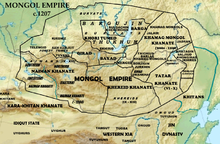

Монгольская империя XIII и XIV веков была крупнейшей смежной империей в истории . [5] Возникнув на территории современной Монголии в Восточной Азии , Монгольская империя на пике своего развития простиралась от Японского моря до частей Восточной Европы , распространяясь на север в части Арктики ; [6] на восток и юг в части Индийского субконтинента , организовывала вторжения в Юго-Восточную Азию и завоевала Иранское нагорье ; и достигала на западе Леванта и Карпатских гор .

Монгольская империя возникла из объединения нескольких кочевых племен в сердце Монголии под руководством Темучина, известного под более известным титулом Чингисхана ( ок . 1162 – 1227), которого совет провозгласил правителем всех монголов в 1206 году. Империя быстро росла под его правлением и правлением его потомков, которые отправляли вторгающиеся армии во всех направлениях. Огромная трансконтинентальная империя соединяла Восток с Западом , а Тихий океан со Средиземноморьем , в принудительном Pax Mongolica , позволяя обмениваться торговлей, технологиями, товарами и идеологиями по всей Евразии .

Империя начала распадаться из-за войн за престолонаследие, поскольку внуки Чингисхана спорили, должна ли королевская линия продолжаться от его сына и первоначального наследника Угедея или от одного из его других сыновей, таких как Толуй , Чагатай или Джучи . Толуиды одержали верх после кровавой чистки фракций Угедейдов и Чагатаидов, но споры продолжались среди потомков Толуя. Конфликт по поводу того, примет ли Монгольская империя оседлый, космополитический образ жизни или будет придерживаться своего кочевого, степного образа жизни, стал основным фактором распада.

После смерти Мункэ-хана (1259) соперничающие курултайские советы одновременно избрали разных преемников, братьев Ариг-Бугу и Хубилай-хана , которые сражались друг с другом в гражданской войне Толуидов (1260–1264), а также имели дело с вызовами со стороны потомков других сыновей Чингисхана. [7] [8] Хубилай успешно взял власть, но последовала война, поскольку он безуспешно пытался восстановить контроль над семьями Чагатаидов и Угедейдов . К моменту смерти Хубилая в 1294 году Монгольская империя распалась на четыре отдельных ханства или империи , каждая из которых преследовала свои собственные интересы и цели: Золотая Орда на северо-западе, Чагатайское ханство в Центральной Азии, Ильханат в Иране и династия Юань [примечание 1] в Китае, базирующаяся в современном Пекине . [13] В 1304 году, во время правления Темура , три западных ханства приняли сюзеренитет династии Юань. [14] [15]

Частью империи, которая пала первой, был Ильханат, который распался в период 1335–1353 годов. Затем династия Юань потеряла контроль над Тибетским нагорьем и собственно Китаем в 1354 и 1368 годах соответственно и рухнула после того, как ее столица Даду была захвачена войсками Мин . Затем правители Чингизидов из Юань отступили на север и продолжили править Монгольским нагорьем . После этого режим в историографии известен как династия Северная Юань , сохранившаяся как государство-осколок до завоевания династией Цин в 1630-х годах. К концу XV века Золотая Орда распалась на соперничающие ханства, и ее господство в Восточной Европе традиционно считается оконченным в 1480 году Великим Стоянием на реке Угре Великого княжества Московского , в то время как Чагатайское ханство просуществовало в той или иной форме до 1687 года.

В некоторых английских источниках Монгольская империя также упоминается как «Монгольская империя» или «Монгольская мировая империя». [16] [17] Империя называла себяᠶᠡᠬᠡ

ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ

ᠤᠯᠤᠰ yeke Mongγol ulus ( букв. «нация великих монголов» или «великая монгольская нация») на монгольском языке или kür uluγ ulus ( букв. «вся великая нация») на тюркском языке. [18]

После войны за престолонаследие 1260-1264 годов между Хубилай-ханом и его братом Ариг-Бугой власть Хубилая стала ограничиваться восточной частью империи, сосредоточенной в Китае. Хубилай официально издал императорский указ 18 декабря 1271 года, чтобы дать империи династическое название в стиле Хань «Великий Юань» ( Дай Юань или Дай Он Улус ; китайский :大元; пиньинь : Да Юань ) и основать династию Юань . Некоторые источники дают полное монгольское название как Дай Он Ехэ Монгул Улус . [19]

Территория вокруг Монголии , Маньчжурии и части Северного Китая контролировались династией Ляо под руководством киданей с 10-го века. В 1125 году династия Цзинь , основанная чжурчжэнями, свергла династию Ляо и попыталась получить контроль над бывшей территорией Ляо в Монголии. В 1130-х годах правители династии Цзинь, известные как Золотые короли, успешно сопротивлялись конфедерации Хамаг Монгол , которой в то время правил Хабул-хан , прадед Чингисхана. [20]

Монгольское плато было занято в основном пятью мощными племенными конфедерациями ( ханлигами ): кераитами , хамаг монголами , найманами , мергидами и татарами . Императоры Цзинь, следуя политике « разделяй и властвуй» , поощряли споры между племенами, особенно между татарами и монголами, чтобы отвлечь кочевые племена от своих собственных сражений и, таким образом, отдалить их от Цзинь. Преемником Хабула стал Амбагай-хан , который был предан татарами, передан чжурчжэням и казнен. Монголы отомстили, совершив набег на границу, что привело к неудачной контратаке чжурчжэней в 1143 году. [20]

В 1147 году Цзинь несколько изменили свою политику, подписав мирный договор с монголами и отступив из десятков фортов. Затем монголы возобновили нападения на татар, чтобы отомстить за смерть своего покойного хана, открыв длительный период активных военных действий. Армии Цзинь и татар разгромили монголов в 1161 году. [20]

Во время подъема Монгольской империи в 13 веке, обычно холодные, засушливые степи Центральной Азии наслаждались самыми мягкими, влажными условиями за более чем тысячелетие. Считается, что это привело к быстрому увеличению числа боевых лошадей и другого скота, что значительно увеличило военную мощь монголов. [21]

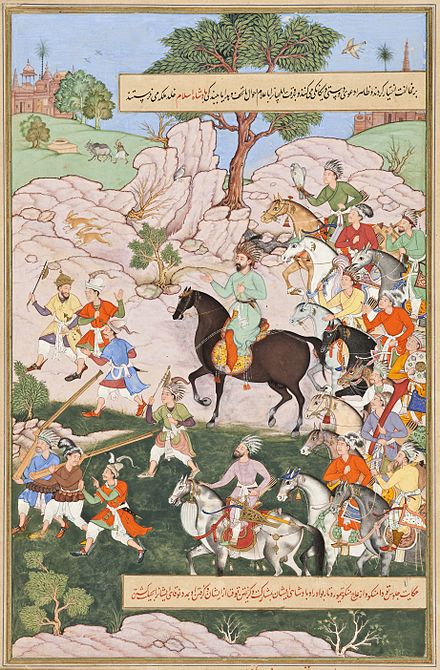

Известный в детстве как Темуджин, Чингисхан был сыном монгольского вождя и очень быстро возвысился в молодости, работая с Тогрул-ханом из кераитов. После того, как Темуджин пошел войной на Куртаита (также известного как Ван-хан; получив китайский титул «Ван» за его значение «король» [22] ), который был самым могущественным монгольским лидером в то время, он взял себе имя Чингисхан. Затем он расширил [ как? ] свое монгольское государство под своим началом и своими родственниками, и термин «монгол» стал использоваться по отношению ко всем монголоязычным племенам, находящимся под контролем Чингисхана. Его самыми могущественными союзниками были друг его отца, вождь кереитов Тогрул , и анда (т. е. кровный брат ) Темуджина в детстве Джамуха из клана Джадран. С их помощью Темучин разгромил племя меркитов, спас свою жену Бёрте и продолжил разгром найманов и татар. [23]

Темуджин запретил грабить своих врагов без разрешения, и он проводил политику дележа добычи со своими воинами и их семьями вместо того, чтобы отдавать ее всю аристократам. [24] Эта политика привела его к конфликту со своими дядями, которые также были законными наследниками престола; они считали Темуджина не лидером, а наглым узурпатором. Это недовольство распространилось на его генералов и других соратников, и некоторые монголы, которые ранее были союзниками, нарушили свою верность. [23] Последовала война, и Темуджин и силы, все еще верные ему, одержали победу, победив оставшиеся соперничающие племена между 1203 и 1205 годами и подчинив их своей власти. В 1206 году Темуджин был коронован как каган (император) Ехэ Монгол Улуса (Великого Монгольского государства) на курултае (генеральном собрании/совете). Именно там он принял титул Чингисхана (всеобщего лидера) вместо одного из старых племенных титулов, таких как Гур-хан или Таян-хан, что ознаменовало начало Монгольской империи. [23]

Чингисхан ввел много инновационных способов организации своей армии: например, разделив ее на десятичные подсекции арбанов (10 солдат), зуунов (100), мингханов (1000) и туменов (10 000). Была основана хешиг , императорская гвардия , которая делилась на дневную ( хорчин торгудс ) и ночную ( хевтуул ) гвардию. [25] Чингисхан вознаграждал тех, кто был ему верен, и ставил их на высокие должности, как глав армейских подразделений и домохозяйств, хотя многие из них происходили из очень низкоранговых кланов. [26]

По сравнению с подразделениями, которые он давал своим верным соратникам, тех, которые были назначены членам его собственной семьи, было относительно немного. Он провозгласил новый кодекс законов империи, Их Засаг или Ясса ; позже он расширил его, чтобы охватить большую часть повседневной жизни и политических дел кочевников. Он запретил продажу женщин, воровство, сражения между монголами и охоту на животных в период размножения. [26]

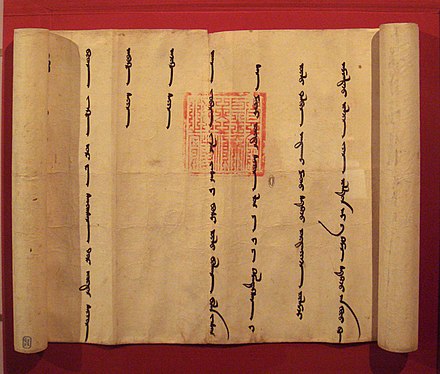

Он назначил своего сводного брата Шихи-Кхутуга верховным судьей (джаругачи), приказав ему вести записи империи. В дополнение к законам, касающимся семьи, продовольствия и армии, Чингисхан также установил религиозную свободу [ требуется ссылка ] и поддерживал внутреннюю и международную торговлю. Он освободил бедных и духовенство от налогов. [27] Он также поощрял грамотность и адаптацию уйгурской письменности в то, что стало монгольской письменностью империи, приказав уйгурскому Тата-тонга , который ранее служил хану найманов , обучать его сыновей. [28]

Чингисхан быстро вступил в конфликт с династией Цзинь чжурчжэней и Западной Ся тангутов в северном Китае. Ему также пришлось иметь дело с двумя другими державами, Тибетом и Кара-Китаем . [ 29]

Перед смертью Чингисхан разделил свою империю между сыновьями и ближайшими родственниками, сделав Монгольскую империю совместной собственностью всей императорской семьи, которая вместе с монгольской аристократией составляла правящий класс. [30]

Чингисхан организовал визит китайского даосского мастера Цю Чуцзи в Афганистан, а также предоставил своим подданным право на религиозную свободу, [ необходима цитата ] несмотря на его собственные шаманские верования.

Чингисхан умер 18 августа 1227 года, к тому времени Монгольская империя правила от Тихого океана до Каспийского моря , империя, вдвое превышающая по размерам Римскую империю или Мусульманский халифат в их расцвете. [ требуется ссылка ] Чингисхан назвал своего третьего сына, харизматичного Угедея , своим наследником. Согласно монгольской традиции, Чингисхан был похоронен в секретном месте . Регентство первоначально принадлежало младшему брату Угедея Толую до официального избрания Угедея на курултае в 1229 году. [31]

Среди первых действий Угедея были отправлены войска для покорения башкир , булгар и других народов в степях, контролируемых кипчаками. [32] На востоке армии Угедея восстановили монгольскую власть в Маньчжурии, сокрушив режим Восточного Ся и водяных татар . В 1230 году великий хан лично возглавил свою армию в походе против китайской династии Цзинь . Генерал Угедея Субутай захватил столицу императора Ваньянь Шоусюй во время осады Кайфэна в 1232 году. [33] Династия Цзинь рухнула в 1234 году, когда монголы захватили Цайчжоу , город, в который бежал Ваньянь Шоусюй. В 1234 году три армии под командованием сыновей Угедея Кочу и Котена и тангутского генерала Чагана вторглись в Южный Китай. При содействии династии Сун монголы покончили с Цзинь в 1234 году. [34] [35]

Многие ханьские китайцы и кидани перешли на сторону монголов, чтобы сражаться против Цзинь. Два лидера ханьских китайцев, Ши Тяньцзе , Лю Хэйма (劉黑馬, Лю Ни), [36] и киданьский Сяо Чжала перешли на сторону монголов и командовали тремя туменами в монгольской армии. [37] Лю Хэйма и Ши Тяньцзе служили Угэдэю-хану. [38] Лю Хэйма и Ши Тяньсян вели армии против Западной Ся для монголов. [39] Было четыре ханьских тумена и три киданьских тумена, каждый из которых состоял из 10 000 солдат. Династия Юань создала армию Хань 漢軍 из перебежчиков Цзинь, а другую — из бывших войск Сун, названную Новоподчиненной армией 新附軍. [40]

На Западе генерал Угедея Чормакан уничтожил Джалал ад-Дина Минбурну , последнего шаха Хорезмийской империи . Небольшие королевства на юге Персии добровольно приняли монгольское господство. [41] [42] В Восточной Азии было несколько монгольских походов в Корею Корё , но попытка Угедея аннексировать Корейский полуостров не увенчалась большим успехом. Кочжон , царь Корё , сдался, но позже восстал и убил монгольских даругачи (надзирателей); затем он переместил свой императорский двор из Кэсона на остров Канхвадо . [43]

В 1235 году монголы сделали Каракорум своей столицей, которая просуществовала до 1260 года. В этот период хан Угедей приказал построить дворец внутри его стен.

Между тем, в наступательных действиях против династии Сун , монгольские армии захватили Сиян-ян, Янцзы и Сычуань , но не обеспечили себе контроль над завоеванными территориями. Генералы Сун смогли отбить Сиян-ян у монголов в 1239 году. После внезапной смерти сына Угедея Кочу на китайской территории монголы отступили из Южного Китая, хотя брат Кочу принц Котен вторгся в Тибет сразу после их отступления. [23]

Батый-хан , другой внук Чингисхана, захватил территории булгар , аланов , кыпчаков, башкир, мордвы , чувашей и других народов южнорусских степей. К 1237 году монголы вторглись в Рязань , первое княжество Киевской Руси, на которое им предстояло напасть. После трехдневной осады, сопровождавшейся ожесточенными боями, монголы захватили город и вырезали его жителей. Затем они приступили к уничтожению армии Великого княжества Владимирского в битве на реке Сить . [44]

Монголы захватили столицу Алании Магас в 1238 году. К 1240 году вся Киевская Русь пала под натиском азиатских захватчиков, за исключением нескольких северных городов. Монгольские войска под командованием Чормака в Персии, связав свое вторжение в Закавказье с вторжением Батыя и Субудея, заставили грузинских и армянских дворян сдаться. [44]

Джованни де Плано Карпини , посланник папы римского к великому монгольскому хану, проезжал через Киев в феврале 1246 года и писал:

Они [монголы] напали на Русь, где произвели великое опустошение, разрушая города и крепости и убивая людей; и они осадили Киев, столицу Руси; после того, как они осаждали город в течение длительного времени, они взяли его и предали смерти жителей. Когда мы путешествовали по той земле, мы наткнулись на бесчисленные черепа и кости мертвых людей, лежащие на земле. Киев был очень большим и густонаселенным городом, но теперь он почти сведен к нулю, поскольку в настоящее время там едва ли осталось двести домов, а жители содержатся в полном рабстве. [45]

Несмотря на военные успехи, в рядах монголов продолжались раздоры. Отношения Бату с Гуюком , старшим сыном Угедея, и Бури , любимым внуком Чагатай-хана , оставались напряженными и ухудшились во время победного банкета Бату на юге Киевской Руси. Тем не менее, Гуюк и Бури не могли ничего сделать, чтобы навредить положению Бату, пока был жив его дядя Угедей. Угедей продолжал наступления на Индийский субконтинент , временно окружив Учч , Лахор и Мултан Делийского султаната и разместив монгольского надзирателя в Кашмире , [46] хотя вторжения в Индию в конечном итоге потерпели неудачу и были вынуждены отступить. В северо-восточной Азии Угедей согласился положить конец конфликту с Корё , сделав его клиентским государством и отправив монгольских принцесс замуж за принцев Корё. Затем он укрепил свои связи с корейцами как дипломатией, так и военной силой. [47] [48] [49]

Продвижение в Европу продолжилось монгольскими вторжениями в Польшу и Венгрию. Когда западный фланг монголов разграбил польские города, европейский союз поляков , моравов и христианских военных орденов госпитальеров , тевтонских рыцарей и тамплиеров собрал достаточно сил, чтобы остановить, хотя и ненадолго, монгольское наступление в Легнице . Венгерская армия, их хорватские союзники и тамплиеры были разбиты монголами на берегах реки Шажо 11 апреля 1241 года. Прежде чем войска Батыя смогли продолжить путь в Вену и северную Албанию , известие о смерти Угедея в декабре 1241 года остановило вторжение. [50] [51] Как было принято в монгольской военной традиции, все князья линии Чингисхана должны были присутствовать на курултае, чтобы выбрать преемника. Батый и его западно-монгольская армия покинули Центральную Европу в следующем году. [52] Сегодня исследователи сомневаются, что смерть Угедея была единственной причиной отступления монголов. Бату не вернулся в Монголию, поэтому новый хан не был избран до 1246 года. Климатические и экологические факторы, а также мощные укрепления и замки Европы сыграли важную роль в решении монголов отступить. [53] [54]

После смерти великого хана Угедея в 1241 году и перед следующим курултаем вдова Угедея Турегене захватила власть в империи. Она преследовала киданей и мусульманских чиновников своего мужа и давала высокие должности своим союзникам. Она строила дворцы, соборы и социальные структуры в имперском масштабе, поддерживая религию и образование. [55] Она смогла склонить на свою сторону большинство монгольских аристократов, чтобы поддержать сына Угедея Гуюка . Но Бату, правитель Золотой Орды , отказался приехать на курултай, заявив, что он болен и что климат слишком суров для него. Возникшая тупиковая ситуация длилась более четырех лет и еще больше дестабилизировала единство империи. [55]

Когда младший брат Чингисхана Темуге пригрозил захватить трон, Гуюк прибыл в Каракорум, чтобы попытаться укрепить свое положение. [56] В конце концов Бату согласился отправить своих братьев и генералов на курултай, созванный Турегене в 1246 году. К этому времени Гуюк был болен и страдал алкоголизмом, но его походы в Маньчжурию и Европу дали ему тот статус, который был необходим великому хану. Он был должным образом избран на церемонии, на которой присутствовали монголы и иностранные сановники как из империи, так и из-за ее пределов — лидеры вассальных государств, представители Рима и других образований, которые прибыли на курултай, чтобы проявить свое уважение и вести дипломатию. [57] [58]

Гуюк предпринял шаги по сокращению коррупции, объявив, что продолжит политику своего отца Угедея, а не Тёрегене. Он наказал сторонников Тёрегене, за исключением губернатора Аргуна Старшего . Он также заменил молодого Кара Хулегу , хана Чагатайского ханства , на своего любимого кузена Есу Мункэ , чтобы утвердить свои недавно дарованные полномочия. [59] Он восстановил чиновников своего отца на их прежних должностях и был окружен уйгурскими, найманскими и среднеазиатскими чиновниками, отдавая предпочтение китайским командирам хань , которые помогли его отцу завоевать Северный Китай. Он продолжил военные действия в Корее, продвинулся в Китай Сун на юге и в Ирак на западе и приказал провести перепись по всей империи. Гуюк также разделил Султанат Рум между Изз-ад-Дином Кайкавусом и Рукн ад-Дином Килидж Арсланом , хотя Кайкавус не согласился с этим решением. [59]

Не все части империи уважали выбор Гуюка. Хашшашины , бывшие монгольские союзники, чей великий магистр Хасан Джалалуд-Дин предложил свою покорность Чингисхану в 1221 году, разозлили Гуюка, отказавшись подчиниться. Вместо этого он убил монгольских генералов в Персии. Гуюк назначил отца своего лучшего друга Элджигидея главнокомандующим войсками в Персии и дал им задание как уменьшить опорные пункты низаритских исмаилитов , так и завоевать Аббасидов в центре исламского мира, Иране и Ираке . [59] [60]

В 1248 году Гуюк собрал больше войск и внезапно двинулся на запад из монгольской столицы Каракорума. Причины были неясны. Некоторые источники писали, что он пытался восстановить силы в своем личном поместье Эмиль; другие предполагали, что он мог двигаться, чтобы присоединиться к Элджигидею, чтобы провести полномасштабное завоевание Ближнего Востока, или, возможно, чтобы совершить внезапное нападение на своего соперника-двоюродного брата Бату-хана на Руси. [61]

Подозревая мотивы Гуюка, Соргахтани Беки , вдова сына Чингисхана Толуя, тайно предупредила своего племянника Бату о приближении Гуюка. Сам Бату в то время путешествовал на восток, возможно, чтобы выразить почтение, а может быть, и с другими планами. До того, как войска Бату и Гуюка встретились, Гуюк, больной и изнуренный путешествием, умер по дороге в Кум-Сенггире (Хун-сян-йи-эль) в Синьцзяне , возможно, став жертвой яда. [61]

Вдова Гуюка Огул Каймыш выступила вперед, чтобы взять под контроль империю, но ей не хватало навыков ее свекрови Турегене, а ее молодые сыновья Ходжа и Наку и другие принцы бросили вызов ее власти. Чтобы решить вопрос о новом великом хане, Бату созвал курултай на своей собственной территории в 1250 году. Поскольку это было далеко от монгольского сердца , члены семей Угедейдов и Чагатаидов отказались присутствовать. Курултай предложил трон Бату, но он отклонил его, заявив, что не заинтересован в этой должности. [62] Вместо этого Бату выдвинул кандидатуру Мункэ , внука Чингисхана из рода его сына Толуя. Мункэ возглавлял монгольскую армию на Руси, Северном Кавказе и в Венгрии. Протолуйская фракция поддержала выбор Бату, и Мункэ был избран; хотя, учитывая ограниченное количество участников курултая и его место проведения, его законность была сомнительной. [62]

Бату послал Мункэ под защитой его братьев Берке и Тохтемура и его сына Сартака собрать более формальный курултай в Кодое Арал в самом сердце страны. Сторонники Мункэ неоднократно приглашали Огула Каймыша и других крупных принцев Угедейдов и Чагатаидов посетить курултай, но они каждый раз отказывались. Угедейды и Чагатаиды отказались принять потомка сына Чингиса Толуя в качестве лидера, требуя, чтобы только потомки сына Чингиса Угедея могли стать великими ханами. [62]

Когда мать Мункэ Соргахтани и их двоюродный брат Берке организовали второй курултай 1 июля 1251 года, собравшаяся толпа провозгласила Мункэ великим ханом Монгольской империи. Это ознаменовало собой крупный сдвиг в руководстве империей, передав власть от потомков сына Чингиса Угедея потомкам сына Чингиса Толуя. Это решение было признано несколькими принцами Угедейдов и Чагатаидов, такими как двоюродный брат Мункэ Кадан и свергнутый хан Кара Хулегу, но один из других законных наследников, внук Угедея Ширемун, стремился свергнуть Мункэ. [63]

Ширемун двинулся со своими силами к императорскому дворцу кочевников с планом вооруженного нападения, но Мункэ был предупрежден своим сокольничим о плане. Мункэ приказал расследовать заговор, что привело к серии крупных судебных процессов по всей империи. Многие члены монгольской элиты были признаны виновными и казнены, по оценкам, от 77 до 300 человек, хотя принцы королевской линии Чингисхана часто были изгнаны, а не казнены. [63]

Мункэ конфисковал имения семей Угедейдов и Чагатаев и разделил западную часть империи со своим союзником Бату-ханом. После кровавой чистки Мункэ приказал провести всеобщую амнистию для пленных и пленников, но с тех пор власть на престоле великого хана прочно осталась за потомками Толуя. [63]

Мункэ был серьезным человеком, который следовал законам своих предков и избегал алкоголизма. Он был терпим к внешним религиям и художественным стилям, что привело к строительству кварталов иностранных купцов, буддийских монастырей , мечетей и христианских церквей в монгольской столице. По мере продолжения строительных проектов Каракорум был украшен китайской, европейской и персидской архитектурой . Одним из известных примеров было большое серебряное дерево с искусно спроектированными трубами, которые разливали различные напитки. Дерево, увенчанное торжествующим ангелом, было изготовлено Гийомом Буше , парижским ювелиром. [64]

Хотя у него был сильный китайский контингент, Мункэ в значительной степени полагался на мусульманских и монгольских администраторов и начал серию экономических реформ, чтобы сделать государственные расходы более предсказуемыми. Его двор ограничил государственные расходы и запретил дворянам и войскам оскорблять гражданских лиц или издавать указы без разрешения. Он заменил систему взносов фиксированным подушным налогом, который собирался имперскими агентами и направлялся нуждающимся подразделениям. [65] Его двор также пытался облегчить налоговое бремя для простолюдинов, снизив налоговые ставки. Он также централизовал контроль за денежными делами и усилил охрану на почтовых станциях. Мункэ приказал провести общеимперскую перепись в 1252 году, которая заняла несколько лет и была завершена только в 1258 году, когда был подсчитан Новгород на крайнем северо-западе. [65]

В другом шаге по консолидации своей власти Мункэ назначил своих братьев Хулагу и Хубилая править Персией и Китаем, находящимся под властью монголов, соответственно. В южной части империи он продолжил борьбу своих предшественников против династии Сун. Чтобы обойти Сун с трех сторон, Мункэ отправил монгольские армии под командованием своего брата Хубилая в Юньнань , а под командованием своего дяди Иеку — подчинить Корею и оказать давление на Сун также и с этого направления. [59]

Хубилай завоевал королевство Дали в 1253 году после того, как король Дали Дуань Синчжи перешел на сторону монголов и помог им завоевать остальную часть Юньнани . Генерал Мункэ Коридай стабилизировал свой контроль над Тибетом, убедив ведущие монастыри подчиниться монгольскому правлению. Сын Субутая Урянхадай заставил соседние народы Юньнани подчиниться и в 1258 году начал войну с королевством Дайвьет под династией Чан в северном Вьетнаме, но им пришлось отступить. [59] Монгольская империя снова попыталась вторгнуться в Дайвьет в 1285 и 1287 годах, но оба раза потерпела поражение.

.jpg/440px-Fall_Of_Baghdad_(Diez_Albums).jpg)

После стабилизации финансов империи Мункэ снова попытался расширить ее границы. На курултаях в Каракоруме в 1253 и 1258 годах он одобрил новые вторжения на Ближний Восток и в Южный Китай . Мункэ поставил Хулагу во главе военных и гражданских дел в Персии и назначил Чагатаидов и Джучидов присоединиться к армии Хулагу. [66]

Мусульмане из Казвина осудили угрозу низаритских исмаилитов , известной секты шиитов . Монгольский найманский командир Китбука начал штурмовать несколько исмаилитских крепостей в 1253 году, прежде чем Хулагу двинулся вперед в 1256 году. Исмаилитский великий магистр Рукн ад-Дин Хуршах сдался в 1257 году и был казнен. Все исмаилитские крепости в Персии были разрушены армией Хулагу в 1257 году, за исключением Гирдкуха , который продержался до 1271 года. [66]

Центром Исламской империи в то время был Багдад, который удерживал власть в течение 500 лет, но страдал от внутренних разногласий. Когда его халиф аль-Мустасим отказался подчиниться монголам, Багдад был осажден и захвачен монголами в 1258 году и подвергнут беспощадному разграблению, событие, которое считается одним из самых катастрофических событий в истории ислама, и иногда сравнивается с разрушением Каабы . С разрушением халифата Аббасидов Хулагу получил открытый путь в Сирию и двинулся против других мусульманских держав в регионе. [67]

Его армия двинулась к Сирии, управляемой Айюбидами , захватывая по пути небольшие местные государства. Султан Аль-Насир Юсуф из Айюбидов отказался показаться Хулагу; однако он принял монгольское господство два десятилетия назад. Когда Хулагу направился дальше на запад, армяне из Киликии , сельджуки из Рума и христианские королевства Антиохии и Триполи подчинились монгольской власти, присоединившись к ним в их нападении на мусульман. В то время как некоторые города сдались без сопротивления, другие, такие как Маяфаррикин, сопротивлялись; их население было вырезано, а города разграблены. [67]

Тем временем, в северо-западной части империи, преемник Бату и младший брат Берке отправил карательные экспедиции в Украину , Белоруссию , Литву и Польшу . Раздор начал назревать между северо-западной и юго-западной частями Монгольской империи, поскольку Бату подозревал, что вторжение Хулагу в Западную Азию приведет к устранению собственного господства Бату там. [68]

В южной части империи сам Мункэ-хан возглавил свою армию, но не завершил завоевание Китая. Военные операции в целом были успешными, но затянулись, поэтому войска не отступили на север, как это было принято, когда погода становилась жаркой. Болезни опустошали монгольские войска кровавыми эпидемиями, и Мункэ умер там 11 августа 1259 года. Это событие начало новую главу в истории монголов, поскольку снова нужно было принять решение о новом великом хане. Монгольские армии по всей империи вышли из своих походов, чтобы созвать новый курултай. [69]

Брат Мункэ Хулагу прервал свое успешное военное наступление в Сирии, отведя большую часть своих сил в Муган и оставив лишь небольшой контингент под командованием своего генерала Китбуки . Противоборствующие силы в регионе, христианские крестоносцы и мусульманские мамлюки, осознавая, что монголы представляют большую угрозу, воспользовались ослаблением монгольской армии и заключили необычное пассивное перемирие друг с другом. [70]

В 1260 году мамлюки выступили из Египта, получив разрешение разбить лагерь и пополнить запасы около христианской крепости Акра , и вступили в бой с войсками Китбуки к северу от Галилеи в битве при Айн-Джалуте . Монголы были разбиты, а Китбука казнен. Эта решающая битва ознаменовала западную границу монгольской экспансии на Ближнем Востоке, и монголы больше никогда не могли добиться серьезных военных успехов дальше Сирии. [70]

В отдельной части империи Хубилай-хан , другой брат Хулагу и Мункэ, услышал о смерти великого хана на реке Хуайхэ в Китае. Вместо того, чтобы вернуться в столицу, он продолжил свое продвижение в район Учан в Китае, недалеко от реки Янцзы . Их младший брат Арикбок воспользовался отсутствием Хулагу и Хубилая и использовал свое положение в столице, чтобы завоевать титул великого хана для себя, а представители всех семейных ветвей провозгласили его лидером на курултае в Каракоруме. Когда Хубилай узнал об этом, он созвал свой собственный курултай в Кайпине , и почти все старшие принцы и великие нойоны в Северном Китае и Маньчжурии поддержали его собственную кандидатуру вместо кандидатуры Арикбокэ. [52]

Сражения последовали между армиями Хубилая и его брата Арикбоке, в состав которых входили силы, все еще лояльные предыдущей администрации Мункэ. Армия Хубилая легко уничтожила сторонников Арикбоке и захватила контроль над гражданской администрацией в южной Монголии. Дальнейшие проблемы возникли со стороны их кузенов, Чагатаидов. [71] [72] [73] Хубилай послал Абишку, лояльного ему чагатаидского принца, взять на себя управление царством Чагатая. Но Арикбоке захватил и затем казнил Абишку, вместо этого короновав там своего человека Алгу . Новая администрация Хубилая блокировала Арикбоке в Монголии, чтобы отрезать поставки продовольствия, что вызвало голод. Каракорум быстро пал перед Хубилаем, но Арикбоке сплотился и отвоевал столицу в 1261 году. [71] [72] [73]

На юго-западе Ильханата Хулагу был верен своему брату Хубилаю, но в 1262 году начались столкновения с их двоюродным братом Берке, мусульманином и правителем Золотой Орды. Подозрительные смерти джучидских принцев на службе у Хулагу, неравное распределение военной добычи и резня мусульман Хулагу усилили гнев Берке, который рассматривал возможность поддержки восстания Грузинского царства против правления Хулагу в 1259–1260 годах. [74] [ необходима полная цитата ] Берке также заключил союз с египетскими мамлюками против Хулагу и поддержал соперника Хубилая, претендента Аригбоку. [75]

Хулагу умер 8 февраля 1264 года. Берке пытался воспользоваться этим и вторгнуться во владения Хулагу, но он умер по пути, а несколько месяцев спустя Алгу-хан Чагатайского ханства также умер. Хубилай назначил сына Хулагу Абаку новым ильханом и назначил внука Бату Мёнке-Тэмура главой Золотой Орды. Абака искал иностранных союзов, таких как попытка сформировать франко-монгольский союз против египетских мамлюков. [76] Арикбоке сдался Хубилаю в Шанду 21 августа 1264 года. [77]

На юге, после падения Сянъяна в 1273 году, монголы стремились к окончательному завоеванию династии Сун в Южном Китае. В 1271 году Хубилай переименовал новый монгольский режим в Китае в династию Юань и стремился китаизировать свой образ императора Китая , чтобы завоевать контроль над китайским народом. Хубилай перенес свою ставку в Ханбалык, место зарождения того, что позже стало современным городом Пекин . Его создание там столицы было спорным шагом для многих монголов, которые обвиняли его в слишком тесной связи с китайской культурой . [78] [79]

The Mongols were eventually successful in their campaigns against (Song) China, and the Chinese Song imperial family surrendered to the Yuan in 1276, making the Mongols the first non-Chinese people to conquer all of China. Kublai used his base to build a powerful empire, creating an academy, offices, trade ports and canals, and sponsoring arts and science. Mongol records list 20,166 public schools created during his reign.[80]

After achieving actual or nominal dominion over much of Eurasia and successfully conquering China, Kublai pursued further expansion. His invasions of Burma and Sakhalin were costly, and his attempted invasions of Đại Việt (northern Vietnam) and Champa (southern Vietnam) ended in devastating defeat, but secured vassal statuses of those countries. The Mongol armies were repeatedly beaten in Đại Việt and were crushed at the Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288).

Nogai and Konchi, the khan of the White Horde, established friendly relations with the Yuan dynasty and the Ilkhanate. Political disagreement among contending branches of the family over the office of great khan continued, but the economic and commercial success of the Mongol Empire continued despite the squabbling.[81][82][83]

In 1274 and again in 1281, Kublai Khan invaded Japan on two separate occasions. However, he was not able to conquer Japan. In the period of the Mongol invasion, the battles of Bun'ei and Kōan were fought along the coast of Hakata Bay near modern-day Fukuoka.

Major changes occurred in the Mongol Empire in the late 1200s. Kublai Khan, after having conquered all of China and established the Yuan dynasty, died in 1294. He was succeeded by his grandson Temür Khan, who continued Kublai's policies. At the same time the Toluid Civil War, along with the Berke–Hulagu war and the subsequent Kaidu–Kublai war, greatly weakened the authority of the great khan over the entirety of the Mongol Empire and the empire fractured into autonomous khanates, the Yuan dynasty and the three western khanates: the Golden Horde, the Chagatai Khanate and the Ilkhanate. Only the Ilkhanate remained loyal to the Yuan court but endured its own power struggle, in part because of a dispute with the growing Islamic factions within the southwestern part of the empire.[84]

After the death of Kaidu, the Chatagai ruler Duwa initiated a peace proposal and persuaded the Ögedeids to submit to Temür Khan.[85][86] In 1304, all of the khanates approved a peace treaty and accepted Yuan emperor Temür's supremacy.[87][88][89][90] This established the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty over the western khanates, which was to last for several decades. This supremacy was based on weaker foundations than that of the earlier Khagans and each of the four khanates continued to develop separately and function as independent states.

Nearly a century of conquest and civil war was followed by relative stability, the Pax Mongolica, and international trade and cultural exchanges flourished between Asia and Europe. Communication between the Yuan dynasty in China and the Ilkhanate in Persia further encouraged trade and commerce between east and west. Patterns of Yuan royal textiles could be found on the opposite side of the empire adorning Armenian decorations; trees and vegetables were transplanted across the empire; and technological innovations spread from Mongol dominions toward the West.[91] Pope John XXII was presented a memorandum from the eastern church describing the Pax Mongolica: "... Khagan is one of the greatest monarchs and all lords of the state, e.g., the king of Almaligh (Chagatai Khanate), emperor Abu Said and Uzbek Khan, are his subjects, saluting his holiness to pay their respects."[92] However, while the four khanates continued to interact with one another well into the 14th century, they did so as sovereign states and never again pooled their resources in a cooperative military endeavor.[93]

In spite of his conflicts with Kaidu and Duwa, Yuan emperor Temür established a tributary relationship with the war-like Shan people after his series of military operations against Thailand from 1297 to 1303. This was to mark the end of the southern expansion of the Mongols.

When Ghazan took the throne of the Ilkhanate in 1295, he formally accepted Islam as his own religion, marking a turning point in Mongol history after which Mongol Persia became more and more Islamic. Despite this, Ghazan continued to strengthen ties with Temür Khan and the Yuan dynasty in the east. It was politically useful to advertise the great khan's authority in the Ilkhanate, because the Golden Horde in Rus had long made claims on nearby Georgia.[84] Within four years, Ghazan began sending tribute to the Yuan court and appealing to other khans to accept Temür Khan as their overlord. He oversaw an extensive program of cultural and scientific interaction between the Ilkhanate and the Yuan dynasty in the following decades.[95]

Ghazan's faith may have been Islamic, but he continued his ancestors' war with the Egyptian Mamluks, and consulted with his old Mongol advisers in his native tongue. He defeated the Mamluk army at the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in 1299, but he was only briefly able to occupy Syria, due to distracting raids from the Chagatai Khanate under its de facto ruler Kaidu, who was at war with both the Ilkhans and the Yuan dynasty.[citation needed]

Struggling for influence within the Golden Horde, Kaidu sponsored his own candidate Kobeleg against Bayan (r. 1299–1304), the khan of the White Horde. Bayan, after receiving military support from the Mongols in Rus, requested assistance from both Temür Khan and the Ilkhanate to organize a unified attack against Kaidu's forces. Temür was amenable and attacked Kaidu a year later. After a bloody battle with Temür's armies near the Zawkhan River in 1301, Kaidu died and was succeeded by Duwa.[96][97]

Duwa was challenged by Kaidu's son Chapar, but with the assistance of Temür, Duwa defeated the Ögedeids. Tokhta of the Golden Horde, also seeking a general peace, sent 20,000 men to buttress the Yuan frontier.[98] Tokhta died in 1312, though, and was succeeded by Ozbeg (r. 1313–41), who seized the throne of the Golden Horde and persecuted non-Muslim Mongols. The Yuan's influence on the Horde was largely reversed and border clashes between Mongol states resumed. Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan's envoys backed Tokhta's son against Ozbeg.[citation needed]

In the Chagatai Khanate, Esen Buqa I (r. 1309–1318) was enthroned as khan after suppressing a sudden rebellion by Ögedei's descendants and driving Chapar into exile. The Yuan and Ilkhanid armies eventually attacked the Chagatai Khanate. Recognising the potential economic benefits and the Genghisid legacy, Ozbeg reopened friendly relations with the Yuan in 1326. He strengthened ties with the Muslim world as well, building mosques and other elaborate structures such as baths.[citation needed] By the second decade of the 14th century, Mongol invasions had further decreased. In 1323, Abu Said Khan (r. 1316–35) of the Ilkhanate signed a peace treaty with Egypt. At his request, the Yuan court awarded his custodian Chupan the title of commander-in-chief of all Mongol khanates, but Chupan died in late 1327.[99]

Civil war erupted in the Yuan dynasty in 1328–29. After the death of Yesün Temür in 1328, Tugh Temür became the new leader in Khanbaliq, while Yesün Temür's son Ragibagh succeeded to the throne in Shangdu, leading to the civil war known as the War of the Two Capitals. Tugh Temür defeated Ragibagh, but the Chagatai khan Eljigidey (r. 1326–29) supported Kusala, elder brother of Tugh Temür, as great khan. He invaded with a commanding force, and Tugh Temür abdicated. Kusala was elected khan on 30 August 1329. Kusala was then poisoned by a Kypchak commander under Tugh Temür, who returned to power.

Tugh Temür (1304–32) was knowledgeable about Chinese language and history and was also a creditable poet, calligrapher, and painter. In order to be accepted by other khanates as the sovereign of the Mongol world, he sent Genghisid princes and descendants of notable Mongol generals to the Chagatai Khanate, Ilkhan Abu Said, and Ozbeg. In response to the emissaries, they all agreed to send tribute each year.[100] Furthermore, Tugh Temür gave lavish presents and an imperial seal to Eljigidey to mollify his anger.

.jpg/440px-Iron_Helmet,_Mongol_Empire_(19219750434).jpg)

With the death of Ilkhan Abu Said Bahatur in 1335, Mongol rule faltered and Persia fell into political anarchy. A year later his successor was killed by an Oirat governor, and the Ilkhanate was divided between the Suldus, the Jalayir, Qasarid Togha Temür (d. 1353), and Persian warlords. Taking advantage of the chaos, the Georgians pushed the Mongols out of their territory, and the Uyghur commander Eretna established an independent state (Eretnids) in Anatolia in 1336. Following the downfall of their Mongol masters, the loyal vassal, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, received escalating threats from the Mamluks and were eventually overrun in 1375.[101]Along with the dissolution of the Ilkhanate in Persia, Mongol rulers in China and the Chagatai Khanate were also in turmoil. The plague known as the Black Death, which started in the Mongol dominions and spread to Europe, added to the confusion.[102] Disease devastated all the khanates, cutting off commercial ties and killing millions.[103] The plague may have taken 50 million lives in Europe alone in the 14th century.[104]

As the power of the Mongols declined, chaos erupted throughout the empire as non-Mongol leaders expanded their own influence. The Golden Horde lost all of its western dominions (including modern Belarus and Ukraine) to Poland and Lithuania between 1342 and 1369. Muslim and non-Muslim princes in the Chagatai Khanate warred with each other from 1331 to 1343, and the Chagatai Khanate disintegrated when non-Genghisid warlords set up their own puppet khans in Transoxiana and Moghulistan. Janibeg Khan (r. 1342–1357) briefly reasserted Jochid dominance over the Chaghataids. Demanding submission from an offshoot of the Ilkhanate in Azerbaijan, he boasted that "today three uluses are under my control".[105]

However, rival families of the Jochids began fighting for the throne of the Golden Horde (Great Troubles, 1359–1381) after the assassination of his successor Berdibek Khan in 1359. The last Yuan ruler Toghan Temür (r. 1333–70) was powerless to regulate those troubles, a sign that the empire had nearly reached its end. His court's unbacked currency had entered a hyperinflationary spiral and the Han-Chinese people revolted due to the Yuan's harsh impositions. In the 1350s, Gongmin of Goryeo successfully pushed Mongol garrisons back and exterminated the family of Toghan Temür Khan's empress while Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen managed to eliminate the Mongol influence in Tibet.[105]

Increasingly isolated from their subjects, the Mongols quickly lost most of China to the rebellious Ming forces and in 1368 fled to their heartland in Mongolia. After the overthrow of the Yuan dynasty the Golden Horde lost touch with Mongolia and China, while the two main parts of the Chagatai Khanate were defeated by Timur (Tamerlane) (1336–1405), who founded the Timurid Empire. However, remnants of the Chagatai Khanate survived; the last Chagataid state to survive was the Yarkent Khanate, until its defeat by the Oirat Dzungar Khanate in the Dzungar conquest of Altishahr in 1680. The Golden Horde broke into smaller Turkic-hordes that declined steadily in power over four centuries. Among them, the khanate's shadow, the Great Horde, survived until 1502, when one of its successors, the Crimean Khanate, sacked Sarai.[106] The Crimean Khanate lasted until 1783, whereas khanates such as the Khanate of Bukhara and the Kazakh Khanate lasted even longer.

.jpg/440px-Genghis_Khan_The_Exhibition_(5465078899).jpg)

The number of troops mustered by the Mongols is the subject of some scholarly debate,[107] but was at least 105,000 in 1206.[108] The Mongol military organization was simple but effective, based on the decimal system. The army was built up from squads of ten men each, arbans (10 people), zuuns (100), Mingghans (1000), and tumens (10,000).[109]

The Mongols were most famous for their horse archers, but troops armed with lances were equally skilled, and the Mongols recruited other military specialists from the lands they conquered. With experienced Chinese engineers and a bombardier corps which was expert at building trebuchets, catapults and other machines, the Mongols could lay siege to fortified positions, sometimes building machinery on the spot using available local resources.[109]

Forces under the command of the Mongol Empire were trained, organized, and equipped for mobility and speed. Mongol soldiers were more lightly armored than many of the armies they faced but were able to make up for it with maneuverability. Each Mongol warrior would usually travel with multiple horses, allowing him to quickly switch to a fresh mount as needed. In addition, soldiers of the Mongol army functioned independently of supply lines, considerably speeding up army movement.[110] Skillful use of couriers enabled the leaders of these armies to maintain contact with each other.

Discipline was inculcated during a nerge (traditional hunt), as reported by Juvayni. These hunts were distinctive from hunts in other cultures, being the equivalent to small unit actions. Mongol forces would spread out in a line, surround an entire region, and then drive all of the game within that area together. The goal was to let none of the animals escape and to slaughter them all.[110]

Another advantage of the Mongols was their ability to traverse large distances, even in unusually cold winters; for instance, frozen rivers led them like highways to large urban centers on their banks. The Mongols were adept at river-work, crossing the river Sajó in spring flood conditions with thirty thousand cavalry soldiers in a single night during the Battle of Mohi (April 1241) to defeat the Hungarian king Béla IV. Similarly, in the attack against the Muslim Khwarezmshah a flotilla of barges was used to prevent escape on the river.[citation needed]

Traditionally known for their prowess with ground forces, the Mongols rarely used naval power. In the 1260s and 1270s they used seapower while conquering the Song dynasty of China, though their attempts to mount seaborne campaigns against Japan were unsuccessful. Around the Eastern Mediterranean, their campaigns were almost exclusively land-based, with the seas controlled by the Crusader and Mamluk forces.[111]

All military campaigns were preceded by careful planning, reconnaissance, and the gathering of sensitive information relating to enemy territories and forces. The success, organization, and mobility of the Mongol armies permitted them to fight on several fronts at once. All adult males up to the age of 60 were eligible for conscription into the army, a source of honor in their tribal warrior tradition.[112]

The Mongol Empire was governed by a code of law devised by Genghis, called Yassa, meaning "order" or "decree". A particular canon of this code was that those of rank shared much the same hardship as the common man. It also imposed severe penalties, e.g., the death penalty if one mounted soldier following another did not pick up something dropped from the mount in front. Penalties were also decreed for rape and to some extent for murder. Any resistance to Mongol rule was met with massive collective punishment. Cities were destroyed and their inhabitants slaughtered if they defied Mongol orders.[citation needed] Under Yassa, chiefs and generals were selected based on merit. The empire was governed by a non-democratic, parliamentary-style central assembly, called kurultai, in which the Mongol chiefs met with the great khan to discuss domestic and foreign policies. Kurultais were also convened for the selection of each new great khan.[113]

The Mongols imported Central Asian Muslims to serve as administrators in China and sent Han Chinese and Khitans from China to serve as administrators over the Muslim population in Bukhara in Central Asia, thus using foreigners to curtail the power of the local peoples of both lands.[114]

At the time of Genghis Khan, virtually every religion had found Mongol converts, from Buddhism to Christianity, from Manichaeism to Islam. To avoid strife, Genghis Khan set up an institution that ensured complete religious freedom, though he himself was a shamanist. Under his administration, all religious leaders were exempt from taxation and from public service.[115]

Initially there were few formal places of worship because of the nomadic lifestyle. However, under Ögedei (1186–1241), several building projects were undertaken in the Mongol capital. Along with palaces, Ögedei built houses of worship for the Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, and Taoist followers. The dominant religions at that time were Tengrism and Buddhism, although Ögedei's wife was a Nestorian Christian.[116]

Eventually, each of the successor states adopted the dominant religion of the local populations: the Mongol-ruled Chinese Yuan dynasty in the East (originally the Great Khan's domain) embraced Buddhism and Shamanism, while the three Western khanates adopted Islam.[117][118][119]

The oldest surviving literary work in the Mongolian language is The Secret History of the Mongols, which was written for the royal family some time after Genghis Khan's death in 1227. It is the most significant native account of Genghis's life and genealogy, covering his origins and childhood through to the establishment of the Mongol Empire and the reign of his son, Ögedei.

Another classic from the empire is the Jami' al-tawarikh, or "Universal History". It was commissioned in the early 14th century by the Ilkhan Abaqa Khan as a way of documenting the entire world's history, to help establish the Mongols' own cultural legacy.

Mongol scribes in the 14th century used a mixture of resin and vegetable pigments as a primitive form of correction fluid;[120] this is arguably its first known usage.

The Mongols also appreciated the visual arts, though their taste in portraiture was strictly focused on portraits of their horses, rather than of people.[citation needed]

The Mongol Empire saw some significant developments in science due to the patronage of the Khans. Roger Bacon attributed the success of the Mongols as world conquerors principally to their devotion to mathematics.[121] Astronomy was one branch of science that the Khans took a personal interest in. According to the Yuanshi, Ögedei Khan twice ordered the armillary sphere of Zhongdu to be repaired (in 1233 and 1236) and also ordered in 1234 the revision and adoption of the Damingli calendar.[122] He built a Confucian temple for Yelü Chucai in Karakorum around 1236 where Yelü Chucai created and regulated a calendar on the Chinese model. Möngke Khan was noted by Rashid al-Din as having solved some of the difficult problems of Euclidean geometry on his own and written to his brother Hulagu Khan to send him the astronomer Tusi.[123] Möngke Khan's desire to have Tusi build him an observatory in Karakorum did not reach fruition as the Khan died on campaign in southern China. Hulagu Khan instead gave Tusi a grant to build the Maragheh Observatory in Persia in 1259 and ordered him to prepare astronomical tables for him in 12 years, despite Tusi asking for 30 years. Tusi successfully produced the Ilkhanic Tables in 12 years, produced a revised edition of Euclid's elements and taught the innovative mathematical device called the Tusi couple. The Maragheh observatory held around 400,000 books salvaged by Tusi from the siege of Baghdad and other cities. Chinese astronomers brought by Hulagu Khan worked there as well.

Kublai Khan built a number of large observatories in China and his libraries included the Wu-hu-lie-ti (Euclid) brought by Muslim mathematicians.[124] Zhu Shijie and Guo Shoujing were notable mathematicians in Yuan China. The Mongol physician Hu Sihui described the importance of a healthy diet in a 1330 medical treatise.

Ghazan Khan, able to understand four languages including Latin, built the Tabriz Observatory in 1295. The Byzantine Greek astronomer Gregory Chioniades studied there under Ajall Shams al-Din Omar who had worked at Maragheh under Tusi. Chioniades played an important role in transmitting several innovations from the Islamic world to Europe. These include the introduction of the universal latitude-independent astrolabe to Europe and a Greek description of the Tusi-couple, which would later have an influence on Copernican heliocentrism. Choniades also translated several Zij treatises into Greek, including the Persian Zij-i Ilkhani by al-Tusi and the Maragheh observatory. The Byzantine-Mongol alliance and the fact that the Empire of Trebizond was an Ilkhanate vassal facilitated Choniades' movements between Constantinople, Trebizond and Tabriz. Prince Radna, the Mongol viceroy of Tibet based in Gansu province, patronized the Samarkandi astronomer al-Sanjufini. The Arabic astronomical handbook dedicated by al-Sanjufini to Prince Radna, a descendant of Kublai Khan, was completed in 1363. It is notable for having Middle Mongolian glosses on its margins.[125]

The Mongol Empire had an ingenious and efficient mail system for the time, often referred to by scholars as the Yam. It had lavishly furnished and well-guarded relay posts known as örtöö set up throughout the Empire.[126] A messenger would typically travel 40 kilometres (25 miles) from one station to the next, either receiving a fresh, rested horse, or relaying the mail to the next rider to ensure the speediest possible delivery. The Mongol riders regularly covered 200 km (125 mi) per day, better than the fastest record set by the Pony Express some 600 years later.[citation needed] The relay stations had attached households to service them. Anyone with a paiza was allowed to stop there for re-mounts and specified rations, while those carrying military identities used the Yam even without a paiza. Many merchants, messengers, and travelers from China, the Middle East, and Europe used the system. When the great khan died in Karakorum, news reached the Mongol forces under Batu Khan in Central Europe within 4–6 weeks thanks to the Yam.[50]

Genghis and his successor Ögedei built a wide system of roads, one of which carved through the Altai mountains. After his enthronement, Ögedei further expanded the road system, ordering the Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde to link up roads in western parts of the Mongol Empire.[127]

Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan dynasty, built special relays for high officials, as well as ordinary relays, that had hostels. During Kublai's reign, the Yuan communication system consisted of some 1,400 postal stations, which used 50,000 horses, 8,400 oxen, 6,700 mules, 4,000 carts, and 6,000 boats.[citation needed]

In Manchuria and southern Siberia, the Mongols still used dogsled relays for the Yam. In the Ilkhanate, Ghazan restored the declining relay system in the Middle East on a restricted scale. He constructed some hostels and decreed that only imperial envoys could receive a stipend. The Jochids of the Golden Horde financed their relay system by a special Yam tax.[citation needed]

The Mongols had a history of supporting merchants and trade. Genghis Khan had encouraged foreign merchants early in his career, even before uniting the Mongols. Merchants provided information about neighboring cultures, served as diplomats and official traders for the Mongols, and were essential for many goods, since the Mongols produced little of their own.

Mongol government and elites provided capital for merchants and sent them far afield, in an ortoq (merchant partner) arrangement. In Mongol times, the contractual features of a Mongol-ortoq partnership closely resembled that of qirad and commenda arrangements, however, Mongol investors were not constrained using uncoined precious metals and tradable goods for partnership investments and primarily financed money-lending and trade activities.[128] Moreover, Mongol elites formed trade partnerships with merchants from Italian cities, including Marco Polo's family.[129] As the empire grew, any merchants or ambassadors with proper documentation and authorization received protection and sanctuary as they traveled through Mongol realms. Well-traveled and relatively well-maintained roads linked lands from the Mediterranean basin to China, greatly increasing overland trade and resulting in some dramatic stories of those who travelled through what would become known as the Silk Road.

Western explorer Marco Polo traveled east along the Silk Road, and the Chinese Mongol monk Rabban Bar Sauma made a comparably epic journey along the route, venturing from his home of Khanbaliq (Beijing) as far as Europe. European missionaries, such as William of Rubruck, also traveled to the Mongol court to convert believers to their cause, or went as papal envoys to correspond with Mongol rulers in an attempt to secure a Franco-Mongol alliance. It was rare, however, for anyone to journey the full length of Silk Road. Instead, merchants moved products like a bucket brigade, goods being traded from one middleman to another, moving from China all the way to the West; the goods moved over such long distances fetched extravagant prices.[citation needed]

_mint.jpg/440px-Gold_coin_of_Genghis_Khan,_struck_at_the_Ghazna_(Ghazni)_mint.jpg)

After Genghis, the merchant partner business continued to flourish under his successors Ögedei and Güyük. Merchants brought clothing, food, information, and other provisions to the imperial palaces, and in return the great khans gave the merchants tax exemptions and allowed them to use the official relay stations of the Mongol Empire. Merchants also served as tax farmers in China, Rus and Iran. If the merchants were attacked by bandits, losses were made up from the imperial treasury.[citation needed]

Policies changed under the Great Khan Möngke. Because of money laundering and overtaxing, he attempted to limit abuses and sent imperial investigators to supervise the ortoq businesses. He decreed that all merchants must pay commercial and property taxes, and he paid off all drafts drawn by high-ranking Mongol elites from the merchants. This policy continued under the Yuan dynasty.[citation needed]

The fall of the Mongol Empire in the 14th century led to the collapse of the political, cultural, and economic unity along the Silk Road. Turkic tribes seized the western end of the route from the Byzantine Empire, sowing the seeds of a Turkic culture that would later crystallize into the Ottoman Empire under the Sunni faith. In the East, the Han Chinese overthrew the Yuan dynasty in 1368, launching their own Ming dynasty and pursuing a policy of economic isolationism.[130]

The Mongol Empire, at its height of the largest contiguous empire in history, had a lasting impact, unifying large regions. Some of these (such as eastern and western Russia, and the western parts of China) remain unified today.[131] Mongols might have been assimilated into local populations after the fall of the empire, and some of their descendants adopted local religions. For example, the eastern khanate largely adopted Buddhism, and the three western khanates adopted Islam, largely under Sufi influence.[117]

According to some[specify] interpretations, Genghis Khan's conquests caused wholesale destruction on an unprecedented scale in certain geographic regions, leading to changes in the demographics of Asia.

The non-military achievements of the Mongol Empire include the introduction of a writing system, a Mongol alphabet based on the characters of the Old Uyghur, which is still used in Mongolia today.[132]

Some of the other long-term consequences of the Mongol Empire include:

[I]n this region [Mesopotamia] nomadism really did attempt, and really did to a very considerable degree succeed in its attempt, to stamp a settled civilized system out of existence. When Jengis Khan first invaded China, we are told that there was a serious discussion among the Mongol chiefs whether all the towns and settled populations should not be destroyed. To these simple practitioners of the open-air life the settled populations seemed corrupt, crowded, vicious, effeminate, dangerous, and incomprehensible; a detestable human efflorescence upon what would otherwise have been good pasture. They had no use whatever for the towns. **** But it was only under Hulagu in Mesopotamia that these ideas seem to have been embodied in a deliberate policy. The Mongols here did not only burn and massacre; they destroyed the irrigation system that had endured for at least eight thousand years, and with that the mother civilization of all the Western world came to an end.[137]

元年丙寅,帝大会诸王群臣,建九斿白旗,即皇帝位于斡难河之源,诸王群臣共上尊号曰成吉思皇帝。[In the first year of Bingyin [1206], the emperor gathered all the kings and ministers to build the Jiumai White Banner, that is, the emperor was located at the source of the Onan River, and all the kings and ministers honored him as Emperor Genghis.]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)