существующими политическими, социальными и экономическими системами. [37]

Народная камера , парламент Восточной Германии, приняла резолюцию 23 августа 1990 года, провозглашающую присоединение ( Beitritt ) Германской Демократической Республики к Федеративной Республике Германия и расширение сферы применения Основного закона Федеративной Республики на территории Восточной Германии , как это разрешено статьей 23 Основного закона Западной Германии, вступившей в силу 3 октября 1990 года . Поля президенту Западногерманского Бундестага Рите Зюссмут письмом от 25 августа 1990 года. [40] Таким образом, формально процедура воссоединения посредством присоединения Восточной Германии к Западной Германии и Восточной Германии Принятие Германией Основного закона, уже действующего в Западной Германии, было инициировано как одностороннее суверенное решение Восточной Германии, как это допускалось положениями статьи 23 Основного закона Западной Германии в том виде, в каком он тогда существовал.

После принятия этой резолюции о присоединении был заключен «Договор о воссоединении Германии», [41] [42] [43], широко известный на немецком языке как « Einigungsvertrag » (Договор об объединении) или « Wiedervereinigungsvertrag » (Договор о воссоединении). между двумя немецкими государствами со 2 июля 1990 года, был подписан представителями двух правительств 31 августа 1990 года. Этот договор, официально озаглавленный Vertrag zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik über die Herstellung der Einheit Deutschlands (Договор между Федеративной Республикой Германия Германии и Германской Демократической Республики об установлении немецкого единства), был одобрен подавляющим большинством голосов в законодательных палатах обеих стран 20 сентября 1990 года (442–47 в Бундестаге Западной Германии и 299–80 в Народной палате Восточной Германии). . [44] Договор был принят Бундесратом Западной Германии на следующий день, 21 сентября 1990 г. Поправки к Основному закону Федеративной Республики, которые были предусмотрены Договором об объединении или необходимы для его реализации, были приняты Федеральным законом от 23 сентября 1990 г. что привело к включению Договора в законодательство Федеративной Республики Германия. Указанный Федеральный статут, содержащий полный текст Договора и Протоколов к нему в качестве приложения, был опубликован в Bundesgesetzblatt ( официальном журнале для публикации законов Федеративной Республики) 28 сентября 1990 года . В Демократической Республике Конституционный закон ( Verfassungsgesetz ), вводящий в действие Договор, был также опубликован 28 сентября 1990 года. [40] С принятием Договора как части своей Конституции Восточная Германия законодательно закрепила отмену своего права как отдельного государства.

В соответствии со статьей 45 Договора [46] он вступил в силу в соответствии с международным правом 29 сентября 1990 г. после обмена уведомлениями о выполнении соответствующих внутренних конституционных требований для принятия договора как в Восточной Германии, так и в Западной Германии. . Благодаря этому последнему шагу, а также в соответствии со статьей 1 Договора и в соответствии с Декларацией о присоединении Восточной Германии, представленной Федеративной Республике, Германия была официально воссоединена в 00:00 по центральноевропейскому летнему времени 3 октября 1990 года. Восточная Германия присоединилась к Федеративной Республике. как пять земель (государств) Бранденбург , Мекленбург-Передняя Померания , Саксония , Саксония-Анхальт и Тюрингия . Эти штаты были пятью первоначальными штатами Восточной Германии, но были упразднены в 1952 году в пользу централизованной системы. В рамках договора от 18 мая пять восточногерманских государств были воссозданы 23 августа. Восточный Берлин , столица Восточной Германии, воссоединился с Западным Берлином , де-факто частью Западной Германии, чтобы сформировать город Берлин , который присоединился к Федеративной Республике в качестве третьего города-государства наряду с Бременом и Гамбургом . Формально Берлин все еще находился под оккупацией союзников (которая была прекращена только позже в результате положений Договора « два плюс четыре» ), но административное слияние города и включение в расширенную Федеративную республику в качестве его столицы вступило в силу 3 октября 1990 года. , получили зеленый свет [ необходимы разъяснения ] четырьмя союзниками и были официально одобрены на заключительном заседании Контрольного совета союзников 2 октября 1990 года. На эмоциональной церемонии, ровно в полночь 3 октября 1990 года, черно -красный -золотой флаг Западной Германии — ныне флаг воссоединенной Германии — был поднят над Бранденбургскими воротами , отмечая момент воссоединения Германии.

Выбранный процесс был одним из двух вариантов, изложенных в конституции Западной Германии ( Grundgesetz или Основной закон) 1949 года для облегчения возможного воссоединения. В Основном законе говорилось, что он предназначен только для временного использования до тех пор, пока немецким народом в целом не будет принята постоянная конституция. В соответствии со статьей 23 (существовавшей тогда) этого документа, любые новые потенциальные земли могли присоединиться к Основному закону простым большинством голосов. Первые 11 государств, присоединившихся в 1949 году, составили Тризону. Западный Берлин был предложен в качестве 12-го штата, но это было юридически запрещено из-за возражений союзников, поскольку Берлин в целом юридически был четырехсторонней оккупированной территорией. Несмотря на это, политическая принадлежность Западного Берлина была к Западной Германии, и во многих областях он функционировал де-факто так, как если бы он был составной частью Западной Германии. 1 января 1957 года, перед воссоединением, территория Саара , протектората Франции (1947–1956), объединилась с Западной Германией (и, таким образом, воссоединилась с Германией) как 11-е государство Федеративной Республики; это называлось «Маленькое воссоединение», хотя сам протекторат Саар был лишь одной из спорных территорий , поскольку против его существования выступал Советский Союз.

Другой вариант был изложен в статье 146, которая предусматривала механизм постоянной конституции объединенной Германии. Этот путь повлек бы за собой формальный союз между двумя немецкими государствами, которым затем пришлось бы, среди прочего, создать новую конституцию для вновь созданной страны. Однако к весне 1990 года стало очевидно, что разработка новой конституции потребует длительных переговоров, которые откроют множество проблем в Западной Германии. Даже без этого к началу 1990 года Восточная Германия находилась в состоянии экономического и политического коллапса. Напротив, воссоединение согласно статье 23 может быть осуществлено всего за шесть месяцев. В конечном итоге, когда был подписан договор о валютном, экономическом и социальном союзе, было решено использовать более быстрый процесс, описанный в статье 23. В результате этого процесса Восточная Германия проголосовала за самороспуск и присоединение к Западной Германии, а также к территории, в которой Действующий Основной закон был просто расширен и включил в себя его составные части. [47] Таким образом, хотя юридически Восточная Германия в целом присоединилась к Федеративной Республике, составные части Восточной Германии вошли в Федеративную Республику в качестве пяти новых земель, которые провели свои первые выборы 14 октября 1990 года.

Тем не менее, хотя декларация Народной палаты о присоединении к Федеративной Республике инициировала процесс воссоединения, сам акт воссоединения (с его многочисленными конкретными положениями, условиями и оговорками, некоторые из которых требовали внесения поправок в сам Основной закон) был осуществлен конституционным путем. последующим Договором об объединении от 31 августа 1990 г.; то есть посредством обязательного соглашения между бывшей ГДР и Федеративной Республикой, которая теперь признает друг друга как отдельные суверенные государства в международном праве . [48] Затем этот договор был проголосован за вступление в силу как Народной палатой , так и Бундестагом конституционно необходимым большинством в две трети голосов, что привело, с одной стороны, к прекращению существования ГДР, а с другой - к согласованным поправкам к Основному закону. Федеративной Республики. Таким образом, хотя ГДР и заявила о своем присоединении к Федеративной Республике в соответствии со статьей 23 Основного закона, это означало принятие ею не Основного закона в его нынешнем виде, а скорее Основного закона с поправками, впоследствии измененными в соответствии с Договором об объединении. .

Юридически воссоединение не привело к созданию третьего государства из двух. Скорее, Западная Германия фактически поглотила Восточную Германию. Соответственно, в День объединения, 3 октября 1990 года, Германская Демократическая Республика прекратила свое существование, и пять новых федеративных земель на ее бывшей территории присоединились к Федеративной Республике Германия. Восточный и Западный Берлин были воссоединены как третий полноценный федеративный город-государство расширенной Федеративной Республики. Воссоединенный город стал столицей расширенной Федеративной Республики. В соответствии с этой моделью Федеративная Республика Германия, теперь расширенная за счет пяти земель бывшей ГДР и воссоединенного Берлина, продолжала существовать под той же правосубъектностью, которая была основана в мае 1949 года.

Хотя Основной закон был изменен, а не заменен конституцией как таковой, он по-прежнему разрешает принятие официальной конституции немецким народом в какой-то момент в будущем.

В контексте городского планирования , помимо множества новых возможностей и символизма воссоединения двух бывших независимых государств, воссоединение Берлина создало множество проблем. Город претерпел масштабную реконструкцию , затронувшую политическую, экономическую и культурную среду как Восточного, так и Западного Берлина. Однако «шрам», оставленный Стеной , проходящий прямо через самое сердце города, [49] имел последствия для городской среды, которые еще предстоит решить при планировании.

Объединение Берлина создало юридические, политические и технические проблемы для городской среды. Политическое разделение и физическое разделение города на протяжении более 30 лет привело к тому, что Восток и Запад разработали свои собственные городские формы, причем многие из этих различий все еще заметны по сей день. [50] Поскольку городское планирование в Германии является обязанностью городского правительства, [51] интеграция Восточного и Западного Берлина была частично осложнена тем фактом, что существующие рамки планирования устарели после падения Стены. [52] До воссоединения города План землепользования 1988 года и Генеральный план развития 1980 года определяли критерии пространственного планирования для Западного и Восточного Берлина соответственно. [52] В 1994 году они были заменены новым единым Планом землепользования. [52] Новая политика, получившая название «Критическая реконструкция», была направлена на возрождение довоенной эстетики Берлина; [53] он был дополнен документом стратегического планирования центра Берлина, озаглавленным «Рамки внутреннего городского планирования». [53]

После распада ГДР 3 октября 1990 года все проекты планирования при социалистическом тоталитарном режиме были заброшены. [54] Пустыни, открытые территории и пустые поля в Восточном Берлине подлежали перепланировке, в дополнение к площадям, ранее занимаемым Стеной и связанной с ней буферной зоной . [51] Многие из этих объектов были расположены в центральных стратегических местах воссоединенного города. [52]

_Luftballons_vom_Freundeskreis_Hannover_für_Angela_Merkel_und_Joachim_Gauck,,_(01).jpg/440px-2014-10-03_Tag_der_Deutschen_Einheit,_(108)_Luftballons_vom_Freundeskreis_Hannover_für_Angela_Merkel_und_Joachim_Gauck,,_(01).jpg)

В ознаменование дня официального объединения бывшей Восточной и Западной Германии в 1990 году 3 октября с тех пор стало официальным национальным праздником Германии — Днем немецкого единства ( Tag der deutschen Einheit ). Он заменил предыдущий национальный праздник, проводившийся в Западной Германии 17 июня в память о восточногерманском восстании 1953 года, и национальный праздник 7 октября в ГДР, посвященный основанию восточногерманского государства . [37] Альтернативной датой воссоединения мог бы стать день падения Берлинской стены, 9 ноября (1989 г.), что совпало с годовщиной провозглашения Германской республики в 1918 г. и разгрома первого гитлеровского переворота в Германии. 1923. Однако 9 ноября было также годовщиной первых крупномасштабных нацистских погромов против евреев в 1938 году ( Хрустальная ночь ), поэтому этот день считался неподходящим для национального праздника. [55] [56]

На протяжении всей холодной войны и до 1990 года воссоединение не представлялось вероятным, а существование двух немецких стран обычно рассматривалось как установленный, неизменный факт. [57] Гельмут Коль кратко затронул этот вопрос во время федеральных выборов в Западной Германии в 1983 году , заявив, что, несмотря на его веру в национальное единство Германии, это не будет означать «возврат к национальному государству прежних времен». В 1980-х годах оппозиция единой немецкой стране и поддержка длительного мирного сосуществования между двумя немецкими странами были очень распространены среди левых партий Западной Германии, особенно СДПГ и зеленых . Раздел Германии считался необходимым для поддержания мира в Европе, а появление еще одного немецкого государства также считалось возможной угрозой для западногерманской демократии. Немецкий публицист Петер Бендер писал в 1981 году: «Учитывая роль, которую Германия сыграла в истоках обеих мировых войн, Европа не может, а немцы не должны желать нового немецкого рейха, суверенного национального государства. Такова логика истории. что, как заметил Бисмарк , более точно, чем контрольная палата прусского правительства». [57] Мнения о воссоединении были не только очень партийными, но и поляризованными по многим социальным разногласиям: немцы в возрасте 35 лет и моложе были против объединения, тогда как респонденты старшего возраста были более благосклонны; Аналогично, немцы с низкими доходами были склонны выступать против воссоединения, тогда как более богатые респонденты, скорее всего, поддержали его. [58] В конечном итоге опрос, проведенный в июле 1990 года, показал, что основным мотивом воссоединения была экономическая озабоченность, а не национализм. [58] [59]

Опросы общественного мнения, проведенные в конце 1980-х годов, показали, что молодые восточные немцы и западные немцы считали друг друга иностранцами и не считали себя единой нацией. [57] Генрих Август Винклер отмечает, что «оценка соответствующих данных в Немецком архиве в 1989 году показала, что ГДР воспринималась значительной частью молодого поколения как чужая нация с другим социальным строем, которая больше не была частью Германии». [57] Винклер утверждает, что воссоединение было не продуктом общественного мнения, а скорее «кризисным управлением на самом высоком уровне». [57] Поддержка объединенной Германии упала, как только осенью 1989 года перспектива этого стала осязаемой реальностью. [58] Опрос, проведенный в декабре 1989 года журналом Der Spiegel , показал сильную поддержку сохранения Восточной Германии как отдельного государства. [60] Однако члены СЕПГ были перепредставлены среди респондентов, составляя 13% населения, но 23% опрошенных. Сообщая о студенческом протесте в Восточном Берлине 4 ноября 1989 года, Элизабет Понд отметила, что «практически никто из демонстрантов, опрошенных западными репортерами, не говорил, что хочет объединения с Федеративной Республикой». [60] В Западной Германии, когда стало ясно, что ведутся переговоры о курсе быстрого объединения, общественность отреагировала с беспокойством. [58] В феврале 1990 года две трети западных немцев считали темп объединения «слишком быстрым». Западные немцы также враждебно относились к пришельцам с Востока - согласно опросу, проведенному в апреле 1990 года, только 11% западных немцев приветствовали беженцев из Восточной Германии. [61]

После объединения национальный раскол сохранялся: исследование, проведенное Институтом Алленсбаха в апреле 1993 года, показало, что только 22% западных немцев и 11% восточных немцев считают себя одной нацией. [57] Долорес Л. Августин заметила, что «чувство единства, которое испытывали восточные немцы и западные немцы в период эйфории после падения стены, оказалось слишком преходящим», поскольку старые разделения сохранялись, и немцы не только до сих пор считали себя двумя отдельными людьми, но действовали также в соответствии со своими отдельными, региональными интересами. [62] Это состояние ума стало известно как Mauer im Kopf («стена в голове»), что позволяет предположить, что, несмотря на падение Берлинской стены , «психологическая стена» все еще существовала между восточными и западными немцами. Августин утверждает, что, несмотря на сопротивление политическому режиму Восточной Германии, он по-прежнему представляет историю и идентичность восточных немцев. Объединение вызвало негативную реакцию, а Treuhandanstalt , агентство, созданное для проведения приватизации, было обвинено в создании массовой безработицы и бедности на Востоке. [62]

Влиятельной частью противников воссоединения были так называемые антигерманцы . [63] Выйдя из студенческих левых, антинемцы поддерживали Израиль и решительно выступали против немецкого национализма , утверждая, что появление единого немецкого государства также приведет к возвращению фашизма ( нацизма ). Они считали социальную и политическую динамику Германии 1980-х и 1990-х годов сопоставимой с динамикой 1930-х годов, осуждая зарождающийся антисионизм , объединительные настроения и возрождение пангерманизма . Герман Л. Гремлица , покинувший СДПГ в 1989 году из-за ее поддержки объединения Германии, был оттолкнут всеобщей поддержкой объединения среди большинства основных партий, заявив, что это напомнило ему « социал-демократов , присоединившихся к национал-социалистам (нацистам) в пении национальный гимн Германии в 1933 году, после провозглашения Гитлером своей внешней политики». Несколько тысяч человек присоединились к антинемецким протестам 1990 года против воссоединения Германии. [63]

По словам Стивена Брокманна, этнические меньшинства, особенно в Восточной Германии, опасались воссоединения Германии и выступали против него. [59] Он отмечает, что «на протяжении 1990 года в ГДР наблюдался рост насилия со стороны правых, с частыми случаями избиений, изнасилований и драк, связанных с ксенофобией», что привело к блокировке полиции в Лейпциге в ночь воссоединения. [59] Напряженность в отношениях с Польшей была высокой, и многие внутренние этнические меньшинства, такие как сербы, опасались дальнейшего перемещения или политики ассимиляции; сорбы получили правовую защиту в ГДР и опасались, что права, предоставленные им в Восточной Германии, не будут включены в закон будущей объединенной Германии. В конечном итоге, никакое положение о защите этнических меньшинств не было включено в реформу Основного закона после объединения в 1994 году. [64] Хотя политики призывали к принятию нового многоэтнического общества, многие не желали «отказываться от его традиционного расового определения». немецкой национальности». Феминистские группы также выступали против объединения, поскольку законы об абортах в Восточной Германии были менее строгими, чем в Западной Германии, а прогресс, достигнутый ГДР в отношении благосостояния женщин , такого как юридическое равенство , уход за детьми и финансовая поддержка, был «все менее впечатляющим или не существует на Западе». [59] Оппозиция была также распространена среди еврейских кругов, которые имели особый статус и права в Восточной Германии. Некоторые еврейские интеллектуалы, такие как Гюнтер Кунерт, выразили обеспокоенность по поводу того, что евреев изображают как часть социалистической элиты Восточной Германии, учитывая, что евреи обладают уникальными правами, такими как право путешествовать на запад. [65]

В интеллектуальных кругах также существовало значительное сопротивление объединению. Криста Вольф и Манфред Столпе подчеркнули необходимость формирования восточногерманской идентичности, в то время как «гражданские инициативы, церковные группы и интеллектуалы с первого часа начали выдавать мрачные предупреждения о возможном аншлюсе ГДР со стороны Федеративной Республики». [59] [62] Многие восточногерманские оппозиционеры и реформаторы выступали за «третий путь» независимой, демократической социалистической Восточной Германии. [59] Штефан Хейм утверждал, что сохранение ГДР было необходимо для достижения идеала демократического социализма , призывая восточных немцев выступить против «капиталистической аннексии» в пользу демократического социалистического общества. [59] Писатели как на Востоке, так и на Западе были обеспокоены разрушением восточногерманской или западногерманской культурной идентичности соответственно; в «Прощай с литературой Федеративной Республики» Фрэнк Ширмахер заявляет, что литература обоих государств занимала центральное место в сознании и уникальной идентичности обеих наций, и эта недавно развитая культура теперь находится под угрозой из-за надвигающегося воссоединения. [59] Дэвид Гресс заметил, что существует «влиятельная точка зрения, встречающаяся в значительной степени, но ни в коем случае не только среди немецких и международных левых сил», которая рассматривает «стремление к объединению либо как зловещее, маскирующее возрождение агрессивных националистических устремлений, либо как материалистическое стремление к объединению». ". [66]

Günter Grass, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1999, also expressed his vehement opposition to the unification of Germany, citing his tragic memories of World War II as the reason.[59] According to Grass, the emergence of National Socialism and the Holocaust had deprived Germany of its right to exist as a unified nation state: he wrote: "Historical responsibility dictates opposition to reunification, no matter how inevitable it may seem."[59] He also claimed that "national victory threatens a cultural defeat", as "blooming of German culture and philosophy is possible only at times of fruitful national disunity", and also cited Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's opposition to the first unification of Germany in 1871:[59] Goethe wrote: "Frankfurt, Bremen, Hamburg, Lübeck are large and brilliant, and their impact on the prosperity of Germany is incalculable. Yet, would they remain what they are if they were to lose their independence and be incorporated as provincial cities into one great German Empire? I have reason to doubt this."[67] Grass also condemned the unification as philistinist and purely materialist, calling it "the monetary fetish, by now devoid of all joy." Heiner Müller supported Grass' criticism of the unification process, warning East Germans: "We will be a nation without dreams, we will lose our memories, our past, and therefore also our ability to hope."[59] British historian Richard J. Evans made a similar argument, criticizing the unification as driven solely by "consumerist appetites whetted by years of watching West German television advertisements".[66]

For decades, West Germany's allies stated their support for reunification. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who speculated that a country that "decided to kill millions of Jewish people" in the Holocaust "will try to do it again", was one of the few world leaders to publicly oppose it. As reunification became a realistic possibility, however, significant NATO and European opposition emerged in private.[68]

.jpg/440px-RIAN_archive_850809_General_Secretary_of_the_CPSU_CC_M._Gorbachev_(crop).jpg)

A poll of four countries in January 1990 found that a majority of surveyed Americans and French supported reunification, while British and Poles were more divided: 69 percent of Poles and 50 percent of French and British stated that they worried about a reunified Germany becoming "the dominant power in Europe". Those surveyed stated several concerns, including Germany again attempting to expand its territory, a revival of Nazism, and the German economy becoming too powerful. While British, French, and Americans favored Germany remaining a member of NATO, a majority of Poles supported neutrality for the reunified state.[70]

The key ally was the United States. Although some top American officials opposed quick unification, Secretary of State James A. Baker and President George H. W. Bush provided strong and decisive support to Kohl's proposals.[71][72][d]

We defeated the Germans twice! And now they're back!

— Margaret Thatcher, December 1989[74]

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was one of the most vehement opponents of German reunification. Before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Thatcher told Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev that neither the United Kingdom nor, according to her, Western Europe, wanted the reunification of Germany. Thatcher also clarified that she wanted the Soviet leader to do what he could to stop it, telling Gorbachev, "We do not want a united Germany".[75] Although she welcomed East German democracy, Thatcher worried that a rapid reunification might weaken Gorbachev, and she favored Soviet troops staying in East Germany as long as possible to act as a counterweight to a united Germany.[68][76]

Thatcher, who carried in her handbag a map of Germany's 1937 borders to show others the "German problem", feared that Germany's "national character", size, and central location in Europe would cause it to be a "destabilizing rather than a stabilizing force in Europe".[76] In December 1989, she warned fellow European Community leaders at a Council summit in Strasbourg which Kohl attended, "We defeated the Germans twice! And now they're back!".[68][74] Although Thatcher had stated her support for German self-determination in 1985,[76] she now argued that Germany's allies only supported reunification because they did not believe it would ever happen.[68] Thatcher favored a transition period of five years for reunification, during which the two Germanies would remain separate states. Although she gradually softened her opposition, as late as March 1990, Thatcher summoned historians and diplomats to a seminar at Chequers to ask "How dangerous are the Germans?",[76][74] and the French ambassador in London reported that Thatcher told him, "France and Great Britain should pull together today in the face of the German threat."[77][78]

The pace of events surprised the French, whose Foreign Ministry had concluded in October 1989 that reunification "does not appear realistic at this moment".[79] A representative of French President François Mitterrand reportedly told an aide to Gorbachev, "France by no means wants German reunification, although it realises that in the end, it is inevitable."[75] At the Strasbourg summit, Mitterrand and Thatcher discussed the fluidity of Germany's historical borders.[68] On 20 January 1990, Mitterrand told Thatcher that a unified Germany could "make more ground than even Adolf had".[77] He predicted that "bad" Germans would reemerge,[74] who might seek to regain former German territory lost after World War II and would likely dominate Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia,[76] leaving "only Romania and Bulgaria for the rest of us". The two leaders saw no way to prevent reunification, however, as "None of us was going to declare war on Germany".[68] Mitterrand recognized before Thatcher that reunification was inevitable and adjusted his views accordingly; unlike her, he was hopeful that participation in a single currency and other European institutions could control a united Germany.[76] Mitterrand still wanted Thatcher to publicly oppose unification, however, to obtain more concessions from Germany.[74]

I love Germany so much that I prefer to see two of them.

— Giulio Andreotti, Prime Minister of Italy, quoting François Mauriac[80]

Ireland's Taoiseach, Charles Haughey, supported German reunification and he took advantage of Ireland's presidency of the European Economic Community to call for an extraordinary European summit in Dublin in April 1990 to calm the fears held of fellow members of the EEC.[81][82][83] Haughey saw similarities between Ireland and Germany, and said "I have expressed a personal view that coming as we do from a country which is also divided many of us would have sympathy with any wish of the people of the two German States for unification".[84] Der Spiegel later described other European leaders' opinion of reunification at the time as "icy". Italy's Giulio Andreotti warned against a revival of "pan-Germanism" and the Netherlands's Ruud Lubbers questioned the German right to self-determination. They shared Britain's and France's concerns over a return to German militarism and the economic power of a reunified country. The consensus opinion was that reunification, if it must occur, should not occur until at least 1995 and preferably much later.[68] Andreotti, quoting François Mauriac, joked "I love Germany so much that I prefer to see two of them".[80]

The victors of World War II—France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States, comprising the Four-Power Authorities—retained authority over Berlin, such as control over air travel and its political status. From the onset, the Soviet Union sought to use reunification as a way to push Germany out of NATO into neutrality, removing nuclear weapons from its territory. However, West Germany misinterpreted a 21 November 1989 diplomatic message on the topic to mean that the Soviet leadership already anticipated reunification only two weeks after the Wall's collapse. This belief, and the worry that his rival Genscher might act first, encouraged Kohl on 28 November to announce a detailed "Ten Point Program for Overcoming the Division of Germany and Europe". While his speech was very popular within West Germany, it caused concern among other European governments, with whom he had not discussed the plan.[68][85]

The Americans did not share the Europeans' and Soviets' historical fears over German expansionism; Condoleezza Rice later recalled,[86]

The United States—and President George H. W. Bush—recognized that Germany went through a long democratic transition. It was a good friend, it was a member of NATO. Any issues that existed in 1945, it seemed perfectly reasonable to lay them to rest. For us, the question wasn't should Germany unify? It was how and under what circumstances? We had no concern about a resurgent Germany...

The United States wished to ensure, however, that Germany would stay within NATO. In December 1989, the administration of President George H. W. Bush made a united Germany's continued NATO membership a requirement for supporting reunification. Kohl agreed, although less than 20 percent of West Germans supported remaining within NATO. Kohl also wished to avoid a neutral Germany, as he believed that would destroy NATO, cause the United States and Canada to leave Europe, and cause Britain and France to form an anti-German alliance. The United States increased its support of Kohl's policies, as it feared that otherwise Oskar Lafontaine, a critic of NATO, might become Chancellor.[68]Horst Teltschik, Kohl's foreign policy advisor, later recalled that Germany would have paid "100 billion deutschmarks" if the Soviets demanded it. The USSR did not make such great demands, however, with Gorbachev stating in February 1990 that "[t]he Germans must decide for themselves what path they choose to follow". In May 1990, he repeated his remark in the context of NATO membership while meeting Bush, amazing both the Americans and Germans.[68] This removed the last significant roadblock to Germany being free to choose its international alignments, though Kohl made no secret that he intended for the reunified Germany to inherit West Germany's seats in NATO and the EC.

During a NATO–Warsaw Pact conference in Ottawa, Canada; Genscher persuaded the four powers to treat the two Germanies as equals instead of defeated junior partners and for the six nations to negotiate alone. Although the Dutch, Italians, Spanish, and other NATO powers opposed such a structure, which meant that the alliance's boundaries would change without their participation, the six nations began negotiations in March 1990. After Gorbachev's May agreement on German NATO membership, the Soviets further agreed that Germany would be treated as an ordinary NATO country, with the exception that former East German territory would not have foreign NATO troops or nuclear weapons. In exchange, Kohl agreed to reduce the sizes of the militaries of both West and East Germany, renounce weapons of mass destruction, and accept the postwar Oder–Neisse line as Germany's eastern border. In addition, Germany agreed to pay about 55 billion deutschmarks to the Soviet Union in gifts and loans, the equivalent of eight days of the West German GDP.[68] To oppose German reunification, the British insisted to the end, against Soviet opposition, that NATO be allowed to hold maneuvers in the former East Germany. Thatcher later wrote that her opposition to reunification had been an "unambiguous failure".[76]

.jpg/440px-Bundesarchiv_B_145_Bild-F086568-0046,_Leipzig,_ausgeschlachteter_PKW_Trabant_(Trabbi).jpg)

On 15 March 1991, the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany—that had been signed in Moscow back on 12 September 1990 by the two German states that then existed (East and West Germany) on one side and by the four principal Allied powers (the United Kingdom, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States) on the other—entered into force, having been ratified by the Federal Republic of Germany (after the unification, as the united Germany) and by the four Allied states. The entry into force of that treaty (also known as the "Two Plus Four Treaty", in reference to the two German states and four Allied governments that signed it) put an end to the then-remaining limitations on German sovereignty and the ACC that resulted from the post-World War II arrangements. After the Americans intervened,[68] both the United Kingdom and France ratified the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany in September 1990. The Treaty entered into force on 15 March 1991, in accordance with Article 9 of the Two Plus Four Treaty, it entered into force as soon as all ratifications were deposited with the Government of Germany, thus finalizing the reunification for purposes of international law. The last party to ratify the treaty was the Soviet Union, that deposited its instrument of ratification on 15 March 1991. The Supreme Soviet of the USSR only gave its approval to the ratification of the treaty on 4 March 1991, after a hefty debate. Even prior to the ratification of the Treaty, the operation of all quadripartite Allied institutions in Germany was suspended, with effect from the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990 and pending the final ratification of the Two Plus Four Treaty, pursuant to a declaration signed in New York on 1 October 1990 by the foreign ministers of the four Allied Powers, that was witnessed by ministers of the two German states then in existence, and that was appended text of the Two Plus Four Treaty.[87] However, the Soviets cited their occupation rights for the last time as late as on 13 March 1991, just two days before the Treaty became effective, when the Honeckers were enabled by Soviet hardliners to flee Germany on a military jet to Moscow from the Soviet-controlled Sperenberg Airfield, with the German Federal Government being notified of this in advance of just one hour.[88]

Under the treaty on final settlement (which should not be confused with the Unification Treaty that was signed only between the two German states), the last Allied forces still present in Germany left in 1994, in accordance with article 4 of the treaty, that set 31 December 1994 as the deadline for the withdrawal of the remaining Allied forces. The bulk of Russian ground forces left Germany on 25 June 1994 with a military parade of the 6th Guards Motor Rifle Brigade in Berlin. This was followed by the closure of the United States Army Berlin command on 12 July 1994, an event that was marked by a casing of the colors ceremony witnessed by President Bill Clinton. The withdrawal of the last Russian troops (the Russian Army's Western Group of Forces) was completed on 31 August 1994, and the event was marked by a military ceremony in the Treptow Park in Berlin, with the presence of Russian President Yeltsin and German Chancellor Kohl.[89] Although the bulk of the British, American, and French Forces had left Germany even before the departure of the Russians, the Western Allies kept a presence in Berlin until the completion of the Russian withdrawal, and the ceremony marking the departure of the remaining Forces of the Western Allies was the last to take place: on 8 September 1994,[90] a Farewell Ceremony in the courtyard of the Charlottenburg Palace, with the presence of British Prime Minister John Major, American Secretary of State Warren Christopher, French President François Mitterrand, and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, marked the withdrawal of the British, American and French Occupation Forces from Berlin, and the termination of the Allied occupation in Germany.[89] Thus, the removal of the Allied presence took place a few months before the final deadline.

Article 5 banned the deployment of nuclear weapons in the territory previously controlled by the GDR and well as a ban on stationing non-German military personnel.[91]

On 14 November 1990, Germany and Poland signed the German–Polish Border Treaty, finalizing Germany's eastern boundary as permanent along the Oder–(Lusatian/Western) Neisse line, and thus, renouncing any claims[92] to most of Silesia, East Brandenburg, Farther Pomerania, and the southern area of the former province of East Prussia (they are called the "Recovered Territories" by Poland as they were once ruled by Piast Poland).[e] The following month, the first all-German free elections since 1932 were held, resulting in an increased majority for the coalition government of Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

As for the German–Polish Border Treaty, it was approved by the Polish Sejm on 26 November 1991 and the German Bundestag on 16 December 1991, and entered into force with the exchange of the instruments of ratification on 16 January 1992. The confirmation of the border between Germany and Poland was required of Germany by the four Allied countries in the Two Plus Four Treaty. The Treaty was later supplemented by the Treaty of Good Neighbourship between the two countries which took effect on 16 January 1992 and ensured the few remaining Germans in Poland (in Upper Silesia) were treated better by the government.

The reunification made Germany into a great power in the world again. The practical result of the chosen legal model of the unification (the incorporation of the territory of German Democratic Republic by the Federal Republic of Germany, and the continuation of the legal personality of the now enlarged Federal Republic) is that the expanded Federal Republic of Germany inherited the old West Germany's seats at the UN, NATO, the European Communities, and other international organizations. It also continued to be a party to all the treaties the old West Germany signed prior to the moment of reunification. The Basic Law and statutory laws that were in force in the Federal Republic, as amended in accordance with the Unification Treaty, continued automatically in force but now applied to the expanded territory. Also, the same President, Chancellor (Prime Minister), and Government of the Federal Republic remained in office, but their jurisdiction now included the newly acquired territory of the former East Germany.

To facilitate this process and to reassure other countries, fundamental changes were made to the German constitution. The Preamble and Article 146 were amended, and Article 23 was replaced, but the deleted former Article 23 was applied as the constitutional model to be used for the 1990 reunification. Hence, prior to the five "New Länder" of East Germany joining, the Basic Law was amended to indicate that all parts of Germany would then be unified such that Germany could now no longer consider itself constitutionally open to further extension to include the former eastern territories of Germany, that were now parts of Poland and Russia (the German territory the former USSR annexed was a part of Russia-a Soviet member state) and were settled by Poles and Russians respectively. The changes effectively formalized the Oder–Neisse line as Germany's permanent eastern border. These amendments to the Basic Law were mandated by Article I, section 4 of the Two Plus Four Treaty.[citation needed]

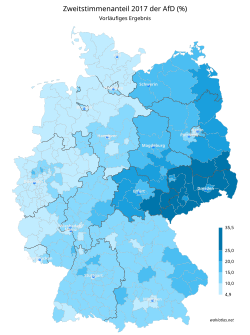

Vast differences between former East Germany and West Germany in lifestyle, wealth, political beliefs, and other matters remain, and it is therefore still common to speak of eastern and western Germany distinctly. It is often referred to as the "wall in the head" (Mauer im Kopf).[93] Ossis (Easterners) are stereotyped as racist, poor, and largely influenced by Russian culture,[94] while Wessis (Westerners) are usually considered snobbish, dishonest, wealthy, and selfish. East Germans indicate a dissatisfaction with the status quo and cultural alienation from the rest of Germany, and a sense that their cultural heritage is not acknowledged enough in the now unified Germany. The West, on the other hand, has become uninterested in what the East has to say, and this has led to more resentment toward the East, exacerbating the divide. Both the West and the East have failed to sustain an openminded dialogue, and the failure to grasp the effects of the institutional path dependency has increased the frustration each side feels.[95]

The economy of eastern Germany has struggled since unification, and large subsidies are still transferred from west to east. Economically, eastern Germany has had a sharp rise of 10 percent to West Germany's 5 percent. Western Germany also still holds 56 percent of the GDP. Part of this disparity between the East and the West lies in the Western labor unions' demand for high-wage pacts in an attempt to prevent "low-wage zones". This caused many Germans from the East to be outpriced in the market, adding to the slump in businesses in eastern Germany as well as the rising unemployment.[96] The former East German area has often been compared[by whom?] to the underdeveloped Southern Italy and the Southern United States during Reconstruction after the American Civil War. While the economy of eastern Germany has recovered recently, the differences between East and West remain present.[97][98]

Politicians and scholars have frequently called for a process of "inner reunification" of the two countries and asked whether there is "inner unification or continued separation".[99] "The process of German unity has not ended yet", proclaimed Chancellor Angela Merkel, who grew up in East Germany, in 2009.[100] Nevertheless, the question of this "inner reunification" has been widely discussed in the German public, politically, economically, culturally, and also constitutionally since 1989.

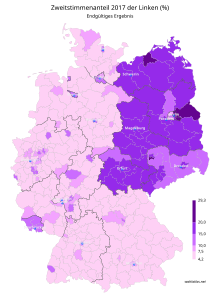

Politically, since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the successor party of the former East German socialist state party has become a major force in German politics. It was renamed PDS, and, later, merged with the Western leftist party WASG to form the Left Party (Die Linke).

Constitutionally, the Basic Law of West Germany (Grundgesetz) provided two pathways for unification. The first was the implementation of a new all-German constitution, safeguarded by a popular referendum. Actually, this was the original idea of the Grundgesetz in 1949: it was named a "basic law" instead of a "constitution" because it was considered provisional.[f] The second way was more technical: the implementation of the constitution in the East, using a paragraph originally designed for the West German states (Bundesländer) in case of internal reorganization like the merger of two states. While this latter option was chosen as the most feasible one, the first option was partly regarded as a means to foster the "inner reunification".[102][103]A public manifestation of coming to terms with the past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung) is the existence of the so-called Birthler-Behörde, the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records, which collects and maintains the files of the East German security apparatus.[104]

The economic reconstruction of former East Germany following the reunification required large amounts of public funding which turned some areas into boom regions, although overall unemployment remains higher than in the former West.[105] Unemployment was part of a process of deindustrialization starting rapidly after 1990. Causes for this process are disputed in political conflicts up to the present day. Most times bureaucracy and lack of efficiency of the East German economy are highlighted and the deindustrialization is seen as an inevitable outcome of the Wende. But many critics from East Germany point out that it was the shock-therapy style of privatization that did not leave room for East German enterprises to adapt, and that alternatives like a slow transition had been possible.[g]

Reunification did, however, lead to a large rise in the average standard of living in former East Germany, and a stagnation in the West as $2 trillion in public spending was transferred East.[108] Between 1990 and 1995, gross wages in the east rose from 35 percent to 74 percent of western levels, while pensions rose from 40 percent to 79 percent.[109] Unemployment reached double the western level as well. West German cities close to the former border of East and West Germany experienced a disproportionate loss of market access[clarification needed] relative to other West German cities which were not as greatly affected by the reunification of Germany.[110]

While the fall of the Berlin Wall had broad economic, political, and social impacts globally, it also had significant consequence for the local urban environment. In fact, the events of 9 November 1989 saw East Berlin and West Berlin, two halves of a single city that had ignored one another for the better part of 40 years, finally "in confrontation with one another".[111] There was a belief in the city that, after 40 years of division, the unified city would be well placed to become a major metropolis.[112][53]

.jpg/440px-Landmark_Traffic_(26992261693).jpg)

Another key priority was reestablishing Berlin as the seat of government of Germany, and this required buildings to serve government needs, including the "redevelopment of sites for scores of foreign embassies".[51]

With respect to redefining the city's identity, emphasis was placed on restoring Berlin's traditional landscape. "Critical Reconstruction" policies sought to disassociate the city's identity from its Nazi and socialist legacy, though some remnants were preserved, with walkways and bicycle paths established along the border strip to preserve the memory of the Wall.[51] In the center of East Berlin, much of the modernist heritage of the East German state was gradually removed.[54] Unification of Berlin saw the removal of politically motivated street names and monuments in the East in an attempt to reduce the socialist legacy from the face of East Berlin.[53]

Immediately following the fall of the Wall, Berlin experienced a boom in the construction industry.[50] Redevelopment initiatives saw Berlin turn into one of the largest construction sites in the world through the 1990s and early 2000s.[52]

The fall of the Wall also had economic consequences. Two German systems covering distinctly divergent degrees of economic opportunity suddenly came into intimate contact.[113] Despite development of sites for commercial purposes, Berlin struggled to compete in economic terms with Frankfurt which remained the financial capital of the country, as well as with other key West German centers such as Munich, Hamburg, Stuttgart and Düsseldorf.[114][115] The intensive building activity directed by planning policy resulted in the over-expansion of office space, "with a high level of vacancies in spite of the move of most administrations and government agencies from Bonn".[50][116]

Berlin was marred by disjointed economic restructuring, associated with massive deindustrialisation.[114][115] Economist Oliver Marc Hartwich asserts that, while the East undoubtedly improved economically, it was "at a much slower pace than [then Chancellor Helmut] Kohl had predicted".[117] Wealth and income inequality between former East and West Germany continued for decades after reunification. On average, adults in the former West Germany had assets worth 94,000 euros in 2014 as compared to the adults in the former communist East Germany which had just over 40,000 euros in assets.[118]The fall of the Berlin Wall and the factors described above led to mass migration from East Berlin and East Germany, producing a large labor supply shock in the West.[113] Emigration from the East, totaling 870,000 people between 1989 and 1992 alone,[119] led to worse employment outcomes for the least-educated workers, for blue-collar workers, for men, and for foreign nationals.[113]

At the close of the century, it became evident that despite significant investment and planning, Berlin was unlikely to retake "its seat between the European Global Cities of London and Paris", primarily due to the fact that Germany's financial and commercial capital is located elsewhere (Frankfurt) than the administrative one (Berlin), in resemblance of Italy (Milan vs Rome), Switzerland (Zürich vs Bern), Canada (Toronto vs Ottawa), Australia (Sydney vs Canberra), the US (New York City vs Washington, DC) or the Netherlands (Amsterdam vs The Hague), as opposed to London, Paris, Madrid, Vienna, Warsaw or Moscow which combine both roles.[53]

Yet, ultimately, the disparity between East and West portions of Berlin has led to the city achieving a new urban identity. A number of locales of East Berlin, characterized by dwellings of in-between use of abandoned space for little to no rent, have become the focal point and foundation of Berlin's burgeoning creative activities.[120] According to Berlin Mayor Klaus Wowereit, "the best that Berlin has to offer, its unique creativity. Creativity is Berlin's future."[120] Overall, the Berlin government's engagement in creativity is strongly centered on marketing and promotional initiatives instead of creative production.[121]

The subsequent economic restructuring and reconstruction of eastern Germany resulted in significant costs, especially for western Germany, which paid large sums of money in the form of the Solidaritätszuschlag (German: [zolidaʁiˈtɛːt͡st͡suːˌʃlaːk] , Solidarity Surcharge) in order to rebuild the east German infrastructure. In addition, the immensely advantageous exchange rate of 1:1 between the West German Deutschmark to the East German mark meant that East Germans could trade in their almost worthless marks for and receive wages in West German currency. This dealt a major blow to the West German budget in the coming few years.[122] The cost of German reunification for the federal government is estimated to be between 1.5 and 2 trillion euros.[123][124][125]

According to a 2019 survey conducted by Pew Research Center, 89 percent of Germans living in both the West and East believe that reunification was good for Germany, with slightly more in East than West Germany supporting it.[126] Around 83 percent of East Germans approve of and 13 percent disapprove of eastern Germany's transition to a market economy, with the rest saying they were not sure.[127] Life satisfaction in both the East and West has substantially increased since 1991, with 15 percent of East Germans placing their life satisfaction somewhere between 7 and 10 on a 0 to 10 scale in 1991, changing to 59 percent in 2019. For West Germans, this change over the same time period was from 52 to 64 percent.[128] However, the 2019 annual reunification report by the German government found that 57% East Germans felt like second-class citizens, and 38% saw the reunification as a success – this figure declined to 20% amongst people under 40.[129][130]

In 2023, a poll found that 40% of East Germans identify as East Germans rather than German which was 52%.[131][132]

Additionally, German reunification was useful in generating wealth for those Eastern household households who already had ties with the West. Those who lived in West Germany and had social ties to the East experienced a six percent average increase in their wealth in the six years following the fall of the Wall, which more than doubled that of households who did not possess the same connections.[133] Entrepreneurs who worked in areas with strong social ties to the East saw their incomes increase as well. Incomes for this group increased at an average rate of 8.8 percent over the same six-year period following reunification. Similarly, those in the East who possessed connections to the West saw their household income increase at a positive rate in each of the six years following reunification.[133] Those in their regions who lacked the same ties did not see this benefit.[133]

The fall of the Berlin Wall proved disastrous for the East German labour unions, whose bargaining power was undermined by labour reforms and companies offshoring production to low-wage East European neighbouring countries. Membership of trade unions and associations sharply declined in the mid-1990s, and collective wage and salary agreements became increasingly uncommon. As the result, average nominal compensation per employee in East Germany "fell to very low levels" after the unification. Labour reforms implemented after the unification focused on reducing costs for companies and dismantled East German wage and social security regulations in favour of incentivizing employers to create jobs. The low-wage sector in Germany expanded, and the share of employees in low-paid employment amounted to 20% of the workforce by 2009.[134]

Germany was not the only country that had been divided into two states (1949–1990) due to the Cold War. Korea (1945–present), China (1949–present), Yemen (1967–1990), and Vietnam (1954–1976) were or remain separated through the establishment of "Western-(free) Capitalist" and "Eastern-Communist" zones or former occupations.

Korea and Vietnam suffered severely from this division in the Korean War (1950–1953) and Vietnam War (1955–1975) respectively, which caused heavy economic and civilian damage.[citation needed] However, German separation did not result in another war.

Moreover, Germany is the only one of these countries that has managed to achieve a peaceful reunification without subsequent violent conflict. For instance, Vietnam achieved reunification after the war under the communist government of North Vietnam in 1976, and Yemen achieved peaceful reunification in 1990 but then suffered a civil war which delayed the reunification process. North and South Korea as well as Mainland China and Taiwan still struggle with high political tensions and huge economic and social disparities, making a possible reunification an enormous challenge.[135][136] With China, the Taiwan independence movement makes Chinese unification more difficult. East and West Germany today also still have differences in economy and social ideology, similar to North and South Vietnam, a legacy of the separation that the German government is trying to equalize.

Throughout the fall, two-thirds of all respondents welcomed the GDR refugees; in December 1989, however, barely one-quarter expressed full understanding for people still emigrating, and the support quickly dwindled to just 11 percent by April 1990.