Балтимор [a] — самый густонаселенный город в американском штате Мэриленд . С населением 585 708 человек по переписи 2020 года это 30-й по численности населения город США . [15] Балтимор был назначен независимым городом Конституцией Мэриленда [b] в 1851 году и является самым густонаселенным независимым городом в стране. По состоянию на 2020 год население столичного района Балтимора составляло 2 838 327 человек, что является 20-м по величине столичным районом в стране. [16] В совокупности объединенная статистическая область Вашингтон-Балтимор (CSA) имела население 2020 года 9 973 383 человека, что является третьим по величине в стране. [16] Хотя город не расположен в пределах или под административной юрисдикцией какого-либо округа штата, он является частью региона Центральный Мэриленд вместе с окружающим округом, который разделяет его название .[update]

Территория, на которой сейчас находится Балтимор, использовалась палеоиндейцами в качестве охотничьих угодий . В начале 1600-х годов там начали охотиться саскуэханноки . [17] Люди из провинции Мэриленд основали порт Балтимор в 1706 году для поддержки торговли табаком с Европой и основали город Балтимор в 1729 году. Во время Войны за независимость США Второй Континентальный конгресс , бежавший из Филадельфии до ее падения под натиском британских войск , перенес свои заседания в Дом Генри Файта на Уэст-Балтимор-стрит с декабря 1776 года по февраль 1777 года, что позволило Балтимору на короткое время стать столицей страны , прежде чем он вернулся в Филадельфию в марте 1777 года. Битва за Балтимор стала поворотным моментом во время войны 1812 года , завершившись неудачной британской бомбардировкой форта Мак-Генри , во время которой Фрэнсис Скотт Ки написал стихотворение, которое станет « Звездно-полосатым знаменем », назначенным национальным гимном в 1931 году. [18] Во время бунта на Пратт-стрит в 1861 году город был местом из самых ранних проявлений насилия, связанных с Гражданской войной в США .

Железная дорога Балтимор и Огайо , старейшая в стране, была построена в 1830 году и закрепила статус Балтимора как транспортного узла, предоставив производителям Среднего Запада и Аппалачей доступ к порту города . Внутренняя гавань Балтимора была вторым по величине портом въезда для иммигрантов в США и крупным производственным центром. [19] После спада в крупном производстве, тяжелой промышленности и реструктуризации железнодорожной отрасли Балтимор перешел к экономике, ориентированной на услуги . Больница и университет Джонса Хопкинса являются ведущими работодателями. [20] Балтимор является домом для Baltimore Orioles из Высшей лиги бейсбола и Baltimore Ravens из Национальной футбольной лиги .

Многие районы Балтимора имеют богатую историю. Город является домом для некоторых из самых ранних исторических районов Национального реестра в стране, включая Феллс-Пойнт , Федерал-Хилл и Маунт-Вернон . В Балтиморе больше общественных статуй и памятников на душу населения, чем в любом другом городе страны. [21] Почти треть зданий (более 65 000) обозначены как исторические в Национальном реестре , больше, чем в любом другом городе США. [22] [23] В Балтиморе 66 исторических районов Национального реестра и 33 местных исторических района. [22] Исторические записи правительства Балтимора находятся в Городском архиве Балтимора .

Район Балтимора был заселен коренными американцами по крайней мере с 10-го тысячелетия до нашей эры , когда палеоиндейцы впервые поселились в регионе. [24] В Балтиморе были обнаружены один палеоиндейский участок и несколько археологических памятников архаического периода и периода Вудленда , в том числе четыре из периода Позднего Вудленда . [24] В декабре 2021 года в парке Херринг-Ран на северо-востоке Балтимора было найдено несколько артефактов коренных американцев периода Вудленда, датируемых 5000–9000 лет назад. Находка последовала за периодом покоя археологических находок в городе Балтимор, который сохранялся с 1980-х годов. [25] В период Позднего Вудленда археологическая культура , известная как комплекс Потомак-Крик, проживала на территории от Балтимора на юг до реки Раппаханнок в современной Вирджинии . [26]

Город назван в честь Сесила Калверта, 2-го барона Балтимора , [27] английского пэра, члена ирландской Палаты лордов и основателя провинции Мэриленд . [28] [29] Калверты получили титул баронов Балтимор от поместья Балтимор , английского плантационного поместья, которое им было предоставлено в графстве Лонгфорд , Ирландия . [29] [ 30] Балтимор — это англицизация ирландского названия Baile an Tí Mhóir , что означает «город большого дома». [29]

В начале 1600-х годов непосредственные окрестности Балтимора были малонаселены, если вообще были, коренными американцами. Район округа Балтимор к северу использовался в качестве охотничьих угодий племенем саскуэханнок, живущим в нижней долине реки Саскуэханна . Этот говорящий на ирокезском языке народ «контролировал все верхние притоки Чесапика», но «воздерживался от больших контактов с поухатанами в регионе Потомак » и на юге в Вирджинии. [31] Под давлением саскуэханнок, племя пискатауэй , говорящее на алгонкинском языке , оставалось далеко к югу от района Балтимора и населяло в основном северный берег реки Потомак в том, что сейчас является округами Чарльз и южным Принс-Джордж в прибрежных районах к югу от линии водопада . [32] [33] [34]

Европейская колонизация Мэриленда началась всерьез с прибытием торгового судна «Ковчег» со 140 колонистами на остров Святого Климента на реке Потомак 25 марта 1634 года. [35] Затем европейцы начали заселять территорию дальше на север, в то место, где сейчас находится округ Балтимор . [36] Поскольку Мэриленд был колонией, улицы Балтимора были названы в знак лояльности к метрополии, например, улицы Кинг, Куин, Кинг-Джордж и Кэролайн. [37] Первоначальный административный центр округа , известный сегодня как Старый Балтимор, находился на реке Буш на территории современного Абердинского испытательного полигона . [38] [39] [40] Колонисты время от времени воевали с саскуэханноками, численность которых сокращалась в основном из-за новых инфекционных заболеваний, таких как оспа , эндемичных среди европейцев. [36] В 1661 году Дэвид Джонс заявил права на территорию, известную сегодня как Джонстаун , на восточном берегу ручья Джонс-Фолс . [41]

Колониальная Генеральная Ассамблея Мэриленда создала порт Балтимор в старом Уэтстоун-Пойнт, теперь Локаст-Пойнт , в 1706 году для торговли табаком . Город Балтимор, на западной стороне водопада Джонс, был основан 8 августа 1729 года, когда губернатор Мэриленда подписал акт, разрешающий «строительство города на северной стороне реки Патапско». Геодезисты начали планировать город 12 января 1730 года. К 1752 году в городе было всего 27 домов, включая церковь и две таверны. [37] Джонстаун и Феллс-Пойнт были заселены на востоке. Три поселения, занимающие 60 акров (24 га), стали коммерческим центром, а в 1768 году были назначены административным центром округа. [42]

Первый печатный станок был представлен городу в 1765 году Николасом Хассельбахом , чье оборудование впоследствии использовалось при печати первых газет Балтимора, The Maryland Journal и The Baltimore Advertiser , впервые опубликованных Уильямом Годдардом в 1773 году. [43] [44] [45]

Балтимор быстро рос в 18 веке, его плантации производили зерно и табак для колоний, производящих сахар в Карибском море . Прибыль от сахара поощряла выращивание тростника в Карибском море и импорт продовольствия плантаторами там. [46] Поскольку Балтимор был административным центром округа, в 1768 году было построено здание суда, обслуживающее как город, так и округ. Его площадь была центром общественных собраний и дискуссий.

Балтимор создал свою систему общественного рынка в 1763 году. [47] Рынок Лексингтон , основанный в 1782 году, является одним из старейших непрерывно действующих общественных рынков в Соединенных Штатах на сегодняшний день. [48] Рынок Лексингтон также был центром работорговли. Порабощенные чернокожие люди продавались на многочисленных площадках в центре города, а объявления о продаже публиковались в The Baltimore Sun. [ 49] И табак, и сахарный тростник были трудоемкими культурами.

В 1774 году в Балтиморе была создана первая почтовая система в том месте, где впоследствии появились Соединенные Штаты, [50] и первая водопроводная компания, зарегистрированная в новой независимой стране, Baltimore Water Company, 1792 год. [51] [52]

Балтимор сыграл свою роль в Американской революции . Городские лидеры, такие как Джонатан Плауман-младший, заставили многих жителей сопротивляться британским налогам , а торговцы подписали соглашения об отказе от торговли с Великобританией. [53] Второй Континентальный конгресс заседал в доме Генри Файта с декабря 1776 года по февраль 1777 года, фактически сделав город столицей Соединенных Штатов в этот период. [54]

В 1796–1797 годах Балтимор, Джонстаун и Феллс-Пойнт были включены в состав города Балтимор.

Город оставался частью окружающего округа Балтимор и продолжал служить его административным центром с 1768 по 1851 год, после чего стал независимым городом . [57]

Битва при Балтиморе против британцев в 1814 году вдохновила на создание национального гимна США « Знамя, усыпанное звездами », и на строительство Памятника битве , который стал официальной эмблемой города. Начала формироваться самобытная местная культура, и развился уникальный горизонт, усеянный церквями и памятниками. Балтимор получил свое прозвище «Город монументов» после визита в 1827 году президента Джона Куинси Адамса . На вечернем приеме Адамс произнес следующий тост: «Балтимор: город монументов — пусть дни его безопасности будут такими же процветающими и счастливыми, какими были дни его опасностей, мучительными и триумфальными». [58] [59]

Балтимор был пионером в использовании газового освещения в 1816 году, и его население быстро росло в последующие десятилетия с сопутствующим развитием культуры и инфраструктуры. Строительство финансируемой федеральным правительством Национальной дороги , которая позже стала частью US Route 40 , и частной железной дороги Балтимор и Огайо (B. & O.) сделали Балтимор крупным судоходным и производственным центром, связав город с основными рынками на Среднем Западе . К 1820 году его население достигло 60 000 человек, а его экономика переместилась с табачных плантаций на лесопиление , судостроение и текстильное производство. Эти отрасли промышленности выиграли от войны, но успешно перешли на развитие инфраструктуры в мирное время. [60]

В 1835 году в Балтиморе произошел один из самых страшных беспорядков на довоенном Юге , когда неудачные инвестиции привели к банковскому бунту в Балтиморе . [61] Именно эти беспорядки привели к тому, что город прозвали «городом мафии». [62] Вскоре после этого в городе был создан первый в мире стоматологический колледж — Балтиморский колледж стоматологической хирургии — в 1840 году, а в 1844 году была проведена первая в мире телеграфная линия между Балтимором и Вашингтоном, округ Колумбия .

Мэриленд, рабовладельческий штат с ограниченной народной поддержкой отделения , особенно в трех округах Южного Мэриленда, оставался частью Союза во время Гражданской войны в США после того, как Генеральная Ассамблея Мэриленда проголосовала 55–12 против отделения. Позже, стратегическая оккупация города Союзом в 1861 году гарантировала, что Мэриленд больше не будет рассматривать отделение. [63] [64] Столица Союза Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, была хорошо расположена, чтобы препятствовать сообщению или торговле Балтимора и Мэриленда с Конфедерацией . Балтимор понес некоторые из первых потерь Гражданской войны 19 апреля 1861 года, когда солдаты армии Союза по пути от Президент-стрит-стейшн до Кэмден-ярдс столкнулись с толпой сепаратистов во время беспорядков на Пратт-стрит .

В разгар Длительной депрессии , последовавшей за паникой 1873 года , компания Baltimore and Ohio Railroad попыталась снизить заработную плату своим рабочим, что привело к забастовкам и беспорядкам в городе и за его пределами . Забастовщики столкнулись с Национальной гвардией , в результате чего 10 человек погибли и 25 получили ранения. [65] Начало работы по переселению в Балтиморе было положено в начале 1893 года, когда преподобный Эдвард А. Лоуренс поселился у своего друга Фрэнка Томпсона в одном из доходных домов Винанса , вскоре после этого по адресу 814-816 West Lombard Street был основан Lawrence House . [66] [67]

7 февраля 1904 года Великий пожар в Балтиморе уничтожил более 1500 зданий за 30 часов, оставив более 70 кварталов в центре города сгоревшими дотла. Ущерб был оценен в 150 миллионов долларов в долларах 1904 года. [68] По мере того, как город восстанавливался в течение следующих двух лет, уроки, извлеченные из пожара, привели к улучшению стандартов противопожарного оборудования. [69]

Балтиморский юрист Милтон Дэшил выступал за постановление, запрещающее афроамериканцам переезжать в район Юто-Плейс на северо-западе Балтимора. Он предложил признать большинство белых жилых кварталов и большинство черных жилых кварталов и запретить людям переезжать в жилье в таких кварталах, где они будут меньшинством. Совет Балтимора принял постановление, и оно стало законом 20 декабря 1910 года с подписью мэра-демократа Дж. Барри Махула . [70] Постановление о сегрегации в Балтиморе было первым в своем роде в Соединенных Штатах. Многие другие южные города последовали его примеру, приняв свои собственные постановления о сегрегации, хотя Верховный суд США вынес решение против них в деле Бьюкенен против Уорли (1917). [71]

Город рос в площади за счет присоединения новых пригородов из соседних округов до 1918 года, когда город приобрел части округа Балтимор и округа Энн-Арандел . [72] Поправка к конституции штата, одобренная в 1948 году, требовала специального голосования граждан в любой предлагаемой области присоединения, что фактически предотвращало любое будущее расширение границ города. [73] Трамваи способствовали развитию отдаленных районов, таких как деревня Эдмонсон , жители которой могли легко добираться на работу в центр города. [74]

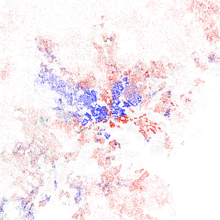

Под влиянием миграции с дальнего Юга и пригородной жизни белых относительная численность черного населения города выросла с 23,8% в 1950 году до 46,4% в 1970 году. [75] Воодушевленные методами блокбастера в сфере недвижимости , недавно заселенные белые районы быстро превратились в полностью черные кварталы, и к 1970 году этот процесс стал почти тотальным. [76]

Балтиморский бунт 1968 года , совпавший с восстаниями в других городах , последовал за убийством Мартина Лютера Кинга-младшего 4 апреля 1968 года. Общественный порядок не был восстановлен до 12 апреля 1968 года. Восстание в Балтиморе обошлось городу примерно в 10 миллионов долларов (88 миллионов долларов США в 2024 году). В общей сложности в город было направлено 12 000 солдат Национальной гвардии Мэриленда и федеральных войск. [77] Город снова столкнулся с проблемами в 1974 году, когда учителя, муниципальные служащие и полицейские провели забастовки. [78]

К началу 1970-х годов центр города Балтимор, известный как Внутренняя гавань, был заброшен и был занят скоплением заброшенных складов. Прозвище «Город очарования» появилось в 1975 году на встрече рекламодателей, стремящихся улучшить репутацию города. [79] [80] Усилия по перестройке района начались со строительства Мэрилендского научного центра , который открылся в 1976 году, Всемирного торгового центра Балтимора (1977) и Конференц-центра Балтимора (1979). Harborplace , городской торговый и ресторанный комплекс, открылся на набережной в 1980 году, за ним последовали Национальный аквариум , крупнейшее туристическое направление Мэриленда, и Музей промышленности Балтимора в 1981 году. В 1995 году город открыл Американский музей визионерского искусства на Федеральном холме. Во время эпидемии ВИЧ/СПИДа в Соединенных Штатах , сотрудник Департамента здравоохранения города Балтимор Роберт Мель убедил мэра города сформировать комитет для решения продовольственных проблем. Благотворительная организация Moveable Feast, базирующаяся в Балтиморе , выросла из этой инициативы в 1990 году. [81] [82] [83]

В 1992 году бейсбольная команда Baltimore Orioles переехала со стадиона Memorial Stadium в Oriole Park at Camden Yards , расположенный в центре города недалеко от гавани. Папа Иоанн Павел II провел мессу под открытым небом в Camden Yards во время своего папского визита в Соединенные Штаты в октябре 1995 года. Три года спустя футбольная команда Baltimore Ravens переехала на стадион M&T Bank Stadium рядом с Camden Yards. [84]

В Балтиморе на протяжении нескольких десятилетий наблюдался высокий уровень убийств , пик которого пришелся на 1993 год, а затем на 2015 год. [85] [86] Эти смерти особенно тяжело сказались на чернокожем сообществе. [87] После смерти Фредди Грея в апреле 2015 года в городе прошли крупные протесты , которые привлекли внимание международных СМИ, а также произошло столкновение между местной молодежью и полицией, в результате которого было объявлено чрезвычайное положение и введен комендантский час. [88]

В Балтиморе в 2004 году был заново открыт театр «Ипподром» [89] , в 2005 году — Музей истории и культуры афроамериканцев Мэриленда имени Реджинальда Ф. Льюиса , а в 2012 году был основан Национальный славянский музей . 12 апреля 2012 года в Университете Джонса Хопкинса прошла церемония открытия в ознаменование завершения строительства одного из крупнейших медицинских комплексов США — больницы Джонса Хопкинса в Балтиморе, в которую входят Башня кардиоваскулярной и интенсивной терапии имени шейха Зайда и Детский центр имени Шарлотты Р. Блумберг. Мероприятие, состоявшееся у входа в здание площадью 1,6 миллиона квадратных футов стоимостью 1,1 миллиарда долларов, было посвящено многочисленным донорам, включая шейха Халифу бин Зайда Аль Нахайяна , первого президента Объединенных Арабских Эмиратов , и Майкла Блумберга [90] [91 ]

В сентябре 2016 года городской совет Балтимора одобрил сделку по облигациям на сумму 660 миллионов долларов для проекта реконструкции Port Covington стоимостью 5,5 миллиарда долларов , продвигаемого основателем Under Armour Кевином Планком и его компанией по недвижимости Sagamore Development. Port Covington превзошел разработку Harbor Point как крупнейшую сделку по финансированию с налоговым приростом в истории Балтимора и один из крупнейших проектов городской реконструкции в стране. [92] Развитие набережной, включающее новую штаб-квартиру Under Armour, а также магазины, жилье, офисы и производственные помещения, по прогнозам, создаст 26 500 постоянных рабочих мест с годовым экономическим эффектом в размере 4,3 миллиарда долларов. [93] Goldman Sachs инвестировал 233 миллиона долларов в проект реконструкции. [94]

.jpg/440px-Wreckage_from_Key_Bridge_Collapse_(240326-A-SE916-9511).jpg)

Ранним утром 26 марта 2024 года городской мост Фрэнсиса Скотта Ки длиной 1,6 мили (2,6 км) , который составлял юго-восточную часть кольцевой дороги Балтимора , был сбит контейнеровозом и полностью обрушился . Была начата крупная спасательная операция, в которой власти США пытались спасти людей из воды. [95] Восемь строителей, которые в то время работали на мосту, упали в реку Патапско . [96] Двое человек были спасены из воды, [97] а тела остальных шестерых были найдены к 7 мая. [98] Замена моста была оценена в мае 2024 года по стоимости, приближающейся к 2 миллиардам долларов, с окончанием осенью 2028 года. [99]

Балтимор находится в северо-центральной части Мэриленда на реке Патапско , недалеко от места ее впадения в Чесапикский залив . Город расположен на линии падения между плато Пидмонт и прибрежной равниной Атлантики , которая делит Балтимор на «нижний город» и «верхний город». Высота города колеблется от уровня моря в гавани до 480 футов (150 м) в северо-западном углу около Пимлико . [6]

По данным переписи 2010 года, общая площадь города составляет 92,1 квадратных миль (239 км 2 ), из которых 80,9 квадратных миль (210 км 2 ) — это суша и 11,1 квадратных миль (29 км 2 ) — вода. [100] Общая площадь города составляет 12,1 процента от общей площади.

Балтимор почти окружен округом Балтимор, но политически независим от него. Граничит с округом Энн-Арандел на юге.

В Балтиморе представлены образцы каждого периода архитектуры на протяжении более чем двух столетий, а также работы таких архитекторов, как Бенджамин Латроб , Джордж А. Фредерик , Джон Рассел Поуп , Мис ван дер Роэ и И. М. Пей .

Балтимор богат архитектурно значимыми зданиями в различных стилях. Балтиморская базилика (1806–1821) — неоклассический проект Бенджамина Латроба и один из старейших католических соборов в Соединенных Штатах. В 1813 году Роберт Кэри Лонг-старший построил для Рембрандта Пила первое значительное сооружение в Соединенных Штатах, спроектированное специально как музей. После реставрации теперь это Муниципальный музей Балтимора, или, как его еще называют, Музей Пила .

McKim Free School была основана и финансирована Джоном Маккимом. Здание было возведено его сыном Исааком в 1822 году по проекту Уильяма Говарда и Уильяма Смолла. Оно отражает народный интерес к Греции , когда страна обеспечивала свою независимость, и научный интерес к недавно опубликованным рисункам афинских древностей.

Башня Phoenix Shot Tower (1828), высотой 234,25 фута (71,40 м), была самым высоким зданием в Соединенных Штатах до времен Гражданской войны и является одним из немногих сохранившихся сооружений такого рода. [101] Она была построена без использования внешних лесов. Здание Sun Iron Building, спроектированное RC Hatfield в 1851 году, было первым зданием города с железным фасадом и послужило образцом для целого поколения зданий в центре города. Пресвитерианская церковь Brown Memorial , построенная в 1870 году в память о финансисте Джордже Брауне , имеет витражи работы Луиса Комфорта Тиффани и была названа журналом Baltimore «одним из самых значительных зданий в этом городе, сокровищем искусства и архитектуры» . [102] [103]

Синагога на Ллойд-стрит, построенная в стиле греческого возрождения в 1845 году, является одной из старейших синагог в Соединенных Штатах . Больница Джонса Хопкинса , спроектированная подполковником Джоном С. Биллингсом в 1876 году, была значительным достижением своего времени в функциональном устройстве и противопожарной защите.

Всемирный торговый центр Пэя Им (1977) — самое высокое в мире равностороннее пятиугольное здание высотой 405 футов (123 м).

В районе Харбор-Ист завершилось строительство двух новых башен: 24-этажной башни, которая стала новой всемирной штаб-квартирой Legg Mason , и 21-этажного гостиничного комплекса Four Seasons .

Улицы Балтимора организованы в виде сетки и спицы, выложенной десятками тысяч рядных домов . Сочетание материалов на фасаде этих рядных домов также придает Балтимору его особый облик. Рядные дома представляют собой смесь облицовки из кирпича и формового камня, последняя технология была запатентована в 1937 году Альбертом Найтом. Джон Уотерс охарактеризовал формовый камень как «полиэстер кирпича» в 30-минутном документальном фильме « Маленькие замки: феномен формового камня» . [104] В «Балтиморском рядном доме » Мэри Эллен Хейворд и Чарльз Белфур рассматривали рядный дом как архитектурную форму, определяющую Балтимор как «возможно, никакой другой американский город». [105] В середине 1790-х годов застройщики начали строить целые кварталы рядных домов в британском стиле, которые стали доминирующим типом домов города в начале 19 века. [106]

Oriole Park at Camden Yards — это бейсбольный парк Высшей лиги , который открылся в 1992 году и был построен как бейсбольный парк в стиле ретро . Наряду с Национальным аквариумом, Camden Yards помогли возродить район Inner Harbor из того, что когда-то было исключительно промышленным районом, полным ветхих складов, в оживленный коммерческий район с барами, ресторанами и торговыми точками.

После международного конкурса, Юридическая школа Университета Балтимора присудила немецкой фирме Behnisch Architekten 1-ю премию за ее проект, который был выбран для нового дома школы. После открытия здания в 2013 году проект получил дополнительные награды, включая Национальную премию ENR "Лучший из лучших". [107]

Недавно отреставрированный театр Everyman в Балтиморе был отмечен Baltimore Heritage на церемонии вручения наград за сохранение 2013 года в 2013 году. Everyman Theatre получит награду Adaptive Reuse and Compatible Design Award в рамках церемонии вручения наград Baltimore Heritage за сохранение исторического наследия 2013 года. Baltimore Heritage — некоммерческая организация по сохранению исторического наследия и архитектуры в Балтиморе, которая занимается сохранением и продвижением исторических зданий и кварталов Балтимора. [108]

Балтимор официально разделен на девять географических регионов: Северный, Северо-Восточный, Восточный, Юго-Восточный, Южный, Юго-Западный, Западный, Северо-Западный и Центральный, причем каждый район патрулируется соответствующим полицейским департаментом Балтимора . Межштатная автомагистраль 83 и Чарльз-стрит до Ганновер-стрит и шоссе Ричи служат разделительной линией с востока на запад, а Восточная авеню до трассы 40 — разделительной линией с севера на юг; однако Балтимор-стрит является разделительной линией с севера на юг для Почтовой службы США . [120]

Центральный Балтимор, первоначально называвшийся Мидл-Дистрикт, [121] простирается к северу от Внутренней гавани до края парка Друид-Хилл . Центр Балтимора в основном служил коммерческим районом с ограниченными возможностями для проживания; однако, в период с 2000 по 2010 год население центра города выросло на 130 процентов, поскольку старые коммерческие объекты были заменены жилой недвижимостью. [122] По-прежнему являясь главным коммерческим районом и деловым районом города, он включает в себя спортивные комплексы Балтимора: Oriole Park в Camden Yards , M&T Bank Stadium и Royal Farms Arena ; а также магазины и достопримечательности во Внутренней гавани: Harborplace , Baltimore Convention Center , National Aquarium , Maryland Science Center , Pier Six Pavilion и Power Plant Live . [120]

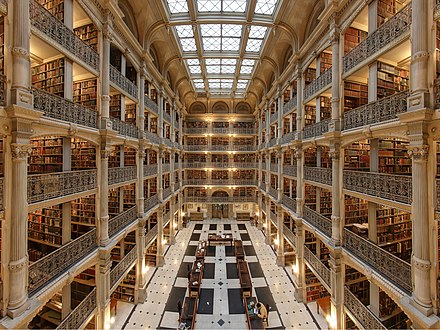

Университет Мэриленда, Балтимор , Медицинский центр Университета Мэриленда и рынок Лексингтон также находятся в центральном районе, как и Ипподром и множество ночных клубов, баров, ресторанов, торговых центров и различных других достопримечательностей. [120] [121] Северная часть Центрального Балтимора, между центром города и парком Друид-Хилл, является домом для многих культурных возможностей города. Колледж искусств Института Мэриленда , Институт Пибоди (музыкальная консерватория), Библиотека Джорджа Пибоди , Бесплатная библиотека Эноха Пратта – Центральная библиотека, Лирический оперный театр , Симфонический зал Джозефа Мейерхоффа , Художественный музей Уолтерса , Центр истории и культуры Мэриленда и его особняк Эноха Пратта , а также несколько галерей расположены в этом регионе. [123]

Несколько исторических и примечательных районов находятся в этом районе: Гованс (1755), Роланд Парк (1891), Гилфорд (1913), Хоумленд (1924), Хэмпден , Вудберри , Олд Гоучер (первоначальный кампус колледжа Гоучер ) и Джонс Фоллс . Вдоль коридора Йорк-роуд, идущего на север, находятся крупные районы Чарльз-Виллидж , Уэверли и Маунт-Вашингтон . Район искусств и развлечений Station North также расположен в Северном Балтиморе. [124]

Южный Балтимор, смешанный промышленный и жилой район, состоит из полуострова «Старый Южный Балтимор» ниже Внутренней гавани и к востоку от старых путей линии Камден железной дороги B&O и центра города Рассел-стрит . Это культурно, этнически и социально-экономически разнообразный прибрежный район с такими районами, как Локаст-Пойнт и Риверсайд вокруг большого парка с тем же названием. [125] К югу от Внутренней гавани, в историческом районе Федерал-Хилл , проживает множество работающих специалистов, есть пабы и рестораны. В конце полуострова находится исторический Форт Мак-Генри , национальный парк с конца Первой мировой войны, когда был снесен старый госпиталь армии США, окружавший звездообразные зубчатые стены 1798 года. [126]

За мостом Ганновер-стрит находятся жилые районы, такие как Черри-Хилл . [127]

Северо-Восток — это в первую очередь жилой район, где находится Университет штата Морган , ограниченный городской чертой 1919 года на северной и восточной границах, Синклер-лейн , Эрдман-авеню и шоссе Пуласки на юге и Аламедой на западе. Также в этом клине города на 33-й улице находится средняя школа Baltimore City College , третья старейшая действующая государственная средняя школа в Соединенных Штатах, основанная в центре города в 1839 году. [128] Напротив бульвара Лох-Рейвен находится бывшее место старого стадиона Memorial Stadium, домашнего стадиона Baltimore Colts , Baltimore Orioles и Baltimore Ravens , теперь замененного спортивным и жилым комплексом YMCA . [129] [130] Озеро Монтебелло находится на северо-востоке Балтимора. [121]

Расположенный ниже Синклер Лейн и Эрдман Авеню , выше Орлеан Стрит , Восточный Балтимор в основном состоит из жилых кварталов. В этой части Восточного Балтимора находятся Больница Джонса Хопкинса , Медицинская школа Университета Джонса Хопкинса и Детский центр Джонса Хопкинса на Бродвее . Известные кварталы включают: Armistead Gardens , Broadway East , Barclay , Ellwood Park , Greenmount и McElderry Park . [121]

В этом районе снимались фильмы « Убийство: Жизнь на улице» , «Угол» и «Прослушка» . [131]

Юго-восточный Балтимор, расположенный ниже улицы Файетт , граничащий с Внутренней гаванью и северо-западным рукавом реки Патапско на западе, городской чертой 1919 года на ее восточных границах и рекой Патапско на юге, представляет собой смешанный промышленный и жилой район. Паттерсон-парк , «лучший задний двор в Балтиморе», [132] а также район искусств Хайлендтаун и медицинский центр Джонса Хопкинса Bayview расположены в юго-восточном Балтиморе. Магазины в Кантон-Кроссинг открылись в 2013 году . [133] Район Кантон расположен вдоль главной набережной Балтимора. Другие исторические районы включают: Феллс-Пойнт , Паттерсон-Парк , Батчерс-Хилл , Хайлендтаун , Гриктаун , Харбор-Ист , Маленькая Италия и Аппер-Феллс-Пойнт . [121]

Северо-западный район ограничен границей округа на севере и западе, Gwynns Falls Parkway на юге и Pimlico Road на востоке, является домом для Pimlico Race Course , Sinai Hospital и штаб-квартиры NAACP . Его кварталы в основном жилые и разделены Northern Parkway . Район был центром еврейской общины Балтимора с момента окончания Второй мировой войны. Известные кварталы включают: Pimlico , Mount Washington , Cheswolde и Park Heights . [134]

Западный Балтимор находится к западу от центра города и бульвара Мартина Лютера Кинга-младшего и ограничен парковой зоной Гвиннс-Фоллс, авеню Фремонт и улицей Вест-Балтимор . Исторический район Олд-Уэст-Балтимор включает кварталы Гарлем-Парк , Сэндтаун-Винчестер , Друид-Хайтс , Мэдисон-Парк и Аптон . [135] [136] Первоначально преимущественно немецкий квартал, ко второй половине 19-го века Олд-Уэст-Балтимор стал домом для значительной части черного населения города. [135]

Он стал крупнейшим районом для черного сообщества города и его культурным, политическим и экономическим центром. [135] В этом районе расположены университет Коппина , торговый центр Mondawmin Mall и деревня Эдмондсон . Проблемы преступности в этом районе стали темой для телесериалов, таких как The Wire . [137] Местные организации, такие как Sandtown Habitat for Humanity и Upton Planning Committee, неуклонно преобразуют части ранее заброшенных районов Западного Балтимора в чистые, безопасные сообщества. [138] [139]

Юго-запад Балтимора ограничен линией округа Балтимор на западе, улицей Вест- Балтимор-стрит на севере и бульваром Мартина Лютера Кинга-младшего и улицей Рассел-стрит/Балтимор-Вашингтон-Парквэй (маршрут Мэриленд 295) на востоке. Известные районы в Юго-западном Балтиморе включают: Пигтаун , Кэрролтон-Ридж , Риджли-Делайт , Ликин-Парк , Вайолетвилл , Лейкленд и Моррелл-Парк . [121]

Больница Св. Агнес на авеню Уилкенс и Катон [121] расположена в этом районе, рядом с соседней средней школой Кардинала Гиббонса , которая является бывшим местом альма-матер Бейба Рута , промышленной школы Св. Марии. [ требуется ссылка ] Через этот участок Балтимора проходило начало исторической Национальной дороги , которая была построена в 1806 году вдоль Олд Фредерик-роуд и продолжалась в округе по Фредерик-роуд в Элликотт-Сити, штат Мэриленд . [ требуется ссылка ] Другие стороны в этом районе: Кэрролл-парк , один из крупнейших парков города, колониальный особняк Маунт-Клэр и бульвар Вашингтон , который датируется довоенными днями как главный маршрут из города в Александрию, Вирджиния , и Джорджтаун на реке Потомак . [ требуется ссылка ]

Балтимор граничит со следующими населенными пунктами, все из которых не являются корпоративными и имеют статус переписных местностей .

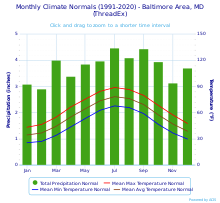

В Балтиморе влажный субтропический климат ( Cfa ) по классификации климата Кёппена , с жарким летом, прохладной зимой и летним пиком годовых осадков. [140] [141] Балтимор входит в зоны морозостойкости растений USDA 7b и 8a. [142] Лето обычно теплое, с редкими грозами в конце дня. Июль, самый теплый месяц, имеет среднюю температуру 80,3 °F (26,8 °C). Зимы варьируются от прохладных до мягких, но различаются, со спорадическими снегопадами: в январе дневное среднее значение составляет 35,8 °F (2,1 °C), [143] хотя температура довольно часто достигает 50 °F (10 °C) и иногда может опускаться ниже 20 °F (−7 °C), когда арктические воздушные массы влияют на этот район. [143] По данным Vox , зимы теплеют быстрее, чем лето. [141]

Весна и осень мягкие, причем весна является самым дождливым сезоном с точки зрения количества дней с осадками. Лето жаркое и влажное, среднесуточная температура в июле составляет 80,7 °F (27,1 °C). [143] Сочетание жары и влажности приводит к периодическим грозам. Юго-восточный бриз залива Чесапик часто возникает летом после обеда, когда горячий воздух поднимается над внутренними районами. Преобладающие ветры с юго-запада, взаимодействующие с этим бризом, а также с городским UHI, могут серьезно ухудшить качество воздуха. [144] [145] В конце лета и начале осени следы ураганов или их остатков могут вызвать наводнение в центре Балтимора, несмотря на то, что город находится далеко от типичных прибрежных зон штормовых нагонов . [146]

Среднее количество сезонных снегопадов составляет 19 дюймов (48 см). [147] Оно сильно варьируется в зависимости от года, в некоторые сезоны наблюдаются только следовые скопления снега, в то время как в другие наблюдаются несколько крупных северо-восточных штормов . [c] Из-за уменьшенного городского острова тепла (UHI) по сравнению с городом и расстояния от смягчающего Чесапикского залива, отдаленные и внутренние части метрополии Балтимора обычно прохладнее, особенно ночью, чем город и прибрежные города. Таким образом, в северных и западных пригородах зимний снегопад более значителен, и в некоторых районах в среднем выпадает более 30 дюймов (76 см) снега за зиму. [149]

Не редкость, когда линия дождя-снега устанавливается в районе метро. [150] Замерзающий дождь и мокрый снег случаются несколько раз в некоторые зимы в этом районе, так как теплый воздух перекрывает холодный воздух в нижних и средних слоях атмосферы. Когда ветер дует с востока, холодный воздух задерживается горами на западе, и в результате получается замерзающий дождь или мокрый снег.

Как и весь Мэриленд , Балтимор подвержен риску усиления последствий изменения климата . Исторически наводнения разрушали дома и почти убивали людей, особенно в районах с низким доходом, где большинство составляют чернокожие, а также вызывали засоры канализации, учитывая существующую неисправность системы водоснабжения Балтимора. [151]

Экстремальные температуры колеблются от −7 °F (−22 °C) 9 февраля 1934 года и 10 февраля 1899 года [ d] до 108 °F (42 °C) 22 июля 2011 года. [152] [153] В среднем температура 100 °F (38 °C) или выше наблюдается три дня в году, 90 °F (32 °C) или выше — 43 дня, и есть девять дней, когда максимальная температура не достигает отметки замерзания. [143]

Просмотр и редактирование необработанных графических данных.

Балтимор достиг пика численности населения в 949 708 человек по переписи населения США 1950 года. В каждой десятилетней переписи с тех пор город терял население, и по переписи 2020 года население города составило 585 708 человек. В 2011 году тогдашний мэр Стефани Роулингс-Блейк заявила, что одной из ее целей было увеличение населения города за счет улучшения городских услуг для сокращения числа людей, покидающих город, и принятия законодательства, защищающего права иммигрантов, для стимулирования роста. [163] Балтимор определен как город-убежище . [164] В 2019 году тогдашний мэр Джек Янг заявил, что Балтимор не будет помогать агентам ICE в иммиграционных рейдах. [165]

Население города Балтимор сократилось с 620 961 в 2010 году до 585 708 в 2020 году, что составляет падение на 5,7%. В 2020 году Балтимор потерял больше населения, чем любой другой крупный город в Соединенных Штатах . [166] [7] [167]

Джентрификация увеличилась после переписи 2000 года, в первую очередь в Восточном Балтиморе, центре города и Центральном Балтиморе, при этом 14,8% переписных участков имели рост доходов и повышение стоимости домов по темпам, превышающим темпы роста по городу в целом. Многие, но не все, джентрифицируемые кварталы являются преимущественно белыми районами, в которых произошел переход от домохозяйств с низким доходом к домохозяйствам с высоким доходом. Эти районы представляют собой либо расширение существующих джентрифицированных районов, либо активность вокруг Внутренней гавани, центра города или кампуса Хоумвуд Университета Джонса Хопкинса. [168] В некоторых районах в Восточном Балтиморе испаноязычное население увеличилось, в то время как как неиспаноязычное белое, так и неиспаноязычное черное население сократилось. [169]

После Нью-Йорка Балтимор был вторым городом в Соединенных Штатах, население которого достигло 100 000 человек. [170] [171] Согласно переписям населения США 1820–1850 годов, Балтимор был вторым по численности населения городом, [171] [172] прежде чем в 1860 году его обогнали Филадельфия и тогдашний независимый Бруклин , а затем в 1870 году его обошли Сент-Луис и Чикаго . [173] Балтимор входил в десятку городов с наибольшим населением в Соединенных Штатах по данным каждой переписи вплоть до переписи 1980 года. [174] После Второй мировой войны население Балтимора приближалось к 1 миллиону человек, пока после переписи 1950 года население не начало сокращаться.

По данным переписи 2010 года [update], население Балтимора составляло 63,7% чёрных , 29,6% белых (6,9% немцев , 5,8% итальянцев , 4% ирландцев , 2% американцев , 2% поляков , 0,5% греков ), 2,3% азиатов (0,54% корейцев , 0,46 % индийцев , 0,37% китайцев , 0,36% филиппинцев , 0,21% непальцев , 0,16% пакистанцев ) и 0,4% коренных американцев и коренных жителей Аляски. По расам 4,2% населения имеют испаноязычное, латиноамериканское или испанское происхождение (1,63% сальвадорцев , 1,21% мексиканцев , 0,63% пуэрториканцев , 0,6% гондурасцев ). [15]

Согласно переписи 2020 года, 8,1% жителей в период с 2016 по 2020 год были лицами иностранного происхождения. [175] Женщины составляли 53,4% населения. Средний возраст составлял 35 лет, 22,4% были моложе 18 лет, 65,8% — от 18 до 64 лет и 11,8% — 65 лет и старше. [15]

В Балтиморе проживает большое количество выходцев с Карибских островов , самые крупные группы — ямайцы и тринидадцы . Ямайская община Балтимора в основном сосредоточена в районе Парк-Хайтс , но поколения иммигрантов также жили в юго-восточном Балтиморе. [181]

В 2005 году около 30 778 человек (6,5%) идентифицировали себя как геи, лесбиянки или бисексуалы . [182] В 2012 году однополые браки в Мэриленде были легализованы, вступив в силу 1 января 2013 года. [183]

В период с 2016 по 2020 год средний доход домохозяйства составил 52 164 доллара США, а средний доход на душу населения — 32 699 долларов США по сравнению со средними показателями по стране в 64 994 доллара США и 35 384 доллара США соответственно. [175] В 2009 году средний доход домохозяйства составил 42 241 доллар США, а средний доход на душу населения — 25 707 долларов США по сравнению со средними показателями по стране в 53 889 долларов США на домохозяйство и 28 930 долларов США на душу населения. [15]

В 2009 году 23,7% населения жили за чертой бедности, по сравнению с 13,5% по стране в целом. [15] По данным переписи 2020 года, 20% жителей Балтимора жили в бедности, по сравнению с 11,6% по стране в целом. [175]

Жилье в Балтиморе относительно недорогое для крупных прибрежных городов такого размера. Медианная цена продажи домов в Балтиморе по состоянию на декабрь 2022 года составила $209 000, что выше $95 000 в 2012 году. [184] [185] Несмотря на обвал цен на жилье в конце 2000-х годов и наряду с общенациональными тенденциями, жители Балтимора по-прежнему сталкиваются с медленным ростом арендной платы, которая выросла на 3% летом 2010 года. [186] Медианная стоимость жилых единиц, занимаемых владельцами, в период с 2016 по 2020 год составила $242 499. [175]

Число бездомных в Балтиморе неуклонно растет. В 2011 году оно превысило 4000 человек. Особенно резко возросло число молодых бездомных. [187]

В 2015 году продолжительность жизни в Балтиморе составляла от 74 до 75 лет, по сравнению со средним показателем в США от 78 до 80 лет. В четырнадцати районах продолжительность жизни была ниже, чем в Северной Корее . Продолжительность жизни в центре города/Сетон-Хилл была сопоставима с Йеменом . [188]

В 2015 году 25% взрослых в Балтиморе сообщили о своей принадлежности к какой-либо религии. 50% взрослого населения Балтимора являются протестантами . [h] Католицизм является второй по величине религиозной принадлежностью, составляя 15% процентов населения, за ним следуют иудаизм (3%) и ислам (2%). Около 1% идентифицируют себя с другими христианскими конфессиями . [189] [190] [191]

В 2010 году 91% (526 705) жителей Балтимора в возрасте от пяти лет и старше говорили дома только по-английски. Около 4% (21 661) говорили по-испански. На других языках, таких как африканские языки , французский и китайский, говорят менее 1% населения. [192]

Когда-то Балтимор был преимущественно промышленным городом, с экономической базой, сосредоточенной на обработке стали, судоходстве, производстве автомобилей (General Motors Baltimore Assembly ) и транспорте, но затем он пережил деиндустриализацию , которая стоила жителям десятков тысяч низкоквалифицированных, высокооплачиваемых рабочих мест. [193] Теперь Балтимор полагается на низкооплачиваемую экономику услуг , которая составляет 31% рабочих мест в городе. [194] [195] На рубеже 20-го века Балтимор был ведущим производителем ржаного виски и соломенных шляп в США . Он лидировал в переработке сырой нефти, поставляемой в город по трубопроводу из Пенсильвании. [196] [197] [198]

В марте 2018 года уровень безработицы в Балтиморе составлял 5,8%. [199] В 2012 году четверть жителей Балтимора и 37% детей Балтимора жили в бедности. [200] Ожидается, что закрытие в 2012 году крупного сталелитейного завода в Спэрроуз-Пойнт окажет дальнейшее влияние на занятость и местную экономику. [201] В 2013 году 207 000 рабочих ежедневно ездили в Балтимор. [202] Центр Балтимора является основным экономическим активом в городе Балтимор и регионе с 29,1 миллионами квадратных футов офисных помещений. Технологический сектор быстро растет, так как метрополитен Балтимора занимает 8-е место в отчете CBRE Tech Talent Report среди 50 городских агломераций США по высоким темпам роста и количеству технических специалистов. [203] В 2013 году Forbes поставил Балтимор на четвертое место среди «новых технологических горячих точек» Америки. [204]

В городе находится больница имени Джона Хопкинса . Другие крупные компании в Балтиморе включают Under Armour , [205] BRT Laboratories , Cordish Company , [206] Legg Mason , McCormick & Company , T. Rowe Price и Royal Farms . [207] Сахарный завод, принадлежащий American Sugar Refining, является одним из культурных символов Балтимора. Некоммерческие организации, базирующиеся в Балтиморе, включают Lutheran Services in America и Catholic Relief Services .

По состоянию на середину 2013 года почти четверть рабочих мест в регионе Балтимор были в сфере науки, технологий, инженерии и математики, что отчасти объясняется обширной сетью школ бакалавриата и магистратуры города; в это число были включены специалисты по техническому обслуживанию и ремонту. [208]

Центром международной торговли региона является Всемирный торговый центр Балтимора . Здесь размещаются администрация порта Мэриленд и штаб-квартира основных судоходных линий США. Балтимор занимает 9-е место по общей стоимости грузов в долларах США и 13-е место по тоннажу грузов среди всех портов США. В 2014 году общий объем грузов, проходящих через порт, составил 29,5 млн тонн, что меньше, чем 30,3 млн тонн в 2013 году. Стоимость грузов, проходящих через порт в 2014 году, составила 52,5 млрд долларов США, что меньше, чем 52,6 млрд долларов США в 2013 году. Порт Балтимора генерирует 3 млрд долларов США в виде ежегодной заработной платы и окладов, а также поддерживает 14 630 прямых рабочих мест и 108 000 рабочих мест, связанных с работой порта. В 2014 году порт собрал более 300 млн долларов США в виде налогов. [209]

Порт обслуживает более 50 океанских перевозчиков, совершая около 1800 ежегодных визитов. Среди всех портов США Балтимор занимает первое место по обработке автомобилей, легких грузовиков, сельскохозяйственной и строительной техники; а также импортируемой лесной продукции, алюминия и сахара. Порт занимает второе место по экспорту угля. Круизная индустрия порта Балтимора, которая предлагает круглогодичные поездки по нескольким линиям, поддерживает более 500 рабочих мест и приносит более 90 миллионов долларов в экономику Мэриленда ежегодно. Рост в порту продолжается, поскольку администрация порта Мэриленда планирует превратить южную оконечность бывшего сталелитейного завода в морской терминал, в первую очередь для поставок автомобилей и грузовиков, а также для ожидаемого нового бизнеса в Балтиморе после завершения проекта расширения Панамского канала . [209]

История и достопримечательности Балтимора сделали его популярным туристическим направлением. В 2014 году город посетили 24,5 миллиона человек, которые потратили 5,2 миллиарда долларов. [210] Центр для посетителей Балтимора, которым управляет Visit Baltimore , расположен на улице Лайт-стрит во Внутренней гавани. Большая часть городского туризма сосредоточена вокруг Внутренней гавани, а Национальный аквариум является главным туристическим направлением Мэриленда. Реставрация Балтиморской гавани сделала ее «городом лодок», где выставлены на обозрение и открыты для публики несколько исторических кораблей и других достопримечательностей. USS Constellation , последнее судно времен Гражданской войны на плаву, пришвартовано в начале Внутренней гавани; USS Torsk , подводная лодка, которая удерживает рекорд ВМС по погружениям (более 10 000); и катер береговой охраны WHEC-37 , последний уцелевший военный корабль США, находившийся в Перл-Харборе во время японского нападения 7 декабря 1941 года, и который вступил в бой с японскими самолетами «Зеро» во время боя. [211]

Также пришвартован плавучий маяк Chesapeake , который десятилетиями обозначал вход в Чесапикский залив; и маяк Seven Foot Knoll, старейший сохранившийся маяк с винтовыми сваями в Чесапикском заливе, который когда-то обозначал устье реки Патапско и вход в Балтимор. Все эти достопримечательности принадлежат и обслуживаются организацией Historic Ships in Baltimore . Внутренняя гавань также является портом приписки Pride of Baltimore II , судна «посла доброй воли» штата Мэриленд, реконструкции знаменитого судна Baltimore Clipper . [211]

Другие туристические направления включают спортивные площадки, такие как Oriole Park at Camden Yards , M&T Bank Stadium и Pimlico Race Course , Fort McHenry , районы Mount Vernon , Federal Hill и Fells Point , рынок Лексингтон , казино Horseshoe , а также музеи, такие как Музей искусств Уолтерса , Музей промышленности Балтимора , Дом и музей Бейба Рута , Научный центр Мэриленда и Железнодорожный музей B&O .

Балтимор исторически был рабочим портовым городом, иногда его называли «городом кварталов». Он состоит из 72 обозначенных исторических районов [212], традиционно населенных различными этническими группами. Сегодня наиболее примечательными являются три района в центре города вдоль порта: Внутренняя гавань, часто посещаемая туристами из-за ее отелей, магазинов и музеев; Феллс-Пойнт, когда-то любимое место развлечений для моряков, но теперь отремонтированное и облагороженное (и показанное в фильме « Неспящие в Сиэтле» ); и Маленькая Италия , расположенная между двумя другими, где базируется итало-американская община Балтимора — и где выросла спикер Палаты представителей США Нэнси Пелоси .

Further inland, Mount Vernon is the traditional center of cultural and artistic life of the city. It is home to a distinctive Washington Monument, set atop a hill in a 19th-century urban square, that predates the monument in Washington, D.C. by several decades. Baltimore has a significant German American population,[213] and was the second-largest port of immigration to the United States behind Ellis Island in New York and New Jersey. Between 1820 and 1989, almost 2 million who were German, Polish, English, Irish, Russian, Lithuanian, French, Ukrainian, Czech, Greek and Italian came to Baltimore, mostly between 1861 and 1930. By 1913, when Baltimore was averaging forty thousand immigrants per year, World War I closed off the flow of immigrants. By 1970, Baltimore's heyday as an immigration center was a distant memory. There was a Chinatown dating back to at least the 1880s, which consisted of 400 Chinese residents. A local Chinese-American association remains based there, with one Chinese restaurant as of 2009.

Beer making thrived in Baltimore from the 1800s to the 1950s, with over 100 old breweries in the city's past.[214] The best remaining example of that history is the old American Brewery Building on North Gay Street and the National Brewing Company building in the Brewer's Hill neighborhood. In the 1940s the National Brewing Company introduced the nation's first six-pack. National's two most prominent brands, were National Bohemian Beer colloquially "Natty Boh" and Colt 45. Listed on the Pabst website as a "Fun Fact", Colt 45 was named after running back #45 Jerry Hill of the 1963 Baltimore Colts and not the .45 caliber handgun ammunition round. Both brands are still made today, albeit outside of Maryland, and served all around the Baltimore area at bars, as well as Orioles and Ravens games.[215] The Natty Boh logo appears on all cans, bottles, and packaging. Merchandise featuring him can be found in shops in Maryland, including several in Fells Point.

Each year the Artscape takes place in the city in the Bolton Hill neighborhood, close to the Maryland Institute College of Art. Artscape styles itself as the "largest free arts festival in America".[citation needed] Each May, the Maryland Film Festival takes place in Baltimore, using all five screens of the historic Charles Theatre as its anchor venue. Many movies and television shows have been filmed in Baltimore. Homicide: Life on the Street was set and filmed in Baltimore, as well as The Wire. House of Cards and Veep are set in Washington, D.C. but filmed in Baltimore.[216]

Baltimore has cultural museums in many areas of study. The Baltimore Museum of Art and the Walters Art Museum are internationally renowned for their collections of art. The Baltimore Museum of Art has the largest holding of works by Henri Matisse in the world.[217] The American Visionary Art Museum has been designated by Congress as America's national museum for visionary art.[218] The National Great Blacks In Wax Museum is the first African American wax museum in the country, featuring more than 150 life-size and lifelike wax figures.[51]

Baltimore is known for its Maryland blue crabs, crab cake, Old Bay Seasoning, pit beef, and the "chicken box". The city has many restaurants in or around the Inner Harbor. The most known and acclaimed are the Charleston, Woodberry Kitchen, and the Charm City Cakes bakery featured on the Food Network's Ace of Cakes. The Little Italy neighborhood's biggest draw is the food. Fells Point also is a foodie neighborhood for tourists and locals and is where the oldest continuously running tavern in the country, "The Horse You Came in on Saloon", is located.[219]

Many of Baltimore's upscale restaurants are found in Harbor East. Five public markets are located across Baltimore. The Baltimore Public Market System is the oldest continuously operating public market system in the United States.[220] Lexington Market is one of the longest-running markets in the world and the longest running in the country, having been around since 1782. The market continues to stand at its original site. Baltimore is the last place in America where one can still find arabbers, vendors who sell fresh fruits and vegetables from a horse-drawn cart that goes up and down neighborhood streets.[221] Food- and drink-rating site Zagat ranked Baltimore second in a list of the 17 best food cities in the US in 2015.[222]

Baltimore city, along with its surrounding regions, is home to a unique local dialect known as the Baltimore dialect. It is part of the larger Mid-Atlantic American English group and is noted to be very similar to the Philadelphia dialect.[223][224]

The so-called "Bawlmerese" accent is known for its characteristic pronunciation of its long "o" vowel, in which an "eh" sound is added before the long "o" sound (/oʊ/ shifts to [ɘʊ], or even [eʊ]).[225] It adopts Philadelphia's pattern of the short "a" sound, such that the tensed vowel in words like "bath" or "ask" does not match the more relaxed one in "sad" or "act".[223]

Baltimore native John Waters parodies the city and its dialect extensively in his films. Most are filmed in Baltimore, including the 1972 cult classic Pink Flamingos, as well as Hairspray and its Broadway musical remake.

Baltimore has four state-designated arts and entertainment districts: The Pennsylvania Avenue Black Arts and Entertainment District, Station North Arts and Entertainment District, Highlandtown Arts District, and the Bromo Arts & Entertainment District.[226][227][228]

The Baltimore Office of Promotion and The Arts, a non-profit organization, produces events and arts programs as well as managing several facilities. It is the official Baltimore City Arts Council. BOPA coordinates Baltimore's major events, including New Year's Eve and July 4 celebrations at the Inner Harbor, Artscape, which is America's largest free arts festival, Baltimore Book Festival, Baltimore Farmers' Market & Bazaar, School 33 Art Center's Open Studio Tour, and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Parade.[229]

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is an internationally renowned orchestra, founded in 1916 as a publicly funded municipal organization. Its most recent music director was Marin Alsop, a protégé of Leonard Bernstein's. Centerstage is the premier theater company in the city and a regionally well-respected group. The Lyric Opera House is the home of Lyric Opera Baltimore, which operates there as part of the Patricia and Arthur Modell Performing Arts Center. Shriver Hall Concert Series, founded in 1966, presents classical chamber music and recitals featuring nationally and internationally recognized artists.[230]

The Baltimore Consort has been a leading early music ensemble for over twenty-five years. The France-Merrick Performing Arts Center, home of the restored Thomas W. Lamb-designed Hippodrome Theatre, has afforded Baltimore the opportunity to become a major regional player in the area of touring Broadway and other performing arts presentations. Renovating Baltimore's historic theatres has become widespread throughout the city. Renovated theatres include the Everyman, Centre, Senator, and most recently Parkway Theatre. Other buildings have been reused. These include the former Mercantile Deposit and Trust Company bank building, which is now The Chesapeake Shakespeare Company Theater.

Baltimore has a wide array of professional (non-touring) and community theater groups. Aside from Center Stage, resident troupes in the city include The Vagabond Players, the oldest continuously operating community theater group in the country, Everyman Theatre, Single Carrot Theatre, and Baltimore Theatre Festival. Community theaters in the city include Fells Point Community Theatre and the Arena Players Inc., which is the nation's oldest continuously operating African American community theater.[231] In 2009, the Baltimore Rock Opera Society, an all-volunteer theatrical company, launched its first production.[232]

Baltimore is home to the Pride of Baltimore Chorus, a three-time international silver medalist women's chorus, affiliated with Sweet Adelines International. The Maryland State Boychoir is located in the northeastern Baltimore neighborhood of Mayfield.

Baltimore is the home of non-profit chamber music organization Vivre Musicale. VM won a 2011–2012 award for Adventurous Programming from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers and Chamber Music America.[233]

The Peabody Institute, located in the Mount Vernon neighborhood, is the oldest conservatory of music in the United States.[234] Established in 1857, it is one of the most prestigious in the world,[234] along with Juilliard, Eastman, and the Curtis Institute. The Morgan State University Choir is also one of the nation's most prestigious university choral ensembles.[235] The city is home to the Baltimore School for the Arts, a public high school in the Mount Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore. The institution is nationally recognized for its success in preparation for students entering music (vocal/instrumental), theatre (acting/theater production), dance, and visual arts.

In 1981, Baltimore hosted the first International Theater Festival, the first such festival in the country. Executive producer Al Kraizer staged 66 performances of nine shows by international theatre companies, including from Ireland, the United Kingdom, South Africa and Israel.[236] The festival proved to be expensive to mount, and in 1982 the festival was hosted in Denver, called the World Theatre Festival,[237] at the Denver Center for Performing Arts, after the city had asked Kraizer to organize it.[238]

In June 1986, the 20th Theatre of Nations, sponsored by the International Theatre Institute, was held in Baltimore, the first time it had been held in the U.S.[239]

Baltimore has a long and storied baseball history, including its distinction as the birthplace of Babe Ruth in 1895. The original 19th century Baltimore Orioles were one of the most successful early franchises, featuring numerous hall of famers during its years from 1882 to 1899. As one of the eight inaugural American League franchises, the Baltimore Orioles played in the AL during the 1901 and 1902 seasons. The team moved to New York City before the 1903 season and was renamed the New York Highlanders, which later became the New York Yankees. Ruth played for the minor league Baltimore Orioles team, which was active from 1903 to 1914. After playing one season in 1915 as the Richmond Climbers, the team returned the following year to Baltimore, where it played as the Orioles until 1953.[citation needed]

The team currently known as the Baltimore Orioles has represented Major League Baseball locally since 1954 when the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore. The Orioles advanced to the World Series in 1966, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1979 and 1983, winning three times (1966, 1970 and 1983), while making the playoffs all but one year (1972) from 1969 through 1974.[240]

In 1995, local player (and later Hall of Famer) Cal Ripken Jr. broke Lou Gehrig's streak of 2,130 consecutive games played, for which Ripken was named Sportsman of the Year by Sports Illustrated magazine.[citation needed] Six former Orioles players, including Ripken (2007), and two of the team's managers have been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Since 1992, the Orioles' home ballpark has been Oriole Park at Camden Yards, which has been hailed as one of the league's best since it opened.[241]

Prior to a National Football League team moving to Baltimore, there had been several attempts at a professional football team prior to the 1950s, which were blocked by the Washington team and its NFL friends. Most were minor league or semi-professional teams. The first major league to base a team in Baltimore was the All-America Football Conference (AAFC), which had a team named the Baltimore Colts. The AAFC Colts played for three seasons in the AAFC (1947, 1948, and 1949), and when the AAFC folded following the 1949 season, moved to the NFL for a single year (1950) before going bankrupt.

In 1953, the NFL's Dallas Texans folded. Its assets and player contracts were purchased by an ownership team headed by Baltimore businessman Carroll Rosenbloom, who moved the team to Baltimore, establishing a new team also named the Baltimore Colts. During the 1950s and 1960s, the Colts were one of the NFLs more successful franchises, led by Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Johnny Unitas who set a then-record of 47 consecutive games with a touchdown pass. The Colts advanced to the NFL Championship twice (1958 & 1959) and Super Bowl twice (1969 & 1971), winning all except Super Bowl III in 1969. After the 1983 season, the team left Baltimore for Indianapolis in 1984, where they became the Indianapolis Colts.

The NFL returned to Baltimore when the former Cleveland Browns moved to Baltimore to become the Baltimore Ravens in 1996. Since then, the Ravens won a Super Bowl championship in 2000 and 2012, seven AFC North division championships (2003, 2006, 2011, 2012, 2018, 2019 and 2023), and appeared in five AFC Championship Games (2000, 2008, 2011, 2012 and 2023).[242]

Baltimore also hosted a Canadian Football League franchise, the Baltimore Stallions for the 1994 and 1995 seasons. Following the 1995 season, and ultimate end to the Canadian Football League in the United States experiment, the team was sold and relocated to Montreal.

The first professional sports organization in the United States, The Maryland Jockey Club, was formed in Baltimore in 1743. Preakness Stakes, the second race in the United States Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing, has been held every May at Pimlico Race Course in Baltimore since 1873.

College lacrosse is a common sport in the spring, as the Johns Hopkins Blue Jays men's lacrosse team has won 44 national championships, the most of any program in history. In addition, Loyola University won its first men's NCAA lacrosse championship in 2012.

The Baltimore Blast are a professional arena soccer team that play in the Major Arena Soccer League at the SECU Arena on the campus of Towson University. The Blast have won nine championships in various leagues, including the MASL. A previous entity of the Blast played in the Major Indoor Soccer League from 1980 to 1992, winning one championship. The Baltimore Kings, a Baltimore Blast affiliate,[243] joined MASL 3 in 2021 to begin play in 2022.[244]

FC Baltimore 1729 was a semi-professional soccer club in the NPSL league, with the goal of bringing a community-oriented competitive soccer experience to Baltimore. Their inaugural season started on May 11, 2018, and they played their home games at CCBC Essex Field. Baltimore City F.C. is an Eastern Premier Soccer League club that plays since 2023 at Middle Branch Fitness Center in Cherry Hill.

The Baltimore Blues were a semi-professional rugby league club which began competition in the USA Rugby League in 2012.[245] The Baltimore Bohemians were an American soccer club which competed in the USL Premier Development League, the fourth tier of the American Soccer Pyramid. Their inaugural season started in the spring of 2012.

The Baltimore Grand Prix debuted along the streets of the Inner Harbor section of the city's downtown on September 2–4, 2011. The event played host to the American Le Mans Series on Saturday and the IndyCar Series on Sunday. Support races from smaller series were also held, including Indy Lights. After three consecutive years, on September 13, 2013, it was announced that the event would not be held in 2014 or 2015 due to scheduling conflicts.[246]

The athletic equipment company Under Armour is also based in Baltimore. Founded in 1996 by Kevin Plank, a University of Maryland alumnus, the company's headquarters are located in Tide Point, adjacent to Fort McHenry and the Domino Sugar factory. The Baltimore Marathon is the flagship race of several races. The marathon begins at Camden Yards and travels through many diverse neighborhoods of Baltimore, including the scenic Inner Harbor waterfront area, historic Federal Hill, Fells Point, and Canton, Baltimore. The race then proceeds to other important focal points of the city such as Patterson Park, Clifton Park, Lake Montebello, the Charles Village neighborhood, and the western edge of downtown. After winding through 42.195 kilometres (26.219 mi) of Baltimore, the race ends at virtually the same point at which it starts.

The Baltimore Brigade were an Arena Football League team based in Baltimore that, from 2017 to 2019, played at Royal Farms Arena. In 2019, the team ceased operations along with the rest of the league.

Baltimore has over 4,900 acres (1,983 ha) of parkland.[247] The Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks manages the majority of parks and recreational facilities in the city, including Patterson Park, Federal Hill Park, and Druid Hill Park.[248] The city is home to Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, a coastal star-shaped fort best known for its role in the War of 1812. As of 2015[update], The Trust for Public Land, a national land conservation organization, ranks Baltimore 40th among the 75-largest U.S. cities.[247]

Baltimore is an independent city, and not part of any county. For most governmental purposes under Maryland law, Baltimore City is treated as a county-level entity. The United States Census Bureau uses counties as the basic unit for presentation of statistical information in the United States, and treats Baltimore as a county equivalent for those purposes.

Baltimore has been a Democratic stronghold for over 150 years, with Democrats dominating every level of government. In virtually all elections, the Democratic primary is the real contest.[249] As of the 2020 elections, registered Democrats outnumbered registered Republicans by almost 10-to-1.[250] No Republican has been elected to the City Council since 1939. The city's last Republican mayor, Theodore McKeldin, left office in 1967. No Republican candidate since then has received 25 percent or more of the vote. In the 2016 and 2020 mayoral elections, the Republicans were pushed into third place by write-in and independent candidates, respectively. The last Republican candidate for president to win the city was Dwight Eisenhower in his successful reelection bid in 1956.

The city hosted the first six Democratic National Conventions, from 1832 through 1852, and hosted the DNC again in 1860, 1872, and 1912.[251]

Brandon Scott is the current mayor of Baltimore. He was elected in 2020 and took office on December 8, 2020.

Scott succeeded Jack Young, who took office on May 2, 2019. Young had been the president of the Baltimore City Council when Mayor Catherine Pugh was accused of a self-dealing book-sales arrangement. He became acting mayor on April 2 when she took a leave of absence, then mayor upon her resignation.[253][254]

Pugh, a Democrat, won the 2016 mayoral election with 57.1% of the vote and took office on December 6, 2016.[255]

Stephanie Rawlings-Blake assumed the office of Mayor on February 4, 2010, when predecessor Dixon's resignation became effective.[256] Rawlings-Blake had been serving as City Council President at the time. She was elected to a full term in 2011, defeating Pugh in the primary election and receiving 84% of the vote.[257]

Sheila Dixon became the first female mayor of Baltimore on January 17, 2007. As the former City Council President, she assumed the office of Mayor when former Mayor Martin O'Malley took office as Governor of Maryland.[258] On November 6, 2007, Dixon won the Baltimore mayoral election. Mayor Dixon's administration ended less than three years after her election, the result of a criminal investigation that began in 2006 while she was still City Council President. She was convicted on a single misdemeanor charge of embezzlement on December 1, 2009. A month later, Dixon made an Alford plea to a perjury charge and agreed to resign from office; Maryland, like most states, does not allow convicted felons to hold office.[259][260]

Grassroots pressure for reform, voiced as Question P, restructured the city council in November 2002, against the will of the mayor, the council president, and the majority of the council. A coalition of union and community groups, organized by the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), backed the effort.[261]

Baltimore City Council is made up of 14 single-member districts and one elected at-large council president.[262][263]

The Baltimore City Police Department is the current primary law enforcement agency serving Baltimore citizens. It was founded 1784 as a "Night City Watch" and day Constables system and later reorganized as a City Department in 1853, with a later reorganization under State of Maryland supervision in 1859, with appointments made by the Governor of Maryland after a period of civic and elections violence with riots in the later part of the decade. Campus and building security for the city's public schools is provided by the Baltimore City Public Schools Police, established in the 1970s.

In the four-year span of 2011 to 2015, 120 lawsuits were brought against Baltimore police for alleged brutality and misconduct. The Freddie Gray settlement of $6.4 million exceeds the combined total settlements of the 120 lawsuits, as state law caps such payments.[264]

Maryland Transportation Authority Police under the Maryland Department of Transportation, originally established as the "Baltimore Harbor Tunnel Police" when opened in 1957, is the primary law enforcement agency on the Fort McHenry Tunnel Thruway on I-95 and the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel Thruway, which goes underneath the northwestern branch of Patapsco River, and Interstate 395, which has three ramp bridges crossing the middle branch of the Patapsco River that are under MdTA jurisdiction, and have limited concurrent jurisdiction with the Baltimore Police Department under a memorandum of understanding.

Law enforcement on the fleet of transit buses and transit rail systems serving Baltimore is the responsibility of the Maryland Transit Administration Police, which is part of the Maryland Transit Administration of the state Department of Transportation. The MTA Police also share jurisdiction authority with the Baltimore City Police, governed by a memorandum of understanding.[265]

As the enforcement arm of the Baltimore circuit and district court system, the Baltimore City Sheriff's Office, created by state constitutional amendment in 1844, is responsible for the security of city courthouses and property, service of court-ordered writs, protective and peace orders, warrants, tax levies, prisoner transportation and traffic enforcement. Deputy Sheriffs are sworn law enforcement officials, with full arrest authority granted by the constitution of Maryland, the Maryland Police and Correctional Training Commission and the Sheriff of Baltimore.[266]

The United States Coast Guard, operating out of their shipyard and facility (since 1899) at Arundel Cove on Curtis Creek, (off Pennington Avenue extending to Hawkins Point Road/Fort Smallwood Road) in the Curtis Bay section of southern Baltimore City and adjacent northern Anne Arundel County. The U.S.C.G. also operates and maintains a presence on Baltimore and Maryland waterways in the Patapsco River and Chesapeake Bay. "Sector Baltimore" is responsible for commanding law enforcement and search & rescue units as well as aids to navigation.

_and_Franklintown_Road_in_Baltimore_City,_Maryland.jpg/440px-2016-05-11_18_45_30_Baltimore_City_Police_Car_at_the_intersection_of_Franklin_Street_(U.S._Route_40)_and_Franklintown_Road_in_Baltimore_City,_Maryland.jpg)

Baltimore is considered one of the most dangerous cities in the U.S.[267] Experts say an emerging gang presence and heavy recruitment of adolescent boys into these gangs, who are statistically more likely to get serious charges reduced or dropped, are major reasons for the sustained crime crises in the city.[268][269] Overall reported crime dropped by 60% from the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s, but homicides and gun violence remain high and far exceed the national average.[270]

The worst years for crime in Baltimore overall were from 1993 to 1996, with 96,243 crimes reported in 1995. Baltimore's 344 homicides in 2015 represented the highest homicide rate in the city's recorded history—52.5 per 100,000 people, surpassing the record ratio set in 1993—and the second-highest for U.S. cities behind St. Louis and ahead of Detroit. Of Baltimore's 344 homicides in 2015, 321 (93.3%) of the victims were African-American.[270]

Drug use and deaths by drug use, particularly drugs used intravenously, such as heroin, are a related problem which has impaired Baltimore for decades. Among cities greater than 400,000, Baltimore ranked 2nd in its opiate drug death rate in the United States. The DEA reported that 10% of Baltimore's population – about 64,000 people – are addicted to heroin, most of which is trafficked into the city from New York.[271][272][273][274][275]

In 2011, Baltimore police reported 196 homicides, the lowest number in the city since 197 homicides in 1978, and far lower than the peak homicide count of 353 slayings in 1993. City leaders at the time credited a sustained focus on repeat violent offenders and increased community engagement for the continued drop, reflecting a nationwide decline in crime.[276][277]

In August 2014, Baltimore's new youth curfew law went into effect. It prohibits unaccompanied children under age 14 from being on the streets after 9 p.m. and those aged 14–16 from being out after 10 p.m. during the week and 11 p.m. on weekends and during the summer. The goal is to keep children out of dangerous places and reduce crime.[278]

Crime in Baltimore reached another peak in 2015 when the year's tally of 344 homicides was second only to the record 353 in 1993, when Baltimore had about 100,000 more residents. The killings in 2015 were on pace with recent years in the early months of 2015, but skyrocketed after the unrest and rioting of late April following the killing of Freddie Gray by police. In five of the next eight months, killings topped 30–40 per month. Nearly 90 percent of 2015's homicides resulted from shootings, renewing calls for new gun laws. In 2016, there were 318 murders in the city.[279] This total marked a 7.56 percent decline in homicides from 2015.

In an interview with The Guardian on November 2, 2017,[280] David Simon, himself a former police reporter for The Baltimore Sun, ascribed the most recent surge in murders to the high-profile decision by Baltimore state's attorney, Marilyn Mosby, to charge six city police officers following the death of Freddie Gray after he was paralyzed during a "rough-ride" in a police van while in police custody in April 2015, dying from the injury a week later. "What Mosby basically did was send a message to the Baltimore police department: 'I'm going to put you in jail for making a bad arrest.' So officers figured it out: 'I can go to jail for making the wrong arrest, so I'm not getting out of my car to clear a corner,' and that's exactly what happened post-Freddie Gray."[280]

In Baltimore, "arrest numbers have plummeted from more than 40,000 in 2014, the year before Gray's death and the charges against the officers, to about 18,000 [as of November 2017]. This happened as homicides soared from 211 in 2014 to 344 in 2015 – an increase of 63%."[280] Simon's HBO miniseries We Own This City aired in April 2022 and covered many of the events surrounding the death of Freddie Gray and the work slowdown by the Baltimore Police Department during that time period.

In the six years between 2016 and 2022, Baltimore tallied 318, 342, 309, 348, 335, 338, and 335 homicides, respectively.[281] In 2023, Baltimore saw a 20% drop in homicides to 263.[282]

Baltimore is protected by the over 1,800 professional firefighters of the Baltimore City Fire Department (BCFD). It was founded in December 1858 and began operating the following year. Replacing several warring independent volunteer companies since the 1770s and the confusion resulting from a riot involving the "Know-Nothing" political party two years before, the establishment of a unified professional fire fighting force was a major advance in urban governance. The BCFD operates out of 37 fire stations located throughout the city and has a long history and sets of traditions in its various houses and divisions.

Since the legislative redistricting in 2002, Baltimore has had six legislative districts located entirely within its boundaries, giving the city six seats in the 47-member Maryland Senate and 18 in the 141-member Maryland House of Delegates.[283][284] During the previous 10-year period, Baltimore had four legislative districts within the city limits, but four others overlapped the Baltimore County line.[285] As of January 2011[update], all of Baltimore's state senators and delegates were Democrats.[283]

Two of the state's eight congressional districts include portions of Baltimore: the 2nd, represented by Dutch Ruppersberger and the 7th, represented by Kweisi Mfume. Both are Democrats. A Republican has not represented a significant portion of Baltimore in Congress since John Boynton Philip Clayton Hill represented the 3rd District in 1927, and has not represented any of Baltimore since the Eastern Shore-based 1st District lost its share of Baltimore after the 2000 census. It was represented by Republican Wayne Gilchrest at the time.

Maryland's senior United States senator, Ben Cardin, is from Baltimore. He is one of three people in the last four decades to have represented the 3rd District before being elected to the United States Senate. Paul Sarbanes represented the 3rd from 1971 until 1977, when he was elected to the first of five terms in the Senate. Sarbanes was succeeded by Barbara Mikulski, who represented the 3rd from 1977 to 1987. Mikulski was succeeded by Cardin, who held the seat until handing it to John Sarbanes upon his election to the Senate in 2007.[286]

The Postal Service's Baltimore Main Post Office is located at 900 East Fayette Street in the Jonestown area.[288]

The national headquarters for the United States Social Security Administration is located in Woodlawn, just outside of Baltimore.