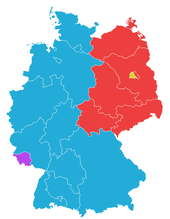

Восточная Германия ( ‹См. Tfd› на немецком языке : Ostdeutschland , произносится [ˈɔstˌdɔʏtʃlant] ), официально известная какГерманская Демократическая Республика(ГДР;Deutsche Demokratische Republik,произносится[ˈdɔʏtʃədemoˈkʁaːtɪʃəʁepuˈbliːk] ,ГДР), была страной вЦентральной Европес моментаее образования7 октября 1949 года доее воссоединениясЗападной Германией3 октября 1990 года. До 1989 года она в целом рассматривалась каккоммунистическое государствои описывала себя каксоциалистическое«государство рабочих и крестьян».[5]Экономикастраныбылацентрализованно планируемойипринадлежала государству.[6]Хотя ГДР пришлось выплатить Советскому Союзу значительные военные репарации, ее экономика стала самой успешной вВосточном блоке.[7]

До своего создания территория страны управлялась и оккупировалась советскими войсками после Берлинской декларации, отменившей суверенитет Германии во Второй мировой войне . Потсдамское соглашение установило зону советской оккупации , ограниченную на востоке линией Одер-Нейсе . В ГДР доминировала Социалистическая единая партия Германии (СЕПГ), коммунистическая партия , прежде чем она была демократизирована и либерализована в 1989 году в результате давления на коммунистические правительства, вызванного революциями 1989 года . Это проложило путь к воссоединению Восточной Германии с Западной. В отличие от правительства Западной Германии, СЕПГ не рассматривала свое государство как преемника Германского рейха (1871–1945) и отменила цель объединения в конституции ( 1974 ). Управляемая СЕПГ ГДР часто описывалась как советское государство-сателлит ; историки описывали ее как авторитарный режим. [8] [9]

Географически ГДР граничила с Балтийским морем на севере, с Польшей на востоке, с Чехословакией на юго-востоке и с Западной Германией на юго-западе и западе. Внутри ГДР также граничила с советским сектором оккупированного союзниками Берлина , известным как Восточный Берлин , который также управлялся как фактическая столица страны . Она также граничила с тремя секторами, оккупированными Соединенными Штатами , Соединенным Королевством и Францией, известными под общим названием Западный Берлин ( фактическая часть ФРГ). Эмиграция на Запад была значительной проблемой, поскольку многие эмигранты были хорошо образованными молодыми людьми; такая эмиграция ослабляла государство экономически. В ответ правительство ГДР укрепило свою внутреннюю границу с Германией и позже построило Берлинскую стену в 1961 году . [10] Многие люди, пытавшиеся бежать [11] [12] [13], были убиты пограничниками или минами-ловушками, такими как наземные мины . [14]

В 1989 году многочисленные социальные, экономические и политические силы в ГДР и за рубежом, одним из самых заметных из которых были мирные протесты, начавшиеся в городе Лейпциг , привели к падению Берлинской стены и созданию правительства, приверженного либерализации. В следующем году в стране прошли свободные и справедливые выборы , [15] и начались международные переговоры между четырьмя бывшими странами-союзниками и двумя немецкими государствами. Переговоры привели к подписанию Договора об окончательном урегулировании , который заменил Потсдамское соглашение о статусе и границах будущей, объединенной Германии. ГДР прекратила свое существование, когда ее пять земель («Länder») присоединились к Федеративной Республике Германии в соответствии со статьей 23 Основного закона , а ее столица Восточный Берлин объединилась с Западным Берлином 3 октября 1990 года. Несколько лидеров ГДР, в частности ее последний коммунистический лидер Эгон Кренц , позже были привлечены к ответственности за преступления, совершенные в эпоху ГДР. [16] [17]

Официальное название было Deutsche Demokratische Republik (Германская Демократическая Республика), обычно сокращаемое до DDR (ГДР). Оба термина использовались в Восточной Германии, с увеличением использования сокращенной формы, особенно с тех пор, как Восточная Германия считала западных немцев и западных берлинцев иностранцами после обнародования своей второй конституции в 1968 году. Западные немцы, западные СМИ и государственные деятели изначально избегали официального названия и его сокращения, вместо этого используя такие термины, как Ostzone (Восточная зона), [18] Sowjetische Besatzungszone (Советская оккупационная зона; часто сокращаемая до SBZ ) и sogenannte DDR [19] или «так называемая ГДР». [20]

Центр политической власти в Восточном Берлине на Западе назывался Панков (место командования советскими войсками в Германии находилось в Карлсхорсте , районе на востоке Берлина). [18] Однако со временем аббревиатура «ГДР» также стала все чаще использоваться в разговорной речи западными немцами и западногерманскими СМИ. [i]

Термин Westdeutschland ( Западная Германия ) , используемый западными немцами, почти всегда относился к географическому региону Западной Германии , а не к территории в пределах границ Федеративной Республики Германии. Однако это использование не всегда было последовательным, и жители Западного Берлина часто использовали термин Westdeutschland для обозначения Федеративной Республики. [21] До Второй мировой войны термин Ostdeutschland (Восточная Германия) использовался для описания всех территорий к востоку от Эльбы ( Восточная Эльбия ), что отражено в работах социолога Макса Вебера и политического теоретика Карла Шмитта . [22] [23] [24] [25] [26]

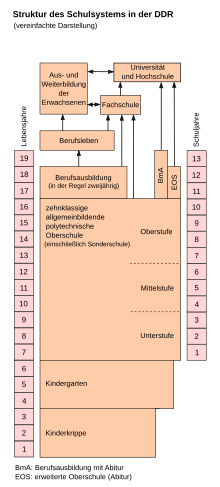

Объясняя внутреннее влияние правительства ГДР с точки зрения немецкой истории в долгосрочной перспективе, историк Герхард А. Риттер (2002) утверждал, что восточногерманское государство определялось двумя доминирующими силами — советским коммунизмом , с одной стороны, и немецкими традициями, профильтрованными через межвоенный опыт немецких коммунистов, с другой. [27] На протяжении всего своего существования ГДР последовательно боролась с влиянием более процветающего Запада, с которым восточные немцы постоянно сравнивали свою собственную нацию. Заметные преобразования, инициированные коммунистическим режимом, были особенно очевидны в отмене капитализма, капитальном ремонте промышленного и сельскохозяйственного секторов, милитаризации общества и политической ориентации как системы образования , так и средств массовой информации.

С другой стороны, новый режим внес относительно немного изменений в исторически независимые области науки, инженерные профессии, [28] : 185–189 протестантские церкви, [28] : 190 и во многие буржуазные образы жизни. [28] : 190 Социальная политика, говорит Риттер, стала важнейшим инструментом легитимации в последние десятилетия и смешала социалистические и традиционные элементы примерно в равной степени. [28]

На Ялтинской конференции во время Второй мировой войны союзники , то есть Соединенные Штаты (США), Соединенное Королевство (Великобритания) и Советский Союз (СССР), договорились о разделе побежденной нацистской Германии на зоны оккупации , [29] а также о разделе Берлина, столицы Германии, между союзными державами. Первоначально это означало формирование трех зон оккупации, то есть американской, британской и советской. Позже из зон США и Великобритании была выделена французская зона. [30]

Правящая коммунистическая партия, известная как Социалистическая единая партия Германии (СЕПГ), была образована 21 апреля 1946 года в результате слияния Коммунистической партии Германии (КПГ) и Социал-демократической партии Германии (СДПГ). [31] Две бывшие партии были известными соперниками, когда они были активны до того, как нацисты консолидировали всю власть и криминализировали их, и официальная восточногерманская и советская история изображала это слияние как добровольное объединение усилий социалистических партий и символ новой дружбы немецких социалистов после победы над их общим врагом; однако есть много свидетельств того, что слияние было более проблемным, чем обычно изображают, и что советские оккупационные власти оказали большое давление на восточное отделение СДПГ, чтобы оно слилось с КПГ, а коммунисты, имевшие большинство, фактически полностью контролировали политику. [32] СЕПГ оставалась правящей партией на протяжении всего периода существования восточногерманского государства. У нее были тесные связи с Советским Союзом, который сохранял свои военные силы в Восточной Германии вплоть до распада советского режима в 1991 году ( Россия продолжала сохранять свои войска на территории бывшей Восточной Германии до 1994 года) с целью противодействия базам НАТО в Западной Германии.

После реорганизации Западной Германии и обретения ею независимости от оккупантов (1945–1949 гг.) в октябре 1949 г. в Восточной Германии была создана ГДР. Возникновение двух суверенных государств закрепило раздел Германии 1945 г. [33] 10 марта 1952 г. (в том, что станет известно как « Сталинская нота ») Генеральный секретарь Коммунистической партии Советского Союза Иосиф Сталин выступил с предложением о воссоединении Германии с политикой нейтралитета, без каких-либо условий в отношении экономической политики и с гарантиями «прав человека и основных свобод, включая свободу слова, печати, вероисповедания, политических убеждений и собраний», а также свободной деятельности демократических партий и организаций. [34] Запад возразил; воссоединение тогда не было приоритетом для руководства Западной Германии, и державы НАТО отклонили это предложение, заявив, что Германия должна иметь возможность вступить в НАТО и что такие переговоры с Советским Союзом будут рассматриваться как капитуляция.

В 1949 году Советы передали контроль над Восточной Германией СЕПГ во главе с Вильгельмом Пиком (1876–1960), который стал президентом ГДР и занимал этот пост до своей смерти, в то время как генеральный секретарь СЕПГ Вальтер Ульбрихт взял на себя большую часть исполнительной власти. Лидер социалистов Отто Гротеволь (1894–1964) стал премьер-министром до своей смерти. [35]

Правительство Восточной Германии осудило неудачи Западной Германии в проведении денацификации и отказалось от связей с нацистским прошлым, посадив в тюрьму многих бывших нацистов и не дав им занимать государственные должности. СЕПГ поставила своей главной целью избавить Восточную Германию от всех следов нацизма . [36] По оценкам, [ когда? ] от 180 000 до 250 000 человек были приговорены к тюремному заключению по политическим мотивам. [37]

На Ялтинской и Потсдамской конференциях 1945 года союзники установили совместную военную оккупацию и управление Германией через Контрольный совет союзников (АКС), военное правительство из четырех держав (США, Великобритания, СССР, Франция) , действовавшее до восстановления суверенитета Германии. В Восточной Германии Советская оккупационная зона (СЗО — Sowjetische Besatzungszone ) включала пять земель ( Länder ): Мекленбург-Передняя Померания , Бранденбург , Саксония , Саксония-Анхальт и Тюрингия . [38] Разногласия по поводу политики, которой надлежало следовать в оккупированных зонах, быстро привели к разрыву сотрудничества между четырьмя державами, и Советы управляли своей зоной без учета политики, проводимой в других зонах. Советы вышли из АКС в 1948 году; впоследствии, по мере того как остальные три зоны все больше объединялись и получали самоуправление, советская администрация учредила в своей зоне отдельное социалистическое правительство. [39] [40]

Спустя семь лет после Потсдамского соглашения союзников 1945 года об общей германской политике, СССР посредством Сталинской ноты (10 марта 1952 года) предложил воссоединение Германии и отделение сверхдержав от Центральной Европы, что три западных союзника (США, Франция, Великобритания) отвергли. Советский лидер Иосиф Сталин , коммунистический сторонник воссоединения, умер в начале марта 1953 года. Аналогичным образом, Лаврентий Берия , первый заместитель премьер-министра СССР, добивался воссоединения Германии, но он был отстранен от власти в том же году, прежде чем смог предпринять какие-либо действия по этому вопросу. Его преемник Никита Хрущев отверг воссоединение как эквивалент возвращения Восточной Германии для аннексии Западом; поэтому воссоединение не рассматривалось до падения Берлинской стены в 1989 году.

Восточная Германия считала Восточный Берлин своей столицей, а Советский Союз и остальные страны Восточного блока дипломатически признали Восточный Берлин столицей. Однако западные союзники оспаривали это признание, считая весь город Берлин оккупированной территорией, управляемой Союзным контрольным советом . По словам Маргарет Файнштейн, статус Восточного Берлина как столицы в значительной степени не признавался Западом и большинством стран третьего мира. [41] На практике полномочия АКК были поставлены под сомнение холодной войной , статус Восточного Берлина как оккупированной территории в значительной степени стал юридической фикцией , а советский сектор Берлина был полностью интегрирован в ГДР. [42]

Углубляющийся конфликт холодной войны между западными державами и Советским Союзом из-за нерешенного статуса Западного Берлина привел к блокаде Берлина (24 июня 1948 г. – 12 мая 1949 г.). Советская армия инициировала блокаду, остановив все железнодорожные, автомобильные и водные перевозки союзников в Западный Берлин и из него. Союзники противостояли Советам Берлинским воздушным мостом (1948–49 гг.) с продовольствием, топливом и припасами в Западный Берлин. [43]

21 апреля 1946 года Коммунистическая партия Германии ( Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands – KPD) и часть Социал-демократической партии Германии ( Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands – SPD) в советской зоне объединились в Социалистическую единую партию Германии (SED – Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands ), которая затем выиграла выборы в октябре 1946 года . Правительство СЕПГ национализировало инфраструктуру и промышленные предприятия.

В марте 1948 года Немецкая экономическая комиссия ( Deutsche Wirtschaftskomission –DWK) под руководством ее председателя Генриха Рау взяла на себя административную власть в советской оккупационной зоне, став, таким образом, предшественником правительства Восточной Германии. [44] [45]

7 октября 1949 года СЕПГ основала Немецкую Демократическую Республику (ГДР), основанную на социалистической политической конституции, устанавливающей ее контроль над Антифашистским национальным фронтом Германской Демократической Республики (НФ, Nationale Front der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik ), всеобъемлющим альянсом всех партий и массовых организаций Восточной Германии. НФ был создан для участия в выборах в Народную палату ( Volkskammer ), парламент Восточной Германии. Первым и единственным президентом Германской Демократической Республики был Вильгельм Пик . Однако после 1950 года политическая власть в Восточной Германии находилась в руках первого секретаря СЕПГ Вальтера Ульбрихта . [5]

.jpg/440px-Opvolger_van_Pieck,_Walter_Ulbricht,_Bestanddeelnr_911-5926_(cropped).jpg)

16 июня 1953 года рабочие, строящие новый бульвар Сталиналлее в Восточном Берлине в соответствии с официально обнародованными Шестнадцатью принципами городского дизайна ГДР , взбунтовались против 10%-ного увеличения производственной квоты. Первоначально протест рабочих, вскоре акция охватила все население, и 17 июня аналогичные протесты прошли по всей ГДР, в которых бастовали более миллиона человек примерно в 700 городах и поселках. Опасаясь антикоммунистической контрреволюции , 18 июня 1953 года правительство ГДР привлекло советские оккупационные войска для помощи полиции в прекращении беспорядков; около пятидесяти человек были убиты и 10 000 заключены в тюрьму (см. Восстание 1953 года в Восточной Германии ). [ необходимо разъяснение ] [46] [47]

Немецкие военные репарации , причитающиеся Советам, разорили Советскую зону оккупации и серьезно ослабили экономику Восточной Германии. В период 1945–46 годов Советы конфисковали и вывезли в СССР около 33% промышленных предприятий и к началу 1950-х годов извлекли около 10 миллиардов долларов США в виде репараций в виде сельскохозяйственной и промышленной продукции. [48] Бедность Восточной Германии, вызванная или усугубленная репарациями, спровоцировала Republikflucht («дезертирство из республики») в Западную Германию, что еще больше ослабило экономику ГДР. Западные экономические возможности вызвали утечку мозгов . В ответ ГДР закрыла внутреннюю границу Германии , и в ночь на 12 августа 1961 года солдаты Восточной Германии начали возводить Берлинскую стену . [49]

.jpg/440px-Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-R1220-401,_Erich_Honecker_(cropped).jpg)

В 1971 году Ульбрихт был отстранён от руководства после того, как советский лидер Леонид Брежнев поддержал его отставку; [50] его сменил Эрих Хонеккер . В то время как правительство Ульбрихта экспериментировало с либеральными реформами, правительство Хонеккера отменило их. Новое правительство ввело новую конституцию Восточной Германии , которая определяла Германскую Демократическую Республику как «республику рабочих и крестьян». [51]

Первоначально Восточная Германия претендовала на исключительный мандат для всей Германии, что поддерживалось большинством стран коммунистического блока. Она утверждала, что Западная Германия была незаконно созданным марионеточным государством НАТО. Однако с 1960-х годов Восточная Германия начала признавать себя отдельной страной от Западной Германии и разделять наследие объединенного немецкого государства 1871–1945 годов . Это было формализовано в 1974 году, когда пункт о воссоединении был удален из пересмотренной конституции Восточной Германии. Западная Германия, напротив, утверждала, что она является единственным законным правительством Германии. С 1949 года до начала 1970-х годов Западная Германия утверждала, что Восточная Германия была незаконно созданным государством. Она утверждала, что ГДР была советским марионеточным государством, и часто называла ее «советской оккупационной зоной». Союзники Западной Германии разделяли эту позицию до 1973 года. Восточная Германия была признана в первую очередь социалистическими странами и арабским блоком , а также некоторыми «разрозненными сочувствующими». [52] Согласно доктрине Хальштейна (1955 г.), Западная Германия не устанавливала (официальных) дипломатических отношений ни с одной страной, кроме Советского Союза, которая признавала суверенитет Восточной Германии.

В начале 1970-х годов Ostpolitik («Восточная политика») «Изменений через сближение» прагматичного правительства канцлера ФРГ Вилли Брандта установила нормальные дипломатические отношения с государствами Восточного блока . Эта политика привела к Московскому договору (август 1970 г.), Варшавскому договору (декабрь 1970 г.), Соглашению четырех держав по Берлину (сентябрь 1971 г.), Транзитному соглашению (май 1972 г.) и Основному договору (декабрь 1972 г.), который отказался от любых отдельных претензий на исключительный мандат над Германией в целом и установил нормальные отношения между двумя Германиями. Обе страны были приняты в Организацию Объединенных Наций 18 сентября 1973 года. Это также увеличило число стран, признавших Восточную Германию, до 55, включая США, Великобританию и Францию, хотя эти три страны по-прежнему отказывались признавать Восточный Берлин столицей и настаивали на конкретном положении в резолюции ООН, принимающей обе Германии в ООН с этой целью. [52] Следуя Ostpolitik, западногерманская точка зрения заключалась в том, что Восточная Германия была фактическим правительством в рамках единой немецкой нации и юридическим государственным образованием частей Германии за пределами Федеративной Республики. Федеративная Республика продолжала утверждать, что она не могла в рамках своих собственных структур признать ГДР де-юре как суверенное государство в соответствии с международным правом; но она полностью признавала, что в рамках структур международного права ГДР была независимым суверенным государством. В отличие от этого, Западная Германия тогда рассматривала себя как находящуюся в пределах своих собственных границ, не только фактическим и юридическим правительством, но и единственным законным представителем де-юре бездействующей «Германии как целого». [53] Каждая из двух Германий отказалась от любых претензий на международное представительство друг друга; они признали, что это обязательно подразумевает взаимное признание друг друга как способных представлять свое собственное население де-юре , участвуя в международных органах и соглашениях, таких как Организация Объединенных Наций и Хельсинкский Заключительный акт .

Эта оценка Основного договора была подтверждена в решении Федерального конституционного суда в 1973 году; [54]

Германская Демократическая Республика в международно-правовом смысле является государством и как таковой субъектом международного права. Этот вывод не зависит от признания Германской Демократической Республики в международном праве Федеративной Республикой Германия. Такое признание не только никогда официально не объявлялось Федеративной Республикой Германия, но, напротив, неоднократно прямо отвергалось. Если поведение Федеративной Республики Германия по отношению к Германской Демократической Республике оценивать в свете ее политики разрядки, в частности, заключение Договора как фактическое признание, то его можно понимать только как фактическое признание особого рода. Особенностью этого Договора является то, что, хотя он является двусторонним Договором между двумя государствами, к которому применяются нормы международного права и который, как и любой другой международный договор, обладает юридической силой, он заключается между двумя государствами, которые являются частями все еще существующего, хотя и недееспособного, поскольку не реорганизованного, всеобъемлющего Государства Целой Германии с единым политическим телом. [55]

С 1972 года поездки между ГДР и Польшей, Чехословакией и Венгрией стали безвизовыми. [56]

С самого начала новообразованная ГДР пыталась установить свою собственную отдельную идентичность. [57] Из-за имперского и военного наследия Пруссии СЕПГ отвергла преемственность между Пруссией и ГДР. СЕПГ уничтожила ряд символических реликвий бывшей прусской аристократии ; юнкерские усадьбы были снесены, Берлинский городской дворец был разрушен, а на его месте был построен Дворец Республики , а конная статуя Фридриха Великого была удалена из Восточного Берлина. Вместо этого СЕПГ сосредоточилась на прогрессивном наследии немецкой истории, включая роль Томаса Мюнцера в немецкой крестьянской войне 1524–1525 годов и роль, которую сыграли герои классовой борьбы во время индустриализации Пруссии. Другие известные деятели и реформаторы из истории Пруссии, такие как Карл Фрайхерр фон Штайн (1757–1831), Карл Август фон Гарденберг (1750–1822), Вильгельм фон Гумбольдт (1767–1835) и Герхард фон Шарнхорст (1755–1813) были поддержаны СЕПГ как примеры и образцы для подражания.

Коммунистический режим ГДР основывал свою легитимность на борьбе антифашистских активистов. Форма сопротивления «культ» была установлена в мемориальном комплексе лагеря Бухенвальд с созданием музея в 1958 году и ежегодным празднованием клятвы Бухенвальда, принятой 19 апреля 1945 года заключенными, которые поклялись бороться за мир и свободу. В 1990-х годах «государственный антифашизм» ГДР уступил место «государственному антикоммунизму» ФРГ. С тех пор доминирующая интерпретация истории ГДР, основанная на концепции тоталитаризма, привела к эквивалентности коммунизма и нацизма. [58] Историк Анне-Катлин Тиллак-Граф показывает с помощью газеты Neues Deutschland , как национальные мемориалы Бухенвальд , Заксенхаузен и Равенсбрюк были политически инструментализированы

в ГДР, особенно во время празднования освобождения концлагерей. [59]

Хотя официально она была создана в противовес «фашистскому миру» в Западной Германии, в 1954 году 32% сотрудников органов государственного управления были бывшими членами нацистской партии . Однако в 1961 году доля бывших членов НСДАП среди старших сотрудников администрации МВД составляла менее 10% в ГДР по сравнению с 67% в ФРГ. [60] В то время как в Западной Германии проводилась работа по увековечению памяти о возрождении нацизма, на Востоке этого не было. Действительно, как отмечает Аксель Доссманн, профессор истории в Йенском университете , «это явление было полностью скрыто. Для государства-СЕПГ (Восточногерманская коммунистическая партия) было невозможно допустить существование неонацистов, поскольку основой ГДР должно было стать антифашистское государство. Штази следила за ними, но их считали чужаками или толстокожими хулиганами. Эти молодые люди росли, слушая двусмысленные разговоры. В школе запрещалось говорить о Третьем рейхе, а дома их бабушки и дедушки рассказывали им, как благодаря Гитлеру у нас появились первые автомагистрали». 17 октября 1987 года около тридцати скинхедов яростно бросились на толпу из 2000 человек на рок-концерте в Сионскирхе без вмешательства полиции. [61] В 1990 году писательница Фрейя Клир получила угрозу смерти за написание эссе об антисемитизме и ксенофобии в ГДР. Вице-президент СДПА Вольфганг Тирзе , со своей стороны, жаловался в Die Welt на рост крайне правых в повседневной жизни жителей бывшей ГДР, в частности террористической группировки NSU, а немецкая журналистка Одиль Беняхия-Койдер объяснила, что «неслучайно неонацистская партия НДПГ пережила возрождение на Востоке». [62]

Историк Соня Комб отмечает, что до 1990-х годов большинство западногерманских историков описывали высадку в Нормандии в июне 1944 года как «вторжение», оправдывали вермахт от его ответственности за геноцид евреев и сфабриковали миф о дипломатическом корпусе, который «не знал». Напротив, Освенцим никогда не был табу в ГДР. Преступления нацистов были предметом обширных кино-, театральных и литературных постановок. В 1991 году 16% населения в Западной Германии и 6% в Восточной Германии имели антисемитские предрассудки. В 1994 году 40% западных немцев и 22% восточных немцев считали, что геноциду евреев уделяется слишком много внимания. [60]

Историк Ульрих Пфайль , тем не менее, напоминает о том, что антифашистское поминовение в ГДР имело «агиографический и индоктринационный характер». [63] Как и в случае с памятью о главных героях немецкого рабочего движения и жертвах лагерей, оно было «инсценировано, подвергнуто цензуре, заказано» и в течение 40 лет режима было инструментом легитимации, репрессий и поддержания власти. [63]

В мае 1989 года, после широко распространенного общественного возмущения по поводу фальсификации результатов выборов в местные органы власти, многие граждане ГДР подали заявления на выездные визы или покинули страну вопреки законам ГДР. Толчком к этому исходу восточных немцев стало снятие электрифицированного забора вдоль границы Венгрии с Австрией 2 мая 1989 года. Хотя формально венгерская граница все еще была закрыта, многие восточные немцы воспользовались возможностью въехать в Венгрию через Чехословакию , а затем нелегально пересечь границу из Венгрии в Австрию и далее в Западную Германию. [64] К июлю 25 000 восточных немцев пересекли границу с Венгрией; [65] большинство из них не стали рискованно пересекать границу с Австрией, а остались в Венгрии или попросили убежища в посольствах Западной Германии в Праге или Будапеште .

Открытие пограничных ворот между Австрией и Венгрией на Панъевропейском пикнике 19 августа 1989 года затем запустило цепную реакцию, приведшую к концу ГДР и распаду Восточного блока. Это был самый крупный массовый побег из Восточной Германии со времен строительства Берлинской стены в 1961 году. Идея открытия границы на церемонии принадлежала Отто фон Габсбургу , который предложил ее Миклошу Немету , тогдашнему премьер-министру Венгрии, который продвигал эту идею. [66] Организаторы пикника, Габсбург и венгерский государственный министр Имре Пожгай , который не присутствовал на мероприятии, рассматривали запланированное мероприятие как возможность проверить реакцию Михаила Горбачева на открытие границы по железному занавесу . В частности, это было проверкой того, даст ли Москва советским войскам, дислоцированным в Венгрии, команду на вмешательство. Широкая реклама запланированного пикника была сделана Панъевропейским союзом с помощью плакатов и листовок среди отдыхающих из ГДР в Венгрии. Австрийское отделение Панъевропейского союза , которое тогда возглавлял Карл фон Габсбург , распространило тысячи брошюр, приглашающих граждан ГДР на пикник недалеко от границы в Шопроне (недалеко от границы Венгрии с Австрией). [67] [68] [69] Местные организаторы в Шопроне ничего не знали о возможных беженцах из ГДР, но предполагали местную вечеринку с участием Австрии и Венгрии. [70] Но с массовым исходом на Панъевропейском пикнике последующее нерешительное поведение Социалистической единой партии Восточной Германии и невмешательство Советского Союза прорвали плотины. Таким образом, барьер Восточного блока был разрушен. Десятки тысяч восточных немцев, предупрежденных средствами массовой информации, направились в Венгрию, которая больше не была готова держать свои границы полностью закрытыми или заставлять свои пограничные войска открывать огонь по беглецам. Руководство ГДР в Восточном Берлине не решилось полностью закрыть границы своей страны. [67] [69] [71] [72]

Следующий важный поворотный момент в исходе произошел 10 сентября 1989 года, когда министр иностранных дел Венгрии Дьюла Хорн объявил, что его страна больше не будет ограничивать передвижение из Венгрии в Австрию. В течение двух дней 22 000 восточных немцев пересекли границу с Австрией; еще десятки тысяч сделали это в последующие недели. [64]

Многие другие граждане ГДР выступили против правящей партии , особенно в городе Лейпциг . Лейпцигские демонстрации стали еженедельным явлением, на первой демонстрации 2 октября собралось 10 000 человек, а к концу месяца их число достигло, по оценкам, 300 000 человек. [73] Протесты были превзойдены в Восточном Берлине, где 4 ноября против режима выступило полмиллиона демонстрантов. [73] Курт Мазур , дирижер Лейпцигского оркестра Гевандхаус , вел местные переговоры с правительством и проводил городские собрания в концертном зале. [74] Демонстрации в конечном итоге привели к отставке Эриха Хонеккера в октябре; его заменил немного более умеренный коммунист Эгон Кренц . [75]

Массовая демонстрация в Восточном Берлине 4 ноября совпала с официальным открытием Чехословакией границы с Западной Германией. [76] Поскольку Запад стал более доступным, чем когда-либо прежде, 30 000 восточных немцев пересекли границу через Чехословакию только за первые два дня. Чтобы попытаться остановить отток населения, СЕПГ предложила закон, ослабляющий ограничения на поездки. Когда Народная палата отклонила его 5 ноября, Кабинет министров и Политбюро ГДР ушли в отставку. [76] Это оставило Кренцу и СЕПГ только один путь: полную отмену ограничений на поездки между Востоком и Западом.

9 ноября 1989 года были открыты несколько участков Берлинской стены, в результате чего тысячи восточных немцев впервые за почти 30 лет свободно пересекли Западный Берлин и Западную Германию. Месяц спустя Кренц ушел в отставку, и СЕПГ начала переговоры с лидерами зарождающегося демократического движения Neues Forum , чтобы назначить свободные выборы и начать процесс демократизации. В рамках этого процесса СЕПГ исключила из конституции Восточной Германии пункт, гарантировавший коммунистам руководство государством. Изменение было одобрено Народной палатой 1 декабря 1989 года 420 голосами против 0. [77]

Восточная Германия провела свои последние выборы в марте 1990 года . Победителем стал Альянс за Германию , коалиция во главе с восточногерманским отделением Христианско-демократического союза Западной Германии , которая выступала за скорейшее воссоединение. Были проведены переговоры ( переговоры 2+4 ) с участием двух немецких государств и бывших союзников , которые привели к соглашению об условиях объединения Германии. Двумя третями голосов в Народной палате 23 августа 1990 года Германская Демократическая Республика объявила о своем присоединении к Федеративной Республике Германии. Пять первоначальных восточногерманских государств , которые были упразднены в результате перераспределения округов 1952 года, были восстановлены. [75] 3 октября 1990 года пять земель официально присоединились к Федеративной Республике Германии, в то время как Восточный и Западный Берлин объединились в третий город-государство (таким же образом, как Бремен и Гамбург ). 1 июля валютный союз предшествовал политическому союзу: «Остмарка» была упразднена, а западногерманская «Немецкая марка» стала единой валютой.

Хотя декларация Народной палаты о присоединении к Федеративной Республике инициировала процесс воссоединения, сам акт воссоединения (со множеством конкретных положений, условий и оговорок, некоторые из которых включали внесение поправок в Основной закон Западной Германии) был конституционно достигнут последующим Договором об объединении от 31 августа 1990 года, то есть посредством обязывающего соглашения между бывшей Демократической Республикой и Федеративной Республикой, которые теперь признавали друг друга как отдельные суверенные государства в международном праве. [78] Затем договор был принят до согласованной даты объединения как Народной палатой, так и Бундестагом большинством в две трети голосов, требуемым конституцией, что привело, с одной стороны, к прекращению существования ГДР, а с другой — к согласованным поправкам к Основному закону Федеративной Республики.

Большое экономическое и социально-политическое неравенство между бывшими Германиями требовало государственных субсидий для полной интеграции Германской Демократической Республики в Федеративную Республику Германия. Из-за последовавшей за этим деиндустриализации в бывшей Восточной Германии причины провала этой интеграции продолжают обсуждаться. Некоторые западные комментаторы утверждают, что депрессивная восточная экономика является естественным последствием явно неэффективной командной экономики . Но многие восточногерманские критики утверждают, что стиль приватизации в стиле шоковой терапии , искусственно высокий обменный курс, предложенный для остмарки , и скорость, с которой был реализован весь процесс, не оставили возможности для адаптации восточногерманских предприятий. [j]

В политической истории Восточной Германии было четыре периода. [79] К ним относятся: 1949–1961 годы, когда строился социализм; 1961–1970 годы, после того как Берлинская стена перекрыла пути к отступлению, были периодом стабильности и консолидации; 1971–1985 годы были названы эпохой Хонеккера и ознаменовались более тесными связями с Западной Германией; и 1985–1990 годы ознаменовались упадком и исчезновением Восточной Германии.

Правящей политической партией в Восточной Германии была Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands ( Социалистическая единая партия Германии , СЕПГ). Она была создана в 1946 году в результате слияния Коммунистической партии Германии (КПГ) и Социал-демократической партии Германии (СДПГ) под руководством Советского Союза в контролируемой Советским Союзом зоне. Однако СЕПГ быстро трансформировалась в полноценную Коммунистическую партию, поскольку более независимые социал-демократы были вытеснены. [80]

Потсдамское соглашение обязывало Советы поддерживать демократическую форму правления в Германии, хотя советское понимание демократии радикально отличалось от западного. Как и в других странах советского блока, некоммунистические политические партии были разрешены. Тем не менее, каждая политическая партия в ГДР была вынуждена присоединиться к Национальному фронту демократической Германии , широкой коалиции партий и массовых политических организаций, включая:

Партии-члены были почти полностью подчинены СЕПГ и должны были принять ее « руководящую роль » как условие своего существования. Однако партии имели представительство в Народной палате и получили некоторые посты в правительстве.

В Народную палату входили также представители массовых организаций, таких как Свободная немецкая молодёжь ( Freie Deutsche Jugend или FDJ ) или Свободный немецкий союз профсоюзов . Также существовала Демократическая федерация женщин Германии , имевшая места в Народной палате .

Важные непарламентские массовые организации в восточногерманском обществе включали Германское гимнастическое и спортивное общество ( Deutscher Turn- und Sportbund или DTSB ) и Народную солидарность ( Volkssolidarität ), организацию для пожилых людей. Другим заметным обществом было Общество германо-советской дружбы .

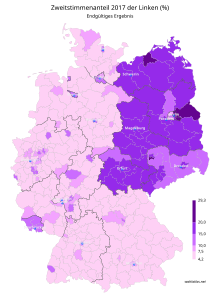

После падения социализма СЕПГ была переименована в « Партию демократического социализма » (ПДС), которая просуществовала десятилетие после воссоединения, прежде чем слиться с западногерманской WASG и сформировать Левую партию ( Die Linke ). Левая партия продолжает оставаться политической силой во многих частях Германии, хотя и значительно менее могущественной, чем СЕПГ. [81]

Флаг Германской Демократической Республики состоял из трех горизонтальных полос в традиционных немецко-демократических цветах: черном, красном и золотом, с национальным гербом ГДР посередине, состоящим из молота и циркуля, окруженных венком из кукурузы как символом союза рабочих, крестьян и интеллигенции. Первые проекты герба Фрица Берендта содержали только молот и венок из кукурузы, как выражение рабоче-крестьянского государства. Окончательный вариант был в основном основан на работе Хайнца Белинга.

Законом от 26 сентября 1955 года был определен государственный герб с молотом, циркулем и венком из кукурузы, поскольку государственный флаг продолжает черно-красно-золотой. Законом от 1 октября 1959 года герб был вставлен в государственный флаг. До конца 1960-х годов публичная демонстрация этого флага в Федеративной Республике Германии и Западном Берлине считалась нарушением конституции и общественного порядка и пресекалась полицейскими мерами (ср. Декларацию министров внутренних дел Федерации и земель, октябрь 1959 года). Только в 1969 году федеральное правительство постановило, что «полиция больше нигде не должна вмешиваться в использование флага и герба ГДР».

По просьбе DSU первая свободно избранная Народная палата ГДР 31 мая 1990 года постановила, что государственный герб ГДР должен быть удален в течение недели в общественных зданиях и на них. Тем не менее, вплоть до официального конца республики, он продолжал использоваться различными способами, например, на документах.

Текст Воскресшего из руин национального гимна ГДР принадлежит Йоханнесу Р. Бехеру, мелодия — Ханнсу Эйслеру. Однако с начала 1970-х годов и до конца 1989 года текст гимна больше не исполнялся из-за отрывка «Deutschland einig Vaterland».

Первый штандарт президента имел форму прямоугольного флага в черно-красно-золотых тонах с надписью «Президент» желтым цветом на красной полосе, а также «DDR» (вопреки официальной аббревиатуре с точками) на полосе ниже черными буквами. Флаг был окружен полосой желтого цвета. Оригинал штандарта находится в Немецком историческом музее в Берлине.

На флагах воинских частей ГДР был изображен государственный герб с венком из двух оливковых ветвей на красном фоне в черно-красно-золотом полотнище.

Флаги Народного флота для боевых кораблей и катеров имели герб с венком из оливковых ветвей на красном, для вспомогательных кораблей и катеров на синем полотнище флага с узкой и расположенной по центру черно-красно-золотой полосой. Как и Gösch, государственный флаг использовался в уменьшенном виде.

Корабли и катера Береговой пограничной бригады на Балтийском море и катера пограничных войск ГДР на Эльбе и Одере несли на лике зеленую полосу, как и служебный флаг пограничных войск.

После вступления в организацию « Пионеры Тельмана» , объединявшую школьников в возрасте от 6 до 14 лет, подростки из Восточной Германии обычно вступали в FDJ .

Young Pioneers and the Thälmann Pioneers, was a youth organisation of schoolchildren aged 6 to 14 in East Germany.[82] They were named after Ernst Thälmann, the former leader of the Communist Party of Germany, who was executed at the Buchenwald concentration camp.[83]

The group was a subdivision of the Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ, Free German Youth), East Germany's youth movement.[84] It was founded on 13 December 1948 and broke apart in 1989 on German reunification.[85] In the 1960s and 1970s, nearly all schoolchildren between ages 6 and 14 were organised into Young Pioneer or Thälmann Pioneer groups, with the organisations having "nearly two million children" collectively by 1975.[85]

The pioneer group was loosely based on Scouting, but organised in such a way as to teach schoolchildren aged 6 – 14 socialist ideology and prepare them for the Freie Deutsche Jugend, the FDJ.[85]

The program was designed to follow the Soviet Pioneer program Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization. The pioneers' slogan was Für Frieden und Sozialismus seid bereit – Immer bereit" ("For peace and socialism be ready – always ready"). This was usually shortened to "Be ready – always ready". This was recited at the raising of the flag. One person said the first part, "Be ready!": this was usually the pioneer leader, the teacher or the head of the local pioneer group. The pioneers all answered "Always ready", stiffening their right hand and placing it against their forehead with the thumb closest and their little finger facing skywards.[85]

Both Pioneer groups would often have massive parades, honoring and celebrating the Socialist success of their nations.

Membership in the Young Pioneers and the Thälmann Pioneers was formally voluntary. On the other hand, it was taken for granted by the state and thus by the school as well as by many parents. In practice, the initiative for the admission of all students in a class came from the school. As the membership quota of up to 98 percent of the students (in the later years of the GDR) shows, the six- or ten-year-olds (or their parents) had to become active on their own in order not to become members. Nevertheless, there were also children who did not become members. Rarely, students were not admitted because of poor academic performance or bad behavior "as a punishment" or excluded from further membership.

The pioneers' uniform consisted of white shirts and blouses bought by their parents, along with blue trousers or skirts until the 1970s and on special occasions. But often the only thing worn was the most important sign of the future socialist – the triangular necktie. At first this was blue, but from 1973, the Thälmann pioneers wore a red necktie like the pioneers in the Soviet Union, while the Young Pioneers kept the blue one. Pioneers wore their uniforms at political events and state holidays such as the workers' demonstrations on May Day, as well as at school festivals and pioneer events.[85]

The pioneer clothing consisted of white blouses and shirts that could be purchased in sporting goods stores. On the left sleeve there was a patch with the embroidered emblem of the pioneer organization and, if necessary, a rank badge with stripes in the color of the scarf. These rank badges were three stripes for Friendship Council Chairmen, two stripes for Group Council Chairmen and Friendship Council members, one stripe for all other Group Council members. In some cases, symbols for special functions were also sewn on at this point, for example a red cross for a boy paramedic. Dark blue trousers or skirts were worn and a dark blue cap served as a headgear with the pioneer emblem as a cockade. At the beginning of the 1970s, a windbreaker/blouson and a dark red leisure blouse were added.

However, the pioneer clothing was only worn completely on special occasions, such as flag appeals, commemoration days or festive school events, but it was usually not prescribed.

From the 1960s, the requirement of trousers/skirt was dispensed with in many places, and the dress code was also relaxed with regard to the cap. For pioneer afternoons or other activities, often only the triangular scarf was worn. In contrast to the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries, a blue scarf was common in the GDR. It was not until 1973, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the organization, that the red scarf was introduced for the Thälmann pioneers, while the young pioneers remained with the blue scarf. The change of color of the scarf was solemnly designed in the pioneer organization.

From 1988 there was an extended clothing range, consisting of a Nicki in the colors white, light yellow, turquoise or pink (with an imprint of the symbol of the pioneer organization), long and short trousers with a snap belt and, for the colder months, a lined windbreaker in red for girls and gray for boys.

Suitable pioneers were trained as paramedics; after their training, they wore the badge "Young Paramedic".

The Pioneer songs were sung at any opportunity, including the following titles:

Freie Deutsche Jugend, organization was meant for young people, both male and female, between the ages of 14 and 25 and comprised about 75% of the young population of former East Germany.[87] In 1981–1982, this meant 2.3 million members.[88] After being a member of the Thälmann Pioneers, which was for schoolchildren ages 6 to 14, East German youths would usually join the FDJ.[89]

The FDJ increasingly developed into an instrument of communist rule and became a member of the 'democratic bloc' in 1950.[86] However, the FDJ's focus of 'happy youth life', which had characterised the 1940s, was increasingly marginalised following Walter Ulbricht's emphasis of the 'accelerated construction of socialism' at the 4th Parliament and a radicalisation of SED policy in July 1952.[90] In turn, a more severe anti-religious agenda, whose aim was to obstruct the Church youths' work, grew within the FDJ, ultimately reaching a high point in mid-April 1953 when the FDJ newspaper Junge Welt reported on details of the 'criminal' activities of the 'illegal' Junge Gemeinden FDJ gangs were sent to church meetings to heckle those inside and school tribunals interrogated or expelled students who refused to join the FDJ for religious reasons.[91]

Upon request, the young people were admitted to the FDJ from the age of 14. Membership was voluntary according to the statutes, but non-members had to fear considerable disadvantages in admission to secondary schools as well as in the choice of studies and careers and were also exposed to strong pressure from line-loyal teachers to join the organization. By the end of 1949, around one million young people had joined it, which corresponded to almost a third of the young people. Only in Berlin, where other youth organizations were also admitted due to the four-power status, the proportion of FDJ members in youth was limited to just under 5 percent in 1949. In 1985, the organization had about 2.3 million members, corresponding to about 80 percent of all GDR youths between the ages of 14 and 25. Most young people tacitly ended their FDJ membership after completing their apprenticeship or studies when they entered the workforce. However, during the period of military service in the NVA, those responsible (political officer, FDJ secretary) attached great importance to reviving FDJ membership. The degree of organisation was much higher in urban areas than in rural areas.

The FDJ clothing was the blue FDJ shirt ("blue shirt") – for girls the blue FDJ blouse – with the FDJ emblem of the rising sun on the left sleeve. The greeting of the FDJers was "friendship". Until the end of the GDR, the income-dependent membership fee was between 0.30 and 5.00 marks per month.

The Festival of Political Songs (‹See Tfd›German: Festival des politischen Liedes) was one of the largest music events in East Germany, held between 1970 and 1990. It was hosted by the Free German Youth and featured international artists.

The blue shirt (also: FDJ shirt or FDJ blouse) was since 1948 the official organizational clothing of the GDR youth organization Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ). On official occasions, FDJ members had to wear their blue shirts. The FDJ shirt – an FDJ blouse for girls – was a long-sleeved shirt of blue color with a folding collar, epaulettes and chest pockets. On the left sleeve was the FDJ symbol of the rising sun sewn up. Until the 1970s, the blue shirts were only made of cotton, later there was a cheaper variant made of polyester mixture.

The epaulettes of the blue shirt, in contrast to epaulettes on military uniforms, did not serve to make visible rank or unit membership, but were used at most to put a beret through. Official functions in the FDJ, for example FDJ secretary of a school or apprentice class, had no rank badges and could not be read on the FDJ shirt. However, the members of the FDJ order groups officially wore the FDJ shirt together with a red armband during their missions.

From the 1970s onwards, official patches and pins were issued for certain events, which could be worn on the FDJ shirt. There was no fixed wearing style. The orders and decorations that ordinary FDJ members received until the end of their membership at the age of 19 to 24 – usually the badge of good knowledge – were usually not worn. As a rule, only full-time FDJ members on the way to the nomenklatura at an older age achieved awards, which were also worn.

Until 1952, East Germany comprised the capital, East Berlin (though legally it was not fully part of the GDR's territory), and the five German states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in 1947 renamed Mecklenburg), Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt (named Province of Saxony until 1946), Thuringia, and Saxony, their post-war territorial demarcations approximating the pre-war German demarcations of the Middle German Länder (states) and Provinzen (provinces of Prussia). The western parts of two provinces, Pomerania and Lower Silesia, the remainder of which were annexed by Poland, remained in the GDR and were attached to Mecklenburg and Saxony, respectively.

The East German Administrative Reform of 1952 established 14 Bezirke (districts) and de facto disestablished the five Länder. The new Bezirke, named after their district centres, were as follows: (i) Rostock, (ii) Neubrandenburg, and (iii) Schwerin created from the Land (state) of Mecklenburg; (iv) Potsdam, (v) Frankfurt (Oder), and (vii) Cottbus from Brandenburg; (vi) Magdeburg and (viii) Halle from Saxony-Anhalt; (ix) Leipzig, (xi) Dresden, and (xii) Karl-Marx-Stadt (Chemnitz until 1953 and again from 1990) from Saxony; and (x) Erfurt, (xiii) Gera, and (xiv) Suhl from Thuringia.

East Berlin was made the country's 15th Bezirk in 1961 but retained special legal status until 1968, when the residents approved the new (draft) constitution. Despite the city as a whole being legally under the control of the Allied Control Council, and diplomatic objections of the Allied governments, the GDR administered the Bezirk of Berlin as part of its territory.

After receiving wider international diplomatic recognition in 1972–73, the GDR began active cooperation with Third World socialist governments and national liberation movements. While the USSR was in control of the overall strategy and Cuban armed forces were involved in the actual combat (mostly in the People's Republic of Angola and socialist Ethiopia), the GDR provided experts for military hardware maintenance and personnel training, and oversaw creation of secret security agencies based on its own Stasi model.

Already in the 1960s, contacts were established with Angola's MPLA, Mozambique's FRELIMO and the PAIGC in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde. In the 1970s official cooperation was established with other socialist states, such as the People's Republic of the Congo, People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, Somali Democratic Republic, Libya, and the People's Republic of Benin.

The first military agreement was signed in 1973 with the People's Republic of the Congo. In 1979 friendship treaties were signed with Angola, Mozambique and Ethiopia.

It was estimated that altogether, 2,000–4,000 DDR military and security experts were dispatched to Africa. In addition, representatives from African and Arab countries and liberation movements underwent military training in the GDR.[92]

East Germany pursued an anti-Zionist policy; Jeffrey Herf argues that East Germany was waging an undeclared war on Israel.[93] According to Herf, "the Middle East was one of the crucial battlefields of the global Cold War between the Soviet Union and the West; it was also a region in which East Germany played a salient role in the Soviet bloc's antagonism toward Israel."[94] While East Germany saw itself as an "anti-fascist state", it regarded Israel as a "fascist state"[95] and East Germany strongly supported the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in its armed struggle against Israel. In 1974, the GDR government recognized the PLO as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people".[96] The PLO declared the Palestinian state on 15 November 1988 during the First Intifada, and the GDR recognized the state prior to reunification.[97] After becoming a member of the UN, East Germany "made excellent use of the UN to wage political warfare against Israel [and was] an enthusiastic, high-profile, and vigorous member" of the anti-Israeli majority of the General Assembly.[93]

Ba'athist Iraq, due to its wealth of unexploited natural resources, was sought out as an ally of East Germany, with Iraq being the first Arab country to recognise East Germany on 10 May 1969, paving the way for other Arab League states to later do the same. East Germany attempted to play a decisive role in mediating the conflict between the Iraqi Communist Party and the Ba'ath Party and supported the creation of the National Progressive Front. The East German government also attempted to foster close relations with the Ba'athist regime of Hafez al-Assad during the early years of Assad's regime and, as it did in Iraq, used its influence to minimise tensions between the Syrian Communist Party and the Ba'athist regime.[98]

During the Cold War, especially during its early years, the East German government attempted to build closer diplomatic relations and trade links between Iceland and East Germany. By the 1950s, East Germany had become Iceland's fifth largest trading partner. East German influence in Iceland significantly declined in the 1970s and 1980s following a schism between the Socialist Unity Party of Germany and the Icelandic Socialist Party over the Prague Spring, along with free market economic reforms implemented by Iceland during the 1960s.[99]

The government of East Germany had control over a large number of military and paramilitary organisations through various ministries. Chief among these was the Ministry of National Defence. Because of East Germany's proximity to the West during the Cold War (1945–92), its military forces were among the most advanced of the Warsaw Pact. Defining what was a military force and what was not is a matter of some dispute.

The Nationale Volksarmee (NVA) was the largest military organisation in East Germany. It was formed in 1956 from the Kasernierte Volkspolizei (Barracked People's Police), the military units of the regular police (Volkspolizei), when East Germany joined the Warsaw Pact. From its creation, it was controlled by the Ministry of National Defence (East Germany). It was an all-volunteer force until an eighteen-month conscription period was introduced in 1962.[100][101] It was regarded by NATO officers as the best military in the Warsaw Pact.[102]The NVA consisted of the following branches:

The border troops of the Eastern sector were originally organised as a police force, the Deutsche Grenzpolizei, similar to the Bundesgrenzschutz in West Germany. It was controlled by the Ministry of the Interior. Following the remilitarisation of East Germany in 1956, the Deutsche Grenzpolizei was transformed into a military force in 1961, modeled after the Soviet Border Troops, and transferred to the Ministry of National Defense, as part of the National People's Army. In 1973, it was separated from the NVA, but it remained under the same ministry. At its peak, it numbered approximately 47,000 men.

After the NVA was separated from the Volkspolizei in 1956, the Ministry of the Interior maintained its own public order barracked reserve, known as the Volkspolizei-Bereitschaften (VPB). These units were, like the Kasernierte Volkspolizei, equipped as motorised infantry, and they numbered between 12,000 and 15,000 men.

The Ministry of State Security (Stasi) included the Felix Dzerzhinsky Guards Regiment, which was mainly involved with facilities security and plain clothes events security. They were the only public-facing wing of the Stasi. The Stasi numbered around 90,000 men, the Guards Regiment around 11,000–12,000 men.[103][104]

The Kampfgruppen der Arbeiterklasse (combat groups of the working class) numbered around 400,000 for much of their existence, and were organised around factories. The KdA was the political-military instrument of the SED; it was essentially a "party Army". All KdA directives and decisions were made by the ZK's Politbüro. They received their training from the Volkspolizei and the Ministry of the Interior. Membership was voluntary, but SED members were required to join as part of their membership obligation.

Every man was required to serve eighteen months of compulsory military service. For the medically unqualified and conscientious objectors, there were the Baueinheiten (construction units) or the Volkshygienedienst (people's sanitation service), both established in 1964, two years after the introduction of conscription, in response to political pressure by the national Lutheran Protestant Church upon the GDR's government. In the 1970s, East German leaders acknowledged that former construction soldiers and sanitation service soldiers were at a disadvantage when they rejoined the civilian sphere.[citation needed]

There is general consensus among academics that the GDR fulfilled most of the criteria to be considered a totalitarian state.[105] There is, however, ongoing debate as to whether the more positive aspects of the regime can sufficiently dilute the harsher aspects so as to make the totalitarian tag seem excessive. According to the historian Mary Fulbrook:

Even those who are most critical of the concept admit that the regime possessed most, if not all, of the objective traits associated with the term, i.e., rule by a single party or elite that dominated the state machinery; that centrally directed and controlled the economy; mass communication, and all forms of social and cultural organisation; that espoused an official, all-encompassing, utopian (or, depending on one's point of view, dystopian) ideology; and that used physical and mental terror and repression to achieve its goals, mobilise the masses, and silence opposition- all of which was made possible by the buildup of a vast state security service.[106]

The state security service (SSD) was commonly known as the Stasi, and it was fundamental to the socialist leadership's attempts to reach their historical goal. It was an open secret in the GDR that the Stasi read people's mail and tapped phone calls.[107] They also employed a vast network of unofficial informers who would spy on people more directly and report to their Stasi handlers. These collaborators were hired in all walks of life and had access to nearly every organisation in the country. At the end of the GDR in 1990 there were approximately 109,000 still active informants at every grade.[108] Repressive measures carried out by the Stasi can be roughly divided into two main chronological groupings: pre and post 1971, when Honecker came to power. According to the historian Nessim Ghouas, "There was a change in how the Stasi operated under Honecker in 1971. The more brutal aspects of repression seen in the Stalinist era (torture, executions, and physical repression descending from the GDR's earlier days) was changed with a more selective use of power."[109]

The more direct forms of repression such as arrest and torture could mean significant international condemnation for the GDR. However, the Stasi still needed to paralyse and disrupt what it considered to be 'hostile-negative'[110] forces (internal domestic enemies) if the socialist goal was to be properly realised. A person could be targeted by the Stasi for expressing politically, culturally, or religiously incorrect views; for performing hostile acts; or for being a member of a group which was considered sufficiently counter-productive to the socialist state to warrant intervention. As such, writers, artists, youth sub-cultures, and members of the church were often targeted.[111] If after preliminary research the Stasi found an individual warranted action against them then they would open an 'operational case'[111] in regard to them. There were two desirable outcomes for each case: that the person was either arrested, tried, and imprisoned for an ostensibly justified reason, or if this could not be achieved that they were debilitated through the application of Zersetzung (in German, "decomposition") methods.[112] In the Honecker era, Zersetzung became the primary method of Stasi repression, due in large part to an ambition to avoid political fallout from wrongful arrest.[k] Historian Mike Dennis says "Between 1985–1988, the Stasi conducted about 4,500 to 5,000 OVs (operational cases) per year."[111]

Zersetzung methods varied and were tailored depending on the individual being targeted. They are known to have included sending offensive mail to a person's house, the spreading of malicious rumours, banning them from traveling, sabotaging their career, breaking into their house and moving objects around etc. These acts frequently led to unemployment, social isolation, and poor mental health. Many people had various forms of mental or nervous breakdown. Similarly to physical imprisonment, Zersetzung methods had the effect of paralysing a person's ability to operate but with the advantage of the source being unknown or at least unprovable. There is ongoing debate as to whether weaponised directed energy devices, such as X-ray transmitters, were used in combination with the psychological warfare methods of Zersetzung.[113] About 135,000 children were educated in special residential homes; the worst of them was Torgau penal institution (till 1975).[114] The International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims considers that there are between 300,000 and 500,000 victims of direct physical torture, Zersetzung, and gross human rights violations due to the Stasi.[115] Victims of historical Zersetzung can now draw a special pension from the German state.[116]

The East German economy began poorly because of the devastation caused by the Second World War, the loss of so many young soldiers, the disruption of business and transportation, the allied bombing campaigns that decimated cities, and reparations owed to the USSR. The Red Army dismantled and transported to Russia the infrastructure and industrial plants of the Soviet Zone of Occupation. By the early 1950s, the reparations were paid in agricultural and industrial products; and Lower Silesia, with its coal mines and Szczecin, an important natural port, were given to Poland by the decision of Stalin and in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement.[48]

The socialist centrally planned economy of the German Democratic Republic was like that of the USSR. In 1950, the GDR joined the COMECON trade bloc. In 1985, collective (state) enterprises earned 97% of the net national income. To ensure stable prices for goods and services, the state paid 80% of basic supply costs. The estimated 1984 per capita income was $9,800 ($22,600 in 2015 dollars) (this is based on an unreal official exchange rate). In 1976, the average annual growth of the GDP was 5 percent. This made the East German economy the richest in all of the Soviet Bloc until reunification in 1990.[7]

Notable East German exports were photographic cameras, under the Praktica brand; automobiles under the Trabant, Wartburg, and the IFA brands; hunting rifles, sextants, typewriters and wristwatches.

Until the 1960s, East Germans endured shortages of basic foodstuffs such as sugar and coffee. East Germans with friends or relatives in the West (or with any access to a hard currency) and the necessary Staatsbank foreign currency account could afford Western products and export-quality East German products via Intershop. Consumer goods also were available, by post, from the Danish Jauerfood, and Genex companies.

The government used money and prices as political devices, providing highly subsidised prices for a wide range of basic goods and services, in what was known as "the second pay packet".[117] At the production level, artificial prices made for a system of semi-barter and resource hoarding. For the consumer, it led to the substitution of GDR money with time, barter, and hard currencies. The socialist economy became steadily more dependent on financial infusions from hard-currency loans from West Germany. East Germans, meanwhile, came to see their soft currency as worthless relative to the Deutsche Mark (DM).[118]Economic issues would also persist in East Germany after the reunification of the west and the east. According to the federal office of political education (23 June 2009) 'In 1991 alone, 153 billion Deutschmarks had to be transferred to eastern Germany to secure incomes, support businesses and improve infrastructure... by 1999 the total had amounted to 1.634 trillion Marks net... The sums were so large that public debt in Germany more than doubled.'[119]

Loyalty to the SED was a primary criterion for getting a good job – professionalism was secondary to political criteria in personnel recruitment and development.[121]

Beginning in 1963 with a series of secret international agreements, East Germany recruited workers from Poland, Hungary, Cuba, Albania, Mozambique, Angola and North Vietnam. They numbered more than 100,000 by 1989. Many, such as future politician Zeca Schall (who emigrated from Angola in 1988 as a contract worker) stayed in Germany after the Wende.[122]

By the mid-1980s, East Germany possessed a well-developed communications system. There were approximately 3.6 million telephones in usage (21.8 for every 100 inhabitants), and 16,476 Telex stations. Both of these networks were run by the Deutsche Post der DDR (East German Post Office). East Germany was assigned telephone country code +37; in 1991, several months after reunification, East German telephone exchanges were incorporated into country code +49.

An unusual feature of the telephone network was that, in most cases, direct distance dialing for long-distance calls was not possible. Although area codes were assigned to all major towns and cities, they were only used for switching international calls. Instead, each location had its own list of dialing codes with shorter codes for local calls and longer codes for long-distance calls. After unification, the existing network was largely replaced, and area codes and dialing became standardised.

In 1976 East Germany inaugurated the operation of a ground-based radio station at Fürstenwalde for the purpose of relaying and receiving communications from Soviet satellites and to serve as a participant in the international telecommunications organization established by the Soviet government, Intersputnik.

The East German population declined by three million people throughout its forty-one year history, from 19 million in 1948 to 16 million in 1990; of the 1948 population, some four million were deported from the lands east of the Oder-Neisse line, which made the home of millions of Germans part of Poland and the Soviet Union.[123] This was in contrast from Poland, which increased during that time; from 24 million in 1950 (a little more than East Germany) to 38 million (more than twice of East Germany's population). This was primarily a result of emigration – about one quarter of East Germans left the country before the Berlin Wall was completed in 1961,[124] and after that time, East Germany had very low birth rates,[125] except for a recovery in the 1980s when the birth rate in East Germany was considerably higher than in West Germany.[126]

(1988 populations)

Religion became contested ground in the GDR, with the governing communists promoting state atheism, although some people remained loyal to Christian communities.[132] In 1957, the state authorities established a State Secretariat for Church Affairs to handle the government's contact with churches and with religious groups;[133] the SED remained officially atheist.[134]

In 1950, 85% of the GDR citizens were Protestants, while 10% were Catholics. In 1961, the renowned philosophical theologian Paul Tillich claimed that the Protestant population in East Germany had the most admirable Church in Protestantism, because the communists there had not been able to win a spiritual victory over them.[135] By 1989, membership in the Christian churches had dropped significantly. Protestants constituted 25% of the population, Catholics 5%. The share of people who considered themselves non-religious rose from 5% in 1950 to 70% in 1989.

When it first came to power, the Communist party asserted the compatibility of Christianity and Marxism–Leninism and sought Christian participation in the building of socialism. At first, the promotion of Marxist–Leninist atheism received little official attention. In the mid-1950s, as the Cold War heated up, atheism became a topic of major interest for the state, in both domestic and foreign contexts. University chairs and departments devoted to the study of scientific atheism were founded and much literature (scholarly and popular) on the subject was produced. This activity subsided in the late 1960s amid perceptions that it had started to become counterproductive. Official and scholarly attention to atheism renewed beginning in 1973, though this time with more emphasis on scholarship and on the training of cadres than on propaganda. Throughout, the attention paid to atheism in East Germany was never intended to jeopardise the cooperation that was desired from those East Germans who were religious.[136]

East Germany, historically, was majority Protestant (primarily Lutheran) from the early stages of the Protestant Reformation onwards. In 1948, freed from the influence of the Nazi-oriented German Christians, Lutheran, Reformed and United churches from most parts of Germany came together as the Protestant Church in Germany (Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland, EKD) at the Conference of Eisenach (Kirchenversammlung von Eisenach).

In 1969, the regional Protestant churches in East Germany and East Berlin[l] broke away from the EKD and formed the Federation of Protestant Churches in the German Democratic Republic (‹See Tfd›German: Bund der Evangelischen Kirchen in der DDR, BEK), in 1970 also joined by the Moravian Herrnhuter Brüdergemeinde. In June 1991, following the German reunification, the BEK churches again merged with the EKD ones.

Between 1956 and 1971, the leadership of the East German Lutheran churches gradually changed its relations with the state from hostility to cooperation.[137] From the founding of the GDR in 1949, the Socialist Unity Party sought to weaken the influence of the church on the rising generation. The church adopted an attitude of confrontation and distance toward the state. Around 1956 this began to develop into a more neutral stance accommodating conditional loyalty. The government was no longer regarded as illegitimate; instead, the church leaders started viewing the authorities as installed by God and, therefore, deserving of obedience by Christians. But on matters where the state demanded something which the churches felt was not in accordance with the will of God, the churches reserved their right to say no. There were both structural and intentional causes behind this development. Structural causes included the hardening of Cold War tensions in Europe in the mid-1950s, which made it clear that the East German state was not temporary. The loss of church members also made it clear to the leaders of the church that they had to come into some kind of dialogue with the state. The intentions behind the change of attitude varied from a traditional liberal Lutheran acceptance of secular power to a positive attitude toward socialist ideas.[138]

Manfred Stolpe became a lawyer for the Brandenburg Protestant Church in 1959 before taking up a position at church headquarters in Berlin. In 1969 he helped found the Bund der Evangelischen Kirchen in der DDR (BEK), where he negotiated with the government while at the same time working within the institutions of this Protestant body. He won the regional elections for the Brandenburg state assembly at the head of the SPD list in 1990. Stolpe remained in the Brandenburg government until he joined the federal government in 2002.

Apart from the Protestant state churches (‹See Tfd›German: Landeskirchen) united in the EKD/BEK and the Catholic Church there was a number of smaller Protestant bodies, including Protestant Free Churches (‹See Tfd›German: Evangelische Freikirchen) united in the Federation of the Free Protestant Churches in the German Democratic Republic and the Federation of the Free Protestant Churches in Germany, as well as the Free Lutheran Church, the Old Lutheran Church and Federation of the Reformed Churches in the German Democratic Republic. The Moravian Church also had its presence as the Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine. There were also other Protestants such as Methodists, Adventists, Mennonites and Quakers.

The smaller Catholic Church in eastern Germany had a fully functioning episcopal hierarchy in full accord with the Vatican. During the early postwar years, tensions were high. The Catholic Church as a whole (and particularly the bishops) resisted both the East German state and Marxist–Leninist ideology. The state allowed the bishops to lodge protests, which they did on issues such as abortion.[138]

After 1945, the Church did fairly well in integrating Catholic exiles from lands to the east (which mostly became part of Poland) and in adjusting its institutional structures to meet the needs of a church within an officially atheist society. This meant an increasingly hierarchical church structure, whereas in the area of religious education, press, and youth organisations, a system of temporary staff was developed, one that took into account the special situation of Caritas, a Catholic charity organisation. By 1950, therefore, there existed a Catholic subsociety that was well adjusted to prevailing specific conditions and capable of maintaining Catholic identity.[139][page needed]

With a generational change in the episcopacy taking place in the early 1980s, the state hoped for better relations with the new bishops, but the new bishops instead began holding unauthorised mass meetings, promoting international ties in discussions with theologians abroad, and hosting ecumenical conferences. The new bishops became less politically oriented and more involved in pastoral care and attention to spiritual concerns. The government responded by limiting international contacts for bishops.[140][need quotation to verify]

List of apostolic administrators:

About 600,000 children and youth were subordinate to East German residential child care system.

East Germany's culture was strongly influenced by communist thought and was marked by an attempt to define itself in opposition to the west, particularly West Germany and the United States. Critics of the East German state[who?] have claimed that the state's commitment to Communism was a hollow and cynical tool, Machiavellian in nature, but this assertion has been challenged by studies[which?] that have found that the East German leadership was genuinely committed to the advance of scientific knowledge, economic development, and social progress. However, Pence and Betts argue, the majority of East Germans over time increasingly regarded the state's ideals to be hollow, though there was also a substantial number of East Germans who regarded their culture as having a healthier, more authentic mentality than that of West Germany.[141]

GDR culture and politics were limited by the harsh censorship.[142] Compared to the music of the FRG, the freedom of art was less restricted by private-sector guidelines, but by guidelines from the state and the SED. Nevertheless, many musicians strove to explore the existing boundaries. Despite the state's support for music education, there were politically motivated conflicts with the state, especially among rock, blues and folk musicians and songwriters, as well as composers of so-called serious music.

A special feature of GDR culture is the broad spectrum of German rock bands. The Puhdys and Karat were some of the most popular mainstream bands in East Germany. Like most mainstream acts, they were members of the SED, appeared in state-run popular youth magazines such as Neues Leben and Magazin. Other popular rock bands were Wir, City, Silly and Pankow. Most of these artists recorded on the state-owned AMIGA label. All were required to open live performances and albums with the East German national anthem.[citation needed]

Schlager, which was very popular in the west, also gained a foothold early on in East Germany, and numerous musicians, such as Gerd Christian, Uwe Jensen, and Hartmut Schulze-Gerlach gained national fame. From 1962 to 1976, an international schlager festival was held in Rostock, garnering participants from between 18 and 22 countries each year.[143] The city of Dresden held a similar international festival for schlager musicians from 1971 until shortly before reunification.[144] There was a national schlager contest hosted yearly in Magdeburg from 1966 to 1971 as well.[145]

Bands and singers from other socialist countries were popular, e.g. Czerwone Gitary from Poland known as the Rote Gitarren.[146][147] Czech Karel Gott, the Golden Voice from Prague, was beloved in both German states.[148] Hungarian band Omega performed in both German states, and Yugoslavian band Korni Grupa toured East Germany in the 1970s.[149][150]

West German television and radio could be received in many parts of the East. The Western influence led to the formation of more "underground" groups with a decisively western-oriented sound. A few of these bands – the so-called Die anderen Bands ("the other bands") – were Die Skeptiker, Die Art and Feeling B. Additionally, hip hop culture reached the ears of the East German youth. With videos such as Beat Street and Wild Style, young East Germans were able to develop a hip hop culture of their own.[151] East Germans accepted hip hop as more than just a music form. The entire street culture surrounding rap entered the region and became an outlet for oppressed youth.[152]

The government of the GDR was invested in both promoting the tradition of German classical music, and in supporting composers to write new works in that tradition. Notable East German composers include Hanns Eisler, Paul Dessau, Ernst Hermann Meyer, Rudolf Wagner-Régeny, and Kurt Schwaen.

The birthplace of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), Eisenach, was rendered as a museum about him, featuring more than three hundred instruments, which, in 1980, received some 70,000 visitors. In Leipzig, the Bach archive contains his compositions and correspondence and recordings of his music.[153]