Форт-Уэрт — город в американском штате Техас и административный центр округа Таррант , занимающий площадь около 350 квадратных миль (910 км 2 ) в округах Дентон , Джонсон , Паркер и Уайз . Согласно оценке переписи населения США 2023 года, население Форт-Уэрта составляло 978 468 человек, что делает его пятым по численности населения городом в штате и 12-м по численности населения в Соединенных Штатах . [8] [9] Форт-Уэрт — второй по величине город в метрополии Даллас-Форт-Уэрт , которая является четвертой по численности населения городской агломерацией в США и самой густонаселенной в Техасе . [10] [11]

Город Форт-Уэрт был основан в 1849 году как армейский форпост на утесе с видом на реку Тринити . [12] Форт-Уэрт исторически был центром торговли скотом породы техасский лонгхорн . [12] Он по-прежнему сохраняет свое западное наследие и традиционную архитектуру и дизайн. [13] [14] USS Fort Worth (LCS-3) — первый корабль ВМС США, названный в честь города. [15] Соседний Даллас удерживал большинство населения с тех пор, как велись записи, однако Форт-Уэрт стал одним из самых быстрорастущих городов в Соединенных Штатах в начале 21-го века, почти удвоив свое население с 2000 года.

Форт-Уэрт является местом проведения Международного конкурса пианистов имени Ван Клиберна и нескольких музеев, спроектированных современными архитекторами. Художественный музей Кимбелла был спроектирован Луисом Каном , а пристройка спроектирована Ренцо Пиано . [16] Музей современного искусства Форт-Уэрта был спроектирован Тадао Андо . Музей американского искусства Амона Картера , спроектированный Филипом Джонсоном , представляет американское искусство. Музей Сида Ричардсона , перепроектированный Дэвидом М. Шварцем , имеет коллекцию западного искусства в США, подчеркивая творчество Фредерика Ремингтона и Чарльза Рассела . Музей науки и истории Форт-Уэрта был спроектирован Рикардо Легорретой из Мексики.

Форт-Уэрт является местом расположения нескольких университетских сообществ: Техасский христианский университет , Техасский Уэслианский университет , Центр медицинских наук Университета Северного Техаса и Юридическая школа Техасского университета A&M . Несколько транснациональных корпораций, включая Bell Textron , American Airlines и BNSF Railway , имеют штаб-квартиры в Форт-Уэрте.

Договор о форте Берд между Республикой Техас и несколькими индейскими племенами был подписан в 1843 году в форте Берд в современном Арлингтоне, штат Техас . [17] [18] Статья XI договора предусматривала, что никто не может «переходить линию торговых домов» (на границе территории индейцев) без разрешения президента Техаса , и не может проживать или оставаться на территории индейцев. Эти «торговые дома» были позже созданы на стыке Клир-Форк и Вест-Форк реки Тринити в современном Форт-Уэрте. [19]

Линия из семи армейских постов была создана в 1848–1849 годах после Мексиканской войны для защиты поселенцев Техаса вдоль западной американской границы и включала Форт-Уорт, Форт-Грэхэм , Форт-Гейтс , Форт-Кроган , Форт-Мартин Скотт , Форт-Линкольн и Форт-Дункан . [20] Первоначально 10 фортов были предложены генерал-майором Уильямом Дженкинсом Уортом (1794–1849), который командовал Департаментом Техаса в 1849 году. В январе 1849 года Уорт предложил линию из 10 фортов, чтобы обозначить западную границу Техаса от Игл-Пасс до слияния Уэст-Форк и Клир-Форк реки Тринити . Месяц спустя Уорт умер от холеры в Южном Техасе. [20]

Генерал Уильям С. Харни принял командование Департаментом Техаса и приказал майору Рипли А. Арнольду (рота F, Второй драгунский полк Соединенных Штатов) [20] найти новое место для форта недалеко от Уэст-Форк и Клир-Форк. 6 июня 1849 года Арнольд, по совету Миддлтона Тейта Джонсона, разбил лагерь на берегу реки Тринити и назвал пост Кэмп-Уорт в честь покойного генерала Уорта. В августе 1849 года Арнольд перенес лагерь на обращенный к северу утес, который возвышался над устьем Клир-Форк реки Тринити. Военное министерство Соединенных Штатов официально назвало пост Форт-Уорт 14 ноября 1849 года. [21] С момента своего основания город Форт-Уорт продолжает называться «там, где начинается Запад». [12]

Э. С. Террелл (1812–1905) из Теннесси утверждал, что был первым жителем Форт-Уэрта. [22] Форт был затоплен в первый год и перенесен на вершину утеса; нынешнее здание суда было построено на этом месте. Форт был заброшен 17 сентября 1853 года. [20] Никаких следов от него не сохранилось.

Будучи остановкой на легендарной тропе Чисхолм , Форт-Уорт был стимулирован бизнесом по перегону скота и стал шумным, шумным городом. Миллионы голов скота гнали на север на рынок по этой тропе. Форт-Уорт стал центром перегона скота , а позже и индустрии ранчо . Ему дали прозвище Каутаун. [23]

Во время Гражданской войны в США Форт-Уэрт страдал от нехватки денег, продовольствия и припасов. Население сократилось до 175 человек, но начало восстанавливаться во время Реконструкции . К 1872 году Джейкоб Сэмюэлс, Уильям Джесси Боаз и Уильям Генри Дэвис открыли универсальные магазины. В следующем году Хлебер М. Ван Зандт основал Tidball, Van Zandt, and Company, которая в 1884 году стала Fort Worth National Bank.

В 1875 году Dallas Herald опубликовала статью бывшего юриста Форт-Уэрта Роберта Э. Коуарта, который писал, что сокращение населения Форт-Уэрта, вызванное экономической катастрофой и суровой зимой 1873 года, нанесло серьезный удар по скотоводству. В дополнение к замедлению из-за остановки железной дорогой прокладки путей в 30 милях (48 км) от Форт-Уэрта, Коуарт сказал, что Форт-Уэрт был настолько медлительным, что он увидел пантеру, спящую на улице у здания суда. Несмотря на преднамеренное оскорбление, название Panther City было с энтузиазмом принято, когда в 1876 году Форт-Уэрт восстановился экономически. [24] Многие предприятия и организации продолжают использовать слово Panther в своем названии. Пантера изображена наверху значков полицейского управления. [25]

Традиция «Города пантер» также сохранилась в названиях и дизайне некоторых географических и архитектурных объектов города, таких как Остров пантер (на реке Тринити), Здание Флэт-Айрон, Центральный вокзал Форт-Уэрта , а также в двух или трех статуях «Спящей пантеры».

В 1876 году Техасско-Тихоокеанская железная дорога наконец была достроена до Форт-Уэрта, что стимулировало бум и превратило скотные дворы Форт-Уэрта в главный центр оптовой торговли скотом. [26] Мигранты с опустошенного войной Юга продолжали увеличивать население, а небольшие общественные фабрики и мельницы уступили место более крупным предприятиям. Недавно названный «Королевой города прерий», [27] Форт-Уэрт снабжал региональный рынок через растущую транспортную сеть.

Форт-Уэрт стал самой западной железнодорожной станцией и транзитным пунктом для перевозки скота. Лувилл Найлз, бизнесмен из Бостона , штат Массачусетс , и главный акционер компании Fort Worth Stockyards Company, считается тем, что привел на скотобазы две крупнейшие в то время компании по упаковке мяса , Armour и Swift . [28]

С наступлением бума появилось множество развлечений и связанных с ними проблем. Форт-Уорт умел отделять скотоводов от их денег. Ковбои в полной мере воспользовались своим последним соприкосновением с цивилизацией перед долгой поездкой по тропе Чисхолм из Форт-Уорта на север в Канзас . Они запасались провизией у местных торговцев, посещали салуны, чтобы немного поиграть и покутить, затем ехали на север со своим скотом, только чтобы снова повеселиться на обратном пути. Город вскоре стал домом для « Адского полуакра », крупнейшего собрания салунов, танцевальных залов и публичных домов к югу от Додж-Сити (северной конечной точки тропы Чисхолм), что дало Форт-Уорту прозвище «Париж равнин». [29] [30]

Некоторые части города были закрыты для законных граждан. Стрельба, поножовщина, грабежи и драки стали ежевечерним явлением. К ковбоям присоединилась разношерстная группа охотников на бизонов, стрелков, авантюристов и мошенников. Адский полуакр (также известный как просто «Акр») расширялся по мере того, как в город приезжало все больше людей. Иногда Акр называли «кровавым Третьим округом» после того, как в 1876 году он был назначен одним из трех политических округов города. К 1900 году Акр охватывал четыре главных городских магистрали с севера на юг. [31] Местные жители были встревожены этой деятельностью, избрав Тимоти Исайю «Длинноволосого Джима» Кортрайта в 1876 году городским маршалом с мандатом на ее усмирение.

Кортрайт иногда собирал и сажал в тюрьму 30 человек в субботу вечером, но позволял игрокам работать, так как они привлекали деньги в город. Узнав, что грабители поездов и дилижансов, такие как банда Сэма Басса , использовали этот район в качестве укрытия, он усилил меры по обеспечению соблюдения закона, но некоторые бизнесмены выступали против слишком большого количества ограничений в этом районе, поскольку это плохо сказывалось на законном бизнесе. Постепенно ковбои начали избегать этого района; по мере того, как бизнес страдал, город смягчал свое сопротивление. Кортрайт потерял свой пост в 1879 году. [31]

Несмотря на крестоносных мэров, таких как HS Broiles , и редакторов газет, таких как BB Paddock, Acre выжил, потому что он приносил доход городу (все это незаконно) и волнение для посетителей. Давние жители Форт-Уорта утверждали, что место никогда не было таким диким, как его репутация, но в 1880-х годах Форт-Уорт был регулярной остановкой в «круговороте азартных игр» Бэта Мастерсона , Дока Холлидея и братьев Эрп (Уайетта, Моргана и Вирджила). [31] Джеймс Эрп , старший из его братьев, жил со своей женой в Форт-Уорте в этот период; их дом находился на краю Hell's Half Acre, на 9-й и Калхун. Он часто работал баром в салуне Cattlemen's Exchange в «верхней» части города. [32]

Граждане, выступавшие за реформы, возражали против танцевальных залов , где мужчины и женщины смешивались; напротив, в салунах и игорных домах клиентами были в основном мужчины.

В конце 1880-х годов мэр Бройлс и окружной прокурор Р. Л. Карлок инициировали кампанию реформ. В публичной перестрелке 8 февраля 1887 года Джим Кортрайт был убит на Мейн-стрит Люком Шортом , который утверждал, что он был «королем игроков Форт-Уэрта». [31] Поскольку Кортрайт был популярен, когда Шорта посадили в тюрьму за его убийство, поползли слухи о его линчевании. Хороший друг Шорта Бэт Мастерсон пришел вооруженным и провел ночь в его камере, чтобы защитить его.

Первая кампания по запрету алкоголя в Техасе была организована в Форт-Уэрте в 1889 году, что позволило вести в этом районе другие виды бизнеса и жилую застройку. Другим изменением стал приток чернокожих и афроамериканских жителей. Исключенные из деловой части города и более дорогих жилых районов государственной сегрегацией , чернокожие граждане города поселились в южной части города. Популярность и прибыльность Акра снизились, и на улицах стало больше бездомных и бродяг. К 1900 году большинство танцевальных залов и игроков исчезли. Дешевые варьете и проституция стали основными формами развлечений. Некоторые прогрессивные политики начали наступление, чтобы найти и отменить эти предполагаемые «пороки» в рамках более широкого пакета реформ Прогрессивной эры . [31]

_(14770397571).jpg/440px-Book_of_Texas_(1916)_(14770397571).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Partial_View_of_Business_Section_(20106688).jpg)

В 1911 году преподобный Дж. Фрэнк Норрис начал наступление против азартных игр на ипподроме в Baptist Standard и использовал кафедру Первой баптистской церкви Форт-Уэрта для нападок на порок и проституцию. Когда он начал связывать некоторых бизнесменов Форт-Уэрта с собственностью в Акре и объявлять их имена со своей кафедры, битва разгорелась. 4 февраля 1912 года церковь Норриса сгорела дотла; тем же вечером его враги бросили на его крыльцо связку горящих промасленных тряпок, но огонь был потушен и причинил минимальный ущерб. Месяц спустя поджигателям удалось сжечь пасторский дом . В сенсационном судебном процессе, длившемся месяц, Норрис был обвинен в лжесвидетельстве и поджоге в связи с двумя пожарами. Его оправдали, но его постоянные нападения на Акр не приносили особых результатов вплоть до 1917 года. Новая городская администрация и федеральное правительство, рассматривавшее Форт-Уэрт как потенциальное место для крупного военного тренировочного лагеря , объединили усилия с баптистским проповедником, чтобы положить конец нападению на Акр.

Полицейское управление собрало статистику, показывающую, что 50% насильственных преступлений в Форт-Уэрте произошло в Акре, что подтвердило мнение уважаемых граждан об этом районе. После того, как в 1917 году на окраине Форт-Уэрта был расположен лагерь Боуи (учебный центр армии США времен Первой мировой войны), военные ввели военное положение для регулирования проституток и барменов Акре. Штрафы и суровые тюремные сроки ограничили их деятельность. К тому времени, когда Норрис провел имитационный похоронный парад, чтобы «похоронить Джона Ячменное Зерно » в 1919 году, Акр стал частью истории Форт-Уэрта. Это название продолжает ассоциироваться с южной оконечностью Форт-Уэрта. [33]

В 1921 году забастовка профсоюза, состоявшего только из белых, на мясокомбинате Fort Worth, Swift & Co. в Niles City Stockyards. Владельцы попытались заменить их чернокожими штрейкбрехерами . Во время профсоюзных протестов штрейкбрехер-афроамериканец Фред Рауз был линчеван на дереве на углу NE 12th Street и Samuels Avenue. После того, как его повесили, белая толпа изрешетила его изуродованное тело выстрелами. [34]

21 ноября 1963 года президент Джон Ф. Кеннеди прибыл в Форт-Уэрт, выступил на следующее утро на утреннем заседании Торговой палаты Форт-Уэрта, а затем отправился в Даллас, где в тот же день был убит.

Когда в начале 20 века в Западном Техасе начала бить нефть , а затем снова в конце 1970-х годов, Форт-Уорт оказался в центре бума. К июлю 2007 года достижения в технологии горизонтального бурения сделали огромные запасы природного газа в сланцевом месторождении Барнетт доступными прямо под городом, [35] помогая многим жителям получать чеки на роялти за свои права на добычу полезных ископаемых. Сегодня город Форт-Уорт и многие жители сталкиваются с преимуществами и проблемами, связанными с подземными запасами природного газа. [36] [37]

28 марта 2000 года в 18:15 торнадо F3 обрушился на центр Форт-Уэрта, серьезно повредив многие здания. Одним из наиболее пострадавших сооружений стала башня Bank One Tower, которая была одной из доминант горизонта Форт-Уэрта и на верхнем этаже которой находился популярный ресторан «Reata». С тех пор она была переоборудована в высококлассные кондоминиумы и официально переименована в «Башню». Это был первый крупный торнадо , обрушившийся на Форт-Уэрт с начала 1940-х годов. [38]

С 2000 по 2006 год Форт-Уэрт был самым быстрорастущим крупным городом в Соединенных Штатах; [39] он был признан одним из «Самых пригодных для жизни сообществ Америки». [40] Помимо обратной миграции , многие афроамериканцы переезжают в Форт-Уэрт из-за его доступной стоимости жизни и возможностей трудоустройства. [41]

В 2020 году мэр Форт-Уэрта объявил о продолжении роста города до 20,78%. [42] Бюро переписи населения США также отметило начало большей диверсификации города с 2014 по 2018 год. [43]

11 февраля 2021 года на шоссе I-35W произошло столкновение с участием 133 автомобилей и грузовиков из-за ледяного дождя, оставившего лед. В результате столкновения погибло по меньшей мере шесть человек и множество получили ранения. [44] [45] [46]

Форт-Уэрт расположен в Северном Техасе и имеет в целом влажный субтропический климат. [47] Он является частью региона Кросс-Тимберс ; [48] этот регион является границей между более лесистыми восточными частями и холмами и прериями центральной части. В частности, город является частью экорегиона Гранд-Прери в Кросс-Тимберс. По данным Бюро переписи населения США , город имеет общую площадь 349,2 квадратных миль (904 км 2 ), из которых 342,2 квадратных миль (886 км 2 ) занимают сушу и 7,0 квадратных миль (18 км 2 ) покрыты водой. Это главный город в метроплексе Даллас-Форт-Уэрт и второй по величине город по численности населения.

Город Форт-Уэрт не является полностью непрерывным и имеет несколько анклавов, практических анклавов, полуанклавов и городов, которые в противном случае полностью или почти окружены им, в том числе: Westworth Village , River Oaks , Saginaw , Blue Mound , Benbrook , Everman , Forest Hill , Edgecliff Village , Westover Hills , White Settlement , Sansom Park , Lake Worth , Lakeside и Haslet .

В Форт-Уэрте имеется более 1000 скважин природного газа (по состоянию на декабрь 2009 года), которые вскрывают сланец Барнетт. [49] Каждая скважина представляет собой голый участок гравия размером 2–5 акров (8 100–20 200 м 2 ). Поскольку городские постановления разрешают им во всех категориях зонирования, включая жилые, скважины можно найти в самых разных местах. Некоторые скважины окружены каменными заборами, но большинство защищено сеткой цепи.

В 1914 году на западном рукаве реки Тринити, в 7 милях (11 км) от города, было построено крупное водохранилище с объемом хранения 33 495 акров футов воды. [50] Озеро, образованное этой плотиной, известно как озеро Уорт .

.jpg/440px-Fort_Worth_June_2016_46_(Sundance_Square_Plaza).jpg)

Центр Форт-Уэрта состоит из многочисленных районов, включающих коммерческие и торговые, жилые и развлекательные. Среди них Sundance Square — район смешанного использования, популярный среди любителей ночной жизни и развлечений. Bass Performance Hall находится на Sundance Square. Соседний Upper West Side также является заметным районом в центре Форт-Уэрта. Он ограничен примерно Henderson Street на востоке, Trinity River на западе, Interstate 30 на юге и White Settlement Road на севере. Район содержит несколько небольших и средних офисных зданий и городских жилых домов, но очень мало розничной торговли.

Стокьярдс Форт-Уэрта — национальный исторический район . [51] Стокьярдс когда-то был одним из крупнейших рынков скота в Соединенных Штатах и играл важную роль в раннем росте города. [52] Сегодня этот район характеризуется множеством баров, ресторанов и известных кантри-музыкальных заведений, таких как Billy Bob's . Знаменитый шеф-повар Форт-Уэрта Тим Лав из Iron Chef America и Top Chef Masters управлял несколькими ресторанами в этом районе. [53] [54] На станции Стокьярдс есть торговый центр, а через железную дорогу Грейпвайн Винтаж проходит поезд , который соединяется с центром Грейпвайн . [55] В Колизее Каутауна каждую неделю проходит родео, а также там находится Зал славы техасских ковбоев. [56] [57] Самый большой в мире хонки-тонк также находится в Стокьярдс в Билли Бобе . [58] Форт-Уэрт Стокьярдс — единственный крупный город, где ежедневно проводится перегон скота. [59]

Tanglewood состоит из земли в низинных районах вдоль рукава реки Тринити и находится примерно в пяти милях к юго-западу от центрального делового района Форт-Уэрта. [60] [61] Район Tanglewood находится в пределах двух обследований. Западная часть пристройки является частью обследования Феликса Г. Бисли 1854 года, а восточная часть, вдоль рукава реки, является обследованием Джеймса Говарда 1876 года. Первоначальный подход к району Tanglewood состоял из двухколейной грунтовой дороги, которая сейчас называется Bellaire Drive South. До времени развития дети любили плавать в реке в глубокой яме, которая находилась там, где сейчас находится мост на Bellaire Drive South, недалеко от торгового центра Trinity Commons. Части Tanglewood, которые сейчас являются Bellaire Park Court, Marquette Court и Autumn Court, изначально были молочной фермой.

Центр Форт-Уэрта с его уникальной деревенской архитектурой в основном известен своими зданиями в стиле ар-деко . Здание суда округа Таррант было создано в американском стиле боз-ар , который был смоделирован по образцу здания Капитолия штата Техас . Большинство сооружений вокруг площади Санданс в центре города сохранили свои фасады начала 20-го века . Несколько кварталов вокруг площади Санданс подсвечиваются ночью рождественскими огнями круглый год.

В Форт-Уэрте влажный субтропический климат (Cfa) согласно системе классификации климата Кёппена , и он находится в зоне морозостойкости USDA 8a. [62] Для этого региона характерны очень жаркое, влажное лето и мягкая или прохладная зима. Самый жаркий месяц года — август, когда средняя максимальная температура составляет 96 °F (35,6 °C), а средняя ночная минимальная температура составляет 75 °F (23,9 °C), что дает среднюю температуру 85 °F (29,4 °C). [63] Самый холодный месяц года — январь, когда средняя максимальная температура составляет 56 °F (13,3 °C), а средняя минимальная температура составляет 35 °F (1,7 °C). [63] Средняя температура в январе составляет 46 °F (8 °C). [63] Самая высокая температура, когда-либо зарегистрированная в Форт-Уэрте, составила 113 °F (45,0 °C) 26 июня 1980 года во время Великой волны тепла 1980 года и 27 июня 1980 года . [64] Самая низкая температура, когда-либо зарегистрированная в Форт-Уэрте, составила −8 °F (−22,2 °C) 12 февраля 1899 года. Из-за своего расположения в Северном Техасе Форт-Уэрт очень подвержен грозам типа «суперячейка» , которые вызывают крупный град и могут вызывать торнадо .

Среднегодовое количество осадков для Форт-Уэрта составляет 34,01 дюйма (863,9 мм). [63] Самый влажный месяц года — май, когда выпадает в среднем 4,58 дюйма (116,3 мм) осадков. [63] Самый сухой месяц года — январь, когда выпадает всего 1,70 дюйма (43,2 мм) осадков. [63] Самым сухим календарным годом с начала ведения записей был 1921 год с 17,91 дюйма (454,9 мм), а самым влажным — 2015 год с 62,61 дюйма (1590,3 мм). Самым влажным календарным месяцем был апрель 1922 года с 17,64 дюйма (448,1 мм), включая 8,56 дюйма (217,4 мм) 25 апреля.

Среднегодовое количество выпавшего снега в Форт-Уэрте составляет 2,6 дюйма (66,0 мм). [65] Наибольшее количество выпавшего снега за один месяц составило 13,5 дюймов (342,9 мм) в феврале 1978 года, а наибольшее количество за сезон — 17,6 дюймов (447,0 мм) в 1977/1978 годах.

Офис Национальной метеорологической службы , обслуживающий метроплекс Даллас–Форт-Уэрт, находится в северо-восточной части Форт-Уэрта. [66]

Форт-Уэрт — самый густонаселенный город в округе Таррант и второе по численности населения сообщество в агломерации Даллас-Форт-Уэрт . Его столичная статистическая область охватывает четверть населения Техаса и является крупнейшей в Южных США и Техасе, за ней следует столичная область Хьюстон-Вудлендс-Шугар-Ленд . По оценкам переписи населения Американского обследования населения 2018 года, в городе Форт-Уэрт проживало около 900 000 жителей. [43] В 2019 году она выросла до оценочных 909 585 человек. По переписи населения США 2020 года население Форт-Уэрта составляло 918 915 человек, а по оценкам переписи 2022 года — около 956 709 жителей. [9]

По оценкам переписи 2018 года насчитывалось 337 072 единиц жилья, 308 188 домохозяйств и 208 389 семей. [71] Средний размер домохозяйства составлял 2,87 человека на домохозяйство, а средний размер семьи — 3,50. В Форт-Уэрте уровень жилья, занимаемого собственниками, составлял 56,4%, а уровень жилья, занимаемого арендаторами, — 43,6%. Медианный доход в 2018 году составлял 58 448 долларов, а средний доход — 81 165 долларов. [72] Доход на душу населения в городе составлял 29 010 долларов. [73] Примерно 15,6% жителей Форт-Уэрта жили на уровне или ниже черты бедности. [74]

По оценкам переписи населения Американского обследования населения 2010 года, насчитывалось 291 676 единиц жилья, [75] 261 042 домохозяйства и 174 909 семей. [76] В Форт-Уэрте средний размер домохозяйства составлял 2,78, а средний размер семьи — 3,47. В общей сложности 92 952 домохозяйства имели детей в возрасте до 18 лет, проживающих с ними. В 2010 году было 5,9% домохозяйств с не состоящими в браке партнерами противоположного пола и 0,5% домохозяйств с не состоящими в браке партнерами одного пола. Уровень жилья, занимаемого собственниками, в Форт-Уэрте составлял 59,0%, а уровень жилья, занимаемого арендаторами, — 41,0%. Медианный доход домохозяйства Форт-Уэрта составлял 48 224 доллара, а средний показатель — 63 065 долларов. [77] По оценкам, 21,4% населения жили на уровне или ниже черты бедности. [78]

По данным переписи населения США 2010 года , расовый состав населения Форт-Уэрта был следующим: 61,1% белых ( неиспаноязычные белые : 41,7%), 18,9% черных или афроамериканцев , 0,6% коренных американцев , 3,7% азиатских американцев , 0,1% коренных гавайцев и других жителей островов Тихого океана , 34,1% испаноязычных или латиноамериканцев (любой расы) и 3,1% представителей двух или более рас . В 2018 году 38,2% жителей Форт-Уэрта были неиспаноязычными белыми, 18,6% чернокожими или афроамериканцами, 0,4% американскими индейцами или коренными жителями Аляски, 4,8% азиатскими американцами, 0,1% жителями островов Тихого океана, 2,1% представителями двух или более рас и 35,5% испаноязычными или латиноамериканцами (любой расы), что ознаменовало эпоху диверсификации в пределах города. [43] [82]

Исследование определило Форт-Уэрт как один из самых разнообразных городов в Соединенных Штатах в 2019 году. [83] Для сравнения, в 1970 году Бюро переписи населения США сообщило, что население Форт-Уэрта составляет 72% неиспаноязычных белых, 19,9% афроамериканцев и 7,9% испаноязычных или латиноамериканцев. [81] К переписи 2020 года [ 79 ] продолжающийся рост населения стимулировал дальнейшую диверсификацию: 36,6% населения были неиспаноязычными белыми, 34,8% испаноязычными или латиноамериканцами любой расы и 19,2% черными или афроамериканцами; американцы азиатского происхождения увеличились до 5,1% населения, что отражает общенациональные демографические тенденции того времени. [84] [85] [86] В 2020 году в общей сложности 31 485 жителей были представителями двух или более рас . [79]

Расположенный в пределах Библейского пояса , христианство является крупнейшей коллективной религиозной группой в Форт-Уэрте и Метроплексе . Как в Далласе и округе Даллас , так и в Форт-Уэрте и округе Таррант проживает множество жителей -католиков . [87] [88] В целом, столичное подразделение Далласа метроплекса Даллас-Форт-Уэрт более религиозно разнообразно, чем Форт-Уэрт и его пригороды, особенно в округах главных городов.

.jpg/440px-Greater_Saint_James_Baptist_Church_Fort_Worth_Wiki_(1_of_1).jpg)

Старейшая постоянно действующая церковь в Форт-Уэрте — Первая христианская церковь , основанная в 1855 году. [89] Другие исторические церкви, продолжающие работать в городе, включают собор Святого Патрика (основан в 1888 году), баптистскую церковь Святого Джеймса на Второй улице (основана в 1895 году), баптистскую церковь Табернакль (построена в 1923 году), церковь Святой Марии Успенской (построена в 1924 году), католическую церковь и пасторский дом Богоматери Милосердия (построены в 1929 и 1911 годах) и церковь Morning Chapel CME (построена в 1934 году).

По данным Ассоциации архивов религиозных данных , в 2020 году католическая община округа Таррант насчитывала 359 705 человек [87] , и была крупнейшей христианской конфессией или традицией столичного округа Форт-Уэрт с 378 490 приверженцами. [90] По данным Римско-католической епархии Форт-Уэрта , по состоянию на 2023 год общее количество католиков составляло около 1 200 000 человек. [91] Среди других христианских организаций, олицетворяющих католичество , Ассоциация архивов религиозных данных сообщила, что Коптская православная церковь была крупнейшей восточнохристианской группой, за ней следовали Греческая православная архиепископия Америки и Православная церковь в Америке , Антиохийская православная архиепископия Северной Америки и Эритрейская православная церковь Тевахедо, насчитывающая в общей сложности 6 216 человек.

Южные баптисты, являющиеся домом для большой протестантской христианской общины, были второй по величине христианской конфессией в столичном округе Форт-Уэрта в 2020 году с 347 771 последователем. [90] Южные баптисты были разделены на более традиционалистских и консервативных Южных баптистов Техасской конвенции и теологически умеренную Баптистскую генеральную конвенцию Техаса ; Согласно данным Генеральной баптистской конвенции Техаса, по состоянию на 2023 год в окрестностях Форт-Уэрта насчитывалось 167 церквей. [92] Конвенция южных баптистов Техаса в 2023 году перечислила 117 церквей. [93] Другие известные баптистские конфессии, такие как Национальная миссионерская баптистская конвенция , Национальная баптистская конвенция , Национальная баптистская конвенция Америки , Братство баптистской церкви полного евангелия , Американская баптистская ассоциация и Национальная ассоциация баптистов свободной воли в совокупности насчитывали 51 261 церквей по данным исследования 2020 года.

Non- and inter-denominational churches dominated Fort Worth's religious landscape as the third-largest group of Christians. Having more than 289,554 adherents,[90] non/inter-denominational Christians represented the growing trend of ecumenism within the United States.[94][95] Methodists were the fourth-largest Christian group with more than 100,000 adherents of the United Methodist Church spread throughout Fort Worth's metropolitan division. The African Methodist Episcopal Church, Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and Free Methodist Church also formed a substantial portion of the area's Methodist population. Pentecostals, descended from the Wesleyan-Holiness movement of Methodists, formed the fifth-largest Christian constituency and primarily divided between the Assemblies of God USA and Church of God in Christ.

Among Fort Worther's non-Christian community, Islam and Judaism were the second- and third-largest religious communities.[90] According to the Association of Religion Data Archives, there were an estimated 37,488 Muslims and 2,413 Jews living in Fort Worth's vicinity, although the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life estimated 5,000 Jews in 2010.[96] Religions including Hinduism and Baha'i had a minuscule presence in the Fort Worth area according to the 2020 study, and Christendom remained more prevalent than in the Dallas metropolitan division.[90]

At its inception, Fort Worth relied on cattle drives that traveled the Chisholm Trail. Millions of cattle were driven north to market along this trail, and Fort Worth became the center of cattle drives, and later, ranching until the American Civil War. During the American Civil War, Fort Worth suffered shortages causing its population to decline. It recovered during the Reconstruction with general stores, banks, and "Hell's Half-Acre", a large collection of saloons and dance halls which increased business and criminal activity in the city. By the early 20th century the military used martial law to regulate Hell's Half-Acre's bartenders and prostitutes.

Since the late 20th century several major companies have been headquartered in Fort Worth. These include American Airlines Group (and subsidiaries American Airlines and Envoy Air), the John Peter Smith Hospital, Pier 1 Imports, Chip 1 Exchange,[97] RadioShack, Pioneer Corporation, Cash America International, GM Financial,[98] Budget Host, the BNSF Railway, and Bell Textron. Companies with a significant presence in the city are Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Lockheed Martin, GE Transportation, and Dallas-based telecommunications company AT&T. Metro by T-Mobile is also prominent in the city.

Building on its Frontier Western heritage and a history of strong local arts patronage, Fort Worth promotes itself as the "City of Cowboys and Culture".[99] Fort Worth has the world's first and largest indoor rodeo,[100] world-class museums, a calendar of festivals and a robust local arts scene. The Academy of Western Artists, based in Gene Autry, Oklahoma, presents its annual awards in Fort Worth in fields related to the American cowboy, including music, literature, and even chuck wagon cooking.[101] Fort Worth is also the 1931 birthplace of the Official State Music of Texas—Western Swing, which was created by Bob Wills and Milton Brown and their Light Crust Doughboys band in a ramshackle dancehall 4 miles west of downtown at the Crystal Springs Dance Pavilion.[102]

.jpg/440px-FW_Japanese_Gardens_2_(5569039869).jpg)

The Fort Worth Zoo is home to over 5,000 animals.

The Fort Worth Botanic Garden and the Botanical Research Institute of Texas are also in the city. For those interested in hiking, birding, or canoeing, the Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge in northwest Fort Worth is a 3,621-acre preserved natural area designated by the Department of the Interior as a National Natural Landmark Site in 1980. Established in 1964 as the Greer Island Nature Center and Refuge, it celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2014.[104] The Nature Center has a small, genetically pure bison herd, and native prairies, forests, and wetlands. It is one of the largest urban parks of its type in the United States.[105]

.jpg/440px-Fort_Worth_Water_Gardens_1_(4689217353).jpg)

Fort Worth has a total of 263 parks with 179 of those being neighborhood parks. The total acres of parkland is 11,700.72 acres with the average being about 12.13 acres per park.[106]

The 4.3 acre (1.7 hectare) Fort Worth Water Gardens, designed by noted New York architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee, is an urban park containing three pools of water and terraced knolls; the Water Gardens are billed as a "cooling oasis in the concrete jungle" of downtown. Heritage Park Plaza is a Modernist-style park that was designed by Lawrence Halprin.[107] The plaza design incorporates a set of interconnecting rooms constructed of concrete and activated throughout by flowing water walls, channels, and pools and was added to the US National Register of Historic Places on May 10, 2010.[108]

There are two off-leash dog parks located in the city, ZBonz Dog Park and Fort Woof. The park includes an agility course, water fountains, shaded shelters, and waste stations.[109]

.jpg/440px-Texas_Christian_University_June_2017_87_(Amon_G._Carter_Stadium).jpg)

While much of Fort Worth's sports attention is focused on Dallas's professional sports teams,[110] the city has its own athletic identity.

In 2021, it was announced that Austin Bold FC would relocate to Fort Worth, providing Fort Worth with a USL Championship club.[111] Semi-professionally, the Fort Worth Jaguars play in the North American Floorball League and the North Texas Bulls of the National Arena League play at Cowtown Coliseum.[112]

There are three amateur soccer clubs in Fort Worth: Fort Worth Vaqueros FC, Inocentes FC, and Azul City Premier FC; Inocentes and Azul City Premier both play in the United Premier Soccer League.[113] The Vaqueros play in the National Premier Soccer League.[114]

Collegiately, Texas Christian University's athletic teams are the premier college sports teams for Fort Worth. The TCU Horned Frogs compete in NCAA Division I athletics. The Horned Frog football team produced two national championships in the 1930s and remained a strong competitor in the Southwest Conference into the 1960s before beginning a long period of underperformance.[115]

The revival of the TCU football program began under Dennis Franchione with the success of running back LaDainian Tomlinson. Under Gary Patterson, the Horned Frogs have developed into a perennial top-10 contender, and a Rose Bowl winner in 2011.[116] Notable players include Sammy Baugh, Davey O'Brien, Bob Lilly, LaDainian Tomlinson, Jerry Hughes, and Andy Dalton. The Horned Frogs, along with their rivals and fellow non-AQ leaders the Boise State Broncos and University of Utah Utes, were deemed the quintessential "BCS Busters", having appeared in both the Fiesta and Rose bowls. Their "BCS Buster" role ended in 2012 when they joined the Big 12 athletic conference in all sports.

Nearby Texas Wesleyan University competes in the NAIA, and won the 2006 NAIA Div. I Men's Basketball Championship and three-time National Collegiate Table Tennis Association (NCTTA) team championships (2004–2006). Fort Worth is also home to the NCAA football Lockheed Martin Armed Forces Bowl.

There used to be one professional sports team in Fort Worth proper, Panther City Lacrosse Club of the National Lacrosse League. It was founded in 2020 and played at Dickies Arena[117] until it folded in 2024.

Fort Worth hosts an important professional men's golf tournament every May at the Colonial Country Club. The Colonial Invitational Golf Tournament, now officially known as the Fort Worth Invitational, is one of the more prestigious and historical events of the tour calendar. The Colonial Country Club was the home course of golfing legend Ben Hogan, who was from Fort Worth.[118]

Fort Worth is home to Texas Motor Speedway, also known as "The Great American Speedway". Texas Motor Speedway is a 1.5-mile quad-oval track located in the far northern part of the city in Denton County. The speedway opened in 1997, and currently hosts an IndyCar event and six NASCAR events among three major race weekends a year.[119][120]

Amateur sports-car racing in the greater Fort Worth area occurs mostly at two purpose-built tracks: MotorSport Ranch and Eagles Canyon Raceway. Sanctioning bodies include the Porsche Club of America, the National Auto Sports Association, and the Sports Car Club of America.

The annual Cowtown Marathon has been held every last weekend in February since 1978. The two-day activities include two 5Ks, a 10K, the half marathon, marathon, and ultra marathon.[121]

In addition to the weekly rodeos held at Cowtown Coliseum in the Stockyards, the Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo is held within the Will Rogers Memorial Center at the Dickies Arena.[122][123] Dickies Arena also hosts a few TCU basketball games and in the future planned to host college basketball tournaments at the conference and national levels.

.jpg/440px-Fort_Worth_June_2016_16_(City_Hall).jpg)

Fort Worth has a council-manager government, with elections held every two years for a mayor, elected at large, and eight council members, elected by district. The mayor is a voting member of the council and represents the city on ceremonial occasions. The council has the power to adopt municipal ordinances and resolutions, make proclamations, set the city tax rate, approve the city budget, and appoint the city secretary, city attorney, city auditor, municipal court judges, and members of city boards and commissions. The day-to-day operations of city government are overseen by the city manager, who is also appointed by the council.[124] The current mayor is Republican Mattie Parker, making Fort Worth the second-largest city in the United States with a Republican mayor.[125]

The Texas Department of Transportation operates the Fort Worth District Office in Fort Worth.[128]

The North Texas Intermediate Sanction Facility, a privately operated prison facility housing short-term parole violators, was in Fort Worth. It was operated on behalf of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. In 2011, the state of Texas decided not to renew its contract with the facility.[129]

Fort Worth is home to one of the two locations of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. In 1987, construction on this second facility began. In addition to meeting increased production requirements, a western location was seen to serve as a contingency operation in case of emergencies in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area; as well, costs for transporting currency to Federal Reserve banks in San Francisco, Dallas, and Kansas City would be reduced. Currency production began in December 1990 at the Fort Worth facility;[130] the official dedication took place April 26, 1991. Bills produced here have a small "FW" in one corner.

The Eldon B. Mahon United States Courthouse building contains three oil-on-canvas panels on the fourth floor by artist Frank Mechau (commissioned under the Public Works Administration's art program).[131] Mechau's paintings, The Taking of Sam Bass, Two Texas Rangers, and Flags Over Texas were installed in 1940, becoming the only New Deal art commission sponsored in Fort Worth. The courthouse, built in 1933, serves the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2001.[51]

Federal Medical Center, Carswell, a federal prison and health facility for women, is located in the Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth.[132] Carswell houses the federal death row for female inmates.[133] Federal Medical Center, Ft. Worth, a federal prison and health facility for men, is located across from TCC-South Campus. The Federal Aviation Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, and Federal Bureau of Investigation have offices in Fort Worth.

Fort Worth Public Library is the public library system.

Most of Fort Worth is served by the Fort Worth Independent School District.

Other school districts that serve portions of Fort Worth include:[134]

The portion of Fort Worth within the Arlington Independent School District contains a wastewater plant. No residential areas are in this portion.[citation needed]

Pinnacle Academy of the Arts (K–12) is a state charter school, as are Crosstimbers Academy and High Point Academy.

Private schools in Fort Worth include both secular and parochial institutions.

Other institutions:

Fort Worth and Dallas share the same media market. The city's magazine is Fort Worth, Texas Magazine, which publishes information about Fort Worth events, social activity, fashion, dining, and culture.[136]

.jpg/440px-Fort_Worth_June_2016_20_(Star-Telegram_Building).jpg)

Fort Worth has one major daily newspaper, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, founded in 1906 as Fort Worth Star. It dominates the western half of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, and The Dallas Morning News dominates the east.[citation needed] In 2023, the publication's print circulation was 43,342.[137]

The Fort Worth Weekly is an alternative weekly newspaper for the Fort Worth metropolitan division. The newspaper had an approximate circulation of 47,000 in 2015.[138] The Fort Worth Weekly published and features, among many things, news reporting, cultural event guides, movie reviews, and editorials. Additionally, Fort Worth Business Press is a weekly publication that chronicles news in the Fort Worth business community.

The Fort Worth Report is a daily nonprofit news organization covering local government, business, education and arts in Tarrant County.[139] The nonprofit organization, founded by local business leaders and former Fort Worth Star-Telegram publisher Wes Turner,[140] announced its intentions in February 2021 and officially launched the newsroom in April 2021.[141][142]

The Fort Worth Press was a daily newspaper, published weekday afternoons and on Sundays from 1921 until 1975. It was owned by the E. W. Scripps Company and published under the then-prominent Scripps-Howard Lighthouse logo. The paper reportedly last made money in the early 1950s. Scripps Howard stayed with the paper until mid-1975. Circulation had dwindled to fewer than 30,000 daily, just more than 10% of that of the Fort Worth Star Telegram. The name Fort Worth Press was resurrected briefly in a new Fort Worth Press paper operated by then-former publisher Bill McAda and briefer still by William Dean Singleton, then-owner of the weekly Azle (Texas) News, now owner of the Media Central news group. The Fort Worth Press operated from offices and presses at 500 Jones Street in Downtown Fort Worth.[143]

Television stations shared with Dallas include (owned-and-operated stations of their affiliated networks are highlighted in bold) KDFW 4 (Fox), KXAS 5 (NBC), WFAA 8 (ABC), KTVT 11 (CBS), KERA 13 (PBS), KTXA 21 (Independent), KDFI 27 (MNTV), KDAF 33 (CW), and K07AAD-D (HC2 Holdings).

Over 33 radio stations operate in and around Fort Worth, with many different formats.

On the AM dial, like in all other markets, political talk radio is prevalent, with WBAP 820, KLIF 570, KSKY 660, KFJZ 870, KRLD 1080 the conservative talk stations serving Fort Worth and KMNY 1360 the sole progressive talk station serving the city. KFXR 1190 is a news/talk/classic country station. Sports talk can be found on KTCK 1310 ("The Ticket"). WBAP, a 50,000-watt clear-channel station which can be heard over much of the country at night, was a long-successful country music station before converting to its current talk format.

Several religious stations are also on AM in the Dallas/Fort Worth area; KHVN 970 and KGGR 1040 are the local urban gospel stations, KEXB 1440 carries Catholic talk programming from Relevant Radio, and KKGM 1630 has a Southern gospel format.

Fort Worth's Spanish-speaking population is served by many stations on AM:

A few mixed Asian language stations serve Fort Worth:

KLNO is a commercial radio station licensed to Fort Worth. Long-time Fort Worth resident Marcos A. Rodriguez operated Dallas-Fort Worth radio stations KLTY and KESS on 94.1 FM. Four urban-formatted radio stations, KBFB 97.9, KKDA 104.5, KRNB 105.7, and KZMJ 94.5, can also be heard. A wide variety of commercial formats, mostly music, are on the FM dial in Fort Worth.

Noncommercial stations serve the city fairly well. Three college stations can be heard - KTCU 88.7, KCBI 90.9, and KNTU 88.1, with a variety of programming. Also, the local NPR station is KERA 90.1, along with community radio station KNON 89.3. Downtown Fort Worth also hosts the Texas Country radio station KFWR 95.9 The Ranch.

When local radio station KOAI 107.5 FM, now KMVK, dropped its smooth jazz format, fans set up smoothjazz1075.com, an internet radio station, to broadcast smooth jazz for disgruntled fans.

Like most cities that grew quickly after World War II, Fort Worth's main mode of transportation is the automobile, but bus transportation via Trinity Metro is available, as well as an interurban train service to Dallas via the Trinity Railway Express. As of January 10, 2019, train service from Downtown Fort Worth to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport's Terminal B is available via Trinity Metro's TEXRail service.

The first streetcar company in Fort Worth was the Fort Worth Street Railway Company. Its first line began operating in December 1876, and traveled from the courthouse down Main Street to the T&P Depot.[144] By 1890, more than 20 private companies were operating streetcar lines in Fort Worth. The Fort Worth Street Railway Company bought out many of its competitors, and was eventually itself bought out by the Bishop & Sherwin Syndicate in 1901.[145] The new ownership changed the company's name to the Northern Texas Traction Company, which operated 84 miles of streetcar railways in 1925, and their lines connected downtown Fort Worth to TCU, the Near Southside, Arlington Heights, Lake Como, and the Stockyards.

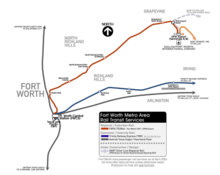

At its peak, the electric interurban industry in Texas consisted of almost 500 miles of track, making Texas the second in interurban mileage in all states west of the Mississippi River. Electric interurban railways were prominent in the early 1900s, peaking in the 1910s and fading until all electric interurban railways were abandoned by 1948. Close to three-fourths of the mileage was in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, running between Fort Worth and Dallas and to other area cities including Cleburne, Denison, Corsicana, and Waco. The line depicted in the associated image was the second to be constructed in Texas and ran 35 miles between Fort Worth and Dallas. Northern Texas Traction Company built the railway, which was operational from 1902 to 1934.[146]

In 2009, 80.6% of Fort Worth (city) commuters drive to work alone. The 2009 mode share for Fort Worth (city) commuters are 11.7% for carpooling, 1.5% for transit, 1.2% for walking, and .1% for cycling.[147] In 2015, the American Community Survey estimated modal shares for Fort Worth (city) commuters of 82% for driving alone, 12% for carpooling, .8% for riding transit, 1.8% for walking, and .3% for cycling.[148] The city of Fort Worth has a lower than average percentage of households without a car. In 2015, 6.1 percent of Fort Worth households lacked a car, and decreased to 4.8 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Fort Worth averaged 1.83 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[149]

Fort Worth is served by four interstates and three U.S. highways. It also contains a number of arterial streets in a grid formation.

Interstate highways 30, 20, 35W, and 820 all pass through the city limits.

Interstate 820 is a loop of Interstate 20 and serves as a beltway for the city. Interstate 30 and Interstate 20 connect Fort Worth to Arlington, Grand Prairie, and Dallas. Interstate 35W connects Fort Worth with Hillsboro to the south and the cities of Denton and Gainesville to the north.

U.S. Route 287 runs southeast through the city connecting Wichita Falls to the north and Mansfield to the south. U.S. Route 377 runs south through the northern suburbs of Haltom City and Keller through the central business district. U.S. Route 81 shares a concurrency with highway 287 on the portion northwest of I-35W.

Notable state highways:

.jpg/440px-Fort_Worth_June_2016_07_(Fort_Worth_Transportation_Authority).jpg)

Trinity Metro, formerly known as the Fort Worth Transportation Authority, serves Fort Worth with dozens of different bus routes throughout the city, including a downtown bus circulator known as Molly the Trolley. In addition to Fort Worth, Trinity Metro operates buses in the suburbs of Blue Mound, Forest Hill, River Oaks and Sansom Park.[150]

In 2010, Fort Worth won a $25 million Federal Urban Circulator grant to build a streetcar system.[151] In December 2010, though, the city council forfeited the grant by voting to end the streetcar study.[152]

In July 2019, Trinity Metro partnered with Via Transportation to launch an on-demand microtransit service called ZIPZONE. ZIPZONE offers shared rides across the Alliance, Mercantile, Southside, and South Tarrant neighborhoods and was designed as a first-and-last mile connection for TEXRail and bus commuters.[153][154][155] Trips are booked from a smartphone app and charge a flat $3 for service as of April 2021. ZIPZONE rides are also included with multi-ride Trinity Metro local tickets.[156]

Dallas Fort Worth International Airport is a major commercial airport located between the major cities of Fort Worth and Dallas. DFW Airport is the world's third-busiest airport based on operations and tenth-busiest airport based on passengers.[158]

Prior to the construction of the DFW Airport, the city was served by Greater Southwest International Airport, which was located just to the south of the new airport. Originally named Amon Carter Field after the publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Greater Southwest opened in 1953 and operated as the primary airport for Fort Worth until 1974. It was then abandoned until the terminal was torn down in 1980. The site of the former airport is now a mixed-use development straddled by Texas State Highway 183 and 360. One small section of runway remains north of Highway 183, and serves as the only reminder that a major commercial airport once occupied the site.

Fort Worth is home to these four airports within city limits:

A 2011 study by Walk Score ranked Fort Worth 47th-most walkable of 50 largest U.S. cities.[159]

Fort Worth is a part of the Sister Cities International program and maintains cultural and economic exchange programs with its sister cities:[160]

Today the Catholic Diocese of Fort Worth has grown from 60,000 Catholics in 1969 to 1,200,000 Catholics. The Diocese comprises 92 Parishes and 17 Schools, with 132 Priests (67 are Diocesan), 106 Permanent Deacons and 48 Sisters.