The architecture of the United States demonstrates a broad variety of architectural styles and built forms over the country's history of over two centuries of independence and former Spanish, French, Dutch and British rule.

Architecture in the United States has been shaped by many internal and external factors and regional distinctions. As a whole it represents a rich eclectic and innovative tradition.[1]

.jpg/440px-Cliff_Palace,_Mesa_Verde_Park,_Colorado,_US_(36).jpg)

The oldest surviving non-imported structures on the territory that is now known as the United States were made by the Ancient Pueblo People of the four corners region.[2] The Tiwa speaking people have inhabited Taos Pueblo continuously for over 1000 years.[3] Algonquian villages Pomeiooc and Section in what later became coastal North Carolina survive from the late 16th century. Artist and cartographer John White stayed at the short-lived Roanoke Colony for 13 months and recorded over 70 watercolor images of indigenous people, plants, and animals.

The remote location of the Hawaiian Islands from North America gave ancient Hawaii a substantial period of precolonial architecture. Early structures reflect Polynesian heritage and the refined culture of Hawaii. Post-contact late-19th-century Hawaiian architecture shows various foreign influences such as the Victorian, Georgian, and early-20th-century Spanish Colonial Revival styles.

When the Europeans settled in North America, they brought their architectural traditions and construction techniques for building. The oldest buildings in America have examples of that. Construction was dependent on the available resources. Wood and brick are the most common elements of English buildings in New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and the coastal South. It had also brought the conquest, destruction, and displacement of the indigenous peoples existing buildings in their homeland, as their dwelling and settlement construction techniques devalued compared to colonial standards. The colonizers appropriated the territories and sites for new forts, dwellings, missions, churches, and agricultural developments.

The Spanish colonial architecture in the United States was markedly different from the European styles adopted in other parts of America such as the simple French colonial houses in the Mississippi Valley, which were consisted of adjoining rooms that opened upon a galerie.[4] The Spanish architecture (particularly evident in ecclesiastical establishments) built in the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Florida, and Georgia was similar to the design adopted in Mexico.[4] According to scholars, the Spaniards built without any consideration to the cost, believing that their tenure in America would be eternal.[5]

Spanish colonial architecture was built in Florida and the Southeastern United States from 1559 to 1821. The conch style is represented in Pensacola, Florida and other areas of Florida, adorning houses with balconies of wrought iron, as appears in the mostly Spanish-built French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana. Fires in 1788 and 1794 destroyed the original French structures in New Orleans. Many of the city's present buildings date to late-18th-century rebuilding efforts.

The two earliest continuously occupied European settlements in the United States are St. Augustine, Florida founded in 1565 and Santa Fe, New Mexico. St. Augustine, the first continuously European-occupied city in North America, was established in 1565. Beginning in 1598, quarried coquina from Anastasia Island contributed to a new colonial style of architecture in this city. Coquina is a limestone conglomerate, containing small shells of mollusks. It was used in the construction of residential homes, the City Gate, the Cathedral Basilica, the Castillo de San Marcos, and Fort Matanzas. The city of St. Augustine is one of the rare vestiges of 17th-century Spanish colonial architecture in the present day United States.

Spanish exploration of the North American deserts, the present day Southwestern United States, began in the 1540s. The conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado crossed this region in search of the mythical cities of gold. Instead they found the ancient culture and architecture of the Pueblo people. The Pueblo people built dwellings of adobe, a sun-dried clay brick, with exposed wooden ceiling beams. Their cubic form and dense arrangement gave villages a singular aspect. The modest unadorned structures remained constant and cool. The Spanish conquered these pueblos and made Pueblo de Santa Fe the administrative capital of the Santa Fe de Nuevo México Province in 1609. The Palace of the Governors was built between 1610 and 1614, mixing Pueblo Indian and Spanish influences. The building is long and has a patio. The Mission San Francisco de Asis in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico dates from the 1770s and used the adobe technique as well, which gave the edifice a striking look of bold austerity. Centuries later the Pueblo Revival Style architecture style developed in the region. The Mission San Xavier del Bac near Tucson, Arizona, has Churrigueresque detailing from southern examples in New Spain. Its facade is framed by two massive towers and the entrance is flanked by estipites.

In the late 18th century, the Spanish founded a series of presidios (forts) in the upper Las Californias Province to resist Russian and British colonization there, the Presidio of San Diego, Presidio of Santa Barbara, Presidio of Monterey, and Presidio of San Francisco were established to do this and support the occupation by new missions and settlements. From 1769 to 1823, the Franciscans created a linear network of twenty-one Missions in California. The missions had a significant influence on later regional architecture. An example of a period residence is the Casa de la Guerra, in Santa Barbara.

Developed from around 1630 with the arrival of Dutch colonists to New Amsterdam and the Hudson River Valley in what is now New York[6] and in Bergen in what is now New Jersey.[7][8] Initially the settlers built small, one room cottages with stone walls and steep roofs to allow a second floor loft. By 1670 or so, two-story gable-end homes were common in New Amsterdam.

French Colonial developed in the settlements of the Illinois Country and French Louisiana. It is believed to have been primarily influenced by the building styles of French Canada and the Caribbean.[9] It had its beginnings in 1699 with the establishment of French Louisiana but continued to be built after Spain assumed control of the colonial territory in 1763. Styles of building that evolved during the French colonial period include the Creole cottage, Creole townhouse, and French Creole plantation house.[10]

Excavations at the first permanent English-speaking settlement, Jamestown, Virginia (founded 1607) have unearthed part of the triangular James Fort and numerous artifacts from the early 17th century. Nearby Williamsburg was Virginia's colonial capital and is now a tourist attraction as a well-preserved 18th-century town.

The New World population of 200,000 in 1657, ninety percent of whom drew from England, used the same simple construction techniques as those in their respective mother countries.[11] These settlers often came to the New World for economic purposes, therefore revealing why most early homes reflect the influences of modest village homes and small farms. The appearance of structures was very plain and made with little imported material. Windows, for example, were extremely small. The size did not increase until long after the British were manufacturing glass. This was because the Venetians had not rediscovered the strictly Roman clear glass until the 15th century and it did not come to England until another hundred years later.[12] The few windows that did exist on early colonial homes had small panes held together by a lead framework, much like a typical church's stained glass window. The glass that was used was imported from England and was incredibly expensive.[13] In the 18th century, many of these houses were restored and sash windows replaced the originals. These were invented by Robert Hooke (1635–1703) and were made so that one panel of glass easily slid up, vertically, behind another.[14]

Timber, especially white and red cedar, made for a great building resource and was readily abundant for the settlers in the English colonies, so naturally many houses were made of wood.[15] As for decorative elements, as said before most colonial houses were built plainly and therefore most colonial house designs led to a very simple outcome. Although one subtle element of ornamentation that was used on the front door. The owner would take nails, think of an object or pattern to make with them, and nail that decoration onto the door. The more nails one had, the more extravagant and elaborate the pattern could become.[16]

The most prized architectural aspect of the house was the chimney. Large and usually made of brick or stone, the chimney was very fashionable at this time, specifically 1600–1715. During the Tudor period in England, which lasted up until around 1603, coal became the popular material for heating the home. Before that, a wood fire was burned on the floor in the center of the house, with the smoke escaping only through windows and vents. With coal, this method could not suffice because the smoke was unacceptably black and sticky. It needed to be contained and the function of a chimney was to do just that.[13]

The oldest remaining building of Plymouth, Massachusetts is the Harlow Old Fort House built 1677 and now a museum. The Fairbanks House (ca. 1636) in Dedham, Massachusetts is the oldest remaining wood-frame house in North America. Several notable colonial era buildings remain in Boston. Boston's Old North Church, built 1723 in the style of Sir Christopher Wren, became an influential model for later United States church design.

The Georgian style appeared during the 18th century, and Palladian architecture took hold of colonial Williamsburg in the Colony of Virginia. The Governor's Palace there, built in 1706–1720, had a vast gabled entrance at the front. It respects the principle of symmetry and uses the materials that were found in the Tidewater region of the Mid-Atlantic colonies: red brick, white painted wood, and blue slate used for the roof with a double slant. This style is used to build the houses for prosperous plantation owners in the country and wealthy merchants in town.

In religious architecture, the common design features were brick, stone-like stucco, and a single spire that tops the entrance. They can be seen in Saint Paul's Church (1761) in Mount Vernon, New York or Saint Paul's Chapel (1766) in New York, New York. The architects of this period were more influenced by the canons of Old World architecture. Peter Harrison (1716–1755) used his European techniques in designing the Redwood Library and Athenaeum (1748 and 1761), in Newport, Rhode Island and now the oldest community library still occupying its original building in the United States. Boston and Salem in the Massachusetts Bay Colony were two primary cities where the Georgian style took hold, but in a simpler style than in England, adapted to the colonial limitations.

In 1776 the members of the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence of the Thirteen Colonies. After the long and distressing American Revolutionary War, the 1783 Treaty of Paris recognized the existence of the new republic, the United States of America. Even though it was a firm break with the English politically, the Georgian influences continued to mark the buildings constructed. Public and commercial needs grew in parallel with the territorial extension. The buildings of these new federal and business institutions used the classic vocabulary of columns, domes and pediments, in reference to ancient Rome and Greece, which symbolize the democracy of the newfound nation. Architectural publications multiplied: in 1797, Asher Benjamin published The Country Builder's Assistant. Americans looked to affirm their independence in the domains of politics, economics, and culture with new civic architecture for government, religion, and education.

In the 1780s the Federal style of architecture began to diverge bit-by-bit from the Georgian style and became a uniquely American genre. At the time of the War of Independence, houses stretched out along a strictly rectangular plan, adopting curved lines and favoring decorative details such as garlands and urns. Certain openings were ellipsoidal in form, one or several pieces were oval or circular.

The Bostonian architect Charles Bulfinch fitted the Massachusetts State House' in 1795–1798 with an original gilded dome. He worked on the construction of several houses in Louisburg Square of the Beacon Hill quarter in Boston. Samuel McIntire designed the John Gardiner-Pingree house (1805) in Salem, Massachusetts with a gentle sloped roof and brick balustrade. With Palladio as inspiration, he linked the buildings with a semi-circular column supported portico.

The Federal style of architecture was popular along the Atlantic coast from 1780 to 1830. Characteristics of this style include neoclassical elements, bright interiors with large windows and white walls and ceilings, and a decorative yet restrained appearance that emphasized rational elements. Significant federal style architects at the time include: Asher Benjamin, Charles Bulfinch, Samuel McIntire, Alexander Parris, and William Thornton.

Thomas Jefferson, who was the third president of the United States between 1801 and 1809, was a scholar in many domains, including architecture. Having journeyed several times in Europe, he hoped to apply the formal rules of palladianism and of antiquity in public and private architecture and master planning. He contributed to the plans for the University of Virginia, which began construction in 1817. The project was completed by Benjamin Latrobe applying Jefferson's architectural concepts. The university library is situated under a The Rotunda covered by a dome inspired by the Pantheon of Rome. The combination created a uniformity thanks to the use of brick and wood painted white. For the new Virginia State Capitol building (1785–1796) in Richmond, Virginia, Jefferson was inspired by the ancient Rome Maison Carrée in Nîmes, but chose the Ionic order for its columns. A man of the Age of Enlightenment, Thomas Jefferson had participated in the emancipation of New World architecture by expressing his vision of an art-form in service of democracy. He contributed to developing the Federal style in his country by combining European Neoclassical architecture and American democracy.

Thomas Jefferson also designed the buildings for his plantation Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia. Monticello is a tribute to the Neo Palladian style, modeled on the Hôtel de Salm in Paris, that Jefferson saw while the ambassador to France. Work on Monticello commenced in 1768 and modifications continued until 1809. This American variation on Palladian architecture borrowed from British and Irish models and revived the tetrastyle portico with Doric columns. This interest in Roman elements appealed in a political climate that looked to the ancient Roman Republic as a model

The United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., is an example of uniform urbanism: the design of the capitol building was imagined by the French Pierre Charles L'Enfant. This ideal of the monumental city and neoclassicism. Several cities wanted to apply this concept, which is part of the reason why Washington, D.C., did. The new nation's capital should have the best examples of architecture at the time.

The White House was constructed after the creation of Washington, D.C., by congressional law in December 1790. After a contest, James Hoban, an Irish American, was chosen and the construction began in October 1792. The building that he had conceived was modeled upon the first and second floors of the Leinster House, a ducal palace in Dublin, Ireland which is now the seat of the Irish Parliament. But during the War of 1812, a large part of the city was burned, and the White House was ravaged. Only the exterior walls remained standing, but it was reconstructed. The walls were painted white to hide the damage caused by the fire. At the beginning of the 20th century, two new wings were added to support the development of the government.

The United States Capitol was constructed in successive stages starting in 1792. Shortly after the completion of its construction, it was partially burned by the British during the War of 1812. Its reconstruction began in 1815 and did not end until 1830. During the 1850s, the building was greatly expanded by Thomas U. Walter. In 1863, the imposing Statue of Freedom, was placed on the top of the current (new at the time) dome.

The Washington Monument is an Obelisk erected in honor of George Washington, the first American president. It was Robert Mills who had designed it originally in 1838. There is a perceivable color difference towards the bottom of the monument, which is because its construction was put on hiatus for lack of money. At 555.5 feet (169.3 m) high, it was completed in 1884 and opened to the public in 1888.

Much architecture of the Deep South was developed in the context of the plantation economy. Plantation complexes in the Southern United States often featured European-derived styles for the slaveowners' houses, while housing for enslaved African Americans often drew upon vernacular building traditions.[17]

Anglophone plantation owners often favored the Greek Revival style, featuring a neoclassical pediment with columns, as at Belle Meade Plantation in Tennessee, with a symmetrical columned porch and narrow windows.[18] The domestic architecture in the South adapted the neoclassical model by supporting a mid-height balcony on the front without a pediment or entrance portico, such as at Oak Alley Plantation, in St. James Parish, Louisiana.[19] These houses adapted to the regional climate and into the economy of a plantation with enslaved labor for construction.

In regions that had experienced French and Spanish colonization, such as the Gulf Coast, buildings were often constructed in Creole architectural styles.[20]

The Homestead Act of 1862 brought property ownership within reach for millions of citizens, displaced native peoples, and changed the character of settlement patterns across the Great Plains and Southwest. The law offered a modest farm free of charge to any adult male who cultivated the land for five years and built a residence on the property. This established a rural pattern of isolated farmsteads in the Midwest and West instead of the European and eastern U.S. states' villages and towns. Settlers built homes from local materials, such as rustic sod, semi-cut stone, mortared cobble, adobe bricks, and rough logs. They erected log cabins in forested areas and sod houses, such as the Sod House (Cleo Springs, Oklahoma), in treeless prairies. The present-day sustainable architecture method of Straw-bale construction was pioneered in late-19th-century Nebraska with baling machines.

The Spanish and later Mexican Alta California Ranchos and early American pioneers used the readily available clay to make adobe bricks, and distant forests' tree trunks for beams sparingly. Locally made roof tiles were produced by the Mission Indians. As milled wood became more available in the mid-19th century the Monterey Colonial architecture style first developed in Monterey and then spread. The Leonis Adobe, Larkin House, and Rancho Petaluma Adobe are original examples.

Greek revival style attracted American architects working in the first half of the 19th century. The young nation, free from Britannic protection, was persuaded to be the new Athens, that is to say, a foyer for democracy.

Benjamin Latrobe (1764–1820) and his students William Strickland (1788–1854) and Robert Mills (1781–1855) obtained commissions to build some banks and churches in the big cities (Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, DC).

Some state capitol buildings adopted the Greek Revival style such as in North Carolina (Capitol building in Raleigh, rebuilt in 1833–1840 after a fire) or in Indiana (Capitol building in Indianapolis). One later example of these is the Ohio State Capitol in Columbus, designed by Henry Walters and completed in 1861. The simple façade, continuous cornice and the absence of a dome give the impression of the austerity and greatness of the building. It has a very symmetrical design and houses the Supreme Court and a library. A rare style also was adopted around this time, Egyptian Revival architecture.

From the 1840s on, the Gothic Revival style became popular in the United States, under the influence of Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852). He defined himself in a reactionary context to classicism and development of romanticism. His work is characterized by a return to Medieval decor: chimneys, gables, embrasure towers, warhead windows, gargoyles, stained glass and severely sloped roofs. The buildings adopted a complex design that drew inspiration from symmetry and neoclassicism.

The great families of the east coast had immense estates and villas constructed in the style, with antipodes of Neoclassicism. Some took Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill House as a model. Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892) worked on villa projects in the Hudson River Valley and used details from the Gothic to Baroque repertoire. For the Jay Gould estate country house "Lyndhurst" in Tarrytown, New York, Alexander Jackson Davis designed a building with a complex asymmetrical outline, and opened the double-height art gallery with stained glass windows.

New York City is home to James Renwick Jr's Saint Patrick Cathedral, an elegant synthesis of the Notre Dame Cathedral in Reims and the Cologne Cathedral. The project was entrusted to him in 1858 but completed by the erection of two spires on the facade in 1888. The use of materials lighter than stone allowed to pass from flying buttresses to exterior buttresses. Renwick also showed his talent in Washington, D.C., with the construction of the Smithsonian Institution. But his critics reproached him for having broken the architectural harmony of the capital by building an eccentric combination in red brick using Byzantine, Romanesque, Lombard, and eclectic themes.

Richard Upjohn (1802–1878) specialized in the rural churches of the northeast, but his major work is still "Trinity Church" in New York. His red sandstone architecture makes reference to the 16th-century forms in Europe. The Gothic Revival style was also used in the construction of universities (Yale, Harvard) and churches. The success of the Gothic Revival was prolonged up until the beginning of the 20th century in numerous Skyscrapers, notably in Chicago and in New York.

Following the American Civil War and through the turn of the 20th century, a number of related styles, trends, and movements emerged, are loosely and broadly categorized as "Victorian," due to their correspondence with similar movements of the time in the British Empire during the later reign of Queen Victoria. Many architects working during this period would cross various modes, depending on the commission. Key influential American architects of the period include Richard Morris Hunt, Frank Furness, and Henry Hobson Richardson.

After the war, the uniquely American Stick Style developed as a form of construction that uses wooden rod trusswork, the origin of its name. The style was commonly used in houses, hotels, railway depots, and other structures primarily of wood. The buildings are topped by high roofs with steep slopes and prominent decoration of the gables. The exterior is not bare of decoration, even though the main objective remains comfort. Richard Morris Hunt constructed John N. Griswold's house in Newport, Rhode Island in 1862 in this style. The "Stick Style" was progressively abandoned after c. 1873, gradually evolving into the Queen Anne Style.

On the west coast in California, Oregon, and Washington, domestic architecture evolved equally towards a more modern style. San Francisco has many representations of the Italianate, Stick-Eastlake, and Queen Anne styles of Victorian architecture, c. 1850s–1900. Constructed with Redwood lumber they resisted the 1906 San Francisco earthquake itself, though some burned in the aftermath. They introduced the contemporary services of central heating and electricity. The Carson Mansion conceived of by Builder-Architects, Samuel and Joseph Cather Newsom and built by an army of over 100 craftsman from the massive lumber operations of its owner, is prominently situated at the head of Old Town Eureka, California on Humboldt Bay. It is widely regarded as one of the highest executions of Queen Anne style in California and the United States.

On the east coast the Queen Anne evolved into the Shingle Style architecture. It is characterized by attention to a more relaxed rustic image. Richardson designed the William Watts Sherman House (1874–1875) in Newport, Rhode Island, and the Mary Fiske Stoughton House (1882–1883) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Charles Follen McKim the Newport Casino (1879–1881) using shingle clad asymmetrical facades.

While medieval influence rode high, in the second half of the 19th century, architects also responded to commissions for estate scale residences with Renaissance Revival residences. Industry and commerce tycoons invested in stone and commissioned mansions replicating European palaces. The Biltmore Estate near to Asheville, North Carolina is in the Châteauesque style of French Renaissance Revival, and is the largest private residence in the U.S. Richard Morris Hunt interpreted the Louis XII and François I wings from the Château de Blois for it.

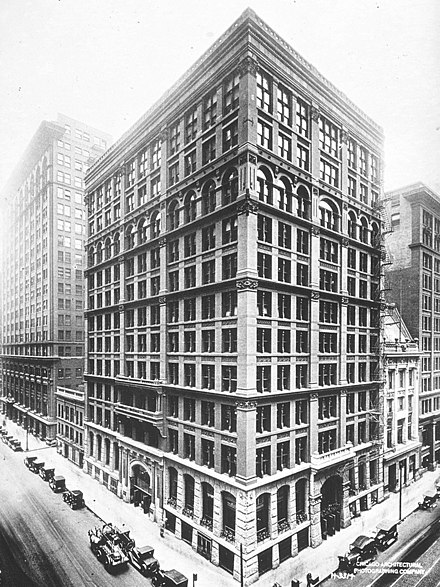

The most notable United States architectural innovation has been the skyscraper. Several technical advances made this possible. In 1853, Elisha Otis invented the first safety elevator which prevented a car from falling down the shaft if the suspending cable broke. Elevators allowed buildings to rise above the four or five stories that people were willing to climb by stairs for normal occupancy. An 1868 competition decided the design of New York City's six story Equitable Life Building, which would become the first commercial building to use an elevator. Construction commenced in 1873. Other structures followed such as the Auditorium Building, Chicago in 1885 by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan. This adopted Italian palazzo design details to give the appearance of a structured whole: for several decades American skyscrapers would blend conservative decorative elements with technical innovation.

Soon skyscrapers encountered a new technological challenge. Load-bearing stone walls become impractical as a structure gains height, reaching a technical limit at about 20 stories (culminating in the 1891 Monadnock Building by Burnham & Root in Chicago). Professional engineer William LeBaron Jenney solved the problem with a steel support frame in Chicago's 10-story Home Insurance Building, 1885. Arguably this is the first true skyscraper. The use of a thin curtain wall in place of a load-bearing wall reduced the building's overall weight by two thirds. Another feature that was to become familiar in 20th-century skyscrapers first appeared in Chicago's Reliance Building, designed by Charles B. Atwood and E.C. Shankland, Chicago, 1890–1895. Because outer walls no longer bore the weight of a building it was possible to increase window size. This became the first skyscraper to have plate glass windows take up a majority of its outer surface area.

Some of the most graceful early towers were designed by Louis Sullivan (1856–1924), America's first great modern architect. His most talented student was Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), who spent much of his career designing private residences with matching furniture and generous use of open space.

Daniel Burnham's "White City" of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, held in Chicago, Illinois, ceremonially marks the dawn of the golden age for the Beaux-Arts style, and larger firms such as McKim, Mead and White. The era is documented in photo architectural albums such as the Architectural photographic series of Albert Levy.[21]

The Columbian Exposition also reflected the rise of American landscape architecture and city planning. Notable were the works of Frederick Law Olmsted, an already-prominent and prolific landscape architect who had designed the Midway Plaisance of the 1893 Exhibition, having previously designed New York's Central Park in the 1850s, the layout of the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and many other works nationwide. Olmsted and his sons were also involved in the City Beautiful movement, which, as its name suggests, sought to aesthetically (and thus culturally) transform cities. The aspirations of the movement can be seen in the McMillan Plan for Washington, D.C.

As the century progressed, the Beaux-Arts influence would become somewhat more restrained, returning to its more Neoclassical roots. The Lincoln Memorial (1915–1922), made out of marble and white limestone, takes its form from doric order Greek temples without a pediment. Its architect, Henry Bacon, student of the ideas from the Beaux-Arts school, intended the 36 columns of monument to represent each of the 36 states in the Union at the time of Lincoln's death. The Jefferson Memorial was the last great monument constructed in the Beaux-Arts tradition, in the 1940s. Its architect, John Russell Pope, wanted to bring to light Jefferson's taste for Roman buildings. This is why he decided to imitate the Pantheon in Rome and grace the building with a similar type dome. It was severely criticized by the proponents of the International Style.

With the boom in the use of electric streetcars, the inner ring of suburbs developed around major cities, later to be aided by the advent of bicycles and automobiles. This boom in construction would result in a new, distinctly American form of house would emerge: the American Foursquare.

The trend of reviving previous styles continued over from the 19th century. Many of the revivals beginning in the late 19th century on into the 20th century would focus more on regional characteristics and earlier styles endemic to the United States and eclectically from abroad, further influenced by the rise of middle-class tourism.

The early 20th century saw Mediterranean Revival style architecture enter the large estate design vocabulary. A major and significant example is the Hearst Castle on the Central Coast of California, designed by architect Julia Morgan. The San Francisco Bay Area estate Filoli, by Willis Polk, is in Woodside, California with the mansion and gardens now part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and open to the public.

the Dumbarton Oaks estate, in Georgetown, Washington, D.C., has Italian Renaissance gardens by early landscape architect Beatrix Farrand and architectural design by several architects including Philip Johnson. The Harold Lloyd Estate, "Greenacres" in Beverly Hills, California, is a significant example from the 1920s, with extensive gardens by a leading estate Landscape designer in that era, A.E. Hanson.

.jpg/440px-SDSUHepnerHallPanJune2015_(cropped).jpg)

The 1915 Panama–California Exposition the architecture by Bertram Goodhue and Carleton Winslow Sr. intentionally moved beyond the Mission Revival Style, from their studying Spanish Colonial architecture and its Churrigueresque and Plateresque refinements in Mexico. The project was a popular success, and introduced the Spanish Colonial Revival style to many design professionals and the public in California and across the country.

George Washington Smith, based in Montecito and Santa Barbara, designed the detailed and integrated Andalusian Spanish Colonial Revival Casa del Herrero estate in 1926. Smith, Bertram Goodhue, Wallace Neff, and other notable architects created many 'Country Place Era' properties throughout California during this period. A civic example is the Santa Barbara County Courthouse and a commercial example the Mission Inn in Riverside, California.

The Georgian style predominated residential design in the British colonial era in the thirteen Colonies. At the Mount Pleasant mansion (1761–1762) in Philadelphia, the residence is constructed with an entrance topped by a pediment supported by Doric columns. The roof has a balustrade and a symmetrical arrangement, characteristic of the neoclassic style popular in Europe then.

In the early decades of the twentieth century when there was a growing nostalgia for its sense of order, the style was revived and adapted and in the United States came to be known as the Colonial Revival. From 1910–1930, the Colonial Revival movement was ascendant, with about 40% of U.S. homes built during this period in the Colonial Revival style.[22] In the immediate post-war period (c. 1950s–early 1960s), Colonial Revival homes continued to be constructed, but in simplified form. In the present-day, many New Traditional homes draw from Colonial Revival styles.[22]

.jpg/440px-Eldridge_Street_Synagogue_(42773).jpg)

One culturally significant early skyscraper was New York City's Woolworth Building designed by architect Cass Gilbert, 1913. Raising previous technological advances to new heights, 793 ft (233 m), it was the world's tallest building until 1930.[23] Frank Woolworth was fond of gothic cathedrals. Cass Gilbert constructed the office building as a cathedral of commerce and incorporated many Gothic revival decorative elements. The main entrance and lobby contain numerous allegories of thrift, including an acorn growing into an oak tree and a man losing his shirt. The popularity of the new Woolworth Building inspired many Gothic revival imitations among skyscrapers and remained a popular design theme until the art deco era. Other public concerns emerged following the building's introduction. New York City's 1916 Zoning Resolution setback law, which remained in effect until 1960, allowed structures to rise to any height as long as it reduced the area of each tower floor to one quarter of the structure's ground floor area.[24] The Woolworth Building represents this type of building referred to as "wedding cake" skyscrapers.[25]

Another significant event in skyscraper history was the competition for Chicago's Tribune Tower. Although the competition selected a gothic design influenced by the Woolworth building, some of the numerous competing entries became influential to other 20th-century architectural styles. Second-place finisher Eliel Saarinen submitted a modernist design. An entry from Walter Gropius brought attention to the Bauhaus school.

_--_2012_--_4.jpg/440px-Amboy_(California,_USA)_--_2012_--_4.jpg)

The automobile culture of the United States has spawned numerous forms of architectural expression peculiar to that country (or alongside Canada), often vernacular in origin, especially in Diners.

National Park Service rustic – sometimes colloquially called Parkitecture – is a style of architecture that developed in the early and middle 20th century in the United States National Park Service (NPS) through its efforts to create buildings that harmonized with the natural environment. Since its founding in 1916, the NPS sought to design and build visitor facilities without visually interrupting the natural or historic surroundings. The early results were characterized by intensive use of hand labor and a rejection of the regularity and symmetry of the industrial world, reflecting connections with the Arts and Crafts movement and American Picturesque architecture.

Morris Lapidus pioneered the "Miami Modern" style, best seen in the Ritz-Carlton South Beach, which went through a $90 million renovation in 2019.[26]

.jpg/440px-South_San_Jose_(crop).jpg)

The 1944 G. I. Bill of Rights was another federal government decision that changed the architectural landscape. Government-backed loans made home ownership affordable for many more citizens. Affordable automobiles, unprecedented federal and state investment in highways encouraging workers to live ever further from their workplace, corresponding with a decline in public transportation investment and popular preference for single family detached homes, led to the rise of suburbs. Simultaneously praised for their quality of life[citation needed] and condemned for architectural monotony, these have become a familiar feature of the United States landscape.

Interest in the simplification of the interior space and exterior facade progressed due to the work of Irving Gill, characterized by several Californian houses with flat roofs in the 1910s such as the Walter Luther Dodge house in Los Angeles. Rudolf M. Schindler and Richard Neutra adapted European modernism to the Californian context in the 1920s with the former's "Lovell Beach House" in Newport Beach and Schindler House in West Hollywood, and the latter's Lovell Health House in the Hollywood Hills.

European architects who emigrated to the United States before World War II launched what became a dominant movement in architecture, the International Style. The Lever House introduced a new approach to a uniform glazing of the skyscraper's skin, and located in Manhattan. An influential modernist immigrant architect was Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) and Walter Gropius (1883–1969), both former directors of Germany's famous design school, the Bauhaus.

The Reliance Building's move toward increased window area reached its logical conclusion in a New York City building with a Brazilian architect on land that is technically not a part of the United States. United Nations headquarters, 1949–1950, by Oscar Niemeyer has the first complete glass curtain wall.

American government buildings and skyscrapers of this period have are a style known as Federal Modernism. Based on pure geometric form, buildings in the International style have been both praised as minimalist monuments to American culture and corporate success by some, and criticized as sterile glass boxes by others.

Skyscraper hotels gained popularity with the construction of John Portman's (1924–) Westin Peachtree Plaza Hotel in Atlanta followed by his Renaissance Center in Detroit which remains the tallest skyscraper hotel in the Western Hemisphere.

In reaction to the "glass boxes" issue, some younger American architects such as Michael Graves (1945– ) have rejected the austere, boxy look in favor of postmodern buildings, such as those by Philip C. Johnson (1906–2005) with striking contours and bold decoration that alludes to historical styles of architecture.

The formal education and practice of U.S. architecture started in the early 19th century when Thomas Jefferson, and others, realized a need for trained architects to fulfill an acute need for professionals to support an expanding nation. It was then that architectural education became institutionalized within a formal setting; prior to this, the dominant model for training was apprenticeship to artisan, "at best a hit-or miss proposition educationally."[27] Additionally, most who called themselves architects during that general time period, were male, well-off, white, and trained in the French Ecole des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) education philosophy. According to Georg Hegel, a fine art philosophy, by definition, that focused on aesthetics and intellectual purpose, rather than any practical function.[28]

This is the basis in which Thomas Jefferson, and others, formalized U.S. architectural pedagogy 150 years ago. According to Ernest Boyer and Lee Mitgang, a philosophy that advocated for:

This philosophy does not mention scientific or social science research. This legacy has meant that today, fewer than 20% of the 115 accredited Schools of Architecture offer a Ph.D. program; in addition, only a handful more offer exposure to and experience in rigorous research within building science & technology centers and laboratory settings. According to Gordon Chong, the architectural profession having emphasized "looking back as a means for justifying design decisions for future design," there remains a significant imbalance in learning between experience, intuition, and evidence-based design.[31]

There are currently over 83,000 members of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) estimates the number of architects licensed in the United States at 105,847. Architecture firms employ approximately 158,000 people in the United States (Bureau of Labor Statistics).[32]

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 33 professions are identified as over 90% white, including architecture at 91.3% white.[33] A number of allied professions are also over 90% white, including construction managers (91.8%), construction supervisors (91.8%), and cost estimators (93.9%), and related construction tradespersons including electricians (90.0%), painters (90.7%), carpenters (90.9%), cement masons (91.2%), steel workers (92.3%), and sheet metal workers (93.5%). The US labor force is 80% white.[34]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)