Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life.[1] The entomologist E. O. Wilson characterised parasites as "predators that eat prey in units of less than one".[2] Parasites include single-celled protozoans such as the agents of malaria, sleeping sickness, and amoebic dysentery; animals such as hookworms, lice, mosquitoes, and vampire bats; fungi such as honey fungus and the agents of ringworm; and plants such as mistletoe, dodder, and the broomrapes.

There are six major parasitic strategies of exploitation of animal hosts, namely parasitic castration, directly transmitted parasitism (by contact), trophically-transmitted parasitism (by being eaten), vector-transmitted parasitism, parasitoidism, and micropredation. One major axis of classification concerns invasiveness: an endoparasite lives inside the host's body; an ectoparasite lives outside, on the host's surface.

Like predation, parasitism is a type of consumer–resource interaction,[3] but unlike predators, parasites, with the exception of parasitoids, are typically much smaller than their hosts, do not kill them, and often live in or on their hosts for an extended period. Parasites of animals are highly specialised, and reproduce at a faster rate than their hosts. Classic examples include interactions between vertebrate hosts and tapeworms, flukes, the malaria-causing Plasmodium species, and fleas.

Паразиты снижают приспособленность хозяина посредством общей или специализированной патологии , от паразитарной кастрации до модификации поведения хозяина. Паразиты повышают собственную приспособленность, эксплуатируя хозяев для получения ресурсов, необходимых для их выживания, в частности, питаясь ими и используя промежуточных (вторичных) хозяев для содействия их передаче от одного окончательного (первичного) хозяина к другому. Хотя паразитизм часто недвусмыслен, он является частью спектра взаимодействий между видами , переходя через паразитоидизм в хищничество, через эволюцию в мутуализм , а у некоторых грибов переходя в сапрофитию .

Люди знали о паразитах, таких как круглые черви и ленточные черви , со времен Древнего Египта , Греции и Рима . В ранние современные времена Антони ван Левенгук наблюдал Giardia lamblia в свой микроскоп в 1681 году, в то время как Франческо Реди описал внутренних и внешних паразитов, включая овечью двуустку и клещей . Современная паразитология развилась в 19 веке. В человеческой культуре паразитизм имеет негативные коннотации. Они были использованы в сатирическом эффекте в поэме Джонатана Свифта 1733 года «О поэзии: Рапсодия», где поэты сравнивались с гиперпаразитарными «вредителями». В художественной литературе готический роман ужасов Брэма Стокера 1897 года «Дракула» и его многочисленные более поздние адаптации изображали кровососущего паразита. Фильм Ридли Скотта 1979 года «Чужой» был одним из многих произведений научной фантастики , в которых фигурировал паразитический инопланетный вид. [4]

Впервые использованное в английском языке в 1539 году, слово parasite происходит от средневекового французского parasite , от латинизированной формы parasitus , от древнегреческого παράσιτος [5] (parasitos) «тот, кто ест за столом другого», в свою очередь от παρά [6] (para) «рядом, около» и σῖτος (sitos) «пшеница, еда». [7] Родственный термин parasitism появляется в английском языке с 1611 года. [8]

Parasitism is a kind of symbiosis, a close and persistent long-term biological interaction between a parasite and its host. Unlike saprotrophs, parasites feed on living hosts, though some parasitic fungi, for instance, may continue to feed on hosts they have killed. Unlike commensalism and mutualism, the parasitic relationship harms the host, either feeding on it or, as in the case of intestinal parasites, consuming some of its food. Because parasites interact with other species, they can readily act as vectors of pathogens, causing disease.[9][10][11] Predation is by definition not a symbiosis, as the interaction is brief, but the entomologist E. O. Wilson has characterised parasites as "predators that eat prey in units of less than one".[2]

Within that scope are many possible strategies. Taxonomists classify parasites in a variety of overlapping schemes, based on their interactions with their hosts and on their life cycles, which are sometimes very complex. An obligate parasite depends completely on the host to complete its life cycle, while a facultative parasite does not. Parasite life cycles involving only one host are called "direct"; those with a definitive host (where the parasite reproduces sexually) and at least one intermediate host are called "indirect".[12][13] An endoparasite lives inside the host's body; an ectoparasite lives outside, on the host's surface.[14] Mesoparasites—like some copepods, for example—enter an opening in the host's body and remain partly embedded there.[15] Some parasites can be generalists, feeding on a wide range of hosts, but many parasites, and the majority of protozoans and helminths that parasitise animals, are specialists and extremely host-specific.[14] An early basic, functional division of parasites distinguished microparasites and macroparasites. These each had a mathematical model assigned in order to analyse the population movements of the host–parasite groupings.[16] The microorganisms and viruses that can reproduce and complete their life cycle within the host are known as microparasites. Macroparasites are the multicellular organisms that reproduce and complete their life cycle outside of the host or on the host's body.[16][17]

Much of the thinking on types of parasitism has focused on terrestrial animal parasites of animals, such as helminths. Those in other environments and with other hosts often have analogous strategies. For example, the snubnosed eel is probably a facultative endoparasite (i.e., it is semiparasitic) that opportunistically burrows into and eats sick and dying fish.[18] Plant-eating insects such as scale insects, aphids, and caterpillars closely resemble ectoparasites, attacking much larger plants; they serve as vectors of bacteria, fungi and viruses which cause plant diseases. As female scale insects cannot move, they are obligate parasites, permanently attached to their hosts.[16]

The sensory inputs that a parasite employs to identify and approach a potential host are known as "host cues". Such cues can include, for example, vibration,[19] exhaled carbon dioxide, skin odours, visual and heat signatures, and moisture.[20] Parasitic plants can use, for example, light, host physiochemistry, and volatiles to recognize potential hosts.[21]

There are six major parasitic strategies, namely parasitic castration; directly transmitted parasitism; trophically-transmitted parasitism; vector-transmitted parasitism; parasitoidism; and micropredation. These apply to parasites whose hosts are plants as well as animals.[16][22] These strategies represent adaptive peaks; intermediate strategies are possible, but organisms in many different groups have consistently converged on these six, which are evolutionarily stable.[22]

A perspective on the evolutionary options can be gained by considering four key questions: the effect on the fitness of a parasite's hosts; the number of hosts they have per life stage; whether the host is prevented from reproducing; and whether the effect depends on intensity (number of parasites per host). From this analysis, the major evolutionary strategies of parasitism emerge, alongside predation.[23]

Parasitic castrators partly or completely destroy their host's ability to reproduce, diverting the energy that would have gone into reproduction into host and parasite growth, sometimes causing gigantism in the host. The host's other systems remain intact, allowing it to survive and to sustain the parasite.[22][24] Parasitic crustaceans such as those in the specialised barnacle genus Sacculina specifically cause damage to the gonads of their many species[25] of host crabs. In the case of Sacculina, the testes of over two-thirds of their crab hosts degenerate sufficiently for these male crabs to develop female secondary sex characteristics such as broader abdomens, smaller claws and egg-grasping appendages. Various species of helminth castrate their hosts (such as insects and snails). This may happen directly, whether mechanically by feeding on their gonads, or by secreting a chemical that destroys reproductive cells; or indirectly, whether by secreting a hormone or by diverting nutrients. For example, the trematode Zoogonus lasius, whose sporocysts lack mouths, castrates the intertidal marine snail Tritia obsoleta chemically, developing in its gonad and killing its reproductive cells.[24][26]

Directly transmitted parasites, not requiring a vector to reach their hosts, include such parasites of terrestrial vertebrates as lice and mites; marine parasites such as copepods and cyamid amphipods; monogeneans; and many species of nematodes, fungi, protozoans, bacteria, and viruses. Whether endoparasites or ectoparasites, each has a single host-species. Within that species, most individuals are free or almost free of parasites, while a minority carry a large number of parasites; this is known as an aggregated distribution.[22]

Трофически передаваемые паразиты передаются через поедание хозяином. К ним относятся трематоды (все, кроме шистосом ), цестоды , скребни , пентастомиды , многие круглые черви и многие простейшие, такие как токсоплазма . [22] У них сложные жизненные циклы, включающие хозяев двух или более видов. На ювенильных стадиях они заражают и часто инцистируют промежуточного хозяина. Когда промежуточное животное-хозяин съедается хищником, окончательным хозяином, паразит переживает процесс пищеварения и созревает во взрослую особь; некоторые живут как кишечные паразиты . Многие трофически передаваемые паразиты изменяют поведение своих промежуточных хозяев, увеличивая их шансы быть съеденными хищником. Как и в случае с напрямую передаваемыми паразитами, распределение трофически передаваемых паразитов среди особей хозяина является агрегированным. [22] Коинфекция несколькими паразитами является обычным явлением. [27] Аутоинфекция , при которой (в виде исключения) весь жизненный цикл паразита происходит в одном первичном хозяине, иногда может происходить у гельминтов, таких как Strongyloides stercoralis . [28]

Паразиты , передающиеся через переносчиков, полагаются на третью сторону, промежуточного хозяина, где паразит не размножается половым путем, [14] чтобы переносить их от одного окончательного хозяина к другому. [22] Эти паразиты представляют собой микроорганизмы, а именно простейшие , бактерии или вирусы , часто внутриклеточные патогены (возбудители болезней). [22] Их переносчиками в основном являются гематофагические членистоногие, такие как блохи, вши, клещи и комары. [22] [29] Например, олений клещ Ixodes scapularis выступает в качестве переносчика таких заболеваний, как болезнь Лайма , бабезиоз и анаплазмоз . [30] Простейшие эндопаразиты, такие как малярийные паразиты рода Plasmodium и паразиты сонной болезни рода Trypanosoma , имеют инфекционные стадии в крови хозяина, которые переносятся к новым хозяевам через укусы насекомых. [31]

Parasitoids are insects which sooner or later kill their hosts, placing their relationship close to predation.[32] Most parasitoids are parasitoid wasps or other hymenopterans; others include dipterans such as phorid flies. They can be divided into two groups, idiobionts and koinobionts, differing in their treatment of their hosts.[33]

Idiobiont parasitoids sting their often-large prey on capture, either killing them outright or paralysing them immediately. The immobilised prey is then carried to a nest, sometimes alongside other prey if it is not large enough to support a parasitoid throughout its development. An egg is laid on top of the prey and the nest is then sealed. The parasitoid develops rapidly through its larval and pupal stages, feeding on the provisions left for it.[33]

Koinobiont parasitoids, which include flies as well as wasps, lay their eggs inside young hosts, usually larvae. These are allowed to go on growing, so the host and parasitoid develop together for an extended period, ending when the parasitoids emerge as adults, leaving the prey dead, eaten from inside. Some koinobionts regulate their host's development, for example preventing it from pupating or making it moult whenever the parasitoid is ready to moult. They may do this by producing hormones that mimic the host's moulting hormones (ecdysteroids), or by regulating the host's endocrine system.[33]

Микрохищник нападает на более чем одного хозяина, по крайней мере, на небольшую величину снижая приспособленность каждого хозяина, и контактирует с любым одним хозяином только периодически. Такое поведение делает микрохищников подходящими переносчиками, поскольку они могут передавать более мелких паразитов от одного хозяина к другому. [22] [34] [23] Большинство микрохищников являются гематофагами , питающимися кровью. К ним относятся кольчатые черви, такие как пиявки , ракообразные, такие как бранхиуры и изоподы гнатииды , различные двукрылые, такие как комары и мухи цеце , другие членистоногие, такие как блохи и клещи, позвоночные, такие как миноги , и млекопитающие, такие как летучие мыши-вампиры . [22]

Паразиты используют различные методы заражения животных-хозяев, включая физический контакт, фекально-оральный путь , свободноживущие инфекционные стадии и векторы, подходящие для их различных хозяев, жизненных циклов и экологических контекстов. [35] Примеры, иллюстрирующие некоторые из многих возможных комбинаций, приведены в таблице.

Среди многочисленных вариаций паразитических стратегий можно выделить гиперпаразитизм, [37] социальный паразитизм, [38] выводковый паразитизм, [39] клептопаразитизм, [40] половой паразитизм, [41] и адельфопаразитизм. [42]

Гиперпаразиты питаются другим паразитом, как показано на примере простейших, живущих в гельминтных паразитах, [37] или факультативных или облигатных паразитоидах, хозяевами которых являются либо обычные паразиты, либо паразитоиды. [22] [33] Уровни паразитизма за пределами вторичного также встречаются, особенно среди факультативных паразитоидов. В системах галлов дуба может быть до пяти уровней паразитизма. [43]

Гиперпаразиты могут контролировать популяции своих хозяев и используются для этой цели в сельском хозяйстве и в некоторой степени в медицине . Контролирующие эффекты можно увидеть в том, как вирус CHV1 помогает контролировать ущерб, который каштановая гниль , Cryphonectria parasitica , наносит американским каштанам , и в том, как бактериофаги могут ограничивать бактериальные инфекции. Вероятно, хотя и мало исследовано, что большинство патогенных микропаразитов имеют гиперпаразитов, которые могут оказаться широко полезными как в сельском хозяйстве, так и в медицине. [44]

Социальные паразиты используют в своих интересах межвидовые взаимодействия между членами эусоциальных животных, такими как муравьи , термиты и шмели . Примерами служат большая голубая бабочка Phengaris arion , личинки которой используют мимикрию муравьев для паразитирования на определенных муравьях, [38] Bombus bohemicus , шмель, который вторгается в ульи других пчел и берет на себя воспроизводство, пока их детеныши выращиваются рабочими-хозяевами, и Melipona scutellaris , эусоциальная пчела, чьи неплодные королевы избегают рабочих-убийц и вторгаются в другую колонию без королевы. [45] Крайний пример межвидового социального паразитизма обнаружен у муравья Tetramorium inquilinum , облигатного паразита, который живет исключительно на спинах других муравьев Tetramorium . [46] Механизм эволюции социального паразитизма был впервые предложен Карло Эмери в 1909 году. [47] Теперь известный как « правило Эмери », он гласит, что социальные паразиты, как правило, тесно связаны со своими хозяевами, часто принадлежа к одному и тому же роду. [48] [49] [50]

Внутривидовой социальный паразитизм происходит при паразитическом вскармливании, когда некоторые детеныши берут молоко у неродственных самок. У клиновидных капуцинов самки с более высоким рангом иногда берут молоко у самок с более низким рангом без какой-либо взаимности. [51]

In brood parasitism, the hosts act as parents as they raise the young as their own. Brood parasites include birds in different families such as cowbirds, whydahs, cuckoos, and black-headed ducks. These do not build nests of their own, but leave their eggs in nests of other species. The eggs of some brood parasites mimic those of their hosts, while some cowbird eggs have tough shells, making them hard for the hosts to kill by piercing, both mechanisms implying selection by the hosts against parasitic eggs.[39][52][53] The adult female European cuckoo further mimics a predator, the European sparrowhawk, giving her time to lay her eggs in the host's nest unobserved.[54]

In kleptoparasitism (from Greek κλέπτης (kleptēs), "thief"), parasites steal food gathered by the host. The parasitism is often on close relatives, whether within the same species or between species in the same genus or family. For instance, the many lineages of cuckoo bees lay their eggs in the nest cells of other bees in the same family.[40] Kleptoparasitism is uncommon generally but conspicuous in birds; some such as skuas are specialised in pirating food from other seabirds, relentlessly chasing them down until they disgorge their catch.[55]

A unique approach is seen in some species of anglerfish, such as Ceratias holboelli, where the males are reduced to tiny sexual parasites, wholly dependent on females of their own species for survival, permanently attached below the female's body, and unable to fend for themselves. The female nourishes the male and protects him from predators, while the male gives nothing back except the sperm that the female needs to produce the next generation.[41]

Adelphoparasitism, (from Greek ἀδελφός (adelphós), brother[56]), also known as sibling-parasitism, occurs where the host species is closely related to the parasite, often in the same family or genus.[42] In the citrus blackfly parasitoid, Encarsia perplexa, unmated females may lay haploid eggs in the fully developed larvae of their own species, producing male offspring,[57] while the marine worm Bonellia viridis has a similar reproductive strategy, although the larvae are planktonic.[58]

Examples of the major variant strategies are illustrated.

Parasitism has an extremely wide taxonomic range, including animals, plants, fungi, protozoans, bacteria, and viruses.[59]

Parasitism is widespread in the animal kingdom,[63] and has evolved independently from free-living forms hundreds of times.[22] Many types of helminth including flukes and cestodes have complete life cycles involving two or more hosts. By far the largest group is the parasitoid wasps in the Hymenoptera.[22] The phyla and classes with the largest numbers of parasitic species are listed in the table. Numbers are conservative minimum estimates. The columns for Endo- and Ecto-parasitism refer to the definitive host, as documented in the Vertebrate and Invertebrate columns.[60]

A hemiparasite or partial parasite such as mistletoe derives some of its nutrients from another living plant, whereas a holoparasite such as dodder derives all of its nutrients from another plant.[64] Parasitic plants make up about one per cent of angiosperms and are in almost every biome in the world.[65][66][67] All these plants have modified roots, haustoria, which penetrate the host plants, connecting them to the conductive system—either the xylem, the phloem, or both. This provides them with the ability to extract water and nutrients from the host. A parasitic plant is classified depending on where it latches onto the host, either the stem or the root, and the amount of nutrients it requires. Since holoparasites have no chlorophyll and therefore cannot make food for themselves by photosynthesis, they are always obligate parasites, deriving all their food from their hosts.[66] Some parasitic plants can locate their host plants by detecting chemicals in the air or soil given off by host shoots or roots, respectively. About 4,500 species of parasitic plant in approximately 20 families of flowering plants are known.[68][66]

Species within the Orobanchaceae (broomrapes) are among the most economically destructive of all plants. Species of Striga (witchweeds) are estimated to cost billions of dollars a year in crop yield loss, infesting over 50 million hectares of cultivated land within Sub-Saharan Africa alone. Striga infects both grasses and grains, including corn, rice, and sorghum, which are among the world's most important food crops. Orobanche also threatens a wide range of other important crops, including peas, chickpeas, tomatoes, carrots, and varieties of cabbage. Yield loss from Orobanche can be total; despite extensive research, no method of control has been entirely successful.[69]

Many plants and fungi exchange carbon and nutrients in mutualistic mycorrhizal relationships. Some 400 species of myco-heterotrophic plants, mostly in the tropics, however effectively cheat by taking carbon from a fungus rather than exchanging it for minerals. They have much reduced roots, as they do not need to absorb water from the soil; their stems are slender with few vascular bundles, and their leaves are reduced to small scales, as they do not photosynthesize. Their seeds are very small and numerous, so they appear to rely on being infected by a suitable fungus soon after germinating.[70]

Parasitic fungi derive some or all of their nutritional requirements from plants, other fungi, or animals.

Plant pathogenic fungi are classified into three categories depending on their mode of nutrition: biotrophs, hemibiotrophs and necrotrophs. Biotrophic fungi derive nutrients from living plant cells, and during the course of infection they colonise their plant host in such a way as to keep it alive for a maximally long time.[71] One well-known example of a biotrophic pathogen is Ustilago maydis, causative agent of the corn smut disease. Necrotrophic pathogens on the other hand, kill host cells and feed saprophytically, an example being the root-colonising honey fungi in the genus Armillaria.[72] Hemibiotrophic pathogens begin their colonising their hosts as biotrophs, and subsequently killing off host cells and feeding as necrotrophs, a phenomenon termed the biotrophy-necrotrophy switch.[73]

Pathogenic fungi are well-known causative agents of diseases on animals as well as humans. Fungal infections (mycosis) are estimated to kill 1.6 million people each year.[74] One example of a potent fungal animal pathogen are Microsporidia - obligate intracellular parasitic fungi that largely affect insects, but may also affect vertebrates including humans, causing the intestinal infection microsporidiosis.[75]

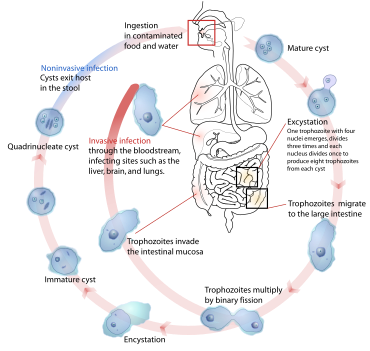

Protozoa such as Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, and Entamoeba[76] are endoparasitic. They cause serious diseases in vertebrates including humans—in these examples, malaria, sleeping sickness, and amoebic dysentery—and have complex life cycles.[31]

Many bacteria are parasitic, though they are more generally thought of as pathogens causing disease.[77] Parasitic bacteria are extremely diverse, and infect their hosts by a variety of routes. To give a few examples, Bacillus anthracis, the cause of anthrax, is spread by contact with infected domestic animals; its spores, which can survive for years outside the body, can enter a host through an abrasion or may be inhaled. Borrelia, the cause of Lyme disease and relapsing fever, is transmitted by vectors, ticks of the genus Ixodes, from the diseases' reservoirs in animals such as deer. Campylobacter jejuni, a cause of gastroenteritis, is spread by the fecal–oral route from animals, or by eating insufficiently cooked poultry, or by contaminated water. Haemophilus influenzae, an agent of bacterial meningitis and respiratory tract infections such as influenza and bronchitis, is transmitted by droplet contact. Treponema pallidum, the cause of syphilis, is spread by sexual activity.[78]

Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites, characterised by extremely limited biological function, to the point where, while they are evidently able to infect all other organisms from bacteria and archaea to animals, plants and fungi, it is unclear whether they can themselves be described as living. They can be either RNA or DNA viruses consisting of a single or double strand of genetic material (RNA or DNA, respectively), covered in a protein coat and sometimes a lipid envelope. They thus lack all the usual machinery of the cell such as enzymes, relying entirely on the host cell's ability to replicate DNA and synthesise proteins. Most viruses are bacteriophages, infecting bacteria.[79][80][81][82]

Parasitism is a major aspect of evolutionary ecology; for example, almost all free-living animals are host to at least one species of parasite. Vertebrates, the best-studied group, are hosts to between 75,000 and 300,000 species of helminths and an uncounted number of parasitic microorganisms. On average, a mammal species hosts four species of nematode, two of trematodes, and two of cestodes.[83] Humans have 342 species of helminth parasites, and 70 species of protozoan parasites.[84] Some three-quarters of the links in food webs include a parasite, important in regulating host numbers. Perhaps 40 per cent of described species are parasitic.[83]

Parasitism is hard to demonstrate from the fossil record, but holes in the mandibles of several specimens of Tyrannosaurus may have been caused by Trichomonas-like parasites.[85] Saurophthirus, the Early Cretaceous flea, parasitized pterosaurs.[86][87] Eggs that belonged to nematode worms and probably protozoan cysts were found in the Late Triassic coprolite of phytosaur. This rare find in Thailand reveals more about the ecology of prehistoric parasites.[88]

As hosts and parasites evolve together, their relationships often change. When a parasite is in a sole relationship with a host, selection drives the relationship to become more benign, even mutualistic, as the parasite can reproduce for longer if its host lives longer.[89] But where parasites are competing, selection favours the parasite that reproduces fastest, leading to increased virulence. There are thus varied possibilities in host–parasite coevolution.[90]

Evolutionary epidemiology analyses how parasites spread and evolve, whereas Darwinian medicine applies similar evolutionary thinking to non-parasitic diseases like cancer and autoimmune conditions.[91]

Long-term coevolution sometimes leads to a relatively stable relationship tending to commensalism or mutualism, as, all else being equal, it is in the evolutionary interest of the parasite that its host thrives. A parasite may evolve to become less harmful for its host or a host may evolve to cope with the unavoidable presence of a parasite—to the point that the parasite's absence causes the host harm. For example, although animals parasitised by worms are often clearly harmed, such infections may also reduce the prevalence and effects of autoimmune disorders in animal hosts, including humans.[89] In a more extreme example, some nematode worms cannot reproduce, or even survive, without infection by Wolbachia bacteria.[92]

Lynn Margulis and others have argued, following Peter Kropotkin's 1902 Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, that natural selection drives relationships from parasitism to mutualism when resources are limited. This process may have been involved in the symbiogenesis which formed the eukaryotes from an intracellular relationship between archaea and bacteria, though the sequence of events remains largely undefined.[93][94]

Competition between parasites can be expected to favour faster reproducing and therefore more virulent parasites, by natural selection.[90][95]

.jpg/440px-Pink_Flamingos_with_Duck_-_Camargue,_France_-_April_2007_(cropped).jpg)

Among competing parasitic insect-killing bacteria of the genera Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, virulence depended on the relative potency of the antimicrobial toxins (bacteriocins) produced by the two strains involved. When only one bacterium could kill the other, the other strain was excluded by the competition. But when caterpillars were infected with bacteria both of which had toxins able to kill the other strain, neither strain was excluded, and their virulence was less than when the insect was infected by a single strain.[90]

A parasite sometimes undergoes cospeciation with its host, resulting in the pattern described in Fahrenholz's rule, that the phylogenies of the host and parasite come to mirror each other.[96]

An example is between the simian foamy virus (SFV) and its primate hosts. The phylogenies of SFV polymerase and the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit II from African and Asian primates were found to be closely congruent in branching order and divergence times, implying that the simian foamy viruses cospeciated with Old World primates for at least 30 million years.[97]

The presumption of a shared evolutionary history between parasites and hosts can help elucidate how host taxa are related. For instance, there has been a dispute about whether flamingos are more closely related to storks or ducks. The fact that flamingos share parasites with ducks and geese was initially taken as evidence that these groups were more closely related to each other than either is to storks. However, evolutionary events such as the duplication, or the extinction of parasite species (without similar events on the host phylogeny) often erode similarities between host and parasite phylogenies. In the case of flamingos, they have similar lice to those of grebes. Flamingos and grebes do have a common ancestor, implying cospeciation of birds and lice in these groups. Flamingo lice then switched hosts to ducks, creating the situation which had confused biologists.[98]

.jpg/440px-Toxoplasma_gondii_(2).jpg)

Паразиты заражают симпатрических хозяев (находящихся в пределах их географической области) более эффективно, как было показано на примере дигенетических трематод , заражающих озерных улиток. [99] Это соответствует гипотезе Красной Королевы , которая гласит, что взаимодействие между видами приводит к постоянному естественному отбору для коадаптации. Паразиты отслеживают фенотипы местных хозяев, поэтому паразиты менее заразны для аллопатрических хозяев, которые находятся в других географических регионах. [99]

Некоторые паразиты изменяют поведение хозяина , чтобы увеличить свою передачу между хозяевами, часто в отношении хищника и добычи ( паразит усиливает трофическую передачу ). Например, в прибрежном солончаке Калифорнии трематода Euhaplorchis californiensis снижает способность своего хозяина -киллифа избегать хищников. [100] Этот паразит созревает в белых цаплях , которые с большей вероятностью питаются инфицированными киллифами, чем незараженной рыбой. Другим примером является простейшее Toxoplasma gondii , паразит, который созревает в кошках , но может переноситься многими другими млекопитающими . Неинфицированные крысы избегают запахов кошек, но крысы, инфицированные T. gondii , привлекаются этим запахом, что может увеличить передачу хозяевам-кошкам. [101] Малярийный паразит изменяет запах кожи своих хозяев-людей, увеличивая их привлекательность для комаров и, следовательно, повышая вероятность передачи паразита. [36] Паук Cyclosa argenteoalba часто имеет прикрепленных к ним личинок паразитоидных ос, которые изменяют их поведение при строительстве паутины. Вместо того, чтобы производить свои обычные липкие спиралевидные паутины, они создавали упрощенные паутины, когда паразиты были прикреплены. Это измененное поведение длилось дольше и было тем заметнее, чем дольше паразиты оставались на пауках. [102]

Паразиты могут эксплуатировать своих хозяев для выполнения ряда функций, которые им в противном случае пришлось бы выполнять самим. Паразиты, которые теряют эти функции, затем получают селективное преимущество, поскольку они могут перенаправлять ресурсы на воспроизводство. Многие эктопаразиты насекомых, включая клопов , клопов-летучих мышей , вшей и блох, утратили способность летать , полагаясь вместо этого на своих хозяев для транспортировки. [103] Потеря признаков в целом широко распространена среди паразитов. [104] Ярким примером является миксоспоридий Henneguya zschokkei , эктопаразит рыб и единственное животное, которое, как известно, утратило способность к аэробному дыханию: в его клетках отсутствуют митохондрии . [105]

Хозяева выработали множество защитных мер против своих паразитов, включая физические барьеры, такие как кожа позвоночных [106] , иммунная система млекопитающих [107] , насекомые, активно удаляющие паразитов [108] , и защитные химические вещества в растениях [109] .

Эволюционный биолог У. Д. Гамильтон предположил, что половое размножение могло развиться, чтобы помочь победить множественных паразитов, обеспечивая генетическую рекомбинацию , перетасовку генов для создания различных комбинаций. Гамильтон показал с помощью математического моделирования, что половое размножение будет эволюционно стабильным в различных ситуациях, и что предсказания теории соответствуют фактической экологии полового размножения. [110] [111] Однако может существовать компромисс между иммунокомпетентностью и размножением вторичных половых признаков самцов позвоночных хозяев , таких как оперение павлинов и гривы львов . Это происходит потому, что мужской гормон тестостерон стимулирует рост вторичных половых признаков, благоприятствуя таким самцам в половом отборе , ценой снижения их иммунной защиты. [112]

.jpg/440px-Short_Horned_Lizard_(4457945238).jpg)

The physical barrier of the tough and often dry and waterproof skin of reptiles, birds and mammals keeps invading microorganisms from entering the body. Human skin also secretes sebum, which is toxic to most microorganisms.[106] On the other hand, larger parasites such as trematodes detect chemicals produced by the skin to locate their hosts when they enter the water. Vertebrate saliva and tears contain lysozyme, an enzyme that breaks down the cell walls of invading bacteria.[106] Should the organism pass the mouth, the stomach with its hydrochloric acid, toxic to most microorganisms, is the next line of defence.[106] Some intestinal parasites have a thick, tough outer coating which is digested slowly or not at all, allowing the parasite to pass through the stomach alive, at which point they enter the intestine and begin the next stage of their life. Once inside the body, parasites must overcome the immune system's serum proteins and pattern recognition receptors, intracellular and cellular, that trigger the adaptive immune system's lymphocytes such as T cells and antibody-producing B cells. These have receptors that recognise parasites.[107]

Insects often adapt their nests to reduce parasitism. For example, one of the key reasons why the wasp Polistes canadensis nests across multiple combs, rather than building a single comb like much of the rest of its genus, is to avoid infestation by tineid moths. The tineid moth lays its eggs within the wasps' nests and then these eggs hatch into larvae that can burrow from cell to cell and prey on wasp pupae. Adult wasps attempt to remove and kill moth eggs and larvae by chewing down the edges of cells, coating the cells with an oral secretion that gives the nest a dark brownish appearance.[108]

Растения реагируют на атаку паразита серией химических защит, таких как полифенолоксидаза , под контролем сигнальных путей жасмоновой кислоты, нечувствительной (JA) и салициловой кислоты (SA). [109] [113] Различные биохимические пути активируются различными атаками, и эти два пути могут взаимодействовать положительно или отрицательно. В целом, растения могут инициировать либо специфический, либо неспецифический ответ. [114] [113] Специфические ответы включают распознавание паразита клеточными рецепторами растения, что приводит к сильному, но локализованному ответу: защитные химикаты вырабатываются вокруг области, где был обнаружен паразит, блокируя его распространение и избегая напрасной траты защитного производства там, где это не нужно. [114] Неспецифические защитные ответы являются системными, что означает, что ответы не ограничиваются областью растения, а распространяются по всему растению, что делает их затратными с точки зрения энергии. Они эффективны против широкого спектра паразитов. [114] При повреждении, например, гусеницами чешуекрылых , листья растений, включая кукурузу и хлопок, выделяют повышенное количество летучих химических веществ, таких как терпены , которые сигнализируют о том, что они подвергаются нападению; одним из эффектов этого является привлечение паразитоидных ос, которые, в свою очередь, нападают на гусениц. [115]

Parasitism and parasite evolution were until the twenty-first century studied by parasitologists, in a science dominated by medicine, rather than by ecologists or evolutionary biologists. Even though parasite-host interactions were plainly ecological and important in evolution, the history of parasitology caused what the evolutionary ecologist Robert Poulin called a "takeover of parasitism by parasitologists", leading ecologists to ignore the area. This was in his opinion "unfortunate", as parasites are "omnipresent agents of natural selection" and significant forces in evolution and ecology.[116] In his view, the long-standing split between the sciences limited the exchange of ideas, with separate conferences and separate journals. The technical languages of ecology and parasitology sometimes involved different meanings for the same words. There were philosophical differences, too: Poulin notes that, influenced by medicine, "many parasitologists accepted that evolution led to a decrease in parasite virulence, whereas modern evolutionary theory would have predicted a greater range of outcomes".[116]

Their complex relationships make parasites difficult to place in food webs: a trematode with multiple hosts for its various life cycle stages would occupy many positions in a food web simultaneously, and would set up loops of energy flow, confusing the analysis. Further, since nearly every animal has (multiple) parasites, parasites would occupy the top levels of every food web.[84]

Parasites can play a role in the proliferation of non-native species. For example, invasive green crabs are minimally affected by native trematodes on the Eastern Atlantic coast. This helps them outcompete native crabs such as the Atlantic Rock and Jonah crabs.[117]

Ecological parasitology can be important to attempts at control, like during the campaign for eradicating the Guinea worm. Even though the parasite was eradicated in all but four countries, the worm began using frogs as an intermediary host before infecting dogs, making control more difficult than it would have been if the relationships had been better understood.[118]

Although parasites are widely considered to be harmful, the eradication of all parasites would not be beneficial. Parasites account for at least half of life's diversity; they perform important ecological roles; and without parasites, organisms might tend to asexual reproduction, diminishing the diversity of traits brought about by sexual reproduction.[119] Parasites provide an opportunity for the transfer of genetic material between species, facilitating evolutionary change.[120] Many parasites require multiple hosts of different species to complete their life cycles and rely on predator-prey or other stable ecological interactions to get from one host to another. The presence of parasites thus indicates that an ecosystem is healthy.[121]

An ectoparasite, the California condor louse, Colpocephalum californici, became a well-known conservation issue. A major and very costly captive breeding program was run in the United States to rescue the California condor. It was host to a louse, which lived only on it. Any lice found were "deliberately killed" during the program, to keep the condors in the best possible health. The result was that one species, the condor, was saved and returned to the wild, while another species, the parasite, became extinct.[122]

Although parasites are often omitted in depictions of food webs, they usually occupy the top position. Parasites can function like keystone species, reducing the dominance of superior competitors and allowing competing species to co-exist.[84][123][124]

A single parasite species usually has an aggregated distribution across host animals, which means that most hosts carry few parasites, while a few hosts carry the vast majority of parasite individuals. This poses considerable problems for students of parasite ecology, as it renders parametric statistics as commonly used by biologists invalid. Log-transformation of data before the application of parametric test, or the use of non-parametric statistics is recommended by several authors, but this can give rise to further problems, so quantitative parasitology is based on more advanced biostatistical methods.[125]

Human parasites including roundworms, the Guinea worm, threadworms and tapeworms are mentioned in Egyptian papyrus records from 3000 BC onwards; the Ebers Papyrus describes hookworm. In ancient Greece, parasites including the bladder worm are described in the Hippocratic Corpus, while the comic playwright Aristophanes called tapeworms "hailstones". The Roman physicians Celsus and Galen documented the roundworms Ascaris lumbricoides and Enterobius vermicularis.[126]

In his Canon of Medicine, completed in 1025, the Persian physician Avicenna recorded human and animal parasites including roundworms, threadworms, the Guinea worm and tapeworms.[126]

In his 1397 book Traité de l'état, science et pratique de l'art de la Bergerie (Account of the state, science and practice of the art of shepherding), Jehan de Brie wrote the first description of a trematode endoparasite, the sheep liver fluke Fasciola hepatica.[127][128]

In the early modern period, Francesco Redi's 1668 book Esperienze Intorno alla Generazione degl'Insetti (Experiences of the Generation of Insects), explicitly described ecto- and endoparasites, illustrating ticks, the larvae of nasal flies of deer, and sheep liver fluke.[129] Redi noted that parasites develop from eggs, contradicting the theory of spontaneous generation.[130] In his 1684 book Osservazioni intorno agli animali viventi che si trovano negli animali viventi (Observations on Living Animals found in Living Animals), Redi described and illustrated over 100 parasites including the large roundworm in humans that causes ascariasis.[129] Redi was the first to name the cysts of Echinococcus granulosus seen in dogs and sheep as parasitic; a century later, in 1760, Peter Simon Pallas correctly suggested that these were the larvae of tapeworms.[126]

In 1681, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek observed and illustrated the protozoan parasite Giardia lamblia, and linked it to "his own loose stools". This was the first protozoan parasite of humans to be seen under a microscope.[126] A few years later, in 1687, the Italian biologists Giovanni Cosimo Bonomo and Diacinto Cestoni described scabies as caused by the parasitic mite Sarcoptes scabiei, marking it as the first disease of humans with a known microscopic causative agent.[131]

Modern parasitology developed in the 19th century with accurate observations and experiments by many researchers and clinicians;[127] the term was first used in 1870.[132] In 1828, James Annersley described amoebiasis, protozoal infections of the intestines and the liver, though the pathogen, Entamoeba histolytica, was not discovered until 1873 by Friedrich Lösch. James Paget discovered the intestinal nematode Trichinella spiralis in humans in 1835. James McConnell described the human liver fluke, Clonorchis sinensis, in 1875.[126] Algernon Thomas and Rudolf Leuckart independently made the first discovery of the life cycle of a trematode, the sheep liver fluke, by experiment in 1881–1883.[127] In 1877 Patrick Manson discovered the life cycle of the filarial worms that cause elephantiasis transmitted by mosquitoes. Manson further predicted that the malaria parasite, Plasmodium, had a mosquito vector, and persuaded Ronald Ross to investigate. Ross confirmed that the prediction was correct in 1897–1898. At the same time, Giovanni Battista Grassi and others described the malaria parasite's life cycle stages in Anopheles mosquitoes. Ross was controversially awarded the 1902 Nobel prize for his work, while Grassi was not.[126] In 1903, David Bruce identified the protozoan parasite and the tsetse fly vector of African trypanosomiasis.[133]

Given the importance of malaria, with some 220 million people infected annually, many attempts have been made to interrupt its transmission. Various methods of malaria prophylaxis have been tried including the use of antimalarial drugs to kill off the parasites in the blood, the eradication of its mosquito vectors with organochlorine and other insecticides, and the development of a malaria vaccine. All of these have proven problematic, with drug resistance, insecticide resistance among mosquitoes, and repeated failure of vaccines as the parasite mutates.[134] The first and as of 2015 the only licensed vaccine for any parasitic disease of humans is RTS,S for Plasmodium falciparum malaria.[135]

Several groups of parasites, including microbial pathogens and parasitoidal wasps have been used as biological control agents in agriculture and horticulture.[137][138]

Poulin observes that the widespread prophylactic use of anthelmintic drugs in domestic sheep and cattle constitutes a worldwide uncontrolled experiment in the life-history evolution of their parasites. The outcomes depend on whether the drugs decrease the chance of a helminth larva reaching adulthood. If so, natural selection can be expected to favour the production of eggs at an earlier age. If on the other hand the drugs mainly affects adult parasitic worms, selection could cause delayed maturity and increased virulence. Such changes appear to be underway: the nematode Teladorsagia circumcincta is changing its adult size and reproductive rate in response to drugs.[139]

In the classical era, the concept of the parasite was not strictly pejorative: the parasitus was an accepted role in Roman society, in which a person could live off the hospitality of others, in return for "flattery, simple services, and a willingness to endure humiliation".[140][141]

Parasitism has a derogatory sense in popular usage. According to the immunologist John Playfair,[142]

In everyday speech, the term 'parasite' is loaded with derogatory meaning. A parasite is a sponger, a lazy profiteer, a drain on society.[142]

The satirical cleric Jonathan Swift alludes to hyperparasitism in his 1733 poem "On Poetry: A Rhapsody", comparing poets to "vermin" who "teaze and pinch their foes":[143]

The vermin only teaze and pinch

Their foes superior by an inch.

So nat'ralists observe, a flea

Hath smaller fleas that on him prey;

And these have smaller fleas to bite 'em.

And so proceeds ad infinitum.

Thus every poet, in his kind,

Is bit by him that comes behind:

A 2022 study examined the naming of some 3000 parasite species discovered in the previous two decades. Of those named after scientists, over 80% were named for men, whereas about a third of authors of papers on parasites were women. The study found that the percentage of parasite species named for relatives or friends of the author has risen sharply in the same period.[144]

In Bram Stoker's 1897 Gothic horror novel Dracula, and its many film adaptations, the eponymous Count Dracula is a blood-drinking parasite (a vampire). The critic Laura Otis argues that as a "thief, seducer, creator, and mimic, Dracula is the ultimate parasite. The whole point of vampirism is sucking other people's blood—living at other people's expense."[145]

Disgusting and terrifying parasitic alien species are widespread in science fiction,[146][147] as for instance in Ridley Scott's 1979 film Alien.[148][149] In one scene, a Xenomorph bursts out of the chest of a dead man, with blood squirting out under high pressure assisted by explosive squibs. Animal organs were used to reinforce the shock effect. The scene was filmed in a single take, and the startled reaction of the actors was genuine.[4][150]

Паразиты, если говорить кратко, это хищники, которые едят добычу группами менее одного экземпляра. Терпимые паразиты — это те, которые эволюционировали, чтобы обеспечить собственное выживание и воспроизводство, но в то же время с минимальными страданиями и затратами для хозяина.

Паразитизм — это форма симбиоза, тесная связь между двумя разными видами. Между хозяином и паразитом существует биохимическое взаимодействие; то есть они узнают друг друга, в конечном счете на молекулярном уровне, и ткани хозяина стимулируются к определенной реакции. Это объясняет, почему паразитизм может привести к болезни, но не всегда.

Predation, herbivory, and parasitism exist along a continuum of severity in terms of the extent to which they negatively affect an organism's fitness. ... In most situations, parasites do not kill their hosts. An exception, however, occurs with parasitoids, which blur the line between parasitism and predation.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка )XIX век можно считать временем зарождения современной паразитологии.

, стремящийся изобразить страдания клиента, естественно, сосредотачивается на отношениях с наибольшей зависимостью, в которых клиент получает пищу от своего покровителя, и для этого заранее сконструированная персона паразита оказалась чрезвычайно полезной.