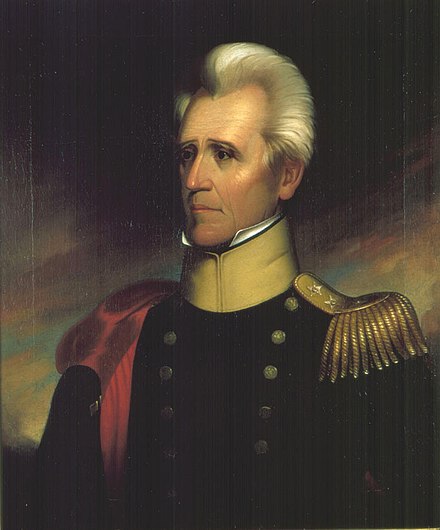

Семинольские войны (также известные как Флоридские войны ) были серией из трех военных конфликтов между Соединенными Штатами и семинолами , которые произошли во Флориде примерно между 1816 и 1858 годами. Семинолы — индейская нация , которая объединилась на севере Флориды в начале 1700-х годов, когда эта территория все еще была испанским колониальным владением . Напряженность между семинолами и поселенцами в недавно обретших независимость Соединенных Штатах росла в начале 1800-х годов, в основном потому, что рабы регулярно бежали из Джорджии в испанскую Флориду, побуждая рабовладельцев проводить рабовладельческие набеги через границу. Серия трансграничных стычек переросла в Первую семинольскую войну в 1817 году, когда американский генерал Эндрю Джексон возглавил вторжение на территорию, несмотря на возражения испанцев. Войска Джексона разрушили несколько городов семинолов и черных семинолов , а также ненадолго заняли Пенсаколу, прежде чем уйти в 1818 году. Вскоре США и Испания договорились о передаче территории по Договору Адамса-Ониса 1819 года.

Соединенные Штаты овладели Флоридой в 1821 году и вынудили семинолов покинуть свои земли во Флоридском выступе и перебраться в большую индейскую резервацию в центре полуострова в соответствии с Договором Молтри-Крик . Однако примерно через десять лет федеральное правительство под руководством президента Соединенных Штатов Эндрю Джексона потребовало, чтобы они полностью покинули Флориду и перебрались на Индейскую территорию (современная Оклахома ) в соответствии с Законом о переселении индейцев 1830 года . Несколько групп неохотно подчинились, но большинство оказало яростное сопротивление, что привело ко Второй войне семинолов (1835-1842), которая была самым продолжительным и масштабным из трех конфликтов. Первоначально менее 2000 воинов-семинолов использовали тактику партизанской войны «бей и беги» и знание местности, чтобы уклониться и расстроить объединенные силы армии и морской пехоты США, которые выросли до более чем 30 000 человек. Вместо того чтобы продолжать преследование этих небольших отрядов, американские командиры в конечном итоге изменили свою стратегию и сосредоточились на поиске и уничтожении скрытых деревень и посевов семинолов, оказывая все большее давление на участников сопротивления, заставляя их сдаваться или умирать от голода вместе со своими семьями.

Большая часть популяции семинолов была переселена на Индейскую территорию или убита к середине 1840-х годов, хотя несколько сотен поселились на юго-западе Флориды , где им разрешили остаться в условиях непростого перемирия. Напряженность из-за роста близлежащего Форт-Майерса привела к возобновлению военных действий, и в 1855 году разразилась Третья война семинолов . К моменту прекращения активных боевых действий в 1858 году несколько оставшихся во Флориде групп семинолов бежали вглубь Эверглейдс, чтобы высадиться там, не желая американских поселенцев .

В целом, войны с семинолами были самой продолжительной, самой дорогостоящей и самой смертоносной из всех войн с американскими индейцами .

Испанская Флорида была основана в 1500-х годах, когда Испания предъявила права на земли, исследованные несколькими экспедициями по будущим юго-востокам Соединенных Штатов . Заражение коренных народов Флориды болезнями привело к резкому сокращению первоначального коренного населения в течение следующего столетия, и большинство оставшихся народов апалачи и текеста поселились в ряде миссий, разбросанных по всей северной Флориде. Однако Испания так и не установила реального контроля над своими обширными претензиями за пределами непосредственной близости от своих разбросанных миссий и городов Сент-Огастин и Пенсакола , и британские поселенцы основали несколько колоний вдоль Атлантического побережья в течение 1600-х годов. После создания провинции Каролина в конце 17 века серия набегов британских поселенцев из Каролин и их индейских союзников на испанскую Флориду опустошила как систему миссий, так и оставшееся коренное население.

Британские поселенцы неоднократно вступали в конфликт с коренными американцами по мере того, как колонии расширялись дальше на запад, что приводило к потоку беженцев, переселявшихся в безлюдные районы Флориды. Большинство этих беженцев были индейцами Маскоги (Крик) из Джорджии и Алабамы, и в 1700-х годах они объединились с другими коренными народами, чтобы основать независимые вождества и деревни по всему выступу Флориды , поскольку они объединились в новую культуру, которая стала известна как семинолы. [5]

Начиная с 1730-х годов Испания установила политику предоставления убежища беглым рабам в попытке ослабить британские южные колонии . Сотни чернокожих людей бежали от рабства во Флориду в течение последующих десятилетий, большинство из них поселились недалеко от Сент-Огастина в Форт-Мозе , а несколько жили среди семинолов, которые относились к ним с разной степенью равенства. [6] Их число увеличилось во время и после Американской войны за независимость , и стало обычным явлением находить поселения черных семинолов либо вблизи городов семинолов, либо живущих независимо, например, в Негро-форте на реке Апалачикола . [7] Наличие поблизости убежища для свободных африканцев считалось угрозой институту рабства движимого имущества на юге Соединенных Штатов, и поселенцы в приграничных штатах Миссисипи и Джорджия , в частности, обвиняли семинолов в подстрекательстве рабов к побегу, а затем в краже их человеческой собственности. [8] В ответ владельцы плантаций организовали многократные рейды в испанскую Флориду, в ходе которых они захватывали африканцев, обвиняя их в том, что они сбежали из рабства, и преследовали деревни семинолов вблизи границы, в результате чего банды семинолов проникали на территорию США и устраивали ответные атаки. [9]

Растущая пограничная напряженность достигла апогея 26 декабря 1817 года, когда Военное министерство США издало приказ, предписывающий генералу Эндрю Джексону лично взять командование на себя и взять под контроль семинолов, что ускорило Первую семинольскую войну. [10] Войне предшествовало разрушение негритянского форта в июле 1816 года, а впоследствии войска Джексона уничтожили несколько поселений семинолов/криков и микосуки, включая Фоултаун, преследуя их, а также черных семинолов и союзных им маронов по всей северной Флориде в 1818 году. Экспедиция Джексона достигла кульминации в апреле 1818 года с инцидентом в Арбутноте и Амбристере . Испанское правительство выразило возмущение «карательными экспедициями» Джексона [11] на их территорию и его кратковременной оккупацией Пенсаколы, столицы их колонии в Западной Флориде. Но, как стало ясно из нескольких местных восстаний и других форм «пограничной анархии», [11] Испания больше не могла ни защищать, ни контролировать Флориду и в конечном итоге согласилась уступить ее Соединенным Штатам по Договору Адамса-Ониса 1819 года, причем передача состоялась в 1821 году. [12] Согласно условиям Договора Молтри-Крик (1823) между Соединенными Штатами и нацией семинолов, семинолы были переселены из Северной Флориды в резервацию в центре полуострова Флорида, а Соединенные Штаты построили ряд фортов и торговых постов вдоль побережья залива и Атлантического океана, чтобы обеспечить соблюдение договора. [2]

Вторая война семинолов (1835–1842) началась в результате того, что Соединенные Штаты в одностороннем порядке аннулировали Договор Молтри-Крик и потребовали, чтобы все семинолы переселились на Индейскую территорию в современной Оклахоме в соответствии с Законом о переселении индейцев (1830). После нескольких ультиматумов и ухода нескольких кланов семинолов в соответствии с Договором Пэйнс-Лэндинг (1832), военные действия начались в декабре 1835 года с битвы при Дейде и продолжались в течение следующих нескольких лет серией сражений по всему полуострову и распространились на Флорида-Кис . Хотя бойцы семинолов находились в тактическом и численном невыгодном положении, военные лидеры семинолов эффективно использовали партизанскую войну , чтобы расстроить военные силы Соединенных Штатов, которые в конечном итоге насчитывали более 30 000 регулярных солдат, ополченцев и добровольцев. [13] Генерал Томас Сидней Джесап был отправлен во Флориду, чтобы принять командование кампанией в 1836 году. Вместо того, чтобы тщетно преследовать отряды семинольских бойцов по территории, как это делали предыдущие командиры, Джесап изменил тактику и занялся поиском, захватом или уничтожением домов, скота, ферм и связанных с ними припасов семинолов, тем самым заставляя их голодать; стратегия, которую будет дублировать генерал У. Т. Шерман в своем марше к морю во время Гражданской войны в США . Джесап также санкционировал спорное похищение лидеров семинолов Оцеолы и Миканопи, заманив их под ложный флаг перемирия. [14] Генерал Джесуп явно нарушил правила войны и провел 21 год, защищая себя по этому поводу: «С расстояния более чем столетия, вряд ли стоит пытаться украсить захват каким-либо иным ярлыком, кроме как предательством » . [15] К началу 1840-х годов многие семинолы были убиты, и еще больше были вынуждены из-за надвигающегося голода сдаться и переселиться на Индейскую территорию. Хотя официального мирного договора не было, несколько сотен семинолов остались на юго-западе Флориды после того, как активный конфликт свернули. [2]

Третья война семинолов (1855–1858) началась, когда рост числа поселенцев на юго-западе Флориды привел к росту напряженности с семинолами, проживающими в этом районе. В декабре 1855 года военнослужащие армии США обнаружили и уничтожили большую плантацию семинолов к западу от Эверглейдс , возможно, чтобы намеренно спровоцировать насильственный ответ, который привел бы к изгнанию оставшихся граждан семинолов из региона. Холата Микко , лидер семинолов, известный белым как Билли Боулегс, ответил набегом около Форт-Майерса , что привело к серии ответных набегов и небольших стычек без крупных сражений. И снова военная стратегия Соединенных Штатов заключалась в том, чтобы нацелиться на мирных жителей семинолов, уничтожив их запасы продовольствия. К 1858 году большинство оставшихся семинолов, уставших от войны и столкнувшихся с голодом, согласились на переселение на Индейскую территорию в обмен на обещания безопасного прохода и денежных выплат. По оценкам, от 200 до 500 семинолов в небольших семейных группах все еще отказывались уходить и отступили вглубь Эверглейдс и Большого Кипарисового болота, чтобы жить на землях, которые американские поселенцы считали непригодными. [2]

Первоначальные коренные народы Флориды значительно сократились в численности после прибытия европейских исследователей в начале 1500-х годов, в основном потому, что коренные американцы имели слабую сопротивляемость к болезням, недавно завезенным из Европы. Подавление испанцами восстаний коренных народов еще больше сократило население северной Флориды до начала 1600-х годов, когда создание ряда испанских миссий улучшило отношения и стабилизировало население. [16] [17]

Начиная с конца XVII века, набеги британских поселенцев из колонии Каролина и их союзников-индейцев начали еще один резкий спад коренного населения. К 1707 году поселенцы, обосновавшиеся в Каролине, и их союзники - индейцы ямаси убили, увезли или изгнали большую часть оставшихся коренных жителей во время серии набегов по всей Флоридской выступе и по всей длине полуострова. В первом десятилетии XVIII века, по словам губернатора Ла-Флориды, в качестве рабов было взято 10 000–12 000 индейцев, а к 1710 году наблюдатели отметили, что северная Флорида практически обезлюдела. Все испанские миссии закрылись, так как без коренных жителей им нечего было делать. Немногие оставшиеся коренные жители бежали на запад в Пенсаколу и дальше или на восток в окрестности Сент-Огастина . Когда Испания уступила Флориду Великобритании в рамках Парижского договора в 1763 году, большинство индейцев Флориды отправились с испанцами на Кубу или в Новую Испанию . [16] [18] [19]

В середине 1700-х годов небольшие группы из различных индейских племен с юго-востока Соединенных Штатов начали переселяться на незанятые земли Флориды. В 1715 году ямаси переехали во Флориду в качестве союзников испанцев после конфликтов с колонистами из провинции Каролина . Люди племени крик , сначала в основном из Нижнего крика , но позже включая Верхний крик , также начали переселяться во Флориду из района Джорджии. Микасуки , говорящие на языке хитчити , поселились вокруг того, что сейчас называется озером Миккосуки около Таллахасси . (Потомки этой группы сохранили отдельную племенную идентичность как сегодняшние Миккосуки .)

Другая группа носителей языка хитчити, во главе с Каукипером , поселилась в том, что сейчас является округом Алачуа , районе, где испанцы содержали скотоводческие ранчо в 17 веке. Поскольку одно из самых известных ранчо называлось Ла Чуа , регион стал известен как « Прерия Алачуа ». Испанцы в Сент-Огастине начали называть ручей Алачуа Cimarrones , что примерно означало «дикие» или «беглецы». Это было вероятным происхождением термина «семинолы». [20] [21] Это название в конечном итоге было применено к другим группам во Флориде, хотя индейцы по-прежнему считали себя членами разных племен. Другие группы коренных американцев во Флориде во время Семинольских войн включали чокто , ючи , испанских индейцев (так их называли, потому что считалось, что они произошли от калуса ) и «индейцев ранчо», которые жили в испанско-кубинских рыболовных лагерях (ранчо) на побережье Флориды. [22]

В 1738 году испанский губернатор Флориды Мануэль де Монтиано построил и основал Форт Мозе как свободное поселение чернокожих. Беглые африканские и афроамериканские рабы, которые могли добраться до форта, были по сути свободными. Многие были из Пенсаколы; некоторые были свободными гражданами, хотя другие бежали с территории Соединенных Штатов. Испанцы предложили рабам свободу и землю во Флориде. Они набрали бывших рабов в ополчение, чтобы помочь защитить Пенсаколу и Форт Мозе. Другие беглые рабы присоединились к семинольским отрядам как свободные члены племени.

Большинство бывших рабов в Форт-Мозе отправились на Кубу с испанцами, когда они покинули Флориду в 1763 году, в то время как другие жили с различными группами индейцев или рядом с ними. Беглые рабы из Каролины и Джорджии продолжали свой путь во Флориду, поскольку Подземная железная дорога шла на юг. Чернокожие, которые остались с семинолами или позже присоединились к ним, интегрировались в племена, изучая языки, принимая их одежду и вступая в смешанные браки. Чернокожие умели заниматься сельским хозяйством и служили переводчиками между семинолами и белыми. Некоторые из черных семинолов , как их называли, стали важными вождями племен. [23]

Во время Войны за независимость США британцы, контролировавшие Флориду, нанимали семинолов для набегов на поселения патриотов на границе с Джорджией. Военная неразбериха позволила американским рабам бежать во Флориду, где местные британские власти обещали им свободу в обмен на военную службу. Эти события сделали новых врагов Соединенных Штатов семинолов. В 1783 году в рамках договора, положившего конец Войне за независимость , Флорида была возвращена Испании. Власть Испании над Флоридой была слабой, поскольку она содержала только небольшие гарнизоны в Сент-Огастине, Сент-Марксе и Пенсаколе . Они не контролировали границу между Флоридой и Соединенными Штатами и не могли действовать против штата Маскоги, созданного в 1799 году, задуманного как единая нация американских индейцев, независимая как от Испании, так и от Соединенных Штатов, до 1803 года, когда обе нации сговорились поймать его основателя. Микасуки и другие группы семинолов все еще занимали города на американской стороне границы, в то время как американские сквоттеры переселялись в испанскую Флориду. [24]

Британцы разделили Флориду на Восточную Флориду и Западную Флориду в 1763 году, разделение, которое испанцы сохранили, когда они вернули себе Флориду в 1783 году. Западная Флорида простиралась от реки Апалачикола до реки Миссисипи . Вместе с владением Луизианой испанцы контролировали нижние течения всех рек, впадающих в Соединенные Штаты к западу от Аппалачских гор . Это запрещало США транспортировать и торговать на нижнем течении Миссисипи. В дополнение к своему желанию расширяться к западу от гор, Соединенные Штаты хотели приобрести Флориду. Они хотели получить свободную торговлю на западных реках и не допустить использования Флориды в качестве базы для возможного вторжения в США европейской страны. [25]

Чтобы получить порт в Мексиканском заливе с безопасным доступом для американцев, дипломатам Соединенных Штатов в Европе было поручено попытаться купить остров Орлеан и Западную Флориду у любой страны, которой они принадлежали. Когда Роберт Ливингстон обратился к Франции в 1803 году с предложением купить остров Орлеан, французское правительство предложило продать его и всю Луизиану. Хотя покупка Луизианы превышала их полномочия, Ливингстон и Джеймс Монро (который был отправлен, чтобы помочь ему договориться о продаже) в обсуждениях с Францией преследовали цель, чтобы территория к востоку от Миссисипи до реки Пердидо была частью Луизианы. В рамках договора о покупке Луизианы 1803 года Франция дословно повторила статью 3 своего договора 1800 года с Испанией, таким образом явно подчинив Соединенные Штаты правам Франции и Испании. [26] стр. 288–291

Двусмысленность в этой третьей статье соответствовала целям посланника США Джеймса Монро, хотя ему пришлось принять толкование, которое Франция не утверждала, а Испания не допускала. [27] стр. 83 Монро рассмотрел каждый пункт третьей статьи и истолковал первый пункт так, как будто Испания с 1783 года считала Западную Флориду частью Луизианы. Второй пункт лишь прояснил первый пункт. Третий пункт ссылался на договоры 1783 и 1795 годов и был разработан для защиты прав Соединенных Штатов. Затем этот пункт просто ввел в действие остальные. [27] стр. 84–85 По словам Монро, Франция никогда не расчленяла Луизиану, пока она находилась во владении. (Он считал 3 ноября 1762 года датой окончания французского владения, а не 1769 год, когда Франция официально передала Луизиану Испании).

Президент Томас Джефферсон изначально считал, что покупка Луизианы включала Западную Флориду и давала Соединенным Штатам серьезные права на Техас. [28] Президент Джефферсон обратился к официальным лицам США в приграничной зоне за советом о границах Луизианы, наиболее информированные из которых не верили, что она включает Западную Флориду. [27] стр. 87–88 Позже, в письме 1809 года, Джефферсон фактически признал, что Западная Флорида не была владением Соединенных Штатов. [29] стр. 46–47

Во время переговоров с Францией посланник США Роберт Ливингстон написал Мэдисону девять отчетов, в которых он утверждал, что Западная Флорида не находится во владении Франции. [29] стр. 43–44 В ноябре 1804 года в ответ Ливингстону Франция объявила американские претензии на Западную Флориду абсолютно необоснованными. [27] стр. 113–116 После провала миссии Монро в 1804–1805 годах Мэдисон был готов полностью отказаться от американских претензий на Западную Флориду. [27] стр. 118 В 1805 году последнее предложение Монро Испании о получении Западной Флориды было полностью отклонено, и американские планы по созданию таможни в Мобайл-Бей в 1804 году были отменены из-за протестов испанцев. [26] стр. 293

Соединенные Штаты также надеялись заполучить все побережье Мексиканского залива к востоку от Луизианы, и были разработаны планы предложить купить оставшуюся часть Западной Флориды (между реками Пердидо и Апалачикола) и всю Восточную Флориду. Однако вскоре было решено, что вместо того, чтобы платить за колонии, Соединенные Штаты предложат взять на себя испанские долги американским гражданам [Примечание 1] в обмен на уступку Испанией Флорид. Американская позиция заключалась в том, что они налагали залог на Восточную Флориду вместо захвата колонии для погашения долгов. [31]

В 1808 году Наполеон вторгся в Испанию, заставил Фердинанда VII , короля Испании, отречься от престола и поставил на престол своего брата Жозефа Бонапарта . Сопротивление французскому вторжению объединилось в национальное правительство, Кортесы Кадиса . Затем это правительство вступило в союз с Британией против Франции. Этот союз вызвал опасения в Соединенных Штатах, что Британия создаст военные базы в испанских колониях, включая Флориды, и таким образом потенциально поставит под угрозу безопасность южных границ США [32]

К 1810 году, во время Пиренейской войны , Испания была в значительной степени захвачена французской армией. Восстания против испанских властей вспыхнули во многих ее американских колониях. Поселенцы в Западной Флориде и на прилегающей территории Миссисипи начали организовываться летом 1810 года, чтобы захватить Мобил и Пенсаколу , последний из которых находился за пределами части Западной Флориды, на которую претендовали Соединенные Штаты.

Жители западной части Западной Флориды (между реками Миссисипи и Перл ) организовали съезд в Батон-Руж летом 1810 года. Съезд был обеспокоен поддержанием общественного порядка и предотвращением перехода контроля над округом во французские руки; сначала он пытался создать правительство под местным контролем, которое было бы номинально лояльно Фердинанду VII. Узнав, что испанский губернатор округа обратился за военной помощью для подавления «восстания», жители округа Батон-Руж 23 сентября свергли местные испанские власти, захватив испанский форт в Батон-Руж. 26 сентября съезд объявил Западную Флориду независимой. [33]

В недавно провозглашенной республике быстро сформировались происпанские, проамериканские и пронезависимые фракции. Проамериканская фракция обратилась к Соединенным Штатам с просьбой аннексировать территорию и оказать финансовую помощь. 27 октября 1810 года президент США Джеймс Мэдисон провозгласил, что Соединенные Штаты должны завладеть Западной Флоридой между реками Миссисипи и Пердидо, основываясь на слабом утверждении, что она является частью Луизианской покупки. [34]

Мэдисон уполномочил Уильяма К. К. Клейборна , губернатора Территории Орлеан , завладеть территорией. Он вошел в столицу Сент-Фрэнсисвилл со своими войсками 6 декабря 1810 года и в Батон-Руж 10 декабря 1810 года. Правительство Западной Флориды выступило против аннексии, предпочитая вести переговоры об условиях присоединения к Союзу. Губернатор Фулвар Скипвит провозгласил, что он и его люди «окружат Флагшток и умрут, защищая его». [35] : 308 Однако Клейборн отказался признать легитимность правительства Западной Флориды, и Скипвит и законодательный орган в конечном итоге согласились принять прокламацию Мэдисона. Клейборн занял только территорию к западу от реки Перл (нынешняя восточная граница Луизианы). [36] [37] [Примечание 2]

Хуан Висенте Фольч-и-Хуан , губернатор Западной Флориды, надеясь избежать боевых действий, отменил таможенные пошлины на американские товары в Мобиле и предложил сдать всю Западную Флориду Соединенным Штатам, если он не получит помощи или инструкций из Гаваны или Веракруса к концу года. [38]

Опасаясь, что Франция захватит всю Испанию, и предполагаемым результатом этого будет то, что испанские колонии либо попадут под контроль Франции, либо будут захвачены британцами, в январе 1811 года Мэдисон обратился в Конгресс США с просьбой принять закон, разрешающий Соединенным Штатам взять на себя «временное владение» любой территорией, прилегающей к Соединенным Штатам к востоку от реки Пердидо, т. е. остаток Западной Флориды и всю Восточную Флориду. Соединенным Штатам будет разрешено либо принять передачу территории от «местных властей», либо оккупировать территорию, чтобы не допустить ее попадания в руки иностранной державы, кроме Испании. Конгресс обсудил и принял 15 января 1811 года запрошенную резолюцию на закрытом заседании, и при условии, что резолюция может храниться в секрете вплоть до марта 1812 года. [39]

В 1811 году американские войска заняли большую часть испанской территории между реками Перл и Пердидо (современное побережье Миссисипи и Алабамы ), за исключением области вокруг Мобила. [40] В 1813 году Мобил был занят войсками Соединенных Штатов . [41]

Мэдисон отправил Джорджа Мэтьюза разобраться со спорами по поводу Западной Флориды. Когда Висенте Фолч отменил свое предложение передать оставшуюся часть Западной Флориды США, Мэтьюз отправился в Восточную Флориду, чтобы вступить в борьбу с испанскими властями. Когда эта попытка провалилась, Мэтьюз, в экстремальной интерпретации своих приказов, задумал спровоцировать восстание, подобное восстанию в округе Батон-Руж. [42]

В 1812 году генерал Джордж Мэтьюз был уполномочен президентом Джеймсом Мэдисоном обратиться к испанскому губернатору Восточной Флориды в попытке завладеть территорией. Его инструкциями было завладеть любой частью территории Флориды после заключения «договоренности» с «местными властями» о передаче владения США. За исключением этого или вторжения другой иностранной державы, они не должны были завладеть никакой частью Флориды. [43] [44] [45] Большинство жителей Восточной Флориды были довольны статус-кво, поэтому Мэтьюз собрал отряд добровольцев в Джорджии, пообещав им оружие и продолжающуюся оборону. 16 марта 1812 года этот отряд «Патриотов» с помощью девяти канонерских лодок ВМС США захватил город Фернандина на острове Амелия , к югу от границы с Джорджией, примерно в 50 милях к северу от Сент-Огастина. [46]

17 марта патриоты и испанские власти города подписали статьи о капитуляции. [43] На следующий день отряд из 250 регулярных солдат США был доставлен из Пойнт-Питер, штат Джорджия, и патриоты сдали город генералу Джорджу Мэтьюзу, который немедленно поднял флаг США. [44] Как и было согласовано, патриоты удерживали Фернандину всего один день, прежде чем передать власть американским военным, что вскоре дало контроль США над побережьем Сент-Огастину. В течение нескольких дней патриоты вместе с полком регулярных войск и грузинскими добровольцами двинулись к Сент-Огастину. На этом марше патриоты немного опередили американские войска. Патриоты объявили бы о владении некоторой территорией, подняли бы флаг патриотов и как «местные власти» сдали бы территорию войскам США, которые затем заменили бы флаг патриотов американским флагом. Патриоты не столкнулись бы с сопротивлением во время своего марша, обычно с генералом Мэтьюзом. [44] По свидетельствам очевидцев, патриоты не смогли бы продвинуться вперед, если бы не защита американских войск, и не смогли бы удержать свои позиции в стране без помощи американских войск. Американские войска и патриоты действовали в тесном сотрудничестве, маршируя, разбивая лагерь, собирая продовольствие и сражаясь вместе. Таким образом, американские войска поддерживали патриотов, [44] которые, однако, не смогли взять Кастильо-де-Сан-Маркос в Сент-Огастине .

Как только правительство США было уведомлено об этих событиях, Конгресс встревожился возможностью быть втянутым в войну с Испанией, и усилия провалились. Государственный секретарь Джеймс Монро немедленно дезавуировал действия и освободил генерала Мэтьюза от его полномочий 9 мая на том основании, что ни одно из предписанных обстоятельств не произошло. [43] Однако мирные переговоры с испанскими властями были длительными и медленными. Летом и осенью войска США и патриотов добывали продовольствие и грабили почти все плантации и фермы, большинство из которых были брошены их владельцами. Войска хватали все, что могли найти. Запасы продовольствия были израсходованы, урожай уничтожен или скормлен лошадям, все виды движимого имущества разграблены или уничтожены, здания и заборы сожжены, скот и свиньи убиты или украдены для разделки, а рабы часто разогнаны или похищены. Это продолжалось до мая 1813 года и оставило ранее заселенные части в состоянии запустения. [44]

В июне 1812 года Джордж Мэтьюз встретился с королем Пейном и другими лидерами семинолов . После встречи Мэтьюз считал, что семинолы сохранят нейтралитет в конфликте. Себастьян Кинделан-и-О'Реган , губернатор Восточной Флориды, пытался склонить семинолов сражаться на стороне испанцев. Некоторые из семинолов хотели сражаться с грузинами в составе Армии патриотов, но король Пейн и другие выступали за мир. Семинолы были недовольны испанским правлением, сравнивая обращение с ними под испанцами неблагоприятно с тем, которое получали от британцев, когда они удерживали Флориду. Ахая , или Хранитель коров, предшественник короля Пейна, поклялся убить 100 испанцев, и на смертном одре сокрушался, что убил только 84. На второй встрече с лидерами Армии патриотов семинолы снова пообещали сохранять нейтралитет. [47]

Чернокожие, проживающие во Флориде за пределами Сент-Огастина, многие из которых были бывшими рабами из Джорджии и Южной Каролины, не были расположены к нейтралитету. Часто рабы семинолов только по названию, они жили на свободе и боялись потерять эту свободу, если Соединенные Штаты отнимут Флориду у Испании. Многие чернокожие записались на защиту Сент-Огастина, в то время как другие призывали семинолов сражаться с армией патриотов. На третьей встрече с лидерами семинолов лидеры армии патриотов пригрозили семинолам уничтожением, если они будут сражаться на стороне испанцев. Эта угроза дала преимущество семинолам, выступающим за войну, во главе с братом короля Пейна Болеком (также известным как Боулегс). Присоединившись к воинам из Аллигатора (недалеко от современного Лейк-Сити ) и других городов, семинолы отправили 200 индейцев и 40 чернокожих, чтобы атаковать патриотов. [48]

В ответ на набеги семинолов в сентябре 1812 года полковник Дэниел Ньюнан повел 117 ополченцев Джорджии в попытке захватить земли семинолов Алачуа вокруг прерии Пэйна . Силы Ньюнана так и не достигли городов семинолов, потеряв восемь человек убитыми, восемь пропавшими без вести и девять ранеными после сражений с семинолами в течение более недели. Четыре месяца спустя подполковник Томас Адамс Смит повел 220 солдат регулярной армии США и добровольцев из Теннесси в рейде на город Пэйн, главный город семинолов Алачуа. Силы Смита обнаружили несколько индейцев, но семинолы Алачуа покинули город Пэйн и двинулись на юг. Сжег город Пэйн, силы Смита вернулись на территорию, удерживаемую американцами. [49]

Переговоры завершились выводом войск США в 1813 году. 6 мая 1813 года армия спустила флаг в Фернандине и пересекла реку Сент-Мэрис в Джорджию с оставшимися войсками. [50] [51]

После того, как правительство Соединенных Штатов отказалось от поддержки Территории Восточной Флориды и вывело американские войска и корабли с испанской территории, большинство Патриотов в Восточной Флориде либо отступили в Джорджию, либо приняли предложение об амнистии от испанского правительства. [52] Некоторые из Патриотов все еще мечтали претендовать на земли во Флориде. Один из них, Бакнер Харрис , участвовал в вербовке людей в Армию Патриотов [53] и был президентом Законодательного совета Территории Восточной Флориды. [54] Харрис стал лидером небольшой группы Патриотов, которые бродили по сельской местности, угрожая жителям, которые приняли помилование от испанского правительства. [55]

Бакнер Харрис разработал план создания поселения в стране Алачуа [Примечание 3] при финансовой поддержке штата Джорджия, уступке земли по договору от семинолов и предоставлении земли Испанией. Харрис обратился к губернатору Джорджии с просьбой о деньгах, заявив, что поселение американцев в стране Алачуа поможет держать семинолов подальше от границы Джорджии и сможет перехватывать беглых рабов из Джорджии до того, как они доберутся до семинолов. К сожалению для Харриса, у Джорджии не было доступных средств. Харрис также надеялся приобрести землю вокруг прерии Алачуа ( прерии Пейнса ) по договору от семинолов, но не смог убедить семинолов встретиться с ним. Испанцы также не были заинтересованы в общении с Харрисом. [57]

В январе 1814 года 70 человек во главе с Бакнером Харрисом пересекли границу Джорджии и направились в страну Алачуа. К ним присоединилось еще больше людей, пока они путешествовали по Восточной Флориде, и когда они достигли места сожжения города Пэйн в 1812 году, в группе было более 90 человек. Мужчины построили двухэтажный блокгауз площадью 25 футов, который назвали Форт Митчелл , в честь Дэвида Митчелла , бывшего губернатора Джорджии и сторонника вторжения патриотов в Восточную Флориду. [Примечание 4] К тому времени, когда блокгауз был достроен, в Элотчауэе, как сообщалось, находилось более 160 человек. 25 января 1814 года поселенцы создали правительство под названием «Округ Элотчауэй Республики Восточная Флорида», с Бакнером Харрисом в качестве директора. Затем Законодательный совет подал петицию в Конгресс Соединенных Штатов о признании округа Элотчауэй территорией Соединенных Штатов. [60] [61] Петицию подписали 106 «граждан Элотчауэя». Поселенцы Элотчауэя разбили фермерские участки и начали сажать урожай. [62] [63] Некоторые из мужчин, по-видимому, привезли с собой семьи, так как 15 марта 1814 года в Элотчауэе родился ребенок. [64]

Бакнер Харрис надеялся расширить американское поселение в стране Алачуа и отправился в одиночку исследовать эту область. 5 мая 1814 года он попал в засаду и был убит семинолами. Без Харриса округ Элотчауэй рухнул. Форт Митчелл был заброшен, и все поселенцы уехали в течение двух недель. [65] Некоторые из мужчин в Форте Митчелл, подписавшие петицию в Конгресс, снова поселились в стране Алачуа после того, как Флорида была передана Соединенным Штатам в 1821 году. [66]

Нет единого мнения о датах начала и окончания Первой семинольской войны. Армейская пехота США указывает, что она длилась с 1814 по 1819 год . [67] Военно-морской исторический центр США указывает даты 1816–1818 годов. [36] Другой армейский сайт датирует войну 1817–1818 годами. [68] Наконец, история подразделения 1-го батальона 5-го полевого артиллерийского полка описывает войну как произошедшую исключительно в 1818 году. [69]

Во время войны с криками (1813–1814) полковник Эндрю Джексон стал национальным героем после своей победы над Creek Red Sticks в битве при Хорсшу-Бенд . После своей победы Джексон навязал договор Форт-Джексон на реке Крик, что привело к потере значительной части территории криков в том, что сегодня является южной Джорджией и центральной и южной Алабамой. В результате многие крики покинули Алабаму и Джорджию и перебрались в Испанскую Западную Флориду. Беженцы криков присоединились к семинолам Флориды. [70]

В 1814 году Великобритания все еще находилась в состоянии войны с Соединенными Штатами , и многие британские командиры начали заручаться военной помощью местных индейцев. [ ласковые слова ] В мае 1814 года британские войска вошли в устье реки Апалачикола и раздали оружие воинам семинолов и криков вместе с беглыми американскими рабами. [ сомнительный – обсудить ] Британцы двинулись вверх по реке и начали строить форт в Проспект-Блафф . [71] Впоследствии должна была прибыть рота королевской морской пехоты под командованием подполковника Эдварда Николса , но в конце августа 1814 года ее пригласили перебраться в Пенсаколу. [72] Капитан Николас Локьер с корабля HMS Sophie подсчитал , что в августе 1814 года в Пенсаколе находилось 1000 индейцев, из которых 700 были воинами. [73] Через два месяца после того, как британцы и их индейские союзники были отбиты от атаки на Форт Бойер около Мобила , американские войска под командованием генерала Джексона выбили британцев и испанцев из Пенсаколы и отогнали их обратно к реке Апалачикола. Им удалось продолжить работу над фортом в Проспект-Блафф.

Когда война 1812 года закончилась, все британские войска покинули Мексиканский залив, за исключением Николса и его войск в испанской Западной Флориде. Он руководил снабжением форта в Проспект-Блафф пушками, мушкетами и боеприпасами. Он сказал индейцам, что Гентский договор гарантировал возвращение всех индейских земель, потерянных Соединенными Штатами во время войны 1812 года, включая земли криков в Джорджии и Алабаме. [74] Поскольку семинолы не были заинтересованы в удержании форта, они вернулись в свои деревни. Перед тем как Николс ушел весной 1815 года, он передал форт беглым рабам и семинолам, которых он изначально набрал для возможных вторжений на территорию США во время войны. Когда слухи о форте распространились на американском Юго-Востоке , белые американцы назвали его « Негритянским фортом ». Американцы беспокоились, что это вдохновит их рабов на побег во Флориду или восстание. [75]

Признавая, что это была испанская территория, в апреле 1816 года Джексон сообщил губернатору Западной Флориды Хосе Масоту , что если испанцы не уничтожат форт, то это сделает он. Губернатор ответил, что у него нет сил, чтобы взять форт. [ необходима цитата ]

Джексон поручил бригадному генералу Эдмунду Пендлтону Гейнсу взять под контроль форт. Гейнс приказал полковнику Дункану Ламонту Клинчу построить Форт Скотт на реке Флинт к северу от границы с Флоридой. Гейнс сказал, что намерен снабжать Форт Скотт из Нового Орлеана по реке Апалачикола. Поскольку это означало бы прохождение через испанскую территорию и мимо негритянского форта, это позволило бы армии США следить за семинолами и негритянским фортом. Если бы форт обстрелял суда снабжения, у американцев был бы повод уничтожить его. [76]

В июле 1816 года флот снабжения Форта Скотт достиг реки Апалачикола. Клинч взял с собой отряд из более чем 100 американских солдат и около 150 воинов Нижнего Крика, включая вождя Тастаннуги Хатке (Белого Воина), чтобы защитить их проход. Флот снабжения встретил Клинча у Негритянского Форта , и его две канонерские лодки заняли позиции через реку от форта. Жители форта стреляли из своих пушек по вторгшимся американским солдатам и Крику, но не имели никакой подготовки в наведении оружия. Американские военные открыли ответный огонь, и девятый выстрел канонерских лодок, « горячий выстрел » (пушечное ядро, нагретое до красного свечения), приземлился в пороховом погребе форта . Взрыв сравнял форт с землей и был слышен на расстоянии более 100 миль (160 км) в Пенсаколе. [ необходима цитата ] Его называли «самым смертоносным выстрелом из пушки в американской истории». [77] Из 320 человек, которые, как известно, находились в форте, включая женщин и детей, более 250 погибли мгновенно, и многие другие вскоре умерли от полученных ранений. После того, как армия США разрушила форт, она покинула испанскую Флориду.

Американские сквоттеры и преступники совершили набег на семинолов, убивая жителей деревни и угоняя их скот. Негодование семинолов росло, и они отомстили, угнав скот обратно. [ необходима цитата ] 24 февраля 1817 года группа налетчиков убила миссис Гарретт, женщину, проживавшую в округе Кэмден, штат Джорджия , и ее двух маленьких детей. [78] [79]

Fowltown был деревней Mikasuki (Creek) на юго-западе Джорджии, примерно в 15 милях (24 км) к востоку от Форт-Скотта . Вождь Ниматла из Fowltown вступил в спор с командиром Форт-Скотта по поводу использования земли на восточной стороне реки Флинт, по сути заявив о суверенитете Mikasuki над этой территорией. Земля в южной Джорджии была уступлена Creeks по Договору Форт-Джексона, но Mikasukis не считали себя Creeks, не чувствовали себя связанными договором, который они не подписывали, и не признавали, что Creeks имели какое-либо право уступать земли Mikasuki. 21 ноября 1817 года генерал Гейнс послал отряд из 250 человек, чтобы захватить Fowltown. Первая попытка была отбита Mikasukis. На следующий день, 22 ноября 1817 года, Mikasukis были изгнаны из своей деревни. Некоторые историки датируют начало войны этим нападением на Фоултаун. Дэвид Брайди Митчелл , бывший губернатор Джорджии и агент племени криков в то время, заявил в докладе Конгрессу , что нападение на Фоултаун стало началом Первой семинольской войны. [80]

A week later a boat carrying supplies for Fort Scott, under the command of Lieutenant Richard W. Scott, was attacked on the Apalachicola River. There were forty to fifty people on the boat, including twenty sick soldiers, seven wives of soldiers, and possibly some children. (While there are reports of four children being killed by the Seminoles, they were not mentioned in early reports of the massacre, and their presence has not been confirmed.) Most of the boat's passengers were killed by the Indians. One woman was taken prisoner, and six survivors made it to the fort.[81]

While General Gaines had been under orders not to invade Florida, he later decided to allow short intrusions into Florida. When news of the Scott Massacre on the Apalachicola reached Washington, Gaines was ordered to invade Florida and pursue the Indians but not to attack any Spanish installations. However, Gaines had left for East Florida to deal with pirates who had occupied Fernandina. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun then ordered Andrew Jackson to lead the invasion of Florida.[82]

Jackson gathered his forces at Fort Scott in March 1818, including 800 U.S. Army regulars, 1,000 Tennessee volunteers, 1,000 Georgia militia,[83] and about 1,400 friendly Lower Creek warriors (under command of Brigadier General William McIntosh, a Creek chief). On March 15, Jackson's army entered Florida, marching down the banks of the Apalachicola River. When they reached the site of the Negro Fort, Jackson had his men construct a new fort, Fort Gadsden. The army then set out for the Mikasuki villages around Lake Miccosukee. The Indian town of Anhaica (today's Tallahassee) was burned on March 31, and the town of Miccosukee was taken the next day. More than 300 Indian homes were destroyed. Jackson then turned south, reaching Fort St. Marks (San Marcos) on April 6.[84]

Upon reaching St. Marks, Jackson wrote to the commandant of the fort, Don Francisco Caso y Luengo, to tell him that he had invaded Florida at the President's instruction.[85] He wrote that after capturing the wife of Chief Chennabee, she had testified to the Seminoles retrieving ammunition from the fort.[85] He explained that, because of this, the fort had already been taken over by the people living in the Mekasukian towns he had just destroyed and to prevent that from happening again, the fort would have to be guarded by American troops.[85] He justified this on the "principal of self defense."[85] By claiming that through this action he was a "Friend of Spain", Jackson was attempting to take possession of St. Marks by convincing the Spanish that they were allies with the American army against the Seminoles.[85] Luengo responded, agreeing that he and Jackson were allies but denying the story that Chief Chennabee's wife had told, claiming that the Seminoles had not taken ammunition from or possession of the fort.[85] He expressed to Jackson that he was worried about the challenges he would face if he allowed American troops to occupy the fort without first getting authorization from Spain.[85] Despite Leungo asking him not to occupy the fort, Jackson seized St. Marks on April 7.[85] There he found Alexander George Arbuthnot, a Scottish trader based out of the Bahamas. He traded with the Indians in Florida and had written letters to British and American officials on behalf of the Indians. He was rumored to be selling guns to the Indians and to be preparing them for war. He probably was selling guns, since the main trade item of the Indians was deer skins, and they needed guns to hunt the deer.[86] Two Indian leaders, Josiah Francis (Hillis Hadjo), a Red Stick Creek also known as the "Prophet" (not to be confused with Tenskwatawa), and Homathlemico, had been captured when they had gone out to an American ship flying the Union Flag that had anchored off of St. Marks. As soon as Jackson arrived at St. Marks, the two Indians were brought ashore and hanged without trial.[86]

Jackson left Fort St. Marks to attack the Native American Bolek's (aka "Bowlegs") old town and maroon villages (Nero's town) along the Suwannee River near the current Old Town, FL. On April 12, enroute to the Suwannee the U.S. army and allied Native Americans led by William McIntosh, found and attacked a Red Stick village led by Peter McQueen on the Econfina River. Close to 40 Red Sticks were killed, and about 100 women and children were captured.[citation needed] In the village, they found Elizabeth Stewart, the woman who had been captured in the attack (the Scott Massacre) on the supply boat on the Apalachicola River the previous November near modern Chattahochee, FL. Having destroyed the major Seminole and black villages, Jackson declared victory and sent the Georgia militiamen and the Lower Creeks home. The remaining army then returned to Fort St. Marks.[87]

About this time, Robert Ambrister, a former officer in the Corps of Colonial Marines, was captured by Jackson's troops. At St. Marks a military tribunal was convened, and Ambrister and Arbuthnot were charged with aiding the Seminoles and the Spanish, inciting them to war and leading them against the United States. Ambrister threw himself on the mercy of the court, while Arbuthnot maintained his innocence, saying that he had only been engaged in legal trade. The tribunal sentenced both men to death but then relented and changed Ambrister's sentence to fifty lashes and a year at hard labor. Jackson, however, reinstated Ambrister's death penalty. Ambrister was executed by a firing squad of American troops on April 29, 1818. Arbuthnot was hanged from the yardarm of his own ship.[88]

Jackson left a garrison at Fort St. Marks and returned to Fort Gadsden. Jackson had first reported that all was peaceful and that he would be returning to Nashville, Tennessee.

General Jackson later reported that Indians were gathering and being supplied by the Spanish, and he left Fort Gadsden with 1,000 men on May 7, headed for Pensacola. The governor of West Florida protested that most of the Indians at Pensacola were women and children and that the men were unarmed, but Jackson did not stop. Jackson also stated (in a letter to George W. Campbell) that the seizure of supplies meant for Fort Crawford gave additional reason for his march on Pensacola.[89] When he reached Pensacola on May 23, the governor and the 175-man Spanish garrison retreated to Fort Barrancas, leaving the city of Pensacola to Jackson. The two sides exchanged cannon fire for a couple of days, and then the Spanish surrendered Fort Barrancas on May 28. Jackson left Colonel William King as military governor of West Florida and went home.[90]

There were international repercussions to Jackson's actions. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams had just started negotiations with Spain for the purchase of Florida. Spain protested the invasion and seizure of West Florida and suspended the negotiations. Spain did not have the means to retaliate against the United States or regain West Florida by force, so Adams let the Spanish officials protest, then issued a letter (with 72 supporting documents) claiming that the United States was defending her national interests against the British, Spanish and Native Americans. In the letter he also apologized for the seizure of West Florida, said that it had not been American policy to seize Spanish territory, and offered to give St. Marks and Pensacola back to Spain. This notably did not include the return of Fort Gadsden.[91]

The British government protested the execution of two of its subjects who had never entered United States territory. A number of British commentators discussed the possibility of demanding reparations and taking reprisals. At the end, Britain refused to risk another war with the United States due to a variety of factors, including the increasing importance of British trade with the United States, particularly in grain and cotton.[92] British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh chose not to let the incident interfere with the warming relations between the two countries, and continued on with plans for the Anglo-American Convention of 1818.[91]

Spain, seeing that the British would not join them in making a strong denouncement of the Florida invasion, accepted and eventually resumed negotiations for the sale of Florida.[93] Defending Jackson's actions as necessary, and sensing that they strengthened his diplomatic standing, Adams demanded Spain either control the inhabitants of East Florida or cede it to the United States. An agreement was then reached whereby Spain ceded East Florida to the United States and renounced all claim to West Florida.[94]

There were also repercussions in America. Congressional committees held hearings into the irregularities of the Ambrister and Arbuthnot trials. While most Americans supported Jackson, some worried that Jackson could become a "man on horseback", a second Napoleon, and transform the United States into a military dictatorship. When Congress reconvened in December 1818, resolutions were introduced condemning Jackson's actions. Jackson was too popular, and the resolutions failed, but the Ambrister and Arbuthnot executions left a stain on his reputation for the rest of his life, although it was not enough to keep him from becoming president.[95]

Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1819 with the Adams–Onís Treaty, and the United States took possession in 1821. Effective government was slow in coming to Florida. General Andrew Jackson was appointed military governor in March 1821, but he did not arrive in Pensacola until July. He resigned the post in September and returned home in October, having spent just three months in Florida. His successor, William P. Duval, was not appointed until April 1822, and he left for an extended visit to his home in Kentucky before the end of the year. Other official positions in the territory had similar turn-over and absences.[96]

The Seminoles were still a problem for the new government. In early 1822, Capt. John R. Bell, provisional secretary of the Florida territory and temporary agent to the Seminoles, prepared an estimate of the number of Indians in Florida. He reported about 22,000 Indians, and 5,000 slaves held by Indians. He estimated that two-thirds of them were refugees from the Creek War, with no valid claim (in the U.S. view) to Florida. Indian settlements were located in the areas around the Apalachicola River, along the Suwannee River, from there south-eastwards to the Alachua Prairie, and then south-westward to a little north of Tampa Bay.[97]

Officials in Florida were concerned from the beginning about the situation with the Seminoles. Until a treaty was signed establishing a reservation, the Indians were not sure of where they could plant crops and expect to be able to harvest them, and they had to contend with white squatters moving into land they occupied. There was no system for licensing traders, and unlicensed traders were supplying the Seminoles with liquor. However, because of the part-time presence and frequent turnover of territorial officials, meetings with the Seminoles were canceled, postponed, or sometimes held merely to set a time and place for a new meeting.[98]

In 1823, the government decided to settle the Seminole on a reservation in the central part of the territory. A meeting to negotiate a treaty was scheduled for early September 1823 at Moultrie Creek, south of St. Augustine. About 425 Seminole attended the meeting, choosing Neamathla to be their chief representative or Speaker. Under the terms of the treaty negotiated there, the Seminole were forced to go under the protection of the United States and give up all claim to lands in Florida, in exchange for a reservation of about four million acres (16,000 km2). The reservation would run down the middle of the Florida peninsula from just north of present-day Ocala to a line even with the southern end of Tampa Bay. The boundaries were well inland from both coasts, to prevent contact with traders from Cuba and the Bahamas. Neamathla and five other chiefs were allowed to keep their villages along the Apalachicola River.[99]

Under the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, the US was obligated to protect the Seminole as long as they remained law-abiding. The government was supposed to distribute farm implements, cattle and hogs to the Seminole, compensate them for travel and losses involved in relocating to the reservation, and provide rations for a year, until the Seminoles could plant and harvest new crops. The government was also supposed to pay the tribe US$5,000 per year for twenty years and provide an interpreter, a school and a blacksmith for twenty years. In turn, the Seminole had to allow roads to be built across the reservation and had to apprehend and return to US jurisdiction any runaway slaves or other fugitives.[100]

Implementation of the treaty stalled. Fort Brooke, with four companies of infantry, was established on the site of present-day Tampa in early 1824, to show the Seminole that the government was serious about moving them onto the reservation. However, by June James Gadsden, who was the principal author of the treaty and charged with implementing it, was reporting that the Seminole were unhappy with the treaty and were hoping to renegotiate it. Fear of a new war crept in. In July, Governor DuVal mobilized the militia and ordered the Tallahassee and Miccosukee chiefs to meet him in St. Marks. At that meeting, he ordered the Seminole to move to the reservation by October 1, 1824.[101]

The move had not begun, but DuVal began paying the Seminole compensation for the improvements they were having to leave as an incentive to move. He also had the promised rations sent to Fort Brooke on Tampa Bay for distribution. The Seminole finally began moving onto the reservation, but within a year some returned to their former homes between the Suwannee and Apalachicola rivers. By 1826, most of the Seminole had gone to the reservation, but were not thriving. They had to clear and plant new fields, and cultivated fields suffered in a long drought. Some of the tribe were reported to have starved to death. Both Col. George M. Brooke, commander of Fort Brooke, and Governor DuVal wrote to Washington seeking help for the starving Seminole, but the requests got caught up in a debate over whether the people should be moved to west of the Mississippi River. For five months, no additional relief reached the Seminole.[102]

The Seminoles slowly settled into the reservation, although they had isolated clashes with whites. Fort King was built near the reservation agency, at the site of present-day Ocala, and by early 1827 the Army could report that the Seminoles were on the reservation and Florida was peaceful. During the five-year peace, some settlers continued to call for removal. The Seminole were opposed to any such move, and especially to the suggestion that they join their Creek relations. Most whites regarded the Seminole as simply Creeks who had recently moved to Florida, while the Seminole claimed Florida as their home and denied that they had any connection with the Creeks.[103]

The Seminoles and slave catchers argued over the ownership of slaves. New plantations in Florida increased the pool of slaves who could escape to Seminole territory. Worried about the possibility of an Indian uprising and/or a slave rebellion, Governor DuVal requested additional Federal troops for Florida, but in 1828 the US closed Fort King. Short of food and finding the hunting declining on the reservation, the Seminole wandered off to get food. In 1828, Andrew Jackson, the old enemy of the Seminoles, was elected President of the United States. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act he promoted, which was to resolve the problems by moving the Seminole and other tribes west of the Mississippi.[104]

In the spring of 1832, the Seminoles on the reservation were called to a meeting at Payne's Landing on the Oklawaha River. The treaty negotiated there called for the Seminoles to move west, if the land were found to be suitable. They were to settle on the Creek reservation and become part of the Creek tribe. The delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the new reservation did not leave Florida until October 1832. After touring the area for several months and conferring with the Creeks who had already been settled there, the seven chiefs signed a statement on March 28, 1833, that the new land was acceptable. Upon their return to Florida, however, most of the chiefs renounced the statement, claiming that they had not signed it, or that they had been forced to sign it, and in any case, that they did not have the power to decide for all the tribes and bands that resided on the reservation.[105] The villages in the area of the Apalachicola River were more easily persuaded, however, and went west in 1834.[106]

The United States Senate finally ratified the Treaty of Payne's Landing in April 1834. The treaty had given the Seminoles three years to move west of the Mississippi. The government interpreted the three years as starting 1832 and expected the Seminoles to move in 1835. Fort King was reopened in 1834. A new Seminole agent, Wiley Thompson, had been appointed in 1834, and the task of persuading the Seminoles to move fell to him. He called the chiefs together at Fort King in October 1834 to talk to them about the removal to the west. The Seminoles informed Thompson that they had no intention of moving and that they did not feel bound by the Treaty of Payne's Landing. Thompson then requested reinforcements for Fort King and Fort Brooke, reporting that, "the Indians after they had received the Annuity, purchased an unusually large quantity of Powder & Lead." General Clinch also warned Washington that the Seminoles did not intend to move and that more troops would be needed to force them to move. In March 1835, Thompson called the chiefs together to read a letter from Andrew Jackson to them. In his letter, Jackson said, "Should you ... refuse to move, I have then directed the Commanding officer to remove you by force." The chiefs asked for thirty days to respond. A month later, the Seminole chiefs told Thompson that they would not move west. Thompson and the chiefs began arguing, and General Clinch had to intervene to prevent bloodshed. Eventually, eight of the chiefs agreed to move west but asked to delay the move until the end of the year, and Thompson and Clinch agreed.[107]

Five of the most important of the Seminole chiefs, including Micanopy of the Alachua Seminoles, had not agreed to the move. In retaliation, Thompson declared that those chiefs were removed from their positions. As relations with the Seminoles deteriorated, Thompson forbade the sale of guns and ammunition to the Seminoles. Osceola, a young warrior beginning to be noticed particularly by the white settlers, was particularly upset by the ban, feeling that it equated Seminoles with slaves and said, "The white man shall not make me black. I will make the white man red with blood; and then blacken him in the sun and rain ... and the buzzard live upon his flesh." In spite of this, Thompson considered Osceola to be a friend and gave him a rifle. Later, though, when Osceola was causing trouble, Thompson had him locked up at Fort King for a night. The next day, in order to secure his release, Osceola agreed to abide by the Treaty of Payne's Landing and to bring his followers in.[108]

The situation grew worse. On June 19, 1835, a group of whites searching for lost cattle found a group of Indians sitting around a campfire cooking the remains of what they claimed was one of their herd. The whites disarmed and proceeded to whip the Indians, when two more arrived and opened fire on the whites. Three whites were wounded, and one Indian was killed and one wounded, at what became known as the skirmish at Hickory Sink. After complaining to Indian Agent Thompson and not receiving a satisfactory response, the Seminoles became further convinced that they would not receive fair compensations for their complaints of hostile treatment by the settlers. Believed to be in response for the incident at Hickory Sink, in August 1835, Private Kinsley Dalton (for whom Dalton, Georgia, is named) was killed by Seminoles as he was carrying the mail from Fort Brooke to Fort King.[109]

Throughout the summer of 1835, the Seminole who had agreed to leave Florida were gathered at Fort King, as well as other military posts. From these gathering places, they would be sent to Tampa Bay where transports would then take them to New Orleans, destined eventually for reservations out west. However, the Seminole ran into issues getting fair prices for the property they needed to sell (chiefly livestock and slaves). Furthermore, there were issues with furnishing the Seminole with proper clothing. These issues led many Seminoles to think twice about leaving Florida.[110]

In November 1835 Chief Charley Emathla, wanting no part of a war, agreed to removal and sold his cattle at Fort King in preparation for moving his people to Fort Brooke to emigrate to the west. This act was considered a betrayal by other Seminoles who months earlier declared in council that any Seminole chief who sold his cattle would be sentenced to death. Osceola met Charley Emathla on the trail back to his village and killed him, scattering the money from the cattle purchase across his body.[111]

As Florida officials realized the Seminole would resist relocation, preparations for war began. Settlers fled to safety as Seminole attacked plantations and a militia wagon train. Two companies totaling 110 men under the command of Major Francis L. Dade were sent from Fort Brooke to reinforce Fort King in mid-December 1835. On the morning of December 28, the train of troops was ambushed by a group of Seminole warriors under the command of Alligator near modern-day Bushnell, Florida. The entire command and their small cannon were destroyed, with only two badly wounded soldiers surviving to return to Fort Brooke. Over the next few months Generals Clinch, Gaines and Winfield Scott, as well as territorial governor Richard Keith Call, led large numbers of troops in futile pursuits of the Seminoles. In the meantime, the Seminoles struck throughout the state, attacking isolated farms, settlements, plantations and Army forts, even burning the Cape Florida lighthouse. Supply problems and a high rate of illness during the summer caused the Army to abandon several forts.[112]

On Dec. 28, 1835, Major Benjamine A. Putnam with a force of soldiers occupied the Bulow Plantation and fortified it with cotton bales and a stockade. Local planters took refuge with their slaves. The Major abandoned the site on January 23, 1836, and the Bulow Plantation was later burned by the Seminoles. Now a State Park, the site remains a window into the destruction of the conflict; the massive stone ruins of the huge Bulow sugar mill stand little changed from the 1830s. By February 1836 the Seminole and black allies had attacked 21 plantations along the river.

Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock was among those who found the remains of the Dade party in February. In his journal he wrote of the discovery and expressed his discontent:

The government is in the wrong, and this is the chief cause of the persevering opposition of the Indians, who have nobly defended their country against our attempt to enforce a fraudulent treaty. The natives used every means to avoid a war, but were forced into it by the tyranny of our government.[113]

On November 21, 1836, at the Battle of Wahoo Swamp, the Seminole fought against American allied forces numbering 2500, successfully driving them back.; among the American dead was Major David Moniac, the first Native American graduate of West Point.[114] The skirmish restored Seminole confidence, showing their ability to hold their ground against their old enemies the Creek and white settlers.

Late in 1836, Major General Thomas Jesup, US Quartermaster, was placed in command of the war. Jesup brought a new approach to the war. He concentrated on wearing the Seminoles down rather than sending out large groups who were more easily ambushed. He needed a large military presence in the state to control it, and he eventually brought a force of more than 9,000 men into the state under his command. "Letters went off to the governors of the adjacent states calling for regiments of twelve-months volunteers. In stressing his great need, Jesup did not hesitate to mention a fact harrowing to his correspondents. "This is a negro not an Indian war."[115] Resulting in about half of the force volunteering as volunteers and militia. It also included a brigade of Marines, and Navy and Revenue-Marine personnel patrolling the coast and inland rivers and streams.[116]

In January 1837, the Army began to achieve more tangible successes, capturing or killing numerous Indians and blacks. At the end of January, some Seminole chiefs sent messengers to Jesup, and arranged a truce. In March a "Capitulation" was signed by several chiefs, including Micanopy, stipulating that the Seminole could be accompanied by their allies and "their negroes, their bona fide property", in their removal to the West. By the end of May, many chiefs, including Micanopy, had surrendered. Two important leaders, Osceola and Sam Jones (a.k.a. Abiaca, Ar-pi-uck-i, Opoica, Arpeika, Aripeka, Aripeika), had not surrendered, however, and were known to be vehemently opposed to relocation. On June 2 these two leaders with about 200 followers entered the poorly guarded holding camp at Fort Brooke and led away the 700 Seminoles who had surrendered. The war was on again, and Jesup decided against trusting the word of an Indian again. On Jesup's orders, Brigadier General Joseph Marion Hernández commanded an expedition that captured several Indian leaders, including Coacoochee (Wild Cat), John Horse, Osceola and Micanopy when they appeared for conferences under a white flag of truce. Coacoochee and other captives, including John Horse, escaped from their cell at Fort Marion in St. Augustine,[117] but Osceola did not go with them. He died in prison, probably of malaria.[118]

Jesup organized a sweep down the peninsula with multiple columns, pushing the Seminoles further south. On Christmas Day 1837, Colonel Zachary Taylor's column of 800 men encountered a body of about 400 warriors on the north shore of Lake Okeechobee. The Seminole were led by Sam Jones, Alligator and the recently escaped Coacoochee; they were well positioned in a hammock surrounded by sawgrass with half a mile of swamp in front of it. On the far side of the hammock was Lake Okeechobee. Here the saw grass stood five feet high. The mud and water were three feet deep. Horses would be of no use. The Seminole had chosen their battleground. They had sliced the grass to provide an open field of fire and had notched the trees to steady their rifles. Their scouts were perched in the treetops to follow every movement of the troops coming up. As Taylor's army came up to this position, he decided to attack.

At about half past noon, with the sun shining directly overhead and the air still and quiet, Taylor moved his troops squarely into the center of the swamp. His plan was to attack directly rather than try to encircle the Indians. All his men were on foot. In the first line were the Missouri volunteers. As soon as they came within range, the Seminoles opened fire. The volunteers broke, and their commander Colonel Gentry, fatally wounded, was unable to rally them. They fled back across the swamp. The fighting in the saw grass was deadliest for five companies of the Sixth Infantry; every officer but one, and most of their noncoms, were killed or wounded. When those units retired a short distance to re-form, they found only four men of these companies unharmed. The US eventually drove the Seminoles from the hammock, but they escaped across the lake. Taylor lost 26 killed and 112 wounded, while the Seminoles casualties were eleven dead and fourteen wounded. The US claimed the Battle of Lake Okeechobee as a great victory.[119][120]

At the end of January, Jesup's troops caught up with a large body of Seminoles to the east of Lake Okeechobee. Originally positioned in a hammock, the Seminoles were driven across a wide stream by cannon and rocket fire and made another stand. They faded away, having inflicted more casualties than they suffered, and the Battle of Loxahatchee was over. In February 1838, the Seminole chiefs Tuskegee and Halleck Hadjo approached Jesup with the proposal to stop fighting if they could stay in the area south of Lake Okeechobee, rather than relocating west. Jesup favored the idea but had to gain approval from officials in Washington for approval. The chiefs and their followers camped near the Army while awaiting the reply. When the secretary of war rejected the idea, Jesup seized the 500 Indians in the camp, and had them transported to the Indian Territory.[121]

In May, Jesup's request to be relieved of command was granted, and Zachary Taylor assumed command of the Army in Florida. With reduced forces, Taylor concentrated on keeping the Seminole out of northern Florida by building many small posts at twenty-mile (30 km) intervals across the peninsula, connected by a grid of roads. The winter season was fairly quiet, without major actions. In Washington and around the country, support for the war was eroding. Many people began to think the Seminoles had earned the right to stay in Florida. Far from being over, the war had become very costly. President Martin Van Buren sent the Commanding General of the Army, Alexander Macomb, to negotiate a new treaty with the Seminoles. On May 19, 1839, Macomb announced an agreement. In exchange for a reservation in southern Florida, the Seminoles would stop fighting.[122]

As the summer passed, the agreement seemed to be holding. However, on July 23, some 150 Indians attacked a trading post on the Caloosahatchee River; it was guarded by a detachment of 23 soldiers under the command of Colonel William S. Harney. He and some soldiers escaped by the river, but the Seminoles killed most of the garrison, as well as several civilians at the post. Many blamed the "Spanish" Indians, led by Chakaika, for the attack, but others suspected Sam Jones, whose band of Mikasuki had agreed to the treaty with Macomb. Jones, when questioned, promised to turn the men responsible for the attack over to Harney in 33 days. Before that time was up, two soldiers visiting Jones' camp were killed.[123]

The Army turned to bloodhounds to track the Indians, with poor results. Taylor's blockhouse and patrol system in northern Florida kept the Seminoles on the move but could not clear them out. In May 1839, Taylor, having served longer than any preceding commander in the Florida war, was granted his request for a transfer and replaced by Brig. Gen. Walker Keith Armistead. Armistead immediately went on the offensive, actively campaigning during the summer. Seeking hidden camps, the Army also burned fields and drove off livestock: horses, cattle and pigs. By the middle of the summer, the Army had destroyed 500 acres (2.0 km2) of Seminole crops.[124][125]

The Navy sent its sailors and Marines up rivers and streams, and into the Everglades. In late 1839 Navy Lt. John T. McLaughlin was given command of a joint Army-Navy amphibious force to operate in Florida. McLaughlin established his base at Tea Table Key in the upper Florida Keys. Traveling from December 1840 to the middle of January 1841, McLaughlin's force crossed the Everglades from east to west in dugout canoes, the first group of whites to complete a crossing.[126][127] The Seminoles kept out of their way.

Indian Key is a small island in the upper Florida Keys. In 1840, it was the county seat of the newly created Dade County, and a wrecking port. Early in the morning of August 7, 1840, a large party of "Spanish" Indians snuck onto Indian Key. By chance, one man was up and raised the alarm after spotting the Indians. Of about fifty people living on the island, forty were able to escape. The dead included Dr. Henry Perrine, former United States Consul in Campeche, Mexico, who was waiting at Indian Key until it was safe to take up a 36-square mile (93 km2) grant on the mainland that Congress had awarded to him.

The naval base on the Key was manned by a doctor, his patients, and five sailors under a midshipman. They mounted a couple of cannons on barges to attack the Indians. The Indians fired back at the sailors with musket balls loaded in cannon on the shore. The recoil of the cannon broke them loose from the barges, sending them into the water, and the sailors had to retreat. The Indians looted and burned the buildings on Indian Key. In December 1840, Col. Harney at the head of ninety men found Chakaika's camp deep in the Everglades. His force killed the chief and hanged some of the men in his band.[128][129][130]

Armistead received US$55,000 to use for bribing chiefs to surrender. Echo Emathla, a Tallahassee chief, surrendered, but most of the Tallahassee, under Tiger Tail, did not. Coosa Tustenuggee finally accepted US$5,000 for bringing in his 60 people. Lesser chiefs received US$200, and every warrior got US$30 and a rifle. By the spring of 1841, Armistead had sent 450 Seminoles west. Another 236 were at Fort Brooke awaiting transportation. Armistead estimated that 120 warriors had been shipped west during his tenure and that no more than 300 warriors remained in Florida.[131]

In May 1841, Armistead was replaced by Col. William Jenkins Worth as commander of Army forces in Florida. Worth had to cut back on the unpopular war: he released nearly 1,000 civilian employees and consolidated commands. Worth ordered his men out on "search and destroy" missions during the summer and drove the Seminoles out of much of northern Florida.[132]

The Army's actions became a war of attrition; some Seminole surrendered to avoid starvation. Others were seized when they came in to negotiate surrender, including, for the second time, Coacoochee. A large bribe secured Coacoochee's cooperation in persuading others to surrender.[133][134]

In the last action of the war, General William Bailey and prominent planter Jack Bellamy led a posse of 52 men on a three-day pursuit of a small band of Tiger Tail's braves who had been attacking settlers, surprising their swampy encampment and killing all 24. William Wesley Hankins, at sixteen the youngest of the posse, accounted for the last of the kills and was acknowledged as having fired the last shot of the Second Seminole War.[135]

After Colonel Worth recommended early in 1842 that the remaining Seminoles be left in peace, he received authorization to leave the remaining Seminoles on an informal reservation in southwestern Florida and to declare an end to the war.,[136] He announced it on August 14, 1842. In the same month, Congress passed the Armed Occupation Act, which provided free land to settlers who improved the land and were prepared to defend themselves from Indians. At the end of 1842, the remaining Indians in Florida living outside the reservation in southwest Florida were rounded up and shipped west. By April 1843, the Army presence in Florida had been reduced to one regiment. By November 1843, Worth reported that only about 95 Seminole men and some 200 women and children living on the reservation were left, and that they were no longer a threat.[137]

The Second Seminole War may have cost as much as $40,000,000. More than 40,000 regular U.S. military, militiamen and volunteers served in the war. This Indian war cost the lives of 1,500 soldiers, mostly from disease. It is estimated that more than 300 regular U.S. Army, Navy and Marine Corps personnel were killed in action, along with 55 volunteers.[138] There is no record of the number of Seminole killed in action, but many homes and Indian lives were lost. A great many Seminole died of disease or starvation in Florida, on the journey west, and after they reached Indian Territory. An unknown but apparently substantial number of white civilians were killed by Seminole during the war.[139]

Peace had come to Florida. The Indians were mostly staying on the reservation. Groups of ten or so men would visit Tampa to trade. Squatters were moving closer to the reservation, however, and in 1845 President James Polk established a 20-mile (32 km) wide buffer zone around the reservation. No land could be claimed within the buffer zone, no title would be issued for land there, and the U.S. Marshal would remove squatters from the buffer zone upon request. In 1845, Thomas P. Kennedy, who operated a store at Fort Brooke, converted his fishing station on Pine Island into a trading post for the Indians. The post did not do well, however, because whites who sold whiskey to the Indians told them that they would be seized and sent west if they went to Kennedy's store.[140]

The Florida authorities continued to press for removal of all Indians from Florida. The Indians for their part tried to limit their contacts with whites as much as possible. In 1846, Captain John T. Sprague was placed in charge of Indian affairs in Florida. He had great difficulty in getting the chiefs to meet with him. They were very distrustful of the Army since it had often seized chiefs while under a flag of truce. He did manage to meet with all of the chiefs in 1847, while investigating a report of a raid on a farm. He reported that the Indians in Florida then consisted of 120 warriors, including seventy Seminoles in Billy Bowlegs' band, thirty Mikasukis in Sam Jones' band, twelve Creeks (Muscogee speakers) in Chipco's band, 4 Yuchis and 4 Choctaws. He also estimated that there were 100 women and 140 children.[141]

The trading post on Pine Island had burned down in 1848, and in 1849 Thomas Kennedy and his new partner, John Darling, were given permission to open a trading post on what is now Paynes Creek, a tributary of the Peace River. One band of Indians was living outside the reservation at this time. Called "outsiders", it consisted of twenty warriors under the leadership of Chipco, and included five Muscogees, seven Mikasukis, six Seminoles, one Creek and one Yuchi. On July 12, 1849, four members of this band attacked a farm on the Indian River just north of Fort Pierce, killing one man and wounding another man and a woman. The news of this raid caused much of the population of the east coast of Florida to flee to St. Augustine. On July 17, four of the "outsiders" who had attacked the farm on the Indian River, plus a fifth man who had not been at Indian River, attacked the Kennedy and Darling store. Two workers at the store, including a Captain Payne, were killed, and another worker and his wife were wounded as they escorted their child into hiding.[142]

The U.S. Army was not prepared to engage the Indians. It had few men stationed in Florida and no means to move them quickly to where they could protect the white settlers and capture the Indians. The War Department began a new buildup in Florida, placing Major General David E. Twiggs in command, and the state called up two companies of mounted volunteers to guard settlements. Captain John Casey, who was in charge of the effort to move the Indians west, was able to arrange a meeting between General Twiggs and several of the Indian leaders at Charlotte Harbor. At that meeting, Billy Bowlegs promised, with the approval of other leaders, to deliver the five men responsible for the attacks to the Army within thirty days. On October 18, Bowlegs delivered three of the men to Twiggs, along with the severed hand of another who had been killed while trying to escape. The fifth man had been captured but had escaped.[143]