Константинополь [a] (см. другие названия) стал столицей Римской империи во время правления Константина Великого в 330 году. После распада Западной Римской империи в конце V века Константинополь остался столицей Восточной Римской империи (также известной как Византийская империя ; 330–1204 и 1261–1453), Латинской империи (1204–1261) и Османской империи (1453–1922). После турецкой войны за независимость турецкая столица переехала в Анкару . Официально переименованный в Стамбул в 1930 году, город сегодня является вторым по величине городом в Европе , расположенным по обе стороны пролива Босфор и лежащим как в Европе , так и в Азии , а также финансовым центром Турции .

В 324 году, после воссоединения Западной и Восточной Римских империй, древний город Византий был выбран в качестве новой столицы Римской империи, и город был переименован в Нова Рома, или «Новый Рим», императором Константином Великим . 11 мая 330 года он был переименован в Константинополь и посвящен Константину. [6] Константинополь обычно считается центром и «колыбелью православной христианской цивилизации ». [7] [8] С середины V века до начала XIII века Константинополь был крупнейшим и богатейшим городом в Европе. [9] Город прославился своими архитектурными шедеврами, такими как Собор Святой Софии , собор Восточной православной церкви , который служил резиденцией Вселенского патриархата ; священный Императорский дворец , где жили императоры; Ипподром ; Золотые ворота сухопутных стен; и роскошные аристократические дворцы. Константинопольский университет был основан в V веке и хранил художественные и литературные сокровища до своего разграбления в 1204 и 1453 годах [10] , включая его огромную Императорскую библиотеку , которая содержала остатки Александрийской библиотеки и насчитывала 100 000 томов. [11] Город был резиденцией Вселенского Патриарха Константинопольского и хранителем самых святых реликвий христианского мира , таких как Терновый венец и Животворящий Крест .

Константинополь славился своими массивными и сложными укреплениями, которые считались одними из самых сложных оборонительных архитектур античности . Феодосиевы стены состояли из двойной стены, лежащей примерно в 2 километрах (1,2 мили) к западу от первой стены, и рва с частоколом впереди. [12] Расположение Константинополя между Золотым Рогом и Мраморным морем уменьшало площадь земли, которая нуждалась в оборонительных стенах. Город был построен намеренно, чтобы соперничать с Римом , и утверждалось, что несколько возвышенностей внутри его стен соответствовали «семи холмам» Рима. [13] Неприступная оборона окружала великолепные дворцы, купола и башни, результат процветания Константинополя, достигнутого в качестве ворот между двумя континентами ( Европой и Азией ) и двумя морями (Средиземным и Черным морем). Хотя Константинополь неоднократно подвергался осаде различными армиями, оборона Константинополя оставалась непроницаемой на протяжении почти девятисот лет.

Однако в 1204 году войска Четвертого крестового похода захватили и опустошили город, и в течение нескольких десятилетий его жители жили под латинской оккупацией в уменьшающемся и обезлюдевшем городе. В 1261 году византийский император Михаил VIII Палеолог освободил город, и после реставрации при династии Палеологов он частично восстановился. С приходом Османской империи в 1299 году Византийская империя начала терять территории, а город начал терять население. К началу 15 века Византийская империя сократилась до Константинополя и его окрестностей, а также Мореи в Греции, что сделало его анклавом внутри Османской империи. Город был окончательно осажден и завоеван Османской империей в 1453 году, оставаясь под ее контролем до начала 20 века, после чего он был переименован в Стамбул в государстве-преемнике империи , Турции.

Согласно Плинию Старшему в его «Естественной истории» , первое известное название поселения на месте Константинополя было Лигос [14], поселение , вероятно, фракийского происхождения, основанное между XIII и XI веками до нашей эры. [15] Это место, согласно мифу об основании города, было заброшено к тому времени, когда греческие поселенцы из города-государства Мегара основали Византию ( древнегреческий : Βυζάντιον , Byzántion ) около 657 года до нашей эры, [16] напротив города Халкидон на азиатской стороне Босфора.

Происхождение названия Византион , более известного позже под латинским названием Византий , не совсем ясно, хотя некоторые предполагают, что оно имеет фракийское происхождение. [17] [18] В мифе об основании города говорится, что поселение было названо в честь лидера мегарских колонистов, Визаса . Сами поздние византийцы Константинополя утверждали, что город был назван в честь двух людей, Визаса и Антеса, хотя это, скорее всего, была просто игра слов Византион . [19]

Город был ненадолго переименован в Августу Антонину в начале III века н. э. императором Септимием Севером (193–211), который в 196 году сравнял город с землей за поддержку соперника в гражданской войне и перестроил его в честь своего сына Марка Аврелия Антонина (который стал его преемником на посту императора), широко известного как Каракалла . [19] [20] Название, по-видимому, было быстро забыто и заброшено, и город вернулся к Византию/Византиону либо после убийства Каракаллы в 217 году, либо, самое позднее, после падения династии Северов в 235 году.

Византия взяла название Константинополь ( греч . Κωνσταντινούπολις, романизированное : Kōnstantinoupolis; «город Константина») после своего переоснования при римском императоре Константине I , который перенес столицу Римской империи в Византию в 330 году и официально обозначил свою новую столицу как Nova Roma ( Νέα Ῥώμη ) «Новый Рим». В это время город также называли «Вторым Римом», «Восточным Римом» и Roma Constantinopolitana ( лат. «Константинопольский Рим»). [18] Поскольку город стал единственной оставшейся столицей Римской империи после падения Запада, а его богатство, население и влияние росли, у города также появилось множество прозвищ.

Будучи крупнейшим и богатейшим городом Европы в IV–XIII веках, а также центром культуры и образования Средиземноморского бассейна, Константинополь стал известен под такими престижными титулами, как Базилевуса (Королева городов) и Мегаполис (Великий город), а в разговорной речи константинопольцы и провинциальные византийцы обычно называли его просто Полис ( ἡ Πόλις ) «Город». [21]

На языке других народов Константинополь упоминался так же благоговейно. Средневековые викинги, которые имели контакты с империей через свою экспансию в Восточной Европе ( варяги ), использовали древнескандинавское название Miklagarðr (от mikill 'большой' и garðr 'город'), а позднее Miklagard и Miklagarth . [19] На арабском языке город иногда назывался Rūmiyyat al-Kubra (Великий город римлян), а на персидском — Takht-e Rum (Трон римлян).

В восточнославянских и южнославянских языках, в том числе в Киевской Руси , Константинополь назывался Царьград ( Царьград ) или Carigrad , «Город кесаря (императора)», от славянских слов tsar («кесарь» или «король») и grad («город»). Вероятно, это была калька с греческой фразы, такой как Βασιλέως Πόλις ( Vasileos Polis ), «город императора [царя]».

На персидском языке город также назывался Аситане (Порог государства), а на армянском — Госдантнуболис (Город Константина). [22]

Современное турецкое название города, Стамбул , происходит от греческой фразы eis tin Polin ( εἰς τὴν πόλιν ), что означает «(в)городе». [19] [23] Это название использовалось в разговорной речи на турецком языке наряду с Kostantiniyye , более формальной адаптацией оригинального Константинополя , в период османского владычества, в то время как западные языки в основном продолжали называть город Константинополем до начала 20-го века. В 1928 году турецкий алфавит был изменен с арабского на латинский. После этого, в рамках движения по тюркизации , Турция начала призывать другие страны использовать турецкие названия для турецких городов , вместо других транслитераций на латинский шрифт, которые использовались во времена Османской империи, и город стал известен как Стамбул и его вариации на большинстве мировых языков. [24] [25] [26] [27]

Название Константинополь до сих пор используется членами Восточной Православной Церкви в титуле одного из своих важнейших лидеров, православного патриарха, находящегося в городе, именуемого «Его Божественнейшее Всесвятейшество Архиепископ Константинополя Нового Рима и Вселенский Патриарх». В Греции сегодня город до сих пор называется Константиноуполис(ы) ( Κωνσταντινούπολις/Κωνσταντινούπολη ) или просто «Город» ( Η Πόλη ).

Константинополь был основан римским императором Константином I (272–337) в 324 году [6] на месте уже существующего города Византий , который был заселен в первые дни греческой колониальной экспансии , около 657 года до н. э., колонистами города-государства Мегара . Это первое крупное поселение, которое возникло на месте более позднего Константинополя, но первым известным поселением был Лигос , упомянутый в «Естественных историях» Плиния. [28] Помимо этого, об этом первоначальном поселении мало что известно. Согласно мифу об основании города, это место было заброшено к тому времени, когда греческие поселенцы из города-государства Мегара основали Византий ( Βυζάντιον ) около 657 года до н. э., [20] напротив города Халкидон на азиатской стороне Босфора.

Гесихий Милетский писал, что некоторые «утверждают, что люди из Мегары, которые вели свое происхождение от Нисоса, приплыли в это место под предводительством своего вождя Визаса, и выдумывают басню, что его имя было связано с городом». Некоторые версии мифа об основании говорят, что Визас был сыном местной нимфы , в то время как другие говорят, что он был зачат одной из дочерей Зевса и Посейдоном . Гесихий также приводит альтернативные версии легенды об основании города, которые он приписывает древним поэтам и писателям: [29]

Говорят, что первые аргивяне, получив это пророчество от Пифии: «

Блаженны те, кто будет населять этот священный город,

узкую полоску фракийского берега у устья Понта,

где два щенка пьют серое море,

где рыба и олень пасутся на одном пастбище»,

— построили свои жилища в том месте, где реки Кидарос и Барбис имеют свои устья, одна течет с севера, другая с запада и сливается с морем у алтаря нимфы по имени Семестра».

Город сохранял независимость как город-государство, пока не был присоединен Дарием I в 512 г. до н. э. к Персидской империи , который видел в этом месте оптимальное место для строительства понтонного моста, ведущего в Европу, поскольку Византия находилась в самом узком месте пролива Босфор. Персидское правление продолжалось до 478 г. до н. э., когда в рамках греческого контрнаступления на Второе персидское вторжение в Грецию греческая армия под предводительством спартанского полководца Павсания захватила город, который оставался независимым, но подчиненным городом под властью афинян, а затем спартанцев после 411 г. до н. э. [30] Дальновидный договор с зарождающейся властью Рима в 150 г. до н. э. , который предусматривал дань в обмен на независимый статус, позволил ему войти в римское правление невредимым. [31] Этот договор принес бы дивиденды в ретроспективе, поскольку Византия сохранила бы этот независимый статус и процветала бы в условиях мира и стабильности в Pax Romana на протяжении почти трех столетий до конца II века н.э. [32]

Византия никогда не была крупным влиятельным городом-государством, как Афины , Коринф или Спарта , но город наслаждался относительным миром и устойчивым ростом как процветающий торговый город, обусловленный его замечательным положением. Место лежало по обе стороны сухопутного пути из Европы в Азию и морского пути из Черного моря в Средиземное , и имело в Золотом Роге прекрасную и просторную гавань. Уже тогда, в греческие и ранние римские времена, Византия славилась стратегическим географическим положением, которое затрудняло ее осаду и захват, а ее положение на перекрестке азиатско-европейского торгового пути по суше и как ворот между Средиземным и Черным морями делало ее слишком ценным поселением, чтобы его покидать, как позже понял император Септимий Север, когда он сравнял город с землей за поддержку притязаний Песценния Нигера . [33] Этот шаг подвергся резкой критике со стороны современного ему консула и историка Кассия Диона , который сказал, что Север уничтожил «сильный римский форпост и базу для операций против варваров из Понта и Азии». [34] Позже, ближе к концу своего правления, он восстановил Византий, в котором он был ненадолго переименован в Августу Антонину , укрепив его новой городской стеной своего имени — Северовой стеной.

Константин имел в целом более красочные планы. Восстановив единство Империи и находясь в процессе крупных правительственных реформ, а также спонсируя консолидацию христианской церкви , он прекрасно понимал, что Рим был неудовлетворительной столицей. Рим был слишком далеко от границ, а значит, от армий и императорских дворов, и он предлагал нежелательную игровую площадку для недовольных политиков. Тем не менее, он был столицей государства более тысячи лет, и могло показаться немыслимым предложить перенести столицу в другое место. Тем не менее, Константин определил место Византия как правильное место: место, где император мог сидеть, легко защищаемый, с легким доступом к границам Дуная или Евфрата , его двор снабжался из богатых садов и сложных мастерских Римской Азии, его сокровищницы наполнялись самыми богатыми провинциями Империи. [35]

Константинополь строился в течение шести лет и был освящен 11 мая 330 года. [6] [36] Константин разделил расширенный город, как и Рим, на 14 районов и украсил его общественными работами, достойными императорской метрополии. [37] Однако поначалу новый Рим Константина не обладал всеми достоинствами старого Рима. Он обладал проконсулом , а не городским префектом . В нем не было преторов , трибунов или квесторов . Хотя в нем были сенаторы, они носили титул clarus , а не clarissimus , как в Риме. В нем также не было множества других административных должностей, регулирующих снабжение продовольствием, полицию, статуи, храмы, канализацию, акведуки или другие общественные работы. Новая программа строительства была выполнена в большой спешке: колонны, мрамор, двери и плитка были оптом взяты из храмов империи и перенесены в новый город. Подобным образом, многие из величайших произведений греческого и римского искусства вскоре можно было увидеть на его площадях и улицах. Император стимулировал частное строительство, обещая домовладельцам дары земли из императорских поместий в Азии и Понтике , а 18 мая 332 года он объявил, что, как и в Риме, гражданам будут раздаваться бесплатные продукты питания. В то время, как говорят, сумма составляла 80 000 пайков в день, которые выдавались из 117 распределительных пунктов по всему городу. [38]

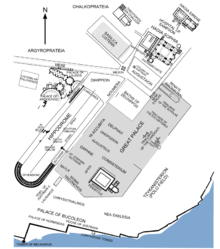

Константин разбил новую площадь в центре старого Византия, назвав ее Августеум . Новое здание сената (или курия) располагалось в базилике на восточной стороне. На южной стороне большой площади был возведен Большой дворец императора с его внушительным входом, Халкой , и его церемониальными покоями, известными как Дворец Дафны . Рядом находился огромный ипподром для гонок на колесницах, вмещавший более 80 000 зрителей, и знаменитые термы Зевксиппа . У западного входа в Августеум находился Милион , сводчатый памятник, от которого измерялись расстояния по всей Восточной Римской империи.

От Августеума вела большая улица Меса , выложенная колоннадами. Когда она спускалась с Первого холма города и поднималась на Второй холм, она проходила слева мимо Претория или суда. Затем она проходила через овальный Форум Константина , где располагалось второе здание Сената и высокая колонна со статуей самого Константина в облике Гелиоса , увенчанного нимбом из семи лучей и смотрящего на восходящее солнце. Оттуда Меса проходила дальше и через Форум Таури , а затем через Форум Бовис и, наконец, вверх по Седьмому холму (или Ксеролофу) и через Золотые ворота в Стене Константина . После строительства Стен Феодосия в начале V века она была продлена до новых Золотых ворот , достигнув общей длины в семь римских миль . [39] После возведения Феодосиевых стен Константинополь занимал территорию, примерно равную площади Древнего Рима внутри Аврелиановых стен, или около 1400 га. [40]

Значение Константинополя росло, но постепенно. Со смерти Константина в 337 году до восшествия на престол Феодосия I императоры жили в нем только в 337–338, 347–351, 358–361, 368–369 годах. Его статус столицы был признан назначением первого известного городского префекта города Гонората, который занимал эту должность с 11 декабря 359 года по 361 год. Городские префекты имели параллельную юрисдикцию над тремя провинциями каждая в соседних епархиях Фракии (в которой находился город), Понта и Азии, сопоставимую с 100-мильной чрезвычайной юрисдикцией префекта Рима. Император Валент , который ненавидел город и провел там всего один год, тем не менее построил дворец Гебдомон на берегу Пропонтиды около Золотых ворот , вероятно, для использования при смотре войск. Все императоры вплоть до Зенона и Василиска короновались и провозглашались на Гебдомоне. Феодосий I основал церковь Иоанна Крестителя, чтобы разместить череп святого (сегодня он хранится во дворце Топкапы ), установил себе мемориальную колонну на Форуме Тавра и превратил разрушенный храм Афродиты в каретный сарай для префекта претория ; Аркадий построил новый форум, названный в его честь, на Месе, недалеко от стен Константина.

После шока от битвы при Адрианополе в 378 году, в которой Валент и цвет римской армии были уничтожены вестготами в течение нескольких дней пути, город занялся своей обороной, и в 413–414 годах Феодосий II построил 18-метровые (60 футов) тройные крепостные стены , которые не могли быть разрушены до появления пороха. Феодосий также основал университет около Форума Тавра 27 февраля 425 года.

Улдин , принц гуннов , появился на Дунае примерно в это время и двинулся во Фракию, но его покинули многие из его последователей, которые присоединились к римлянам, чтобы оттеснить их короля к северу от реки. После этого были построены новые стены для защиты города, а флот на Дунае улучшился.

После того, как варвары захватили Западную Римскую империю, Константинополь стал бесспорной столицей Римской империи. Императоры больше не странствовали между различными столицами дворов и дворцами. Они оставались в своих дворцах в Великом городе и отправляли генералов командовать своими армиями. Богатства восточного Средиземноморья и западной Азии текли в Константинополь.

_by_Florentine_cartographer_Cristoforo_Buondelmonte.jpg/440px-Map_of_Constantinople_(1422)_by_Florentine_cartographer_Cristoforo_Buondelmonte.jpg)

Император Юстиниан I (527–565) был известен своими успехами в войне, своими правовыми реформами и своими общественными работами. Именно из Константинополя его экспедиция для отвоевания бывшей епархии Африки отплыла около 21 июня 533 года. Перед их отплытием корабль командующего Велизария был пришвартован перед императорским дворцом, и Патриарх вознес молитвы за успех предприятия. После победы в 534 году сокровища Иерусалимского храма , разграбленные римлянами в 70 году н. э. и увезенные в Карфаген вандалами после разграбления Рима в 455 году, были доставлены в Константинополь и хранились в течение некоторого времени, возможно, в церкви Святого Полиевкта , прежде чем были возвращены в Иерусалим либо в церковь Воскресения , либо в Новую церковь. [42]

Гонки на колесницах были важны в Риме на протяжении столетий. В Константинополе ипподром со временем стал все более важным местом политического значения. Это было место, где (как тень народных выборов старого Рима) люди посредством аккламации демонстрировали свое одобрение новому императору, а также где они открыто критиковали правительство или требовали смещения непопулярных министров. Он играл решающую роль во время беспорядков и во времена политических волнений. Ипподром предоставлял место для того, чтобы толпа могла получить положительный ответ или где аплодисменты толпы были подорваны, прибегнув к беспорядкам, которые последовали в последующие годы. [43] Во времена Юстиниана общественный порядок в Константинополе стал критически важным политическим вопросом.

На протяжении позднеримского и раннего византийского периодов христианство решало фундаментальные вопросы идентичности, и спор между ортодоксами и монофизитами стал причиной серьезных беспорядков, выраженных в преданности партиям колесничных гонок Синих и Зеленых. Сторонники Синих и Зеленых, как говорили [44], носили нестриженные волосы на лице, брили волосы на голове спереди и отращивали их сзади, носили туники с широкими рукавами, обтягивающие запястья; и формировали банды для участия в ночных грабежах и уличном насилии. Наконец, эти беспорядки приняли форму крупного восстания 532 года, известного как беспорядки «Ника» (от боевого клича «Побеждай!» участников). [45] Бунты «Ника» начались на ипподроме и закончились там натиском более 30 000 человек, согласно Прокопию, тех, кто был в синих и зеленых фракциях, невинных и виновных. Это замкнуло круг взаимоотношений на Ипподроме между властью и народом во времена Юстиниана. [43]

Пожары, устроенные мятежниками «Ники», уничтожили Феодосиеву базилику Святой Софии (Святой Мудрости), городской собор, который находился к северу от Августеума и сам заменил Константинову базилику, основанную Констанцием II, чтобы заменить первый византийский собор, Айя Ирины (Святого Мира). Юстиниан поручил Анфимию Траллскому и Исидору Милетскому заменить ее новой и несравненной Айя Софией . Это был великий собор города, купол которого, как говорили, поддерживался только Богом, и который был напрямую связан с дворцом, так что императорская семья могла посещать службы, не проходя по улицам. «Архитектурная форма здания должна была отражать программную гармонию Юстиниана: круглый купол (символ светской власти в классической римской архитектуре) гармонично сочетался с прямоугольной формой (типичной для христианских и дохристианских храмов)». [46] Освящение состоялось 26 декабря 537 года в присутствии императора, который, как позже сообщалось, воскликнул: «О Соломон , я превзошел тебя!» [47] В соборе Святой Софии служило 600 человек, включая 80 священников, а его строительство обошлось в 20 000 фунтов золота. [48]

Юстиниан также приказал Антемию и Исидору снести и заменить первоначальную церковь Святых Апостолов и Айя Ирины, построенную Константином, новыми церквями с тем же посвящением. Юстиниановская церковь Святых Апостолов была спроектирована в форме равностороннего креста с пятью куполами и украшена прекрасной мозаикой. Эта церковь должна была оставаться местом захоронения императоров, начиная с самого Константина, до 11 века. Когда город пал под натиском турок в 1453 году, церковь была снесена, чтобы освободить место для гробницы Мехмеда II Завоевателя. Юстиниан также беспокоился о других аспектах городской застройки, приняв законы против злоупотребления законами, запрещающими строительство в пределах 100 футов (30 м) от набережной, чтобы защитить вид. [49]

Во время правления Юстиниана I население города достигло около 500 000 человек. [50] Однако социальная структура Константинополя также была повреждена наступлением чумы Юстиниана между 541 и 542 годами нашей эры. Она убила, возможно, 40% жителей города. [51]

В начале VII века авары , а позже булгары захватили большую часть Балкан , угрожая Константинополю нападением с запада. Одновременно персидские Сасаниды захватили Префектуру Востока и проникли глубоко в Анатолию . Ираклий , сын экзарха Африки , отплыл в город и занял трон. Он нашел военную ситуацию настолько ужасной, что, как говорят, подумывал о переносе имперской столицы в Карфаген, но смягчился после того, как жители Константинополя умоляли его остаться. Граждане потеряли право на бесплатное зерно в 618 году, когда Ираклий понял, что город больше не может снабжаться из Египта из-за персидских войн: в результате этого население существенно сократилось. [52]

В то время как город выдержал осаду Сасанидов и аваров в 626 году, Ираклий провел кампанию вглубь персидской территории и ненадолго восстановил статус-кво в 628 году, когда персы сдали все свои завоевания. Однако за арабскими завоеваниями последовали дальнейшие осады , сначала с 674 по 678 год , а затем с 717 по 718 год . Феодосиевы стены сделали город непроницаемым с суши, в то время как недавно обнаруженное зажигательное вещество, известное как греческий огонь, позволило византийскому флоту уничтожить арабский флот и обеспечить снабжение города. Во второй осаде решающую помощь оказал второй правитель Болгарии , хан Тервел . Его называли Спасителем Европы . [53]

В 730-х годах Лев III провел масштабный ремонт стен Феодосия, которые были повреждены частыми и жестокими нападениями; эти работы финансировались за счет специального налога со всех подданных империи. [54]

Феодора, вдова императора Феофила (умерла в 842 г.), исполняла обязанности регента во время несовершеннолетия своего сына Михаила III , который, как говорят, был приобщен к распутным привычкам своим братом Вардасом. Когда Михаил пришел к власти в 856 г., он стал известен чрезмерным пьянством, появлялся на ипподроме в качестве возницы и пародировал религиозные процессии духовенства. Он удалил Феодору из Большого дворца в Карийский дворец, а затем в монастырь Гастрия , но после смерти Вардаса она была отпущена жить во дворец Святого Маманта; у нее также была загородная резиденция в Антемианском дворце, где Михаил был убит в 867 г. [55]

В 860 году на город напало новое княжество, основанное несколькими годами ранее в Киеве Аскольдом и Диром , двумя варяжскими вождями: двести небольших судов прошли через Босфор и разграбили монастыри и другие владения на пригородных Принцевых островах . Орифас , адмирал византийского флота, предупредил императора Михаила, который быстро обратил захватчиков в бегство; но внезапность и дикость нападения произвели глубокое впечатление на граждан. [56]

In 980, the emperor Basil II received an unusual gift from Prince Vladimir of Kiev: 6,000 Varangian warriors, which Basil formed into a new bodyguard known as the Varangian Guard. They were known for their ferocity, honour, and loyalty. It is said that, in 1038, they were dispersed in winter quarters in the Thracesian Theme when one of their number attempted to violate a countrywoman, but in the struggle she seized his sword and killed him; instead of taking revenge, however, his comrades applauded her conduct, compensated her with all his possessions, and exposed his body without burial as if he had committed suicide.[57] However, following the death of an Emperor, they became known also for plunder in the Imperial palaces.[58] Later in the 11th century the Varangian Guard became dominated by Anglo-Saxons who preferred this way of life to subjugation by the new Norman kings of England.[59]

The Book of the Eparch, which dates to the 10th century, gives a detailed picture of the city's commercial life and its organization at that time. The corporations in which the tradesmen of Constantinople were organised were supervised by the Eparch, who regulated such matters as production, prices, import, and export. Each guild had its own monopoly, and tradesmen might not belong to more than one. It is an impressive testament to the strength of tradition how little these arrangements had changed since the office, then known by the Latin version of its title, had been set up in 330 to mirror the urban prefecture of Rome.[61]

In the 9th and 10th centuries, Constantinople had a population of between 500,000 and 800,000.[62]

In the 8th and 9th centuries, the iconoclast movement caused serious political unrest throughout the Empire. The emperor Leo III issued a decree in 726 against images, and ordered the destruction of a statue of Christ over one of the doors of the Chalke, an act that was fiercely resisted by the citizens.[63] Constantine V convoked a church council in 754, which condemned the worship of images, after which many treasures were broken, burned, or painted over with depictions of trees, birds or animals: One source refers to the church of the Holy Virgin at Blachernae as having been transformed into a "fruit store and aviary".[64] Following the death of her husband Leo IV in 780, the empress Irene restored the veneration of images through the agency of the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.

The iconoclast controversy returned in the early 9th century, only to be resolved once more in 843 during the regency of Empress Theodora, who restored the icons. These controversies contributed to the deterioration of relations between the Western and the Eastern Churches.

In the late 11th century catastrophe struck with the unexpected and calamitous defeat of the imperial armies at the Battle of Manzikert in Armenia in 1071. The Emperor Romanus Diogenes was captured. The peace terms demanded by Alp Arslan, sultan of the Seljuk Turks, were not excessive, and Romanus accepted them. On his release, however, Romanus found that enemies had placed their own candidate on the throne in his absence; he surrendered to them and suffered death by torture, and the new ruler, Michael VII Ducas, refused to honour the treaty. In response, the Turks began to move into Anatolia in 1073. The collapse of the old defensive system meant that they met no opposition, and the empire's resources were distracted and squandered in a series of civil wars. Thousands of Turkoman tribesmen crossed the unguarded frontier and moved into Anatolia. By 1080, a huge area had been lost to the Empire, and the Turks were within striking distance of Constantinople.

Under the Komnenian dynasty (1081–1185), Byzantium staged a remarkable recovery. In 1090–91, the nomadic Pechenegs reached the walls of Constantinople, where Emperor Alexius I with the aid of the Kipchaks annihilated their army.[66] In response to a call for aid from Alexius, the First Crusade assembled at Constantinople in 1096, but declining to put itself under Byzantine command set out for Jerusalem on its own account.[67] John II built the monastery of the Pantocrator (Almighty) with a hospital for the poor of 50 beds.[68]

With the restoration of firm central government, the empire became fabulously wealthy. The population was rising (estimates for Constantinople in the 12th century vary from some 100,000 to 500,000), and towns and cities across the realm flourished. Meanwhile, the volume of money in circulation dramatically increased. This was reflected in Constantinople by the construction of the Blachernae palace, the creation of brilliant new works of art, and general prosperity at this time: an increase in trade, made possible by the growth of the Italian city-states, may have helped the growth of the economy. It is certain that the Venetians and others were active traders in Constantinople, making a living out of shipping goods between the Crusader Kingdoms of Outremer and the West, while also trading extensively with Byzantium and Egypt. The Venetians had factories on the north side of the Golden Horn, and large numbers of westerners were present in the city throughout the 12th century. Toward the end of Manuel I Komnenos's reign, the number of foreigners in the city reached about 60,000–80,000 people out of a total population of about 400,000 people.[69] In 1171, Constantinople also contained a small community of 2,500 Jews.[70] In 1182, most Latin (Western European) inhabitants of Constantinople were massacred.[71]

In artistic terms, the 12th century was a very productive period. There was a revival in the mosaic art, for example: Mosaics became more realistic and vivid, with an increased emphasis on depicting three-dimensional forms. There was an increased demand for art, with more people having access to the necessary wealth to commission and pay for such work.

On 25 July 1197, Constantinople was struck by a severe fire which burned the Latin Quarter and the area around the Gate of the Droungarios (Turkish: Odun Kapısı) on the Golden Horn.[72][73] Nevertheless, the destruction wrought by the 1197 fire paled in comparison with that brought by the Crusaders. In the course of a plot between Philip of Swabia, Boniface of Montferrat and the Doge of Venice, the Fourth Crusade was, despite papal excommunication, diverted in 1203 against Constantinople, ostensibly promoting the claims of Alexios IV Angelos brother-in-law of Philip, son of the deposed emperor Isaac II Angelos. The reigning emperor Alexios III Angelos had made no preparation. The Crusaders occupied Galata, broke the defensive chain protecting the Golden Horn, and entered the harbour, where on 27 July they breached the sea walls: Alexios III fled. But the new Alexios IV Angelos found the Treasury inadequate, and was unable to make good the rewards he had promised to his western allies. Tension between the citizens and the Latin soldiers increased. In January 1204, the protovestiarius Alexios Murzuphlos provoked a riot, it is presumed, to intimidate Alexios IV, but whose only result was the destruction of the great statue of Athena Promachos, the work of Phidias, which stood in the principal forum facing west.

In February 1204, the people rose again: Alexios IV was imprisoned and executed, and Murzuphlos took the purple as Alexios V Doukas. He made some attempt to repair the walls and organise the citizenry, but there had been no opportunity to bring in troops from the provinces and the guards were demoralised by the revolution. An attack by the Crusaders on 6 April failed, but a second from the Golden Horn on 12 April succeeded, and the invaders poured in. Alexios V fled. The Senate met in Hagia Sophia and offered the crown to Theodore Lascaris, who had married into the Angelos dynasty, but it was too late. He came out with the Patriarch to the Golden Milestone before the Great Palace and addressed the Varangian Guard. Then the two of them slipped away with many of the nobility and embarked for Asia. By the next day the Doge and the leading Franks were installed in the Great Palace, and the city was given over to pillage for three days.

Sir Steven Runciman, historian of the Crusades, wrote that the sack of Constantinople is "unparalleled in history".

For nine centuries, [...] the great city had been the capital of Christian civilization. It was filled with works of art that had survived from ancient Greece and with the masterpieces of its own exquisite craftsmen. The Venetians [...] seized treasures and carried them off to adorn [...] their town. But the Frenchmen and Flemings were filled with a lust for destruction. They rushed in a howling mob down the streets and through the houses, snatching up everything that glittered and destroying whatever they could not carry, pausing only to murder or to rape, or to break open the wine-cellars [...] . Neither monasteries nor churches nor libraries were spared. In Hagia Sophia itself, drunken soldiers could be seen tearing down the silken hangings and pulling the great silver iconostasis to pieces, while sacred books and icons were trampled under foot. While they drank merrily from the altar-vessels a prostitute set herself on the Patriarch's throne and began to sing a ribald French song. Nuns were ravished in their convents. Palaces and hovels alike were entered and wrecked. Wounded women and children lay dying in the streets. For three days the ghastly scenes [...] continued, till the huge and beautiful city was a shambles. [...] When [...] order was restored, [...] citizens were tortured to make them reveal the goods that they had contrived to hide.[74]

For the next half-century, Constantinople was the seat of the Latin Empire. Under the rulers of the Latin Empire, the city declined, both in population and the condition of its buildings. Alice-Mary Talbot cites an estimated population for Constantinople of 400,000 inhabitants; after the destruction wrought by the Crusaders on the city, about one third were homeless, and numerous courtiers, nobility, and higher clergy, followed various leading personages into exile. "As a result Constantinople became seriously depopulated," Talbot concludes.[75]

The Latins took over at least 20 churches and 13 monasteries, most prominently the Hagia Sophia, which became the cathedral of the Latin Patriarch of Constantinople. It is to these that E.H. Swift attributed the construction of a series of flying buttresses to shore up the walls of the church, which had been weakened over the centuries by earthquake tremors.[76] However, this act of maintenance is an exception: for the most part, the Latin occupiers were too few to maintain all of the buildings, either secular and sacred, and many became targets for vandalism or dismantling. Bronze and lead were removed from the roofs of abandoned buildings and melted down and sold to provide money to the chronically under-funded Empire for defense and to support the court; Deno John Geanokoplos writes that "it may well be that a division is suggested here: Latin laymen stripped secular buildings, ecclesiastics, the churches."[77] Buildings were not the only targets of officials looking to raise funds for the impoverished Latin Empire: the monumental sculptures which adorned the Hippodrome and fora of the city were pulled down and melted for coinage. "Among the masterpieces destroyed, writes Talbot, "were a Herakles attributed to the fourth-century B.C. sculptor Lysippos, and monumental figures of Hera, Paris, and Helen."[78]

The Nicaean emperor John III Vatatzes reportedly saved several churches from being dismantled for their valuable building materials; by sending money to the Latins "to buy them off" (exonesamenos), he prevented the destruction of several churches.[79] According to Talbot, these included the churches of Blachernae, Rouphinianai, and St. Michael at Anaplous. He also granted funds for the restoration of the Church of the Holy Apostles, which had been seriously damaged in an earthquake.[78]

_by_Jean_Le_Tavernier_after_1455.jpg/440px-Le_siège_de_Constantinople_(1453)_by_Jean_Le_Tavernier_after_1455.jpg)

The Byzantine nobility scattered, many going to Nicaea, where Theodore Lascaris set up an imperial court, or to Epirus, where Theodore Angelus did the same; others fled to Trebizond, where one of the Comneni had already with Georgian support established an independent seat of empire.[80] Nicaea and Epirus both vied for the imperial title, and tried to recover Constantinople. In 1261, Constantinople was captured from its last Latin ruler, Baldwin II, by the forces of the Nicaean emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos under the command of Caesar Alexios Strategopoulos.

Although Constantinople was retaken by Michael VIII Palaiologos, the Empire had lost many of its key economic resources, and struggled to survive. The palace of Blachernae in the north-west of the city became the main Imperial residence, with the old Great Palace on the shores of the Bosporus going into decline. When Michael VIII captured the city, its population was 35,000 people, but, by the end of his reign, he had succeeded in increasing the population to about 70,000 people.[81] The Emperor achieved this by summoning former residents who had fled the city when the crusaders captured it, and by relocating Greeks from the recently reconquered Peloponnese to the capital.[82] Military defeats, civil wars, earthquakes and natural disasters were joined by the Black Death, which in 1347 spread to Constantinople, exacerbated the people's sense that they were doomed by God.[83][84]

Castilian traveler and writer Ruy González de Clavijo, who saw Constantinople in 1403, wrote that the area within the city walls included small neighborhoods separated by orchards and fields. The ruins of palaces and churches could be seen everywhere. The aqueducts and the most densely inhabited neighborhoods were along the coast of the Marmara Sea and Golden Horn. Only the coastal areas, in particular the commercial areas facing the Golden Horn, had a dense population. Although the Genoese colony in Galata was small, it was overcrowded and had magnificent mansions.[85]

By May 1453, the city no longer possessed the treasure troves of Aladdin that the Ottoman troops longingly imagined as they stared up at the walls. Gennadios Scholarios, Patriarch of Constantinople from 1454 to 1464, was saying that the capital of the Empire, that was once the "city of wisdom", became "the city of ruins".[86]

When the Ottoman Turks captured the city (1453) it contained approximately 50,000 people.[87] Tedaldi of Florence estimated the population at 30,000 to 36,000, while in Chronica Vicentina, the Italian Andrei di Arnaldo estimated it at 50,000. The plague epidemic of 1435 must have caused the population to drop.[85]

The population decline also had a huge impact upon the Constantinople's defense capabilities. At the end of March 1453, emperor Constantine XI ordered a census of districts to record how many able-bodied men were in the city and whatever weapons each possessed for defense. George Sphrantzes, the faithful chancellor of the last emperor, recorded that "in spite of the great size of our city, our defenders amounted to 4,773 Greeks, as well as just 200 foreigners". In addition there were volunteers from outside, the "Genoese, Venetians and those who came secretly from Galata to help the defense", who numbered "hardly as many as three thousand", amounting to something under 8,000 men in total to defend a perimeter wall of twelve miles.[88]

Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Empire on 29 May 1453.[89] Mehmed II intended to complete his father's mission and conquer Constantinople for the Ottomans. In 1452 he reached peace treaties with Hungary and Venice. He also began the construction of the Boğazkesen (later called the Rumelihisarı), a fortress at the narrowest point of the Bosphorus Strait, in order to restrict passage between the Black and Mediterranean seas. Mehmed then tasked the Hungarian gunsmith Urban with both arming Rumelihisarı and building cannon powerful enough to bring down the walls of Constantinople. By March 1453 Urban's cannon had been transported from the Ottoman capital of Edirne to the outskirts of Constantinople. In April, having quickly seized Byzantine coastal settlements along the Black Sea and Sea of Marmara, Ottoman troops in Rumelia and Anatolia assembled outside the Byzantine capital. Their fleet moved from Gallipoli to nearby Diplokionion, and the sultan himself set out to meet his army.[90]The Ottomans were commanded by 21-year-old Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II. The conquest of Constantinople followed a seven-week siege which had begun on 6 April 1453. The Empire fell on 29 May 1453.

The number of people captured by the Ottomans after the fall of the city was around 33,000. The small number of people left in the city indicates that there could not have been many residents there. The primary concern of Mehmed II in the early years of his reign was the construction and settlement of the city. However, since an insufficient number of Muslims accepted his invitation, the settlement of 30 abandoned neighborhoods with the inhabitants of formerly conquered areas became necessary.[85]

The Christian Orthodox city of Constantinople was now under Ottoman control. As tradition followed for the region, Ottoman soldiers had three days to pillage the city. When Mehmed II on the second day entered Constantinople through the Gate of Charisius (today known as Edirnekapı or Adrianople Gate), it is said that first thing he did was ride his horse to Hagia Sophia, which was not in good shape even though it was avoided in the pillage by strict orders. Displeased by the pillaging, Mehmed II ordered it to end, for it will be the capital of his empire. He then ordered that an imam meet him in Hagia Sophia in order to chant the adhan thus transforming the Orthodox cathedral into a Muslim mosque,[91][92] solidifying Islamic rule in Constantinople.[93]

Mehmed's main concern with Constantinople had to do with consolidating control over the city and rebuilding its defenses. After 45,000 captives were marched from the city, building projects were commenced immediately after the conquest, which included the repair of the walls, construction of the citadel, and building a new palace.[94] Mehmed issued orders across his empire that Muslims, Christians, and Jews should resettle the city, with Christians and Jews required to pay jizya and Muslims pay Zakat; he demanded that five thousand households needed to be transferred to Constantinople by September.[94] From all over the Islamic empire, prisoners of war and deported people were sent to the city: these people were called "Sürgün" in Turkish (Greek: σουργούνιδες).[95] Two centuries later, Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi gave a list of groups introduced into the city with their respective origins. Even today, many quarters of Istanbul, such as Aksaray, Çarşamba, bear the names of the places of origin of their inhabitants.[95] However, many people escaped again from the city, and there were several outbreaks of plague, so that in 1459 Mehmed allowed the deported Greeks to come back to the city.[95]

Constantinople was the largest and richest urban center in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea during the late Eastern Roman Empire, mostly as a result of its strategic position commanding the trade routes between the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea. It would remain the capital of the eastern, Greek-speaking empire for over a thousand years and in some ways is the nexus of Byzantine art production. At its peak, roughly corresponding to the Middle Ages, it was one of the richest and largest cities in Europe. It exerted a powerful cultural pull and dominated much of the economic life in the Mediterranean. Visitors and merchants were especially struck by the beautiful monasteries and churches of the city, in particular the Hagia Sophia, or the Church of Holy Wisdom. According to Russian 14th-century traveler Stephen of Novgorod: "As for Hagia Sophia, the human mind can neither tell it nor make description of it."

It was especially important for preserving in its libraries manuscripts of Greek and Latin authors throughout a period when instability and disorder caused their mass-destruction in western Europe and north Africa: On the city's fall, thousands of these were brought by refugees to Italy, and played a key part in stimulating the Renaissance, and the transition to the modern world. The cumulative influence of the city on the west, over the many centuries of its existence, is incalculable. In terms of technology, art and culture, as well as sheer size, Constantinople was without parallel anywhere in Europe for a thousand years. Many languages were spoken in Constantinople. A 16th century Chinese geographical treatise specifically recorded that there were translators living in the city, indicating it was multilingual, multicultural, and cosmopolitan.[96]

.jpg/440px-Basilica_Cistern_after_restoration_2022_(11).jpg)

Constantinople was home to the first known Western Armenian journal published and edited by a woman (Elpis Kesaratsian). Entering circulation in 1862, Kit'arr or Guitar stayed in print for only seven months. Female writers who openly expressed their desires were viewed as immodest, but this changed slowly as journals began to publish more "women's sections". In the 1880s, Matteos Mamurian invited Srpouhi Dussap to submit essays for Arevelian Mamal. According to Zaruhi Galemkearian's autobiography, she was told to write about women's place in the family and home after she published two volumes of poetry in the 1890s. By 1900, several Armenian journals had started to include works by female contributors including the Constantinople-based Tsaghik.[97]

Even before Constantinople was founded, the markets of Byzantion were mentioned first by Xenophon and then by Theopompus who wrote that Byzantians "spent their time at the market and the harbour". In Justinian's age the Mese street running across the city from east to west was a daily market. Procopius claimed "more than 500 prostitutes" did business along the market street. Ibn Batutta who traveled to the city in 1325 wrote of the bazaars "Astanbul" in which the "majority of the artisans and salespeople in them are women".[98]

.jpg/440px-Hagia_Sophia_(15468276434).jpg)

The Byzantine Empire used Roman and Greek architectural models and styles to create its own unique type of architecture. The influence of Byzantine architecture and art can be seen in the copies taken from it throughout Europe. Particular examples include St Mark's Basilica in Venice,[99] the basilicas of Ravenna, and many churches throughout the Slavic East. Also, alone in Europe until the 13th-century Italian florin, the Empire continued to produce sound gold coinage, the solidus of Diocletian becoming the bezant prized throughout the Middle Ages. Its city walls were much imitated (for example, see Caernarfon Castle) and its urban infrastructure was moreover a marvel throughout the Middle Ages, keeping alive the art, skill and technical expertise of the Roman Empire. In the Ottoman period Islamic architecture and symbolism were used. Great bathhouses were built in Byzantine centers such as Constantinople and Antioch.[100]

Constantine's foundation gave prestige to the Bishop of Constantinople, who eventually came to be known as the Ecumenical Patriarch, and made it a prime center of Christianity alongside Rome. This contributed to cultural and theological differences between Eastern and Western Christianity eventually leading to the Great Schism that divided Western Catholicism from Eastern Orthodoxy from 1054 onwards. Constantinople is also of great religious importance to Islam, as the conquest of Constantinople is one of the signs of the End time in Islam.

There were many institutions in ancient Constantinople such as the Imperial University of Constantinople, sometimes known as the University of the Palace Hall of Magnaura (Greek: Πανδιδακτήριον τῆς Μαγναύρας), an Eastern Roman educational institution that could trace its corporate origins to 425 AD, when the emperor Theodosius II founded the Pandidacterium (Medieval Greek: Πανδιδακτήριον).[101]

The first film shown in Constantinople (and the Ottoman Empire) was, L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat, by the Lumière Brothers in 1896.

The first film made in Constantinople (and the Ottoman Empire) was, Ayastefanos'taki Rus Abidesinin Yıkılışı, by Fuat Uzkınay in 1914.

In the past the Bulgarian newspapers in the late Ottoman period were Makedoniya, Napredŭk, and Pravo.[102]

Between 1908 (after the Young Turk Revolution) and 1914 (start of World War I) the "Kurdistan Newspaper" was published in Constantinople by Mikdad Midhad Bedir Khan, before that it was published in exile in Cairo, Egypt.[103]

The city acted as a defence for the eastern provinces of the old Roman Empire against the barbarian invasions of the 5th century. The 18-meter-tall walls built by Theodosius II were, in essence, impregnable to the barbarians coming from south of the Danube river, who found easier targets to the west rather than the richer provinces to the east in Asia. From the 5th century, the city was also protected by the Anastasian Wall, a 60-kilometer chain of walls across the Thracian peninsula. Many scholars[who?] argue that these sophisticated fortifications allowed the east to develop relatively unmolested while Ancient Rome and the west collapsed.[104]

Constantinople's fame was such that it was described even in contemporary Chinese histories, the Old and New Book of Tang, which mentioned its massive walls and gates as well as a purported clepsydra mounted with a golden statue of a man.[105][106][107] The Chinese histories even related how the city had been besieged in the 7th century by Mu'awiya I and how he exacted tribute in a peace settlement.[106][108]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)