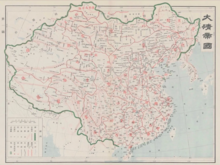

Династия Цин ( / tʃ ɪ ŋ / ching ), официально Великая Цин , [d] была маньчжурской императорской династией Китая и последней императорской династией в истории Китая . Династия, провозглашенная в Шэньяне в 1636 году, [7] захватила контроль над Пекином в 1644 году, что считается началом правления династии. [2] [1] [8] [9] [10] [11] Династия просуществовала до 1912 года, когда она была свергнута в ходе Синьхайской революции . В китайской историографии династию Цин предшествовала династия Мин , а ее преемницей стала Китайская Республика . Многоэтническая династия Цин собрала территориальную базу для современного Китая . Это была крупнейшая императорская династия в истории Китая и в 1790 году четвертая по величине империя в мировой истории с точки зрения территориального размера. С более чем 426 миллионами граждан в 1907 году [ 12] это была самая густонаселенная страна в мире в то время.

Нурхаци , лидер дома Айсин-Гиоро и вассал династии Мин, [13] [14] объединил кланы чжурчжэней (позже известные как маньчжуры) и основал династию Поздняя Цзинь в 1616 году, отказавшись от господства Мин. Его сын Хун Тайцзи был провозглашен императором Великой Цин в 1636 году. Когда контроль Мин распался, крестьянские повстанцы захватили столицу Мин в Пекине, но генерал Мин открыл Шанхайский проход для армии Цин, которая победила мятежников , захватила столицу и взяла на себя управление в 1644 году под руководством императора Шуньчжи и его принца-регента . Сопротивление со стороны режимов Мин и Восстание трех феодалов отсрочили полное завоевание до 1683 года. Будучи маньчжурским императором, император Канси (1661–1722) консолидировал контроль, наслаждался ролью конфуцианского правителя, покровительствовал буддизму (включая тибетский буддизм ), поощрял ученость , население и экономический рост. [15] Чиновники Хань работали под руководством или параллельно с маньчжурскими чиновниками. Чтобы сохранить выдающееся положение над своими соседями, Цин использовала и адаптировала систему данников, использовавшуюся предыдущими династиями, что позволило им продолжать преобладать в дипломатических отношениях со странами на ее периферии, такими как Корея Чосон и династия Ле во Вьетнаме, одновременно расширяя свой контроль над Внутренней Азией, включая Тибет , Монголию и Синьцзян .

Эпоха Высокого Цин достигла своего апогея во время правления императора Цяньлуна (1735–1796), который возглавил Десять великих завоевательных походов и лично руководил конфуцианскими культурными проектами . После его смерти династия столкнулась с внутренними восстаниями, экономическим упадком, официальной коррупцией, иностранным вторжением и нежеланием конфуцианской элиты менять свое мышление. С миром и процветанием население выросло до 400 миллионов, но налоги и государственные доходы были зафиксированы на низком уровне, что вскоре привело к финансовому кризису. После поражения Китая в Опиумных войнах западные колониальные державы вынудили правительство Цин подписать неравноправные договоры , предоставив им торговые привилегии, экстерриториальность и договорные порты под их контролем. Восстание тайпинов (1850–1864) и восстание дунган (1862–1877) в западном Китае привели к гибели более 20 миллионов человек от голода, болезней и войны. Реставрация Тунчжи в 1860-х годах принесла энергичные реформы и внедрение иностранных военных технологий в Движение за самоусиление . Поражение в Первой китайско-японской войне в 1895 году привело к потере сюзеренитета над Кореей и уступке Тайваня Японии . Амбициозная реформа Ста дней в 1898 году предлагала фундаментальные изменения, но вдовствующая императрица Цыси (1835–1908 ) отменила их в результате переворота .

В 1900 году антииностранные « боксеры » убили многих китайских христиан и иностранных миссионеров; в ответ иностранные державы вторглись в Китай и наложили штрафную контрибуцию . В ответ правительство инициировало беспрецедентные фискальные и административные реформы , включая выборы, новый правовой кодекс и отмену системы экзаменов . Сунь Ятсен и революционеры спорили с реформаторами и конституционными монархистами, такими как Кан Ювэй и Лян Цичао, о том, как преобразовать управляемую маньчжурами империю в модернизированное государство Хань. После смерти императора Гуансюя и Цыси в 1908 году маньчжурские консерваторы при дворе заблокировали реформы и оттолкнули реформаторов и местную элиту. Восстание Учан 10 октября 1911 года привело к Синьхайской революции . Отречение императора Сюаньтун 12 февраля 1912 года положило конец династии. В 1917 году он был ненадолго восстановлен в ходе так называемой Маньчжурской реставрации , однако это не было признано ни правительством Бэйян (1912–1928) Китайской Республики, ни международным сообществом.

Хун Тайцзи провозгласил Великую династию Цин в 1636 году. [16] Существуют конкурирующие объяснения относительно значения китайского иероглифа Цин (清; 'ясный', 'чистый') в этом контексте. Одна из теорий постулирует намеренное противопоставление Мин: иероглиф Мин (明; 'яркий') связан с огнем в китайской зодиакальной системе , в то время как Цин (清) связан с водой, иллюстрируя триумф Цин как завоевание огня водой. Имя, возможно, также обладало буддийским подтекстом проницательности и просветления, а также связью с бодхисаттвой Манджушри . [17] Ранние европейские авторы использовали термин «Тартар» без разбора для всех народов Северной Евразии, но в 17 веке католические миссионерские труды установили, что «Тартар» относится только к маньчжурам, а « Тартария » — к землям, которыми они правили, т. е. к Маньчжурии и прилегающим частям Внутренней Азии , [18] [19] находившимся под властью династии Цин до перехода от династии Мин к династии Цин .

После завоевания Китая маньчжуры определили свое государство как «Китай», что эквивалентно Чжунго (中國; «срединное царство») на китайском языке и Дулимбай Гурун на маньчжурском языке. [e] Императоры приравняли земли государства Цин (включая, среди прочего, современный Северо-Восточный Китай, Синьцзян, Монголию и Тибет) к «Китаю» как на китайском, так и на маньчжурском языках, определив Китай как многоэтническое государство и отвергнув идею о том, что только районы Хань были по праву частью «Китая». Правительство использовало «Китай» и «Цин» взаимозаменяемо для обозначения своего государства в официальных документах, [20] включая версии договоров и карты мира на китайском языке. [21] Термин «китайский народ» (中國人; Чжунгожэнь ; маньчжурский:ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ ᡳ

ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠ Dulimbai gurun-i niyalma ) относилось ко всем ханьским, маньчжурским и монгольским подданным империи Цин. [22] Когда Цин завоевала Джунгарию в 1759 году , она провозгласила в мемориале на маньчжурском языке, что новые земли были включены в «Китаю». [23] : 77 Правительство Цин излагало идеологию, согласно которой оно объединяло «внешние» неханьские народы, такие как различные популяции монголов, а также тибетцев, с «внутренними» ханьскими китайцами в «одну семью», объединенную в государстве Цин. Фразеология, такая как Zhōngwài yījiā (中外一家) и nèiwài yījiā (內外一家) — обе переводимые как «дома и за границей как одна семья» — использовалась для передачи этой идеи транскультурного единства, опосредованного Цин. [23] : 76–77

В английском языке династия Цин иногда известна как Маньчжурская династия [24] или транслитерируется как Цин, используя систему Уэйда-Джайлса .

Династия Цин была основана не народом хань , составляющим большинство населения Китая, а маньчжурами , потомками оседлого земледельческого народа, известного как чжурчжэни , тунгусо-языкого народа , который жил в регионе, ныне включающем китайские провинции Цзилинь и Хэйлунцзян . [25] Маньчжуров иногда ошибочно принимают за кочевой народ, [26] которым они не являлись. [27] [28]

Ранняя форма маньчжурского государства была основана Нурхаци , вождем небольшого племени чжурчжэней – Айсин-Гиоро – в Цзяньчжоу в начале 17 века. Нурхаци, возможно, провел некоторое время в ханьском доме в юности и стал свободно говорить на китайском и монгольском языках и читал китайские романы «Троецарствие» и «Речные заводи» . [29] [30] Будучи вассалом императоров Мин, он официально считал себя хранителем границы Мин и местным представителем династии Мин. [13] Нурхаци начал межплеменную вражду в 1582 году, которая переросла в кампанию по объединению соседних племен . Однако к 1616 году он достаточно консолидировал Цзяньчжоу, чтобы иметь возможность провозгласить себя ханом династии Поздняя Цзинь в отношении предыдущей династии Цзинь, управляемой чжурчжэнями . [31]

Два года спустя Нурхаци объявил о « Семи обидах » и открыто отказался от суверенитета Минского владычества, чтобы завершить объединение тех племен чжурчжэней, которые все еще были в союзе с императором Мин. После серии успешных сражений он перенес свою столицу из Хэту Ала в последовательно захваченные более крупные города Мин в Ляодуне: сначала Ляоян в 1621 году, затем Мукден (Шэньян) в 1625 году. [31] Кроме того, хорчины оказались полезным союзником в войне, предоставив чжурчжэням свой опыт в качестве кавалерийских лучников. Чтобы гарантировать этот новый союз, Нурхаци инициировал политику смешанных браков между чжурчжэньской и хорчинской знатью, в то время как те, кто сопротивлялся, были встречены военными действиями. Это типичный пример инициатив Нурхаци, которые в конечном итоге стали официальной политикой правительства Цин. В течение большей части периода Цин монголы оказывали военную помощь маньчжурам. [32]

Нурхаци умер в 1626 году, и ему наследовал его восьмой сын, Хун Тайцзи . Хотя Хун Тайцзи был опытным лидером и командиром двух Знамен, чжурчжэни потерпели поражение в 1627 году, отчасти из-за недавно приобретенных Мин португальских пушек . Чтобы устранить технологическое и численное неравенство, Хун Тайцзи в 1634 году создал свой собственный артиллерийский корпус, который отливал свои собственные пушки в европейском дизайне с помощью перебежчиков из Китая металлургов. Одним из определяющих событий правления Хун Тайцзи стало официальное принятие названия «маньчжур» для объединенного народа чжурчжэней в ноябре 1635 года. В 1635 году монгольские союзники маньчжуров были полностью включены в отдельную иерархию Знамени под прямым командованием маньчжуров. В апреле 1636 года монгольская знать Внутренней Монголии, маньчжурская знать и ханьский мандарин рекомендовали, чтобы Хун, как хан Поздней Цзинь, стал императором Великой Цин. [33] [34] Когда после поражения последнего кагана монголов ему вручили императорскую печать династии Юань , Хун Тайцзи переименовал свое государство из «Великой Цзинь» в «Великой Цин» и повысил свой статус с хана до императора , что свидетельствует об имперских амбициях, выходящих за рамки объединения маньчжурских территорий. Затем Хун Тайцзи снова вторгся в Корею в 1636 году.

Тем временем Хун Тайцзи создал элементарную бюрократическую систему, основанную на модели Мин. В 1631 году он создал шесть коллегий или министерств исполнительного уровня для надзора за финансами, кадрами, обрядами, армией, наказаниями и общественными работами. Однако изначально эти административные органы играли очень небольшую роль, и только накануне завершения завоевания десять лет спустя они начали выполнять свои правительственные функции. [35]

Хун Тайцзи укомплектовал свою бюрократию многими китайцами хань, включая недавно сдавшихся чиновников Мин, но обеспечил господство маньчжуров этнической квотой для высших назначений. Правление Хун Тайцзи также увидело фундаментальное изменение политики в отношении своих подданных ханьцев. Нурхаци обращался с ханьцами в Ляодуне в соответствии с тем, сколько у них было зерна: с теми, у кого было меньше 5-7 син, обращались плохо, а те, у кого было больше, вознаграждались имуществом. Из-за восстания ханьцев в 1623 году Нурхаци выступил против них и ввел дискриминационную политику и убийства против них. Он приказал, чтобы ханьцы, которые ассимилировались с чжурчжэнями (в Цзилине) до 1619 года, обращались наравне с чжурчжэнями, а не как покоренные ханьцы в Ляодуне. Хун Тайцзи осознавал необходимость привлечения китайцев ханьцев, объясняя нерешительным маньчжурам, почему ему нужно было снисходительно относиться к перебежчику Мин генералу Хун Чэнчжоу . [36] Хун Тайцзи включил ханьцев в чжурчжэньскую «нацию» как полноправных (если не первоклассных) граждан, обязанных нести военную службу. К 1648 году менее одной шестой знаменосцев имели маньчжурское происхождение. [37]

.jpg/440px-Dorgon,_the_Prince_Rui_(17th_century).jpg)

Хун Тайцзи внезапно умер в сентябре 1643 года. Поскольку чжурчжэни традиционно «выбирали» своего лидера через совет знати, в государстве Цин не было четкой системы преемственности. Главными претендентами на власть были старший сын Хун Тайцзи Хуге и единокровный брат Хун Тайцзи Доргон . Компромисс назначил пятилетнего сына Хун Тайцзи Фулина императором Шуньчжи , а Доргон стал регентом и фактическим лидером маньчжурской нации.

Тем временем чиновники правительства Мин боролись друг с другом, против фискального краха и против серии крестьянских восстаний . Они не смогли извлечь выгоду из спора о наследовании маньчжуров и присутствия несовершеннолетнего императора. В апреле 1644 года столица Пекин была разграблена коалицией повстанческих сил во главе с Ли Цзычэном , бывшим незначительным чиновником Мин, который основал недолговечную династию Шунь . Последний правитель Мин, император Чунчжэнь , покончил жизнь самоубийством, когда город пал перед мятежниками, что ознаменовало официальный конец династии.

Затем Ли Цзычэн повел повстанческие силы численностью около 200 000 человек [38] , чтобы противостоять У Саньгую на проходе Шанхай , ключевом проходе Великой стены , который защищал столицу. У Саньгуй, оказавшийся между китайской армией повстанцев, вдвое превосходящей его по численности, и иностранным врагом, с которым он сражался годами, связал свою судьбу со знакомыми маньчжурами. У Саньгуй, возможно, находился под влиянием жестокого обращения Ли Цзычэна с богатыми и культурными чиновниками, включая собственную семью Ли; говорили, что Ли забрал себе наложницу У Чэнь Юаньюань . У и Доргон объединились во имя мести за смерть императора Чунчжэня . Вместе два бывших врага встретились и победили повстанческие силы Ли Цзычэна в битве 27 мая 1644 года . [39]

Новые союзные армии захватили Пекин 6 июня. Император Шуньчжи был провозглашен « Сыном Неба » 30 октября. Маньчжуры, которые позиционировали себя как политических наследников императора Мин, победив Ли Цзычэна, завершили символический переход, проведя официальные похороны императора Чунчжэня. Однако завоевание остальной части Собственного Китая заняло еще семнадцать лет борьбы с приверженцами Мин, самозванцами и мятежниками. Последний самозванец Мин, принц Гуй , искал убежища у короля Бирмы Пиндейла Миня , но был передан экспедиционной армии Цин под командованием У Саньгуя, который вернул его в провинцию Юньнань и казнил в начале 1662 года.

Цин ловко воспользовался дискриминацией гражданских властей Мин против военных и подтолкнул военных Мин к дезертирству, распространяя сообщение о том, что маньчжуры ценят их навыки. [40] Знамена, состоящие из китайцев-ханьцев, дезертировавших до 1644 года, были отнесены к Восьми Знаменам, что давало им социальные и правовые привилегии. Перебежчики-ханьцы так сильно пополнили ряды Восьми Знамен, что этнические маньчжуры стали меньшинством — всего 16% в 1648 году, причем знаменосцы-ханьцы доминировали в 75%, а знаменосцы-монголы составляли остальное. [41] Китайские Знамена были вооружены пороховым оружием, таким как мушкеты и артиллерия. [42] Обычно войска перебежчиков-ханьцев использовались в качестве авангарда, в то время как знаменосцы-маньчжуры использовались преимущественно для быстрых ударов с максимальным эффектом, чтобы свести к минимуму потери этнических маньчжуров. [43]

Эта многонациональная сила завоевала Китай династии Мин для династии Цин. [44] Три офицера-знаменосца династии Ляодун, сыгравшие ключевые роли в завоевании южного Китая, были Шан Кэси, Гэн Чжунмин и Кун Юдэ, которые управляли южным Китаем автономно в качестве наместников династии Цин после завоевания. [45] Знаменосцы-ханьцы составляли большинство губернаторов в раннем Цин, стабилизируя правление Цин. [46] Для содействия этнической гармонии указ 1648 года разрешил гражданским мужчинам-ханьцам жениться на маньчжурских женщинах из Знамени с разрешения Совета по доходам, если они были зарегистрированными дочерьми чиновников или простолюдинов, или с разрешения капитана их знаменной роты, если они были незарегистрированными простолюдинами. Позже в династии политика, разрешающая смешанные браки, была отменена. [47]

Первые семь лет правления молодого императора Шуньчжи прошли под регентством Доргона. Из-за собственной политической неуверенности Доргон последовал примеру Хун Тайцзи, правя от имени императора за счет соперничающих маньчжурских принцев, многих из которых он понизил в должности или заключил в тюрьму. Прецеденты и пример Доргона отбрасывали длинную тень. Во-первых, маньчжуры вошли «к югу от стены», потому что Доргон решительно отреагировал на призыв У Саньгуя, затем, вместо того, чтобы разграбить Пекин, как это сделали мятежники, Доргон настоял, несмотря на протесты других маньчжурских принцев, на том, чтобы сделать его династической столицей и переназначить большинство чиновников Мин. Ни одна крупная китайская династия не захватывала напрямую столицу своей непосредственной предшественницы, но сохранение столицы Мин и бюрократии в неприкосновенности помогло быстро стабилизировать режим и ускорило завоевание остальной части страны. Затем Доргон резко сократил влияние евнухов и приказал маньчжурским женщинам не бинтовать ноги на китайский манер. [48]

Однако не все меры Доргона были одинаково популярны или легко реализуемы. Спорный указ от июля 1645 года (« приказ о стрижке ») заставил взрослых мужчин-ханьцев брить переднюю часть головы и зачесывать оставшиеся волосы в косичку , которую носили маньчжурские мужчины, под страхом смерти. [49] Популярное описание приказа было: «Чтобы сохранить волосы, вы теряете голову; чтобы сохранить голову, вы стрижете волосы». [48] Для маньчжуров эта политика была проверкой лояльности и помощью в различении друзей от врагов. Однако для китайцев-ханьцев это было унизительным напоминанием о власти Цин, которая бросала вызов традиционным конфуцианским ценностям. [50] Приказ вызвал сильное сопротивление в Цзяннане . [51] В ходе последовавших беспорядков было убито около 100 000 ханьцев. [52] [53] [54]

31 декабря 1650 года Доргон внезапно умер, ознаменовав начало личного правления императора Шуньчжи. Поскольку императору было всего 12 лет в то время, большинство решений от его имени принимала его мать, вдовствующая императрица Сяочжуан , которая оказалась искусным политическим деятелем. Хотя его поддержка была необходима для восхождения Шуньчжи, Доргон централизовал в своих руках так много власти, что стал прямой угрозой трону. Настолько, что после своей смерти он был удостоен необычного посмертного титула императора И (義皇帝), единственного случая в истории Цин, когда маньчжурский « принц крови » (親王) был столь почитаем. Однако через два месяца личного правления Шуньчжи Доргон был не только лишен своих титулов, но и его труп был эксгумирован и изуродован. [55] Падение Доргона в немилость также привело к чистке его семьи и соратников при дворе. Многообещающий старт Шуньчжи был прерван его ранней смертью в 1661 году в возрасте 24 лет от оспы . Ему наследовал его третий сын Сюанье, который правил как император Канси .

Маньчжуры отправили ханьских знаменосцев сражаться против сторонников Мин Коксинга в Фуцзяне. [56] Они выселили население из прибрежных районов, чтобы лишить сторонников Мин Коксинга ресурсов. Это привело к неправильному пониманию того, что маньчжуры «боялись воды». Ханьские знаменосцы вели бои и убивали, ставя под сомнение утверждение о том, что страх перед водой привел к эвакуации с побережья и запрету на морскую деятельность. [57] Хотя в стихотворении солдат, устраивавших резню в Фуцзяне, называют «варварами», и ханьская зеленая армия , и ханьские знаменосцы были вовлечены и совершили самую страшную бойню. [58] 400 000 солдат зеленой армии были использованы против Трех феодалов в дополнение к 200 000 знаменосцев. [59]

Шестидесятиоднолетнее правление императора Канси было самым продолжительным среди всех императоров Китая и ознаменовало начало эпохи « Высокого Цин », зенита социальной, экономической и военной мощи династии. Ранние правители Маньчжурии заложили две основы легитимности, которые помогают объяснить стабильность их династии. Первая — бюрократические институты и неоконфуцианская культура , которую они переняли у более ранних династий. [60] Правители Маньчжурии и китайская учено-чиновничья элита Хань постепенно пришли к соглашению друг с другом. Экзаменационная система открыла путь для этнических ханьцев к тому, чтобы стать чиновниками. Императорское покровительство словарю Канси продемонстрировало уважение к конфуцианскому обучению, в то время как Священный указ 1670 года эффективно превозносил конфуцианские семейные ценности. Однако его попытки отговорить китайских женщин от бинтования ног не увенчались успехом.

Вторым основным источником стабильности был внутриазиатский аспект их маньчжурской идентичности, который позволял им апеллировать к монгольским, тибетским и мусульманским подданным. [61] Цин использовал титул императора ( Хуанди или хуванди ) на китайском и маньчжурском языках (наряду с такими титулами, как Сын Неба и Эжен ), а среди тибетцев император Цин упоминался как « Император Китая » (или «Китайский император») и «Великий император» (или «Великий император Манджушри »), как, например, в Договоре Тапатхалия 1856 года , [62] [63] [64] в то время как среди монголов монарх Цин упоминался как Богда-хан [65] или «(маньчжурский) император», а среди мусульманских подданных во Внутренней Азии правитель Цин упоминался как «Каган Китая» (или « Китайский каган »). [66] Император Цяньлун изобразил себя как буддийского мудреца-правителя , покровителя тибетского буддизма [67] в надежде умилостивить монголов и тибетцев. [68] Император Канси также приветствовал при своем дворе иезуитских миссионеров, которые впервые прибыли в Китай во времена династии Мин.

Правление Канси началось, когда ему было семь лет. Чтобы предотвратить повторение монополизации власти Доргоном, на смертном одре его отец поспешно назначил четырех регентов, которые не были тесно связаны с императорской семьей и не имели никаких прав на трон. Однако благодаря случайности и махинациям Обой , самый младший из четырех, постепенно достиг такого господства, что стал потенциальной угрозой. В 1669 году Канси с помощью хитрости разоружил и заключил в тюрьму Обоя — значительная победа для пятнадцатилетнего императора.

Молодой император также столкнулся с трудностями в сохранении контроля над своим королевством. Три генерала Мин, выделенные за их вклад в установление династии, получили губернаторские должности в Южном Китае. Они становились все более автономными, что привело к Восстанию трех феодалов , которое длилось восемь лет. Канси смог объединить свои силы для контратаки, возглавляемой новым поколением маньчжурских генералов. К 1681 году правительство Цин установило контроль над разоренным Южным Китаем, на восстановление которого ушло несколько десятилетий. [69]

Чтобы расширить и укрепить контроль династии в Центральной Азии, император Канси лично возглавил ряд военных кампаний против джунгаров во Внешней Монголии . Император Канси изгнал вторгшиеся силы Галдана из этих регионов, которые затем были включены в состав империи. Галдан в конечном итоге был убит в Джунгаро-цинской войне . [70] В 1683 году войска Цин получили капитуляцию Формозы ( Тайвань) от Чжэн Кэшуана , внука Коксинга , который завоевал Тайвань у голландских колонистов в качестве базы против Цин. Завоевание Тайваня освободило силы Канси для серии сражений за Албазин , дальневосточный форпост Российского царства . Нерчинский договор 1689 года был первым официальным договором Китая с европейской державой и поддерживал мир на границе большую часть двух столетий. После смерти Галдана его последователи, как приверженцы тибетского буддизма, попытались контролировать выбор следующего Далай-ламы . Канси отправил две армии в Лхасу , столицу Тибета, и поставил Далай-ламу, симпатизирующего Цин. [71]

Правление императора Юнчжэна (годы правления 1723–1735) и его сына, императора Цяньлуна (годы правления 1735–1796), ознаменовало пик могущества Цин. Однако, как говорит историк Джонатан Спенс, империя к концу правления Цяньлуна была «подобна солнцу в полдень». Среди «множества славы», пишет он, «становились очевидными признаки упадка и даже краха». [72]

После смерти императора Канси зимой 1722 года его четвертый сын, принц Юн (雍親王), стал императором Юнчжэн. Он чувствовал необходимость срочного решения проблем, накопившихся в последние годы жизни его отца. [73] По словам одного недавнего историка, он был «суровым, подозрительным и ревнивым, но чрезвычайно способным и находчивым», [74] а по словам другого, он оказался «первоклассным государственным деятелем раннего Нового времени». [75] Во-первых, он пропагандировал конфуцианскую ортодоксальность и преследовал неортодоксальные секты. В 1723 году он объявил христианство вне закона и изгнал большинство христианских миссионеров. [76] Он расширил систему Дворцовых мемориалов своего отца , которая доставляла откровенные и подробные отчеты о местных условиях непосредственно трону, не перехватываясь бюрократией, и создал небольшой Большой совет личных советников, который в конечном итоге превратился в фактический кабинет императора для остальной части династии. Он проницательно заполнил ключевые должности чиновниками из маньчжурских и ханьских китайцев, которые зависели от его покровительства. Когда он начал осознавать масштабы финансового кризиса, Юнчжэн отверг снисходительный подход своего отца к местной элите и принудительно взимал земельный налог. Увеличенные доходы должны были быть использованы на «деньги для питания честности» среди местных чиновников и на местное орошение, школы, дороги и благотворительность. Хотя эти реформы были эффективны на севере, на юге и в нижней части долины Янцзы существовали давно устоявшиеся сети чиновников и землевладельцев. Юнчжэн отправил опытных маньчжурских комиссаров, чтобы проникнуть в дебри фальсифицированных земельных кадастров и кодированных бухгалтерских книг, но они столкнулись с уловками, пассивностью и даже насилием. Финансовый кризис продолжался. [77]

Юнчжэн также унаследовал дипломатические и стратегические проблемы. Команда, состоящая полностью из маньчжуров, составила Кяхтинский договор (1727) , чтобы укрепить дипломатическое взаимопонимание с Россией. В обмен на территорию и торговые права Цин получил бы свободу действий в решении ситуации в Монголии. Затем Юнчжэн обратился к этой ситуации, где джунгары угрожали возродиться, и к юго-западу, где местные вожди мяо сопротивлялись экспансии Цин. Эти кампании истощили казну, но установили контроль императора над армией и военными финансами. [78]

Когда император Юнчжэн умер в 1735 году, его сын принц Бао (寶親王) стал императором Цяньлуном. Цяньлун лично возглавил Десять великих кампаний по расширению военного контроля на территорию современных Синьцзяна и Монголии , подавляя восстания и мятежи в Сычуани и Южном Китае, одновременно расширяя контроль над Тибетом. Император Цяньлун запустил несколько амбициозных культурных проектов, включая составление Полной библиотеки четырех сокровищниц (или Сыку Цюаньшу ), крупнейшего собрания книг в истории Китая. Тем не менее, Цяньлун использовал литературную инквизицию, чтобы заставить замолчать оппозицию. [79] Под внешним процветанием и императорской уверенностью последние годы правления Цяньлуна были отмечены безудержной коррупцией и пренебрежением. Хэшэнь , красивый молодой фаворит императора, воспользовался снисходительностью императора, чтобы стать одним из самых коррумпированных чиновников в истории династии. [80] Сын Цяньлуна, император Цзяцин (годы правления 1796–1820), в конце концов заставил Хэшэня покончить жизнь самоубийством.

Население находилось на стагнации в первой половине XVII века из-за гражданских войн и эпидемий, но процветание и внутренняя стабильность постепенно изменили эту тенденцию. Император Цяньлун сетовал на ситуацию, заявляя: «Население продолжает расти, но земля — нет». Введение новых культур из Америки, таких как картофель и арахис , также позволило улучшить снабжение продовольствием, так что общая численность населения Китая в XVIII веке выросла со 100 миллионов до 300 миллионов человек. Вскоре фермеры были вынуждены работать на все меньших участках земли более интенсивно. Единственной оставшейся частью империи, которая имела пахотные земли, была Маньчжурия , где провинции Цзилинь и Хэйлунцзян были отгорожены стеной как родина маньчжуров. Несмотря на запреты, к XVIII веку ханьцы устремились в Маньчжурию как нелегально, так и легально через Великую стену и Ивовый частокол .

В 1796 году вспыхнуло открытое восстание среди последователей Общества Белого Лотоса , которые обвинили чиновников Цин, заявив, что «чиновники заставили людей восстать». Чиновников в других частях страны также обвиняли в коррупции, неспособности наполнить зернохранилища для помощи голодающим, плохом содержании дорог и водопроводных сооружений и бюрократической фракционности. Вскоре последовали восстания мусульман «новой секты» против местных мусульманских чиновников и племени Мяо на юго-западе Китая. Восстание Белого Лотоса продолжалось восемь лет, до 1804 года, когда плохо организованные, коррумпированные и жестокие кампании наконец положило ему конец. [81]

.jpg/440px-Destroying_Chinese_war_junks,_by_E._Duncan_(1843).jpg)

В начале династии Китайская империя продолжала быть гегемоном в Восточной Азии . Хотя формального министерства иностранных дел не существовало, Лифань Юань отвечал за отношения с монголами и тибетцами во Внутренней Азии , в то время как система данников , свободный набор институтов и обычаев, перенятых у Мин, теоретически регулировала отношения со странами Восточной и Юго-Восточной Азии . Нерчинский договор , подписанный в 1689 году, стабилизировал отношения с царской Россией .

Однако в течение XVIII века европейские империи постепенно расширялись по всему миру, поскольку европейские государства развивали экономику, основанную на морской торговле, колониальной добыче и достижениях в области технологий. Династия столкнулась с новыми развивающимися концепциями международной системы и межгосударственными отношениями. Европейские торговые посты расширили территориальный контроль в соседней Индии и на островах, которые сейчас являются Индонезией . Ответом Цин, успешным на некоторое время, стало создание Кантонской системы в 1756 году, которая ограничила морскую торговлю этим городом (современный Гуанчжоу ) и предоставила монопольные торговые права частным китайским торговцам . Британская Ост-Индская компания и Голландская Ост-Индская компания задолго до этого получили аналогичные монопольные права от своих правительств.

В 1793 году Британская Ост-Индская компания при поддержке британского правительства отправила дипломатическую миссию в Китай во главе с лордом Джорджем Макартни , чтобы открыть торговлю и поставить отношения на основе равенства. Императорский двор считал торговлю второстепенным интересом, тогда как британцы видели в морской торговле ключ к своей экономике. Император Цяньлун сказал Макартни: «цари бесчисленных народов приходят по суше и по морю со всевозможными драгоценностями», и «следовательно, нет ничего, в чем мы нуждаемся...» [82]

Поскольку у Китая было мало спроса на европейские товары, Европа платила серебром за китайские товары, дисбаланс, который беспокоил меркантилистские правительства Великобритании и Франции. Растущий китайский спрос на опиум стал средством решения проблемы. Британская Ост-Индская компания значительно расширила свое производство в Бенгалии. Император Даогуан , обеспокоенный как оттоком серебра, так и ущербом, который курение опиума наносило его подданным, приказал Линь Цзэсюю положить конец торговле опиумом. Линь конфисковал запасы опиума без компенсации в 1839 году, что заставило Британию отправить военную экспедицию в следующем году. Первая опиумная война выявила устаревшее состояние китайской армии. Цинский флот, полностью состоящий из деревянных парусных джонок , был серьезно уступал современной тактике и огневой мощи британского Королевского флота . Британские солдаты, используя передовые мушкеты и артиллерию, легко превзошли маневренность и огневую мощь войск Цин в наземных сражениях. Капитуляция Цин в 1842 году стала решающим, унизительным ударом. Нанкинский договор , первый из « неравноправных договоров », требовал военных репараций, вынудил Китай открыть договорные порты Кантон , Амой , Фучжоу , Нинбо и Шанхай для западной торговли и миссионеров, а также уступить остров Гонконг Британии. Он выявил слабости правительства Цин и спровоцировал восстания против режима.

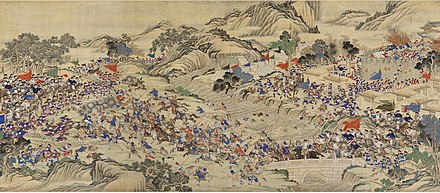

Восстание тайпинов в середине 19 века стало первым крупным примером антиманьчжурских настроений . Восстание началось под руководством Хун Сюцюаня (1814–1864), разочарованного кандидата на государственную службу, который под влиянием христианских учений имел ряд видений и считал себя сыном Бога, младшим братом Иисуса Христа, посланным реформировать Китай. Друг Хун, Фэн Юньшань, использовал идеи Хун для организации новой религиозной группы, Общества поклоняющихся Богу (Бай Шанди Хуэй), которую он сформировал среди обедневших крестьян провинции Гуанси. [83] На фоне широко распространенных социальных беспорядков и усиливающегося голода восстание не только представляло самую серьезную угрозу правителям Цин, его также называли «самой кровавой гражданской войной всех времен»; за четырнадцать лет с 1850 по 1864 год погибло от 20 до 30 миллионов человек. [84] Хун Сюцюань, неудавшийся кандидат на государственную службу , в 1851 году поднял восстание в провинции Гуйчжоу и основал Небесное царство Тайпинов с самим Хуном в качестве короля. Хун объявил, что у него были видения Бога и что он был братом Иисуса Христа. Рабство, сожительство, брак по договоренности, курение опиума, бинтование ног, судебные пытки и поклонение идолам были запрещены. Однако успех привел к внутренним распрям, дезертирам и коррупции. Кроме того, британские и французские войска, оснащенные современным оружием, пришли на помощь имперской армии Цин. Тем не менее, только в 1864 году армиям Цин под командованием Цзэн Гофаня удалось подавить восстание. После начала этого восстания произошли также восстания мусульман и народа мяо Китая против династии Цин, наиболее заметными из которых были восстание мяо (1854–1873) в Гуйчжоу , восстание Пантхая (1856–1873) в Юньнани и восстание дунган (1862–1877) на северо-западе.

Западные державы, в значительной степени неудовлетворенные Нанкинским договором, оказали неохотную поддержку правительству Цин во время восстаний тайпинов и нянь . Доход Китая резко упал во время войн, поскольку огромные площади сельскохозяйственных угодий были уничтожены, миллионы жизней были потеряны, и бесчисленные армии были собраны и оснащены для борьбы с мятежниками. В 1854 году Великобритания попыталась пересмотреть Нанкинский договор, включив в него положения, разрешающие британской торговле доступ к китайским рекам и создание постоянного британского посольства в Пекине.

In 1856, Qing authorities, in searching for a pirate, boarded a ship, the Arrow, which the British claimed had been flying the British flag, an incident which led to the Second Opium War. In 1858, facing no other options, the Xianfeng Emperor agreed to the Treaty of Tientsin, which contained clauses deeply insulting to the Chinese, such as a demand that all official Chinese documents be written in English and a proviso granting British warships unlimited access to all navigable Chinese rivers.

Ratification of the treaty in the following year led to a resumption of hostilities. In 1860, with Anglo-French forces marching on Beijing, the emperor and his court fled the capital for the imperial hunting lodge at Rehe. Once in Beijing, the Anglo-French forces looted and burned the Old Summer Palace and, in an act of revenge for the arrest, torture, and execution of the English diplomatic mission.[85] Prince Gong, a younger half-brother of the emperor, who had been left as his brother's proxy in the capital, was forced to sign the Convention of Beijing. The humiliated emperor died the following year at Rehe.

Yet the dynasty rallied. Chinese generals and officials such as Zuo Zongtang led the suppression of rebellions and stood behind the Manchus. When the Tongzhi Emperor came to the throne at the age of five in 1861, these officials rallied around him in what was called the Tongzhi Restoration. Their aim was to adopt Western military technology in order to preserve Confucian values. Zeng Guofan, in alliance with Prince Gong, sponsored the rise of younger officials such as Li Hongzhang, who put the dynasty back on its feet financially and instituted the Self-Strengthening Movement. The reformers then proceeded with institutional reforms, including China's first unified ministry of foreign affairs, the Zongli Yamen; allowing foreign diplomats to reside in the capital; establishment of the Imperial Maritime Customs Service; the formation of modernized armies, such as the Beiyang Army, as well as a navy; and the purchase from Europeans of armament factories.[86]

The dynasty lost control of peripheral territories bit by bit. In return for promises of support against the British and the French, the Russian Empire took large chunks of territory in the Northeast in 1860. The period of cooperation between the reformers and the European powers ended with the Tientsin Massacre of 1870, which was incited by the murder of French nuns set off by the belligerence of local French diplomats. Starting with the Cochinchina Campaign in 1858, France expanded control of Indochina. By 1883, France was in full control of the region and had reached the Chinese border. The Sino-French War began with a surprise attack by the French on the Chinese southern fleet at Fuzhou. After that the Chinese declared war on the French. A French invasion of Taiwan was halted and the French were defeated on land in Tonkin at the Battle of Bang Bo. However Japan threatened to enter the war against China due to the Gapsin Coup and China chose to end the war with negotiations. The war ended in 1885 with the Treaty of Tientsin (1885) and the Chinese recognition of the French protectorate in Vietnam.[87] Some Russian and Chinese gold miners also established a short-lived proto-state known as the Zheltuga Republic (1883–1886) in the Amur river basin, which was however soon crushed by the Qing forces.[88]

In 1884, Qing China obtained concessions in Korea, such as the Chinese concession of Incheon,[89] but the pro-Japanese Koreans in Seoul led the Gapsin Coup. Tensions between China and Japan rose after China intervened to suppress the uprising. Japanese Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi and Li Hongzhang signed the Convention of Tientsin, an agreement to withdraw troops simultaneously, but the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895 was a military humiliation. The Treaty of Shimonoseki recognized Korean independence and ceded Taiwan and the Pescadores to Japan. The terms might have been harsher, but when a Japanese citizen attacked and wounded Li Hongzhang, an international outcry shamed the Japanese into revising them. The original agreement stipulated the cession of Liaodong Peninsula to Japan, but Russia, with its own designs on the territory, along with Germany and France, in the Triple Intervention, successfully put pressure on the Japanese to abandon the peninsula.

These years saw an evolution in the participation of Empress Dowager Cixi (Wade–Giles: Tz'u-Hsi) in state affairs. She entered the imperial palace in the 1850s as a concubine to the Xianfeng Emperor (r. 1850–1861) and came to power in 1861 after her five-year-old son, the Tongzhi Emperor ascended the throne. She, the Empress Dowager Ci'an (who had been Xianfeng's empress), and Prince Gong (a son of the Daoguang Emperor), staged a coup that ousted several regents for the boy emperor. Between 1861 and 1873, she and Ci'an served as regents, choosing the reign title "Tongzhi" (ruling together). Following the emperor's death in 1875, Cixi's nephew, the Guangxu Emperor, took the throne, in violation of the dynastic custom that the new emperor be of the next generation, and another regency began. In the spring of 1881, Ci'an suddenly died, aged only forty-three, leaving Cixi as sole regent.[90]

From 1889, when Guangxu began to rule in his own right, to 1898, the Empress Dowager lived in semi-retirement, spending the majority of the year at the Summer Palace. In 1897, two German Roman Catholic missionaries were murdered in southern Shandong province (the Juye Incident). Germany used the murders as a pretext for a naval occupation of Jiaozhou Bay. The occupation prompted a "scramble for concessions" in 1898, which included the German lease of Jiaozhou Bay, the Russian lease of Liaodong, the British lease of the New Territories of Hong Kong, and the French lease of Guangzhouwan.

In the wake of these external defeats, the Guangxu Emperor initiated the Hundred Days' Reform of 1898. Newer, more radical advisers such as Kang Youwei were given positions of influence. The emperor issued a series of edicts and plans were made to reorganize the bureaucracy, restructure the school system, and appoint new officials. Opposition from the bureaucracy was immediate and intense. Although she had been involved in the initial reforms, the Empress Dowager stepped in to call them off, arrested and executed several reformers, and took over day-to-day control of policy. Yet many of the plans stayed in place, and the goals of reform were implanted.[91]

Drought in North China, combined with the imperialist designs of European powers and the instability of the Qing government, created background conditions for the Boxers. In 1900, local groups of Boxers proclaiming support for the Qing dynasty murdered foreign missionaries and large numbers of Chinese Christians, then converged on Beijing to besiege the Foreign Legation Quarter. A coalition of European, Japanese, and Russian armies (the Eight-Nation Alliance) then entered China without diplomatic notice, much less permission. Cixi declared war on all of these nations, only to lose control of Beijing after a short, but hard-fought campaign. She fled to Xi'an. The victorious allies then enforced their demands on the Qing government, including compensation for their expenses in invading China and execution of complicit officials, via the Boxer Protocol.[92]

The defeat by Japan in 1895 created a sense of crisis which the failure of the 1898 reforms and the disasters of 1900 only exacerbated. Cixi in 1901 moved to mollify the foreign community, called for reform proposals, and initiated a set of "New Policies", also known as the Late Qing reforms. Over the next few years the reforms included the restructuring of the national education, judicial, and fiscal systems, the most dramatic of which was the abolition of the imperial examinations in 1905.[93] The court directed a constitution to be drafted, and provincial elections were held, the first in China's history.[94] Sun Yat-sen and revolutionaries debated reform officials and constitutional monarchists such as Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao over how to transform the Manchu-ruled empire into a modernised Han Chinese state.[95]

The Guangxu Emperor died on 14 November 1908 and Cixi died the following day. Puyi, the oldest son of Zaifeng, Prince Chun, and nephew to the childless Guangxu Emperor, was appointed successor at the age of two, leaving Zaifeng with the regency. Zaifeng forced Yuan Shikai to resign. The Qing dynasty became a constitutional monarchy on 8 May 1911, when Zaifeng created a "responsible cabinet" led by Yikuang, Prince Qing. However, the cabinet became known as the "royal cabinet" because among the thirteen cabinet members, five were members of the imperial family or Aisin-Gioro relatives.[96]

The Wuchang Uprising of 10 October 1911 set off a series of uprisings. By November, 14 of the 22 provinces had rejected Qing rule. This led to the creation of the Republic of China, in Nanjing on 1 January 1912, with Sun Yat-sen as its provisional head. Seeing a desperate situation, the Qing court brought Yuan Shikai back to power. His Beiyang Army crushed the revolutionaries in Wuhan at the Battle of Yangxia. After taking the position of Prime Minister he created his own cabinet, with the support of Empress Dowager Longyu. However, Yuan Shikai decided to cooperate with Sun Yat-sen's revolutionaries to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

On 12 February 1912, Longyu issued the abdication of the child emperor Puyi leading to the fall of the Qing dynasty under the pressure of Yuan Shikai's Beiyang army despite objections from conservatives and royalist reformers.[97] This brought an end to over 2,000 years of Imperial China and began a period of instability. In July 1917, there was an abortive attempt to restore the Qing dynasty led by Zhang Xun. Puyi was allowed to live in the Forbidden City after his abdication until 1924, when he moved to the Japanese concession in Tianjin. The Empire of Japan invaded Northeast China and founded Manchukuo there in 1932, with Puyi as its emperor. After the invasion of Northeast China to fight Japan by the Soviet Union, Manchukuo fell in 1945.

The early Qing emperors adopted the bureaucratic structures and institutions from the preceding Ming dynasty but split rule between Han Chinese and Manchus, with some positions also given to Mongols.[98] Like previous dynasties, the Qing recruited officials via the imperial examination system, until the system was abolished in 1905. The Qing divided the positions into civil and military positions, each having nine grades or ranks, each subdivided into a and b categories. Civil appointments ranged from an attendant to the emperor or a Grand Secretary in the Forbidden City (highest) to being a prefectural tax collector, deputy jail warden, deputy police commissioner, or tax examiner. Military appointments ranged from being a field marshal or chamberlain of the imperial bodyguard to a third class sergeant, corporal or a first or second class private.[99]

While the Qing dynasty tried to maintain the traditional tributary system of China, by the 19th century Qing China had become part of a European-style community of sovereign states[100] and established official diplomatic relations with more than twenty countries around the world before its downfall, and since the 1870s it established legations and consulates known as the "Chinese Legation", "Imperial Consulate of China", "Imperial Chinese Consulate (General)" or similar names in seventeen countries, namely the Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Cuba, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, Panama, Peru, Portugal, Russia, Spain, United Kingdom (or the British Empire) and the United States.

The formal structure of the Qing government centered on the Emperor as the absolute ruler, who presided over six Boards (Ministries[f]), each headed by two presidents[g] and assisted by four vice presidents.[h] In contrast to the Ming system, however, Qing ethnic policy dictated that appointments were split between Manchu noblemen and Han officials who had passed the highest levels of the state examinations. The Grand Secretariat,[i] which had been an important policy-making body under the Ming, lost its importance during the Qing and evolved into an imperial chancery. The institutions which had been inherited from the Ming formed the core of the Qing "Outer Court", which handled routine matters and was located in the southern part of the Forbidden City.[101]

In order not to let the routine administration take over the running of the empire, the Qing emperors made sure that all important matters were decided in the "Inner Court", which was dominated by the imperial family and Manchu nobility and which was located in the northern part of the Forbidden City. The core institution of the inner court was the Grand Council.[j] It emerged in the 1720s under the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor as a body charged with handling Qing military campaigns against the Mongols, but soon took over other military and administrative duties, centralizing authority under the crown.[102] The Grand Councillors[k] served as a sort of privy council to the emperor.

From the early Qing, the central government was characterized by a system of dual appointments by which each position in the central government had a Manchu and a Han Chinese assigned to it. The Han Chinese appointee was required to do the substantive work and the Manchu to ensure Han loyalty to Qing rule.[103] While the Qing government was established as an absolute monarchy like previous dynasties in China, by the early 20th century however the Qing court began to move towards a constitutional monarchy,[104] with government bodies like the Advisory Council established and a parliamentary election to prepare for a constitutional government.[105][106]

There was also another government institution called Imperial Household Department which was unique to the Qing dynasty. It was established before the fall of the Ming, but it became mature only after 1661, following the death of the Shunzhi Emperor and the accession of his son, the Kangxi Emperor.[107] The department's original purpose was to manage the internal affairs of the imperial family and the activities of the inner palace (in which tasks it largely replaced eunuchs), but it also played an important role in Qing relations with Tibet and Mongolia, engaged in trading activities (jade, ginseng, salt, furs, etc.), managed textile factories in the Jiangnan region, and even published books.[108] Relations with the Salt Superintendents and salt merchants, such as those at Yangzhou, were particularly lucrative, especially since they were direct, and did not go through absorptive layers of bureaucracy. The department was manned by booi,[l] or "bondservants", from the Upper Three Banners.[109] By the 19th century, it managed the activities of at least 56 subagencies.[107][110]

.jpg/440px-Empire_Chinois,_Japon_(1832).jpg)

Qing China reached its largest extent during the 18th century, when it ruled China proper (eighteen provinces) as well as the areas of present-day Northeast China, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet, at approximately 13 million km2 in size. There were originally 18 provinces, all of which in China proper, but later this number was increased to 22, with Manchuria and Xinjiang being divided or turned into provinces. Taiwan, originally part of Fujian province, became a province of its own in the 19th century,[111] but was ceded to the Empire of Japan following the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895.[112]

The Qing organization of provinces was based on the fifteen administrative units set up by the Ming dynasty, later made into eighteen provinces by splitting for example, Huguang into Hubei and Hunan provinces. The provincial bureaucracy continued the Yuan and Ming practice of three parallel lines, civil, military, and censorate, or surveillance. Each province was administered by a governor (巡撫, xunfu) and a provincial military commander (提督, tidu). Below the province were prefectures (府, fu) operating under a prefect (知府, zhīfǔ), followed by subprefectures under a subprefect. The lowest unit was the county, overseen by a county magistrate. The eighteen provinces are also known as "China proper". The position of viceroy or governor-general (總督, zongdu) was the highest rank in the provincial administration. There were eight regional viceroys in China proper, each usually took charge of two or three provinces. The Viceroy of Zhili, who was responsible for the area surrounding the capital Beijing, is usually considered as the most honorable and powerful viceroy among the eight.

By the mid-18th century, the Qing had successfully put outer regions such as Inner and Outer Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang under its control. Imperial commissioners and garrisons were sent to Mongolia and Tibet to oversee their affairs. These territories were also under supervision of a central government institution called Lifan Yuan. Qinghai was also put under direct control of the Qing court. Xinjiang, also known as Chinese Turkestan, was subdivided into the regions north and south of the Tian Shan mountains, also known today as Dzungaria and Tarim Basin respectively, but the post of Ili General was established in 1762 to exercise unified military and administrative jurisdiction over both regions. Dzungaria was fully opened to Han migration by the Qianlong Emperor from the beginning. Han migrants were at first forbidden from permanently settling in the Tarim Basin but were the ban was lifted after the invasion by Jahangir Khoja in the 1820s. Likewise, Manchuria was also governed by military generals until its division into provinces, though some areas of Xinjiang and Northeast China were lost to the Russian Empire in the mid-19th century. Manchuria was originally separated from China proper by the Inner Willow Palisade, a ditch and embankment planted with willows intended to restrict the movement of the Han Chinese, as the area was off-limits to civilian Han Chinese until the government started colonizing the area, especially since the 1860s.

With respect to these outer regions, the Qing maintained imperial control, with the emperor acting as Mongol khan, patron of Tibetan Buddhism and protector of Muslims. However, Qing policy changed with the establishment of Xinjiang province in 1884. During The Great Game era, taking advantage of the Dungan revolt in northwest China, Yakub Beg invaded Xinjiang from Central Asia with support from the British Empire, and made himself the ruler of the kingdom of Kashgaria. The Qing court sent forces to defeat Yaqub Beg and Xinjiang was reconquered, and then the political system of China proper was formally applied onto Xinjiang. The Kumul Khanate, which was incorporated into the Qing dynasty as a vassal after helping Qing defeat the Zunghars in 1757, maintained its status after Xinjiang turned into a province through the end of the dynasty in the Xinhai Revolution up until 1930.[113] In the early 20th century, Britain sent an expedition force to Tibet and forced Tibetans to sign a treaty. The Qing court responded by asserting Chinese sovereignty over Tibet,[114] resulting in the 1906 Anglo-Chinese Convention signed between Britain and China. The British agreed not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet, while China engaged not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet.[115] The Qing government also turned Manchuria into three provinces in the early 20th century, officially known as the "Three Northeast Provinces", and established the post of Viceroy of the Three Northeast Provinces to oversee these provinces.

The population grew in numbers, density, and mobility. The population grew from roughly 150 million in 1700, about what it had been a century before, then doubled over the next century, and reached a height of 450 million on the eve of the Taiping Rebellion in 1850.[116] The spread of New World crops, such as maize, peanuts, sweet potatoes, and potatoes decreased the number of deaths from malnutrition. Diseases such as smallpox were brought under control by an increase in inoculations. In addition, infant deaths were decreased due to improvements in birthing techniques performed by doctors and midwives and an increase in medical books available to the public.[117] Government campaigns decreased the incidence of infanticide. In Europe population growth in this period was greatest in the cities, but in China growth in cities and the lower Yangzi was low. The greatest growth was in the borderlands and the highlands, where farmers could clear large tracts of marshlands and forests.[118]

The population was also remarkably mobile, perhaps more so than at any time in Chinese history. Indeed, the Qing government did far more to encourage mobility than to discourage it. Millions of Han Chinese migrated to Yunnan and Guizhou in the 18th century, and also to Taiwan. After the conquests of the 1750s and 1760s, the court organized agricultural colonies in Xinjiang. This mobility also included the organized movement of Qing subjects overseas, largely to Southeastern Asia, to pursue trade and other economic opportunities.[118]

Manchuria, however, was formally closed to Han settlement by the Willow Palisade, with the exception of some bannermen.[119] Nonetheless, by 1780, Han Chinese had become 80% of the population.[120] The relatively low populated territory was vulnerable as the Russian Empire demanded the Amur Annexation annexing Outer Manchuria. In response, the Qing officials such as Tepuqin (特普欽), the Military Governor of Heilongjiang in 1859–1867, made proposals (1860) to open parts of Guandong for Chinese civilian farmer settlers in order to oppose further possible annexations.[121] In the later 19th century, Manchuria was opened up for Han settlers leading to a more extensive migration,[122] which was called Chuang Guandong (simplified Chinese: 闯关东; traditional Chinese: 闖關東) literally "Crashing into Guandong" with Guandong being an older name for Manchuria.[123] At the end of the 19th century and turn of the 20th century, to counteract increasing Russian influence, the Qing Dynasty abolished the existing administrative system in Manchuria and reclassified all immigrants to the region as Han (Chinese) instead of minren (民人, civilians, non-bannermen), while replacing provincial generals with provincial governors. From 1902 to 1911, seventy civil administrations were created due to the increasing population of Manchuria.[124]

According to statute, Qing society was divided into relatively closed estates, of which in most general terms there were five. Apart from the estates of the officials, the comparatively minuscule aristocracy, and the degree-holding literati, there also existed a major division among ordinary Chinese between commoners and people with inferior status.[125] They were divided into two categories: one of them, the good "commoner" people, the other "mean" people who were seen as debased and servile. The majority of the population belonged to the first category and were described as liangmin, a legal term meaning good people, as opposed to jianmin meaning the mean (or ignoble) people. Qing law explicitly stated that the traditional four occupational groups of scholars, farmers, artisans and merchants were "good", or having a status of commoners. On the other hand, slaves or bondservants, entertainers (including prostitutes and actors), tattooed criminals, and those low-level employees of government officials were the "mean people". Mean people were legally inferior to commoners and suffered unequal treatments, such as being forbidden to take the imperial examination.[126] Furthermore, such people were usually not allowed to marry with free commoners and were even often required to acknowledge their abasement in society through actions such as bowing. However, throughout the Qing dynasty, the emperor and his court, as well as the bureaucracy, worked towards reducing the distinctions between the debased and free but did not completely succeed even at the end of its era in merging the two classifications together.[127]

Although there had been no powerful hereditary aristocracy since the Song dynasty, the gentry (shenshi), like their British counterparts, enjoyed imperial privileges and managed local affairs. The status of this scholar-official was defined by passing at least the first level of civil service examinations and holding a degree, which qualified him to hold imperial office, although he might not actually do so. The gentry member could legally wear gentry robes and could talk to officials as equals. Informally, the gentry then presided over local society and could use their connections to influence the magistrate, acquire land, and maintain large households. The gentry thus included not only males holding degrees but also their wives and some of their relatives.[128]

The gentry class was divided into groups. Not all who held office were literati, as merchant families could purchase degrees, and not all who passed the exams found employment as officials, since the number of degree-holders was greater than the number of openings. The gentry class also differed in the source and amount of their income. Literati families drew income from landholding, as well as from lending money. Officials drew a salary, which, as the years went by, were less and less adequate, leading to widespread reliance on "squeeze", irrgular payments. Those who prepared for but failed the exams, like those who passed but were not appointed to office, could become tutors or teachers, private secretaries to sitting officials, administrators of guilds or temples, or other positions that required literacy. Others turned to fields such as engineering, medicine, or law, which by the nineteenth century demanded specialized learning. By the nineteenth century, it was no longer shameful to become an author or publisher of fiction.[129]

The Qing gentry were marked as much by their aspiration to a cultured lifestyle as by their legal status. They lived more refined and comfortable lives than the commoners and used sedan-chairs to travel any significant distance. They often showed off their learning by collecting objects such as scholars' stones, porcelain or pieces of art for their beauty, which set them off from less cultivated commoners.[130]

By the Qing, the building block of society was patrilineal kinship, that is, the local family lineage with descent through the male line, often translated as "clan". A shift in marital practices, identity and loyalty had begun during the Song dynasty when the civil service examination began to replace nobility and inheritance as a means for gaining status. Instead of intermarrying within aristocratic elites of the same social status, they tended to form marital alliances with nearby families of the same or higher wealth, and established the local people's interests as first and foremost which helped to form intermarried townships.[131] The neo-Confucian ideology, especially the Cheng-Zhu thinking favored by Qing social thought, emphasised patrilineal families and genealogy in society.[132]

The emperors and local officials exhorted families to compile genealogies in order to stabilize local society.[133] The genealogy was placed in the ancestral hall, which served as the lineage's headquarters and a place for annual ancestral sacrifice. A specific Chinese character appeared in the given name of each male of each generation, often well into the future. These lineages claimed to be based on biological descent but when a member of a lineage gained office or became wealthy, he might use considerable creativity in selecting a prestigious figure to be "founding ancestor".[134] Such worship was intended to ensure that the ancestors remain content and benevolent spirits (shen) who would keep watch over and protect the family. Later observers felt that the ancestral cult focused on the family and lineage, rather than on more public matters such as community and nation.[135]

Inner Mongols and Khalkha Mongols in the Qing rarely knew their ancestors beyond four generations and Mongol tribal society was not organized among patrilineal clans, contrary to what was commonly thought, but included unrelated people at the base unit of organization.[136] The Qing tried but failed to promote the Chinese Neo-Confucian ideology of organizing society along patrimonial clans among the Mongols.[137]

Manchu rulers presided over a multi-ethnic empire and the emperor, who was held responsible for "All Under Heaven" or Tian Xia, patronized and took responsibility for all religions and belief systems. The empire's "spiritual center of gravity" was the "religio-political state".[138] Since the empire was part of the order of the cosmos, which conferred the Mandate of Heaven, the Emperor as "Son of Heaven" was both the head of the political system and the head priest of the State Cult. The emperor and his officials, who were his personal representatives, took responsibility over all aspects of the empire, especially spiritual life and religious institutions and practices.[139] The county magistrate, as the emperor's political and spiritual representative, made offerings at officially recognized temples. The magistrate lectured on the Emperor's Sacred Edict to promote civic morality; he kept close watch over religious organizations whose actions might threaten the sovereignty and religious prerogative of the state.[140]

The Manchu imperial family were especially attracted by Yellow Sect or Gelug Buddhism that had spread from Tibet into Mongolia. The Fifth Dalai Lama, who had gained power in 1642, just before the Manchus took Beijing, looked to the Qing court for support. The Kangxi and Qianlong emperors practiced this form of Tibetan Buddhism as one of their household religions and built temples that made Beijing one of its centers, and constructed a replica Lhasa's Potala Palace at their summer retreat in Rehe.[141]

Shamanism, the most common religion among Manchus, was a spiritual inheritance from their Tungusic ancestors that set them off from Han Chinese.[142] State shamanism was important to the imperial family both to maintain their Manchu cultural identity and to promote their imperial legitimacy among tribes in the northeast.[143] Imperial obligations included rituals on the first day of Chinese New Year at a shamanic shrine (tangse).[144] Practices in Manchu families included sacrifices to the ancestors, and the use of shamans, often women, who went into a trance to seek healing or exorcism.[145]

The belief system most widely practiced among Han Chinese is often called local, popular, or folk religion, and was centered around the patriarchal family, the maintenance of the male family line, and shen, or spirits. Common practices included ancestor veneration, filial piety, local gods and spirits. Rites included mourning, funeral, burial, practices.[146] Since they did not require exclusive allegiance, forms and branches of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism were intertwined, for instance in the syncretic Three teachings.[147] Chinese folk religion combined elements of the three, with local variations.[148] County magistrates, who were graded and promoted on their ability to maintain local order, tolerated local sects and even patronized local temples as long as they were orderly, but were suspicious of heterodox sects that defied state authority and rejected imperial doctrines. Some of these sects indeed had long histories of rebellion, such as the Way of Former Heaven, which drew on Daoism, and the White Lotus society, which drew on millennial Buddhism. The White Lotus Rebellion (1796–1804) confirmed official suspicions as did the Taiping Rebellion, which drew on millennial Christianity.

The Abrahamic religions had arrived from Western Asia as early as the Tang dynasty but their insistence that they should be practiced to the exclusion of other religions made them less adaptable than Buddhism, which had quickly been accepted as native. Islam predominated in Central Asian areas of the empire, while Judaism and Christianity were practiced in well-established but self-contained communities.[149]

Several hundred Catholic missionaries arrived from the late Ming period until the proscription of Christianity in 1724. The Jesuits adapted to Chinese expectations, evangelized from the top down, adopted the robes and lifestyles of literati, becoming proficient in the Confucian classics, and did not challenge Chinese moral values. They proved their value to the early Manchu emperors with their work in gunnery, cartography, and astronomy, but fell out of favor for a time until the Kangxi Emperor's 1692 edict of toleration.[150] In the countryside, the newly arrived Dominican and Franciscan clerics established rural communities that adapted to local folk religious practices by emphasizing healing, festivals, and holy days rather than sacraments and doctrine. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, a spectrum of Christian believers had established communities.[151] In 1724, the Yongzheng Emperor (1678–1735) announced that Christianity was a "heterodox teaching" and hence proscribed.[152] Since the European Catholic missionaries kept control in their own hands and had not allowed the creation of a native clergy, however, the number of Catholics would grow more rapidly after 1724 and local communities could set their own rules and standards. In 1811, Christian religious activities were further criminalized by the Jiaqing Emperor (1760–1820).[153] The imperial ban was lifted by Treaty in 1846.[154]

The first Protestant missionary to China was Robert Morrison (1782–1834) of the London Missionary Society (LMS),[155] who arrived at Canton on September 6, 1807. He completed a translation of the entire Bible in 1819.[156] Liang Afa (1789–1855), a Morrison-trained Chinese convert, branched out the evangelization mission in inner China.[157][158] The two Opium Wars (1839–1860) marked the watershed of Protestant Christian missions.[152] The 1842 Treaty of Nanjing,[159] the American treaty and the French treaty signed in 1844,[160] and the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin,[152] distinguished Christianity from the local religions and granted it protected status.[161] Chinese popular cults, such as the White Lotus and the Eight Trigram, presented themselves as Christian to share this protection.[162]

In the late 1840s Hong Xiuquan read Morrison's Chinese Bible, as well as Liang Afa's evangelistic pamphlet, and announced to his followers that Christianity in fact had been the religion of ancient China before Confucius and his followers drove it out.[163] He formed the Taiping Movement, which emerged in South China as a "collusion of the Chinese tradition of millenarian rebellion and Christian messianism", "apocalyptic revolution, Christianity, and 'communist utopianism'".[164]

After 1860, enforcement of the treaties allowed missionaries to spread their evangelization efforts outside Treaty Ports. Their presence created cultural and political opposition. Historian John K. Fairbank observed that "[t]o the scholar-gentry, Christian missionaries were foreign subversives, whose immoral conduct and teaching were backed by gunboats".[165] In the next decades, there were some 800 conflicts between village Christians and non-Christians (jiao'an) mostly about non-religious issues, such as land rights or local taxes, but religious conflict often behind such cases.[166] In the summer of 1900, as foreign powers contemplated the division of China, village youths, known as Boxers, who practiced Chinese martial arts and spiritual practices, reacted against Western power and churches, attacked and murdered Chinese Christians and foreign missionaries in the Boxer Uprising. The imperialist powers once again invaded and imposed a substantial indemnity. The Beijing government reacted by implementing substantial fiscal and administrative reforms but this defeat convinced many among the educated elites that popular religion was an obstacle to China's development as a modern nation, and some turned to Christianity as a spiritual tool to build one.[167]

By 1900, there were about 1,400 Catholic priests and nuns in China serving nearly 1 million Catholics. Over 3,000 Protestant missionaries were active among the 250,000 Protestant Christians in China.[168] Western medical missionaries established clinics and hospitals, and led medical training in China.[169] Missionaries began establishing nurse training schools in the late 1880s, but nursing of sick men by women was rejected by local tradition, so the number of students was small until the 1930s.[170]

By the end of the 17th century, the Chinese economy had recovered from the devastation caused by the wars in which the Ming dynasty were overthrown.[171] In the following century, markets continued to expand, but with more trade between regions, a greater dependence on overseas markets and a greatly increased population.[172] By the end of the 18th century the population had risen to 300 million from approximately 150 million during the late Ming dynasty. The dramatic rise in population was due to several reasons, including the long period of peace and stability in the 18th century and the import of new crops China received from the Americas, including peanuts, sweet potatoes and maize. New species of rice from Southeast Asia led to a huge increase in production. Merchant guilds proliferated in all of the growing Chinese cities and often acquired great social and even political influence. Rich merchants with official connections built up huge fortunes and patronized literature, theater and the arts. Textile and handicraft production boomed.[173]

The government broadened land ownership by returning land that had been sold to large landowners in the late Ming period by families unable to pay the land tax.[174] To give people more incentives to participate in the market, they reduced the tax burden in comparison with the late Ming, and replaced the corvée system with a head tax used to hire laborers.[175] The administration of the Grand Canal was made more efficient, and transport opened to private merchants.[176] A system of monitoring grain prices eliminated severe shortages, and enabled the price of rice to rise slowly and smoothly through the 18th century.[177] Wary of the power of wealthy merchants, Qing rulers limited their trading licenses and usually refused them permission to open new mines, except in poor areas.[178] These restrictions on domestic resource exploration, as well as on foreign trade, are critiqued by some scholars as a cause of the Great Divergence, by which the Western world overtook China economically.[179][180]

During the Ming–Qing period (1368–1911) the biggest development in the Chinese economy was its transition from a command to a market economy, the latter becoming increasingly more pervasive throughout the Qing's rule.[135] From roughly 1550 to 1800 China proper experienced a second commercial revolution, developing naturally from the first commercial revolution of the Song period which saw the emergence of long-distance inter-regional trade of luxury goods. During the second commercial revolution, for the first time, a large percentage of farming households began producing crops for sale in the local and national markets rather than for their own consumption or barter in the traditional economy. Surplus crops were placed onto the national market for sale, integrating farmers into the commercial economy from the ground up. This naturally led to regions specializing in certain cash-crops for export as China's economy became increasingly reliant on inter-regional trade of bulk staple goods such as cotton, grain, beans, vegetable oils, forest products, animal products, and fertilizer.[127]

Silver entered in large quantities from mines in the New World after the Spanish conquered the Philippines in the 1570s. The re-opening of the southeast coast, which had been closed in the late 17th century, quickly revived trade, which expanded at 4% per annum throughout the latter part of the 18th century.[181] China continued to export tea, silk and manufactures, creating a large, favorable trade balance with the West.[173] The resulting expansion of the money supply supported competitive and stable markets.[182] During the mid-Ming China had gradually shifted to silver as the standard currency for large scale transactions and by the late Kangxi reign the assessment and collection of the land tax was done in silver. Landlords began only accepting rent payments in silver rather than in crops themselves, which in turn incentivized farmers to produce crops for sale in local and national markets rather than for their own personal consumption or barter.[127] Unlike the copper coins, qian or cash, used mainly for smaller transactions, silver was not reliably minted into a coin but rather was traded in units of weight: the liang or tael, which equaled roughly 1.3 ounces of silver. A third-party had to be brought in to assess the weight and purity of the silver, resulting in an extra "meltage fee" added on to the price of transaction. Furthermore, since the "meltage fee" was unregulated it was the source of corruption. The Yongzheng emperor cracked down on the corrupt "meltage fees", legalizing and regulating them so that they could be collected as a tax. From this newly increased public coffer, the Yongzheng emperor increased the salaries of the officials who collected them, further legitimizing silver as the standard currency of the Qing economy.[135]

The second commercial revolution also had a profound effect on the dispersion of the Qing populace. Up until the late Ming there existed a stark contrast between the rural countryside and cities because extraction of surplus crops from the countryside was traditionally done by the state. However, as commercialization expanded in the late-Ming and early-Qing, mid-sized cities began popping up to direct the flow of domestic, commercial trade. Some towns of this nature had such a large volume of trade and merchants flowing through them that they developed into full-fledged market-towns. Some of these more active market-towns even developed into small cities and became home to the new rising merchant class.[127] The proliferation of these mid-sized cities was only made possible by advancements in long-distance transportation and communication. As more and more Chinese citizens were travelling the country conducting trade they increasingly found themselves in a far-away place needing a place to stay; in response the market saw the expansion of guild halls to house these merchants.[135]

Full-fledged trade guilds emerged, which, among other things, issued regulatory codes and price schedules, and provided a place for travelling merchants to stay and conduct their business. Along with the huiguan trade guilds, guild halls dedicated to more specific professions, gongsuo, began to appear and to control commercial craft or artisanal industries such as carpentry, weaving, banking, and medicine.[135] By the nineteenth century guild halls worked to transform urban areas into cosmopolitan, multi-cultural hubs, staged theatre performances open to general public, developed real estate by pooling funds together in the style of a trust, and some even facilitated the development of social services such as maintaining streets, water supply, and sewage facilities.[127]