Германская империя (нем. Deutsches Reich ), [a] [15] [16] [17] [18] также называемая Германской империей , [19] Вторым рейхом [b] [20] или просто Германией , была периодом Германского рейха [21] [22] с момента объединения Германии в 1871 году до Ноябрьской революции 1918 года, когда Германский рейх изменил свою форму правления с монархии на республику . [23] [24]

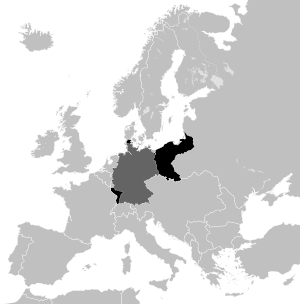

Империя была основана 18 января 1871 года в Версальском дворце , за пределами Парижа , Франция , где южногерманские государства, за исключением Австрии и Лихтенштейна , присоединились к Северогерманскому союзу , а новая конституция вступила в силу 16 апреля, изменив название федерального государства на Германскую империю и введя титул германского императора для Вильгельма I , короля Пруссии из дома Гогенцоллернов . [25] Берлин оставался его столицей, а Отто фон Бисмарк , министр-президент Пруссии , стал канцлером , главой правительства. Когда происходили эти события, возглавляемый Пруссией Северогерманский союз и его южногерманские союзники, такие как Баден , Бавария , Вюртемберг и Гессен , все еще были вовлечены во Франко-прусскую войну . Германская империя состояла из 25 государств , каждое со своим дворянством , четырех составляющих королевств , шести великих герцогств , пяти герцогств (шесть до 1876 года), семи княжеств , трех свободных ганзейских городов и одной имперской территории . Хотя Пруссия была одним из четырех королевств в королевстве, она содержала около двух третей населения и территории Империи, и прусское господство также было установлено конституционно, поскольку король Пруссии был также германским императором ( Deutscher Kaiser ).

После 1850 года государства Германии быстро стали индустриализированными, с особыми преимуществами в угле, железной (а позже и стали), химической промышленности и железных дорогах. В 1871 году население Германии составляло 41 миллион человек; к 1913 году оно увеличилось до 68 миллионов. В 1815 году, будучи в основном сельским собранием государств, теперь объединенная Германия стала преимущественно городской. [26] Успех немецкой индустриализации проявился двумя способами в начале 20-го века; немецкие фабрики часто были крупнее и современнее многих их британских и французских коллег, но доиндустриальный сектор был более отсталым. [27] Успех Германской империи в естественных науках, особенно в физике и химии, был таков, что треть всех Нобелевских премий досталась немецким изобретателям и исследователям. За 47 лет своего существования Германская империя стала промышленной, технологической и научной державой в Европе, и к 1913 году Германия была крупнейшей экономикой в континентальной Европе и третьей по величине в мире. [28] Германия также стала великой державой , построив самую длинную железнодорожную сеть в Европе, самую сильную армию в мире [29] и быстрорастущую промышленную базу. [30] Начав с очень малого размера в 1871 году, за десятилетие флот стал вторым после Королевского флота Великобритании .

С 1871 по 1890 год, пребывание Отто фон Бисмарка в качестве первого и по сей день самого долгого канцлера было отмечено относительным либерализмом в начале, но со временем стало более консервативным. Широкие реформы, антикатолический Kulturkampf и систематические репрессии поляков ознаменовали его период на посту. Несмотря на его ненависть к либерализму и социализму — он называл либералов и социалистов «врагами Рейха», — социальные программы, введенные Бисмарком, включали пенсии по старости, страхование от несчастных случаев, медицинское обслуживание и страхование по безработице, все аспекты современного европейского государства всеобщего благосостояния .

В конце канцлерства Бисмарка и несмотря на его раннее личное противодействие, Германия занялась колониализмом . Захватив большую часть оставшихся территорий, которые еще не были завоеваны европейцами в борьбе за Африку , она сумела построить третью по величине колониальную империю того времени после британской и французской . [31] Будучи колониальным государством, она иногда сталкивалась с интересами других европейских держав, особенно Британской империи. Во время своей колониальной экспансии Германская империя совершила геноцид гереро и намаква . [32]

После отставки Отто фон Бисмарка в 1890 году и отказа Вильгельма II вернуть его на пост империя приступила к Weltpolitik («мировой политике») — новому воинственному курсу, который в конечном итоге способствовал началу Первой мировой войны. Преемники Бисмарка были неспособны поддерживать сложные, изменчивые и пересекающиеся союзы своего предшественника, которые удерживали Германию от дипломатической изоляции. Этот период был отмечен усилением притеснения польского народа и различными факторами, влияющими на решения императора, которые часто воспринимались общественностью как противоречивые или непредсказуемые. В 1879 году Германская империя объединила Двойной союз с Австро-Венгрией , за которым в 1882 году последовал Тройственный союз с Италией . Она также сохранила прочные дипломатические связи с Османской империей . Когда наступил великий кризис 1914 года , Италия вышла из союза, а Османская империя формально вступила в союз с Германией .

В Первую мировую войну немецкие планы быстро захватить Париж осенью 1914 года провалились, и война на Западном фронте зашла в тупик. Морская блокада союзников привела к острой нехватке продовольствия и пищевых добавок. Однако имперская Германия добилась успеха на Восточном фронте ; она оккупировала большую часть территории к востоку от себя после Брест-Литовского мира . Немецкое заявление о неограниченной подводной войне в начале 1917 года способствовало вовлечению Соединенных Штатов в войну. В октябре 1918 года, после провала Весеннего наступления , немецкие армии отступали , союзники Австро-Венгрия и Османская империя рухнули, а Болгария капитулировала. Империя рухнула в результате Революции в ноябре 1918 года с отречением Вильгельма II, что оставило послевоенную федеративную республику управлять опустошенным населением. Версальский договор установил послевоенные репарационные расходы в размере 132 миллиардов золотых марок (около 269 миллиардов долларов США или 240 миллиардов евро в 2019 году или примерно 32 миллиарда долларов США в 1921 году) [33] , а также ограничил армию 100 000 человек и запретил воинскую повинность, бронетехнику, подводные лодки, самолеты и более шести линкоров. [34] Последующее экономическое опустошение, позднее усугубленное Великой депрессией , а также унижение и возмущение, испытанные немецким населением, считаются ведущими факторами подъема Адольфа Гитлера и нацизма . [35]

Германский союз был создан актом Венского конгресса 8 июня 1815 года в результате Наполеоновских войн , после того как он был упомянут в статье 6 Парижского договора 1814 года . [36]

Либеральные революции 1848 года были подавлены после того, как отношения между образованными, обеспеченными либералами среднего класса и городскими ремесленниками рухнули; прагматичная Realpolitik Отто фон Бисмарка , которая была обращена как к крестьянам, так и к аристократии, заняла ее место. [37] Бисмарк стремился распространить гегемонию Гогенцоллернов на все германские государства; сделать это означало объединить германские государства и исключить главного немецкого соперника Пруссии , Австрию , из последующей Германской империи. Он представлял себе консервативную Германию с доминированием Пруссии. Вторая Шлезвигская война против Дании в 1864 году, Австро-прусская война в 1866 году и Франко-прусская война в 1870–1871 годах вызвали рост пангерманского идеала и способствовали формированию германского государства.

Германский союз прекратил свое существование в результате австро-прусской войны 1866 года между составляющими конфедерацию субъектами Австрийской империи и ее союзниками с одной стороны и Пруссией и ее союзниками с другой. Война привела к частичной замене конфедерации в 1867 году Северогерманской конфедерацией , включавшей 22 государства к северу от реки Майн . Патриотический пыл, порожденный франко-прусской войной 1870 года, подавил оставшуюся оппозицию объединенной Германии (кроме Австрии) в четырех государствах к югу от Майна, и в ноябре 1870 года они присоединились к Северогерманскому союзу по договору. [38]

10 декабря 1870 года Рейхстаг Северогерманского союза переименовал Союз в «Германскую империю» и дал титул германского императора Вильгельму I , королю Пруссии , как Бундеспрезидиуму Союза. [39] Новая конституция ( Конституция Германского союза ) и титул императора вступили в силу 1 января 1871 года. Во время осады Парижа 18 января 1871 года Вильгельм был провозглашен императором в Зеркальном зале Версальского дворца . [ 40]

Вторая немецкая конституция , принятая рейхстагом 14 апреля 1871 года и провозглашенная императором 16 апреля, [40] в значительной степени основывалась на северогерманской конституции Бисмарка . Политическая система осталась прежней. В империи был парламент, называемый рейхстагом , который избирался всеобщим мужским голосованием . Однако первоначальные избирательные округа, нарисованные в 1871 году, никогда не перекраивались, чтобы отразить рост городских территорий. В результате ко времени большого расширения немецких городов в 1890-х и 1900-х годах сельские районы были значительно перепредставлены .

.jpg/440px-A_v_Werner_-_Kaiserproklamation_am_18_Januar_1871_(3._Fassung_1885).jpg)

Законодательство также требовало согласия Бундесрата , федерального совета депутатов 27 земель. Исполнительная власть принадлежала императору, или кайзеру , которому помогал канцлер, ответственный только перед ним. Императору конституция давала обширные полномочия. Он один назначал и увольнял канцлера (поэтому на практике император управлял империей через канцлера), был верховным главнокомандующим вооруженными силами и окончательным арбитром всех иностранных дел, а также мог распустить Рейхстаг, чтобы назначить новые выборы. Официально канцлер был единоличным кабинетом и отвечал за ведение всех государственных дел; на практике государственные секретари (высшие бюрократические должностные лица, отвечающие за такие области, как финансы, война, иностранные дела и т. д.) функционировали во многом так же, как министры в других монархиях. Рейхстаг имел право принимать, изменять или отклонять законопроекты и инициировать законодательство. Однако, как уже упоминалось выше, на практике реальная власть принадлежала императору, который осуществлял ее через своего канцлера.

Хотя номинально это была федеративная империя и союз равных, на практике империя находилась под контролем крупнейшего и самого могущественного государства — Пруссии. Она простиралась на северные две трети нового Рейха и вмещала три пятых населения страны. Императорская корона была наследственной в правящем доме Пруссии, доме Гогенцоллернов . За исключением 1872–1873 и 1892–1894 годов, канцлер всегда был одновременно премьер-министром Пруссии. Имея 17 из 58 голосов в Бундесрате , Берлину требовалось всего несколько голосов от более мелких государств, чтобы осуществлять эффективный контроль.

Другие штаты сохранили свои правительства, но имели лишь ограниченные аспекты суверенитета. Например, как почтовые марки, так и валюта выпускались для всей империи. Монеты до одной марки также чеканились от имени империи, в то время как более дорогие монеты выпускались штатами. Однако эти более крупные выпуски из золота и серебра были фактически памятными монетами и имели ограниченный тираж.

В то время как государства выпускали собственные награды , а некоторые имели собственные армии, военные силы более мелких государств были поставлены под прусский контроль. Военные силы более крупных государств, таких как королевства Бавария и Саксония, координировались по прусским принципам и в военное время контролировались федеральным правительством.

Эволюция Германской империи в некоторой степени соответствует параллельному развитию в Италии, которая стала единым национальным государством десятилетием ранее. Некоторые ключевые элементы авторитарной политической структуры Германской империи также были основой для консервативной модернизации в императорской Японии при императоре Мэйдзи и сохранения авторитарной политической структуры при царях в Российской империи .

Одним из факторов социальной анатомии этих правительств было сохранение весьма значительной доли политической власти земельной элиты , юнкеров , что было результатом отсутствия революционного прорыва со стороны крестьян в сочетании с городскими районами.

Хотя империя была авторитарной во многих отношениях, она имела некоторые демократические черты. Помимо всеобщего избирательного права для мужчин, она допускала развитие политических партий. Бисмарк намеревался создать конституционный фасад, который скрыл бы продолжение авторитарной политики. Однако в процессе он создал систему с серьезным недостатком. Существовало значительное несоответствие между прусской и немецкой избирательными системами. Пруссия использовала трехклассную систему голосования , которая взвешивала голоса на основе суммы уплаченных налогов, [41] почти гарантируя консервативное большинство. Король и (за двумя исключениями) премьер-министр Пруссии были также императором и канцлером империи — это означало, что те же самые правители должны были искать большинство в законодательных органах, избранных из совершенно разных избирательных округов. Всеобщее избирательное право было значительно разбавлено грубым перепредставлением сельских районов с 1890-х годов и далее. К рубежу веков баланс городского и сельского населения полностью изменился с 1871 года; более двух третей населения империи проживало в городах и поселках.

Внутренняя политика Бисмарка сыграла важную роль в формировании авторитарной политической культуры кайзеровской Германии . Менее озабоченное континентальной политикой власти после объединения в 1871 году, полупарламентское правительство Германии провело сравнительно плавную экономическую и политическую революцию сверху, которая подтолкнула их к тому, чтобы стать ведущей промышленной державой мира того времени.

«Революционный консерватизм» Бисмарка был консервативной стратегией государственного строительства, призванной сделать простых немцев — а не только юнкерскую элиту — более лояльными к трону и империи. По словам Кеса ван Керсбергена и Барбары Вис, его стратегия была:

предоставление социальных прав для усиления интеграции иерархического общества, для установления связи между работниками и государством с целью укрепления последнего, для поддержания традиционных отношений власти между социальными и статусными группами и для обеспечения противовеса модернистским силам либерализма и социализма. [42]

Бисмарк создал современное государство всеобщего благосостояния в Германии в 1880-х годах и ввел всеобщее избирательное право для мужчин в 1871 году. [43] Он стал великим героем для немецких консерваторов, которые воздвигли множество памятников в его память и пытались подражать его политике. [44]

Внешняя политика Бисмарка после 1871 года была консервативной и стремилась сохранить баланс сил в Европе. Британский историк Эрик Хобсбаум заключает, что он «оставался бесспорным чемпионом мира в игре в многосторонние дипломатические шахматы в течение почти двадцати лет после 1871 года, [посвятив] себя исключительно и успешно поддержанию мира между державами». [45] Это был отход от его авантюрной внешней политики в отношении Пруссии, где он выступал за силу и экспансию, подчеркивая это, говоря: «Великие вопросы века решаются не речами и большинством голосов — это была ошибка 1848–49 годов — а железом и кровью». [46]

Главной заботой Бисмарка было то, что Франция замышляет месть после своего поражения во Франко-прусской войне . Поскольку у французов не хватало сил победить Германию самостоятельно, они искали союза с Россией или, возможно, даже с недавно реформированной империей Австро-Венгрия, которая полностью охватила бы Германию. Бисмарк хотел предотвратить это любой ценой и сохранить дружеские отношения с австрийцами и русскими, подписав Двойной союз (1879) с Австро-Венгрией в 1879 году. Двойной союз был оборонительным союзом, который был заключен против России и, по ассоциации, Франции, в случае, если союз не сработает с государством. Однако союз с Россией был заключен вскоре после подписания Двойного союза с Австрией, Dreikaiserbund (Союза трех императоров), в 1881 году. В этот период отдельные лица в немецких военных кругах выступали за упреждающий удар по России, но Бисмарк знал, что такие идеи были безрассудными. Однажды он написал, что «самые блестящие победы не помогут против русской нации из-за ее климата, ее пустыни и ее бережливости, и из-за того, что ей нужно защищать только одну границу», и потому что это оставит Германию с еще одним ожесточенным, обидчивым соседом. Несмотря на это, в 1882 году был подписан еще один союз между Германией, Австро-Венгрией и Италией, который эксплуатировал страхи немецких и австро-венгерских военных перед ненадежностью самой России. Этот союз, названный Тройственным союзом (1882) , просуществовал до 1915 года, когда Италия объявила войну Австро-Венгрии. Несмотря на отсутствие веры Германии, и особенно Австрии, в российский союз, Договор о перестраховке был впервые подписан в 1887 году и возобновлен до 1890 года, когда система Бисмарка рухнула после отставки Бисмарка.

Между тем, канцлер по-прежнему с опаской относился к любым внешнеполитическим событиям, которые хотя бы отдаленно напоминали войну. В 1886 году он принял меры, чтобы остановить попытку продажи лошадей Франции, поскольку они могли быть использованы для кавалерии, а также приказал провести расследование крупных закупок Россией лекарств у немецкого химического завода. Бисмарк упрямо отказывался слушать Георга Герберта Мюнстера , посла во Франции, который докладывал, что французы не стремятся к реваншистской войне и отчаянно хотят мира любой ценой.

Бисмарк и большинство его современников были консервативно настроены и сосредоточили свое внимание во внешней политике на соседних с Германией государствах. В 1914 году 60% немецких иностранных инвестиций приходилось на Европу, в отличие от всего лишь 5% британских инвестиций. Большая часть денег шла в развивающиеся страны, такие как Россия, у которых не было капитала или технических знаний для самостоятельной индустриализации. Строительство железной дороги Берлин-Багдад , финансируемое немецкими банками, было призвано в конечном итоге соединить Германию с Османской империей и Персидским заливом , но оно также столкнулось с британскими и российскими геополитическими интересами. Конфликт из-за Багдадской железной дороги был разрешен в июне 1914 года.

Многие считают внешнюю политику Бисмарка последовательной системой и частично ответственной за сохранение стабильности в Европе. [47] Она также была отмечена необходимостью сбалансировать осмотрительную оборону и желание освободиться от ограничений своего положения как крупной европейской державы. [47] Преемники Бисмарка не продолжили его внешнеполитическое наследие. Например, кайзер Вильгельм II, который уволил канцлера в 1890 году, позволил договору с Россией прекратить свое действие в пользу союза Германии с Австрией, что в конечном итоге привело к созданию более прочной коалиции между Россией и Францией. [48]

Немцы мечтали о колониальном империализме с 1848 года. [49] Хотя Бисмарк был мало заинтересован в приобретении заморских владений, большинство немцев были полны энтузиазма, и к 1884 году он приобрел Германскую Новую Гвинею . [50] К 1890-м годам немецкая колониальная экспансия в Азии и на Тихом океане ( залив Цзяочжоу и Тяньцзинь в Китае, Марианские острова , Каролинские острова , Самоа) привела к трениям с Великобританией, Россией, Японией и США. Крупнейшие колониальные предприятия были в Африке, [51] где войны гереро на территории современной Намибии в 1906–1907 годах привели к геноциду гереро и намаква . [52]

К 1900 году Германия стала крупнейшей экономикой в континентальной Европе и третьей по величине в мире после Соединенных Штатов и Британской империи , которые также были ее главными экономическими конкурентами. На протяжении всего своего существования она переживала экономический рост и модернизацию, возглавляемую тяжелой промышленностью. В 1871 году ее преимущественно сельское население составляло 41 миллион человек, а к 1913 году оно увеличилось до преимущественно городского населения в 68 миллионов человек. [53]

В течение 30 лет Германия боролась с Британией за то, чтобы стать ведущей промышленной державой Европы. Представителем германской промышленности был сталелитейный гигант Krupp , чей первый завод был построен в Эссене . К 1902 году один только завод стал «большим городом со своими улицами, своей полицией, пожарной службой и правилами дорожного движения. Имеется 150 километров железных дорог, 60 различных заводских зданий, 8500 станков, семь электростанций, 140 километров подземного кабеля и 46 воздушных линий». [54]

При Бисмарке Германия была мировым новатором в построении государства всеобщего благосостояния . Немецкие рабочие пользовались медицинскими пособиями, пособиями по несчастным случаям и пособиями по беременности и родам, столовыми, раздевалками и национальной пенсионной схемой. [55]

Индустриализация в Германии динамично развивалась, и немецкие производители начали захватывать внутренние рынки за счет британского импорта, а также конкурировать с британской промышленностью за рубежом, особенно в США. Немецкая текстильная и металлургическая промышленность к 1870 году превзошла британскую по организации и технической эффективности и вытеснила британских производителей на внутреннем рынке. Германия стала доминирующей экономической силой на континенте и второй по величине экспортной страной после Великобритании. [56]

Технический прогресс во время немецкой индустриализации происходил четырьмя волнами: железнодорожная волна (1877–1886), волна красителей (1887–1896), химическая волна (1897–1902) и волна электротехники (1903–1918). [57] Поскольку Германия индустриализировалась позже, чем Британия, она смогла смоделировать свои заводы по образцу британских, тем самым более эффективно используя свой капитал и избегая устаревших методов в своем скачке к технологическому охвату. Германия инвестировала больше, чем Британия, в исследования, особенно в химию, двигатели внутреннего сгорания и электричество. Доминирование Германии в физике и химии было таким, что треть всех Нобелевских премий досталась немецким изобретателям и исследователям. Немецкая картельная система (известная как Konzerne ), будучи значительно сконцентрированной, смогла более эффективно использовать капитал. Германия не была обременена дорогостоящей всемирной империей, которая нуждалась в защите. После аннексии Эльзаса и Лотарингии Германией в 1871 году, она поглотила части того, что было промышленной базой Франции. [58]

Германия обогнала британское производство стали в 1893 году, а производство чугуна в 1903 году. Немецкое производство стали и чугуна продолжало стремительно расширяться: между 1911 и 1913 годами немецкое производство стали и чугуна достигло четверти от общего мирового производства. [59]

Немецкие заводы были крупнее и современнее своих британских и французских коллег. [27] К 1913 году производство электроэнергии в Германии превысило совокупное производство электроэнергии в Великобритании, Франции, Италии и Швеции. [60]

К 1900 году немецкая химическая промышленность доминировала на мировом рынке синтетических красителей . [61] Три основные фирмы BASF , [62] Bayer и Hoechst производили несколько сотен различных красителей, наряду с пятью более мелкими фирмами. Имперская Германия создала крупнейшую в мире химическую промышленность, производство немецкой химической промышленности было на 60% выше, чем в Соединенных Штатах. [60] В 1913 году эти восемь фирм производили почти 90% мировых поставок красителей и продавали около 80% своей продукции за границу. Три основные фирмы также интегрировались в производство необходимого сырья и начали расширяться в другие области химии, такие как фармацевтика , фотопленка , сельскохозяйственные химикаты и электрохимия . Принятие решений на высшем уровне находилось в руках профессиональных наемных менеджеров; это привело к тому, что Чандлер назвал немецкие компании по производству красителей «первыми в мире по-настоящему управленческими промышленными предприятиями». [63] Было много побочных продуктов исследований, таких как фармацевтическая промышленность, которая возникла из химических исследований. [64]

К началу Первой мировой войны (1914–1918) немецкая промышленность переключилась на военное производство. Наибольший спрос был на уголь и сталь для производства артиллерии и снарядов, а также на химикаты для синтеза материалов, подлежащих импортным ограничениям, а также для химического оружия и военных поставок.

Не имея поначалу технологической базы, немцы импортировали свою инженерию и оборудование из Британии, но быстро освоили навыки, необходимые для эксплуатации и расширения железных дорог. Во многих городах новые железнодорожные мастерские были центрами технологической осведомленности и обучения, так что к 1850 году Германия была самодостаточной в удовлетворении потребностей строительства железных дорог, а железные дороги были основным стимулом для роста новой сталелитейной промышленности. Объединение Германии в 1870 году стимулировало консолидацию, национализацию в государственные компании и дальнейший быстрый рост. В отличие от ситуации во Франции, целью была поддержка индустриализации, и поэтому тяжелые линии пересекали Рур и другие промышленные районы и обеспечивали хорошее сообщение с крупными портами Гамбурга и Бремена . К 1880 году в Германии было 9400 локомотивов, тянущих 43 000 пассажиров и 30 000 тонн грузов, и она опережала Францию. [65] Общая длина немецких железнодорожных путей увеличилась с 21 000 км (13 000 миль) в 1871 году до 63 000 км (39 000 миль) к 1913 году, создав самую большую железнодорожную сеть в мире после Соединенных Штатов. [66] За немецкой железнодорожной сетью следовали Австро-Венгрия (43 280 км; 26 890 миль), Франция (40 770 км; 25 330 миль), Великобритания (32 623 км; 20 271 миля), Италия (18 873 км; 11 727 миль) и Испания (15 088 км; 9 375 миль). [67]

Создание империи под руководством Пруссии было победой концепции Kleindeutschland (Малая Германия) над концепцией Großdeutschland . Это означало, что Австро-Венгрия, многоэтническая империя со значительным немецкоязычным населением, останется за пределами немецкого национального государства. Политика Бисмарка заключалась в том, чтобы добиваться решения дипломатическим путем. [ необходима цитата ] Эффективный союз между Германией и Австрией сыграл важную роль в решении Германии вступить в Первую мировую войну в 1914 году. [ необходима цитата ]

Бисмарк объявил, что больше не будет никаких территориальных дополнений к Германии в Европе, и его дипломатия после 1871 года была сосредоточена на стабилизации европейской системы и предотвращении любых войн. Он преуспел, и только после его ухода с поста в 1890 году дипломатическая напряженность снова начала расти. [68]

После достижения формального объединения в 1871 году Бисмарк уделял много внимания делу национального единства. Он выступал против гражданских прав и эмансипации католиков, особенно против влияния Ватикана при папе Пии IX , и радикализма рабочего класса, представленного формирующейся Социал-демократической партией .

В 1871 году в Пруссии проживало 16 000 000 протестантов, как реформаторов, так и лютеран, и 8 000 000 католиков. Большинство людей, как правило, были разделены на свои религиозные миры, жили в сельских районах или городских кварталах, которые в подавляющем большинстве исповедовали одну и ту же религию, и отправляли своих детей в отдельные государственные школы, где преподавалась их религия. Было мало взаимодействия или смешанных браков. В целом протестанты имели более высокий социальный статус, а католики, скорее всего, были крестьянами-фермерами или неквалифицированными или полуквалифицированными промышленными рабочими. В 1870 году католики сформировали свою собственную политическую партию, Партию центра , которая в целом поддерживала объединение и большую часть политики Бисмарка. Однако Бисмарк не доверял парламентской демократии в целом и оппозиционным партиям в частности, особенно когда Партия центра продемонстрировала признаки получения поддержки среди диссидентских элементов, таких как польские католики в Силезии . Мощной интеллектуальной силой того времени был антикатолицизм , возглавляемый либеральными интеллектуалами, которые составляли важную часть коалиции Бисмарка. Они видели в католической церкви мощную силу реакции и антисовременности, особенно после провозглашения папской непогрешимости в 1870 году и ужесточения контроля Ватикана над местными епископами. [69]

Культуркампф, начатый Бисмарком в 1871–1880 годах, затронул Пруссию; хотя в Бадене и Гессене были похожие движения, остальная часть Германии не была затронута. Согласно новой имперской конституции, земли отвечали за религиозные и образовательные дела; они финансировали протестантские и католические школы. В июле 1871 года Бисмарк упразднил католическую секцию прусского Министерства церковных и образовательных дел, лишив католиков голоса на самом высоком уровне. Система строгого государственного надзора за школами применялась только в католических районах; протестантские школы были оставлены в покое. [70]

Гораздо более серьезными были майские законы 1873 года. Один из них ставил назначение любого священника в зависимость от его посещения немецкого университета, в отличие от семинарий, которые обычно использовали католики. Более того, все кандидаты на служение должны были сдать экзамен по немецкой культуре перед государственным советом, который отсеивал непримиримых католиков. Другое положение давало правительству право вето на большинство церковных мероприятий. Второй закон отменил юрисдикцию Ватикана над католической церковью в Пруссии; ее полномочия были переданы государственному органу, контролируемому протестантами. [71]

Почти все немецкие епископы, духовенство и миряне отвергли законность новых законов и проявили непокорность перед лицом все более тяжких наказаний и тюремных заключений, налагаемых правительством Бисмарка. К 1876 году все прусские епископы были заключены в тюрьму или в изгнании, а треть католических приходов осталась без священника. Столкнувшись с систематическим неповиновением, правительство Бисмарка ужесточило наказания и свои нападки, и было оспорено в 1875 году, когда папская энциклика объявила все церковное законодательство Пруссии недействительным и пригрозила отлучить любого католика, который подчинится. Насилия не было, но католики мобилизовали свою поддержку, создали многочисленные общественные организации, собрали деньги на оплату штрафов и сплотились вокруг своей церкви и Центристской партии. «Старая католическая церковь», которая отвергла Первый Ватиканский собор, привлекла всего несколько тысяч членов. Бисмарк, набожный пиетист-протестант, понял, что его Kulturkampf имел обратный эффект, когда светские и социалистические элементы использовали возможность для нападок на все религии. В долгосрочной перспективе самым значительным результатом стала мобилизация католических избирателей и их настойчивость в защите своей религиозной идентичности. На выборах 1874 года Центристская партия удвоила свои голоса избирателей и стала второй по величине партией в национальном парламенте — и оставалась мощной силой в течение следующих 60 лет, так что после Бисмарка стало трудно сформировать правительство без их поддержки. [72] [73]

Бисмарк основывался на традиции программ социального обеспечения в Пруссии и Саксонии, которая началась еще в 1840-х годах. В 1880-х годах он ввел пенсии по старости, страхование от несчастных случаев, медицинское обслуживание и страхование по безработице, которые легли в основу современного европейского государства всеобщего благосостояния . Он пришел к выводу, что такого рода политика была очень привлекательной, поскольку она связывала рабочих с государством, а также очень хорошо соответствовала его авторитарной натуре. Системы социального обеспечения, установленные Бисмарком (здравоохранение в 1883 году, страхование от несчастных случаев в 1884 году, страхование по инвалидности и старости в 1889 году), в то время были крупнейшими в мире и, в некоторой степени, все еще существуют в Германии сегодня.

Патерналистские программы Бисмарка получили поддержку немецкой промышленности, поскольку их целью было завоевать поддержку рабочего класса для Империи и сократить отток иммигрантов в Америку, где заработная плата была выше, но благосостояния не существовало. [55] [74] Бисмарк также получил поддержку как промышленности, так и квалифицированных рабочих своей политикой высоких тарифов, которая защищала прибыли и заработную плату от американской конкуренции, хотя она и оттолкнула либеральных интеллектуалов, которые хотели свободной торговли. [75]

Как и во всей Европе того времени, антисемитизм был распространен в Германии в этот период. До того, как указы Наполеона положили конец гетто в Рейнском союзе , он был религиозно мотивирован, но к 19 веку он стал фактором немецкого национализма . В общественном сознании евреи стали символом капитализма и богатства. С другой стороны, конституция и правовая система защищали права евреев как немецких граждан. Антисемитские партии были сформированы, но вскоре распались. [76] Но после Версальского договора и прихода Адольфа Гитлера к власти в Германии антисемитизм в Германии усилился. [77]

Одним из последствий политики объединения стала постепенно усиливающаяся тенденция к устранению использования негерманских языков в общественной жизни, школах и академических учреждениях с целью давления на ненемецкое население с целью отказа от своей национальной идентичности в том, что называлось « германизацией ». Эта политика часто имела обратный эффект, стимулируя сопротивление, обычно в форме домашнего обучения и более тесного единства в группах меньшинств, особенно поляков . [78]

Политика германизации была направлена в первую очередь против значительного польского меньшинства империи, полученного Пруссией в результате разделов Польши . Поляки рассматривались как этническое меньшинство даже там, где они составляли большинство, как в провинции Познань , где был принят ряд антипольских мер. [79] Многочисленные антипольские законы не имели большого эффекта, особенно в провинции Познань, где немецкоязычное население сократилось с 42,8% в 1871 году до 38,1% в 1905 году, несмотря на все усилия. [80]

Усилия Бисмарка также инициировали нивелирование огромных различий между немецкими государствами, которые были независимы в своей эволюции на протяжении столетий, особенно в области законодательства. Совершенно разные правовые истории и судебные системы создавали огромные осложнения, особенно для национальной торговли. Хотя общий торговый кодекс был введен Конфедерацией уже в 1861 году (который был адаптирован для Империи и, с большими изменениями, действует и по сей день), в остальном в законах было мало сходства.

В 1871 году был введен общий уголовный кодекс ; в 1877 году общие судебные процедуры были установлены в судебной системе законом о конституции судов , гражданским процессуальным кодексом ( Zivilprozessordnung ) и уголовным процессуальным кодексом ( Strafprozessordnung [de] ). В 1873 году в конституцию были внесены поправки, позволяющие Империи заменить различные и сильно отличающиеся гражданские кодексы государств (если они вообще существовали; например, части Германии, ранее оккупированные наполеоновской Францией, приняли французский гражданский кодекс, в то время как в Пруссии все еще действовал Allgemeines Preußisches Landrecht 1794 года). В 1881 году была создана первая комиссия для разработки общего гражданского кодекса для всей Империи, что потребовало огромных усилий, в результате которых был создан Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB), возможно, один из самых впечатляющих юридических трудов в мире; В конечном итоге он вступил в силу 1 января 1900 года. Все эти кодификации , хотя и со многими поправками, действуют и сегодня.

9 марта 1888 года Вильгельм I умер незадолго до своего 91-го дня рождения, оставив своего сына Фридриха новым императором. Фридрих был либералом и поклонником британской конституции, [81] в то время как его связи с Британией еще больше укрепились с его женитьбой на принцессе Виктории , старшей дочери королевы Виктории . С его восхождением на престол многие надеялись, что правление Фридриха приведет к либерализации Рейха и увеличению влияния парламента на политический процесс. Увольнение Роберта фон Путткамера , крайне консервативного прусского министра внутренних дел , 8 июня было знаком ожидаемого направления и ударом по администрации Бисмарка.

Однако к моменту восшествия на престол у Фридриха развился неизлечимый рак гортани , диагностированный в 1887 году. Он умер на 99-й день своего правления, 15 июня 1888 года. Императором стал его сын Вильгельм .

Вильгельм II хотел восстановить свои прерогативы правления в то время, когда другие монархи в Европе превращались в конституционных деятелей. Это решение привело амбициозного кайзера к конфликту с Бисмарком. Старый канцлер надеялся руководить Вильгельмом так же, как он руководил его дедом, но император хотел быть хозяином в своем собственном доме и имел множество подхалимов, говоривших ему, что Фридрих Великий не был бы великим с Бисмарком рядом с ним. [82] Ключевым различием между Вильгельмом II и Бисмарком был их подход к урегулированию политических кризисов, особенно в 1889 году, когда немецкие шахтеры устроили забастовку в Верхней Силезии . Бисмарк потребовал, чтобы немецкая армия была направлена для подавления забастовки, но Вильгельм II отверг эту авторитарную меру, ответив: «Я не хочу пятнать свое правление кровью моих подданных». [83] Вместо того, чтобы мириться с репрессиями, Вильгельм заставил правительство вести переговоры с делегацией шахтеров, что привело к прекращению забастовки без насилия. [82] Непростые отношения закончились в марте 1890 года после того, как Вильгельм II и Бисмарк поссорились, а канцлер ушел в отставку несколько дней спустя. [82]

С уходом Бисмарка Вильгельм II стал доминирующим правителем Германии. В отличие от своего деда Вильгельма I, который в значительной степени был согласен оставить государственные дела канцлеру, Вильгельм II хотел быть полностью информированным и активно участвовать в управлении Германией, а не быть декоративной фигурой, хотя большинство немцев находили его претензии на божественное право на власть забавными. [84] Вильгельм позволил политику Вальтеру Ратенау обучать его европейской экономике, а также промышленным и финансовым реалиям в Европе. [84]

Как отмечает Халл (2004), внешняя политика Бисмарка «была слишком спокойной для безрассудного кайзера». [85] Вильгельм стал известен на международном уровне своей агрессивной позицией во внешней политике и своими стратегическими ошибками (такими как Танжерский кризис ), которые привели Германскую империю к растущей политической изоляции и в конечном итоге способствовали началу Первой мировой войны .

При Вильгельме II в Германии больше не было долго правящих сильных канцлеров, таких как Бисмарк. Новые канцлеры испытывали трудности в исполнении своих ролей, особенно дополнительной роли премьер-министра Пруссии, отведенной им в Конституции Германии. Реформы канцлера Лео фон Каприви , либерализовавшие торговлю и тем самым сократившие безработицу, были поддержаны кайзером и большинством немцев, за исключением прусских землевладельцев, которые боялись потери земли и власти и начали несколько кампаний против реформ. [86]

В то время как прусские аристократы оспаривали требования единого немецкого государства, в 1890-х годах было создано несколько организаций, чтобы бросить вызов авторитарному консервативному прусскому милитаризму, который навязывался стране. Педагоги, выступавшие против немецких государственных школ, которые делали упор на военное образование, создали свои собственные независимые либеральные школы, которые поощряли индивидуальность и свободу. [87] Однако почти все школы в имперской Германии имели очень высокий стандарт и шли в ногу с современными достижениями в области знаний. [88]

Художники начали экспериментальное искусство в противовес поддержке традиционного искусства кайзером Вильгельмом, на что Вильгельм ответил: «Искусство, которое нарушает установленные мной законы и ограничения, больше не может называться искусством». [89] Во многом благодаря влиянию Вильгельма большинство печатных материалов в Германии использовали готический шрифт вместо римского, используемого в остальной части Западной Европы. В то же время появилось новое поколение творцов культуры. [90]

Начиная с 1890-х годов наиболее эффективной оппозицией монархии была недавно сформированная Социал-демократическая партия Германии (СДПГ), радикалы которой отстаивали марксизм . Угроза СДПГ немецкой монархии и промышленникам заставила государство как принять жесткие меры против сторонников партии, так и реализовать собственную программу социальных реформ для успокоения недовольства. Крупные промышленные предприятия Германии предоставляли значительные программы социального обеспечения и хорошую заботу своим сотрудникам, пока они не были идентифицированы как социалисты или члены профсоюза. Крупные промышленные предприятия предоставляли пенсии, пособия по болезни и даже жилье своим сотрудникам. [87]

Извлекши урок из провала Культуркампфа Бисмарка , Вильгельм II поддерживал хорошие отношения с Римско-католической церковью и сосредоточился на противодействии социализму. [91] Эта политика потерпела неудачу, когда социал-демократы получили треть голосов на выборах в Рейхстаг 1912 года и стали крупнейшей политической партией в Германии. Правительство оставалось в руках череды консервативных коалиций, поддерживаемых правыми либералами или католическими священнослужителями и сильно зависевших от благосклонности кайзера. Растущий милитаризм при Вильгельме II заставил многих немцев эмигрировать в США и британские колонии, чтобы избежать обязательной военной службы.

Во время Первой мировой войны кайзер все больше передавал свои полномочия лидерам германского верховного командования, в частности будущему немецкому президенту , фельдмаршалу Паулю фон Гинденбургу и генерал-квартирмейстеру Эриху Людендорфу . Гинденбург принял на себя роль главнокомандующего от кайзера, в то время как Людендорф стал фактически генеральным начальником штаба. К 1916 году Германия фактически стала военной диктатурой, которой управляли Гинденбург и Людендорф, а кайзер был сведен к простой номинальной фигуре. [92]

Вильгельм II хотел, чтобы Германия имела свое « место под солнцем », как Британия, с которой он постоянно хотел соперничать или которой он хотел подражать. [93] Поскольку немецкие торговцы и купцы уже действовали по всему миру, он поощрял колониальные усилия в Африке и на Тихом океане (« новый империализм »), заставляя Германскую империю соперничать с другими европейскими державами за оставшиеся «невостребованными» территории. С поощрением или, по крайней мере, с согласия Британии, которая на этом этапе видела в Германии противовес своему старому сопернику Франции, Германия приобрела Германскую Юго-Западную Африку (современная Намибия ), Германскую Камерун (современный Камерун ), Тоголенд (современный Того ) и Германскую Восточную Африку (современные Руанда , Бурунди и материковая часть нынешней Танзании ). Острова были получены в Тихом океане путем покупки и договоров, а также 99-летней аренды территории Цзяочжоу на северо-востоке Китая. Но из этих немецких колоний только Тоголенд и Германское Самоа (после 1908 года) стали самодостаточными и прибыльными; Всем остальным требовались субсидии из берлинской казны на строительство инфраструктуры, школьных систем, больниц и других учреждений.

Бисмарк изначально с презрением отнесся к агитации за колонии; он выступал за европоцентристскую внешнюю политику, как показывают договорные соглашения, заключенные во время его пребывания в должности. Будучи опоздавшим в колонизации, Германия неоднократно вступала в конфликт с устоявшимися колониальными державами, а также с Соединенными Штатами, которые выступали против попыток Германии колониальной экспансии как в Карибском бассейне, так и в Тихом океане. Восстания коренных народов на немецких территориях получили широкое освещение в других странах, особенно в Великобритании; устоявшиеся державы уже справлялись с такими восстаниями десятилетиями ранее, часто жестоко, и к тому времени обеспечили себе прочный контроль над своими колониями. Боксерское восстание в Китае, которое в конечном итоге спонсировало китайское правительство, началось в провинции Шаньдун, отчасти потому, что Германия, как колонизатор в Цзяочжоу , была неопытной силой и действовала там всего два года. Семь западных стран, включая Соединенные Штаты и Японию, организовали совместные силы по оказанию помощи, чтобы спасти западных людей, оказавшихся в мятеже. Во время церемоний отъезда немецкого контингента Вильгельм II призвал их вести себя как гуннские захватчики континентальной Европы — неудачное замечание, которое позже будет воскрешено британскими пропагандистами, чтобы изобразить немцев как варваров во время Первой и Второй мировых войн [ по чьему мнению? ] . В двух случаях франко-германский конфликт из-за судьбы Марокко казался неизбежным.

После захвата Юго-Западной Африки немецкие поселенцы были поощрены возделывать земли, принадлежавшие гереро и нама . Земли племен гереро и нама использовались для различных целей эксплуатации (во многом так же, как это делали британцы в Родезии ), включая земледелие, скотоводство и добычу полезных ископаемых и алмазов . В 1904 году гереро и нама восстали против колонистов в Юго-Западной Африке, убив фермерские семьи, их рабочих и слуг. В ответ на нападения были отправлены войска для подавления восстания, которое затем привело к геноциду гереро и намаква . В общей сложности погибло около 65 000 гереро (80% от общей численности гереро) и 10 000 нама (50% от общей численности нама). Командующий карательной экспедицией генерал Лотар фон Трота в конечном итоге был освобожден и получил выговор за узурпацию приказов и жестокости, которые он творил. Эти события иногда называли «первым геноцидом XX века» и официально осудили в 1985 году Организацией Объединенных Наций. В 2004 году последовали официальные извинения министра правительства Федеративной Республики Германия.

Бисмарк и Вильгельм II после него стремились к более тесным экономическим связям с Османской империей . При Вильгельме II, при финансовой поддержке Deutsche Bank , в 1900 году было начато строительство Багдадской железной дороги , хотя к 1914 году она все еще была на 500 км (310 миль) дальше своего назначения в Багдаде. [94] В интервью с Вильгельмом в 1899 году Сесил Родс пытался «убедить кайзера, что будущее Германской империи за рубежом лежит на Ближнем Востоке», а не в Африке; с великой ближневосточной империей Германия могла позволить Великобритании беспрепятственно завершить строительство железной дороги от Мыса Доброй Надежды до Каира, которую поддерживал Родс. [95] Первоначально Великобритания поддерживала Багдадскую железную дорогу ; но к 1911 году британские государственные деятели стали опасаться, что она может быть продлена до Басры в Персидском заливе , что поставит под угрозу военно-морское превосходство Великобритании в Индийском океане. Соответственно, они потребовали остановить строительство, на что Германия и Османская империя согласились.

В Южной Америке Германия в первую очередь интересовалась Аргентиной, Бразилией, Чили и Уругваем и рассматривала страны северной части Южной Америки — Эквадор , Колумбию и Венесуэлу — как буфер для защиты своих интересов от растущего влияния Соединенных Штатов. [96] Политики в Германии анализировали возможность создания баз на острове Маргарита и проявляли интерес к Галапагосским островам, но вскоре отказались от любых подобных планов, учитывая, что отдаленные базы на севере Южной Америки были бы очень уязвимы. [97] [96] Германия пыталась продвинуть Чили, страну, находившуюся под сильным влиянием Германии , [98] в региональный противовес Соединенным Штатам. [96] Германии и Великобритании удалось через Чили заставить Эквадор отказать Соединенным Штатам в создании военно-морской базы на Галапагосских островах . [96]

Утверждения о том, что немецкие общины в Южной Америке действовали как продолжение Германской империи, были повсеместны к 1900 году, но никогда не было доказано, что эти общины действовали таким образом в какой-либо значительной степени. [99] Немецкое политическое, культурное и научное влияние было особенно интенсивным в Чили в десятилетия перед Первой мировой войной , и престиж Германии и немецких вещей в Чили оставался высоким после войны, но не восстановился до довоенного уровня. [98] [99]

Берлин с большим подозрением относился к предполагаемому заговору своих врагов: из года в год в начале 20-го века он был систематически окружен врагами. [100] Растет страх, что предполагаемая вражеская коалиция России, Франции и Великобритании становится сильнее в военном отношении с каждым годом, особенно Россия. Чем дольше Берлин ждал, тем меньше вероятность, что он победит в войне. [101] По словам американского историка Гордона А. Крейга , именно после неудачи в Марокко в 1905 году страх окружения стал мощным фактором в немецкой политике. [102] Мало кто из сторонних наблюдателей соглашался с представлением о Германии как о жертве преднамеренного окружения. [103] [104] Английский историк Г. М. Тревельян выразил британскую точку зрения:

Окружение, каким оно было, было делом рук самой Германии. Она сама себя окружила, оттолкнув Францию из-за Эльзаса и Лотарингии, Россию — поддержав антиславянскую политику Австро-Венгрии на Балканах, Англию — построив свой флот-соперник. Она создала с Австро-Венгрией военный блок в самом сердце Европы, настолько мощный и в то же время беспокойный, что у ее соседей по обе стороны не было иного выбора, кроме как стать ее вассалами или вместе встать на защиту... Они использовали свое центральное положение, чтобы вселять страх во все стороны, чтобы достичь своих дипломатических целей. А затем они жаловались, что со всех сторон они были окружены. [105]

Вильгельм II, под давлением своих новых советников после ухода Бисмарка, совершил фатальную ошибку, когда решил позволить « Договору перестраховки », который Бисмарк заключил с царской Россией, прекратить свое действие. Это позволило России заключить новый союз с Францией. У Германии не осталось ни одного прочного союзника, кроме Австро-Венгрии , и ее поддержка действий по аннексии Боснии и Герцеговины в 1908 году еще больше испортила отношения с Россией. Берлин упустил возможность заключить союз с Великобританией в 1890-х годах, когда он был вовлечен в колониальное соперничество с Францией, и он еще больше оттолкнул британских государственных деятелей, открыто поддержав буров в Южноафриканской войне и построив флот, чтобы конкурировать с британским. К 1911 году Вильгельм полностью разрушил осторожный баланс сил, установленный Бисмарком, и Великобритания обратилась к Франции в Антанте Сердечном . Единственным другим союзником Германии, помимо Австрии, было Королевство Италия , но оно оставалось союзником только формально . Когда началась война, Италия увидела больше выгоды в союзе с Британией, Францией и Россией, которые в секретном Лондонском договоре 1915 года обещали ей приграничные районы Австрии, а также колониальные концессии. Германия действительно приобрела второго союзника в 1914 году, когда Османская империя вступила в войну на ее стороне, но в долгосрочной перспективе поддержка османских военных усилий только истощила немецкие ресурсы с главных фронтов. [106]

После убийства австро-венгерского эрцгерцога Франца Фердинанда Гаврилой Принципом кайзер предложил императору Францу Иосифу полную поддержку австро-венгерским планам вторжения в Королевство Сербии , которое Австро-Венгрия обвинила в убийстве. Эту безоговорочную поддержку Австро-Венгрии историки, включая немца Фрица Фишера , назвали «бланшированным чеком» . Последующее толкование — например, на Версальской мирной конференции — состояло в том, что этот «бланшированный чек» лицензировал австро-венгерскую агрессию независимо от дипломатических последствий, и, таким образом, Германия несла ответственность за начало войны или, по крайней мере, за провоцирование более масштабного конфликта.

Германия начала войну, нацелившись на своего главного соперника, Францию. Германия видела во Французской Республике свою главную опасность на европейском континенте, поскольку она могла мобилизоваться гораздо быстрее, чем Россия, и граничила с промышленным ядром Германии в Рейнской области . В отличие от Великобритании и России, французы вступили в войну в основном для мести Германии, в частности за потерю Францией Эльзаса и Лотарингии в пользу Германии в 1871 году. Германское высшее командование знало, что Франция соберет свои силы, чтобы войти в Эльзас и Лотарингию. Помимо очень неофициальной Septemberprogramm , немцы никогда не заявляли четкого списка целей, которых они хотели бы достичь в войне. [107]

Германия не хотела рисковать длительными сражениями вдоль франко-германской границы и вместо этого приняла план Шлиффена , военную стратегию, разработанную для того, чтобы парализовать Францию путем вторжения в Бельгию и Люксембург , охватив и раздавив как Париж, так и французские войска вдоль франко-германской границы в быстрой победе. После победы над Францией Германия должна была напасть на Россию. План требовал нарушения официального нейтралитета Бельгии и Люксембурга, который Британия гарантировала договором. Однако немцы рассчитывали, что Британия вступит в войну независимо от того, будут ли у них формальные основания для этого. [108] Сначала атака была успешной: немецкая армия пронеслась из Бельгии и Люксембурга и двинулась на Париж, у близлежащей реки Марна . Однако эволюция оружия за последнее столетие в значительной степени благоприятствовала обороне, а не наступлению, особенно благодаря пулемету, так что для преодоления оборонительной позиции требовалось пропорционально больше наступательной силы. Это привело к тому, что немецкие линии наступления сократились, чтобы сохранить график наступления, в то время как французские линии соответственно расширились. Кроме того, некоторые немецкие подразделения, которые изначально предназначались для немецких крайне правых, были переведены на Восточный фронт в ответ на то, что Россия мобилизовалась гораздо быстрее, чем предполагалось. Совокупный эффект привел к тому, что немецкий правый фланг устремился вниз перед Парижем, а не позади него, открыв немецкий правый фланг для расширяющихся французских линий и атаки стратегических французских резервов, размещенных в Париже. Атакуя открытый немецкий правый фланг, французская армия и британская армия оказали сильное сопротивление обороне Парижа в Первой битве на Марне , в результате чего немецкая армия отступила на оборонительные позиции вдоль реки Эна . Последующая гонка к морю привела к длительному тупику между немецкой армией и союзниками в окопавшихся позициях траншейной войны от Эльзаса до Фландрии .

Немецкие попытки прорваться провалились в двух сражениях при Ипре ( 1-е и 2-е ) с огромными потерями. Серия наступлений союзников в 1915 году против немецких позиций в Артуа и Шампани привела к огромным потерям союзников и незначительным территориальным изменениям. Немецкий начальник штаба Эрих фон Фалькенхайн решил использовать оборонительные преимущества, которые проявились в наступлениях союзников 1915 года, пытаясь спровоцировать Францию на атаку сильных оборонительных позиций вблизи древнего города Верден . Верден был одним из последних городов, который устоял против немецкой армии в 1870 году, и Фалькенхайн предсказал, что в качестве вопроса национальной гордости французы сделают все, чтобы гарантировать, что он не будет взят. Он ожидал, что сможет занять сильные оборонительные позиции на холмах, возвышающихся над Верденом на восточном берегу реки Маас, чтобы угрожать городу, и французы начнут отчаянные атаки на эти позиции. Он предсказал, что французские потери будут больше, чем у немцев, и что продолжение французских войск в Вердене «истощит французскую армию». В феврале 1916 года началась битва при Вердене , в ходе которой французские позиции подвергались постоянным обстрелам и атакам с применением отравляющих газов и несли большие потери под натиском подавляюще больших немецких сил. Однако предсказание Фалькенхайна о большем соотношении убитых французов оказалось неверным, поскольку обе стороны понесли тяжелые потери. Фалькенхайна сменил Эрих Людендорф , и, не видя успеха, немецкая армия отступила из Вердена в декабре 1916 года, и битва закончилась.

В то время как Западный фронт был тупиком для немецкой армии, Восточный фронт в конечном итоге оказался большим успехом. Несмотря на первоначальные неудачи из-за неожиданно быстрой мобилизации русской армии, которая привела к российскому вторжению в Восточную Пруссию и австрийскую Галицию , плохо организованная и снабженная русская армия дрогнула , а немецкая и австро-венгерская армии впоследствии неуклонно продвигались на восток. Немцы извлекли выгоду из политической нестабильности в России и желания ее населения закончить войну. В 1917 году немецкое правительство разрешило российскому коммунистическому большевистскому лидеру Владимиру Ленину проехать через Германию из Швейцарии в Россию. Германия считала, что если Ленин сможет создать дальнейшие политические беспорядки, Россия больше не сможет продолжать свою войну с Германией, что позволит немецкой армии сосредоточиться на Западном фронте.

В марте 1917 года царь был свергнут с российского престола, а в ноябре к власти пришло большевистское правительство под руководством Ленина. Столкнувшись с политической оппозицией, он решил прекратить кампанию России против Германии, Австро-Венгрии, Османской империи и Болгарии , чтобы перенаправить большевистскую энергию на устранение внутреннего инакомыслия. В марте 1918 года по Брест-Литовскому мирному договору большевистское правительство предоставило Германии и Османской империи огромные территориальные и экономические уступки в обмен на прекращение войны на Восточном фронте. Вся нынешняя Эстония , Латвия и Литва были переданы немецкой оккупационной власти Ober Ost , вместе с Белоруссией и Украиной . Таким образом, Германия наконец достигла своего долгожданного господства в «Mitteleuropa» (Центральной Европе) и теперь могла полностью сосредоточиться на разгроме союзников на Западном фронте. Однако на практике силы, которые были необходимы для гарнизона и обеспечения безопасности новых территорий, были истощением немецких военных усилий.

Германия быстро потеряла почти все свои колонии. Однако в Германской Восточной Африке партизанскую кампанию вел тамошний колониальный армейский лидер генерал Пауль Эмиль фон Леттов-Форбек . Используя немцев и местных аскари , Леттов-Форбек провел несколько партизанских рейдов против британских войск в Кении и Родезии . Он также вторгся в португальский Мозамбик , чтобы получить припасы для своих войск и забрать больше рекрутов аскари. Его силы все еще были активны в конце войны. [109]

Поражение России в 1917 году позволило Германии перебросить сотни тысяч солдат с Восточного на Западный фронт, что дало ей численное преимущество над союзниками . Переобучая солдат новой тактике проникновения , немцы рассчитывали разморозить поле боя и одержать решительную победу до того, как армия Соединенных Штатов, которая теперь вступила в войну на стороне союзников, прибудет с силами. [110] В том, что было известно как «кайзершлахт», Германия сосредоточила свои войска и нанесла несколько ударов, которые отбросили союзников. Однако все повторные немецкие наступления весной 1918 года потерпели неудачу, поскольку союзники отступили и перегруппировались, а у немцев не было резервов, необходимых для закрепления своих достижений. Тем временем солдаты стали радикальными из-за русской революции и были менее готовы продолжать сражаться. Военные действия вызвали гражданские беспорядки в Германии, в то время как войска, которые постоянно находились на поле боя без какой-либо помощи, истощились и потеряли всякую надежду на победу. Летом 1918 года британская армия достигла пика своей мощи: на западном фронте находилось около 4,5 миллионов человек, а для Стодневного наступления было задействовано 4000 танков. Американцы прибывали со скоростью 10 000 человек в день. Союзники Германии находились на грани краха, а людские ресурсы Германской империи были истощены. Это был лишь вопрос времени, когда многочисленные наступления союзников уничтожат немецкую армию. [111]

Концепция « тотальной войны » означала, что поставки должны были быть перенаправлены в сторону вооруженных сил, и, поскольку немецкая торговля была остановлена морской блокадой союзников , немецкие гражданские лица были вынуждены жить во все более скудных условиях. Сначала цены на продукты питания контролировались, затем было введено нормирование. Во время войны около 750 000 немецких гражданских лиц умерли от недоедания. [112]

К концу войны условия на внутреннем фронте стремительно ухудшались, и во всех городских районах отмечалась серьезная нехватка продовольствия. Причинами этого стали перевод многих фермеров и работников пищевой промышленности в армию в сочетании с перегруженной железнодорожной системой, нехваткой угля и британской блокадой. Зима 1916–1917 годов была известна как «зима репы», потому что людям приходилось выживать на овощах, которые обычно использовались для скота, в качестве замены картофелю и мясу, которых становилось все меньше. Были открыты тысячи бесплатных столовых, чтобы накормить голодных, которые ворчали, что фермеры оставляют еду себе. Даже армии пришлось урезать солдатские пайки. [113] Моральный дух как гражданских, так и солдат продолжал падать.

Население Германии уже страдало от вспышек болезней из-за недоедания из-за блокады союзников, препятствовавшей импорту продовольствия. Испанский грипп прибыл в Германию с возвращающимися войсками. Около 287 000 человек умерли от испанского гриппа в Германии между 1918 и 1920 годами, 50 000 из которых умерли только в Берлине.

Многие немцы хотели окончания войны, и все большее число людей стали ассоциироваться с политическими левыми, такими как Социал-демократическая партия (СДПГ) и более радикальная Независимая социал-демократическая партия (НСДПГ), которые требовали окончания войны. Вступление США в войну в апреле 1917 года еще больше изменило долгосрочный баланс сил в пользу союзников.

В конце октября 1918 года в Киле , на севере Германии, началась Немецкая революция 1918–1919 годов . Подразделения германского флота отказались отплыть для последней крупномасштабной операции в войне, которую они считали проигранной, инициировав восстание. 3 ноября восстание распространилось на другие города и земли страны, во многих из которых были созданы рабочие и солдатские советы . Тем временем Гинденбург и высшие генералы утратили доверие к кайзеру и его правительству.

Болгария подписала Салоникское перемирие 29 сентября 1918 года. Османская империя подписала Мудросское перемирие 30 октября 1918 года. Между 24 октября и 3 ноября 1918 года Италия победила Австро-Венгрию в битве при Витторио-Венето , что заставило Австро-Венгрию подписать перемирие в Вилла-Джусти 3 ноября 1918 года. Итак, в ноябре 1918 года, с внутренней революцией, союзниками, продвигающимися к Германии на Западном фронте , Австро-Венгрия разваливалась из-за многочисленных этнических противоречий, ее другие союзники вышли из войны и давления со стороны немецкого высшего командования, кайзер и все немецкие правящие короли, герцоги и князья отреклись от престола, и немецкое дворянство было упразднено. 9 ноября социал-демократ Филипп Шейдеман провозгласил республику . Новое правительство во главе с немецкими социал-демократами призвало к перемирию и получило его 11 ноября. Его сменила Веймарская республика . [114] Те, кто выступал против, включая недовольных ветеранов, присоединились к разнообразным военизированным и подпольным политическим группам, таким как Фрайкор , Организация Консул и коммунисты.

Империя была федеративной парламентской конституционной монархией .

Федеральный совет ( Бундесрат ) осуществлял суверенитет над империей и был ее высшим органом власти. [115] Бундесрат был законодательным органом, который обладал правом законодательной инициативы (статья VII № 1) и, поскольку все законы требовали его согласия, мог фактически наложить вето на любой законопроект, поступавший из Рейхстага ( статья V). [116] Бундесрат мог устанавливать руководящие принципы и вносить организационные изменения в исполнительную власть, выступать в качестве верховного арбитра в административных спорах между землями и служить конституционным судом для земель , в которых не было конституционного суда (статья LXXVI). [116] Он состоял из представителей, которые назначались правительствами земель и отчитывались перед ними. [117]

Имперский рейхстаг ( Reichstag ) был законодательным органом, избираемым всеобщим мужским голосованием, который фактически служил парламентом. Он имел право предлагать законопроекты и, с согласия Бундесрата , ежегодно утверждать государственный бюджет и военный бюджет на периоды в семь лет до 1893 года, а затем на пять лет. Все законы требовали одобрения Рейхстага для принятия. [118] После конституционных реформ октября 1918 года рейхсканцлер, посредством изменения статьи XV, стал зависеть от доверия Рейхстага, а не императора. [119]

Император ( кайзер ) был главой государства Империи — он не был правителем. Он назначал канцлера, обычно человека, способного завоевать доверие Рейхстага . Канцлер, консультируясь с императором, определял общие направления политики правительства и представлял их Рейхстагу . [ 118 ] По совету канцлера император назначал министров и — по крайней мере формально — всех других имперских должностных лиц. Все акты императора, за исключением военных директив [120], требовали контрассигнации канцлера (статья XVII). Император также отвечал за подписание законопроектов, объявление войны (что требовало согласия Бундесрата ) , ведение переговоров о мире, заключение договоров и созыв и закрытие сессий Бундесрата и Рейхстага ( статьи XI и XII). Император был главнокомандующим армией Империи (статья LXIII) и флотом (статья LIII); [116] При осуществлении своих военных полномочий он имел полную власть .

Канцлер был главой правительства , возглавлял Бундесрат и Имперское правительство, руководил законотворческим процессом и скреплял подписью все акты императора (за исключением военных директив). [118]

До объединения территория Германии (исключая Австрию и Швейцарию) состояла из 27 государств-участников. Эти государства состояли из королевств, великих герцогств, герцогств, княжеств, свободных ганзейских городов и одной имперской территории. Вольные города имели республиканскую форму правления на государственном уровне, хотя Империя в целом была образована как монархия, как и большинство государств. Пруссия была крупнейшим из государств-участников, охватывая две трети территории империи.

Некоторые из этих государств получили суверенитет после распада Священной Римской империи и были фактически суверенными с середины 1600-х годов. Другие были созданы как суверенные государства после Венского конгресса в 1815 году. Территории не обязательно были смежными — многие существовали в нескольких частях в результате исторических приобретений или, в некоторых случаях, разделов правящих семей. Некоторые из изначально существовавших государств, в частности Ганновер, были упразднены и аннексированы Пруссией в результате войны 1866 года.

Каждый компонент Германской империи посылал своих представителей в Федеральный совет ( Бундесрат ) и, через одномандатные округа, в Имперский сейм ( Рейхстаг ). Отношения между имперским центром и компонентами империи были несколько подвижными и развивались на постоянной основе. Степень, в которой германский император мог, например, вмешиваться в случаях спорного или неясного престолонаследия, время от времени вызывала много споров — например, во время кризиса наследования в Липпе-Детмольде .

Необычно для федерации или национального государства, германские государства сохраняли ограниченную автономию в иностранных делах и продолжали обмениваться послами и другими дипломатами (как друг с другом, так и напрямую с иностранными государствами) на протяжении всего существования Империи. Вскоре после провозглашения Империи Бисмарк ввел конвенцию, по которой его суверен будет отправлять и принимать послов в другие германские государства только как король Пруссии, в то время как посланники из Берлина, отправляемые в иностранные государства, всегда получали верительные грамоты от монарха в его качестве германского императора. Таким образом, прусское министерство иностранных дел в значительной степени было уполномочено управлять отношениями с другими германскими государствами, в то время как имперское министерство иностранных дел управляло внешними связями Германии.

Около 92% населения говорили на немецком как на родном языке. Единственным языком меньшинства со значительным числом носителей (5,4%) был польский (цифра, которая возрастает до более чем 6%, если включить родственные кашубские и мазурские языки).

Негерманские германские языки (0,5%), такие как датский , голландский и фризский , были распространены на севере и северо-западе империи, недалеко от границ с Данией , Нидерландами , Бельгией и Люксембургом . Нижненемецкий язык был распространен по всей северной Германии и, хотя лингвистически отличался от верхненемецкого ( Hochdeutsch ), как от голландского и английского, считался «немецким», отсюда и его название. На датском и фризском языках преимущественно говорили на севере прусской провинции Шлезвиг-Гольштейн , а на голландском — в западных приграничных районах Пруссии ( Ганновер , Вестфалия и Рейнская провинция ).

Польский и другие западнославянские языки (6,28%) были распространены в основном на востоке. [c]

Немногие (0,5%) говорили по-французски, подавляющее большинство из них проживало в Рейхсланд -Лотрингии , где франкоговорящие составляли 11,6% от общей численности населения.

В 1860-х годах Россия отменила привилегии для немецких эмигрантов и оказала давление на немецких иммигрантов, чтобы они ассимилировались. Большинство немецких эмигрантов покинули Россию после начала века. Некоторые из этих этнических немцев иммигрировали в Германию. [123]

В целом религиозная демография раннего Нового времени почти не изменилась. Тем не менее, были почти полностью католические районы (Нижняя и Верхняя Бавария, Северная Вестфалия, Верхняя Силезия и т. д.) и почти полностью протестантские районы (Шлезвиг-Гольштейн, Померания, Саксония и т. д.). Конфессиональные предрассудки, особенно по отношению к смешанным бракам, все еще были распространены. Постепенно, посредством внутренней миграции, религиозное смешение становилось все более распространенным. На восточных территориях конфессия воспринималась почти однозначно как связанная с этнической принадлежностью, и уравнение «протестант = немец, католик = поляк» считалось верным. В районах, затронутых иммиграцией в Рурской области и Вестфалии, а также в некоторых крупных городах, религиозный ландшафт существенно изменился. Это было особенно актуально в преимущественно католических районах Вестфалии, которые изменились благодаря протестантской иммиграции из восточных провинций.

Политически конфессиональное разделение Германии имело значительные последствия. В католических областях Центристская партия имела большой электорат. С другой стороны, социал-демократы и Свободные профсоюзы обычно получали едва ли какие-либо голоса в католических областях Рура. Это начало меняться с секуляризацией, возникшей в последние десятилетия Германской империи.

В заморской колониальной империи Германии миллионы подданных практиковали различные местные религии в дополнение к христианству. Более двух миллионов мусульман также жили под немецким колониальным правлением, в основном в Германской Восточной Африке . [124]

Поражение и последствия Первой мировой войны , а также наказания, наложенные Версальским договором, сформировали позитивную память об Империи, особенно среди немцев, которые не доверяли Веймарской республике и презирали ее. Консерваторы, либералы, социалисты, националисты, католики и протестанты — все имели свои собственные интерпретации, что привело к нестабильному политическому и социальному климату в Германии после распада империи.

При Бисмарке, наконец, было достигнуто объединенное немецкое государство, но оно оставалось государством с доминированием Пруссии и не включало немецкую Австрию, как желали пангерманские националисты. Влияние прусского милитаризма , колониальные усилия империи и ее энергичная, конкурентоспособная промышленная мощь — все это вызвало неприязнь и зависть других стран. Германская империя провела ряд прогрессивных реформ, таких как первая в Европе система социального обеспечения и свобода прессы. Также существовала современная система выборов в федеральный парламент, Рейхстаг, в котором каждый взрослый мужчина имел один голос. Это позволило социал-демократам и католической Центристской партии играть значительную роль в политической жизни империи, несмотря на продолжающуюся враждебность прусских аристократов.

Эпоха Германской империи хорошо помнят в Германии как эпоху великого культурного и интеллектуального расцвета. Томас Манн опубликовал свой роман «Будденброки» в 1901 году. Теодор Моммзен получил Нобелевскую премию по литературе годом позже за свою историю Рима. Такие художники, как группы « Der Blaue Reiter» и «Die Brücke», внесли значительный вклад в современное искусство. Турбинный завод AEG в Берлине, построенный Петером Беренсом в 1909 году, стал важной вехой в классической современной архитектуре и выдающимся примером зарождающегося функционализма. Социальные, экономические и научные успехи этой эпохи Gründerzeit , или основополагающей эпохи, иногда приводили к тому, что эпоху Вильгельма считали золотым веком .

В области экономики « Kaiserzeit » заложил основу статуса Германии как одной из ведущих экономических держав мира. Особенно способствовали этому процессу металлургическая и угольная промышленность Рура , Саара и Верхней Силезии . Первый автомобиль был построен Карлом Бенцем в 1886 году. Огромный рост промышленного производства и промышленного потенциала также привел к быстрой урбанизации Германии, что превратило немцев в нацию городских жителей. Более 5 миллионов человек покинули Германию и переехали в Соединенные Штаты в течение 19 века. [125]

Многие историки подчеркивали центральное значение немецкого Sonderweg или «особого пути» (или «исключительности») как корня нацизма и немецкой катастрофы в 20 веке. Согласно историографии Коцки (1988), процесс строительства нации сверху имел очень печальные долгосрочные последствия. С точки зрения парламентской демократии парламент оставался слабым, партии были раздроблены, и существовал высокий уровень взаимного недоверия. Нацисты опирались на нелиберальные, антиплюралистические элементы политической культуры Веймара. Юнкерская элита (крупные землевладельцы на востоке) и старшие государственные служащие использовали свою огромную власть и влияние вплоть до двадцатого века, чтобы сорвать любое движение к демократии. Они сыграли особенно негативную роль в кризисе 1930–1933 годов. Акцент Бисмарка на военной силе усилил голос офицерского корпуса, который сочетал передовую модернизацию военной технологии с реакционной политикой. Растущая элита высшего среднего класса в деловом, финансовом и профессиональном мире, как правило, принимала ценности старых традиционных элит. Германская империя была для Ганса-Ульриха Велера странной смесью весьма успешной капиталистической индустриализации и социально-экономической модернизации, с одной стороны, и выживших доиндустриальных институтов, властных отношений и традиционных культур, с другой. Велер утверждает, что это породило высокую степень внутреннего напряжения, которое привело, с одной стороны, к подавлению социалистов, католиков и реформаторов, а с другой стороны, к крайне агрессивной внешней политике. По этим причинам Фриц Фишер и его ученики подчеркивали главную вину Германии в развязывании Первой мировой войны. [126]

Ганс-Ульрих Велер , лидер Билефельдской школы социальной истории, относит истоки пути Германии к катастрофе к 1860–1870-м годам, когда произошла экономическая модернизация, но не произошла политическая модернизация, и старая прусская сельская элита сохранила жесткий контроль над армией, дипломатией и государственной службой. Традиционное, аристократическое, досовременное общество боролось с зарождающимся капиталистическим, буржуазным, модернизирующимся обществом. Признавая важность модернизационных сил в промышленности, экономике и культурной сфере, Велер утверждает, что реакционный традиционализм доминировал в политической иерархии власти в Германии, а также в социальных менталитетах и в классовых отношениях ( Klassenhabitus ). Катастрофическая немецкая политика между 1914 и 1945 годами интерпретируется в терминах отложенной модернизации ее политических структур. В основе интерпретации Велера лежит его трактовка «среднего класса» и «революции», каждая из которых сыграла важную роль в формировании 20-го века. Исследование Велера нацистского правления сформировано его концепцией «харизматического господства», которая в значительной степени фокусируется на Гитлере. [127]

Историографическая концепция немецкого особого пути имела бурную историю. Ученые 19-го века, подчеркивавшие отдельный немецкий путь к современности, видели в нем положительный фактор, отличавший Германию от «западного пути», типичного для Великобритании. Они подчеркивали сильное бюрократическое государство, реформы, инициированные Бисмарком и другими сильными лидерами, прусский этос служения, высокую культуру философии и музыки и пионерство Германии в области социального государства. В 1950-х годах историки в Западной Германии утверждали, что особый путь привел Германию к катастрофе 1933–1945 годов. Особые обстоятельства немецких исторических структур и опыта интерпретировались как предпосылки, которые, хотя и не стали прямой причиной национал-социализма, препятствовали развитию либеральной демократии и способствовали подъему фашизма. Парадигма Sonderweg дала толчок по крайней мере трем направлениям исследований в немецкой историографии: « длинный 19 век », история буржуазии и сравнение с Западом. После 1990 года возросшее внимание к культурным измерениям и сравнительной и реляционной истории переместило немецкую историографию к другим темам, при этом гораздо меньше внимания уделялось Sonderweg . Хотя некоторые историки отказались от тезиса Sonderweg , они не предоставили общепринятой альтернативной интерпретации. [128]

Германская империя имела две вооружённые силы:

Помимо современной Германии, значительные части территорий, входивших в состав Германской империи, теперь принадлежат нескольким другим современным европейским странам.

Информационные заметки

Цитаты

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Einst Hatten die Deutschen das drittgrößte Kolonialreich...

Историография

Первичные источники